14 minute read

Introduction

FRANK NELSON WILCOX: DEAN OF CLEVELAND SCHOOL PAINTERS

This exhibition of watercolors by Frank Nelson Wilcox (1887-1964) provides an opportunity to view fresh, perfectly preserved examples of an array of remarkable work by one of the most highly regarded watercolorists of his generation. A notable feature of the Cleveland School is the excellence of work produced in watercolor, by figures such as Charles Burchfield, William Sommer, Henry Keller, Paul Travis, Viktor Schreckengost and others. Frank Wilcox, who like Burchfield was a protégé of the charismatic teacher Henry Keller, fits into this pattern. While he produced some excellent specimens in oil, watercolor dominates his oeuvre.

Advertisement

In his lifetime, Wilcox was celebrated not only for the excellence of his work, which often won national prizes, but for the speed and easy confidence with which he could produce a watercolor on the spot. He always used simple tools—just three paint brushes, and a chair for an easel, with the watercolor block propped up at a slight angle. Perhaps what’s most remarkable about Wilcox’s work was his grasp of weather and atmosphere in the composition as a whole. His paintings never look as though they were pieced together inch-by-inch but grasp the scene as a totality, with all its complex variations of color and light. As he once wrote of the watercolor medium:

“Many instructive books on watercolor have specific rules for painting objects and effects. The chief difficulty in following these is that they seldom allow for varying distance and are planned as if for stilllife painting. Owing to all its qualities, the medium requires actually more free exercise than others to acquaint the worker with all its possibilities.”

Wilcox was born and grew up in Cleveland, but his family also owned a farm in Brecksville, where he experienced simple rural life of the sort that later became the subject of many of his watercolors. He came of age in a period when magazines and newspapers were expanding rapidly, and journalism and illustration were quickly developing into remunerative fields. His father, who was a prominent lawyer, also wrote poetry and had many friends who were writers or illustrators for the Cleveland newspapers. As a consequence, he strongly encouraged his son’s artistic interests. After graduating from Central High School, where he illustrated the High School Yearbook, Wilcox went on to the Cleveland School of Art, where studied from 1906 to 1910, chiefly with Frederick Gottwald and Henry Keller. Some of his student work is included in this exhibition, including a striking watercolor of the gaunt model Antonio Corsi, who also posed in this period for the famous portraitist John Singer Sargent.

Wilcox went on to spend the better part of two years in Paris, where, untypically for a young artist, he did not enroll in regular classes or a school, but worked on his own. However, he would sometimes drop by Colarossi’s in the evening to sketch the model or the other students at their easels. A diligent worker, he made sketches and watercolors every day, producing well over one hundred in the course of his stay. As a group these works provide an amazing record of the life of Paris and its environs in the final years of La Belle Époque, when Paris was the world’s unquestioned artistic center: barges on the Seine; figures strolling in the parks and on the streets; the laundries and mattress stuffers along the Seine; the flower sellers; the horses and carts which hauled dirt, and trash, and cargo for the river boats; the monumental vistas of the Invalides and Notre Dame.

Part of the discipline of Wilcox’s approach is that he did not fuss or belabor what he did, but worked directly and relatively quickly. His pencil under-drawing in these watercolors is wonderfully accurate without ever becoming stiff; his application of watercolor delicate and suggestive. On his return, to his chagrin and surprise, his old teacher Henry Keller, who had become an advocate of new theories of brilliant, Post-Impressionist color, was severely critical of what he had done, viewing it as oldfashioned. But when Wilcox staged an exhibition of the works at the Taylor Galleries they sold well and were praised in the newspapers. It seems to have been largely on the basis of this success that he was hired as an instructor at the Cleveland School of Art, where he would remain as a teacher for an unbroken stint of 44 years.

By all accounts, Wilcox was an extraordinary teacher. Over the course of his career he taught design, figure drawing, anatomy, illustration, and landscape, as well as etching, lithography, and other techniques of printmaking. Each subject he taught he studied intensively, often devoting his summers to self-instruction, and developing a range of arcane knowledge about such subjects as weather, archaeology, botany, zoology, and kindred subjects. His notion was that to make a good painting, you needed a scientist’s grasp of what you were looking at. To get a better grasp of anatomy he constructed a jointed manikin with rubber bands to play the role of muscles; to

teach landscape composition, he developed a diorama in a box with peep-holes, with dials to move objects around and to control the lighting. He developed highly creative classroom exercises, such as frying eggs to get students to closely observe the freshness of the eggs and the effect of different degrees of heat; or sending students downtown to study a store window and then return to the school and draw it from memory. Despite his erudition, however, Wilcox’s work was never finicky. He drew and painted with bold slashing strokes.

The politics of the Cleveland School of Art in this period revolved around the rivalry between Frederic Gottwald, in the conservative camp, and Henry Keller in the modern one. Gottwald dominated the painting department, whereas Keller, who had worked for several years designing posters in the commercial world, was brought in to teach industrial design. A curious consequence of this split was that most of the students in the school who went on to produce art of national importance, such as Charles Burchfield and Viktor Schreckengost, majored in industrial design rather than painting. In addition, for the most part they learned to work in watercolor rather than oil, since watercolor was the favored medium for producing illustrations and poster designs. Burchfield, for example, produced only two or three oil paintings over the entire course of his career. Not surprisingly, watercolor became Wilcox’s chosen medium of expression.

Significantly also, in this period, following the lead set by figures like Winslow Homer and John Singer Sargent, watercolor was gaining stature in progressive circles as a major medium of expression. In the work of members of the Stieglitz group, such as John Marin, its unique freshness and spontaneity were viewed as qualities at the heart of American identity. At the time he took up his teaching job, Wilcox married a fellow student, Florence Bard, but this did not interfere with his enormous appetite for work, including sessions at Henry Keller’s summer school in Berlin Heights, where he formed a warm relationship with Keller. As Wilcox later recalled:

“Our honeymoon was spent in a tent on a hill with a sweeping view which Keller had recommended. We never knew just when he would appear on his bicycle to ask me to go etching but Florence had no objections with all the girls in the summer class to talk to… We cycled to every little lake port, forge and sawmill in the region and studied the eroded willow clad banks of the Huron. Once he even dragged me out from supper in the tent lest I miss what he called a ‘Jongkind sky’ and it became one of my best plates.”

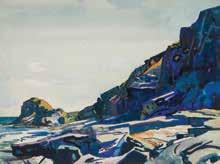

The Paris watercolors set the stage for some of the most remarkable paintings of Wilcox’s career, a group of studies of the coast of Maine produced in a series of summer visits. This show includes some masterful examples, such as a view of the Shore of White Island in Maine, 1923, or a view of the surf on Monhegan, titled “Washer Woman”. Keller’s criticism, while Wilcox surely resented it, clearly had an impact, and gives these works a modern feeling despite the academic accuracy of Wilcox’s drawing. They exhibit fascinating mosaics of rich color patterns. One of their hallmarks is the manner in which shadows are rendered with an indigo which is almost startling in its assertive resonance, in part because most of these works are remarkably unfaded, having been stored for years out of the sunlight. The dappled effect of some of these paintings, such as View Towards Christmas Cove, even brings to mind the work of contemporary Maine landscape painters, such as Neill Welliver.

Shore of White Island, Maine

c. 1923 pg. 108

“Washer Woman” Monhegan Island, Maine

c. 1923 pg. 109

View Towards Christmas Cove, Maine

c. 1923 pg. 106

In 1929 Wilcox’s friend, Alfred Mewitt, who had visited the Gaspé Peninsula, urged Wilcox to go there the next summer on a sketching trip, and Wilcox took him up on the suggestion. He returned for three more years, and the harsh, dramatic landscape, with its rocky headlands, inspired some of his best work, which is similar to his renderings of the Maine coast, but even more dramatic. As he later recalled: “At that time, the region was practically unknown to tourists, and one felt the full spirit of its northern isolation, its wildness, and a quaintness of human existence so dominated by the force of the elements. There were wide horizons, portentous cloud and fogs, and the looming rocks and headlands. All these things fitted my color sense and watercolor technique.”

The landscape particularly lent itself to an effect of which Wilcox was a master: that of contrasting clean, crisp outlines with wet areas, where he let the wet pigment blur edges and run slightly down the sheet, to create the effect of mist or fog. For Wilcox was a master at creating a range of variations of a blurred edge with seemingly simple means. In an unpublished book on watercolor technique, for example, he noted:

“Assuming three conditions of paper—dry, damp, and wet—a single touch will develop as many qualities of edge as the pigment is thin, medium, or thick. Considering this, at least nine perceptible qualities may be created. Another distinct quality of touch is found in the ‘dry-brush’ effect created by briskly sweeping the paper when dry with a color also approaching dryness. This creates a crayonlike texture.”

Careful study of Wilcox’s watercolors will reveal all nine of the blurred edges described, as well as the dry-brush technique.

On his second trip to the region, Wilcox encountered the photographer Paul Strand and his wife, who admired the way Wilcox started his watercolors, which reminded them of Marin, but did not approve of applying greater finish. Wilcox later deprecated their “cultist point of view” and commented that their presence “spoiled the place for me to some degree.” Nonetheless, their comment points towards a sort of underlying modernism in Wilcox’s work, a directness and spontaneity which fills these works with life. After his return to Cleveland, Wilcox showed these works to William Milliken, the Director of the Cleveland Museum of Art, who was wildly enthusiastic, insisted on including them in The May Show, and acquired one for the museum. Sometimes Wilcox worked up to creating a major watercolor by making smaller studies, but significantly, he never lost a quality of freshness in the final statement. Indeed, he commonly dispensed with underlying pencil drawing in the final piece, and worked directly with brush on paper.

Fortuitously, Cleveland provided a wonderfully supportive community for work in watercolor. Frederic Allen Whiting, the first director of the Cleveland Museum of Art, began his career as Director of the Society for Arts and Crafts in Boston, and was an ardent proponent of the Arts and Crafts movement, and of the importance of not only showing the work of dead artists, but of maintaining a vibrant living artistic culture which would bring art into daily life. On his initiative, in 1919, the Cleveland Museum of Art staged its first Annual Exposition of Cleveland Artists and Craftsmen, which soon became popularly known as The May Show, and was staged annually until 1958. It started to change format and be staged less regularly, finally coming to an official end in 1993. For much of its early history, it was curated by William Milliken, who came to the museum as Curator of Decorative Arts in 1919, became Curator of Painting in 1925, and served as director from 1930 to 1958. The show was devoted entirely to local and regional artists, and offered about thirty prizes in different areas, including watercolor painting, which were bestowed by a jury of nationally distinguished artists who came to Cleveland to judge the work. The show quickly became the most popular exhibition each year at the museum, and greatly fostered patronage of work by local artists. Wilcox became a regular prize winner in the watercolor category, and at the height of his career, also regularly contributed to national watercolor exhibitions in New York and Chicago.

This moment of artistic acclaim, however, did not last long. For some time Wilcox had been dismayed by the eccentricities of ultra-modern art. As the 1930s progressed, he became increasingly interested in looking backward into time, which was no doubt encouraged by the Regionalist movement of that decade, and encouraged realistic renderings of the American scene. A major marker of this shift was Wilcox’s book on Ohio Indian Trails, which he illustrated with black-and-white ink drawings similar in effect to woodcuts, and became a best-seller. In it he traced the course of ancient trails, many of them converted into modern highways. He went on to spend years working on a similar book on Ohio canals, which was published only after his death.

Photograph of Wilcox painting, May 1958

What fascinated him was that these canals, which had once been on the forefront of transportation and new technology were now largely abandoned and overgrown. As he commented, “These towpaths became as romantic to me as a dim Indian trail, for they recalled a way of life hectic in its own day, but far less so than this day of high-speed travel over roads which have obliterated the original levels, and span former river fords.”

Increasingly, Wilcox’s paintings became records of nostalgia, many of them images based on the scenes he had witnessed in rural Brecksville as a child, when the life and manners were still essentially those of the American frontier: scenes of ploughing, cutting hay, sawing wood, forging horseshoes, and beekeeping, as well as of relatives gathered in their best clothes for the annual family reunion. Many of these scenes, such as On the Back Porch, Brecksville, have some of the same sober honesty one finds in the contemporary work of American scene painters such as Clarence Carter and Grant Wood. During this period he fell out with William Milliken at the Cleveland Museum of Art, in part because he assumed the presidency of The Cleveland Society of Artists, a conservative group formed in opposition to Keller and modernist tendencies. While he continued to exhibit in The May Show, Wilcox’s last prize there was a “First in Watercolor” awarded in 1932.

He continued to travel, making painting excursions to North Carolina and the Deep South, and in the 1940s he made a number of excursions, producing paintings of cowboys in the vast landscape that bring to mind scenes in a John Ford Western, and which show a truly remarkable ability to capture the weather effects— perhaps streaks of rain descending from distant clouds, or complex patterns of moving shadows and flickering light. Interestingly, Wilcox did not drive, but would sit in the front seat sketching while others drove for him. One of the more curious artifacts of his career are long landscape scrolls, a bit like those of Chinese art, sometimes twenty feet long, which he would produce by sketching continuously during a long drive. In his final years, after his retirement, working entirely from imagination and memory, he produced a memorable series of “Little-Big Paintings”, several of which are in this exhibition, and record the scenes of rural life in Brecksville that he had witnessed when he was a child. These were the subject of one of the final critical tributes he received in his lifetime, a glowing article by Norman Kent in American Artist, February 1963, just a year before his death, praising the way in which these works achieved a monumental effect within the space of a few square inches.

Amazingly well-organized, Wilcox kept comprehensive ledgers listing every painting he made, and in many instances providing a grade, if he thought it was an exceptional work. While his work sold well, his position as a teacher spared him from the need to sell everything he made. As a result, many of his best watercolors have remained in the family, where they were carefully stored, and not exposed to light. Today they are as luminous and fresh as the day they were made.