illumination The Undergraduate Journal of Humanities

2

Candy Darling

Brian Albarran Trujillo

Mission Statement

The mission of Illumination Journal is to provide the undergraduate student body of the University of Wisconsin-Madison a chance to publish works in the fields of the humanities and to display the talent of emerging creators on our campus. As an approachable portal for creative writing, art, and essays, the diverse content in the journal intends to be a publication for academic, artistic and community interests alike.

3

Staff

Editor-in-Chief

Poetry Editors

Samuel Wood

Nina Boals

Natalie Ketchum

Jane McCauley

Prose Editors

Olivia Dunham

Danielle Farina

Lyn Golat

Layout Editor

Staff Writers

Marley Mendez

Autumn Payette

Megan Sherman

4

Letter from the Editor

Greetings, Readers!

Welcome to the Spring 2022 edition of Illumination Journal!

I am so excited to be sharing this issue of Illumination with you. I am thrilled to be, for the first time in Illumination history, highlighting and featuring twelve student artists who were chosen by our judging panel as the winners of our first ever art and creative writing prizes. I dearly hope this tradition can continue in the coming semesters and can grow to become a comprehensive compensation model to award every student artist published in Illumination Journal some form of monetary prize.

To the new readers, who may be reading their first edition of Illumination Journal: Welcome! We are the University of Wisconsin - Madison’s home for undergraduate arts and creative writing. It is our distinct honor to showcase the incredible art that is made by students around campus, and we are so glad to have you as one of our readers. If you are a returning reader, welcome back!

I want to extend the sincerest thank you to everyone who submitted and trusted us with their work this semester. Everything we received this year was so moving, and the quality of work we received was higher than ever. It was such an honor to read all the intimate pieces of yourselves that you sent to us. Thank you for your vulnerability. Thank you for making the process of choosing the prize winners incredibly difficult. There were so many talented and deserving submissions this year that we were splitting hairs when judging who would not only win the prizes this year, but also who we had the physical space to feature in the journal. Thank you to all who submitted, you are all so inspiring, and we hope to see more of your work in the future.

I am so proud of this issue, and all our featured artists. I believe this is the strongest and most cohesive body of work we have released in recent memory, and I have loved putting it together, reading everyone’s submissions and seeing the abundance of talent, passion and dedication on this campus. I hope you all enjoy reading it just as much as the Illumination team has enjoyed making it.

Happy reading!

Samuel Wood

he/him/his Editor-in-Chief

5

COVER The Start of Something 2 Sophia Abrams 4 Candy Darling Brian Albarran Trujillo 8 transition (which rift shall act as the final divide?) Serendipity Stage 9 how are the birds? :) Azura Tyabji 11 Dead Sea Carly Silver 12 The Walk + Pedestrian Paulina Eguino 13 The Walk of Shame Aubade Aidan Aragon 14 Symbioses Allyson Mills 15 Frogs Don’t Swim in the Sea Azariah Horowitz 19 Studio Door Sheila Drefahl Contents

winners

*Prize

in red

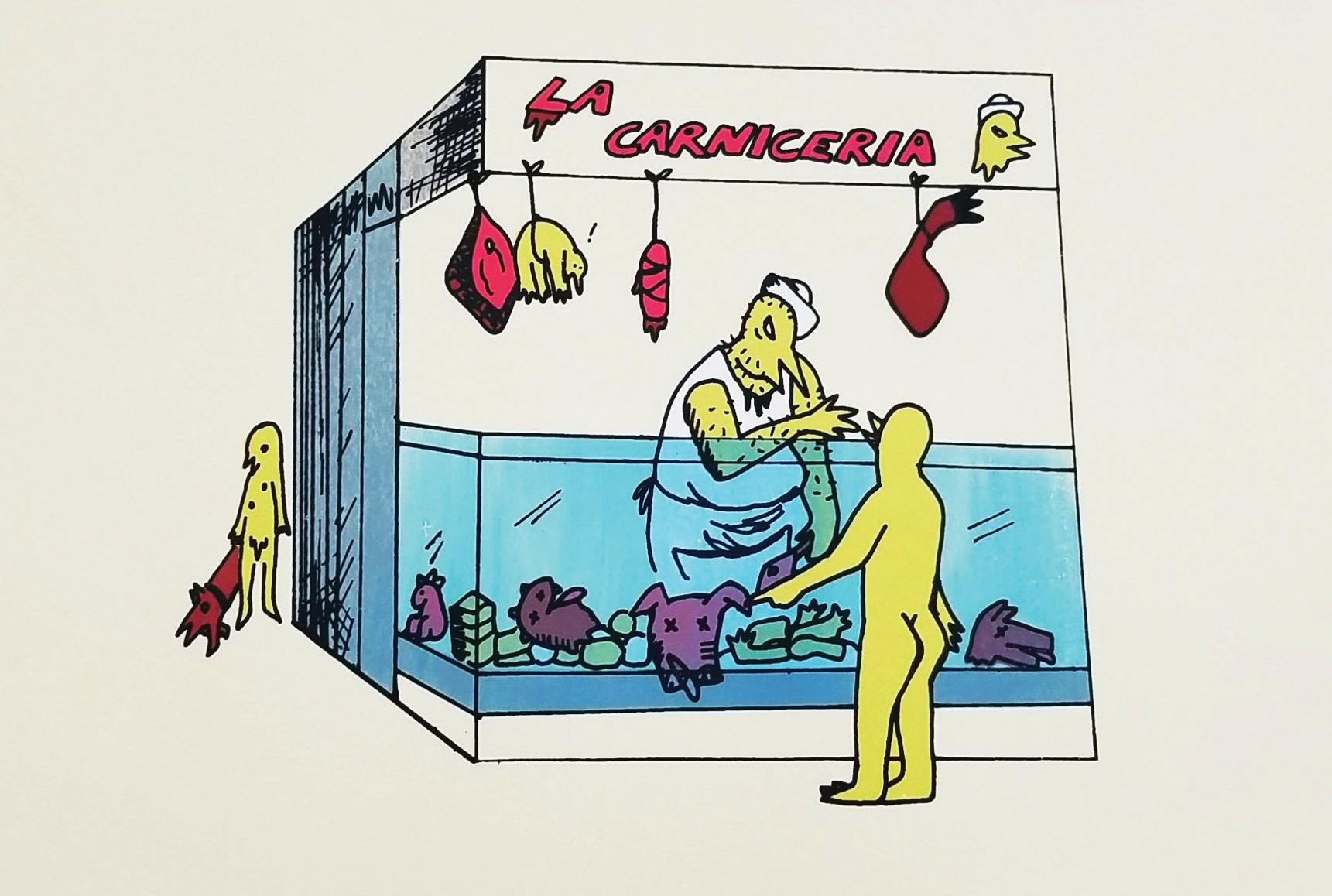

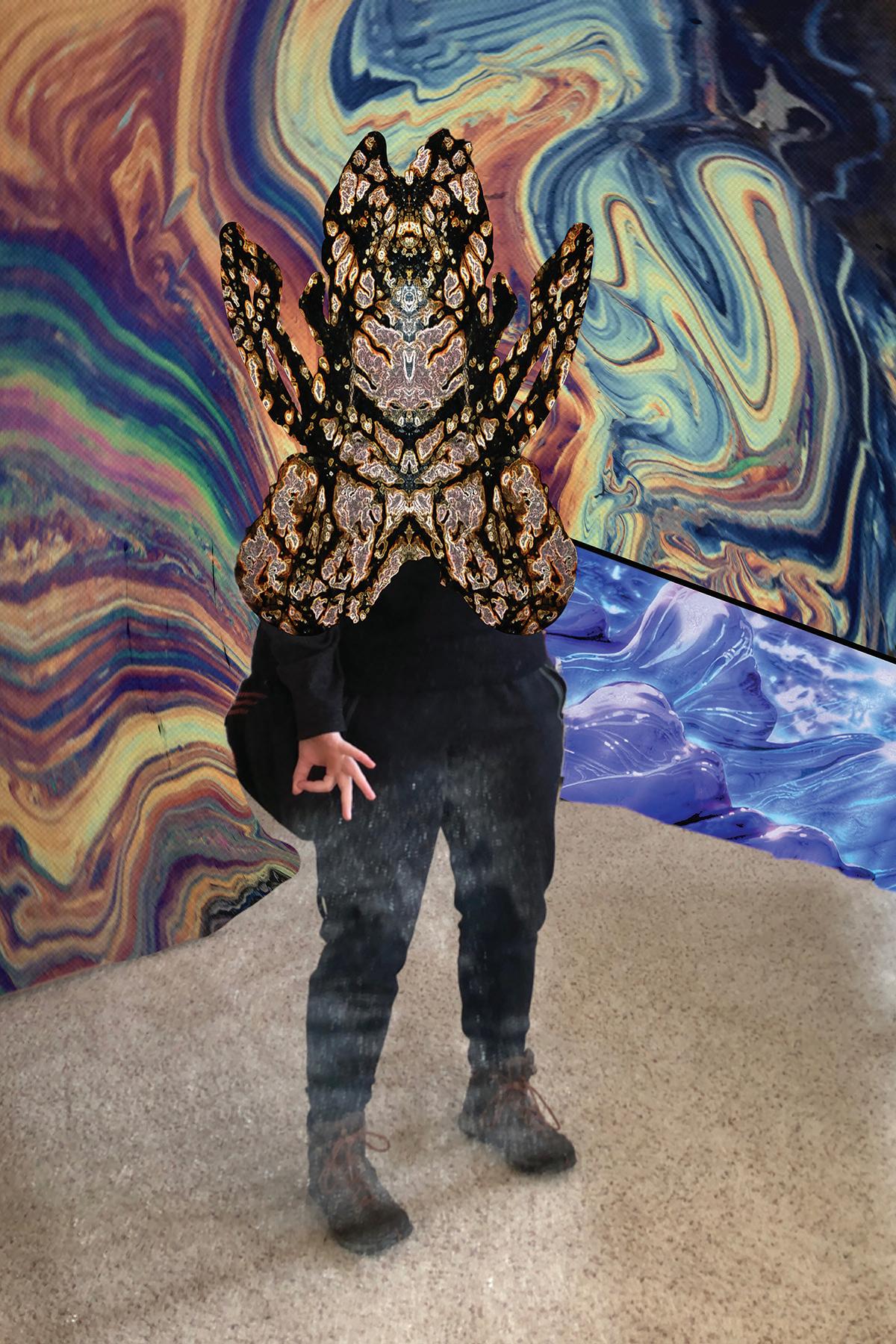

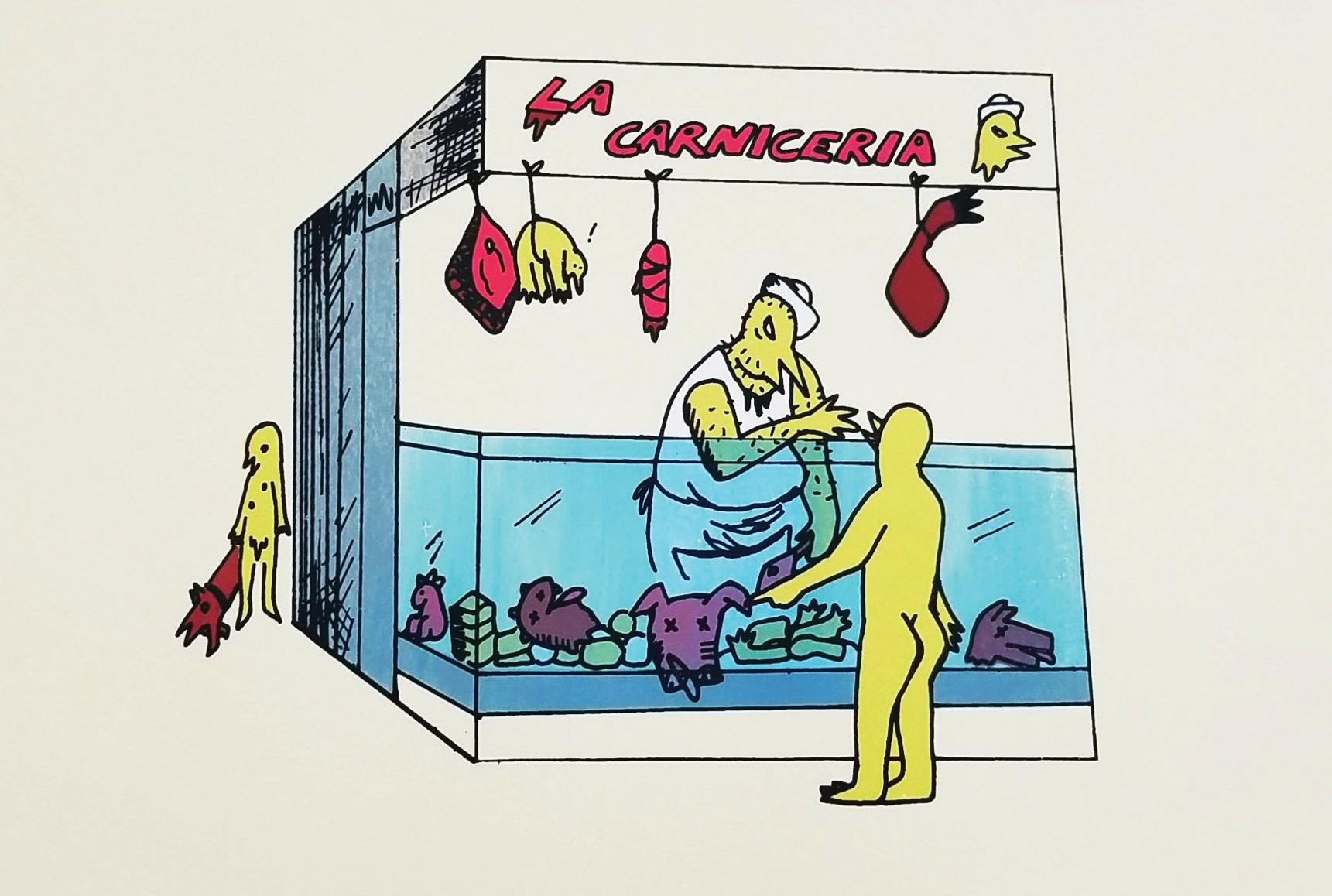

20 011001110111001001110010 Riley Scheer 21 High-budget B-List post-modern horror-comedy Arden He 22 Leon’s Frozen Custard Brian Huynh 23 Interstate 70 Phoenix Pham 25 Equanimity Brian Huynh 27 Psychic Liz Khomenkov 28 Delirium Ryan Cheng 29 The Naptime Visitor Sheila Drefahl 30 Teach a fish to climb a tree Allyson Mills 31 Babies on Candy Sarah Abbas 32 Qi Caitlyn Se 33 Little Lovers with Pink Lungs Abbey Perkins 34 CHARM Rashmi Kumar 35 Welcome Casey Phelps 41 Untitled Yahvi Mahendra 42 Meet me in your Dreams Serendipity Stage 43 lunar beast Sabrina Zhong 44 The Start of Something 1 Sophia Abrams 45 Misplaced DeOnna Garrison 46 Solace Brian Huynh 47 Time Grows Apart Emily Wesoloski 50 Portrait in Blue Isabella Covert 51 Our Town Never Had a Pool Ria Dhingra 52 5PM Izzi Bavis 54 Subzero Ruthvik Konda Untitled Yahvi Mahendra 55 Syngnathid Sam Downey 56 A Split-Second Moment of Serenity Crystal Chan 57 Fisheye Sonnet Azura Tyabji 58 Stewing Maggie Tomashek 59 reincarnation and the nitrogen cycle Azariah Horowitz 61 Chamisul Maggie Tomashek 62 La Carniceria Paulina Eguino 64 Magenta Isolation Isabella Covert 65 Six Retellings of Sisterhood Milly Maria Timm 66 Ritual to Bring a Murdered Woman Back to Life Ella Deitz 69 Agglomerated Liz Khomenkov 70 Prize Winner Bios

transition (which rift shall act as the final divide?)

Serendipity Stage

how are the birds? :)

Azura Tyabji

I’m rubbing Grandma’s feet as she watches another detective show. Arthritic, she bought this machine off Amazon to do the same thing to her hands. In old age, women become untouchable. Grandma’s calves are supple with stationary blood and I knead my worry into them. Every vein I touch maps what time will do to me. Now that I’m old, nothing matters! she laughs, pats my silly limpened hand.

We go out for brunch to celebrate January. I’m old enough to order drinks now. Grandma tells me to get bright sugared things she says she wouldn’t usually indulge in as a diabetic; grapefruit and blood orange cocktails, french toast we share from the same plate. She tells me, pressing her toast into a pool of syrup, that she was never her mother’s favorite. She was born crying and never stopped. Her mother paced the dirt floor to dust and their neighbors kicked in their ceiling. She kept howling, ignored and gumless. Teeth now petrified in a cup by her bedside. I learned very quickly that at least I could be useful, she says

as a girl she helped her mother burn toast less. She set the table for eight, corralling every son her mother pushed out shrieking after her. She shut the storm windows and prayed secretly to leave Kansas and finally be alone to cry. It is not a mother’s job to love, just to keep every crying mouth fed. We go home. I rub my fingers in Grandma’s gray. Her memory is fiercely intact underneath her hair, thin as the wings of the hummingbird she leaves sugar water out for all year. How a hummingbird finds her in the burnt heart of downtown is a miracle I couldn’t explain. Searching for sweetness,

girls become women become girls again. Age brought the freedom they dreamt of. When I realize my age, I feel like an hourglass realizing she’s hit the ground, spilling her precious sand down the drain. Soon, time will knead me free of what I wanted. Grandma’s lifetime earned her dream apartment, with the hummingbirds and oceanview and brunch around the block, and all I think about is how many corners she could fall in and not be found for a week.

The women in my family like to be alone and that loneliness has slowly petrified me. You go to sleep one night and wake up in yet another night, in your own sweat, your own dark, your own silent dreamhouse you thought you built for yourself to enjoy. No one can touch you.

I leave for college and Grandma mails me three pounds of birdseed and a birdhouse that won’t fasten on my

9

studio apartment window. how are the birds? :) she texts, and I tell her they are eating well this winter. She does not know the birdhouse is in cardboard purgatory under my bed. I throw the seeds of the ground whenever I remember to, and the squirrels look at me with skeptical interest, and the crows cry in a language I can’t understand. I rubbed lotion on the red scar the IV left in her arm and then I left. I left. There is no time left

for me to think of Grandma and not follow through on her gifts. Spring and hunger are at my table. I scatter the seeds. Some might hook on the dirt floor and grow, or at least they will be useful to something smaller than myself.

Grandma calls herself the Harbormaster for all the ships she watches come and go outside her apartment. There are two squirrels that live outside mine. A thrush of sparrows that gossip by the bike rack. The same piece of notebook paper lies at the foot of a maple, weathered illegible by storms. I was so excited one day I saw a cardinal perched alone outside my window. Bright as a pricked finger. A brief daughter of red

and then she was gone.

10

11

Dead Sea Carly Silver

12

The Walk Paulina Eguino

Pedestrian Paulina Eguino

The Walk of Shame Aubade

Aidan Aragon

The moon, a loose sequin, dangles from the sky’s slack-jawed maw

drooping lower and lower with each of my heavy-lidded blinks, feet dragging against the concrete against the inside of my ear slick

and cold from the slip of his tongue, like my satin slip creased around

my chest, cheap and smoke smooth, draping over me like the memory

of his palm indented in the curve of my step, how my thigh rubs

its sister, chafes against the memory of his palm pressed, firm, into that spot, red-pink-purpling, inches away from where he slipped

us together, the feel of my legs opening like a sunrise on a cloudless day, eyes

rubbed awake enough to slur together the door’s opening groan, a cock’s morning yelp, the yawn of his orgasm a paisley blue handkerchief

to wipe spittle from the night’s mouth, my eyes over this groggy city folding into themselves like a sock hung over the doorknob.

13

Symbioses

Allyson Mills

Frogs Don’t Swim in the Sea

Azariah Horowitz

Afternoon and the Olive Trees

Boris’s Russian Food and Gifts sits proud and washed out by the sun behind the bus stop on the corner, where Rechov Bialik meets Rechov Yehuda haLevi. In the empty lot next to Boris’s Makolet shop, stray cats stalk the dusty world between the dumpsters, and time is marked by the angle of the sun through the branches of the olive trees.

Every afternoon as the shade laps midway up the stucco wall of the Makolet, the Israeli kids stream out of the doors of Ashdod Ilanot Elementary School. They run the two blocks to the bus stop and congregate here. Older siblings pick younger siblings out from the crowd, grab onto the handles of their backpacks and don’t let go. If the bus is running late, they duck into Boris’s Makolet and blow their bus money on Bazooka bubble gum and bags of peanut butter Bamba. Then the bus pulls up and they rush the automatic doors at the back without paying.

Elya does not like this wild energy. She needs things to be steady, consistent. If she goes into the Makolet with the other kids, she will not be tempted by the chocolate, and she will not let herself buy sardines to feed the stray cats. Instead she always always must save for the bus the three silver shekel coins her Ima gives every morning. Then she will get on through the front doors, nod at the driver, and feed her handful of coins into the slot by the driver’s seat. Here, far from the chaos at the back of the bus, Elya joins the old Russian ladies at the front, the ones that remind her of her Savta, and she observes.

The old Russian ladies in Ashdod ride the bus back and forth, up and down Sderot Moshe Dayan all day long. The ones who came before sit in pairs, unravel balls of yarn slowly from their laps as they knit socks and scarves and whisper to each other in Yiddish, that language that is like folklore. The ones who came after and did not change their names greet the bus driver in Russian, clutch newspapers headlined in block Cyrillic.

As soon as she gets home from school on this Friday afternoon, Ima is already nagging Elya. Tomorrow is Saturday, Shabbat, and Elya will visit Savta bright and early. Because Savta has nothing to do, because there are no buses on Shabbat for the old ladies to ride up and down and back and forth, because the country is religious and it rests when G-d tells it to, nevermind what its people think and practice at home.

Elya finds her mother’s line of logic rather convoluted, but that does not stop her from marching up to Savta’s apartment complex in Ashdod by the sea

at 10am every Shabbat morning. She is all braids, neat white ankle socks, polished shoes, and a little floral skirt, like Eastern Europe, like the Old Country. Ima dresses her up like a doll, then sends her daughter off to bring her own mother the comfort she cannot.

Elya has never particularly enjoyed this task, but also she has never complained.

Do good deeds still count if you are doing them out of guilt?

Saturday Morning in Ashdod

Some mornings, Savta Shayna wakes up delirious and the glare of the sun on the sand outside her window is almost like the sun on the snow back in her village outside Minsk, and then she is a little girl again and she is not in exile.

But Savta does not share these thoughts with Elya. Instead, she brews tea in a kettle on the stove. Savta is precise with her time and the kettle whistles every week just as Elya is untying her shoes by the door, and: “Shabbat Shalom, Savta Shayna,” Elya says in her accent like water in a mountain stream.

“Gut Shabbos, Elyaley,” Savta responds in her accent like the earth that is soft after it rains.

They sit down at the kitchen table. The window is open to the sea and they sip their tea without speaking, like it is winter, like they need it for warmth. Elya scoops tablespoons of sugar into her mug, then swirls them around with her spoon, full of secret delight that Ima is not here to stop her. Savta puts a sugar cube between her teeth, then slurps the tea through this saccharine filter. The curtains are sunbleached and flutter in the breeze and the room smells briney, like salt.

This week, Elya is antsy. She kicks her feet against the iron legs of the table, watches their mugs reverberate on its glass top. Then, on an impulse, Elya decides she wants to take Savta on an adventure. She thinks about things she likes: feeding the cats in the empty lot with the olive trees; and she thinks about things she knows Savta likes: sitting on the bus, sitting in the bus stops, and all the other old Russian ladies who do these things with her. And Elya instantly knows what their destination will be.

Makolet One

The door of Boris’s Makolet chimes pleasantly as they step inside. Elya notices that there is no mezuzah on the doorpost, but there is a blaring red socialist flag tacked to the wall above the freezer that holds the pierogis.

15

“Shalom, Zdravstvuyte,” says Boris from behind the counter in the back of the store. He is chewing on a cigarette, reorganizing a rack of lottery tickets for sale.

Elya knows that Savta does not remember Russian. She left that place long ago, so long ago. Elya lingers by the door, examining a freezer with a slide-open top stocked full of Dadu ice cream bars imported from Eastern Europe. Savta drags her chunky white sneakers up to the counter where Boris chain smokes and presides over his little empire of black bread, vodka bottles, borscht mix.

“Privyet, dobroye utro,” Savta responds, to Elya’s surprise. Savta and Boris stumble into a conversation, they are talking Russian, but slowly so that Savta can pause to think, to untangle these words from the cobwebs that have grown around them in the back of her memory.

Then Savta makes her way around the store slowly. She picks up frozen herring cling- wrapped together in groups of six, their beady little eyes deep-frozen in place. She strolls over to a shelf of jam and honey that is made “with love from the Belovezhskaya Forest,” and pauses to take it all in in wonder.

“I am on a memory trip!” she laughs, switching into Hebrew for the sake of her granddaughter.

“How did you come to this country?” Boris asks Savta Shayna offhand, then comments that he came to Israel after the USSR broke up, and the Iron Curtain fell. Elya scoffs. She could have told you that from Boris’s Slavic clip of speech and the communist flag above the pierogis. But Boris knows that still waters run deep, and that people will talk to you if they trust that you will listen.

Savta Shayna smiles, nods thoughtfully, then opens up. “I came here from a village in the forest outside Minsk,” she begins.

Milk and Honey

Before, what was broken could be fixed. What was sick could be healed. Savta Shayna’s Mama knew this.

For a sore throat, a cough, or menstrual cramps: A spoonful of honey mixed into a cup of tea. Maybe, if this is a week of plenty, there will even be a little milk poured in. The tea cup’s ceramic sides will be warm between little Shayna’s hands and Mama’s palm on her forehead will be cold and that is good because if she has a fever, then this is serious, then Mama has time to give her love.

For a broken heart:

A cube of sugar between your front teeth. Hold it softly behind your lips and do not tense your jaw too hard when you drink or the sugar will shatter like snow. And your tea will be so sweet all at once and then it will be suddenly bitter. After all, it is only rose hips in hot water.

Shabbat Beresheet

In Minsk in the village in the forest, Shayna had a brother. A twin brother, actually. Yankle was his name.

When Shayna and Yankle wake up in their bed that is warm like the womb, there is frost creeping in through the cracks in the wood on the ceiling, and there is a shell of the thinnest ice over the top of the quilt where there are no bodies to melt it.

This morning is Friday morning, and so begins an all-day scramble to get everything done before sundown and those three stars in the sky that bring Shabbat and stillness and peace. Shayna kicks and Yankle elbows her hard in the ribs, his breath smells like sour bread. They peel back the quilt and venture out into the cold of the house. They tiptoe around other mattresses, other siblings sleeping. Mama and Papa have too many kids, it is not practical, there is not enough space, there is not enough food. But they do not think too much about this because G-d told them to be fruitful and multiply until they are numerous like the stars in the sky or the sand on the beach. The rebbe in the shul giving his Shabbat sermon does not mention that this advice was maybe not written for this family of Jews landlocked in a Russian forest, so far from G-d’s holy land on the sea.

In the cold in the morning, Yankle and Shayna wear two layers of socks, they need eggs to make challah this afternoon. The eggs are a warm and milky brown, they gather them from under the hens’ feathery bottoms in the chicken coop outside, and their breath hovers in the dawn air. Then Yankle gets to go to religious school, to Cheder to learn; and Shayna drags her feet back to the house to sweep the loose dirt off the floor and change diapers and clean spittle off round baby cheeks and help Mama sift the flour for the challah, but never braid it. She is still too little to be trusted with that. At home, playing the domestic daughter, Shayna daydreams.

On the bench in Cheder, Yankle is surrounded by boys with black curls who whisper what they are reading to themselves and rock back and forth as they work, their bodies flickering like flames. Yankle daydreams too, different dreams, Cheder dreams. They will tell each other what they thought about later, when Yankle gets home early for Shabbat.

On Friday afternoons before Shabbat comes in, Mama pours her little ones a bath in the tin tub so they will be clean and pure for the Shabbat Bride. Yankle and Shayna crunch up their legs behind them at either end of the tub, then push off the sides like frogs. Their legs are naked and their skin is smooth. They swim laps and imagine what the ocean might look like, where they say the water goes on and on and it looks like the beginning of the world when all G-d had done yet was separate out the water from the sky.

Soon the water in the tub is lukewarm and their fingers are pruned and Mama is mad that Shayna’s hair is not brushed for dinner. That means it is time to clean up and move on and maybe that is not so bad. Afterall, in the end, frogs do not get pruned toes, a fact that Yankle knows, and neither do they live in the ocean, a fact that Shayna does not know yet and Yankle never will.

16

Lively Ghosts

In Cheder, the rebbe told Yankle (who promptly told Shayna as soon as he got home), that the Talmud that Jewish boys must study isn’t just holy, it is magic! Because it is a book full of arguments between sages who lived hundreds of years apart, and yet here they are on this very page, talking to each other and talking over each other and agreeing and disagreeing. They are not dead!

“And we are so lucky to be Jews in Cheder!” the rebbe preaches to his captive audience, three benches worth of little boys, “We get to eavesdrop in on these holy men saying such holy things!” The rebbe wiggles a meaty finger and his scraggly black beard wiggles along in time.

The sages in the script argue about the sand between the tiles in a clay oven, and who is responsible for the damage of a goring ox, and lots of other mildly esoteric things that little Yankle, in all of his eight-yearold earnesty, cannot seem to muster the interest to focus on.

But yesterday, Yankle tells Shayna, he saw Rabban Gamaliel sit up on the page, shake out the dust from his beard that is even longer than the rebbe’s, and stare down Rabbi Eliezer ben Hurcanus, who dared suggest that such a clay oven is ritually pure. A page and a half later Rabbi Joshua weighs in on the debate. His eyes glimmer purpley-blue, the color of a lively ghost. Yankle boasts to Shayna that now that he has learned to spend his endless hours of Cheder in the company of Rabban Gamaliel, Rabbi Eliezer, and all the other lively ghosts, he is never bored and he is never alone.

Shayna wonders what kinds of happy ghosts live in the house with the chickens and their warm eggs, and her too many little siblings and their feathery upper lips and schmutzy baby cheeks.

Olah Chadasha // New Immigrant

When Shayna first stepped off the overcrowded ocean liner full of refugees, their silence and their sorrow, she touched down on the foreignness of a sandy soil where chaparral plants grow in solitary with their overextended root systems. And she found that she was alone. And it was strange how after so many years of praying towards this holy mythical place in the East, here it suddenly was. But that was many years ago now.

If Shayna were to go back to her village in the forest (which is already distant as a dream), she would be shocked to discover that the dampness of the earth has a distinct scent to it. A smell of ferns, and water, and life. But she will never know this because her village outside Minsk does not exist anymore now, and anyways when you grow up in a place you often tend not to notice its certain magic until you leave it behind.

A young woman now, Shayna has taken up the habit of waking up early Friday mornings to go to the open air market, the shuk, she has learned to call it in this new language. She takes the walk from her house up

the lip of the coast to the market slowly. In this new town by the sea it does not rain. There is no water in the streets, there is no water in the sky. The clouds pass over like wandering Jews, like migrating caribou, they do not stop here. In this town it does not rain and the puddles in the road are heavier than water, iridescent, stagnant. Shayna pauses to wait to cross the road, then she stays put, she does not cross, she is stuck. She watches as a little bird’s feet smack down on the surface of a puddle of oil, it thinks it can come here for a bath, to primp its feathers. Its little talons distort the surface of the oil, its colors bend blue, green, red. Shayna thinks she sees a man in the puddle, his hair grows curly and wild, it is Yankle. He is a young man now, he doesn’t swim laps like a frog in the tin tub anymore. He is muscled and kissed by the sun, not like those soft Eastern European Jews who were pale and peaceful and spent time with their holy words and holy books and then got on trains off to camps, off to die. Shayna smiles at this Yankle in the puddle. She thinks of the concerned American social workers and the other broken neighbors from Marseille and Morocco who like to ask her how she is doing, if she is lonely? Now that Yankle and Mama and the babies with the dried flour caked around their lips are gone. But Yankle is not gone, Shayna laughs. He is here. He is with her all the time. Sometimes he looks out at her from the knots on the wood of the kitchen table, the swirl of spent tea leaves at the bottom of her mug, the oil in the puddles on the street. Sometimes he talks to her, and she hears him in the wind off the sea, weighing in on her thoughts. And Shayna knows that Yankle learned these things from the happy ghosts with their black scraggly beards and purple-blue eyes. The ghosts who lived in the books in Cheder.

Makolet Two

Elya is silent now. She hangs in the quiet limbo of the makolet, a Russian paper doll in her tiny calico flowers, red against the sterile white of Boris’s tile floor.

She has never heard her Savta say these things before. Or maybe she has, but only vaguely, hinted at, but never laid fully out in the open. Really, Elya does not know so many things about her Savta Shayna. She thinks that neither does Ima, maybe. In her age, Savta Shayna is stoic and strong. She withholds. These are stories she has never offered, and no one taught Elya to ask.

Boris smiles, leans back against the countertop. He has done this before, coaxed out things kept inside for too long. He has figured out the things to say, the questions to ask. He knows how to listen.

Shayna fidgets with the bus card in her pocket. She decides that it is sudden, a rush and a scramble, and then it is peace, to tell these things. A memory of Shabbat in Minsk.

17

18

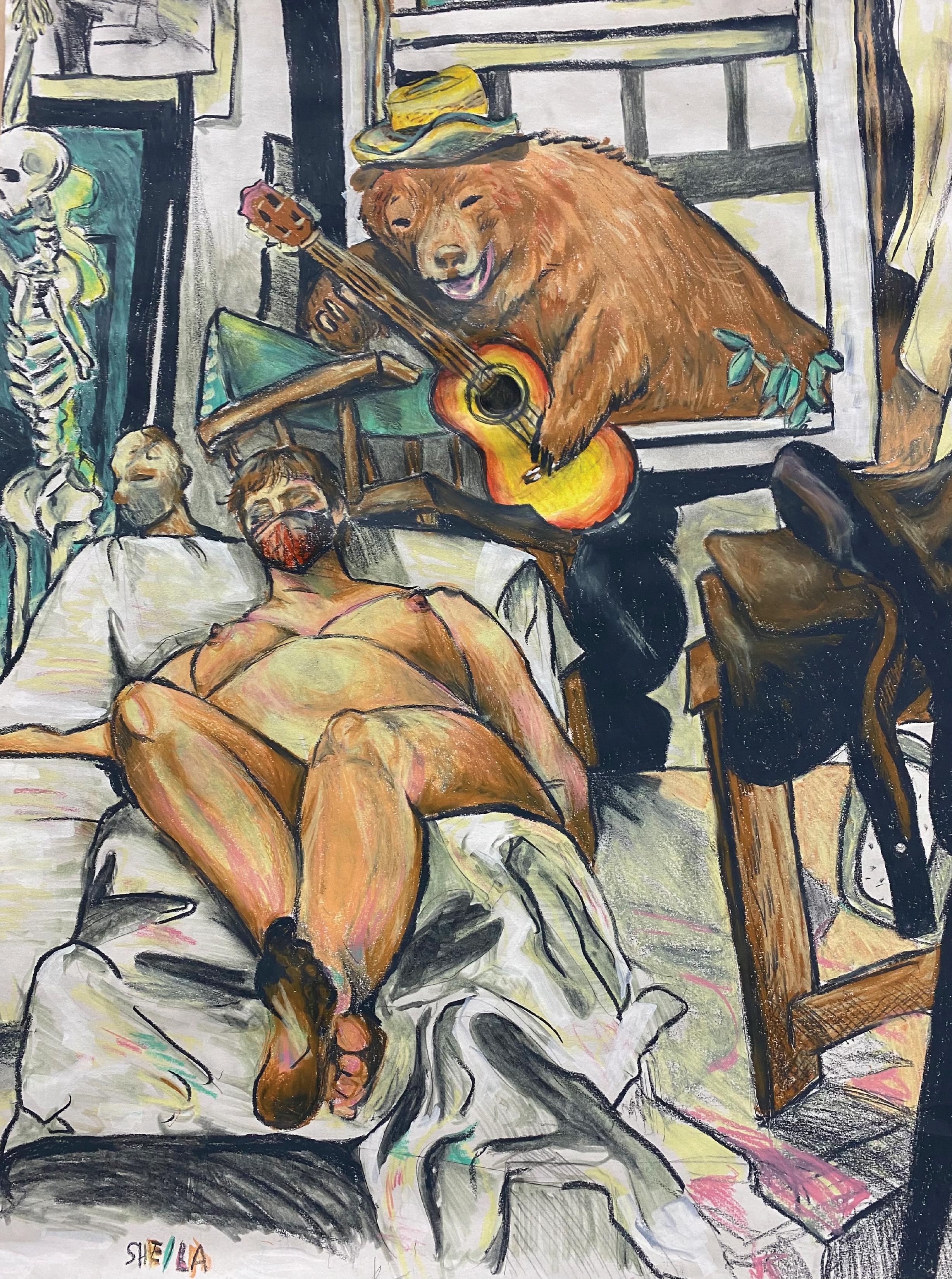

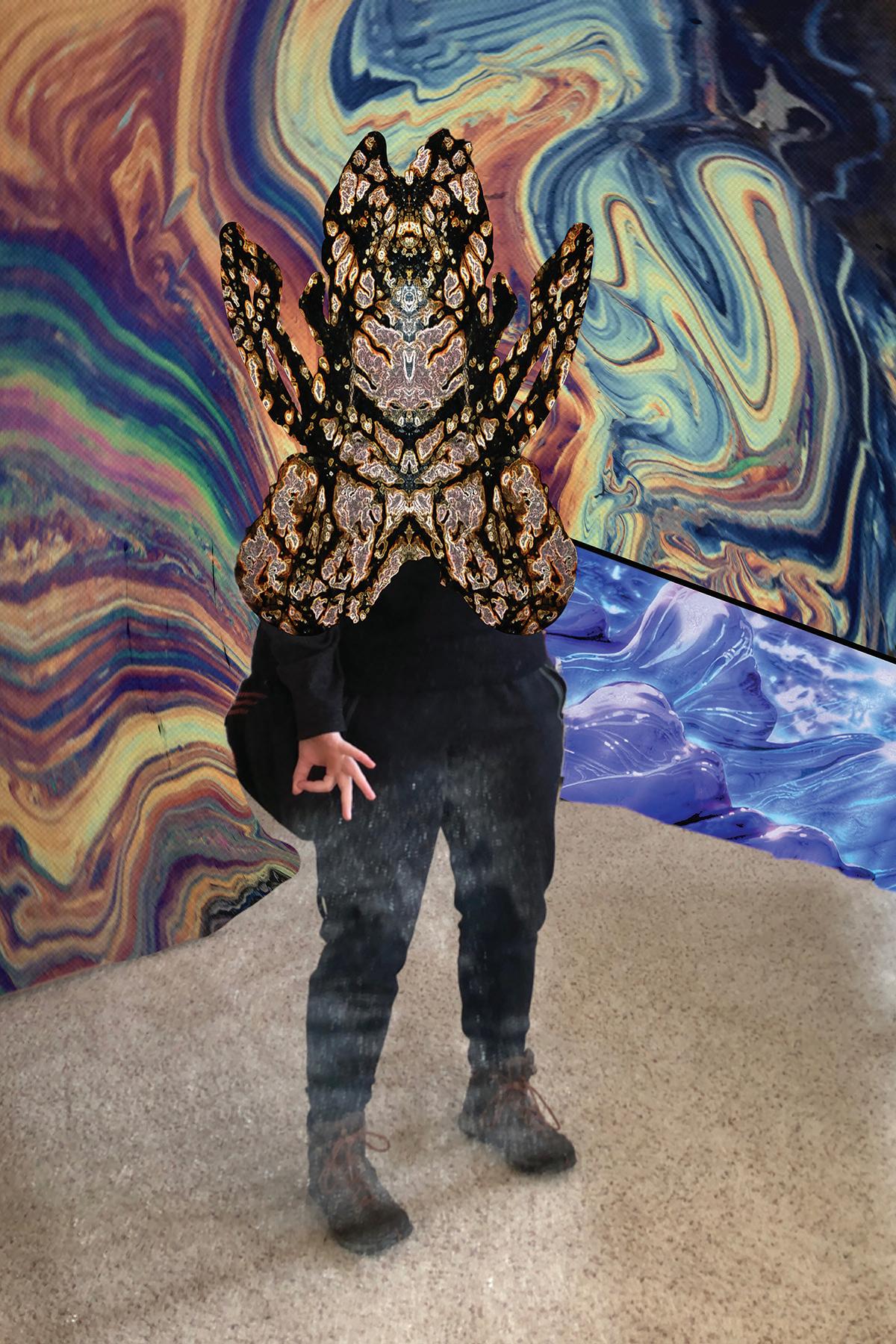

Studio Door

Sheila Drefahl

19

20 011001110111001001110010

Riley Scheer

High-budget B-list post-modern

Arden He

Somebody I loved walked into Taco Bell where the people’s hearts beat clang clang in mute horror and lunacy

& the flesh-eating bacteria had captured the capitol building & the navy pantsuits had hollowed out the banks that once held our debt flesh sweat & tears

& we were all forgiven.

Stalled to grief instead of moved to it, is how the Midwest-emo drive-through guy puts it. But the man I loved calls it atrocious joy instead.

Tell me, he said, what did Nikolai Gogol, Cixous Medusa, & God all have in common? They howled into the dark until their stomachs hurt, until tears peeled off their cheeks and they threatened to pee. BY MY WILL I WILL I LAUGH says Gogol’s gravestone, and I will. They’re

making sadness a crime, well I’m no criminal baby. I’ve been taking iPhone videos of strangers

just in case they do something I can monetize. & at night I curl on my bare bedroom floor under my collectible North Face without guilt, listening to the city burn.

Somebody I loved is selling his mom’s ring to buy a hyperlink to a number to a fragment of a picture in the ether. He’s getting a good deal. With the rest of the money he’s getting a crunchwrap, which he’s using to propose, and I’m going to say yes.

21

horror-comedy

22

Leon’s Frozen Custard

Brian Huynh

Interstate 70

Phoenix Pham

Most people assume I lost my arm during the war. Most people assume a lot of things, and most people are dead wrong. It was aliens who took my arm. It was Aliens eleven July’s ago at strange gas station here in Utah. You see, I was driving down Interstate 70. Interstate 70, you’ve been down it. It’s a straight stretch of road, sixty miles long, flatter than a sheet of paper. All you can do on a road like that is drive and drive fast. During the day it treats you to the special view of the infinite, barren, color-of-low-fat-margarine desert, and in the night its so dark all you can see is the road rolling out before you. No street lamps and no towns to break the darkness— only the stars. The stars! Like somebody set off all the Fourth of July fireworks in Texas and then just froze them there. It’s wonderful. Unless there’s clouds. If there’s clouds then it’s just dark. One thing you gotta know about interstate 70 is that the signs lie. The posted speed limit says 85, but rare is the person who goes below 100. The signs warning you that there’s no food, gas, or rest stops available for those 60 miles also lie—though not as frequently. The only time I have witnessed their mendacity was that faithful July night when I was 30 miles down Interstate 70 and, like a neon sunrise, Dave’s Cosmic Gas Station appeared.

I had been driving out of Moab to visit my ex girlfriend, Denice. She worked at a daycare up in Denver, and I was working my first summer for Capstone Raft Tours. I’d visit her every weekend. We were in love. Usually I would drive out Saturdays but I had nothing to do that Friday night, and I liked the cool air. The heat that summer had been inescapable. It was like God was a sweaty-ass aunty who just couldn’t stop hugging you. It was worse than Iraq, I swear. It was so hot that if you moved too quickly you’d collapse of heatstroke. It happened to me once. Luckily I remembered my training and killed a nearby rattlesnake for its blood— but that’s a story for another time. Anyways, driving down interstate 70 at night, it was cool enough that I could roll my windows down and forget that God was my sweaty-ass aunty. I had been driving long enough that boredom had started pushing the needle of my trusty Buick into the 110s when I saw that great neon sunrise. I pulled over. Who wouldn’t?

I considered that the gas station had always been there and I had just missed it. Ever since my tour ended, I had been known to get drifty and miss details like that. It was also possible that the station had only recently opened. But when I got closer it was clear that the latter was unlikely.

The gas station was a big, sprawling thing, styled in the way of the ‘60s, though judging from the slapdash paint job and cinder-block construction, I suspected that

it was probably just ‘90s imitation. The tin roof covering the gas pumps was painted neon green and the size of a football field. A sign saying “Dave’s Cosmic Station” in ultraviolet cursive letters hung from its side. Behind it was a building that looked as though it had been three separate structures at one point before being duct-taped together and spray-painted black. A mishmash of green and purple neon signs crowded the windows, saying “Open 4 business!” “Worlds-famous Beef Jerky,” and “ALIENS ARE REAL.”

The rest of the place was a nerd’s graveyard. There was a Delorian sitting up on bricks, a nearly-finished Millennium Falcon poking out from behind the building, and a model army of Starship Troopers soldiers surrounding the parking lot. Some of them were breathing.

Up until that point, I was in a sort of imaginative— Denice called it gullible— state. I’ve always been that way, but it really comes out at night. So I didn’t think anything strange about this gas station— until I pulled in next to the pump. You see, there was no price for gas. I’ve been fooled once before into buying gas without a price, and I was charged $216 dollars. Fucking rural Virginia. Couldn’t do nothing about it though. I just got so wrathful and I swore, up and down my soul, that it would never happen again. So, upon seeing that there was no price for gas, and thinking that this place was taking advantage of poor, tired, imaginative customers such as myself, I decided to enter the station and give the attendants a piece of my mind.

Up close, it was clear the station had seen better days. Dust clouded the windows, and the air was thick with bats. The door was so rusted that I when I yanked it open, its hinges screamed as though they were being tortured.

“Hello,” I said, even though the place looked abandoned. That’s how my house had looked when I walked in on my parents. Never again. Anyways, everything was coated in dust. The register was empty. The only lights were the neon signs, casting a green and purple glow over the rows of chips and candy bars. Only reason I didn’t leave was because the chip bags weren’t any brand I recognized. In fact, their labels weren’t in English, but in script that looked like bird tracks. I stepped inside. The door stayed open, frozen by the rust. Behind me the warm night air blew in.

“Can I get you something?” A voice said. What it really said was “CAHAHGEOOSUMFN?”, in a voice deeper than the Mariana Trench and as creaky as the door hinges. I whirled around to see a tall, skinny old man standing behind the register, wearing a tight neon green shirt that said “I am Dave” in red cursive across the right breast pocket. There were two things that stuck

23

out to me about this man. One was that he had excellent posture. I’m talking ramrod straight, like a mannequin with a stick up its butt. In fact, it was so good it was a little eerie. He didn’t shuffle, shift his weight, or do the dozens of small motions that normal people do even when standing still. It was like he was made of butter. Then there was his hair. He had enough for two heads. It was long, thick, and white, sticking out in tufts at all angles and obscuring all his face but his lips, which were cherry-red and juicy.

“How much does a gallon cost around here, oldie?” I asked. He looked at me for two minutes. Just as I was about to run out, he said,

“Have you tried our jerky?”

“No,” I said. “I have not had that pleasure.” The beer jerky here was probably from 1996. But then something strange happened: I had a sudden urge for beef jerky. The desire was so strong that I found myself saying— against my better judgement— that I would very much like to try Dave’s “Worlds-Famous” jerky. The old man pointed to the corner of the shop where there was one of those rotating metal racks that usually holds cheap sunglasses. This one had cheap sunglasses, but interspersed at random were also beef jerky packets.

“We make it in house.” He said as I walked over to the rack. I had to wipe away the dust to read the package’s titles. “Dave’s Italian Beef Jerky. Tastes like spaghetti. Dave’s Jamaican Beef Jerky: Buffalo Soldier. Mary’s Minnesotan Beef Jerky: You Betcha!” After much debate, I selected the last one, clutching it to my chest so that I wouldn’t rip it open right then I was so hungry. When I turned back to the register I screamed. The old man was right behind me. I mean right behind me— his nose was brushing mine. It was bristling with white hair. His mouth was open and I could see three, pearly white teeth: two on top, one on the bottom left. His breath smelled of rotting beans.

“Back off friend. You’re one wrong move from me jerking this jerky up your puckered ass.” I said. The old man glided back, muttering something in a foreign language (probably German). I pocketed the beef jerky and took the long way back to the register because I needed some alone time after that interaction. As I was passing the refrigerators, I noticed that they were stocked with most definitely not-American products. But these had labels I could read. They said things like “Middle-aged Ankles,” “Tongue of Kyle.” That was the final straw.

“I’m going to leave twenty dollars right here.” I said suddenly, waving a ten-dollar bill and placing it under a nearby bag of chips. “This isn’t tipping, mind you, this is overpaying. But I’m going to let you keep the change. And while you’re collecting it I’m going leave, nice and easy. Do you understand?” Another breeze pushed through the open door again, rustling the chip bags.

“The price is 20.01” Another voice said behind me. I whirled around and at first I thought the old geezer had duplicated himself, because the man in front of me looked exactly like him— same shirt and hair

and everything. As though he were reading my mind, he grinned and tapped the stitching above his right breast pocket: “My name is Also Dave”. His breath also smelled of beans.

“Do you got Venmo?” I said, eyeing the open door. I could see my Buick still parked at the pump.

“Bitcoin. Only.”

“How about one of those ‘take a penny leave a penny’ things?” Dave at the register lifted the penny tray and dumped the change into his hand. He then pocketed it and grinned at me.

“C’mon, Dave,” I said. “That was just rude.” Thinking fast, I grabbed a bag of chips, threw it at Also Dave, and ran for it. I had just made it to the threshold when the door— which, if you remember, had been frozen open with rust— slammed shut, knocking me to my feet. I scrambled up but then the geezers were on me. Also Dave grabbed me from behind and pinned my arms behind my back. His grip was stronger than good bourbon. Dave came at me with a needle and syringe the size of my forearm. I kicked at him and screamed but he knocked my legs aside and stuck me in the neck. The last thing I remembered before the blackness took me was the neon signs flickering and the station shaking. For a moment I let myself believe that this had all been a bad trip, that I was on drugs in Denver with Denice. Then I was out.

It was light outside when I came to. But it wasn’t the light of a Utah—clear and honest. This light was bloody. For a moment I struggled to put my finger on what exactly was off about the light, but then a packet of Dave’s Jamaican Beef Jerky floated past me and I realized two things at once: I was in the station’s refrigerator, and the station was in outer space. Through the floating contents of the store, I could make out a giant glowing red eye outside the windows. No, not an eye, a storm. Jupiter was before me.

We were close enough that I could see Jupiter’s famous “Great Red Spot” in action. Whirlpools and currents and eddies roved its surface, colliding and combining, and ripping apart and reforming. All happening in winds upwards of 200 miles an hour, though from the station it seemed to transpire slow motion. It reminded me of war. Then the door opened, interrupting my revery, and two figures entered. Silouhetted against the eye’s bloody glare, they appeared eight feet tall, spindly, with heads the size of beach balls. Fear flooded me and I pounded against the refrigerator’s glass door. In my panic I began tearing open the Tongue of Kyle packages, desperately hoping for a weapon but they were only frozen, human-looking tongues, only deepening my panic. Meanwhile the creatures had pushed off the wall toward me and were slowly growing in detail, their great heads resolving into halos of white hair and tanned, handsome, one-eyed faces. When they latched onto the refrigerator doors I nearly cried of relief. It was Dave and Also Dave.

After calming me down, Dave and Also Dave gave me a tour of their station. It was much more popular in outer space than it was in Utah. Aliens of all kinds

24

floated about the station. There were your classic freaks with the huge black eyes and pale skin, a couple R2D2-looking robots, and, to my utter disappointment, a Jar-Jar Binks. But there were also aliens that I had never seen before. Herds of scaled elephants. A giant hairy orb. A Chihuahua. Dave and Also Dave seemed to be on good terms with most of them. It was obvious that they were much more comfortable in outer space than they were on earth. With their hair in a halo around their beautiful faces, and at home in the zero-G, they gave me the most winsome and charming smiles, holding me gently by the arms while they led me from one attraction to the next.

The tourist attractions were much bigger than they were in Utah. There was a life-sized McDonald’s replica, with what seemed like actual humans working inside. When they saw Dave and Also Dave they ran to the windows, banging them and pleading. There were also a three frozen cows, a Titleist golfball, a giant corn palace, and a dried-up water slide. It was nice establishment, very family friendly, but I still thought it was basically what it had been in Utah: a shabby and an obvious tourist attraction.

Perhaps the Daves sensed that I was unimpressed. Perhaps if I had feigned more wonder at their orbiting attractions I would still have my arm. But I was tired, and hungry, and had stopped pretending for people years ago. After the third frozen cow I yawned and

motioned at Dave for something to eat. He looked me in the eyes with his big, single eye. It was gold and full of hurt. After a moment he patted my stomach, smiling sheepishly and gestured at the Wonalds. But then Also Dave grabbed his arm and whispered something to him. Dave smacked his forehead and laughed, and when the two turned to me they were smiling again. I pointed at the McDonald’s hopefully, but Dave held up a finger as if to say “One more” and led me back to the station. They tucked me back in the refrigerator and gave me a Coca-Cola. I do not believe it was any cola that they sell in the States, though, because no cola since then has made me feel such a warm and buttery calm as that cola did. The high stuck with me even when Also Dave appeared from the back of the shop with a small light saber. Even when they opened the refrigerator door, exposing me to the vacuum of space, and cut my right arm off was I at peace. There was no blood because the lightsaber cauterized it. They put me back in the refrigerator and I went to sleep.

When I woke up, I was back in my old red Buick, pulled over on the side of the interstate. The dashboard clock read 3:17am. Everything was how it had been when I pulled into Dave’s Cosmic Station, except my arm was gone. Skin was covering it as though I had lost it years before. Dave and Also Dave must have had given me some alien healing agent. Now I’ve said I’m an imaginative person. I do get drifty sometimes, and so I

25 Equanimity Brian

Huynh

was prepared to admit that hte whole thing was a dream, that I had lost my arm in the war like they said, but then I checked my pocket. Inside was a dusty packet of beef jerky. Its packaging read “Mary’s Minnesotan Beef Jerky: You Betcha!”

Despite knowing everything I had just seen, I couldn’t help myself but to a couple bites. If anybody deserved some beef jerky, it was me. And let me tell you, it tasted sublime. I still have a morsel left over. One day I might bring to a coroner to track down who it belonged to, but I’m afraid that may land me in more trouble than good. That’s why I didn’t tell Denice that I had proof, that I know for certain that it wasn’t a dream. I only tell you, traveler, because you should be warned about driving on Interstate 70 during the night.

26

Psychic Liz Khomenkov

Delirium Ryan Cheng

You wake, and it is six-thirty on a Monday morning, and the sound of your alarm is sending little waves of revulsion into your brain, and the sun through your window is a flash-bomb thrown at you from heaven with love, and the melatonin is seeping from you like sand dragged back into the ocean but you fix a smile to your face with toothpicks and you down your coffee like it’s the nectar of the gods and it really is when you’re far enough gone to be mainlining the caffeine into your bloodstream but before you can

You wake, and it is pitch black and hot as hell and the sweat soaks through your shirt and your blanket and there’s probably puddles there maybe with alligators, and you peel it off you like the wet pages of a library book about the Ruminant Animals of America, and you lurch up and check your clock and 6:65 glares back at you in LED hate, and you check your phone and it’s Saturday and you say Oh Good but your blinds are glowing red so you throw them open and your lawn is on fire and and you say Oh God and everything is on fire and the floor trembles with the mad laughter of the deathrow-free and it’s your laughter and then

You wake, and you’re climbing Mount Everest to find the Sage of the Immortal Mysteries, and the wind burns cold on your skin and howls like it hasn’t had a day of nice summer weather in four billion years but you’re used to it, born and raised in Wisconsin, and your toes find the safe places in the rock and you pull yourself over the ledge and into the cave and see the Sage of the Immortal Mysteries but it’s just a goat and you say Sage of the Immortal Mysteries Grant Me Your Wisdom but it’s just a goat so it says Maah and you say Bruh and it trots over and gnaws on your face and as the saliva drips down into your eyes you see stars dropping into an empty pond like overripe plums and cosmic eggs forming in the middle of black holes like bezoars and it’s all so simple and

You wake, and you’re in class and the teacher is droning on about Kafka on the Shore, and as you wipe the drool off your desk you see alligators and mysteries and a weekend ocean, and you put your head down cause you need to get back there and the teacher calls on you and you don’t have any pants on but you don’t care even though everyone’s laughing and you shut your eyes and it’s all dark on the inside of your head but there’s still alligators and mysteries and a weekend ocean and you can’t fall asleep so

You wake, and you’re in the break room and you watched Inception last night and If You Tried To Interpret This You’d Probably Go Insane but you do it anyways cause you really couldn’t care less about internal auditing at 1:30 pm after lunch, but it doesn’t mean anything so you go on with your boring life, and maybe you have a midlife crisis but that’s about it, and then you die.

28

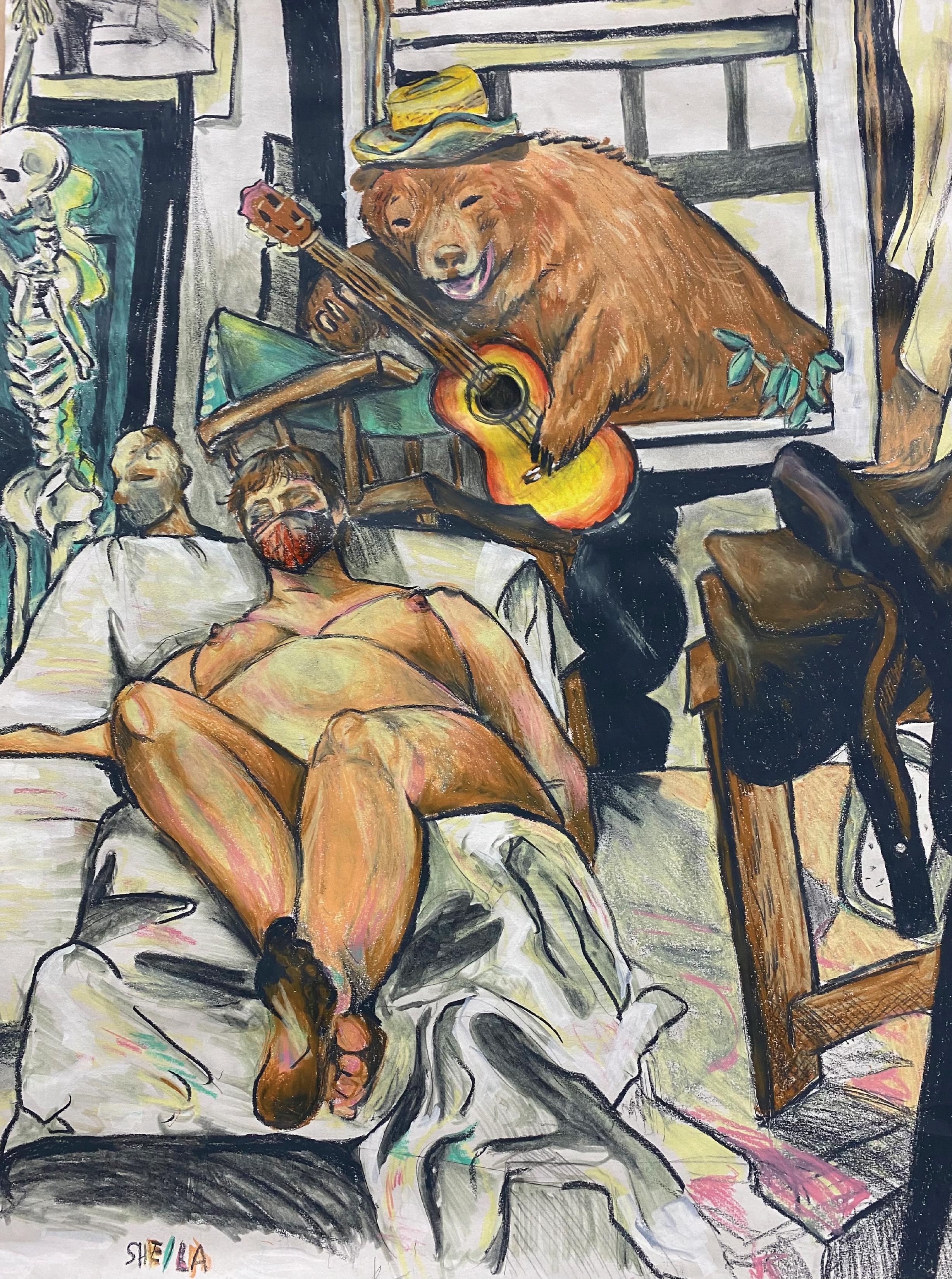

29

The Naptime Visitor Sheila Drefahl

Teach a fish to climb a tree Allyson Mills

Babies on Candy

Sarah Abbas

a bandit of children mistook a square speckled paper for treasure and now they are wringing out their knees to a song at a volume only they can hear. at this age, they don’t know of God but saw him in the woods snacking on the shell of a tree the core of the sun in a bowl of fruit a band of cicadas as the end of all days. who taught these apple-pie babies to spell DIETHYLAMINE to crawl up the same walls looking for a window to climb through they found it hours ago and haven’t stopped jumping out looking for exits turning into signs they can’t read they’re too young to have had enough already under the half moon’s googly looking the rose bushes that dance on command flowers will dig for their kin light bulbs will balloon and paint all the rooms green and lamps will chase them up the stairs until they can get the walls to breathe in the same lysergic looking.

31

Qi Caitlyn Se

Qi Caitlyn Se

Little Lovers with Pink Lungs

Abbey Perkins

life is meant to be romanticized. so, let’s cry to the sky tonight, those stars glitter as our tears shine. let’s feed the fish and hug the cats in the alley; twirl in the rain with nothing on but our boots and undies. let’s drive aimlessly through alleyways and backroads, the streets as open as our hearts and minds oughta be. let’s talk each other’s ears off, make outrageous claims so they’ll call us insane. synonymous with free thinker, let’s think freely. free ourselves. life is meant to be romanticized. bird chirps are symphonies, mother’s tea the elixir of life. the sun is our god, the moon her concubine. let’s breathe life into the mundane and find love at a coffee shop. let’s get married under a sycamore tree and eat little cupcakes with white frosting. let’s fall into infatuation with strangers in target and write about them before bed. let’s slow dance in the chip aisle. let’s be kids until we’re 80 and outline our wrinkles with pastel colors. we will be hopelessly romantic until our time expires, as we should. as we are destined to.

we’re wed to our lives

honeymoon phase for always little things fulfill

33

34

CHARM Rashmi Kumar

Casey Phelps

While having breakfast in bed, as he had had every morning since the accident, Caro was startled by a peremptory rapping at his door. He lowered his cup of tea from his lips and promptly rejoined: “Just a moment, please.”

He recapitulated the cup on the tray next to the eggs benedict and hash browns and the napkin with the cutlery on top and the orchid in its vase. After placing the tray on his bedside table for later consumption (as he, a politely diffident man, rarely ate in the company of strangers) he shifted his weight to the opposite side of his bed to face his chest of drawers.

The knocking grew more intense.

“Just a moment.”

As he was above the covers, the ghastly stump that was once his leg, wrapped in a bloodied gauze, lay exposed. Opening a dresser drawer he removed his new pants, given to him by his cousin Marcus, with the left leg cut off halfway and sewn shut. He never wore them alone since he had lied about his waist size (feeling particularly vulnerable since the accident) and as a result the pants were far too tight for comfort, but they were all he had for the time being.

As he struggled donning the new pants the rapping continued.

Knock rap rap rap... Rap... Knock rap knock rap... Rap knock... Rap rap knock... Rap rap rap... Rap……. Rap rap……. Knock rap knock rap… Knock knock knock… Rap rap knock… Rap knock rap rap… Knock rap rap……. Knock rap… Knock knock knock… Knock……. Rap rap rap… Knock... Knock knock knock… Rap knock knock rap……. Rap rap knock rap… Knock knock knock… Rap knock rap…….

“Please, please, I just need one moment!” Caro responded with increasing anxiety, but the knocking continued inexorably, much to the discomfort of poor Caro.

“Is it an emergency?” Caro asked, as he fumbled with the pants. There was no answer. He was never able to get the button fastened, so he settled for pulling his shirt down over the waist and hoping the oncoming visitor would fail to notice. He answered.

“Oh, come in.”

The knocking continued.

“I say, you may enter!” he said a little louder, but the knocking did not cease. Caro shouted “You can come in!”

Knock rap rap… Rap… Rap knock… Knock… Rap rap rap rap– Rap rap rap rap… Rap……. Knock rap knock… Rap rap… Knock rap… Knock rap rap… Rap knock rap rap… Knock rap knock knock……. Rap rap rap... Knock… Knock knock knock… Rap knock

rap……. Knock knock… Rap–Caro slumped down, nonplussed. There was someone knocking on the door, wasn’t there? Maybe someone was hammering in another room. No. No, he wasn’t having any work done on the house. It was his own house after all, he should know, and he had the right to know who was making all this racket in his own damn house.

Knock… Rap rap rap rap… Rap……. Knock rap knock rap… Rap knock… Rap knock rap… Rap knock Rap… Rap rap… Rap knock… Knock knock rap… Rap……. Rap rap rap rap… Rap… Rap knock rap rap… Knock rap rap……. Knock rap rap rap… Rap rap knock… Knock... Rap knock knock knock… Rap rap knock… Rap rap rap… Knock……. Knock knock knock…

Caro searched with his eyes for his crutches. They were lying on the mantle, far on the other side of the room. He had always had a terrible sense of balance, which now rendered him practically immobile since the loss of his leg, and his crutches were his only hope for getting around. The visitor was going to have to let his or her self in.

“The door is unlocked …. Please… please let yourself in.”

The knocking continued.

“Hello?” Caro asked, desperately. Rap rap knock… Rap knock rap… Rap rap rap… Rap… Rap knock rap rap… Rap rap rap knock… Rap… Rap rap rap– Rap knock… Knock rap… Knock rap rap……. Rap rap… Knock Knock… Knock knock… Knock knock knock… Rap knock rap… Knock… Rap knock… Rap knock rap rap… Rap rap… Knock… Knock rap knock knock.

“Dreadful knocking.” Edmond later said, at tea.

“It’s been going since morning.”

“My god, that long?”

“Since breakfast.”

“Moses, is that why you haven’t eaten?” Edmond motioned to the uneaten eggs benedict, hashbrowns and tea at Caro’s bedside.

“Yes. You know I can’t eat around other people. I’m shy that way.”

“Yes.”

“I just wish they would let themselves in and get on with it.”

“You must be ravenous. You should really go ahead and eat, darling.”

“I’m really not hungry anymore. This whole knocking business has made me very nervous. Stomach’s upset.”

35

Welcome

“Can’t. Don’t have me crutches.”

“Well where are they?”

“There, on the mantle.”

Edmond, sitting by the fire with his cup of tea, looked up at the mantle to find the crutches there looking back at him.

“Ah.”

“I can’t reach them from here.”

“Mhmm.”

“I can’t get anywhere without the damn things.”

“I see.” Edmond sipped his tea loudly. Rap knock knock… Rap……. Rap rap rap… Rap knock rap rap… Knock knock knock… Rap knock knock… Rap knock rap rap… Knock rap knock knock……. Knock rap rap… Rap knock rap… Knock knock knock… Rap rap rap knock… Rap– Rap rap rap rap… Rap……. Knock rap knock… Knock rap… Rap… Rap knock knock……. Knock rap… Knock knock knock……. Rap rap rap rap… Rap knock… Rap rap rap… Knock… Rap Rap Knock…

That night, Caro had much trouble trying to sleep. The knocking went on and on. He lay there in his bed, the covers scattered, his new pants still on, tossing about in frustration. He turned on his side and grabbed his alarm clock from the table, positioning its face beneath the moonlight. Thirteen minutes past three. He set it back down and looked to the door.

Knock rap… Knock rap rap……. Rap rap……. Rap rap rap rap… Rap knock… Knock rap rap……. Rap knock knock rap… Rap rap knock… Knock……. Rap knock… Rap knock knock… Rap knock… Knock rap knock knock…….Knock knock… Knock rap knock knock……. Rap knock rap rap… Rap knock… Knock rap rap rap… Knock knock knock… Rap knock rap……. Rap knock… Knock rap… Knock rap rap…….

“Hello?” Caro asked, once again.

Knock knock… Knock rap knock knock……. Rap knock rap rap… Rap… Rap rap… Rap rap rap… Rap rap Knock… Rap knock rap… Rap……. Knock… Knock knock knock… Knock knock knock, … Rap rap knock rap… Knock knock knock… Rap knock rap……. Rap rap rap rap… Rap rap… Rap rap rap……. Knock rap knock rap… Rap rap… Rap rap rap knock… Rap rap… Rap knock rap rap… Rap rap… Knock… Knock rap knock knock–

“Would you just come in already?”

Rap knock knock… Rap……. Rap knock knock rap… Rap knock… Rap rap rap...Rap rap rap… Rap… Knock rap rap……. Knock… Rap rap rap rap… Rap……. Rap rap rap… Knock rap knock rap… Rap rap rap rap… Knock knock knock… Knock knock knock… Rap knock rap rap, ... Rap knock knock… Rap rap rap rap… Rap… Rap Knock rap… Rap……. Knock rap knock rap…

Caro took a pillow and wrapped it around his head, pushing it close against his ears, but this did very little to muffle the noise.

Rap rap rap rap… Rap rap… Rap knock rap rap… Knock rap rap… Rap knock rap… Rap… Knock rap……. Rap rap rap… Knock… Rap knock rap… Knock knock knock… Rap rap rap knock… Rap……. Rap knock… Knock……. Rap knock rap… Rap… Knock rap knock rap… Rap… Rap rap rap… Rap rap rap–….… Rap rap… Knock rap……. Knock… Rap rap rap rap… Rap……. Rap knock rap… Rap rap… Knock rap… Knock knock rap–

“Has it healed yet?” Caro’s father asked.

“Not quite. The doctor will be here later to change the bandage.”

“Freak thing, really.”

“What?”

“The business with that lion. Chewing your leg off and all that. Really came out of nowhere.”

“I wouldn’t say that.”

“Really, why not?”

“I was hunting it, wasn’t I? I would think it came with the territory.”

“It was a surprise to me, anyway. You really should think to tell your own father before going on an African hunting expedition.”

“It was only fair, wasn’t it? I was trying to kill the poor girl. I came thousands of miles, just to shoot her. Awfully rude of me. I should be thankful she only took a leg.”

“This is why you hire an expert, don’t go out there by yourself. You can’t take on the world all by yourself, you know. You’re not bloody Allan Quatermain.”

“I did hire an expert. A whole team of them. Game hunters. We were all attacked.”

“Well I didn’t know that. You should really tell your father these things.”

Rap knock knock… Rap……. Rap knock knock rap… Rap knock… Rap rap rap… Rap rap rap… Rap… Knock rap rap……. Knock… Rap rap rap rap… Rap……. Rap rap knock rap… Rap rap… Rap… Rap knock rap rap… Knock rap rap… Rap rap rap……. Knock knock knock… Rap rap knock rap……. Knock knock rap… Rap knock… Knock knock rap rap… Rap rap… Knock rap… Knock knock rap…….

“And now with this damn knocking. It can’t be good for your recovery.”

Caro sighed. “It’s certainly making me uncomfortable.”

Knock knock rap… Rap knock rap… Rap knock… Rap rap… Knock rap–Rap knock knock… Rap……. Rap knock knock rap… Rap knock… Rap rap rap… Rap rap rap… Rap… Knock rap rap……. Knock...Rap rap rap rap… Rap……. Rap rap rap… Rap… Knock… Knock… Rap rap… Knock rap… Knock knock rap……. Rap rap rap… Rap rap knock… Knock rap–

36

At dinner, Caro’s father cut his steak and drank his

whiskey.

“You should really eat something, my boy. It’ll calm your nerves.”

“No. I can’t eat. Not when I’m so uncomfortable.”

Caro’s father continued cutting. “At least have a drink. Good for you.”

“I just wish I knew who it was.” Caro said. Knock knock knock… Cut knock cut……. Cut knock cut… Cut knock… Knock… Cut cut cut cut… Cut… Cut knock cut– ……. Cut cut cut cut… Cut……. Cut knock knock cut… Cut knock… Cut cut cut… Cut cut cut… Cut… Knock cut cut……. Cut cut knock… Cut cut cut–

“Who could it be behind that door?” he continued.

Knock… Cut cut cut cut… Cut……. Knock cut cut… cut… Cut knock knock… Cut cut cut……. Knock cut cut… Cut knock cut… Cut… Cut knock knock……. Knock knock cut knock… Cut cut knock… Cut cut… Cut cut cut Knock… Cut…

“I remember, when I was a boy,” Caro’s father said, “We had an old priest, an old, old man he was, and he used to come to our house every Sunday morning, early, early. And he would knock on the door and invite us to mass. We were the only family, you see, that didn’t go to church. Only family in the whole town. What was his name? Father O’... Father O’ … Father O’ something… Father O’–”

“Goldstein.”

“Father O’goldstein? That can’t be right.”

“No, Arnie Goldstein. My landscaper. He said he would stop by after my return from Africa. Maybe he’s the one who’s knocking.”

Cut chew cut… Cut cut… Chew cut… Chew chew cut……. Cut chew… Chew cut… Chew cut cut……. Chew cut chew cut… Cut cut cut cut… Cut cut… Cut Chew cut cut… Cut chew cut cut–Rap rap Knock rap… Knock knock knock… Rap knock rap……. Knock knock knock… Knock rap… Rap

knock rap rap… Knock rap knock knock……. Knock knock rap… Knock knock knock… Rap rap rap… Rap rap rap… Rap knock…

“Arnie, is that you?”

Knock knock… Rap... Rap knock rap, …….

Knock knock… Knock rap knock knock……. Knock

knock rap… Knock knock knock… Rap knock knock…

Knock rap–

Knock knock… Knock rap knock knock……. Knock…

Rap rap… Rap knock knock rap… Rap knock knock rap… Rap… Knock– ……. Knock knock knock…

Knock rap… Rap knock rap rap… Knock rap knock knock……. Knock…

Caro’s father laughed.

Rap rap knock… Rap knock rap rap… Rap knock rap rap… Rap–…Rap knock knock… Rap……. Rap knock knock rap… Rap knock… Rap rap knock…

Rap rap rap… Rap… Knock rap rap……. Knock rap rap rap… Rap… Rap rap knock rap… Knock knock knock… Rap knock rap… Rap……. Rap knock…….

Rap rap rap rap… Chew chew chew… Cut cut chew… Cut cut cut… Rap…….

“The marigolds are in particularly bad shape.”

Caro nodded.

“Actually, the hibiscus is the worst,” the landscaper added.

“Is there anything that can be done?”

The waitress came by and filled Arnold Goldstein’s champurrado (A warm chocolate flavored masa beverage).

“Thanks, doll.” She rolled her eyes and walked away. Arnold continued. “I’m doing all I can for now. I got guys watering and resoiling around the clock. I really should have come sooner, I apologize.”

“I thought maybe you were the one knocking on my chamber door this whole time.”

“Oh you mean that knocking?” Goldstein said, pointing up in the air.

Knock. Knock. Knock. Knock. Knock.

“Yes, it’s been going for some time now.”

“You don’t know who it is?”

“No. Could it be one of your men?”

“Nah, my guys never enter the house without my permission. They always consult me first. If one of my boys charged into a client’s house, started knocking on their bedroom door, I’d send ‘em home with a pink slip—like that.” Arnold snapped his fingers. “This knocking though, it seems to cause you great discomfort.”

“It’s nerve-racking. Having someone knock on your door all hours like this. Never revealing themselves. Never even speaking.” Caro scanned the cafe. Patrons abound were holding their hands against their ears, shouting over the noise, wincing in mutual annoyance. “Sometimes flowers react, psychologically to their owners.”

“What?”

Arnold shouted over the knocking: “If you’re experiencing discomfort, it could be taking a toll on your flowers! This might be why they’re wilting!”

Caro fell back against his pillows. “You really think?”

“What?”

The waitress dropped the check off on the chest of drawers. She yelled at Caro, “Are you sure I can’t get you anything?”

“Nothing for me, thank you. I can’t have anything because of the nerves.”

The Waitress nodded. She went back behind the counter and put on a pair of earmuffs she removed from underneath the register.

Doctor Stravinsky returned holding a manilla folder, thick with x-rays and notes, and sat at Caro’s bedside.

“Thank you for coming, Mr. Caro. I’m gonna give it to you straight, my friend. It doesn’t look good.”

“What is it, doctor?”

37

“It’s a very very very rare disease. I don’t even know what it’s called.”

“What? You don’t?”

“I have it written down somewhere here.” Stravinsky fanned through the folder to no avail. “Anyway, it doesn’t matter. You already have it. And it’s advanced quite a bit.”

“Moses.”

Doctor Stravinsky rose and approached a lightbox affixed to the wall, onto which he fitted one of the x-rays.

“As you see here,” The doctor removed a baton from his lab coat and pointed at the image of Caro’s skull, which had two black spots where his ears should be, “It started here. In the ears.” He removed the x-ray and positioned a new one, displaying Caro’s neck covered in black spots, “Then it spread through the throat,” he replaced it with another x-ray, with more black spots “then took over the lungs, the stomach, the liver.” another x-ray, more black spots “It spread through your left arm, all the way to your fingers,” another, “then your right arm, same thing,” another, “then your intestines,” another, “then your right leg,” another, “then your left leg— er, what’s left of it, rather.”

“I don’t remember taking all these x-rays.”

“Soon it will spread back up to the brain and then you’re done, baby.”

“But what-”

“Game over, son.”

“But-”

“You’re through.”

“Yes, but-”

“Dead, dead, deadski.”

The knocking continued.

“Yes, doctor, but there must be something we can do.”

“No.”

“Nothing? There’s no treatment? What do people normally do?”

“They don’t ‘normally’ do anything.” the doctor exclaimed, accompanied by finger quotes, “There’s nothing ‘normal’ about this. Like I said, this is a very very very rare disease. We don’t know anything about it. I don’t even know what it’s called, remember?”

“I just don’t under-”

“Doctors don’t know everything, you know.”

“I know, I just-”

“You’d actually be surprised at how little we know. There are a lot of areas where science is lacking. Humankind is still young in this respect.”

“Yes, but what would you advise? There must be some plan of action.”

“We’re all just winging it, you know? People think doctors are so smart, but we’re just winging it like everybody else. How much do you really know about the world? Really?”

Knock… Rap rap rap rap… Rap knock… Knock……. Rap rap rap… Rap… Rap… Knock knock… Rap… Knock rap rap..... Rap knock……. Rap rap rap… Rap knock knock… Rap… Rap knock rap

rap… Rap knock rap rap… Rap rap… Knock rap… Knock knock rap……. Knock knock knock… Rap rap knock rap……. Knock… Rap rap rap rap… Rap……. Caro winced and placed his hands against his ears.

“Hey, I’m talking to you buddy.” the doctor admonished.

“I’m sorry. It’s just … the knocking … it’s … incessant.”

“You know, one theory I have about this very very very rare disease, is that it’s caused by stress. Have you been under a lot of stress lately?”

“Yes, actually. It’s this knocking you see.”

“Mhmm. Have you been eating healthy?”

“I haven’t eaten at all since this started.” Caro motioned to the eggs benedict, hashbrowns and tea on the tray sitting on his bedside table. The food had grown a hirsute exterior of green mold. “I find it hard to eat when I’m so uncomfortable.”

“Mhmm. Mhmm.”

“On top of that, I’ve been wearing these uncomfortable pants for some time now. They are far too tight, and it hurts quite a bit.”

“Mhmm. Why don’t you just answer it?”

“I-”

“Like… just answer the door already.”

“I cannot walk without my crutches, which are on the mantle over there, out of my reach.”

The doctor looked at the fireplace. There, on the mantle, underneath a poster displaying the muscular system, were the crutches.

“I see.” Doctor Stravinsky rolled his swivel chair over to his desk and dialed a lone button on the phone. “Nurse Ratched?” he covered the receiver and whispered to Caro “That’s her real name!” he cleared his throat and returned his attention to the Nurse, “Can you see what all this knocking business is all about? Pronto. Thank you.”

He hung up and scooted his way back to Caro. “If you want my advice-”

“Yes. I do. Please.”

“I would see a psychiatrist. If stress is really at the root of the problem then they are the only ones who can solve it.” The doctor rose and removed his latex gloves, which he deposited in a biohazard receptacle affixed to the wall. “Now, if you’ll please excuse me.” he ventured down the hall where he tended to his other patients.

“I’m already part dead, anyway.”

Edmond frowned. “Now why would you say a thing like that? Don’t say that.”

“Well my leg is dead, innit?”

“Is it?”

“Well it doesn’t exist anymore. Isn’t that what death is? Not existing? Part of me no longer exists. I’m part dead.”

“What about fingernails and hair and stuff? Are they dead?”

38

“Hmm. I’m not sure if those count, but sure, I guess we’re all dying, all the time, slowly. Gradually losing pieces… maybe life is just the period of time it takes for someone to die.”

“Does it really not exist anymore? Your leg, I mean.”

“I don’t know.”

“What do they do with severed limbs at the hospital?”

“Probably donate them.”

“That can’t be right.”

“Why?”

“Because then they could donate it right back to you. Why give it to someone else?”

Caro thought for a moment. “Maybe someone else needed it more.”

“More than you? I can’t think of anyone who would need a leg more than the person who just had it ripped off of them.”

“Maybe someone of a lower economic status. One of the underprivileged. Someone who could get more out of it.”

“Out of a third leg?”

“No, I mean like someone who also only has one leg, but who needs a second one to support themselves.”

“I don’t think many of us could hold ourselves up with only one leg, not for very long at least.”

“No. I mean support themselves financially. Someone who works on their feet, like a construction worker or a stock person at a grocery store.”

“How would someone lose their leg at a grocery store?”

“Maybe a case of hams fell off a meat truck and crushed him.”

“Has that happened before?”

“It must have happened once. Besides, the point is moot since my leg was torn so that it is mangled beyond use.”

The knocking continued.

“Ze problem,” said Doctor Schwarzenberger, a small Austrian man with round glasses, a grey beard and a smart victorian era suit “zeems to be ztress.”

“Yes.” responded Caro, who thought the man looked rather a lot like Sigmund Freud, or rather like a cliche representation of a psychiatrist. ‘But if he is a real person,’ Caro thought, then I suppose he’s not a cliche representation. He’s just real.’ “I’ve been under a lot of stress lately, with this knocking and all.”

Knock knock rap… Rap knock rap… Knock knock knock… Rap rap knock… Knock rap… Knock rap rap– …Knock… Rap rap rap rap… Rap……. Rap knock rap… Knock knock knock… Knock knock knock… Rap rap knock rap……. Rap knock knock… Rap knock… Rap rap rap……. Rap rap rap… Knock rap knock rap… Rap knock… Rap knock rap… Knock rap Knock rap… Rap… Rap knock rap rap… Knock rap knock knock……. Rap rap rap knock…

“Ze knocking?”

“Yes. It’s been going quite some time.”

“You know, I had a very zimilar problem at mine offize in Vienna. There vas un butcher shop underneath, und all day zey tenderized ze meat. BANG BANG

BANG BANG BANG. All zrough mine zessions.”

“That is a very similar problem.”

“You know vat I did about it?”

“What?”

“Nutzing. Not a zing. I leet it go. It vas beyond mine control. Ze vorld ist much larger than you, young Caro. Zere izn’t much that you, I or anyone can do about zese things. Just accept them und move on.”

“But- … But don’t I have the right to be comfortable in mine own- I mean… my own home?”

“Nutzing is guaranteed to us, Caro. Not even un home. Ve are alone in zis vorld. Und you have to underztand zat zere is nutzing you can experienze, that others have not, and vill not experienze alzo.”

“So I am alone, but not alone in my suffering?”

“Yez. Prezizely. There is zolidarity in zuffering. It ist ze one zing ve share.”

That night, Caro laid in bed, in pain. His body was throbbing from the disease, and the knocking, as usual, would not stop. His mouth particularly dried, he leaned over to his chest of drawers and removed a glass of water that sat atop it. He drank the whole thing and found it did nothing to wet his mouth. The new pants from his cousin Marcus had been chafing his skin for some time, and when he placed his hands on the sores at his waist he cried from the pain.

The night dragged on and he soon found he could no longer move his body at all. He laid there, staring at the ceiling and said to the mysterious knocker:

“Please… please … come in.”

Rap rap… Rap rap rap… Rap rap… Knock rap rap rap… Rap knock rap rap… Rap– Knock… Rap rap rap rap… Rap……. Knock rap knock rap… Knock knock knock… Rap knock rap… Knock rap… Rap rap… Knock rap knock rap… Rap– ……. Rap rap… Knock rap……. Knock… Rap rap rap rap… Rap……. Knock knock rap… Rap knock rap… Knock knock knock… Rap rap knock… Knock rap… Knock rap rap–

“Please … there might not …”

Rap rap rap… Rap rap… Knock rap… Knock rap knock rap… Rap……. Knock… Rap rap rap rap… Rap… Knock rap– ……. Knock… Rap rap… Rap rap rap……. Knock rap knock rap… Rap… Knock rap… Knock… Rap rap knock… Rap knock rap… Rap rap… Rap… Rap rap rap– ……. Rap knock… Knock rap… Knock rap rap…….

“There… there might not be much time…”

Knock rap knock knock… Rap… Knock…Rap rap knock rap… Rap… Rap… Rap knock rap rap… Rap rap rap……. Rap rap rap… Rap rap rap rap… Knock knock knock… Rap knock rap… Knock… Rap… Rap knock rap……. Knock… Rap rap rap rap… Rap knock… Knock rap……. Knock… Rap rap rap

39

rap… Rap……. Knock rap rap… Rap knock… Knock rap knock knock Rap rap……. Rap rap knock rap…

“Please…”

Caro closed his eyes. Rap rap… Rap knock rap… Rap rap rap… Knock……. Rap rap rap… Rap rap knock… Rap knock rap… Knock knock… Rap rap… Rap rap rap… Rap… Knock rap rap……. Knock… Rap rap rap rap… Rap……. Rap rap rap rap… Knock knock knock… Rap knock rap… Rap rap rap… Rap… Rap rap rap……. Rap rap rap rap… Rap… Rap Knock… Knock rap rap… Rap rap rap… Rap Knock knock… Rap… Rap knock rap… Rap……. Knock… Knock knock knock… Rap knock knock… Rap knock… Rap knock rap… Knock rap rap……. Rap… Knock… Rap… Rap knock rap… Knock rap… Rap rap… Knock… Knock rap knock knock–

His corpse had been laid in a casket, which laid on the bed. The people from his life surrounded him. Some of them spoke. The eulogist was Father O’goldstein. He was pleasant. Very pleasant actually. Many calaveras literarias were recited.

Edmond said: “A lot of you don’t know this, but I was not only Caro’s best friend, but I was also his father. I had him when I was very young, 12 years old to be exact. Quite a scandal actually. His mother was my badminton instructor, a woman of 34, who had relations with all her pupils, something for which she remains behind bars to this day, and so regretfully cannot attend these proceedings, but sends her regards.

“In our town the elementary school and the high school were next door to one another, and so when I was a senior in high school and he in first grade, we would walk to and from school together, and we have been best friends ever since. After graduating I took a job on an oil rig to support my son-slash-friend and worked very hard, determined to give him the kind of life I never had. I began pumping oil, climbed the ranks and eventually bought my own oil company, one of the largest in the world, and it was this that funded Caro’s and my matriculation to an Ivy League school, where we were dormmates for four years, upon his graduation. And so we were also college chums.

“I have now lost not only my son but also my best friend, and none of you know how that feels. You think you do, but you can never know another man until you hang dick in his trousers, that’s something I always told my dear son-friend. You just can’t know what someone else is going through, no matter how hard you try.”

When Edmond left the podium and returned to his place beside the mantle, where Caro’s crutches remained, Doctor Stravinsky put a consoling hand on the man’s shoulder and said, solemnly: “Caro is a girl’s name, you know.”

The waitress from the cafe liked Edmond’s speech terribly. Although, she herself would admit she missed a few pieces, distracted as she was thinking about

her own inevitable expiration. In fact, everyone at the funeral was distracted thinking about their own deaths. This is what people think of at funerals. Afterwards they all went to the pub and, in order to cheer themselves up, drank many drinks served by the waitress from the cafe (who was also the waitress at the pub) and told stories about Caro—happy, funny stories about how he was always laying in bed, how he was always annoyed by the knocking, how the knocking never ceased, how the knocker never revealed his or her self, how strange it was. Doctor Schwarzenberger looked at Caro one last time, laying in his casket on his bed, raised a stein and said “To ze boy!” They all repeated “To ze boy!” and drank from their respective beverages in honor of the boy. They all got drunk, but not too drunk, and watched as two gravediggers, under the supervision of an undertaker pushed Caro’s casket, with his body in it, off of his bed and into his grave, which was situated between Caro’s marigolds and his hibiscus (both of which had recovered quite nicely) and adorned by a headstone that listed the years he was born and died. There was also a brief epitaph concerning what kind of person he was and what he did. It also had his full name (at the top).

The knocking stopped.

40

Untitled Yahvi Mahendra

Meet me in your Dreams

Serendipity Stage

42

lunar beast

Sabrina Zhong

Beneath the stainless satin light of moon, a hunter and his hounds wait and watch.

A huntress and her helpers wade and wash— gleaming, splashed with sterling, when he sees her. She seethes, resplendent, white-hot, when he sees, her rage an arrow hissing through the branches.

He whirls, attempts to flee—velvet branches unfurl; steps turn to hoofbeats; he remembers felling deer with trusty dogs. They remember nothing of their master. He is prey and bone.

Nothing remains but guilty blood and bone. The hunt complete, his hounds, uncalled, return.

A single glance the point of no return, beneath the soundless scarlet light of moon.

43

The Start of Something 1

Sophia Abrams

Sophia Abrams

Dark rooms make great resting places making the enigma placing desensitized under my head waiting for the epiphany to light my space. I woke up with a bungalow in my throat. The doors wildly open and shut in every breath.

The ceiling of my room became rain. God was crying over my head He thundered to me his first heartbreak and lighting his true love. God rested in my bungalow.

He created a city of where I was no longer estranged God granted me with enough Culture sharpened a knife for me with American Ethnicity carved black in the handle Gender painted woman on the blade

Epiphany returned with man and man told me to not my knife became not American enough, not black enough, not woman enough

I was damned to who I was damned to what I was damned to am I was damned to are I was damned to I I was damned to you

Misplaced

45 Misplaced

DeOnna Garrison

Solace Brian Huynh

Solace Brian Huynh

Time Grows Apart

Emily Wesoloski

The shade had been an observer for as long as she could remember. She wasn’t a ghost, not really — maybe she couldn’t manifest herself physically, but she didn’t haunt. She watched the world around her, and she mostly kept to herself.

She couldn’t remember anything from before waking up underneath her basswood tree. It was late winter then, and everything had been so cold. She’d watch the evergreens of her forest grow, millimeter by millimeter despite the oppressive snow. She’d reach a translucent hand out towards the deer that would wander past her in her clearing, gusts of wind spooking them away before she could ever touch their silky pelts. It took the snow disappearing for her to finally explore the forest away from the ancient basswood. Once the trees began to bud and the forest woke up, she couldn’t help herself — she had to see it all.