3 minute read

Research bytes

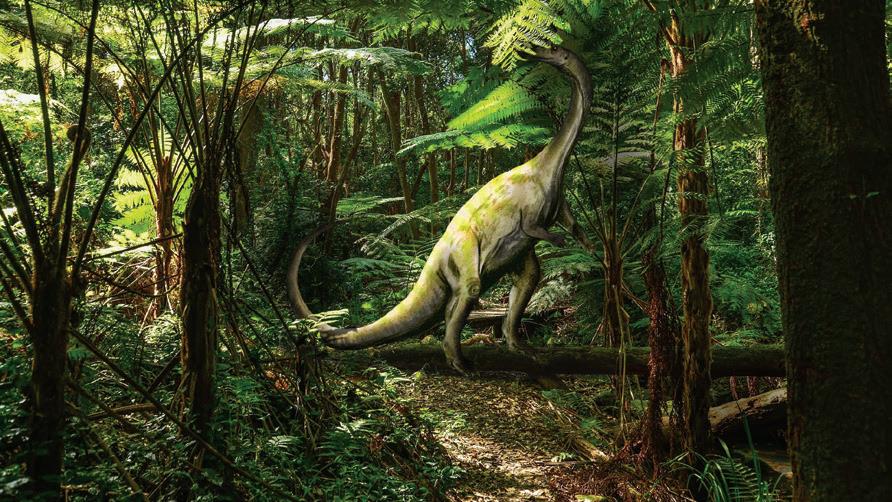

A small bone with big implications

Dr Kimberley Chapelle (BSc 2013, BSc Hon 2014, PhD 2019) is the lead author of an analysis of a single arm bone of a species that lived about 195 million years ago. The original fossil bone was discovered in an area known as the Massospondylus Assemblage Zone in the Karoo Basin in 1978. It was assumed, because of its small size, that the bone belonged to a young Massospondylus.

But Chapelle’s study, published in the journal Royal Society Open Science, shows the specimen was fully grown weighing around 75kg based on bone tissues studies. While there isn't enough evidence to name a new species yet, the fossil suggests that the ancestors of the sauropods and their close relatives, known as the sauropodomorphs, were more diverse than realised. This finding unlocks further research opportunities.

“Until now, we didn't know that early sauropodomorphs could get this small, so the smallest skeletons were assumed to be babies. We can now reassess these skeletons discovered in southern Africa and hopefully find a more complete individual from which we can name a new species,” she says.

The bone's structure suggests the dinosaur was fully grown at the time of its death

Sources: Royal Society Open Science, Genus Africa

Tackle the risk

“If there’s a potential to be involved in a tackle or to be hit there’s the risk of injury,” says Professor Jon Patricios (MBBCh 1999), director of the Wits Institute for Sports Health who co-led the latest international consensus statement on concussion, published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine. The implications were visible in protocols adopted by World Rugby during the 2023 Rugby World Cup. “Safety awareness is higher than it’s ever been, and our protocols are evidence-based and more robust,” he says.

Sources: The Conversation, Wits News

Discovery rocks!

Two Wits geologists Professor Roger Gibson and Professor Lew Ashwal confirmed the “rocks” found by a member of the public, Gideon Lombaard, in the Northern Cape, years apart, were indeed meteorites. “Once we were able to examine the fragments, using a range of petrological and geochemical techniques, we were able to not only confirm that they were meteorites, but also show that the two were distinctly different, despite being found only one kilometre apart,” says Gibson. He says there are currently over 72 000 documented meteorites that have been collected across the world, weighing approximately 700 tonnes, but the entire meteorite collection of the world could fit into a cube with edges of only 6m.

Source: Wits News