19 minute read

The 7470 Returns to the Valley

Conway Scenic Railroad owner, David Swirk, gives the thumbs up and a smile as he drives the CSRR 7470 on its first run after re-certification, June 29, 2019

Phil Franklin photo

THE STEAM ENGINE THAT COULD ... AND STILL DOES!

Advertisement

By Phil Franklin

The grand era of steam locomotion spanned the century from roughly the 1850s through the late 1950s. It brought major and lasting changes to the United States and Canada. Steam locomotives pulled the trains that helped build our nations, moving people and freight at much faster rates than the horse and wagon or stages coaches. In 1800, Oliver Evans, inventor, engineer, and one of the first to build high-pressure steam engines, said, “The time will come when people will travel in stages moved by steam engines from one city to another, almost as fast as birds, 15 or 20 miles an hour … .” When two steam engines met at Promontory Summit, Utah on May 10, 1869, a ribbon of rails stretched across the United States. Similarly, with the driving of the last spike completing the Canadian transcontinental railway on November 7, 1885, at Craigellachie, British Columbia, Canada, the western regions of our friendly neighbor to the north were opened. The infrastructure was set to bring Mr. Evans’ foretelling to reality. Steam locomotives would soon crisscross our nations and a love affair for these mighty giants was ignited.

While the railroad industry phased out nearly all of the steam engines by the beginning of the 1960s, the fascination and nostalgia for these engines has only grown over the years. Fortunately, as the “steamers” were being taken out of “revenue service” and sold for scrap metal, a number of them were purchased by collectors. Some were mothballed in museums, while others were stored with the hope that someday they would run the rails again. Today, several of these great engines are used in excursion railroads. The massive Union Pacific “Big Boy #4014” engine was just recertified for operation in May 2019. It made a tour of the Midwest, drawing fans of all ages trackside to see this iconic engine. While certainly not as large or powerful as the “Big Boy” or made for long haul service, the Conway Scenic Railroad (CSRR) has a beautifully restored steam engine of its own. It is known simply by the number on its engine plate and the side of its cab, “7470.”

Steam Returns to the Valley

While out of service for an overhaul for the past few years, the 7470 recently made a triumphant return to tracks in the Mt. Washington Valley. On June 29, 2019, the Conway Scenic Railroad reentered the 7470 into the category of “revenue service.” To the applause of several hundred passengers and onlookers, the CSRR 7470 chugged past the North Conway station platform, steam hissing from relief valves, its brass bell clanging, a drift of smoke coming from its stack, and with a blast from its whistle, it announced its return to rails. Dave Swirk, the owner of the Conway Scenic was at the controls with a smile and a thumbs up. The man who was responsible for this engine being a part of the Conway Scenic, Dwight Smith, was trackside. He was delighted to see “his” engine rolling again.

The CSRR 7470 has been the centerpiece of the family of diesel engines and rolling stock (passenger cars) of the Conway Scenic Railroad since 1974. In that year, Smith, opened the Conway Scenic Railroad. The locomotive once known as the Canadian National Railway (CNR) 7470 began riding the rails pulling passenger excursion trains on a short, 11-mile, round-trip ride from the North Conway Station to the Conway station and back. It has been a rail fan highlight ever since.

For the past four years, however, the CSRR 7470 has been absent from the rails of this famous tourist destination. On January 3, 2015, the engine made its last run before being parked in the roundhouse shop for a federally mandated inspection, overhaul, and recertification. And there it sat until October 2018, according to Swirk, with only minor repairs being done to it over those years. In October 2018, the Conway Scenic began a major overhaul of the engine. Specialized tradesmen were engaged to get this engine back in working order and on the rails again for all to enjoy.

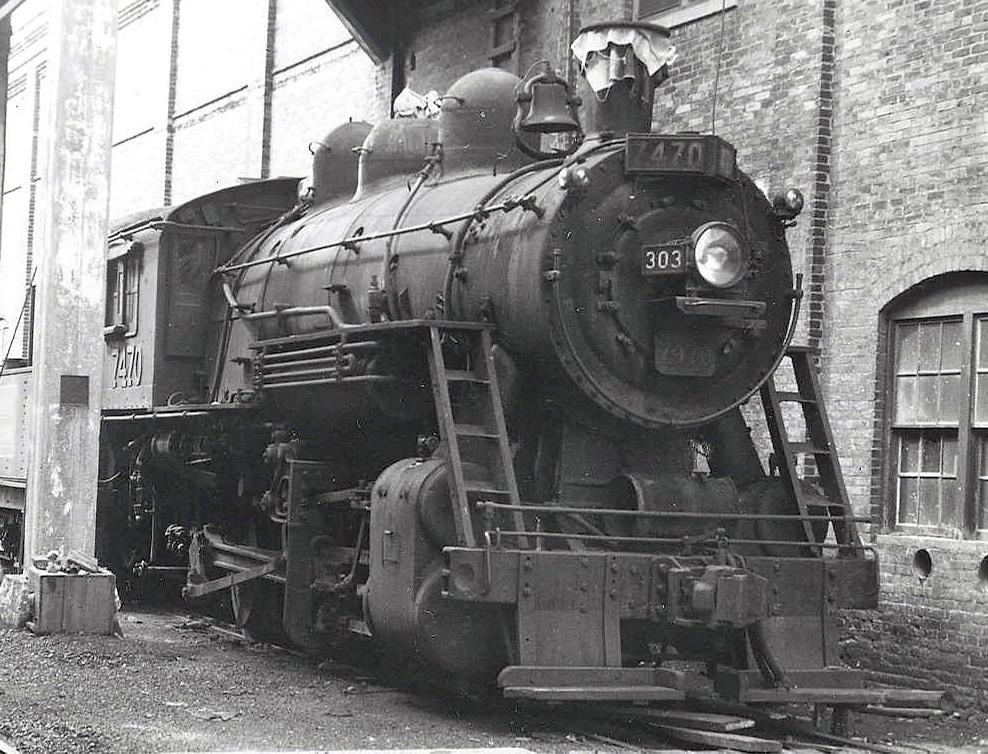

CNR 7470 out of service March 1966 on tracks in Wallaceburg, Ontario, headlight and bell removed.

Photo from Don McQueen collection

The Birth of the 7470

The 7470 was a product of the Canadian railway system. To dig into the 7470’s Canadian history, we connected with Al Lill, chair of the Canadian National Railway Historical Association (CNRRHA). He, along with several of his associates, provided a wealth of early history information for this article on this engine, plus the operation of the Canadian National Railway in the era of steam. We thank them for their support in developing the 7470 story.

Long before the CSRR 7470 became an excursion engine, it was a working engine in the railyards of Southern Ontario and Montreal. This steam engine was built in June 1921 in Canada in the Pointe Sainte Charles shops at Montreal, Quebec. Its boiler was built by the Canadian Locomotive Company of Kingston, Ontario. It was one of 50 small but powerful class “O-18-a, 0-6- 0” steam engines built for the Grand Trunk Railway between 1919 and 1921. It was originally designated as GT 1795 (Grand Trunk 1795). In 1923, the Grand Trunk Railway was consolidated into the Canadian National Railway. At that point, the engine was re-designated as CNR 7470. The 7470 was built to function as a “switcher” or “yard goat” engine.

The main function of a switcher was to “reclassify” trains. To get freight and passenger cars to their proper end destinations, long trains traveling great distances stopped in railyards where they would be disassembled, and the cars reassembled into new trains. This is similar to how major freight services, such as UPS and FedEx, move packages today from originating points to major distribution hubs to local distribution centers and then to your door step. Once a new train was assembled, the larger over-the-rail engines would then take the newly built train to its next location where it would again be reclassified. Switcher engines would also move train cars carrying coal, ice, and industrial supplies to companies within the limits of the railyard. The switchers could not haul long trains over the rails between cities as they were too small and only designed to run at a maximum of 20 miles per hour.

The 7470 toiled in several different railyards throughout its working life. It was transferred from railyard to railyard as service needs of the railway changed across Southern Ontario. While there are no known records of where the 7470 operated from 1921 to 1944, information from our CNRRHA friends has given us a view into the 7470’s assignments in the last half of its service life. Between 1945 and 1959, the 7470 was assigned to railyards in Toronto, Windsor, Lindsay, Midland Ontario, Stratford, London, Sarnia, Chatham, Ontario, as well as Turcot and Montreal, Quebec. Precise dates of service are not exact, as there is no one journal that recorded the travels of any of these engines. Locations of the 7470 are only known through a manual search in Canadian National Railway records. And, since documents could be missing, we likely have an incomplete record of assignments for the engine.

Throughout the service life of the CNR 7470, it, like all other steam engines, went in for minor repairs and maintenance or periodic major service overhauls. Normal maintenance work or minor repairs could be handled at any rail terminal. Large overhaul operations were conducted in the rail shops in Stratford or Pointe Sainte Charles, Ontario. Overhaul times were determined by the miles traveled by an engine and the measurement of the drive wheels, which would wear down over time. The CNR 7470 received its last major overhaul while working for the Canadian National in September 1955 at the Stratford facility. Overhaul work was done in union run shops and involved a number of tradesmen, including boilermakers, pipefitters, electricians, painters, welders, and carpenters. According to Lill, the length of time involved in the maintenance and repair of this engine could vary from hours to days. Overhauls could last weeks or months, depending on the type of work needed.

While in Canadian National operation, the 7470 and all other switchers needed several crew members. They included the engineer and fireman in the cab of the engine. There were at least two switchmen who rode on the front of the engine or running boards on the tender. They coupled and uncoupled cars for reclassification, threw the appropriate switches in the yard to get the 7470 to its proper track locations, and set or released brakes on the cars. There was also a man on the ground directing the movement of the reclassified cars. This was hard, sooty, and dangerous work for all of the people involved. With each new location for this engine, new crews bid for the jobs on the engine as they did throughout the railway operation. Senior men in positions could bump junior men to get better jobs, certain positions were “protected,” and rebidding occurred each April and October.

CNR 7470 renumbered at 303 at Wallaceburg, Ontario sugar refinery, 1961

Photo from Don McQueen collection

The 7470 Ends Canadian National Service

As we approached the end of the 1950s, the Canadian National Railway was replacing the labor- and maintenance-intensive steamers with new diesel engines. Of the 50 switchers in the class with the 7470, all were sold for scrap metal—with the exception of three engines. According to information from Lill, the “CNR 7470 and sister 7456 were both sold to the Canada and Dominion Sugar Company” (a beet sugar refinery) on September 16, 1959. While hauling for the sugar refinery, it sported the number “303” on its headlight. The 303 or 7470 was first assigned to the Chatham, Ontario refinery and then transferred to the Wallaceburg facility by 1961. This was the first of a short string of new owners of this engine. The sister engine, 7456, was eventually sold to Montcalm Community College, where it is located today, mothballed in the college’s Montcalm Heritage Village in Sidney, MI. The third engine to survive the Canadian National purge of the steam engines was sold to International Harvester in 1958. They scrapped the engine in 1961. This makes the 7470 the only operating steam engine of that class of 50 engines.

In May 1963, the 7470 was sold to the Ontario Science Centre project after the sugar refinery was shut down. Tracing the lineage of this engine to the science center, we learned that they actually have no official record of the engine being with them—but there’s a good explanation for this. At the time of the sale, the science center was just being formed, so the word “project” looms large in this part of the 7470’s life. Our contact at the science center told us that in 1963, artifacts and exhibits for the center were being considered for the museum’s collection, hence, the project of starting a museum. Apparently, a decision was made to exclude the 7470 from the museum’s collection, so it never made it to the official collection list for the museum.

In 1965, the 7470 was sold to a man named Charles Weber. The engine remained unprotected at the Wallaceburg location for a number of years while it was owned by the science center project and Weber. Its headlight and bell were removed and presumably stored in the cab for safe keeping, according to Don McQueen of the CNRRHA. McQueen also said that local folklore has it that “ivory hunters” stole the headlight and bell, but this has never been substantiated. At an unknown date, the 7470 was sold to a rail car collector named Fred Stock of Reese, MI. By this point, the engine was moved to the CNR railyard in Sarnia, Ontario for storage. The engine was now about to undergo another change in ownership that would bring new life back to this engine.

David Swirk, owner of the Conway Scenic Railroad, stands with Dwight Smith, the visionary founder of the Conway Scenic, August 4, 2019

Phil Franklin photo

A view across the gauges, controls, and levers in the cab of the CSRR 7470 with Conway Scenic Railroad owner, David Swirk, at the controls.

Phil Franklin photo

Conway Scenic workers apply uniform heat to a piece of the CSRR 7470 fire box to refit it on the engine as a part of the renovation process for the engine.

Photo courtesy of Conway Scenic Railroad

Dwight Smith, the 7470 and the Conway Scenic Railroad

With the 7470 now in his ownership, Fred Stock may have considered moving the 7470 to his railyard in Reese, MI, according to Smith in his March 2007 article in Railroad Model Craftsman magazine. Thinking better of this, Stock placed a simple advertisement in Trains magazine: “0-6-0 Steam Locomotive for sale” (0-6-0 refers to the wheel configuration of the engine). That advertisement caught Smith’s eye at his home in Portland, ME. After some fast negotiation, in April 1968, Stock sold the CNR 7470 to Smith. The story of the history of the 7470 now turns to Smith and his vision to open a tourist excursion railroad in North Conway, NH. Today, we know that railroad as the Conway Scenic Railroad. And, forever, the 7470 and CSRR will be linked.

Before Smith was purchasing the 7470, he was working with two new business partners, Bill Levy and Carroll Reed, both North Conway business owners, to open the Conway Scenic Railroad. In a March 2019 interview with Smith, he told the story of how the Conway Scenic came to be. The partnership of Levy, Reed, and Smith started in February 1968 when Smith arrived for a day on a Boston & Maine (B&M) Snow Train excursion to North Conway. This was one of the last “Snow Trains” to run on the B&M tracks through North Conway. A 1988 Conway Scenic Railroad booklet written by D. W. Swift, states that this train was chartered by the Massachusetts Bay Railroad Enthusiasts, Inc., a Boston-based rail fan club. Smith, a long-time railroad enthusiast and employee of the B&M Railroad, upon arrival at the rundown North Conway station, saw this location as the perfect spot for a tourist railroad. He spent the day talking with local shop owners and eventually made the connection with Levy and Reed. They owned the station and associated railroad builds, but didn’t own the track. In a subsequent 30-minute telephone call from his home in Portland, Smith “sold” Reed and Levy on the idea of opening a tourist railroad— and so, the Conway Scenic Railroad was born.

Of course, a railroad needs locomotives, train cars, and track; they had none of them. The legal battle to get the track rights from the B&M Railroad took six years. The purchase of the first CSRR engine took place rather quickly, as the 7470 was bought shortly after the idea for the railroad was struck. But the 7470 was just a non-working, rusted engine sitting in Sarnia, Ontario. Passenger railcars needed to be purchased, renovated, and readied for excursions. Smith said there were many doubters, including his wife, for a while. What the Conway Scenic had going for it, though, was the vision and tenaciousness of Dwight Smith.

And so, we get back to the purchase of the 7470. Knowing he needed a locomotive for his railroad and believing that a steam engine would be best, Smith purchased the rusted 7470 in Sarnia, Ontario, Canada for $7,000. He quipped that he didn’t even tell his wife about the purchase until after it was completed. When he told her, she first thought he bought another small HO engine for his personal model railroad display, not a towering, non-working, rusted hulk. Smith informed her that this one weighs 150 tons! She eventually started speaking to him again. Moving the 7470 to North Conway was a feat in itself. The locomotive was pulled over the rails by another engine. The cost of moving the engine needed to be managed. Freight costs from Canada to the United States were much higher than freight costs of moving within the United States. So, the first move of the 7470 was simply from Sarnia across the St. Clair River to Port Huron, MI. Now within the United States, the second step was to have the engine “rebilled” to Portland, ME at a cheaper shipping rate. The trip to Maine would, ironically, go back through Sarnia and travel through Canada where it would eventually cross back into the United States and arrive in Portland, ME. Because the 7470 was inoperable, the towing operation could only go at a top speed of 15 miles per hour. Bearings on the engine needed to be greased with each overnight stop as the automatic lubrication process was not working on the 7470. Smith had different crews available to service the engine as it was being towed, and he joined in that journey. He said that people would come to see the engine as it passed by and stopped for overnights in train stations. One group of Canadian children came to see the engine, left for home, and then returned to provide Smith with lunch. The 10-day trip ended on Columbus Day weekend 1968 at the Rigby Yard of the Portland Terminal Company on a section of track rented by Smith. When the engine reached Portland, his wife saw it for the first time. She christened it by breaking a bottle of Champagne on the front coupler.

CSRR 7470 Technical Trivia

The 7470 is a Class O-18-a, 0-6-0 engine. In layman’s terms, the class of the engine, O-18-a, designates it as a switcher engine that can haul heavier loads as compared to other switchers.

The 0-6-0 refers to the wheel assemblies for the engine. This type of nomenclature is used for all locomotives.

Breaking the 0-6-0 (zero-six-zero) down

The first “0” refers to the most forward set of wheels or “truck” on the train engine. Larger locomotives with twowheel trucks have a “2” as their first designation number, some have four forward wheels, hence a “4” in the first number. These wheels help larger engines navigate the curves on the rails.

The second number, “6,” represents the number of large drive wheels. The 7470 has six drive wheels. Larger engines can have eight drive wheels, for example, so their second number would be an “8.”

The last “0” is the number of wheels in the rear truck supporting the fire box. In the 7470, there are no wheels beneath the firebox. In larger engines that have two or four rear truck wheels, this number would be a “2” or “4.”

The other steam engine in the Conway Scenic Railroad railyard is the (currently inoperable) 501. This is referred to as a “2-8-0” because it has two front truck steering wheels, eight drive wheels, and no wheels under the firebox.

Facts and figures about the CSRR 7470

• 62’ 8” long (with its tender)

• Weighs 304,000 pounds (with its tender)

• Carries 5,500 gallons of water in its boiler

• Has four 22” x 26” cylinders that provide the power to drive the train, and the engine rides on 51” drive wheels

• Maximum speed is 20 mph

Its original “tractive effort” (weight it could pull or push) was 36,703 pounds, giving it a “haulage rating” of 37%. Today, that rating is down to 33% because of the age of the engine. While still a formidable engine, it is no match for the much larger engines that pulled the long trains between destinations. But then, it was never designed for the long-haul duty. As a switcher, it could hold its own, handling as many as 10 or 11 cars at a time.

The 7470 stayed in Portland until 1971, when it was moved to North Conway. It was here that Smith found some experienced boiler workers, mostly school teachers on summer vacation, who could do a professional job getting the engine

back on the tracks in operable condition. Smith’s words best describe the rebirth of the, now, CSRR 7470 in his March 2007 article in Railroad Model Craftsman magazine. He wrote:

The first steam up took place on August 3, 1974, and we ran our first revenue train on August 4, 1974. From then until the year 2002 the 7470 faithfully carried trainloads of tourists on an eleven-mile, round-trip excursion. In 2002, the 7470 was shut down for several years while it underwent restoration to comply with new FRA (Federal Railroad Administration) standards. In August 2006, the 7470 returned to regular service, to the delight of passengers, crew, and visiting railfans.

In a brief conversation with Gordon Lang of Jackson, NH on August 4, 2019, he proudly said that he was the man who first fired up the locomotive engine on August 3, 1974. He remarked that they needed a fireman for the engine. He was friends with the engineer and was a Jackson, NH fireman, so he “knew how to put out fires; the engineer taught him how to start a fire.” He said that he was replaced by a “real” locomotive fireman on the August 4th excursion.

When the CSRR 7470 first came into service with the Conway Scenic Railroad, it carried the number “47.” Mr. Smith confessed that he changed the number because it was shorter to write than “7470.” However, he said that many people wanted it changed, so in 1989 he restored its Canadian National number, “7470.” To this day, however, some people still remember the engine as #47. The engine also made a brief film appearance in the 1972 film, A Separate Peace. In that film, it was lettered as “Boston and Maine 47.”

Another Restoration and Rebirth On January 3, 2015, the CSRR 7470 made its last run for a long while, closing its 2014 season with the special “Steam in the Snow” train. It was on that date when the engine was again put in the North Conway station roundhouse shop for restoration, as required by the Federal Railroad Administration. The engine would again need to be recertified by the FRA before it could be operated again. For the next four years, something was missing in the summers and falls in the Mt. Washington Valley. The sound of the steam train was temporarily silenced. In an interview with the new owner of the Conway Scenic Railroad, David Swirk, he said that from 2015 to October 2018, little work was done on the CSRR 7470. In October 2018, however, he led the effort to get this engine recertified for limited use and back on the rails for everyone to enjoy. According to Swirk, this effort required “many” hours of effort by skilled professionals and was “not cheap.” The primary contractor for the overhaul of the engine was Brian Fanslau of Maine Locomotive & Machine Works of Alna, Maine.

The restoration process required that every part on the CSRR 7470 needed to be inspected. This meant disassembling the entire engine so all that was left was the frame and wheels. Proper corrective, cleaning, or replacement actions were taken for each part of the engine and tender. This involved all of the engine pumps, compressions, the entire boiler, fire box, and any other working parts. If new parts were needed, they were either made at the North Conway shop or forged in a local foundry. There are no off-theshelf parts for this engine because of its one-of-a kind status.

During the restoration, the boiler required the most attention. Swirk commented that all of the small tubes were removed from the boiler. A special process known as “needle scaling” was done to get the boiler metal cleaned of rust. This took many hours of difficult work by a specialized boilermaker. Aside from the boiler, all of the lubrication systems in the engine need to be inspected and rebuilt. All gauges needed to be recalibrated and valves checked for proper operation. After the engine was reassembled, an extensive testing process was undertaken to ensure that everything was operating correctly with all of the parts in the engine working in unison. Safety is paramount for this engine to be allowed on the tracks.

The testing process for the engine began long before the engine left the shop, with the major test being a “hydro test.” In this test, the boiler is filled with water and placed under pressure to identify any leaks in the engine. Track testing of the engine was done to ensure that everything was operating as expected. A major focus of this test is on the lubrication systems of the engine. There are five different lubrication systems in the engine, and all are critical to its smooth operation. One of the biggest issues with any moving parts is the wear caused by the rubbing of metal on metal. If any one of these lubrication systems fails, it could mean the seizing of that part of the engine. The track testing of the engine took about one month, with many repeated track runs. Once all the tests were completed and the engine was recertified for limited use over the next 15 years, she had another “maiden voyage” on June 29, 2019.

A Reflection on a Long Life

Swirk has pledged that the Conway Scenic Railroad will preserve the CSRR 7470 as a piece of history for future generations. He added that while it is expensive to keep the CSRR 7470 alive and running, he sees it as a price to pay for the preservation of history in the Mt. Washington Valley. And with that philosophy, the CSRR 7470 is in a good home with an ever-watchful caretaker. Mindful of the engine’s past, on August 4, 2019, the 45th anniversary of its first excursion run with the Conway Scenic Railroad, a dedication ceremony was held. With Swirk at the microphone, the announcement was made that the CSRR 7470 is now officially dedicated to Dwight Smith. Smith’s name is permanently placed on the cab below the engine’s number. Swirk referred to Smith as the “Walt Disney of the Conway Scenic Railroad.” At the dedication ceremony, Smith remarked, “The engine was built in 1921 and I was born in 1925—and we’re both still running!”

At 98 years old, this steam engine, like the other remaining operational steamers, stirs a nostalgic emotion in many people and a sense of wonderment in others. It relives memories and builds new ones. It escaped the trip to the scrap yard and became the centerpiece of the Conway Scenic Railroad. Just like The Little Engine That Could, the CSRR 7470 remains vigilant in its mission to the delight of the young and young at heart.

OPERATING A STEAM ENGINE & THE ENVIRONMENT

The ypical mental image conjured up when a person hears of a steam engine is a black-smoke-belching metal giant with steam rushing out of its relief valves. That is a fair image. But what of the environmental concerns with running a steam engine? People can say that these engines contribute to air pollution and the release of greenhouse gasses because of their source of energy: coal (or, in rare cases today, wood or oil). They can also say that these engines use precious water in the process of powering the engine. To address this concern, we first found publication EPA-420-R-98-101, Appendix L from the United State Environmental Protection Agency. This states, “Locomotives originally manufactured prior to 1973 are excluded from regulations … . ” Steam locomotives used in excursion railroads are in limited use, therefore, their carbon footprint is relatively low. The EPA document concludes with the following statement, “Since the benefits from emission control could be low, expressed as an annual mass of emissions, and the cost of controls high, exclusion of these locomotives from regulation appears appropriate.” The concern over the water is summed up by saying that the water expelled from the engine in the form of steam condenses into clean water vapor, which is then absorbed into the standard cycle of water evaporation. Next, we discussed this topic with Swirk, owner of the Conway Scenic Railroad (CSRR). He said that the railroad is very concerned about the environment. He agrees with the EPA assessment that the CSRR 7470 is used infrequently, and therefore, is not a major polluter in the Valley. To add to this, he said that at the Conway Scenic Railroad, they blend a mix of 50% anthracite coal and 50% bituminous coal. The bituminous coal makes the thick clouds of smoke coming from a steam engine. While the CSRR 7470 is designed to run on bituminous coal, they prefer to run with this blend to reduce coal emissions. When you see the CSRR 7470, notice that the column of smoke coming from its stack is far less than one would expect. Yes, you still can experience the coal cinders coming from the stack, but CSRR is making a concerted conscious effort to reduce pollutants coming from its steam engine and preserve our mountain environment.