| THE BACKSTORY ON WISCONSIN'S FAVORITE BADGER

| THE BACKSTORY ON WISCONSIN'S FAVORITE BADGER

Like

Communications Director Katie L. Grant

Publications Supervisor Dana Fulton Porter

Publications Supervisor Andi Sedlacek

Managing Editor Andrea Zani

Associate Editor Kathryn A. Kahler

Art Direction Bailey Nehls

Printing Schumann Printers

Wisconsin Natural Resources magazine (USPS #34625000) is published quarterly in Spring, Summer, Fall and Winter by the Wisconsin Depart ment of Natural Resources. The magazine is sustained through paid subscriptions. No tax money is used. Preferred Periodicals postage paid at Madison, WI. POSTMASTER and readers: Subscription questions and address changes should be sent to Wisconsin Natural Resources, P.O. Box 37832, Boone, IA 50037-0832. Subscription rates are: $8.97 for one year, $15.97 for two years and $21.97 for three years. Toll-free subscription inquiries will be answered at 1-800-678-9472.

© Copyright 2023, Wisconsin Natural Resources magazine, Wisconsin Depart ment of Natural Resources, P.O. Box 7191, Madison, WI 53707; wnrmag.com

Contributions are welcome, but the Wis consin Department of Natural Resources assumes no responsibility for loss or damage to unsolicited manuscripts or illustrative material. Viewpoints of authors do not necessarily represent the opinion or policies of the State of Wisconsin, the Natural Resources Board or the Department of Natural Resources.

Printed in Wisconsin on recycled paper using soy-based inks in the interest of our readers and our philosophy to foster stronger recycling markets in Wisconsin.

Governor Tony Evers

Natural Resources Board

Bill Smith, Shell Lake, Chair

Sharon Adams, Milwaukee

Paul Buhr, Viroqua

Dylan Bizhikiins Jennings, Odanah

Sandra Dee E. Naas, Ashland

Jim VandenBrook, Mount Horeb

Marcy West, La Farge

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources

Adam N. Payne, Secretary

Steven Little, Deputy Secretary

Mark Aquino, Assistant Deputy Secretary

23 14 trails to fall for

26 Back to Belmont

28 All about Bucky

32 Deer hunting past, present and future

36 Breaking down deer season

38 Wellness check

40 Falling for apples

44 Fun with all that falls

have been with my dad, son and daughters by my side.

Like so many of you, I cherish our hunting opportunities and spending time with family and friends. Whether you’re a seasoned hunter or a novice eager to get in the woods, you’ll find every Wisconsin hunt has promise to be a unique adventure that will leave lasting memories.

Often, these hunts are in or near forests. These woodlands serve as more than just a scenic landscape; our forests hold a pivotal role in Wisconsin’s history and have helped shape the state we know today. From the towering pines of the Northwoods to the sweet maple trees we tap for syrup, Wisconsin’s forests have been both economic engines and ecological wonders for centuries.

Working with so many talented and passionate people at the DNR is a privilege. Our staff are dedicated to protecting and enhancing Wisconsin’s natural resources, and I’m grateful to Gov. Evers and the Legislature for passing the 2024-2025 budget and showing their support for our staff and the work the agency does.

The two-year budget provided the department with an overall 7.5% increase that will help us respond more effectively to water pollution, including PFAS, nitrates, phosphorus and lead, and better positions us to help people and communities in need. There are also key investments in our state park system. I am grateful for the investments in public safety, including safety equipment for our conservation wardens and firefighters, which will help us recruit and retain staff.

So much of the DNR’s diverse work

is highlighted during the fall. The crisp autumn air signals the start of my favorite season in the Badger State filled with spectacular fall colors, picking apples and harvesting crops, and the excitement and anticipation of spending more time in the woods.

Our hunting culture runs deep in Wisconsin, where traditions intertwine with a profound respect for nature. Many hunters flock to Wisconsin for our top-tier deer hunting, but as many of you know, we have a wide range of game to pursue and habitats to explore.

Personally, several years have passed since I went grouse or duck hunting, but I hope to change that soon with my son, Forrest. Please be sure to involve your kids and grandkids or invite a first-time hunter to join you when you head out in the field this year. It may take a little extra time or patience, but my best hunts

Through sustainable forest and wildlife management, the DNR is committed to continuing our legacy. Now that I am a grandpa, I feel even stronger about the department’s mission to help assure our air, land and water are healthy and protected for generations to come.

Within these pages, you’ll find more information on both hunting and forestry, their histories and what the next chapters may hold. Additionally, enjoy a highlight of some of the best trails for autumnal views, an apple cake recipe to savor and the story of the most beloved badger in Wisconsin, Bucky.

Whether you find yourself reading this in front of the wood stove, a campfire, or gearing up for a Saturday Badger football game, I hope you have a wonderful fall season and take a moment to celebrate and be grateful for all the things that are firmly rooted in our state.

On, Wisconsin!

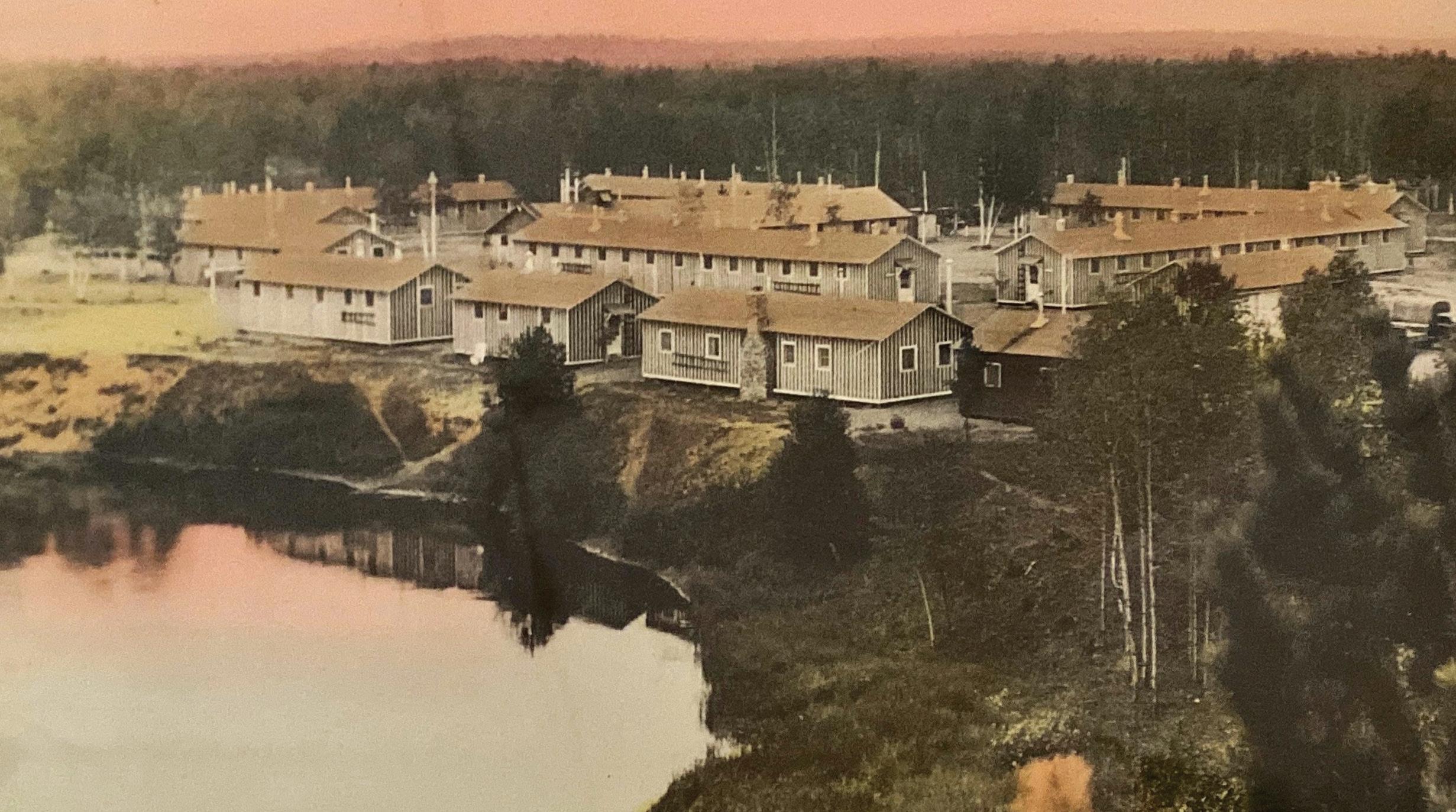

Take time this fall to experience the newest hiking trail at the Northern Highland-American Legion State Forest — the Camp Mercer Interpretive Trail. Winding along the Manitowish River, the mostly flat 3-mile trail explores the sites of two old logging camps and a former Civilian Conservation Corps camp.

About two dozen interpretive signs along the way detail the area’s rich history. Visitors should remember to observe but not disturb mound areas and other cultural elements of the trail.

The Camp Mercer Interpretive Trail is the work of the DNR and many partners. Find the trailhead on the Manitowish River access road off State Highway 51, about a mile west of the Vilas County-Iron County line.

Scan the QR code for information, including trail maps and more about the CCC camp, or check dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1761.

DNR wardens Erik Anderson and Mike Neal were presented with the Protect & Serve Award for their outstanding public service, honored at a May 15 ceremony at Lambeau Field in Green Bay. The event was part of the Green Bay Packers Give Back community outreach program.

The two DNR wardens were among 17 Wisconsin law enforcement officers, departments and a K9 honored for their exemplary dedication by going above and beyond the call of duty. Packers President and CEO Mark Murphy and Pro Football Hall of Fame inductee LeRoy Butler were among the guest speakers and presented the awards — hand-crafted American flag plaques made by Oneida Police Sgt. Nathan Ness.

Each award recipient also named a department or nonprofit to which the National Football League Foundation issued a $2,000 grant. Anderson selected the Hmong American Friendship Association, and Neal selected the Door County Dive Team and the Gibraltar Fire and Rescue Association.

Stay in the loop on Wisconsin’s fall color show with the Department of Tourism’s Fall Color Report. Check the latest color status by county, plan trips and sign up for email updates at travelwisconsin.com/fall-color-report.

You can now get free one-day state park admission passes at dozens of public libraries statewide. “Check Out Wisconsin State Parks at Your Library,” a collaboration of the DNR, libraries and program sponsors, offers free one-day park passes at more than 160 libraries around the state. The passes are valid for single-day vehicle admission at any state park, forest or recreation area where an admission pass is required.

For a county-by-county list of participating libraries, scan the QR code or check dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1751.

We saw this on one of our hanging flowers. It was larger than a bumble bee but half the size of a hummingbird. It flew like a hummingbird and had a beak like one. Some sort of a moth? We’ve never seen something like that before.

Doug and Karen Kurschner Turtle LakeInteresting creature! You are right on track when you mention hummingbird and moth because its ID includes both: It is a hummingbird moth, of the genus Hemaris

According to UW Extension’s Wisconsin Horticulture Division, hummingbird moths like to dart from flower to flower, using a long proboscis to extract nectar. When not in use, the proboscis coils up just like a party noisemaker!

I love your magazine and pictures. I have a home in the Harrison Hills (Lincoln County). This past fall, I found the colors extremely vibrant compared to other years. I have Parkinson's, and taking pictures is easy to do with the beauty of the Harrison Hills! Exercise is key to slow this disease, and I can't think of a better way than to drive and hike this beautiful area of Wisconsin.

Daniel Weslo Medinah, IllinoisKatie Grant’s “Deer Butchering Tips” in the Summer edition was a great article. I shot my first buck when I was about 16. It was on Thanksgiving Day. I was told to meet at a location at 6 p.m., at an address in Sauk City, on a Monday evening to help butcher it.

My dad was a farmer who’d butchered our family animals, but he died when I was 10. That Monday, I received great training. I’m now 74 and have since killed more than 100 deer, one bear, lots of squirrels, grouse, turkeys, pheasants, rabbits — and still haven't paid even $1 to have anything butchered.

Her information was great. Thanks for letting the younger generation know!

Vern Denzer HolcombeThis year, my husband and I have counted six leucistic deer in the Oconomowoc area! I just want to share this photo — the big guy.

Kathleen Janik Oconomowoc

Kathleen Janik Oconomowoc

Why do you refer to the sharptailed grouse as a game bird when, according to the article “Fighting for “Firebirds“ (Summer 2023), there are only 164 males found in Wisconsin? Is there really a hunting season for these birds? When is a rare bird no longer a game bird? I’m not antihunting, just curious.

Karen Ecklund MadisonThanks for the letter, Karen, and you pose interesting questions. Although sharp-tailed grouse populations have been declining, the DNR and partners are hopeful the bird will respond positively to ongoing significant habitat management efforts, notably in northwest Wisconsin, where important barrens habitat remains.

The DNR also is in the process of developing a new statewide management plan, with efforts informed by the Sharp-tailed Grouse Advisory Committee, a diverse group including government agencies, tribal interests, conservation groups and non-governmental organizations. Each year, the committee uses spring dancing ground surveys to determine if a sharp-tailed grouse hunting season is appropriate and at what levels. No permits will be issued this year, but by state law the bird will retain its status as a game species.

You asked, our DNR experts answered. Here's a quick roundup of some frequently asked questions we've received.

Q: Am I allowed to harvest a buck with a bow during the statewide antlerless hunt?

A: Although the archery seasons remain open through the firearm seasons, harvest is restricted to antlerless deer for all weapon types during any antlerless firearm season. This makes it very clear that bucks are not being taken illegally with firearms and registered under an archery license. High-visibility clothing rules also apply during these hunts. These rules apply statewide during the four-day antlerless hunt in early December and in any Farmland Zone Deer Management Unit that has the antlerless-only holiday hunt.

Q: I'm thinking ahead for holiday gifts, and I want to get some annual state park vehicle admission stickers for my friends and family. When will they go on sale?

A: The 2024 state park and forest vehicle admission stickers will be available to purchase on Nov. 24. You can buy them at state park and forest properties, at DNR service centers and online at yourpassnow.com/parkpass/wi.

Q: I'm planning to take someone hunting for the first time, and they use a wheelchair. Are there any hunting blinds we can use around the state?

A: First, thank you for introducing a new hunter to this great Wisconsin tradition! Second, yes, there are 20 public lands around the state with hunting blinds that provide a stable platform for hunters looking for accessible hunting opportunities for deer, turkey and waterfowl hunting. These hunting blinds also generally have wide entryways and ramps, making it easier to enter and move around for the perfect view.

Check out our list of hunting blinds on DNR public lands and state park properties at dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1766. Contact the property directly before heading there to hunt to ensure the blind is open and available.

One more thing: Did you know Wisconsin has a gun deer hunting season for hunters with disabilities? It’s held every October (Oct. 7-15 this year), and to be eligible, hunters must possess a valid Class A, C, D, or long-term Class B permit with privileges to shoot from a stationary vehicle. Hunters with one of those permits should contact a sponsoring landowner before Sept. 15 to participate. Learn more about deer hunting for hunters with disabilities at dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1851.

Q: As the weather gets colder, I've seen a few snakes lying on the road in the sun. Why are they doing this?

A: As the days and nights get cooler, our cold-blooded reptile friends turn to warm asphalt to soak in one last bit of warmth for the day. This makes them particularly vulnerable to being run over by vehicles, but you can help us and them!

We're working to identify where these live sightings or road mortalities occur most often to help reduce this threat and better understand where these species exist in the state. Help out your neighborly snakes, frogs, salamanders and more by reporting live or dead reptile and amphibian observations to the Reptile and Amphibian Road Mortality Form: dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1771.

Although Wisconsin is proudly known as the Dairy State, another thriving industry deserves recognition — timber.

Forestry has deep roots here, shaping the history and contributing significantly to Wisconsin’s economic development for generations.

Long before European settlers arrived, Native Americans actively managed the forested land that would eventually become Wisconsin. Contrary to the misconception of a hands-off approach, they viewed these forests as a vital part of their lives.

When the settlers arrived, Wisconsin’s forests became instrumental in building cities throughout the Midwest. Timber was harvested and shipped all over, from Chicago to Indianapolis to Des Moines.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, Wisconsin’s dense forests attracted pioneers and loggers hoping to harness the vast timber resources. Lumber mills and logging camps dotted the landscape, shaping communities and driving progress.

The timber industry played a crucial role in building the state’s infrastructure, providing the raw materials for con-

struction and fueling the expansion of railroads.

As the decades rolled on and the industry evolved, Wisconsin became renowned for sustainable forest practices. Forest conservation and responsible timber harvesting continue to be at the forefront for the DNR, setting us up as a national leader.

Today, the timber industry is a significant sector of the state’s economy, injecting $24 billion annually into the state. It is the No. 1 employer in several counties.

Forestry supports numerous jobs, both directly and indirectly, and provides renewable, environmentally friendly sources of construction materials. The industry continues to embrace technological advancements, including the utilization of mass timber, further positioning Wisconsin as a leader in the green construction sector.

Timber’s legacy and forward momentum reflect a deep respect for responsible land practices and resource management, showcasing how Wisconsin’s roots contribute to a sustainable future.

Dana Fulton Porter is a publications supervisor in the DNR’s Office of Communications.Downtown Milwaukee may feel like the last place you’d notice the forest industry. But it’s here you’ll find Ascent MKE, a 25-story high-rise featuring luxury apartments, retail space and a sky deck.

This building stands out in the sea of other Milwaukee high-rises; at the time of this writing, Ascent MKE is the world’s tallest mass timber structure, edging out Norway’s Mjøstårnet.

It's an engineering feat and a look at the future of both sustainable construction and a thriving forest products industry.

Historically, timber has been the skeleton in structures up to about five stories tall, yielding then to steel and concrete for taller buildings.

Progressive architecture coupled with a better understanding of the carbon footprint of traditional materials is now leading to a new era for wood-based construction.

Mass timber refers to a suite of engineered wood prod-

ucts that includes cross-laminated timber, glue-laminated timber and dowel-laminated timber. These materials are created by layering and bonding multiple pieces of wood together, forming panels and beams as strong and stable as concrete, steel or heavy timber.

“Cross-laminated timber is the most common. It is basically lumber that is orientated 90 degrees to each other, glued and stacked almost like Jenga blocks,” said Collin Buntrock, former DNR Forest Products team leader. “This technique allows architects and builders to use wood to build tall buildings.”

Mass timber buildings are aesthetically pleasing and structurally sound, passing seismic activity tests and fire stress better than concrete or steel.

“As the wood is exposed to flame, it has a predictable rate of failure,” Buntrock said. “You’d think steel would hold up to fire better, but it actually fails more severely and is unpredictable. Every type of steel is a little bit different.”

In the last decade, the number of mass timber projects in the U.S. has increased almost 60-fold. They still represent only a small percentage of the annual construction in the U.S., but the trend line is growing, as is the average size of such projects.

For this momentum to continue, building codes and certain regulations will likely need to evolve and be updated. Variance processes exist to help with dated building codes, but it is an additional step.

“New codes will allow for newer, taller buildings to be built without going through that process,” Buntrock noted.

The benefits are twofold — new mass timber structures add economic value to communities while simultaneously sequestering carbon for decades.

The influence of forest products resonates far beyond architecture.

“We can’t get up in the morning without encountering a forest product that we can produce sustainably,” Buntrock said.

Ice cream, macaroni and cheese, biochemicals, toothpaste thickener and biodegradable computer chips all have wood derivatives that help make them the products we know and love. The popularity of sustainable packaging, such as boxed water, holds huge opportunities for Wisconsin’s forests.

Wisconsin also is leading the charge on using innovative products, such as the microscopic bits of tree cells known as nanocellulose, to bring forest products into more industries.

These products, no matter how small, each play a role in climate mitigation.

“All wood products are carbon storage modules,” Buntrock said. That includes everything from solid wood products to the micro and nanoscale.

Additionally, according to the USDA Forest Service, wood products have lower embodied carbon, the amount of carbon required to reach the market, compared to steel or concrete.

Economic gains, cultural significance and ecological stability — Wisconsin’s forests and the wood products industry are important for each area. Buntrock compared it to a three-legged stool, each as important as the other.

Thanks to ongoing innovation and a commitment to sustainability, Wisconsin’s trees are no longer merely rooted in the forest floors of northern Wisconsin and are making an impact every day across the country.

For more about forest products research, check the website for the USDA Forest Service’s Forest Products Lab: fpl.fs.usda.gov.

Wisconsin’s Northwoods is remarkable, a beloved region known for stunning views of mixed hardwood and coniferous forest.

While many Midwesterners only think of the forest as an area covering Wisconsin, Michigan and Minnesota, our “Northwoods” is actually the southern fringe of a much larger forest stretching across the northern United States and southern Canada.

Animals large and small — from moose to otters to grouse — call the region home. It also serves as a crucial migration corridor, providing stopover sites and interconnected habitat for breeding, nesting and feeding for many long-distance migratory birds.

Driving north from southern Wisconsin, you’ll travel through warmer grasslands and oaks, a “tension zone,” or climate boundary of sorts. As you arrive in the colder Northwoods, you’ll find a landscape dominated by hardwoods and conifers.

Even the smallest changes in our climate are visible on this frontier. The forest is a stage for climate change concerns like more frequent pest outbreaks — such as spongy moth, which favor dry, hot weather — or the slow and steady creep of more southern trees and wildlife into northern Wisconsin, matching the withdrawal of paper birch and spruce grouse.

While this climate adaptation plays out in our backyard, the Northwoods region also plays a key role in climate change mitigation. The vast intact forests act as a carbon sink, absorbing significant amounts of carbon dioxide, keeping it out of the atmosphere and storing the carbon in the soil, trees and future forest products.

Recognizing the ecological importance of the Northwoods and its connection to our communities, the DNR is committed to sound forest management, through methods like reforestation and sustainable logging, and will continue to protect and manage Wisconsin’s portion of the great Northwoods.

Whatever your reason for planting a tree — shade, energy efficiency or to do your part for the environment — fall is a great time to give it a go.

Brian Wahl, urban forestry specialist for the DNR, says fall’s cooler air temperatures coupled with soil warmed over summer promote root growth essential for establishing healthy trees.

“Anytime from when the weather turns cool until the ground starts to freeze is fine,” Wahl said. “But prime tree-planting time is September and October.”

Evergreens should be planted earlier rather than later to give them more time to establish roots before winter, he noted.

Aside from timing, two things are key to planting trees in fall — planting at the right depth and ensuring adequate moisture.

“’Bare the flare’ is the tagline I use to help folks find the right depth,” Wahl said. “We want to see the root flare — where the trunk meets the roots — at the soil surface. Trunk tissue isn’t meant to be underground.”

Baring the flare also helps prevent root girdling, when roots encircle the trunk, eventually strangling the tree.

Follow these 10 steps for a healthy tree and a lifelong investment.

1. Call Diggers Hotline at 1-800-242-8511 or go to diggershotline.com to have underground utilities marked.

2. Choose a spot with enough space for your tree to grow into over the years. Plant trees no closer than 4-5 feet from any utility lines.

3. Determine where the root flare is located within the root ball. Measure the width and height of the root ball, from root flare to bottom.

“Planting a Tree from a Container,” a YouTube video, walks through the process — scan the QR code or check dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1731.

For forest landowners, the DNR has a wealth of information regarding larger-scale reforestation projects, including planning and design tips, reforestation supply resources and how to order seedlings beginning in October for spring 2024 planting — dnr.wi.gov/topic/treeplanting.

4. Dig a hole no deeper than the height of the root ball but at least twice the width. Use a trowel to break up compacted dirt around the edge of the hole.

5. Remove all tags and packaging from the tree, including twine, wire and burlap, and carefully set or roll the tree into the hole.

6. Carefully remove soil from the top of the root ball to bare the flare. Be sure the root flare is at or slightly above ground level.

7. Backfill the hole with the excavated soil, breaking up large clumps and watering as you go.

8. Water thoroughly with 5 to 10 gallons of water for every inch of trunk diameter.

9. Cover the dirt around the tree with 2 to 4 inches of mulch, keeping it away from the trunk.

10. Enjoy your tree and make it count! Record it on the DNR’s Wisconsin Tree Planting Map so it counts toward Gov. Tony Evers’ state tree-planting pledge as part of the Trillion Trees Initiative — dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1721.

The sound of birds chirping and chimes clanging. The fragrant smell of chives and mint leaves. The feel of rough walnut husks and pinecones. The sight of a brightly colored butterfly flitting through the air.

These sensations and more contribute to the multi-sensory experience at the Nature Explore Classroom at Richard Bong State Recreation Area in Racine County. The space is a godsend for a Wisconsin mom of three, Rikki Cartwright.

“My 4-year-old son is on the autism spectrum, and we visit the Nature Explore Classroom with his therapist on a weekly basis, year-round, to work on life skills,” said Cartwright, of nearby Rochester.

The classroom is a safe place for her kids, ages 4, 5 and 6, to explore, practice problem-solving and be creative, things they sometimes struggle with in a traditional classroom setting.

“When you're indoors with lots of people in close proximity, all that stimulation creates lots of noise, anxiety and stress,” Cartwright said. “The outdoor classroom gives my son space and privacy to explore and learn things on his own terms.”

Established in 2019, the 1-acre classroom is the first of its kind in Wisconsin state parks.

The premise is simple: Make the outdoors more accessible for all ages and abilities. The classroom is comprised of 11 stations, all thoughtfully designed by a research-based Nebraska company called Nature Explore, including:

• Music and movement station to make sounds from chimes, drums and a PVC-pipe organ.

• Two art stations, where you can use natural materials to create your next work of art.

• Climbing station, to hop across wooden logs or crawl your way across a log bridge.

• Areas to build, weave, dig in the dirt and sand, and play in water. The classroom’s many structures and architectural features are made from materials sourced right from the recreation area itself. All play spaces and the intertwining gravel paths connecting them are ADA-compliant and wheelchair accessible.

As a DNR naturalist at Bong, Beth Goeppinger spearheaded the project before retiring in 2021. Her goal was for the Nature Explore Classroom to help visitors, especially kids, connect with the outdoors.

“I worked for the DNR for 28 years, and I've seen how things have changed with kids and the disconnect from nature as they spend more time indoors, often on screens,” Goeppinger said. “I thought this was a perfect way to bring the kids back outside and reengage with nature by allowing them to explore on their own.”

For Cartwright, each of her kids has a different favorite element of the park. Her older daughter heads straight to the jungle gym area to get climbing, while her younger daughter seeks out the music station each visit. Her son, youngest of the three, likes to alternate between the sand, water and building areas.

“When you visit — and we do a lot — it's a new experience every time,” she said. “It's just a great place to go.”

Creating the classroom was no small feat. It took over 10 years of planning and designing and thousands of dollars in fundraising, as well as dedicated work, in-kind labor and materials from multiple local construction companies and volunteers to make it a reality.

The Bong Naturalist Association was closely involved, as well as the Arbor Day Foundation, local Boy Scout chapters, the DNR’s accessibility coordinator and other DNR staff. Today, it is dutifully maintained by volunteers.

Goeppinger hopes Bong’s classroom will serve as an example to other organizations striving to make the outdoors more accessible for all.

“Studies have shown over and over and over how calming and soothing and restorative nature is for people,” Goeppinger said. “And no one should be excluded from that.”

Molly Meister is a public information officer in the DNR’s Office of Communications.

Scan the QR code for more about Richard Bong State Recreation Area and the Nature Explore Classroom or visit dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1756. If you’re interested in volunteering or making a financial contribution to maintain the site, contact the Bong Naturalist Association at bongnaturalistassociation.org.

For over a decade, “Old Bat” — as she’s lovingly but perhaps not creatively monikered — has flown from her hibernation site without fail every year to end up at the same roost in Wisconsin.

Since Old Bat was tagged in 2011, the team of conservation biologists and mammal ecologists at the DNR who study bats have found her over and over in the same summer home. This little brown bat native to the state is one of the survivors of white-nose syndrome, a devastating fungal disease.

White-nose syndrome arrived in the state around 2014 and wiped out much of Wisconsin's hibernating bat population. Up to 90% of Wisconsin’s native species of hibernating bats — the little brown bat, big brown bat, tricolored bat (formerly the eastern pipistrelle) and northern long-eared bat — have disappeared.

But not all bats succumbed to the disease, and now, nearly a decade later, the scientists who study them are keen to know why. With some species like the northern long-eared bat being listed as federally endangered, the team is hopeful that solving this mystery will be key in helping other bats to survive as well.

When doing hibernation surveys in winter, biologists mark and weigh rare species like this tricolored bat.

Before banding or tagging, captured bats are assessed for species, age, reproductive condition and anything of note such as scarring on wings from white-nose syndrome.

As white-nose syndrome swept through the state and bat populations plummeted, scientists initially thought to eradicate the disease. Ten years later, it is endemic, a constant presence in bat communities.

The focus has now shifted, according to Jennifer Redell, DNR conservation biologist and cave and mine specialist.

“At this point, we’re really interested in why bats are coexisting with the fungus,” she said. “The bats made it through that initial wave of the disease invasion, and we want to find out why that is.”

To do this, the team has implemented a few tactics, including Passive Integration Transponder tagging, which allows them much more insight into bat behavior.

Despite being very long-lived, bats are tiny mammals; they can’t fly with a GPS collar weighing them down. Traditional banding of bats is time-consuming and difficult. PIT tags, on the other hand, are easier to monitor.

PIT tags are tiny microchips, the same size and kind used for domestic cats and dogs, that ping when they pass specific antennae set up to capture bat movement. While PIT tagging is not new technology nor unique to the state, Wisconsin has expanded on it to have antennae at both summer and winter sites to record movement between the two habitats.

“It’s special to Wisconsin,” Redell said. “It’s just the tip of the iceberg. We’re going to learn a lot more going forward.”

One reason this work is so important is because it gives information on bat behaviors and habitats. In other words, if researchers know where bats are and what they’re doing, the DNR can do a better job of protecting them.

“We want to support the persisting colonies and understand how we can help,” said J. Paul White, mammal ecologist and team lead for the DNR bat program.

Before PIT tagging, there were few connections state scientists could see of bat travel from a summer site to a winter site. Since PIT tagging, the team has gathered multiple data points indicating bats make trips from summer roost to winter hibernating spots several times between May and August before settling in to hibernate for the winter.

Researchers have hypothesized that mother bats may be teaching their pups how to find locations to hibernate, White said.

“Now, we’re looking to see if this tells us what times of year they might be more vulnerable and how we can help them survive these long journeys back and forth,” he said.

Bats — on top of being adorable, furry, flying machines — are critical parts of the ecosystem and the economy.

“Studies have shown that bats can eat 1,000 mosquito-sized insects every hour,” Redell said.

The U.S. Geological Survey notes that considering only the sheer number of insects bats consume, they save agriculture anywhere from $3.7 billion to $53 billion a year on pest-control measures.

Big brown bats often form large clusters when hibernating.

PIT tag readers at hibernation sites record tagged bats that fly past, allowing biologists to monitor movement year-round.

JENNIFER REDELL PHOTOS

JENNIFER REDELL PHOTOS

Despite these incredible financial numbers, Redell said, “bats traditionally have been misunderstood, underfunded and understudied,” though the arrival of white-nose syndrome has improved this somewhat. Biologists across the state and nation are working together to learn more about bats to support conservation.

Some of this work is already being seen in timber management. Heather Kaarakka, a DNR conservation biologist, is leading the work on habitat conservation for forest bats.

The hibernating bat species use trees for foraging and roosting, as well as for giving birth. Before pups can fly on their own, Kaarakka said, mothers often will leave to find food, leaving the pups in those roosts.

“We’ve done work that shows they’ll move around and need multiple roosts during the summer,” she said.

The forests play a critical role for the bats, and poorly timed timber harvest could harm them or take away much-needed habitat.

To ensure forest bats in the Great Lakes region have safe access to the trees they need, the Wisconsin, Mich-

igan and Minnesota DNRs are collaborating to devise a conservation plan that responsibly manages timber cutting to protect forest-dwelling bats like the northern long-eared.

Recently listed as federally endangered, the northern long-eared bat has all but disappeared from Wisconsin. While researchers once found many northern long-eared bats, they now have sites where they may find only a single bat.

Finding just one bat where there used to be many might seem depressing, but it’s meaningful.

“People forget that even zero is a number. It’s important data,” White said.

He underscored the critical role community members played when white-nose syndrome first blindsided the nation in the early 2000s. Through community monitoring programs, Wisconsin residents collect data like the acoustic sounds of bats that are using echolocation, the way bats navigate by bouncing sound off objects and insect prey.

Over the years, this has helped the DNR determine how many bats are still flying the night skies.

“You can’t say enough about how much the volunteers shaped how we understand bats,” White said. “If not for them, we wouldn’t have the information we have today.

“They’ve done a great job of surveying our high-priority sites. We’re very thankful.”

Along with PIT tagging and traditional counting in winter sites, ongoing monitoring programs show there may be some good news on the horizon.

Little brown bat populations have stabilized, and some seem to be climbing back. Wisconsin is home to a significant hibernating site that saw a 17% population increase since it bottomed out a few years ago, Redell said. About 37% of the number of bats once found at that site exist now.

Through conservation programs and collaboration with other state and national departments, it may be possible to see bat populations continue to grow. But the team is cautious in its optimism, understanding that, at such low numbers, bat species remain vulnerable to other unforeseen diseases or habitat changes.

Still, that doesn’t stop them from smiling every time Old Bat or one of their other decades-old veterans returns to their summer roost.

It’s a gratifying feeling, White said: “It’s tough not to get excited about a bat who went through the whitenose syndrome disease cycle and came out on the other end.”

Anna Marie Zorn has background as a science writer and is communications manager for the National Wildlife Federation’s Great Lakes Regional Center.

Bats are vital to many ecosystems, but the effects of white-nose syndrome have been disastrous for populations in Wisconsin and nationwide. The DNR is working hard to support these important species, and there are many ways you can help:

• Join a community science monitoring program to be more inclusive.

• Report sick and dead bats.

• Correctly build and place bat houses.

• Garden organically with fewer pesticides.

• Plant night-blooming flowers to attract insects. The Wisconsin Bat Program offers details on how to get involved on behalf of bats — wiatri.net/inventory/bats. And the Winter 2021 issue of Wisconsin Natural Resources includes detailed instructions for “How to Build a Bat House” — dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1776.

For general bat information and additional bat resources, scan the QR code or check dnr.wi.gov/tiny/886.

This late 1800s or early 1900s photo shows one of two long piers then active in Centerville, also called Hika, in Manitowoc County and now part of the village of Cleveland. The visible older pilings indicate evidence of rebuilding over time.

Imagine, if you will, a thriving shipping town. Dock workers haul cord after cord of wood onto huge schooners destined for Chicago. On shore, goods of all sorts are bought and sold at the general store. Families flock to the area to find work and build lives.

Now, imagine that in just a generation or two, it vanishes. It’s as if this place never even existed.

Sound like the premise of a maritime-themed episode of “The Twilight Zone”? It’s not — the story is real. And it happened up and down Wisconsin’s Lake Michigan coast.

These are Wisconsin’s “ghost ports.”

Like many communities, these port towns developed around economic opportunity. In this case, it was the lumber boom of the mid-1800s.

As the nation grew rapidly, so did the demand for lumber for construction, as a fuel source for boats and a heat source for homes. The rush began to get lumber to the shore of Lake Michigan and onto one of the large commercial vessels headed to the lumber yards in Chicago. Ports made that possible, and consequently, they quickly began to dot the Lake Michigan shoreline.

Some of the first ports to appear still stand today —

Manitowoc, Sheboygan, Kewaunee, Port Washington, Algoma — places that were able to adapt and survive when fortunes eventually changed.

“The big ports, the ones that we still see today, were located on the big rivers in the area,” said Amy Rosebrough, staff archaeologist with the Office of the State Archaeologist at the Wisconsin Historical Society.

“Those ports received government funding and access to larger rivers where they could move and store timber,” she added.

While the main rivers quickly filled with larger ports, smaller ports also developed as enterprising individuals realized the benefits of a little engineering.

“If you had a creek or tributary, you could dam it up and create a mill pond or stock pond deep enough to store timber,” said Rosebrough, who has a Ph.D. in anthropology from UW-Madison.

From there, logs could be brought to the area, and construction of a pier could begin. Once the pier was in place, ships would arrive, along with people looking for jobs. Further businesses followed to meet the needs of those workers.

The Ronk brothers — mid-1800s business owners in what was known as Ronksville, just north of Port Washington — are seen in the foreground of this undated photo of Ronk’s Pier, with workers behind.

Old underwater pilings, like these from Dean’s Pier in Carlton, are often the only remnants left of Lake Michigan’s coastal ports of yesteryear.

“They almost all had their own store. Some had their own mills, blacksmith shops and ice houses,” Rosebrough said. “The very best even had taverns, dance halls, stores selling nice clothing, and hotels.”

Some became large communities, if only for a while. “At one point, Carlton, where Dean’s Pier was located, was the third largest town in Kewaunee County,” Rosebrough said.

But the growth and success of so many of these towns wouldn’t last.

“All of these piers were fighting the elements every year,” Rosebrough said. Wind, waves and freezing waters took a great toll, often damaging the piers. “Sometimes, it just wasn’t worth rebuilding.”

In the case of Carlton, the town “succeeded itself to death,” Rosebrough noted. The owners of the pier made enough money to sell their interest in the pier and shift their focus to a successful department store business.

Today, the site of the once-bustling Dean’s Pier has only a handful of residents living on a farmstead and some quiet lakeshore homes.

More than anything, railroads were the undoing of Wisconsin’s “ghost port” towns.

“The railroads could move more goods at faster speeds and function even when the lakes were frozen,” Rosebrough said. “Many owners just gave up, people moved away, and the piers fell into disrepair.”

Without constant upkeep, the power of Lake Michigan quickly reclaimed the shorelines, and the piers of these port towns disappeared for good.

For years, many people living right next to these “ghost ports” didn’t even know about them, and the remnants of the old piers were something only known to frustrated anglers who inadvertently found them with their lures.

Thankfully, these places and their stories have been rediscovered by groups like the Wisconsin Historical Society and the Wisconsin Underwater Archeological Association.

With support from the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program, these organizations have been combing Lake Michigan’s lakebed as well as local archives in equal measure to learn more about this fascinating part of our state’s history.

Rosebrough has made a point of sharing the stories of these oncegreat communities and educating the public about Wisconsin’s storied logging and lake-faring histories.

“I’ve had the chance to speak about these ports with all sorts of groups, ranging from Zoom meetings with local forestry clubs to presenting at industry expos,” Rosebrough said. “It’s been wonderful to get to share this forgotten chapter in Wisconsin history with people.

“These places and these stories are so much more than the structures stretching into the lake and the lumber that came and went. These were the sites of real communities, of people, of families, their lives, their successes, failures, and their journeys. Those are stories worth telling.”

Where once there was a thriving community

In May, the Forest History Association of Wisconsin hosted a webinar presentation, “Hickory, Dickory, Dock: The Ghost Lumber Ports of Lake Michigan,” by archaeologist Amy Rosebrough of the Wisconsin Historical Society. Check dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1791 to watch a recording on YouTube and learn more about this forgotten chapter in Wisconsin’s Great Lakes history.

A book from the Wisconsin Underwater Archeological Association also offers more on the topic. “Ghost Port Settlements and Shipwrecks in Door County’s Clay Banks Township: A Wisconsin Maritime Study” is available for $19.95 at the group’s online store, wuaa.org.

Whether you’re a seasoned hiker or just looking for a refreshing walk with a view, Wisconsin’s trails have something for everyone, especially on a crisp autumn day.

Ready to head out on your next adventure? Consider one or all of these 14 trails you will surely fall for. Of course, we mean figuratively — so lace up those sturdy shoes or boots, watch your step and be mindful of the trail’s difficulty.

While exploring, we recommend bringing a map since cell service may not always be reliable on the trail. And though the weather is cooling off, don’t forget to bring water and bug spray to make your journey more enjoyable. Happy hiking!

Before you turn the page to read about these trails, rotate the magazine 90 degrees to the right to enjoy.

Kathryn A. Kahler is associate editor of Wisconsin Natural Resources magazine.

KATHRYN A. KAHLER

Kathryn A. Kahler is associate editor of Wisconsin Natural Resources magazine.

KATHRYN A. KAHLER

Pemene Falls Hiking Trail

Menominee River State Recreation Area, Wausaukee

1.9-mile loop. Forested, river, waterfall vistas. Natural surface, some steep slopes, rocky terrain.

Shannon Lake Green Loop Northern HighlandAmerican Legion State Forest, Boulder Junction 2-mile loop. Northern hardwoods, lake views, rocky with some steep hills.

Thordarson Loop Trail Rock Island State Park, Washington Island

5.2 miles. Circles Rock Island. Rugged and remote trail with several steep hills and a mix of forests and lake views.

Beaver Trail Pattison State Park, Superior

Sandstone Ledges Spur of North Country National Scenic Trail Copper Falls State Park, Mellen

2 miles. Circles Interfalls Lake. Boreal forest, lake views. Connects to Big and Little Manitou Falls trails.

5 miles. Remote, less developed than most state park trails. Rock outcroppings, spectacular vistas, challenging conditions.

Stower Seven Lakes State Trail Amery/Dresser

14 miles. Easily segmented into shorter hikes. Limestone surface, multi-use rail trail. Wetland, forest, prairie, picturesque lake views.

The Rock Island Ferry runs Memorial Day weekend through the second Monday in October.

Lime Kiln Trail Long Loop High Cliff State Park, Sherwood

1.7-mile loop . Mostly level, some steep climbs and stairs. Niagara Escarpment cliff environments, Lake Winnebago vistas, historical ruins.

Smrekar and Wildcat Trails

Black River State Forest, Black River Falls

Seven loops totaling 24 miles. Some segments (Ridge, Wildcat, Norway Pine) rated as difficult. Woodland, rolling terrain, scenic overlooks.

Bachhuber Loop Horicon Marsh, Horicon 2.3-mile loop. Connects to wheelchairfriendly boardwalk. Premier stopover for fall waterfowl migration. Trail Map: dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1591

Ice Age National Scenic Trail Devil’s Lake State Park, Baraboo 13.7-mile loop. Steep, rocky climbs, spectacular views of lake.

Scuppernong Hiking Trails

Kettle Moraine State ForestSouthern Unit, Eagle 11.3 miles. Easily broken up into shorter, moderate loops. Rocky, some steep climbs, roller-coaster hills, hardwood and pine forest.

Mill Bluff Nature Trail Mill Bluff State Park, Camp Douglas .4 miles. Mostly ADA accessible, hugs the base of Mill Bluff. Mesas, buttes, pinnacle rock formations.

Riverview Trail Perrot State Park, Trempealeau

2.5 miles. Relatively flat, some steps, no steep climbs. Close-up views of Mississippi and Trempealeau rivers.

Vehicle admission fees apply on state park properties. State trails and forest properties are free for hiking.

More Difficult Medium Easiest

Unless otherwise listed, you’ll find maps for these trails at: dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1486

John Minix Trail Blue Mound State Park, Blue Mounds 1-mile loop. Park’s easiest trail. Dense hardwoods.

Wisconsin’s First Capitol and a beautiful state park await

MOLLY MEISTER

MOLLY MEISTER

Driving past farmland and lush rolling hills along County Road G in Lafayette County, you may spot a couple of simple old buildings with foggy windows. Believe it or not, this is the site of Wisconsin’s First Capitol, in a small town called Belmont.

For 46 days in 1836, Wisconsin’s founders met here to establish the framework of territorial government, and 12 years later — 175 years ago — Wisconsin officially became a state. During that 1836 session, legislators also voted to relocate the capital city to Madison, so Belmont’s time in the spotlight was brief but important.

Just half a mile down the road, you’ll encounter another glimpse into history: Belmont Mound State Park, a 274-acre oasis known mostly to locals.

Its history is undocumented and, at this point, mostly anecdotal as residents, volunteers, park staff and state archaeologists work to piece together how the site was used in centuries past.

Here’s what we do know: Derived from the French “belle monte,” Belmont means “beautiful mountain.” The top of Belmont Mound is 1,400 feet above sea level, providing fantastic views of the Driftless Area, especially in fall.

The park is home to roughly 2.5 miles of scenic hiking trails, public hunting and trapping land, and a manicured picnic area for families to enjoy.

“It's a quieter park, not very heavily advertised,” explained Mike Degenhardt, the DNR parks superintendent who manages Belmont Mound. “The views from up on top are really nice.”

That sense of quiet is something Julie Abing, Belmont Lion’s Club secretary, reveres about the property.

“Capturing the view as you’re sitting on our bench that we have there or sitting in the pavilion brings a sense of calmness and relaxation,” she said.

Belmont Mound also can be a place for family-friendly adventures, added Don Berg, president of the Friends of Belmont Mound State Park.

“If you've got a family that wants to go for a hike, there are trails that are easy to do, and if you want to get a little adventurous, there are some really interesting rock formations near the top of the mound — a little something for everybody to enjoy,” Berg said.

While hiking, you’ll find remarkable Niagara dolomite formations, such as Devil’s Dining Table, and the remnants of an old limestone quarry. It’s believed stone from the quarry was used to construct buildings around the area, Berg added.

In the park’s northwest corner, the 80-acre Belmont Mound Woods State Natural Area features good examples of southern mesic and dry-mesic forests, unaffected by grazing and other disturbances common to the region. Visitors are welcome to explore the state natural area, designated in 1981, as well as the park itself.

The park is operated by the Belmont Lions Club in partnership with the DNR and the Friends of Belmont Mound State Park. Together, they are fundraising and working to make several park improvements.

Molly Meister is a public information officer in the DNR’s Office of Communications.

Belmont Mound State Park and the state natural area within it are open year-round; dnr.wi.gov/topic/parks/belmont. The Wisconsin Historical Society’s First Capitol visitor site in Belmont is open Memorial Day to Labor Day; firstcapitol.wisconsinhistory.org.

Here are a few more fun destinations in the area.

• Pecatonica State Trail: Follows the old Milwaukee Road railroad corridor 10 miles through the Bonner Branch Valley from Belmont to Calamine, connecting to the Cheese Country Trail in the east and Mound View State Trail in the west; dnr.wi.gov/topic/parks/pecatonica.

• Mound View State Trail: Gently rolling trail connects Belmont and Platteville, traveling past two large mounds rising above farm fields; dnr.wi.gov/topic/parks/moundview.

• Belmont Prairie State Natural Area: This small mesic to dry prairie remnant is located along the Pecatonica State Trail.

• Pendarvis State Historic Site: Reflects the 1800s Cornish history of the once-thriving mining community of Mineral Point, open June to mid-October; pendarvis.wisconsinhistory.org.

What does an oversized, faux fur-covered, red pinstripe-wearing, touchdown-loving, “Jump Around”-dancing, pushup-doing college mascot have to do with our state natural resources?

Everything, if it’s the University of Wisconsin’s beloved Bucky Badger.

For Buckingham U. Badger, ties to one particular state animal are well-established and date all the way to 1889, when intercollegiate football debuted and the badger began as the official UW mascot. History and tradition are as much a part of Bucky’s game as, well, the game itself.

UW-Madison’s “Bucky Badger — A Historical Look Back” notes that the live badgers first used as mascots at games weren’t the easiest creatures to control. “On more than one occasion, the live badger escaped handlers before a sideline hero recap tured the animal with a flying tackle.”

In the 1940s, one battling badger was retired to Madison’s Henry Vilas Zoo, briefly replaced by a more docile small raccoon named Regdab, or “badger” spelled backward. But that masquerade didn’t last.

By 1949, live animals were out altogether. The costumed mascot was born when UW students Bill Sachse and Connie Conrard worked to create a large papier-mache badger head, and gymnast/cheerleader Bill Sagal wore it to Wisconsin’s homecoming game.

The badger costume was based on a design drawn several years earlier by professional illustrator Art Evans, according to the Wisconsin Alumni Association’s “80 Facts About Bucky.” After trying on various names in the early going — Buddy, Bobby, Benny and Bouncy, to name a few — the mascot officially became Buckingham U. Badger following a naming contest that Sachse later admitted was rigged.

As for what that U. stands for, it’s anyone’s guess since there’s no official answer. Bucky does have an official birthday, though — Oct. 2, 1940 — when the Library of Congress copyrighted his image. And in 2006, Bucky became the first Big Ten Conference mascot inducted into the Mascot Hall of Fame.

Having a badger as the mascot for Wisconsin’s flagship university is a fitting choice for the Badger State, but that state nickname doesn’t come from the animal kingdom. As any Wisconsin fourth-grade history student may know, “badger” is a reference to the lead miners of southwest Wisconsin in the early 1800s.

The area was rich in minerals, and people of the state’s Ho-Chunk and other First Nations had long utilized these resources. Once white settlers understood the value of the land, they flocked to the territory by the tens of thousands, the Wisconsin Historical Society notes, to the point that there were enough eligible white males to vote Wisconsin into statehood in 1848.

Unmasking the mascot’s backstory and digging into his real animal inspiration

Busy as they were working their lead mining claims, or perhaps too poor to afford it, the early miners didn’t bother building homes but instead simply lived in their mines. It protected them from the elements, even in winter, but brought ridicule from others, who called them “badgers” for burrowing into the ground like animals.

The miners didn’t seem to care, according to the Historical Society. “If you know anything about badgers, you know they are tough, strong and ferocious animals. The miners were proud to be associated with such a beast!”

And so Wisconsin became the Badger State.

But what of the real animal behind all this, that notably “ferocious” beast? That’s the American badger (Taxidea taxus).

In 1957, the Wisconsin Legislature officially selected the badger as the state animal, recognizing its already existing place on the state seal and state flag. Badgers are mustelids, members of the weasel family, boasting strong, stocky bodies and long, thick claws.

UW-Milwaukee’s Wisconsin Badger Genetics Project offers more about these solitary animals:

• Badgers generally avoid interaction with humans, though they will actively defend themselves and their offspring if cornered.

• As carnivores, they eat burrowing mammals such as ground squirrels, gophers and woodchucks, plus voles and mice, ground-nesting birds and carrion.

• Highly specialized for digging, badgers create burrows that often have multiple tunnels or chambers where they sleep during most daylight hours.

• They seem to prefer treeless areas like prairies, meadows and forest edges but have been known to use

agricultural areas and even forested habitats.

• Although they might seem to be waddling as they walk, badgers are actually very mobile and may move multiple miles in a day.

• In winter, badgers don’t completely hibernate but reduce activity and spend 90% of their time in their den, or “sett.”

When it comes to the badger’s status in Wisconsin, besides state nickname and mascot inspiration, it’s no hunting allowed. While Bucky’s got game, real badgers are a nongame species in the Badger State and may not be harvested.

A gameday kiss for luck?

UW-Madison football fans and a real stuffed badger, circa 2011.

Backing badgers — and Badgers, with a capital “B” — is nothing new for the DNR. In late 1952, the agency, then known as the Wisconsin Conservation Department, even got involved in the mascot business.

To celebrate the University of Wisconsin’s appearance in that season’s Rose Bowl, the team’s first-ever bowl game, the department sponsored a 5-foot-tall animated Bucky Badger statue sent to California for the festivities. That included the 64th annual Tournament of Roses Parade in Pasadena on New Year’s Day 1953, for which then-Sen. Richard M. Nixon was grand marshal.

The statue — featuring a real badger head, dressed in a W sweater and wearing badger pelt “pants” — had been created by Hayward taxidermist Karl Kahmann especially for this event.

The battling badger didn’t help the football Badgers in the 1953 Rose Bowl game; they lost to Southern California, 7-0. But the figure did get put to other use. Upon its return to the Badger State, it was featured by the department on at least one other documented occasion, at the 1961 Wisconsin State Fair.

A DNR archive photo by Wilbur Stites shows the badger figure at the fair, with its ears a bit worse for the wear and having ditched the sweater in favor of a presumably more comfortable flannel shirt. It stands alongside a statue of Smokey Bear in Smokey’s Schoolhouse.

Warden Robert Green is there, too, to greet fairgoers, and all three schoolhouse occupants are smiling, though to be accurate, the badger’s look is more of a snarl.

All in all, the unusual historic badger bust seems to beg the question: Creepy or cute?

During the week before Thanksgiving, orange takes over the landscape in Wisconsin. We’re not talking about the changing leaves, rather the flood of hunters taking to the woods in the hopes of getting a trophy buck or perhaps a sizeable doe to fill the freezer for a few months.

Teachers change their lesson plans to accommodate students missing school. Businesses host “deer widows’ weekend” events. And stories of “da turty point buck” fill the air.

Deer hunting may be steeped in tradition, but it hasn’t always been accessible to some Wisconsinites. These days, though, the tides are changing, and new demographics are beginning to feel more welcome participating.

There’s much more work to be done, but in Wisconsin, anyone with an interest in harvesting this local, sustainable food source is invited to give it a shot.

Since the 1990s, deer hunting has changed significantly. Previously, deer were managed by habitat-based units that covered areas of similar deer herd dynamics, hunting pressure and harvest.

During the ’40s, deer in the state were most abundant in the northern forest. Starting in the ’60s, antlerless harvest quotas were established for each management unit to prevent overharvest and to allow adjustments for severe winters.

The demand for wood fiber for paper mills created excellent deer habitat in Wisconsin’s central forest zone, resulting in the prime of deer hunting during the ’70s and ’80s in that area. Shortly after, changes in the paper industry resulted in less rejuvenation of deer habitat. Deer became more abundant in the agricultural regions of the state, and many hunters adjusted their efforts accordingly.

Mild winters in the late ’80s allowed for unprecedented herd growth, even in the forested regions. Nature always finds a way to remain balanced, and deer managers began warning that the herds must be reduced by hunters before Mother Nature did it for them. But human nature being what it is meant resistance from hunters was strong.

In 1996, concerns regarding deer overpopulation — and all the potential negative things that come with it — led the Wisconsin Natural Resources Board to approve an antlerless-only hunt. Instead, the program known as Earn a Buck was created by the State Legislature as a compromise.

Three years later, despite efforts to conservatively reduce the population, it was clear deer numbers were higher than ever.

An expanding economy in the ’90s paired with a burgeoning deer population led to many hunters purchasing their own private piece of deer hunting heaven. With it came a shift in hunting strategy — hunters realized opportunities were aplenty, and they became more selective with their harvest.

“Wildlife biologists at the time recognized that the population and harvest growth they’d seen over the last decade would be unsustainable, despite the bar having been set high for hunter expectations,” said DNR deer specialist Jeff Pritzl. “It was recognized that this level of selective harvest from hunters wasn’t going to be able to keep up with the annual reproduction of the herd.”

For hunters, it would seem having as many opportunities to harvest a deer as possible would be ideal. However, for biologists, farmers, foresters and even everyday Wisconsinites, this approach came with a host of problems.

Too many deer on the landscape can result in an increase in property damage and the loss of agricultural crops. It also can cause an increase in visits to body shops and emergency rooms due to more deer on roadways.

For wildlife, larger deer populations can cause a loss of plant diversity and an increase in the spread of diseases. And it can mean deer have to compete more to find sufficient food sources.

When biologists make management decisions for Wisconsin’s deer herd, they do so within a particular deer management unit. Tracking whether a deer population is increasing, decreasing or staying stable over hundreds of square miles may be efficient, but it may not be representative of the situation in every square mile of the unit.

Deer roam and are often unevenly distributed on the landscape, depending on where resources exist. This means even in the best of years, hunters will always experience differences in how many deer they see, even within the same county or town.

From 2000 to 2008, serious efforts were made to decrease the population of deer in Wisconsin. Although intentional reduction was somewhat successful over this period, it didn’t occur evenly throughout the state.

Concern over mandated population reduction led to the creation of County Deer Advisory Councils. These resident stakeholder groups work with local DNR staff to provide input and recommendations to the department on deer management within their county.

Since 2000, 100,000 fewer hunters are participating in the annual tradition. If that pace continues, it’s anticipated Wisconsin will see another

100,000 fewer hunters in the woods by 2035.

This is not just a Wisconsin problem, it’s a national reality driven by the Baby Boomer generation aging out of hunting. Many states are faring much worse than Wisconsin.

Given these changes in the hunter population, it would be impossible to return to what hunting in Wisconsin was like in the late ’90s and early 2000s. There is no denying normal isn’t normal anymore.

“There has been a continual conundrum between the old wildlife management adage that you cannot stockpile deer for the future and the well-intentioned willingness of hunters to sacrifice the opportunity today for hopes of a better harvest tomorrow,” Pritzl said.

“Regardless of if there is truth to this or not, we must recognize that the most important management conversation we can have right now is about habitat quality, predator/prey relationships and our ever-evolving hunting culture."

About every decade, the public and the DNR step back and look at what the future holds for hunting in Wisconsin. There are certainly many possible changes on the horizon, with hunter numbers decreasing annually.

Deer hunting in the state is layered with heritage and tradition, and with

that comes an inherent resistance to change. Although Wisconsin hunters may not recall every change throughout their lives hunting, our predecessors saw the need to regularly examine our hunting systems and create new ones to meet the needs of the time.

Deer are distributed unevenly over the landscape, which affects how many a hunter might see in a given location despite overall populations. Group camaraderie is a key part of the deer hunting experience.Our challenge today is to take those same steps and ask ourselves, “How does tradition shape where we’re going?”

It won’t be an easy question to answer. In the past, the largest management hurdle was protecting the resource from overexploitation. That’s no longer the primary risk for us in Wisconsin. Fortunately, this creates a window to expand opportunities and allow hunters to find their own adventure.

For hunters and nonhunters alike, there’s a mutual interest in the issues related to an overabundant deer population — things like the garden damage they experience or seeing more dead deer on the sides of roads. Stay tuned as we look to all groups to have the difficult conversations needed to build a new hunting legacy that will continue in Wisconsin for generations to come.

Katie L. Grant is communications director for the DNR.

ISTOCK/ARLUTZ73

WISCONSIN DNR

PHOTOS BY NICK BERARD

Tree stands, scouting for deer and time together in the outdoors — Wisconsin’s deer hunting traditions encompass all these things and more.

Katie L. Grant is communications director for the DNR.

ISTOCK/ARLUTZ73

WISCONSIN DNR

PHOTOS BY NICK BERARD

Tree stands, scouting for deer and time together in the outdoors — Wisconsin’s deer hunting traditions encompass all these things and more.

It’s the year of opportunity because in 2023, there will be more antlerless permits available in most parts of the state. There’s also more late-season opportunity in the Holiday Hunt and January archery seasons, as more counties are participating than ever.

Go to dnr.wi.gov/topic/hunt/dates for a complete set of dates and unit designations.

Archery and Crossbow

Youth Deer Hunt

Gun Deer Hunt for Hunters with Disabilities^

Gun

Muzzleloader

Statewide Antlerless-only Hunt

Antlerless-only Holiday Hunt

*Season closes Jan. 31 in Metro subunits and select Farmland (Zone 2) counties; see regulations for open counties.

^Not a statewide season. More information is available at dnr.wi.gov/topic/hunt/disdeer.

** Open only in select Farmland (Zone 2) counties; see regulations for open counties.

No new deer hunting rules have been added for 2023. The full set of hunting regulations can be found online, but here are some general rules and reminders for deer season.

• Your hunting license and weapon must match. Hunting with a firearm? You need a gun deer license. Bow and arrow? Archery license. Crossbow and arrow? Crossbow license. Hunting with a bow and a crossbow? You need an upgrade to use both.

• One harvest authorization equals one deer. And be sure your harvest authorization is valid for use in the specified zone, deer management unit and land type (public access or private) where you’re hunting.

• Wear high-visibility clothing. Any time a firearm deer season is happening, at least 50% of your outer clothing above the waist must be blaze orange or fluorescent pink, even if you’re hunting with a bow or crossbow. If you’re wearing a hat or other head covering, it must also be at least 50% high visibility. Camo-blaze is legal if 50% of the material is blaze orange or fluorescent pink. We’re sticklers for safety, so we recommend that 100% of the clothes you wear hunting are high visibility.

• Check the counties in this year’s Holiday Hunt. The participating counties change year to year. See if it’s happening in your neck of the woods this year on page 11 of the hunting regulations.

• Be sure about baiting and feeding. The county restrictions on baiting and feeding can change every year and even in the middle of the hunting season, so regularly check our baiting and feeding webpage at dnr.wi.gov/topic/hunt/bait if you plan to put out some nibbles for the deer.

• Know when you can help out your friends. We’re talking about group hunting laws. During the firearm deer season, you and your friends can help fill each other’s harvest authorizations if you’re hunting together, but you cannot do so during archery seasons. When hunting in a group, you have to be within sight or voice contact at all times. Additionally, you cannot harvest a deer for someone who is not actively hunting with the party. That means everyone must be with the crew to get their deer.

• Register your deer by 5 p.m. the day after harvest/ recovery. Do it by phone at 1-844-426-3734 or online via the GameReg Harvest Report at gowild.wi.gov/wildlife/harvest.

You don’t have to be a hunter to benefit from hunting.

Hunting of game animals helps balance populations by aiding with habitat availability and by reducing the risk of disease spread. Hunting also helps to reduce property damage to vehicles, crops and gardens.

Deer hunting is beneficial to you as a commuter by helping to reduce roadkill incidents, especially in the spring and fall. Fewer deer on the landscape means less chances for them to be hit by a car.

And lastly, the funds collected from the licenses hunters purchase are used for fish and wildlife conservation activities and some administrative functions for the DNR.

Fall turkey: Statewide, Sept. 16-Nov. 17; Zones 1-5, Nov. 18-Jan.7.

Rabbit: Northern Zone, Sept. 16-Feb. 29; Southern Zone, Oct. 14 (9 a.m.)-Feb. 29.

Pheasant: Oct. 14 (9 a.m.)-Jan. 7.

Duck: Open Water Zone, Oct. 14-Dec. 12.

Hunters anywhere in Wisconsin can submit a sample from their deer to test for chronic wasting disease. Testing through the DNR is free for deer harvested in Wisconsin, and there are more than 175 CWD sample and disposal locations across the state. Find one at dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1901.

See something sketchy? Report it to the DNR Violation Hotline via call or text to 1-800-TIP-WDNR (1-800-847-9367) or online at dnr.wi.gov/contact/hotline.html

Andi Sedlacek is a publications supervisor in the DNR’s Office of Communications.

Most residents don’t have to think twice about where their water will come from every day. Still, many lack reliable access to safe water — including some using a private well with poor water quality.

That’s why working to ensure access to safe, clean drinking water is a priority for the DNR and Gov. Tony Evers.

Nearly 30% of the state’s population gets its drinking water from private wells rather than municipal water systems, putting the responsibility largely on the homeowner. Private well owners are encouraged to have them regularly tested.

Read on for what you need to know if you’re a private well owner in Wisconsin.

Everyone is potentially at risk from the three most common contaminants in Wisconsin well water, and well owners should test for these on a regular basis.

• Bacteria: Test once a year, and when you notice a change in taste, color or smell.

• Nitrate: Test once a year, and before the well will be used by anyone who is or may become pregnant.

• Arsenic: Test once. If arsenic was present in previous tests, then test once a year.

Additional testing may be helpful to look for naturally occurring contaminants in the rock and soil that could enter your well or if human-caused contaminants from land-use, plumbing materials or other sources of pollution may be near your well.

• Manganese: If you notice brown or black staining in your home or black sediment in your water, test once for manganese.

• Strontium: Consider testing for strontium if you live in the eastern or northern part of the state. Test twice over a two-year period in two different seasons, fall and spring being the best.

• Fluoride: Test when you have a baby or when you move into a home with a well. Your dentist and pediatrician will use this information to decide how much additional fluoride to recommend.

• Pesticides: Consider this test if your home is within a quarter mile of agricultural fields or areas where pesticides are manufactured, stored or mixed.

• Lead and copper: Test once every five years, or if the water will be used by a pregnant woman or baby. Lead and copper may be in your water from the plumbing materials in your home.

Regular testing ensures safety for you and your private well

• Volatile organic compounds: Testing is recommended for homes within a quarter mile of a landfill, industrial site, gas station or other underground tank, and especially if you smell chemical or fuel odors in your home.

• PFAS: Consider testing for perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances if your well is near a known source of PFAS contamination or you have reason to believe PFAS may have been released near your well. Over 450 shallow private wells not near known PFAS contamination were sampled in 2022, and 99% were found to meet Wisconsin Department of Health Services recommended safety levels for PFAS.

LEARN MORE

Find additional information for private well owners at dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1876.

Learn more about potential contaminants in your private well by visiting dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1871.

For a list of certified labs to assist you in testing your private well, contact your local health department, scan the QR code or go to dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1881.

In 2022, the American Rescue Plan Act Well Grant Program was initiated to provide funding to eligible landowners, renters or Wisconsin business owners to replace, reconstruct or treat contaminated private water supplies that serve a residence or non-community public water system well. To be eligible, family or business income may not exceed $100,000 for the prior calendar year.

The DNR will fund these grants using expanded eligibilities under this program until those funds are exhausted or December 2024, whichever is sooner. As of late June this year, 155 grants had been awarded, totaling $2,370,156.

Learn more and check your eligibility by visiting dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1886.

Apples have thrived in Wisconsin’s fertile soil for generations. From the early settlers who first planted orchards to present-day growers embracing sustainable farming practices, apples have played a significant role in Wisconsin’s culture and remain a vital natural resource.

The apple’s story in Wisconsin traces back to the 19th century, when the region’s favorable climate and soil conditions proved ideal for apple trees. As the agricultural industry grew in Wisconsin, apple growers began cultivating a wide array of apples, including favorites like McIntosh, Honeycrisp and Cortland along with heirloom varieties like Wealthy, Snow and Worcester Pearmain.

Apple orchards became a testament to Wisconsin’s agricultural heritage and growers’ dedication to the industry. Apples also have had a substantial economic impact on the state.

The apple industry contributes millions of dollars annually to Wisconsin’s economy. Orchards serve as sources of employment and tourism and also provide opportunities for small-scale businesses specializing in apple-based products such as pies, ciders and preserves.

In recent years, Wisconsin’s apple industry has shown an increased commitment to sustainable farming practices. Growers have embraced integrated pest management techniques, reduced pesticide use and adopted environmentally friendly alternatives.

Many orchards have implemented energy-efficient systems, such as solar power and efficient irrigation methods, to minimize their ecological footprint. By prioritizing sustainability, the apple industry in Wisconsin has continued to model environmentally conscious agriculture.

One Wisconsin chef has taken her own approach to assisting the apple industry with sustainable practices. Laurel Burleson, owner and chef of The Ugly Apple Café in downtown Madison, has made eliminating food waste a key priority, which is how the name The Ugly Apple was born.

Many growers deal with an overproduction of produce, which can lead to food waste. When launching her business in 2016, Burleson created relationships with local farmers and saw an opportunity.

“I wanted to bring attention to the ugly apples and the produce that’s not getting sold,” she said. “It’s still perfectly delicious and needs love.”

Produce like apples worked well with Burleson’s “quick, tasty breakfast” mantra, including favorites such as apple fritters, apple cider donuts and scones. As word spread of The Ugly Apple’s business model, more orchards began to reach out.

“Orchards kept reaching out to me on social media because of the name, and they're like, oh, you want ugly apples? (We) have ugly apples,” Burleson said.

With the help of orchards including Door Creek Orchard and Two Onion Farm, she has been able to preserve and store the fruit for use in her café for things like her fritters and fruit leather.