7 minute read

What is permafrost? An unaccounted-for emitter

Katie Constantine, Communications Intern

Sarah Ruiz, Science Writer

graphic by Nichole Chapman

Thawing Arctic soils have the potential to push us past our warming targets.

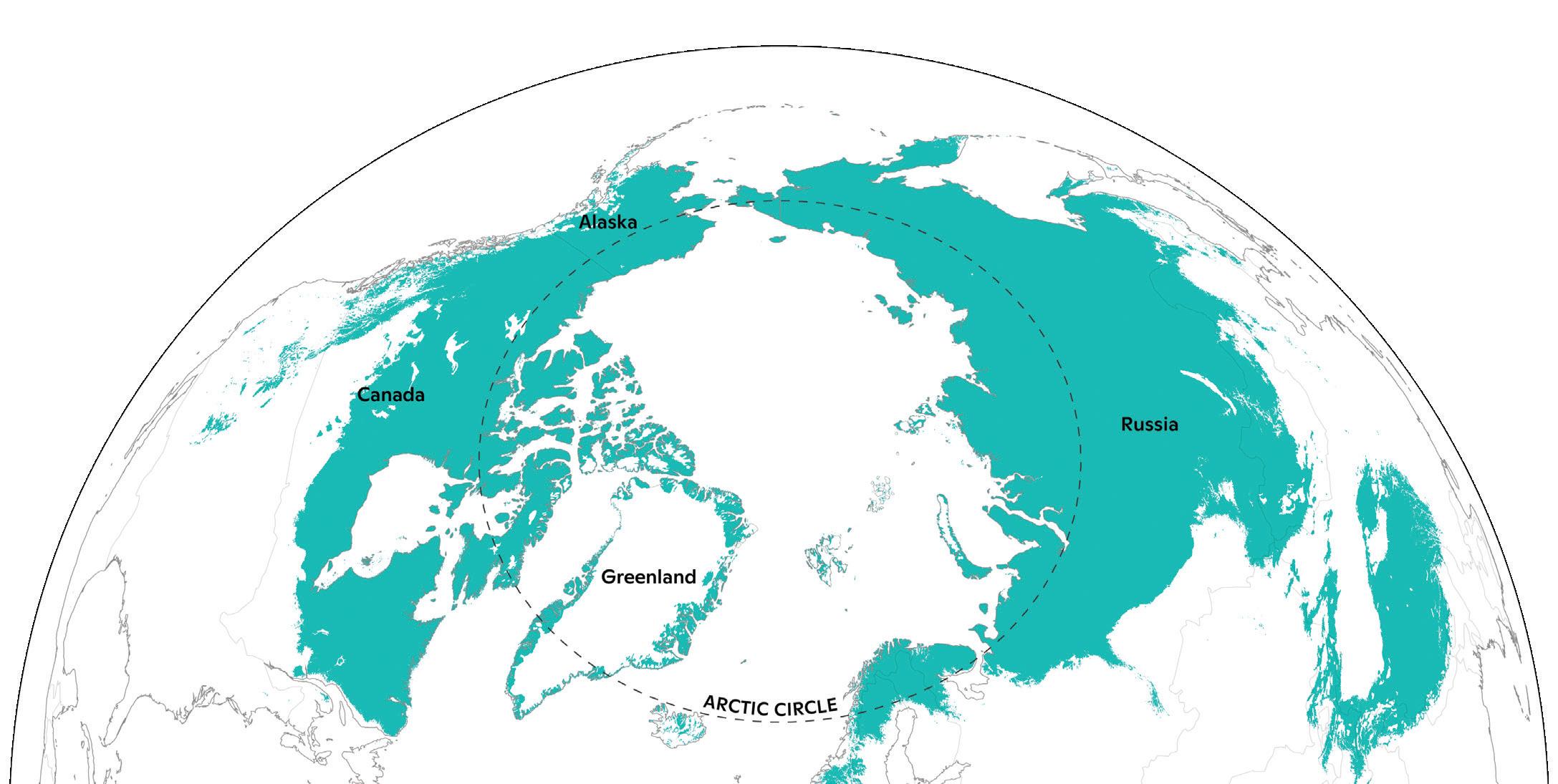

Located anywhere between a few centimeters to 4,900 feet below the Earth’s surface, permafrost is soil composed of sand, gravel, organic matter, and ice that has been frozen for at least two consecutive years. The most significant extent of permafrost lies in the Arctic—stretched across Alaska, Scandinavia, Russia, Iceland, and Canada. It can be found beneath the Arctic Ocean, the Arctic tundra, and alpine and boreal forests. It covers 15% of the land in the Northern Hemisphere, 3.6 million people live atop it, and it has the potential to release a devastating amount of carbon and rapidly accelerate warming.

Current extent of permafrost (green)

map by Greg Fiske

The thawing threat

Scientists estimate that Arctic permafrost contains 1.4 trillion tons of carbon, an amount more than double what is currently in the Earth’s atmosphere. That carbon sink is stable as long as it stays frozen, but when it thaws, soil microbes break down the organic matter in permafrost and release carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere, increasing the rate of warming that caused the thawing in the first place.

In many places, forests, plants, and peat act as protective insulation for Arctic permafrost. This insulation helps keep carbon-storing organic matter, like plants and animals, as well as bacteria and archaea, frozen in the permafrost. However, climate change is already causing the Arctic to warm three to four times faster than the rest of the planet. In addition to speeding decay, rapid warming also strips back permafrost’s protective layers with increasing fires and heavy summer rains that burn and erode away top soil layers, further accelerating thaw. In some places, permafrost thaws so abruptly that the ground can collapse. Developing infrastructure that requires deforestation and the placement of underground pipes further exposes permafrost to warming. Additionally, as sea ice melts, coastal Arctic permafrost is exposed to warmer waters. The combined result is extensive permafrost thaw across the region.

Researchers have been studying permafrost thaw to determine the size of the threat it poses, though eroding slopes and fragmenting infrastructure are making Arctic research even more challenging. In a recent TEDTalk, Dr. Sue Natali, Woodwell’s Arctic program director and senior scientist, cautioned that, “By the end of this century, greenhouse gas emissions from thawing permafrost may be on par with some of the world’s leading greenhouse-gas-emitting nations.”

A slope eroding due to permafrost thaw in Siberia.

photo by John Schade

The missing expense in a global budget

Despite the potentially vast scale of permafrost emissions, they are conspicuously absent from the global climate budget. The budget, developed by the international science community, details planet-wide emissions and weighs them against carbon sequestered by forests and other carbon sinks. It functions much like a household budget—where spending more than you earn can jeopardize your financial stability. In this case, putting too much carbon into the atmosphere will push us past internationally-agreed warming limits.

Scientists estimate that emissions from permafrost thaw will range from 30 to 150 billion tons this century—on par with top-emitting countries like India or the United States. It’s “especially alarming… that permafrost carbon is largely ignored in current climate change models,” says Dr. Max Holmes, President of Woodwell Climate Research Center. That’s because permafrost thaw emissions could take up 25–40% of our remaining emissions budget to cap warming at 2 degrees Celsius. To put it in perspective, imagine leaving the cost of rent out of your household budget. It doesn’t mean you don’t have to pay it, it just means you won’t be prepared when that bill arrives.

Permafrost emissions haven’t been factored into these budgets because solid estimates of them are difficult to create. The Arctic is huge and diverse, and spans multiple countries; onthe-ground data is sparse, leaving information gaps. To begin filling those gaps, Woodwell has partnered with the Arctic Initiative at Harvard Kennedy School, the Alaska Institute for Justice, and the Alaska Native Science Commission to connect experts in climate science, human rights, and public policy with frontline communities and high-level decision makers. The partnership, called Permafrost Pathways, will expand and coordinate a pan-Arctic carbon monitoring network to improve the accuracy of permafrost thaw emissions estimates. Improved data will put force behind the push to factor permafrost emissions into global carbon budgets, climate models, targets, and measures for mitigation and adaptation.

In addition, high-resolution satellite and aircraft-based observations and advanced computer modeling, will allow scientists to track the changing landscape in near real-time and more accurately project future emissions.

The demand for adaptation

Even without precision in the numbers, the impacts of permafrost thaw are already being felt in the Arctic. Because ice is an essential part of the ground’s structural integrity, it becomes unstable when it thaws. This leads to dangerous situations like landslides and sinkholes that threaten millions of people, particularly remote communities.

In 2019, a Yup’ik community that has lived in Newtok, Alaska for hundreds of years had to begin moving to higher, volcanic ground because the thawing permafrost under their town was causing disastrous floods and sinking infrastructure. According to Dr. Natali, who studies permafrost thaw in Yup’ik territory, “it’s a place where permafrost is on the brink of thawing, and will be thawed by the end of the century, if not much sooner.”

There is currently little government framework for adaptation, both within Arctic countries and internationally. The Yup’ik people had to reach out to a variety of government agencies, living without plumbing for decades, before the U.S. federal government finally awarded them support for relocation. The community paid a heavy price for it, though. Without proper policy in place to manage climate relocation, they had to bargain for government assistance, and in the end turned ownership of the land they were leaving over to the U.S. government.

The process took sixteen years from when Congress agreed to provide assistance to when their promises were put into action. Arctic communities do not have another decade and a half to wait for more refined data, so the Permafrost Pathways program is collaborating with local communities to develop Indigenous-led adaptation strategies. For many, relocation or infrastructure upgrades are needed urgently, but there is currently no process or resources to enable communities to move forward. With Arctic residents already feeling the brunt of climate change, the involvement of frontline communities is crucial in developing successful adaptation plans and effective policies.

Nunapitchuk, Alaska

photo by Rachael Treharne

The work remaining

Despite its big strides, Permafrost Pathways is still in its infancy and there is a long road ahead when it comes to tackling the complex issue of permafrost thaw.

In the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2021 report, permafrost thaw was named as an issue that should be included in carbon budgets and global reduction schedules, but it isn’t due to the lack of data. Continued data gathering is needed to speed up the inclusion of permafrost emissions in important decision-making, but governments need to act now to protect their citizens against the hazards they’re already facing from thaw. Integration of permafrost thaw risks into disaster policies and community-led adaptation frameworks will create clear planning and response procedures for the unstable future the Arctic is facing.

Examining a permafrost sample in the field.

photo by John Schade

Learning Opportunity

Want to dig deeper into permafrost? Enroll in Woodwell’s new online course offered through FutureLearn. It’s free, and available anytime you are.

Thawing Permafrost: Science, Policy, and Environmental Justice in the Arctic

Learn more: woodwellclimate.org/permafrost-course