24 minute read

TheWoodmereAnnual 81ST JURIED EXHIBITION

CONTENTS

Foreword by William R. Valerio 2

A Conversation with Doug Bucci 4 Works in the Exhibition 22

It is a privilege to work with Doug Bucci as the juror of the 81st Woodmere Annual, the exhibition of Philadelphia’s contemporary art held each summer in our Catherine M. Kuch Gallery and Dorothy J. del Bueno Balcony Gallery. Bucci possesses a unique creative sensibility, and he arrived at his practice through a journey in the design arts, specifically in jewelry and metalsmithing. As the organizer of our show, he attracted a broad range of creative individuals, many of whom, like him, cross boundaries between traditional practices in the fine arts—painting, sculpture, the graphic arts—and the functional or applied arts. Moreover, Bucci embodies a quality we seek in all of our jurors: an innate enthusiasm for the work being done by fellow artists—especially young artists—in and around Philadelphia. The show is as interesting as it is beautiful, and Woodmere is grateful.

We ask each year’s juror to include their own work in the exhibition, and we are thrilled to present for the first time Bucci’s Islet | White Sectional, Neckpiece (2010–21), an important recent acquisition destined for the galleries we are building in our new space, Frances M. Maguire Hall, to showcase the history of Philadelphia’s jewelry arts. Bucci lives with diabetes, and his work is informed by a passion to understand his own body’s chemistry as well as a deep interest in the techniques—3-D printing and electroplating, for example—that are the tools of jewelry makers and metalsmiths around the world today. The various rings of the neckpiece are shaped by the data readings taken from different parts of Bucci’s body on a single day. Although most who encounter the work’s visually arresting presence wouldn’t know, it is in fact a self-portrait: blood count from the head, blood count from the chest, blood count from the hips, and so on.

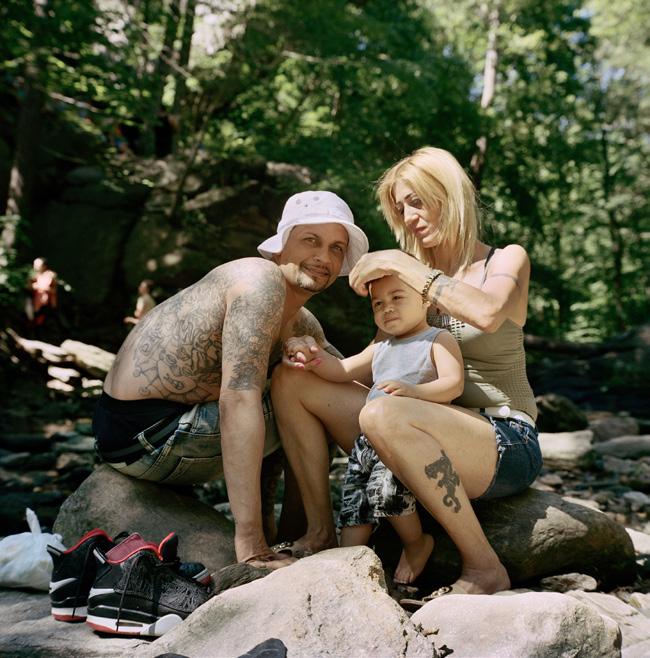

We also ask our juror to devise a call to artists that will drive exploration of a theme that is central to their own work. Bucci’s call is about “connections,” or more specifically about the connection between the body and its science in relation to an idea of place. This place is, of course, Philadelphia, with its unique cultural, physical, and historical characteristics. In some entries, like Devil’s Pool Bathers #9 (2021) by Sarah Kaufman, the sense of body and place is straightforward. I have lived in Philly long enough to know that if I saw Kaufman’s photograph in a gallery on the other side of the planet, even without the title, I would know immediately that it’s about the Wissahickon and the people who make this city their home. There’s a distinct Philadelphia posture and bodily attitude that is captured by many of the artists in the show. Other works refer to our city in more oblique ways such as an ensemble of rings made by Theophilus Annor, an artist from Ghana who is studying at Temple University’s Tyler School of Art. He uses digital printing and metalwork techniques that were developed in Philadelphia, to reimagine traditional African adornments. This city is a place of down-to-earth, practical applications of science to art and culture that can be traced back to the eighteenth century and such phenomena as Peale’s Museums and Benjamin Franklin’s printing press.

Woodmere is very proud that the Annual has become a high point in the yearly cycle of contemporary art in Philadelphia. We thank supporters the Drumcliff Foundation, Jeanne Ruddy and Victor Keen, and an anonymous donor for underwriting the show as they have many times before. As always, the exhibition would be impossible without the dedication, creativity, and talent of Woodmere’s staff: Rachel Hruszkewycz, Hildy Tow, Laura Heemer, and Rick Ortwein. I feel lucky to work with such wonderful people. And finally, we are deeply grateful to Doug Bucci, who continues to be a terrific partner for the Museum in this and many other projects.

WILLIAM R. VALERIO, PHD

The Patricia Van Burgh Allison Director and Chief Executive Officer

A Conversation With Doug Bucci

On March 17, 2023, juror Doug Bucci spoke with Woodmere Associate Curator Rachel Hruszkewycz, Robert L. McNeil, Jr. Curator of Education Hildy Tow, and Patricia Van Burgh Allison Director and CEO William Valerio about his selections for the Woodmere Annual: 81st Juried Exhibition. Bucci asked artists to submit works that explore novel and infinite ideas and methods of connection.

WILLIAM VALERIO: It’s great to be getting ready for Woodmere’s 81st Juried Exhibition. Each year, the show is a new experience, driven by our juror, their interests, and the artists who apply. Thank you, Doug, for being our juror this year. You are known as an artist who makes jewelry, working with the science of the human body as well as new materials and methods, including 3-D printing, which is one of the technologies changing many aspects of life as we know it. Your call to artists for the exhibition was about connection. How did artists respond?

DOUG BUCCI: I wanted a call that was broad but very much of and about Philadelphia in a larger sense. The submissions gave us an amazing visual array of what Philadelphia looks like. We have the people represented, and we have ideas represented.

I came to this idea of connectivity because Philadelphia, geographically, is in this connected place where bodies of water stream together—the Delaware and the Schuylkill. I love that the city is so accessible. The people are accessible. Major art schools and universities are helping to connect communities of people. Museums like Woodmere, the Museum for Art in Wood, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Clay Studio, the Print Center, and many others all serve to connect people.

In reviewing the submissions, from a practical standpoint, I started with a surface kind of survey, by looking at this as a visual experience, considering the 300-plus artists, looking at all the work that was being presented.

My next pass was looking in terms of the language that supported the art and how the artists addressed the theme. I know what my initial reads were, but I also found it really interesting to read how the artists put the work into context.

Some of the work that I was really taken by was Kathleen Greco’s. What at first appears to be fields of smudged color is actually flower petals. It’s an almost Victorian approach to memory and sentiment, and it really moved something from the past into the present. We press flowers because we’re trying to capture a moment or a sense of beauty from a particular period of time.

HILDY TOW: There’s something poignant in the connection with Victorian flowers that contained secret messages. Victorians developed an elaborate symbolism for flowers, for example, pink carnations symbolized gratitude and fascination.

BUCCI: That made a connection to time and place for me, which was quite amazing. I also found that to be true in Kathryn Gegenheimer’s Silver Linings it’s this lush, engaging, almost loving diptych. I also kept coming back to it in terms of its scale. I imagined how visitors would see it and experience it for the first time.

TOW: The artist notes that the two canvases could be displayed next to each other or across the room.

BUCCI: In dialogue.

TOW: I like the idea that they’re communicating across the space.

RACHEL HRUSZKEWYCZ: The Kuch and del Bueno galleries where the show will be installed are round spaces with curved walls, which let visitors see across the entire space.

BUCCI: Yes. The longing and loving that I feel from these paintings is maybe even strengthened by having them gaze at one another across the gallery.

TOW: When you look closely, you see that they’re not replicas. There’s no doubt about their similarities, but there are changes, which add another nuance.

HRUSZKEWYCZ: I’m always impressed by the range of media and disciplines among the submissions, from brass and bronze to 3-D printing and traditional printmaking and photography.

BUCCI: I have a dear friend who said to me, I’m so sorry you have to do this jurying. And I was laughing about that because it’s difficult. It took me longer than I thought to review everything because for the artists that didn’t write about their work, I Googled them. I went through their websites. I read their artist statements. I looked at their other work and developed a better sense of their identity. There was this amazing sense of discovery.

One thing I’m starting to really figure out about Philadelphia, being a working artist, being an educator here, is that as much as we think we know about the city we live in, there’s always an unturned stone. I’m often guilty of being within my own community to a fault. The selection process was a deep dive into different practices. I considered established artists, individuals who were midcareer, and up and coming—that were exciting. I was looking at this on multiple levels, and as a result we have a number of people who are new to Philadelphia, and to me.

HRUSZKEWYCZ: And new to Woodmere. There are many artists whose work we’ve never shown before.

BUCCI: We have ceramicists. We have jewelers. We have fiber artists. We have painters. We have sculptors. And we have people who bridge disciplines—thinking as far back as Thomas Eakins and The Gross Clinic (1876), Philadelphia has had a confluence of art and science. Two artists in the present show who bridge disciplines are Lauren Cassidy and Marguerita Hagan. Their works present another world, or the magnification of a world. Magnification brings people into another realm and lets them see something for the first time.

Hagan’s subject is diatoms—microscopic, unicellular silica organisms in water. Her work acknowledges the discoveries by Dr. Ruth Patrick, an expert in diatoms and founder of the field of river ecology, and Dr. Marina Potapova, an associate professor in Drexel University’s Department of Biodiversity, Earth, and Environmental Science and an assistant curator of diatoms at the Academy of Natural Sciences. Their discoveries present the micro and the macro relationships of the world.

Cassidy is working with science and visualization. She visualizes sounds by taking the base, the treble, and other sounds, and showing them in shape and color.

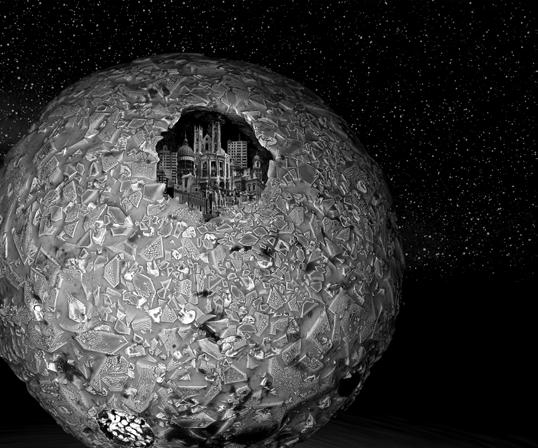

Leah Modigliani works as if she is world building under a microscope, or discovering a lost civilization. These could be cellular organisms. She’s developing these dystopian worlds of small planets. These three artists are doing similar things but in diverse ways.

City of God (San Francisco, 1906), 2021, by Leah Modigliani (Courtesy of the artist)

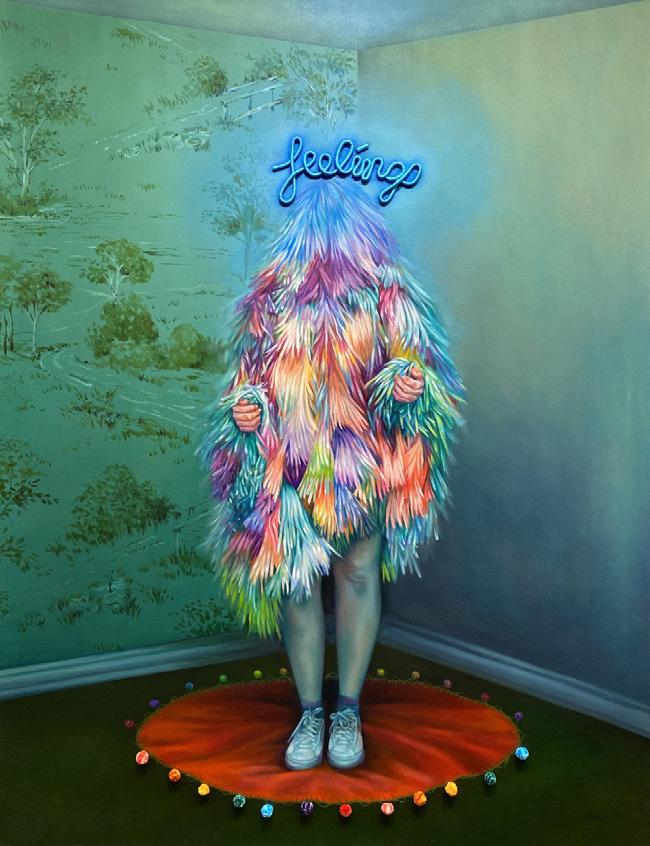

VALERIO: A work that intrigued me is Sarah Detweiler’s Feelings. Is this a painting or a sculpture?

HRUSZKEWYCZ: It’s an embroidered canvas.

BUCCI: Yes, the work has a textural quality and depth. There’s a painterly approach, steeped in a craft sense of making. Craft has become a part of the fine art world. Construction, fabrication, and materiality are big parts of what’s going on in painting and sculpture.

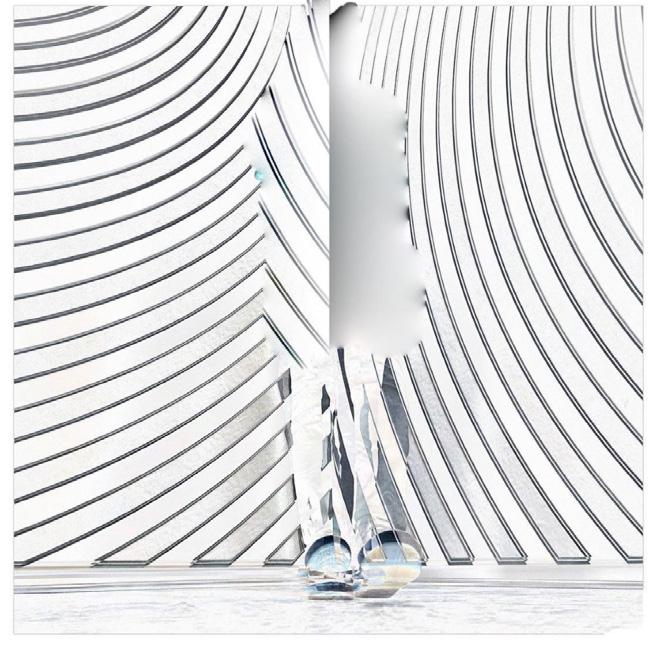

VALERIO: You were talking about how this interdisciplinary approach ties into a specific cultural history in Philadelphia. I’m thinking back to Benjamin Franklin inventing useful objects like the “Franklin stove,” the lightning rod, or bifocals, and new civic institutions like fire departments and circulating libraries. Philadelphia is a city where we figure things out. We are makers, innovators, doers. There’s this practical sensibility when it comes to science. I wanted to ask you about the jewelry by Ju-hyung Park, which is beautiful and elegant; the geometry makes me think of a crystalline structure.

BUCCI: Park is from Seoul—he’s studying here in Philadelphia. This piece is brutalist in its form, but the surface, the quality, the scale, is not.

VALERIO: The light and dark relationships are dramatic, visually stunning.

BUCCI: Talking a little bit about Woodmere’s collection here, when I walked in this afternoon, I had a moment to stand there and honor William Daley’s Guardian Vesica (2005)—it’s this amazing vessel that lets you look at the architectonics of his form, the inside, outside relationship. Daley had a connective practice of ceramic and craft and industrial design and merging those areas together in practice.

Park’s piece begins to do that. Philadelphia has a strong legacy of merging disciplines, much like Tyler emeritus, Stanley Lechtzin—who was the head of the Metals/Jewelry/CAD-CAM program at Tyler School of Art and Architecture at Temple University—he melded art and science in his electroformed neckpieces and brooches and jewelry. Electroformed jewelry came from Philadelphia—electroforming is the process of applying a metal coating on an object. Lechtzin was also the pioneer of computer-aided design and 3-D printing in the jewelry field.

TOW: Steve Donegan’s work is electroformed copper.

BUCCI: Donegan has been really integral in the environmental impact of electroforming and electroplating, developing safe practices.

VALERIO: He’s a member of the family here at Woodmere.

BUCCI: His process starts with a wax form (or mandrel), where he creates textures and patterns, similar to what we see in the fully formed work. After that, he uses electrodeposition to grow metal on the surface of the wax until it reaches a desired thickness.

To go back a bit, I’d also like to talk about the partnership between Emily Cobb and Mallory Weston. Their JV Collective operates out of a studio located in South Philadelphia’s Bok Building, the former home of Bok Vocational High School. Weston is a fellow faculty member of mine in the Metals/Jewelry/CAD-CAM program at Tyler. Her work focuses on floral forms and capitalizing on the specular uses of space age material like titanium. Since joining Tyler, she has incorporated 3-D printing and modeling into her practice.

She and Emily Cobb (a 2012 Tyler alum) collaborated on Ssssmiley Face. While their art is not wearable, Ssssmiley Face is remarkable in part because it was created between Philadelphia and Eureka, California.

HRUSZKEWYCZ: Yes, they described this project as part of their submission. They explained that they completed this life-size cobra while living on opposites sides of the country from each other. Cobb made the main structure in Eureka using CAD modeling and 3-D printing, dividing the form into multiple parts that she mailed to Weston. In Philadelphia, Weston applied the intricate metal patterning to the surface. Finally, all of the components were mailed back to Cobb, who applied the final gold leaf finish and performed the final assembly.

VALERIO: It’s remarkable. There’s more beautiful jewelry in the show, like the pieces by Theophilus Annor. How does he work?

BUCCI: Annor is a graduate student in the Metals/ Jewelry/CAD-CAM program at Tyler. He’s originally from Ghana, and incorporates Ghanaian symbols into his work.

VALERIO: How does he make these bronze, knot-like rings?

BUCCI: He uses a combination of lost-wax casting and 3-D printing. He starts by digitally creating a model of the rings, which is then sent to the printer’s software and virtually sliced, layer by layer, as you might slice a loaf of bread. The printing process then builds up the object layer by layer, using lasers to cure each section with a photopolymer wax resin.

This is using what’s called stereolithography—using a laser to cure each layer consecutively stacked one on top of one another in wax.

3-D printing has opened up so many possibilities, such as extrusion. Others use lasers to fuse materials together while they’re still in a green state, before firing. In the case of wax, it’s used in a stereolithography printer along with a photopolymer to create a wax and photopolymer blend. This is then covered with an investment ceramic shell, the wax is burned out, and the bronze is lost wax cast centrifugally.

TOW: You have the mold, so you can keep casting.

BUCCI: Or you can keep printing from the file without the need for a mold. So, the question arises, where does the true labor lie: in the file or the physical object? Ultimately, I believe that depends on the artist’s intent.

TOW: Well, it’s like a lot of conceptual work too— the idea is also the creative part.

VALERIO: Multiple versions of the same print can come from the same woodblock or etching plate. But you wouldn’t say that the woodblock or the plate is the finished work, just the way you wouldn’t say the digital file is the work.

HRUSZKEWYCZ: One of the most clever—and funniest—works in the show is Maxwell Davis’s Rabbit

BUCCI: It’s a fabricated object with a found object—a vibrator! The ring where you insert your fingers is made of soft fabric. Davis is also a graduate student at Tyler. This is an early piece of his from when he came into the program. I see him as a visual disruptor, disrupting form and disrupting an idea. Is it wearable? Is it functional?

HRUSZKEWYCZ: Putting your fingers into it to wear it is also sexually suggestive, but as I said it’s also funny.

BUCCI: One way we connect and engage with others is through humor. It can convey deep messages or ideas that are difficult to express in words. Sometimes, using humor can make people more receptive to a message.

VALERIO: The object’s function is to make people curious. Visitors will probably approach this as we all did, thinking, “what is that?”

One of my questions for you is how does Paul DuSold’s work fit in to this exhibition? It’s a traditional painting with a classical subject. He shows us Endymion’s male gaze and Diana’s female body as object of that gaze.

HRUSZKEWYCZ: DuSold reverses the story from Greek mythology. Diana was the goddess of the moon. According to the National Gallery of Art, “When Diana first saw the young shepherd Endymion sleeping in the shelter of a cave, she instantly fell in love with him. Quiet as moonlight

Evidence of Unknown Markers in she entered the cave and gently kissed his closed eyes. This kiss selfishly cast Endymion into an immortal sleep so that she could adore him forever. Ancient poets said that somewhere, high in the mountains of Greece, Endymion still sleeps in a hidden cave with his sheep and dog nearby. Ancient belief was that on nights of the new moon, when it was hidden from view, Diana left the sky to be at Endymion’s side.” In DuSold’s painting, Diana is asleep and it is Endymion who gazes at her. Her body is on display. He’s looking down at her.

VALERIO: DuSold is a teacher in Woodmere’s studio program and he too is a member of the family here. He is devoted to the great traditions of figurative painting in Philadelphia. He also takes his inspiration from Renaissance art.

BUCCI: This is the most traditional piece out of all the work. There’s a connection historically to Philadelphia, and that historic sense of painting and training. I’d like to contrast this traditional depiction with something from the opposite end of the spectrum.

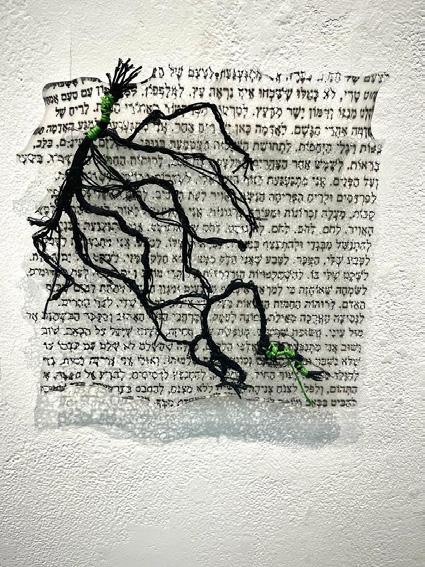

HRUSZKEWYCZ: Vita Litvak’s photograph is an interesting contrast.

VALERIO: Both DuSold and Litvak depict figures in nature, but Litvak depicts a very different kind of relationship. The figure who’s got the active gaze in her work is the woman. I mean, it kind of turns the tables—we’re just seeing his feet.

BUCCI: The two works create a dialogue about the male gaze versus the female gaze.

HRUSZKEWYCZ: Doug, I’d like to talk about your own work in the show, Mellitus

BUCCI: I’ve been a type 1 diabetic my entire life and I’ve incorporated this aspect of my life into my work. I wear a continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) system that checks my blood sugar levels at five-minute intervals throughout the day, twentyfour hours a day.

When I was younger, relying on a CGM for my diabetes management felt discouraging. But with the advent of the insulin pump, everything became digitized. My medical data was automatically logged into spreadsheets, which gave me new opportunities to manipulate the system. I eventually discovered a way to create a receiver that let me access and extract data from my insulin pump via its radio frequency, which could be integrated into CAD software. Using numbers, I was able to start taking that information and allowing that information to control objects and the outcomes of objects.

My objective was to represent a physical manifestation of a digital state. I thought about how to transform intangible numerical data into tangible forms. How could I create objects that were either emanating from or impacted by this digital realm?

My first objects look like a science fair project. It’s three bracelets I made while I was planning the Society of North American Goldsmiths conference here in Philadelphia in 2009.

The initial object’s sparse appearance was a clear reflection of my poor health caused by stress and a lack of self-care and proper nutrition. As I started to calm down during the conference period, the subsequent object exhibited a fuller form and more data points. Three months later, the bracelet took on a fully rich and plump appearance, indicating a significant improvement in my overall health. This experience validated my belief that I could transform digital medical data into physical objects with form and substance.

VALERIO: There’s something of a twist to the realist tradition of the arts in this. You’ve figured out how to manifest dispassionate biological information in another physical form.

BUCCI: This will be the first time it’s shown in Philadelphia.

VALERIO: That’s fantastic. Another of your amazing pieces in our collection—Islet—is also informed by your cells, blood counts, sugar. A beautiful contrasting point to this work is Rosalind Sutkowski’s Fungi Neckpiece. She uses technology to depict nature but in a completely different, expressionistic way.

BUCCI: What’s wonderful especially with Fungi Neckpiece is that we begin to come back to the point of using technology to bring nature into the picture, and the way to control it or harness it.

I see my work as a confluence of art and medicine, although I never actually practiced medicine myself. Recently, there’s been a growing discussion within medical schools regarding the role of perception, with many of them incorporating art appreciation into their curricula.

TOW: We host medical students from Jefferson. Looking at art helps them become better able to notice things about their patients that aren’t revealed in diagnostic tests.

BUCCI: As artists, one of our key traits is perceptiveness. We approach things from a fresh viewpoint, comparing and contrasting in unconventional ways. While we may learn the rules, we also push the boundaries by breaking them.

TOW: What’s interesting about artists and perception is that an artist is going to have a perception and create this work, but then there are the perceptions of others who are looking at it. I don’t think any artist would claim to know everything about their artwork. I know what I’m doing. I know what I’m concerned with. I know what I responded to and how I made it change or grow.

But then somebody who’s not in the artist’s head is looking at the work with fresh eyes and often seeing something else. That’s where dialogue can happen.

BUCCI: In my view, jewelry is a powerful means of communication. It’s a form of art that initiates a conversation and creates a connection with the world. (Former US Secretary of State) Madeleine Albright’s jewelry, for instance, was carefully chosen based on the context she was in, and what needed to be communicated. It could be a simple pin, a brooch, or even an art piece. Jewelry, in my opinion, is a remarkable tool for effective communication.

VALERIO: I have to ask you about John Wind’s piece. It looks like plaster poured into a plastic bottle and allowed to overflow.

BUCCI: These are monuments. He wanted to depict a monument to the “everyman” using ubiquitous materials such as water bottles, wood scraps, and plastic.

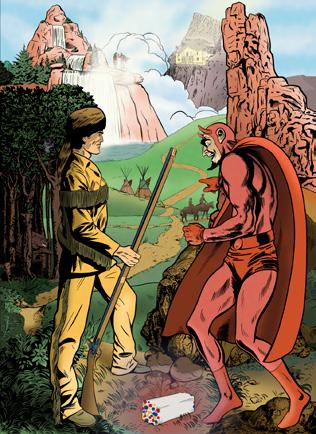

VALERIO: There’s a masculinity to the object and there’s a lot of masculinity in the show. In Matthew Borgen’s work, it looks like Davy Crockett meets the devil.

BUCCI: Yes, the perversion between Davy Crockett and the devil—it’s temptation.

TOW: There’s a bag of Wonder Bread at their feet.

BUCCI: This is a perversion of the environment.

VALERIO: Completely fascinating. Next, I’d like to ask about Darla Jackson’s ring.

BUCCI: Her piece is a set of brass knuckles. Although she specializes in figurative sculpture, I decided to focus on the jewelry aspect as it deviates from her typical sculptural works.

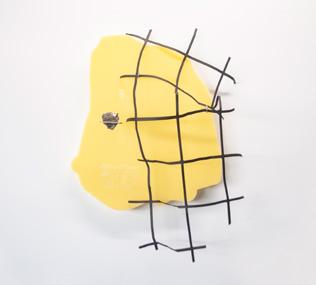

VALERIO: The birds are so delicate because they’re perched on the rings. I’m also curious about Keith Micheal Murphy’s brooch.

BUCCI: Murphy is a former Tyler student. He works with fiber mounted on plaster. I find it particularly thrilling to have his work in conversation with the other pieces. His artistic interests lie in adornment—a means to be noticed and seen. His work, akin to a flower, raises the question of how one can entice another’s gaze.

VALERIO: Doug, when I arrived at Woodmere thirteen years ago, part of our concept for revitalizing the annual exhibition was to engage with interesting artists and to think about the art being made in our city from the perspective of our juror’s interests.

That comes across very clearly in your installation. The show shines a light on who you are—not that anything looks like your work, but the avenues of interest are all related.

BUCCI: Thank you very much. I’ve enjoyed the whole process and I can’t wait to see the exhibition.

Works In The Exhibition

JILL ADLER

American, born 1996

Blackout from the Past, 2022

Single-fold screenprint on archival newsprint, 12 x 11 in. (folded)

Courtesy of the artist

THEOPHILUS ANNOR

Ghanaian, born 1999

Loyalty, 2023

Bronze, 1 1/8 x 1 x 1 1/4 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Agyinduwura (Loyalty), 2023

Bronze, 1 1/4 x 1 x 1 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Holding On, 2023

Bronze, 1 1/8 x 3/4 x 1 in.

Courtesy of the artist

MARTIN BERNARD BERNSTEIN

American, born 1941

Drive-By Visit, 2021

Archival pigment print, 11 x 15 in.

Courtesy of Space Gallery Philadelphia

MATTHEW BORGEN

American, born 1974

Temptation in the Wilderness, 2019

Inkjet print on archival paper, 54 x 42 in.

Courtesy of the artist

FRANK BURD

American, born 1946

The Subway, 2016

Digital print, 8 x 10 in.

Courtesy of the artist

LAUREN CASSIDY

American, born 1997

Dir, Dir Jehova, Will Ich Singen, 2021

Acrylic on stretched canvas, 22 x 28 in.

Courtesy of the artist and Viridian Artists Gallery

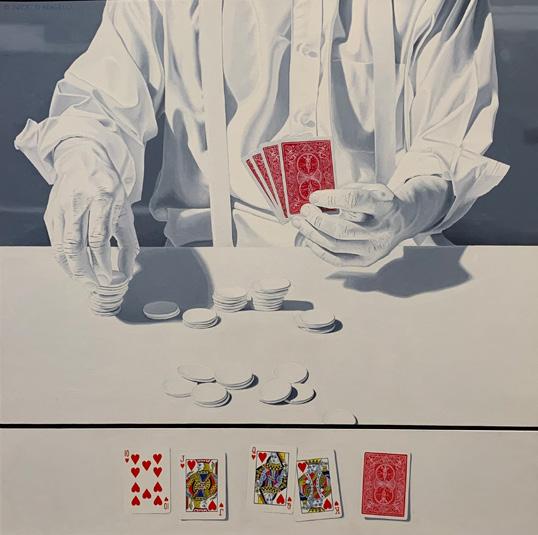

NICK D’ANGELO

American, born 1970

All In, 2023

Oil on panel, diptych, 28 x 28 in. overall

Courtesy of the artist

MAXWELL DAVIS

American, born 1991

Rabbit, 2022

Brass, powder coat, flock, and found object, 6 x 2 x 1 in.

Courtesy of the artist

CHRISTINA DAY

American, born 1977

Climber, 2019

Hand-cut and collaged salvaged linoleum, 15 1/4 x 17 3/4 in.

Courtesy of the artist

BRIAN DENNIS

American, born 1959

Memory Hack (Stepping Through), 2022

Photomontage print on paper, 40 x 40 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Nothing Like You Has Ever Been Seen Before, 2017, from the series Gold by Cavin Jones (Courtesy of the artist)

SARAH DETWEILER

American, born 1979

Feelings, 2022

Oil, rope, and embroidery thread on canvas, 50 x 38 x 2 1/2 in.

Courtesy of Paradigm Gallery, Philadelphia

STEVEN DONEGAN

American, born 1951

Industrial Hub #1, 2021

Electroformed copper, 15 x 15 x 10 in.

Courtesy of the artist

PAUL DUSOLD

American, born 1963

Diana and Endymion, 2022

Oil on canvas, 66 x 64 in.

Courtesy of the artist

CHARLES EMLEN

American, born 1957

Quasi-Autonomous, 2021

Painted steel and shovels, 84 x 50 x 96 in.

Courtesy of the artist

IVA FABRIKANT

American, born 1986

Black Triflower, 2020

Recycled paper pulp and ink, 12 x 13 x 13 1/2 in.

Courtesy of the artist

KATHERINE FRASER

American, born 1980

The Messenger, 2020

Oil on canvas, 32 x 44 in.

Courtesy of Rachel and Cody Bannon

TERRI FRIDKIN

American, born 1955

Connections, 2018

Woodcut, chine collé, and intaglio on artist-made paper, 30 x 24 in.

Courtesy of the artist

KATHRYN GEGENHEIMER

American, born 1984

Silver Linings, 2022

Oil on canvas, diptych, 40 x 80 in. each

Courtesy of the artist

KATHLEEN GRECO

American, born 1957

In Lieu of Flowers / Carnations, 2021

Flower petals, 36 x 28 in.

Courtesy of the artist of

Likely

MICHAEL GROTHUSEN

American, born 1966

USA—Double Slump, 2005

Steel, 36 x 30 x 15 in. each

Courtesy of the artist

MARGUERITA HAGAN

American, born 1959

Flourish, 2021

Ceramic, glass, mahogany, and steel, 10 x 11 x 7 in.

Courtesy of the artist

NOA HAGILADI

Israeli, born 1978

In the Beginning, It Is Always Dark, 2022

Glass and embroidery, 10 x 10 in.

Courtesy of the artist

ELIZABETH HAMILTON

American, born 1981

Derby Plate I and II, 2021

From the series Private Collection

Paper plates, watercolor, and acrylic gold paint, 9 x 9 x 1 in. each

Courtesy of the artist

DARLA JACKSON

American, born 1981

This Will Hurt Me More Than It Hurts You . . . , 2021

Polyurethane resin, 4 x 5 1/2 x 3 1/2 in.

Courtesy of the artist

CAVIN JONES

American, born 1957

Nothing Like You Has Ever Been Seen Before, 2017

From the series Gold

Acrylic on canvas, 60 x 48 in.

Courtesy of the artist

SARAH KAUFMAN

American, born 1981

Devil’s Pool Bathers #9, 2021

Archival pigment print from medium-format film, 40 x 40 in.

Courtesy of the artist

DAWN KRAMLICH

American, born 1987

Forever No Matter V, 2023

Nails and laser-cut matboard from hand-cut templates, dimensions variable

Courtesy of the artist

ANDREA KRUPP

American, born 1962

Now’s the Time to Make by Spending, 2023

From the series Seeing Coal

Hand-polished anthracite coal, board, iPhone, and cord, 15 x 5 x 5 in.

Courtesy of the artist

DIANE LACHMAN

American, born 1946

Silent Echo 1, 2021

From the series Silent Echo Digital photograph on Hahnemühle paper, 12 x 18 in.

Courtesy of the artist

VITA LITVAK

Moldavian, born 1980

Evidence of Unknown Markers in Time #9, 2008–2023

Archival inkjet print, 30 in. diameter

Courtesy of the artist

MICHELLE MARCUSE

American, born 1957

Treehouse III, 2021

From the series Silo

Raffia, paint, foamboard, paper, and cardboard, approx. 90 x 32 in.

Courtesy of the artist

CAITLIN MCCORMACK

American, born 1988

Low Country Special, 2021

Crocheted cotton fiber sculpture, 14 x 25 x 12 in.

Courtesy of the artist

MICHAEL MCGEEHAN

American, born 1952

My Father’s Father’s Shillelagh, 2022

Blackthorn and gold, 35 x 2 x 1 1/2 in.

Courtesy of the artist

LEAH MODIGLIANI

American, born 1970

City of God (San Francisco, 1906), 2021

Archival inkjet print on rag paper, 29 1/2 x 34 1/2 in.

Courtesy of the artist

KEITH MICHEAL MURPHY

American, born 1993

Glamour, 2022

Powder-coated brooch with appliqué and fringe, 6 x 6 in.

Courtesy of the artist

LIISA NELSON

American, born 1985

Entropy (Work Early, I’ll Get It

Later), 2017

Ceramic, 6 x 6 x 9 in.

Courtesy of the artist

JU-HYUNG PARK

South Korean, born 1985

A Facade, 2023

Aluminum and stainless steel, 5 x 4 1/4 x 4 1/2 in.

Courtesy of the artist

HEATHER RAQUEL PHILLIPS

American, born 1974

Reclamation | Liberation, 2019

Felt, sequins, fringe, and cotton blend, 24 x 38 in.

Courtesy of the artist

WALTER PLOTNICK

American, born 1958

Bird Hotel, 2022

From the series Surprise Inside Silver halide print, 16 x 20 in.

Courtesy of the artist

DEBORAH RICCARDI

American, born 1965

Hope after Disaster, 2022

Archival print on fine art paper, 7 x 10 1/2 in.

Courtesy of the artist

MATTHEW SPEEDY

American, born 1988

Slag, 2022

Acrylic, steel, tar paper, and schist, 20 x 16 x 5 in.

Courtesy of the artist

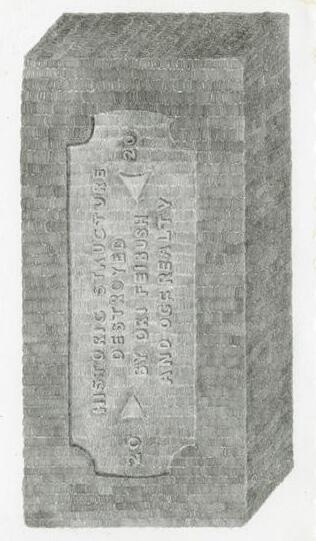

C. J. STAHL

American, born 1983

This Is Your Ballot, 2020

Graphite on paper, 10 x 6 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Historic Structure Destroyed by Ori Feibush and OCF Realty, 2020 Graphite on paper, 10 x 6 in.

Courtesy of the artist

GORDON STILLMAN

American, born 1984

Unfolded Boat, 2018

Cyanotype on BFK Rives paper, 22 x 30 in.

Courtesy of the artist

TODD STONG

American, born 1991

There Am I, 2022

Monotype with flashe, 72 x 55 in.

Courtesy of the artist

BRANDON AQUINO STRAUS

American, born 1991

Bahay ni Inang [My Grandmother’s House], 2022

Digital polyester print, bamboo mounted, 90 x 70 in.

Courtesy of the artist

PATRICIA SULLIVAN

American, born 1966

Upcycled Reimagined Gemstone Object No. 1, 2019

Upcycled fibrous material, thread, and digital drawing, 5 3/4 x 2 1/8 x 1/2 in.

Courtesy of the artist

ROSALIND SUTKOWSKI

American, born 1963

Fungi Neckpiece, 2018

Silicon, inkjet on fabric, and gold powder, 16 in. round

Courtesy of the artist

BLAISE TOBIA

American, born 1953

Double Negative, 2022

From the series Slight Permutations of the Surface

Archival inkjet print, 22 x 17 in.

Courtesy of the artist

MAT TOMEZSKO

American, born 1986

Portrait of an Artist (True Stories 1), 2022

Acrylic on panel, 20 x 16 in.

Courtesy of the artist

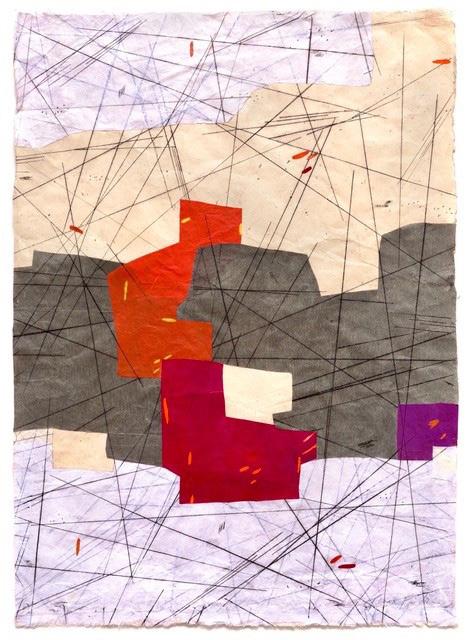

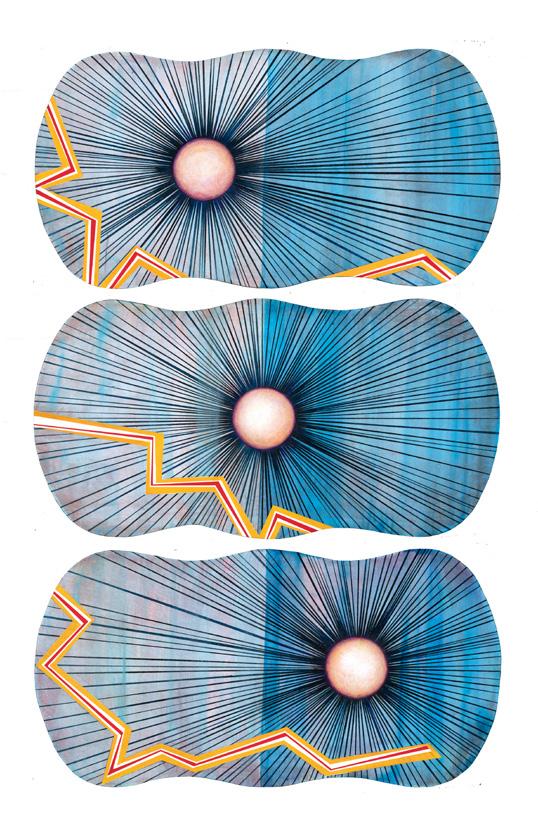

ROBERTA TUCCI

American, born 1962

Chance of Storms: Likely, 2022

Acrylic on panel, triptych, 58 x 31 in. overall

Courtesy of the artist

PEGGY WASHBURN

American, born 1963

Growth, 2023

Mixed media and encaustic on canvas, 30 1/2 x 20 1/2 in.

Courtesy of the artist

MALLORY WESTON

American, born 1986

EMILY COBB

American, born 1987

Ssssmiley Face, 2017

Nylon, metal leaf, gold-filled bronze, and 18-karat yellow gold-plated brass, 11 1/4 x 12 1/4 x 18 1/2 in.

Courtesy of the artists

JOHN Y. WIND

American, born Israel 1961

Monuments to Everyman (Neon #1, 2, 3), 2023

From the series Monuments to Everyman

Plaster, plastic, paint, and wood, dimensions variable

Courtesy of the artist and James Oliver Gallery

Work By Juror

DOUG BUCCI American, born 1971

Islet | White Sectional, Neckpiece, 2010–21

Glass-filled nylon and sterling silver, 18 x 18 x 1 1/2 in.

Woodmere Art Museum: Museum purchase with funding generously provided by the Windgate Foundation, 2022

Mellitus, 2009

Mellitus bracelet, process illustration, insulin pump, and continuous glucose monitoring transmitter, 14 x 24 x 24 in. Courtesy of the artist

WORK FROM WOODMERE’S COLLECTION

STANLEY LECHTZIN

American, born 1936

Untitled, 1980

Electroformed silver

Wasserman,

Woodmere Art Museum receives state arts funding support through a grant from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, a state agency funded by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

©2023 Woodmere Art Museum. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission of the publisher.

Catalogue designed by Barb Barnett and Kelly Edwards, and edited by Gretchen Dykstra.

Front cover: Ssssmiley Face, 2017, by Mallory Weston and Emily Cobb (Courtesy of the artists)

Back cover: Drive-By Visit, 2021, by Martin Bernard Bernstein (Courtesy of Space Gallery Philadelphia)

THE WOODMERE ANNUAL: 81ST JURIED EXHIBITION 45