2 minute read

HISTORICAL SNIPPET

Radar's early days at Wits

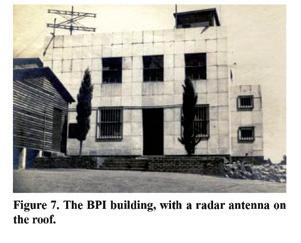

The first radar set in South Africa was born on the Wits campus within the three months of the outbreak World War II under the direction of Professor Basil Schonland (DSc honoris causa 1957), who was the director of the Bernard Price Institute of Geophysical (BPI).

Schonland assembled his design team from engineers who were specialists in radio engineering: Guerino ”Boz“ Bozzoli (BSc Eng 1934, DSc Eng honoris causa 1948, LLD honoris causa 1978) at Wits, Noel Roberts at the University of Cape Town and Eric Phillips in Natal. They were joined by the BPI’s physicist Dr Philip Gane.

On 16 December 1939 Schonland and Bozzoli went to Wits to make some last-minute adjustments to the equipment and while there they carried out a trial run of the elementary apparatus. Two previous tests of the radar had failed to produce the telltale “blips” on the cathode ray tube of the display. In the first they had used a helium-filled balloon to suspend a mesh of copper wires as it floated skywards from a point a few kilometres from the campus. But no radar echoes were seen.

Then Schonland arranged for a flight by a South African Air Force aircraft whose pilot had been instructed as to the course he had to fly. However, on the appointed day, he deviated from this carefully planned route and, instead, chose to fly over the house of his girlfriend in Roodepoort. Unsurprisingly no blips were seen.

Then Schonland arranged for a flight by a South African Air Force aircraft whose pilot had been instructed as to the course he had to fly. However, on the appointed day, he deviated from this carefully planned route and, instead, chose to fly over the house of his girlfriend in Roodepoort. Unsurprisingly no blips were seen.

Bozzoli had erected the transmitter in a top-floor office of the Central Block. And above, on its roof, was the transmitting antenna. The communication between them went via the university’s telephone exchange. Since radar antennas are designed to be directional so as to be able to determine the direction of a reflecting object — the target in the ultimate application — they agreed over the telephone in which direction to point their respective antennas.

This involved a fair amount of stair-climbing and physical exertion. As they rotated their antennas in rough synchronism from north to west Schonland suddenly observed a signal on the display. He shouted to Bozzoli and so they carefully reversed the headings of the antennas and slowly brought them back to that previous position. Sure enough there was the echo. Both men now met on the roof of the BPI and peered in a north-westerly direction from where the reflected signal appeared to have come. And there, about 10km away, was Northcliff Hill and on top of it was its concrete and steel water-tower. Further careful variations of the antennas’ headings confirmed, without a doubt, that they were indeed seeing a signal that had been reflected from what was initially thought to have been the water-tower but which, given the wavelength of the radar, was more likely Northcliff Hill itself.

It was a remarkable day, considering the total lack of familiarity about radar that any of Schonland’s team had had a mere few months before. They had proved by way of a convincing experiment that their equipment did indeed work and it had taken them just three months to get there.

Source: Brian Austin

(SA Military History Society Journal and the Heritage Portal)