Zulma Steele

Artist/Craftswoman

Foreword by Henry T. Ford

Tom Wolf

Derin Tanyol

Bruce Weber

Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild

FRONT COVER

Zulma Steele

Self-Portrait n.d.

Graphite on paper (page from sketchbook), 8 x 6¾ inches.

Collection of Janet Marsh Hunt.

BACK COVER

Zulma Steele

Lily, c. 1903–1904.

Hand-colored woodblock print, 12½ x 4¾ inches. Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild, Alf Evers Collection, Gift of the Douglas C. James Charitable Trust.

Zulma STeele: arTiST/craFTSWoman

Exhibition dates:

August 21–October 11, 2020

Curated by: Henry T. Ford, Derin Tanyol, Bruce Weber, and Tom Wolf

Catalogue design and production:

Abigail Sturges

caTaloGue SponSorS

Henry T. Ford

Douglas C. James

Paul Washington

ISBN 978-0-578-73292-3

Copyright © 2020 Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild

34 Tinker Street, Woodstock, NY 12498

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, without express written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Please refer all pertinent questions to the publisher.

miSSion STaTemenT

The Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild provides a vibrant center for arts and crafts in the beautiful and unique rural community of Woodstock, New York, while preserving the historic and natural environment of one of the earliest utopian arts colonies in America. It offers a unique and inspiring combination of residency, educational, exhibition, and performance programs that encourage creative collaboration among a diverse array of artists, students, arts professionals, and the public.

WoodSTock ByrcliFFe Guild Board oF direcTorS

Byron Bell

Joseph Belluck, Counsel

Linda Bodner, Treasurer

Oscar Buitrago, Secretary

Herb Burklund

Sam Freed

Henry T. Ford, Director Emeritus, Byrdcliffe Historian

Frances Halsband

Richard Heppner

John Koegel

Katharine L. McKenna

Catherine McNeal, President

Douglas Milford

Tani Sapirstein

Julia Santos Solomon

Abigail Sturges

Lester Walker

Paul Washington

Sylvia Leonard Wolf, Vice President

Douglas C. James, President Emeritus

Garry Kvistad, Chairman Emeritus

6 Foreword

Henry T. Ford

8 Zulma Steele

Artist/Craftswoman

Tom WolF

24 Zulma Steele and William Morris

Nature Conventionalized at Byrdcliffe

derin Tanyol

34 A Minister to the Eye

The Ashokan Reservoir Series by Zulma Steele

Bruce WeBer

48 Selected Works

99 Checklist of the Exhibition

103 Biographies

104 Acknowledgments

Co-Curator, Byrdcliffe Historian, Board Member Emeritus

In 1903, the first artists and craftspeople arrived at Byrdcliffe, invited by Ralph Radcliffe Whitehead and his wife, Jane Byrd McCall Whitehead. All were to share in the collaborative creative experience the Whiteheads envisioned. Professionally and personally, Ralph and Jane were well connected to the art world, their circle including John Ruskin, Birge Harrison, Arthur Wesley Dow, and, of course, Bolton Brown, one of Byrdcliffe’s founders.

But it was Dow, with his position at Pratt Institute, who would prove to be most influential. It was at his urging that two of his students, Zulma Steele and Edna Walker, accepted the Whiteheads’ invitation. These two women, 1903 Pratt graduates with degrees in drawing, painting, and composition, were to become collaborators in art, crafts, design, and life. With the guidance of the Whiteheads, their combined talents soon began to influence the Byrdcliffe style. Of the two women, though, it was Zulma who became Byrdcliffe’s unofficial lead designer. It was Zulma’s hand that put the fleurde-lis, Ralph Whitehead’s chosen image for Byrdcliffe, to paper, creating a symbol that is used to this day. Her design of and location choice for Angelus, the cottage in which she and Edna would live, attest to her position at Byrdcliffe. The house was built at the highest elevation of any Byrdcliffe structure, including the Whiteheads’ home, White Pines.

Over the next twenty summers, Zulma continued her artistic practice at Byrdcliffe. Her winters were spent on lower Lexington Avenue in the New York City apartment and studio she shared with Walker. Zulma’s time at Byrdcliffe ended in 1926, when she married Nielson Parker, but her creativity continued as she explored other crafts, including ceramics, which resulted in the creation of Zedware, Zulma and Edna’s line of pottery.

In November 1938, more than a decade after she left the colony, Zulma’s influence on Byrdcliffe re-emerged splendidly. In that month and year, the first exhibition of crafts created by women was held at what is now the Woodstock Artists Association and Museum. Among those showing were Mary DuFresne, Mabel Chase, Florence Webster, Louise Lindin—and Zulma Steele Parker. This exhibition was well received, and it served to empower the women to organize the Woodstock Guild of Craftsman in 1939. Its first chairperson, not surprisingly, was Zulma Steele Parker.

In 1975, Byrdcliffe was bequeathed by Peter Whitehead, Ralph and Jane’s son, to the Woodstock Guild of Craftsman. Unfortunately, Zulma, who died in 1979, did not live to share in the pleasure of the rebirth of her two creative endeavors into the organization we now know as the Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild. This catalogue and exhibition are a celebration of the 81st anniversary of the founding of the Woodstock Guild of Craftsman and are a long-overdue tribute to Zulma Steele: Artist/Craftswoman.

This is the first retrospective exhibition and the first publication devoted to Zulma Steele, a multitalented artist who made art in many media over a long career. She worked as a serious painter and printmaker, as well as in many crafts, including furniture design, ceramics, textiles, and frame making. Over her career Steele was a world traveler and a central figure in the art colony of Woodstock, New York, where she lived for most of her life. To those who knew her she was elegant and reticent. Indeed, she left little autobiographical information and few written records, so her story must be stitched together from bits and pieces—and from the insights afforded by her art.

Zulma Steele came from an illustrious family, who played a large role in her life. Her maternal ancestors, the Dorrs, were active in the China trade and intermarried with the Ripleys of Vermont, who were descended in part from eighteenth–century French colonists of Haiti. Steele’s middle name was Ripley. Ancestors on her paternal side included the Livingstons, who owned vast properties in New York. During the late nineteenth-century “rent wars” in that state, the Dorrs sided with the tenants against the lordly Livingstons. “It is interesting that on Father’s side there were the Livingstons and on Mother’s side the Down Renters,” Steele wrote to a relative.1

Steele’s immediate family was artistic, including her grandmother, Julia Dorr, a poet, and her mother, Zulma

DeLacy Steele, an artist who specialized in landscape painting. Her brother, Frederick Dorr Steele, was a successful illustrator, today most famous for popularizing the classic image of the detective Sherlock Holmes, with his Meerschaum pipe and deerstalker hat, in illustrations of Arthur Conan Doyle’s mystery stories.

Zulma was born in 1881 in Wisconsin, month and day unrecorded. When she was seven, her family moved to Vermont and then to New York. At nineteen she began art classes at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and studied as well at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Boston Museum School. She received her degree from Pratt in 1903, having worked most extensively with the influential artist and teacher Arthur Wesley Dow, known for his sensitive landscape paintings and for being among the early popularizers of Japanese aesthetics in the United States. In Dow’s class, she met fellow student Edna Walker, who would be her companion for close to twenty years. At Pratt, Steele and Walker became acquainted with the artist Bolton Brown, who was then in the process of establishing the Byrdcliffe arts and crafts colony in Woodstock. He invited them there as scholarship artists, introducing Steele to the region of upstate New York that would be her home for the rest of her active life.

Brown was one of the founders of Byrdcliffe, along with the bohemian poet Hervey White, both of whom had been hired by Englishman Ralph Radcliffe Whitehead, who

sponsored the colony and bankrolled it.2 Scion of a family that ran profitable textile mills in Staffordshire, Whitehead studied at Oxford with the brilliant philosopher of the Arts and Crafts movement John Ruskin, who hated England’s industrial revolution and its polluting, dehumanizing factories—the very source of the Whitehead family wealth. Whitehead married Jane Byrd McCall, an artist from Philadelphia, and moved to the United States, where he put his inherited fortune to work in an attempt to realize Ruskin’s ideal of a colony where both fine art and crafts would be practiced by a community of kindred spirits. Ruskin recommended that this should happen in some beautiful natural setting distant from the crowded and befouled big cities. In 1902, with the assistance of Brown and White, Whitehead purchased around 1200 acres on the side of a mountain overlooking the village of Woodstock, where he erected thirty buildings, and invited artists and craftspeople to live and work in them. Steele and Walker were among his first scholarship students, and they designed much of the distinctive Arts and Crafts furniture that was manufactured at the colony.

Byrdcliffe furniture, discussed in greater detail in Derin Tanyol’s essay in this publication, was supposed to support the colony through sales. But because Byrdcliffe adhered to Arts and Crafts values opposed to machine production, the furniture was labor-intensive and expensive to produce. It could not compete commercially

with the less costly pieces manufactured, with the aid of machinery, by rival enterprises such as Stickley and Roycroft. Consequently, Byrdcliffe furniture is rare and much sought-after today.

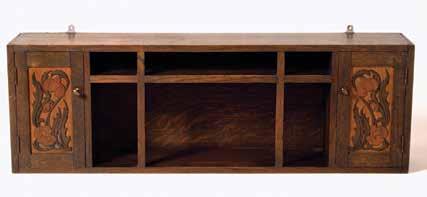

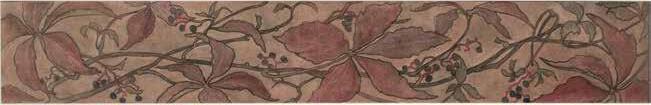

Most of it was designed by Steele and Walker and overseen by Whitehead, who had apprenticed with a carpenter in Germany for a year before coming to the United States. The furniture is classic Arts and Crafts, made of local wood, its grain exposed to express its origins in nature (figs. 1 and 2). The contours are austere and rectilinear, in homage to the Arts and Crafts ideals of simplicity and truth-to-materials. Flat wooden panels are complemented by bursts of decorative imagery, usually drawn by Steele and Walker. While she was in England, Jane Whitehead had sketched plants side by side with Ruskin, and Whitehead personally knew William Morris, the other great representative of the Arts and Crafts in England. Both Whiteheads, then, provided direct connections to the origins of the movement. Steele and Walker followed Ruskin’s and Dow’s precepts, sketching plants from nature in delicately precise botanical drawings. They transformed these drawings into designs for the rectilinear panels of the furniture, which were next traced onto the wood panels, and then carved in relief by Byrdcliffe’s woodworkers. Finally the panels were stained in delicate tints that complemented the warm colors of the surrounding wooden rectangles (figs. 3 and 4).3

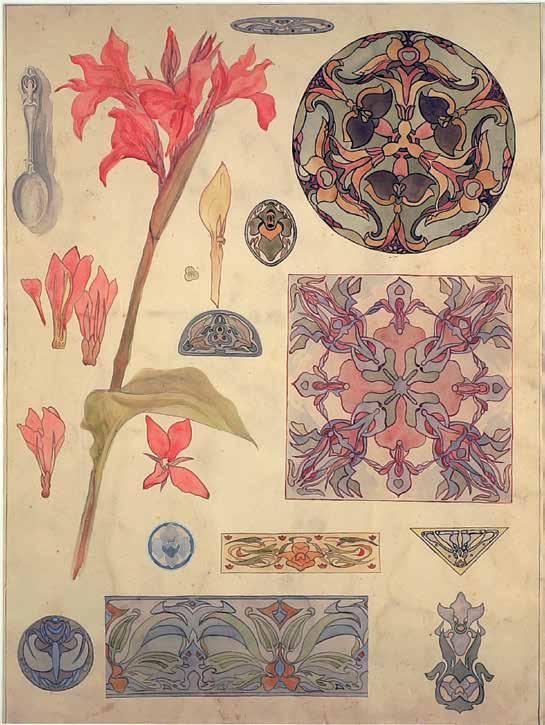

The first painting teacher at Byrdcliffe, Hermann Dudley Murphy, started an influential frame-making business in Boston, Carrig-Rohane, and Steele and Walker learned the craft from him.4 Steele later said, “The frame making we had at Byrdcliffe was the only craft we had that paid a profit.”5 A drawing for two mirror frames carries the names of both Steele and Walker. Within the narrow bands of the frame parallel straight lines are contrasted with passages of curvilinear botanical ornament (fig. 5). They also designed textiles. Steele’s drawing for a wallpaper pattern or a fabric reveals a sinuous quality that is more Art Nouveau than William Morris (fig. 6). In 1907 Steele exhibited a kimono with an oat pattern and a screen ornamented with flowers at the Society of Arts and Crafts exhibition in Boston, in the company of works by several other Byrdcliffe craftspeople.6

Steele embodied the Arts and Crafts ideal that crafts are equal in status to the fine arts. She likely designed the house Whitehead built for her and Walker, which still stands on Byrdcliffe property. All Byrdcliffe houses had names, which sometimes were the product of long discussions. The Steele-Walker house was “Angelus.”

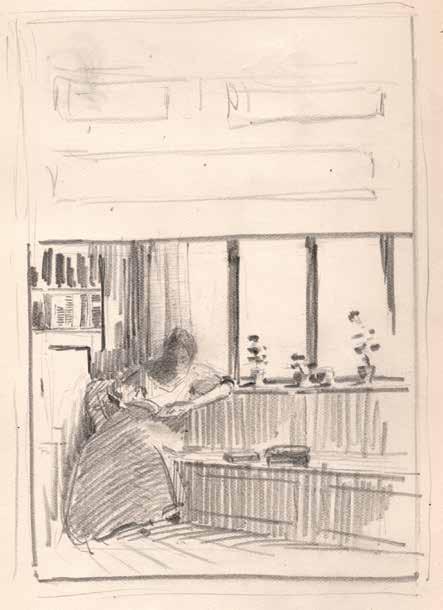

A quick drawing in one of Steele’s sketchbooks depicting a woman, probably Walker, reading on a built-in bench, conveys the relaxed domesticity and intimacy with nature that characterized the two women’s lives at Byrdcliffe (fig. 7). While Angelus was being built, Steele lived with veteran painter Birge Harrison and his wife, the Whiteheads having brought Harrison to Byrdcliffe as a painting instructor. Harrison, who spent years in France and who had lived in French art colonies, was a highly accomplished landscape painter in the Tonalist mode, a style derived from Impressionism but favoring more restrained colors that convey moods of reverie and nostalgia. Steele became a close friend of the Harrisons and studied painting with the respected teacher.

Like her mother, Steele painted landscapes, and she was one of the first women to ambitiously practice landscape painting. Landscape was one of the era’s most progressive subjects for art, and in 1906 the Art Students League in New York City created a summer school in Woodstock devoted to it, with Harrison as its instructor.

Steele’s early ventures into landscape resulted in vistas with delicately muted tonalities reflecting her mentor’s style. Summer , a hazy landscape from 1904, features a compositional strategy to which Steele returned repeatedly over the course of her career: a diagonal wedge of land introduces the foreground, serving as a repoussoir for succeeding layers that recede into a misty distance (fig. 8). The foreground is inhabited by four relaxed figures, a young man facing three reclining women in long white dresses. This mirrors the gender imbalance at Byrdcliffe, where many of the artists and craftspeople for whom Whitehead generously provided living and working spaces were young women looking to break with stereotypes and become independent practitioners of their art. Whitehead had originally been introduced to his collaborator, Hervey White, by the renowned feminist writer (“The Yellow Wallpaper”), Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Gilman was an early resident and frequent guest at the colony, as were other women with independent minds and artistic aspirations.

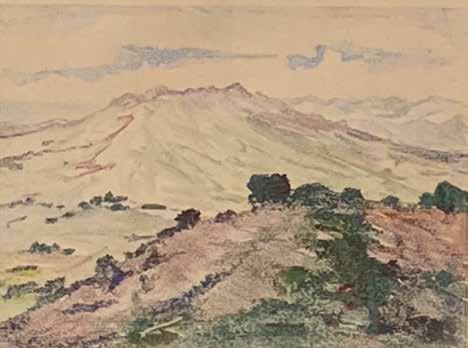

Soon, Steele began to brighten the muted, evocative palette she had used in Summer and her paint handling became more aggressive. This reflected the progressive movements prevalent at the time and evident at Woodstock’s own Sunflower Club, which included modernist (and Harrison student) Andrew Dasburg, who in the early 1910s experimented with Cubism and—briefly—total abstraction. Such Steele paintings as Untitled (Neo-Impressionist Landscape) depict deep Hudson River Valley vistas rendered with thick dabs of bright color, suggesting an aggressive version of late nineteenth century French Pointillism (fig. 9). The painting is another example of Steele’s use of repoussoir, here in the compositional device of angling a plane into the canvas from the edge to establish a foreground beyond which the rest of the landscape moves into space.

The construction of the Ashokan Reservoir in the mid-1910s inspired Steele’s most ambitious series of landscape paintings, more extensively discussed by Bruce Weber in his essay in this publication (figs. 10 and 11). These expansive views, with glistening bodies of water

leading to glowing distant mountains, represent a modern evolution from nineteenth-century Hudson River School paintings, descending from that movement’s founder, Thomas Cole, which often included peaceful bodies of water. Steele’s deep vistas, however, featuring her newly liberated use of color, have as their subject not nature’s splendor, but a work of human technology, a reservoir. The building of this vast artificial lake, constructed to supply water to New York City almost a hundred miles to the south, displaced some two thousand residents in the process of being built. Steele’s luminous scenes document the filling of the reservoir with water but avoid any attendant social issues.

In the mid-1910s, Steele exhibited her paintings frequently. It was not unusual for Woodstock artists to have residences in New York City as well as upstate—proximity to the metropolis was an argument for choosing Woodstock as the site for Byrdcliffe in the first place—and several Manhattan addresses have been found for Steele and Walker.7

In 1914 Steele showed in an exhibition at the National Arts Club, which included many of the most avant-garde artists

in the United States at the time. She also exhibited twice that year at the progressive MacDowell Club, showing her Ashokan paintings in March, after exhibiting five landscape paintings there in January in a show of twelve women artists. Participating in a show of all women artists was typical for her. An active member of the Association of Women Painters and Sculptors, in 1915 she showed two landscape paintings at the Macbeth Gallery in an exhibition of works by ninety-nine women artists to benefit women’s suffrage, taking her stand for women’s right to vote.

In 1915 some of her works were exhibited at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. Steele loved to travel, mostly during the winters to places with warmer climates, including Italy, the Bahamas, and Puerto Rico. Ireland was another of her destinations. The paintings that came after the Ashokan series rarely approached these works in size and grandeur, but she continued her interest in landscape subjects by making small, loosely painted but nevertheless specific landscape views. These included Woodstock scenes, some thickly painted snowscapes among them (fig. 12). Steele stayed with an aunt in Italy in 1912.8 A view of a rural Italian town, painted on canvas board, includes poplars at the right that establish the foreground, while dabs of paint

represent white buildings with their orange roofs in the valley below, in front of a range of pale blue mountains in the background (fig. 13).

Around this time Steele drew a striking self-portrait in line. She contemplatively rests her head on her hand, most likely regarding herself in a mirror (fig. 14). It is an image

of self-appraisal, suggesting a mature self-knowledge, in contrast to her mysterious Tonalist Self-Portrait, from 1901, when she was studying with Dow (fig.15). In that earlier work, she is seen in three-quarter view, all but engulfed by the shadows that surround her on all sides as a few areas of dim light bring her features out of the moody darkness.

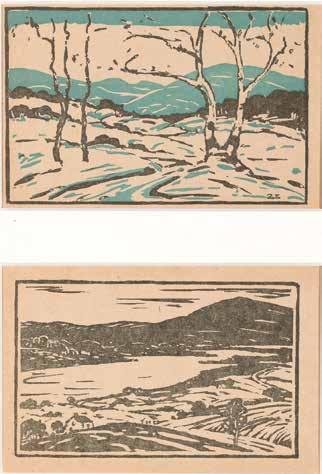

In the later 1910s Steele exercised her passion for landscape in a medium new to her, monotype, in which a one-of-a-kind work is painted on a hard surface and then run through a press to print the image on a piece of paper. She made a series of small radiant landscapes, the white paper she used providing their luminosity. Some were memories of her winter travels, such as the horizontal composition of palm trees in front of a calm body of water, with a verdant band of greenery at the bottom (fig. 16). Another favored theme was mountains rising into the sky above the terrain below (fig. 17). The small sizes of these prints contrast with the grandeur of the scenes depicted, as barren mountainsides provide fields for plays of delicate color. A tiny but especially glowing monotype of a slender coastline at sunset, mirrored in placid water, puts Steele among some “realist” painters of the time who presented easily recognizable scenes as flat color fields, approaching abstraction (fig. 18). The tendency is found in some of Birge Harrison’s paintings as well. Steele also made monochrome monotypes in warm browns or blacks, including a view of White Pines, the residence of the Whiteheads, which still presides over the Byrdcliffe landscape today (fig. 19). This is one of her rare dated works, from 1916. Steele made her monotypes a few years after the New York Armory Show of 1913, which introduced the American art public to radical European modernism. In 1918

she published an unusual linoleum print in The Plowshare magazine, which demonstrates her emerging interest in abstraction (fig. 20). The Plowshare was founded and printed by Hervey White who, soon tiring of life under Whitehead’s rule at Byrdcliffe, left, managed to buy a mountainside just outside of Woodstock proper, and

there created his own art colony. “The Maverick,” aptly named, was a low-budget alternative to Whitehead’s more refined community.9 Steele’s appearance in a Maverick publication is an example of how social lines in the Woodstock art community interpenetrated despite differing lifestyles. Another example of this was the founding of the Woodstock Artists Association in 1919, which again brought together various factions of Woodstock’s artistic community in a common purpose; Steele was a charter member. In 1939 she went on to become the first president of the Woodstock Guild of Craftsmen, which in 1975 inherited Byrdcliffe from Whitehead’s son, Peter, and is the organization hosting this exhibition.

Steele’s linoleum print in The Plowshare suffered the fate of quite a few examples of early experiments in abstraction—and some current ones as well It was reproduced sideways, as is made evident by her monogram in the lower right corner. A dramatic blackand-white composition of pointed, curving shapes, it introduces White’s novel, The Prodigal Father , a story about a young clergyman whose father abandoned him at an early age, only to return to the town where the son was beginning to practice his ministry. One of White’s most compelling pieces of writing, based on the Woodstock scene and the tensions between the older residents and the artist newcomers, it exists only in serial, as chapters in the magazine, and has never been republished. When Steele’s print is correctly oriented, as it is here, its relevance to White’s story becomes clear. The artist created an abstracted version of traditional depictions of the biblical subject of The Prodigal Son, with a figure near the center kneeling and bowing in repentance to another figure seated higher up to the left. This near-abstraction, with figures almost obscured by pure forms but recognizable after closer examination, is a type of imagery to which the artist returned later in her career.

In 1918 Zulma Steele boldly left the United States to serve with the American Red Cross in France during the final year of World War I; a photograph shows her standing proudly upright in her uniform (fig. 21). As Tad Wise discovered, Edna Walker also served with the Red Cross in France at the same time.10 After working for a year in

a hospital, and with the Armistice having ended, Steele obtained permission to visit artillery-ravaged Verdun, where she made small paintings on the backs of cigar boxes, none of which have been located.11

After she returned to the United States, Steele embarked on a new artistic pursuit, ceramics. Sketchbooks in the collection of her descendants show that she studied traditional pottery by making drawings of vessels from sources that include ancient Egypt, Persia, and the Italian Renaissance. She developed her own unusual forms, favoring warm yellow or brown glazes, or bright blue ones. One simple brown bowl is enlivened by a thick scrolling floriate design around the rim, echoing the decorative botanical patterns she and Walker made for Byrdcliffe furniture (fig. 22). A turquoise urn is dramatically suspended on three pretzel-shaped feet turned

upright, while a small turquoise double-handled cup is enlivened with a dark blue glaze dripping down from its rim, reminiscent of the painterly glazes found in some East Asian ceramics (figs. 23 and 24). In 1922, she showed her ceramics at the Woodstock Artists Association, along with her paintings.12 She made these pots at Byrdcliffe, continuing the ceramic tradition previously practiced there by Elizabeth Hardenburgh and Edith Penman, another Byrdcliffe craftswomen couple, who stopped making the ceramics they called “Byrdcliffe Pottery” in 1922 or 1923. Subsequently, Steele took over their facilities; a photograph shows her working on a kick wheel there (fig. 25). About this time she also moved out of Angelus to a house just west of Byrdcliffe. Little is known about the circumstances surrounding her move.

Steele named her ceramics Zedware, which Tad Wise ingeniously suggests merges her first name with Walker’s.13 There has been speculation about the relationship between Steele and Walker, recently spurred by Wise’s two-part article about Steele in the Woodstock Times in which he describes their “life-long love affair” and claims Steele was bisexual.14 There is no doubt that Steele and Walker were close, living together for almost twenty years. A quick drawing in one of Steele’s sketchbooks is a testament to their connectedness. It depicts two women

from the back, carrying four suitcases, two each, one monogrammed “ZS” and the other “EMW,” as if their identities were interchangeable (fig. 26). A photograph in a family album depicts the two women seated on steps of a house with Steele’s mother and father standing above them, indicating that their relationship was accepted, at least on some level, by her parents.15

Anita Smith, who wrote the first history of Woodstock, included an anecdote in which Rosie McGee, a local caretaker who had a habit of watching her neighbors through a spyglass, was surprised to see Zulma Steele in the company of a man—but when she walked up to investigate “she found the man was Edna Walker working in pants.”16 There was quite a bit of tolerance for gender fluidity among the artists of the colony, and many people believed that Steele had a romantic

relationship with her patron, Ralph Whitehead. In an angry letter, Jane Whitehead wrote to her husband, “I found the situation at home all summer disagreeable, and at last I came away and left it.… Do you remember that you and Miss Steele had given rise to talk all summer, and no one had said a word.”17 Historian Alf Evers recalled that when he interviewed Steele, “she was very noticeably shy about Ralph Whitehead.”18 Then, in 1926, Zulma Steele married Neilson Parker, a gentleman farmer who was wealthy from his insurance business. Earlier Jane Whitehead commented cattily in a letter to her son, “By the way, that old duffer, Ne[i]lson Parker, you remember—he’s very attentive to Miss Steele. I do hope she’ll be his 3rd wife.”19

Since the early 1910s Walker had practiced her talents at textile design by working for the prestigious Herter Looms in New York City. Many believed that when Zulma married, Edna Walker moved away and was never heard from again, but Alf Evers claimed that she married a Scotsman and moved to Scotland.20 In any case, forty-five-year-old Steele went from bride to widow in just two years, as Parker passed away in 1928, leaving her with the house they named “Green Pastures” on a large estate that years before had been owned by her Livingston ancestors.21

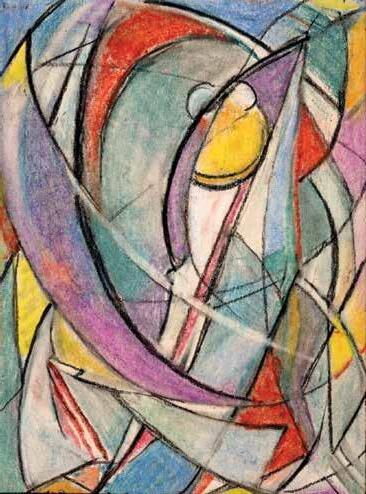

After she was widowed Steele resumed her travels. Some years after her Red Cross experience in France she returned to Paris, where she studied with the progressive Cubist painter André L’Hote. The experience encouraged her to develop her painting in a more modernist direction. She also became increasingly interested in her genealogy, and while in Paris did research about the extensive cotton and indigo plantations in Haiti that the Ripley branch of her family owned in the eighteenth century. She made four or five trips to Haiti in the late 1940s and 1950s, seeking to identify her family’s properties, which were confiscated after the independence uprisings of the late eighteenth century. After she convinced the locals that she was not there to try to reclaim any real estate, they became hospitable, helping her travel through many parts of the country where she witnessed regional customs, including voodoo rites. These ceremonies probably inspired her intense small pastel drawing in her Cubist style (fig. 27) It is dominated by the head of a witch doc-

tor, who emits light rays and is surrounded by an audience of fragmented heads and geometrical lines.

Another of Steele’s Haitian-themed paintings centers on a mother and child, a recurrent motif in her drawings over the years and a traditional image of female identity (fig. 28). Here an abstract curving line sweeps across the center of the composition, animating a scene of a mother multitasking: holding a baby while reaching into a bowl in a crowded outdoor marketplace, with a pile of yellow fruit below her. She is surrounded by dark-skinned figures. We could dismiss this work as a touristic or even colonialist painting—but how many women in their seventies were making paintings of Haitian street scenes?

In contrast to her anthropological or exoticist works inspired by rituals and marketplaces is a charming pastel of a fashionably dressed young dark-skinned woman in front of the window of a clothing store (fig. 29). The specifics of this composition are unknown, but the piece suggests an urban realist Manhattan 14th Street scene transposed to Haiti. Throughout her career, Steele sketched street life, in New York City as well as in foreign countries, few of these works titled or dated. She depicted milieus easily accessible to an urban wanderer, a flaneur, including outdoor market scenes, children playing in the street, and mothers with children. The subjects, whether in her early realist style or in her later abstracted mode, relate to the urban scene painters of the Ash Can

School and their followers. Here again Steele had a family connection. Her brother’s daughter married the son of painter Frederick Dana Marsh. Among his several residences was a house in Woodstock, and he was the father of Reginald Marsh, a leading figure among the urban realists. Steele knew both the father and the son.22

Another group of Steele’s paintings and works on paper appear totally abstract. Some retain the vestiges of imagery, while others are nonreferential. None of them is dated, so the only way to locate them within the arc of the artist’s career is through informed guesswork. Clearly, they come after her exposure to L’Hote, but whether they predate or postdate the Haitian paintings, or are contemporary with them, is at present unknown.

Steele addressed the issue of abstract art in her onepage biographical statement:

The experiences of war and some knowledge of other civilizations, of speed and air flight, have made earlier art expression less adequate. After all, if you really have been over the rainbow and looked down at the floor of the ocean, your point of view changes…23

A small work on paper with bright colors, scimitarlike forms, and free-floating lines seems completely abstract, but, in another, figures appear to be embedded, reminiscent of the Prodigal Father print from 1915 (figs. 30 and 31). A dynamic three-foot-wide painting on canvas looks like an elegant abstraction (fig. 32). But could this be a subliminal Leda and the Swan, the swan’s two white wings rising up to the right, and its long neck merging with the white body of a woman who reclines above it? Impossible to know at this point in our research, but it is a tantalizing prospect—typical of the mystery that characterizes much of Zulma Steele’s life and art.

Throughout her later years Steele continued to paint and to travel. In 1954 she converted a shed on her property into an art gallery where, at the end of the summer, she held what a newspaper at the time called “a one-man show.” 24 Four years later, in 1958, she worked with an art advisor to organize an exhibition of her paintings to travel to about a dozen libraries and college art galleries. The tour was interrupted by a fire in the library of St. Frances University, Loretto, Pennsylvania, which destroyed a group of her works. Undaunted, the artist set about making new paintings to replace them.

Her late years at Green Pastures were devoted to making her art, participating in the active art world of Woodstock, and enjoying her home. There she lived with her artworks and ample studio space, amid furnishings that included a set of Federal-style chairs, now in the Columbia County Historical Society, and three paintings of her Dorr ancestors attributed to the esteemed folk artist Ami Phillips, which are now in the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center.25 In 1967, at age eighty-six, Steele moved into a nursing home in New Jersey, where she passed away in 1979.

Tram Coombs wrote of Zulma Steele, “Despite her long life in Woodstock, little is known about her….” 26

Bolton Brown remembered her from the first days at Byrdcliffe as “really our outstanding lady, both visually and in a quality we may call style.” 27 Alf Evers recounted,

I questioned her without getting very far…she was very unusual, had great dignity when she was old…and very erect, you know…she could have been a person on the upper levels of society…she took herself very seriously and everybody else took her very seriously…I would have tea with her, old-fashioned tea, and we would chat but when we would get to the past she would veer away…28

We hope this project brings some visibility to this bold and talented artist and her multi-faceted work, as we present the first exhibition and publication devoted to Zulma Steele.

1 Zulma Steele to Robert Steele, November 3, 1958, copy in the author’s collection. This publication is being written and produced during the period of lockdown because of the Covid-19 pandemic, so some specifics of research are unavailable as libraries and archives are closed.

2 For Byrdcliffe, see Nancy Greene ed., Byrdcliffe, An American Arts and Crafts Colony (Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, 2004).

3 Robert W. Lang, in his informative Shop Drawings for Byrdcliffe Furniture (Cincinnati: RWD Publishing, 2020), 25, persuasively suggests influences from Alvin Crocker Nye, who taught furniture making at Pratt while Steele and Walker studied there, and from Nye’s book, Furniture Designing and Draughting. Lang also points out that there was some machinery in the Bottega, Byrdcliffe’s woodworking shop, 24

4 Bertha Thompson, “The Craftsmen of Byrdcliffe,” Publications of the Woodstock Historical Society, no. 10 (July 1933), 10.

5 Edward Sanders, “Interview with Alf Evers,” Woodstock Journal (June 28, 1996). Thanks to Ed Sanders for sending me this reference.

6 Robert Edwards, The Byrdcliffe Arts and Crafts Colony: Life by Design (Delaware Art Museum, 1984).

7 The drawing of the frame includes the address 158 W. 23rd Street for the two of them. Other sources mention an address on Lexington Avenue, and 215 West 13th.

8 In a letter to his wife dated October 10, 1912, Ralph Whitehead wrote, “Miss Walker looks very ill and Miss Quinn and I are trying to persuade her to take the holiday which Herter has promised her to go to Italy in November and

join Miss Steele who is staying with an aunt living there.” The suggestion may have succeeded because in a letter from May 9, 1914, he wrote, “Miss Thompson [a metal worker at Byrdcliffe] & Miss Walker & Miss Steele are here now. They have all been away for some time.” Winterthur Papers, Downs Collection, Folder 8, Box 2, Folder 1, Box 4.

9 For The Maverick, see Josephine Bloodgood and Tom Wolf, The Maverick: Hervey White’s Colony of the Arts with essays by William G. Rhoades and Tom Wolf (Woodstock Artists Association and Museum, 2006).

10 Tad Wise, “Gender Blending in Early Woodstock and Our First Female Genius,” Woodstock Times (August 26, 2018) and “Zulma Steele, Gender Blender Extraordinaire,” Woodstock Times (September 5, 2018), reproduces a photograph he discovered that seems to be of the two artists in the Red Cross, and there is a photograph of Walker with the Red Cross in France in 1920 in the Library of Congress. A Steele sketchbook in the collection of her family includes a series of portrait sketches that could well have been made on an ocean voyage, with several of the same muffled-up woman and one of a woman sleeping, all of which could be Walker.

11 Steele statement, n.d., copy in Archives, Woodstock Artists Association. This one-page, typed document is her only known autobiographical statement or resume. Zulma Steele files, Archives, Woodstock Artists Association.

12 Marinobel Smith, “At Woodstock,” described Steele’s ceramics at the Artists Association: “some in brilliant colors, some decorated with copper and silver glaze in Spanish patterns.” Unidentified newspaper clipping (August 1922), WAA clippings book, Woodstock Artists Association Archives.

13 Tad Wise, articles cited in note 10. When advertised at the time, Zedware pottery was described as “Made by Zulma Steele, Woodstock, New York.”

14 Tad Wise, articles cited in note 10. Wise’s articles contribute valuable insights and information to the story of Zulma Steele, but at times they are speculative. Several of his arguments are based on the tricky practice of identifying people in photographs that are over a hundred years old, and here he undermines his credibility by stating a photograph of Zulma and Edna seated facing each other at Angelus is misidentified—that the handwritten names below are wrong, and Zulma is actually Edna and vice versa. But he gives no evidence, and the photo is from a family album, so he is asking the reader to believe that he can recognize Zulma in a photograph more accurately than her own relatives could. The album was owned by the late family historian Robert Steele. According to Tom Hunt, a descendant of Zulma Steele, it is still with a family member in California, and Hunt also has photocopies of it. In the years around 1950 Steele traveled repeatedly to Caribbean islands. She made several pastel drawings of “native” women, and on occasion men, embracing, which suggests that her interest in same sex relationships was ongoing.

15 I discuss this album in note 14.

16 Anita Smith, Woodstock, History and Hearsay (Woodstock, NY: Woodstock Arts, 1959; reprint ed., 2006), 124.

17 Jane Whitehead, Letter to Ralph Whitehead, November 4, no year, Winterthur Papers, DownsCollection. Box 7.

18 Edward Sanders, “Interview with Alf Evers,” Woodstock Journal (June 28, 1996). My thanks to Ed Sanders for sending me this reference.

19 Jane Whitehead, Letter to Bim (Ralph Whitehead Jr.), July 11 and 13, 1924, Winterthur Papers, Downs Collection, Folder 11, Box 7.

20 Alf Evers interview with Tom Wolf, July 23, 2003.

21 Estimates about the extent of the property of the Green Pastures estate vary widely. Tram Coombs, in “Delicacies of Steele at the Paradox,” Woodstock Times (July 15, 1982), cites 300 acres, a figure that appears elsewhere. Tinker Twine in “Green Pastures No More,” Woodstock Times (November 16, 1989), writes 45 acres, but points out that “Much of the land borders a town-owned greenbelt along the Sawkill Creek at Big Deep which [Zulma] Parker had bequeathed to the town” (13).

22 Tom Hunt, the Steele relative who has been very helpful with this exhibition and essay, affirms that Zulma knew both Frederick and Reginald Marsh.

23 Steele statement (document cited in note 11) , n.d., copy in Archives, Woodstock Artists Association.

24 “Zulma Parker Has One-Man Show In Her Own Gallery,” unidentified newspaper clipping. WAA clippings book, Archives, Woodstock Artists Association.

25 My thanks to historian Ruth Piwonka for this information.

26 Tram Coombs, in “Delicacies of Steele at the Paradox,” Woodstock Times (July 15, 1982).

27 Bolton Brown, “Early Days at Woodstock,” Publications of the Woodstock Historical Society, XIII (August-September 1937), 13.

28 Beate Dumont, transcript of an interview with Alf Evers, February 17, 1995, part of her Senior Project in Art History at Bard College, collection of Tom Wolf.

An elegant oak chiffonier (fig. 1) with door inserts painted by Hermann Dudley Murphy is one of the most frequently reproduced objects created at the Byrdcliffe Art Colony, which manufactured furniture from late 1903 to the summer of 1905.1 A modular design used in several extant examples,2 the chest illustrates Byrdcliffe’s distinctive take on the Arts and Crafts style. Its sturdy minimalism, fully rectilinear composition, and refusal of intricate turnings and other nonfunctional decorative components define the economy of craftsmanship of the movement. Equally emblematic of Byrdcliffe’s design language are the chiffonier’s painted doors. Most of the Byrdcliffe chests, drop-front desks, and linen presses (storage units with drawers and doors used before built-in closets were standard)3 feature painted or carved panel inserts on their faces. Byrdcliffe ornamentation is sourced predominantly from local plant life or, as here, landscape, reveling in the organic splendor that seduced Byrdcliffe founders Ralph and Jane Whitehead and other colony residents to go make art on a mountaintop in Woodstock, New York.

Yet the pictorial style of Murphy’s painted doors represents neither Byrdcliffe’s most prevalent decorative idiom nor typical Arts and Crafts design. It was painter, printmaker, and designer Zulma Steele (1881–1979) who would most fully establish Byrdcliffe’s decorative vocabulary, her furniture designs defining the colony’s

response to the Arts and Crafts movement. Indeed, Murphy’s dreamy Tonalist landscape of a river receding into the distance is anathema to Arts and Crafts aesthetics in its perspectival conviction. The leading man of the Arts and Crafts movement, William Morris (1834–1896), was an English designer of textiles, wallpaper, and furniture whose teachings helped the Whiteheads envision their Arts and Crafts colony, and whose furnishings decorated their homes.4 Morris had a lot to say about the weary disappointment induced by works of art that took direct replication of nature and three-dimensional space as their points of departure. Renowned for his wallpaper designs in which stylized flowers, vines, leaves, and birds conjoin into energetic all-over patterns (figs. 2 and 3), Morris called for decorating “with ornament that reminds us of the outward face of the earth . . . I say, with ornament that reminds us of these things . . . because scientific representation of them would again involve us in the problems of hard fact and the troubles of life.”5

Ralph Whitehead echoed this sentiment in his book of essays, Grass of the Desert (1892), writing that art “has conventions, a special language through which it must speak . . . [P]ainting is no more the simple imitation of the exterior of natural objects than music is the imitation of natural sounds.”6 Through clarity of suggestion and solid design principles instead of what Morris considered “toilsome” mimesis, nature could be, and should

be, beautifully conventionalized. Used by thinkers and critics including Whitehead, Morris, and their eminent intellectual guide John Ruskin, the term “conventionalized” is what we today call “stylized.” Conventionalization underlined the conviction that, simply put, art itself was the point of art, with the pleasure and comfort that its creation brought both to maker and user nevertheless tendering dramatic possibilities for social change.7

Zulma Steele left us nothing in the way of writings on art—or on any subject, for that matter—but her “conventionalized” designs demonstrate a studied adherence to the aesthetic prescriptions of William Morris. She arrived in Woodstock when Byrdcliffe first opened its doors to artists in 1903. Steele and her collaborator and probable partner Edna Walker8 came to explore Byrdcliffe on the recommendation of painter and printmaker Arthur Wesley Dow, with whom they both studied at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn.9 While artists like Hermann Dudley Murphy and Birge Harrison lived and worked at Byrdcliffe only briefly,10 Steele was in it for the long haul, returning as a summer resident regularly (with gaps for travel to Europe, Haiti, and Puerto Rico)11 until the mid-1920s, with Walker joining her for many of those sojourns. Steele created paintings, prints in different media, and textiles and ceramics, but she spent her first year at Byrdcliffe mostly making furniture designs.

Furniture production at the colony was a collaborative process, in which designers like Steele and Walker would create drawings of decorative elements for various furniture prototypes. Upon Whitehead’s approval12 the designs were executed in the woodshop, a building called the Bottega, which burned down in 197813 Whitehead

had studied cabinet-making in Europe14 but, as with all his creative endeavors, he was more enchanted learner than adroit craftsman. For the craftsman requirement, he enlisted Fordyce Herrick as foreman of the woodshop, with Nordic cabinet makers Olaf Westerling and Riulf Erlenson also on the rolls.15 Jane Whitehead sometimes participated in production by applying stains to completed furnishings. She was known to be critical of others’ finishing techniques and sometimes required pieces to be sanded down to the natural wood and stained all over again.16

Steele’s decorating schemes for desks, tables, chairs, sideboards, and more, which date to about 1904, include signature botanical motifs—such local flora as lilies, woodbine, and irises—that walk the conventionalized line between naturalism and abstraction. Her ink and watercolor woodbine design (fig. 4), for a painted frieze on a desk at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art,17 abounds with leaves—realistic in their subtle veins and crimped edges, yet stylized in their sharply delineated contours filled with color. These dark outlines are reminiscent of both Japanese printmaking and Morris, who wrote that “definite form bounded by firm outlines is a necessity for all ornament”18 (see, for example, his Acanthus wallpaper, fig. 2).

Steele’s leaves are the rich reddish-brown of autumn, the season when clusters of woodbine berries, which punctuate the design at regular intervals, come to maturity. Like the botanical studies by Steele in the permanent collection of the Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild,19 the woodbine in the desk design translates into an immediately recognizable plant, more imitative than elements in Morris’s wallpaper, for example. Yet the woodbine water-

color is attendant more to decorative design principles than to naturalism. In an all-over composition anchored at left, center, and right by three larger leaf clusters, the woodbine is connected by a network of vine tendrils that perform the same structural function as the wooden trellis in Morris’s wallpaper (fig. 3), flattening the motifs within a restricted vertical space that is connected and compressed laterally. Equally in keeping with Arts and Crafts tactics for repressing three dimensionality, Steele’s woodbine casts no shadows, whether on itself or on its surroundings. Morris impatiently described the artlessness of spatial realism in mainstream Victorian wallpaper as “sham-real boughs and flowers, casting sham-real shadows on your walls.”20

A second of Steele’s woodbine watercolors (fig. 5) is an example of a decorative system unique to Byrdcliffe furniture, in which two or three painted or carved panels, recessed into doors, give the illusion of a continuous narrative—whether of botanical elements or, in the case of Murphy’s chiffonier (fig. 1), a river—between and behind the undecorated parts of the furniture.21 The illusion in the Murphy is of a distant river viewed through two windows side by side. In Steele’s woodbine triptych, however, the rectangular “windows” enclose a two-dimensional surface design rather than a view into space. A branch of woodbine moves upward diagonally from the

lower right, disappears behind a wooden stile stained red, reemerges at center, and disappears again before terminating at a cluster of berries in the left panel. The naturalism of the plant is underlined by its “living” behind the vertical dividers, only to be dominated by stylization in its flat background and absence of shadows. The woodbine triptych was probably also intended for a drop-front desk, this time for the exterior of the drop-down writing surface rather than as a frieze across the top (as in fig. 4, discussed above).

The detailed woodbine nature study upon which this design is based (fig. 6) reveals that Steele transferred specific leaf formations and general contours from the study to the completed furniture design, but repositioned foliage to create compositional balance between the three individual panels. From the botanical study to the evolved three-paneled furniture design, she removed any shading or leaf veins and flattened the leaf forms, most notably in the central panel.

Whether working out in the field with her watercolor box or bringing plant specimens back to the studio, Steele knew that study of nature and reliable drawing were cardinal skills for a good designer, a doctrine espoused by both William Morris and John Ruskin. In a lecture delivered at the Trades Guild of Learning and the Birmingham Society of Artists, Morris noted:

The decorator’s art . . . does not excuse want of observation of nature, or laziness of drawing, as some people think. On the contrary, unless you know plenty about the form that you are conventionalizing, you will . . . find it impossible to give people a satisfactory impression of what is in your own mind about it, but you will also be so hampered by your own ignorance that you will not be able to make your conventionalized form ornamental.22

Ruskin, who was dismissive (or at least less enamored) of conventionalized forms in art, also insisted that any decorative art form must begin with direct imitation of nature, starting with the human form as a true test of ability. Anyone, he wrote, can create a conventionalized leaf design.23

This woodbine design, both in the nature study and in its tripartite translation into a desk front, has a compositional detail in common with Steele’s many botanical studies of azalea, dogwood, maple leaves, and more. The plant is presented as a single, diagonal branch, usually laid out from lower right to upper left. In an 1881 lecture at the Working Men’s College, William Morris described “the diagonal branch” as one of eight elementary construction tools in successful pattern design.24 Diagonal flower stems and boughs, sometimes creating an x-like

patterning or lattice-work, are common in his wallpaper designs. In Steele’s drawings, the diagonal orientation of the branches allows for the most surface coverage on the paper and, therefore, more compositional options for transferring the design to furniture. In one watercolor study of apple blossoms, Steele tilted the page and superimposed three vertical rectangles in pencil over the flowering branch in the manner that most appealingly filled the intended furniture panels with flowers and leaves.25

The cherry Drop-Front Desk with Iris Panels (figs. 7 and 8),26 one of the highlights of the Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild’s permanent collection, adapts Steele’s innovative three-paneled format to a low-relief carving rather than a painted design. Here, the five irises and their arcing leaves are compressed into a completely flat plane. The flat-carving technique employed for the irises amplifies the flatness of the design rather than creating a sense of dimensionality—as carving and relief usually do. It is as if the door were a large printing woodblock.

While Steele or her collaborator Edna Walker transferred their own pictorial designs to painted furniture, carvings at Byrdcliffe were often the handiwork of Giovanni Battista Troccoli, an Italian artist who lived and taught at the colony.27 Yet he was an advanced craftsman who excelled at intricate chiseling techniques rather than the simpler carving of the iris desk. Troccoli was prob-

ably the carver behind the dramatic linen presses with tulip-poplar and sassafras designs by Edna Walker located in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Walker’s known furniture designs are densely packed with botanical elements, like carpets of gracefully flattened leaves and flowers, and are considerably more abstract than Steele’s.28

Another three-part furniture design in the exhibition is an expansive charcoal and watercolor drawing depicting four crows (fig. 9), which, the inscription tells us, was intended for a low-relief carving. Open to full wingspan, the majestic crows are cropped in arbitrary, asymmetrical ways by the vertical divisions between the three panels. The drawing’s size tells us that Steele intended it as a to-scale template for the carvers to work from. Yet at nearly six feet wide, the crow design is much bigger than the linen presses, chests, or desks often appointed with inset paintings or carvings such as this. The penciled spacers of the crow drawing suggest it was for a piece with doors, perhaps a low sideboard similar to one located in the Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild’s conference room.

Typical of Byrdcliffe design, a continuous narrative allows the fragmented birds to coalesce in the invisible space behind the panel divisions, while pine branches29 occupy an additional plane of botanical décor. They are, again, arranged diagonally, providing a dynamic surface backdrop to the crows. The work is unusual because of the animal factor, with Byrdcliffe furniture design known largely for the botanical ornament favored by the Whiteheads. Antiquarian Robert Edwards mentions another bird design by Zulma Steele, “a huge black raven dropping into the upper panel of a desk like an ominous

shadow.” It is unclear which drawing he is referencing. The Guild has several drawings by Zulma Steele of birds for furniture design, yet none matches his description.30 But how did birds come to roost in the otherwise flora-centric, scenery-based ornamentation at Byrdcliffe? They are certainly the most common animal motif in William Morris’s stylized botanicals, while Ralph Whitehead seemed to like both birds and angels. Love, he wrote in the epigraph to Grass of the Desert, was half of each of those beings, and in an essay called “Modern Painters” (after Ruskin), he associates birds with the human soul.31 Heidi Nasstrom Evans tells us that Jane Whitehead designed the symbol on the cover of Grass of the Desert, 32 a highly stylized bird, mostly wing, carrying an arrow as more birds fly into the distance. The same stylized bird is intertwined with a fleur-de-lis on the title page. The Whiteheads followed this up in 1902 with another collaboration, a book of plates about the angel in art called Birds of God 33

And then, of course, there’s the fact that Jane Whitehead’s middle name was Byrd, and the colony hence named “Byrdcliffe”—her middle name combined with Mr. Whitehead’s, Radcliffe. This might have been a compelling reason to use a bird as part of any marketing identity for the crafts produced at the colony. Indeed, the stamp of the Byrdcliffe Pottery, which operated from 1903 to 1922, consists of stylized bird or angel wings.34 But the arrows and bird fragments are esoteric and heavyhanded—and the most enduring Byrdcliffe logo became, instead, the lily.

The Whiteheads’ emotional attachment to the lily perhaps originated with the fleur-de-lis crest of the city of Florence, one of many stops on their year-long honey-

moon, and a symbol they used frequently in their home décor, book designs, and more.35 Zulma Steele’s iconic hand-colored woodblock design of a lily (fig. 10) shows a vertical stalk bifurcating into two lily blooms, one open, one closed. More rigid, stylized variants of the lily decorate Steele’s table legs, chests, chair splats, and a unique footstool in the collection of the Woodstock Artists Association & Museum. The single lily of Steele’s woodcut was modified and contained within an octagon for the company furniture stamp, found on many pieces produced at Byrdcliffe in 1904. The lily also embellished Whitehead’s calling card.36

From her innovative three-paneled ornamentation and application of English Arts and Crafts stylistic priorities to Byrdcliffe furniture, to the graphic adaptation of her lily into Byrdcliffe’s company identity, and finally to the lily’s continued resonance in merchandise and marketing at the Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild today, Zulma Steele can be credited with nothing short of creating the Byrdcliffe brand. Ralph Whitehead, however, lacked the agency and financial incentive to figure out precisely how to work that brand into the public consciousness, and with nary a fight was overshadowed by the Arts and Crafts furniture production and promotional savvy of Gustav Stickley and, to a lesser degree, Elbert Hubbard of Roycroft 37 But that is another story, one very much at the root of why Byrdcliffe produced fewer than sixty pieces of furniture before shutting down the woodshop for good—a short chapter in Byrdcliffe’s long history.

Without the explanatory letters, treatises, or journals so coveted by art historians, we need to rely on Steele’s visual expression to determine that she was studying, or at the very least paying close attention to, William Morris’s Arts and Crafts design principles. Ralph Whitehead’s library of over 5,000 volumes was available to Byrdcliffe residents and was well-stocked with books on design.38 A 1908 photograph (fig. 11) shows a Morris tapestry hanging in the library, its pre-Raphaelite female figure presiding over the volumes, reminding readers of the utopian colony’s debt to this luminary of the Arts and Crafts movement.39 It must have been in Whitehead’s library, in part, that Steele derived some of the methods and motivations she took into her studio practice. No documentation points to her having ever received formal training in furniture design;40 and she developed a style that was at once her own and redolent of influence.

The final work by Zulma Steele to be studied here, her Hanging Shelf with Poppy Design (figs. 12 and 13), also from 1904, is a beautiful assimilation of conventionalized botanical imagery, Art Nouveau, and the romance of medievalizing books printed at William Morris’s Kelmscott Press, editions of which populated Whitehead’s impressive library.41 Mirrored forms of poppy flowers create ornate arabesques at each end of the shelf, with curling diagonal stems, tendrils, and flame-like leaves that read in a distinctly typographic way. The plants completely fill the shelf’s vertical panels, edge to edge, enclosed like ornate capital initials in an early manuscript. One of Steele’s notebooks has a page of medieval lettering exper-

iments, including an elaborate “ZS” monogram.42 The yellow background of the poppy underscores associations with the gold leaf of illuminated manuscripts.

Morris created three typefaces for Kelmscott’s sumptuously designed books, with capital letters festooned in spiky leaves and vines,43 common enough in type design. Yet Steele’s visits to Whitehead’s library would have been incomplete without perusing Morris’s illustrious handmade editions. The quintessentially Art Nouveau whiplash form of the poppy (which Byrdcliffe furniture designer Dawson-Dawson Watson also employed), the fully conventionalized treatment of the plants, and their allusions to an ornate typeface make Steele’s hanging cabinet a paean to the interdisciplinary design languages of the Arts and Crafts movement.

Two paintings and a ceramic bowl with decorative botanical border designs in the current exhibition demonstrate that Steele’s interest in the visual tactics of furniture decoration lingered long after the Bottega stopped production. Steele’s designs align the furniture produced at Byrdcliffe more closely with the English Arts and Crafts as represented by Morris (and as channeled through Ralph Whitehead’s own Englishness) than with the austere, representation-free designs of nearby makers Roycroft and Stickley—the latter a high-performing business that has become

synonymous with American Arts and Crafts. Perhaps the American public was not ready for pictorial representation on furniture, with plants prominently growing across their desks and sideboards. Steele’s and Walker’s designs were undoubtedly quite radical. Steele was a thinker who learned from close study of nature and design, and explored new topics, media, and styles. A series of large paintings of the Ashokan Reservoir highlight her strengths as a landscape painter; travels to Haiti and the Bahamas resulted in sensitive human studies; the 1913 Armory Show and painting instruction in France brought her in touch with European modernism; and, after 1922, she turned to producing ceramics in what used to be the Byrdcliffe Pottery.44 In 1939, she became a founding member and first chairperson of the Woodstock Guild of Craftsmen,45 established to give creators in the decorative arts an exhibition forum. When, in 1975, the Whiteheads’ son bequeathed the Byrdcliffe Art Colony to the Guild of Craftsmen (founded by women, it should be noted), the Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild was formed, today an important site for artists’ residencies, exhibitions, classes, and more. Steele died three years after the merger, at the age of ninety-eight. Without having planned it this way, she had founded the organization that went on to protect her original Woodstock home, the artists’ colony in which she came into her own.

1 Robert Edwards, “Byrdcliffe Furniture: Imagination Versus Reality,” in Byrdcliffe: An American Arts and Crafts Colony (Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, 2004), 74. Edwards’s essay remains the most comprehensive examination of furniture production at Byrdcliffe. Any signed Byrdcliffe furniture has the date 1904. Edwards, 81.

2 See, for example, a Zulma Steele poplar chest (carving attributed to G. B. Troccoli) in the Milwaukee Art Museum, Layton Art Collection Inc. (L1993.5.1); and an identically styled chest with painted landscape panels likely by Dawson Dawson-Watson or Victor Anderson in the Two Red Roses Foundation, Palm Harbor, FL.

3 Edwards notes that Byrdcliffe linen presses have a direct prototype in M. H. Baillie Scott’s “clothes press,” published in International Studio in 1898. Edwards, 78.

4 Ibid., 83.

5 William Morris, “Some Hints on Pattern Designing,” Lecture, Working Men’s College, London, 1881 (London: Longmans & Co., 1899), 4. Emphasis mine.

6 Ralph Radcliffe Whitehead, “Work,” in Grass of the Desert (London: Chiswick Press, 1892), 171.

7 See William Morris’s lectures “The Lesser Arts” and “Art for the People” for impassioned arguments about the relationship between happiness in labor (artistic and otherwise) and positive social change. William Morris, Some Hopes and Fears for Art (New York: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1901), 1–37 and 38–70.

8 Zulma Steele and Edna Walker have variously been called companions, roommates, fellow Pratt students, and friends. They lived together at Byrdcliffe for at least seventeen years and shared a studio in New York City during the winter. Various accounts exist but Walker is said to have gone to Scotland sometime around 1920 and was never heard from again; Woodstock writer Tad Wise proposes otherwise. In 1926, at the age of 45, Steele married Neilson Parker, her

first marriage; Parker died two years later and Steele never remarried. While finding verifiable evidence of a romantic relationship between Zulma Steele and Edna Walker is highly unlikely given the climate of secrecy around homosexuality in the early twentieth century, it is also unlikely that two women would live together for as long as Steele and Walker did without some kind of conjugal bond in place. Edna Walker is not mentioned in the one biographical document we have written by Steele (Archives of the Woodstock Artists Association & Museum). Tad Wise was recently the first writer to directly address the question of Steele and Walker’s probable relationship, with some creative conjecture. See Tad Wise, “Gender Blending in Early Woodstock and Our First Female Genius,” Woodstock Times (August 26 and Sept. 5, 2018), https://hudsonvalleyone. com/2018/08/26/gender-blending-in-early-woodstockour-first-female-genius/. Accessed May 27, 2020.

9 Alf Evers, Woodstock: History of An American Town (Woodstock: Overlook Press, 1987), 427–428.

10 Tom Wolf, “Art at Byrdcliffe,” in Byrdcliffe: An American Arts and Crafts Colony, 97–98. Dr. Wolf’s many years of research on Byrdcliffe have produced an encyclopedic resource for scholars. Murphy was the first painter hired by Whitehead to teach at Byrdcliffe, where he spent the summers of 1903–1905. He returned to his home state of Massachusetts and established the famed Carig-Rohane frame shop in Boston with Charles Prendergast, brother of the better-known painter Maurice Prendergast.

11 From a one-page autobiographical document in the archives of the Woodstock Artists Association & Museum.

12 Edwards, 77.

13 Thomas A. Guiler, “The Bottega,” UpstateHistorical accessed May 25, 2020, http://www.upstatehistorical.org/items/ show/6. Guiler’s website includes an interactive tour of the Byrdcliffe Art Colony and is an important scholarly resource.

14 Edwards, 77.

15 Evers, 424.

16 Guiler, “The Bottega.” Jane Whitehead is quoted by Ben Webster: “Oh, that’s a little too dark a green. I’m afraid that you’re going to have to sand-paper that down.”

17 Los Angeles County Museum of Art (AC1993.176.15.1), Drop-Front Desk, c. 1904. Oak, paint, and brass hardware, 51¾ x 44½ x 16¾ in. Byrdcliffe metalworker Edward Thatcher created the brass strap hinges.

18 Morris, “Some Hints on Pattern Designing,” 35.

19 A substantial portion of WBG’s permanent collection can be viewed at: https://collections.hvvacc.org/digital/collection/wbg1.

20 Morris, “Some Hints on Pattern Designing,” 6.

21 A chest with two painted panels attributed to George William Eggers also uses this device of a continuous landscape. Collection of the Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild (WBG 2015.001.005).

22 William Morris, “Making the Best of It,” in Some Hopes and Fears for Art, 151.

23 Drawing from nature is elemental to Ruskin’s ideas on art. His commentary on the decorative use of natural forms— in which nature by necessity dictates design—can be seen, for example, in John Ruskin, The Seven Lamps of Architecture (London: George Allen, 1903), 139. Elsewhere, in a lecture transcript, he wittily describes the ways in which conventionalized forms test the skill of a designer: “Whenever you want to know whether you have got any real power of composition or adaption in ornament, don’t be content with sticking leaves together by the ends—anybody can do that—but try to conventionalise a butcher’s or a greengrocer’s with Saturday night customers buying cabbage and beef. That will tell you if you can design or not.” John Ruskin, “John Ruskin on Decorative Art,” The Decorator and Furnisher 15, 1 (Oct. 1889), 15.

24 Morris, “Some Hints on Pattern Designing,” 16–17.

25 WBG 2003.004.052, Untitled (Apple blossoms or pink dogwood). Watercolor, ink and pencil, 19½ x 25¾ inches.

26 A similar iris design, this time in one panel, can be found in a hanging wall cabinet, approximately 40 inches wide, by Zulma Steele housed at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (90-40).

27 Nancy E. Green, “Cast of Characters,” in Byrdcliffe: An American Arts and Crafts Colony, 243.

28 Designs by Edna Walker include Metropolitan Museum of Art (1991.311.1), Linen Press with Sassafrass Design and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (2003.61), Linen Press with Tulip-Poplar Leaves, 1904.

29 WBG owns three preparatory graphite drawings of a possibly related pine triptych, approximately 11 x 18 inches each.

WBG 2003.004.038, 2003.004.042, and 2003.004.043

30 WBG 2003.004.040 (Crane), WBG 2003.004.041 (Four

Studies of a Bird) and WBG 2003.004.032 (Bird with Spread Wings). None of these have the “dramatic, foreboding” qualities referenced by Edwards, 77.

31 Whitehead, Grass of the Desert, epigraph, 115, 117.

32 Heidi Nasstrom Evans, “Jane Byrd McCall Whitehead’s (1861-1955) Idealized Visions About Simple Living and Arts and Crafts,” brochure essay published with exhibition of the same name, Georgia Museum of Art October 9–December 5, 2004. Reprinted at http://www.tfaoi.com/ aa/5aa/5aa36.htm.

33 Jane Whitehead and Ralph Whitehead, Birds of God: Angels and Sundry Imaginative Figures from the Pictures of the Masters of the Renaissance (New York, R.H. Russell, 1902).

34 See Ellen Paul Denker, “Purely for Pleasure: Ceramics at Byrdcliffe,” in Byrdcliffe: An American Arts and Crafts Colony, 108–119.

35 Evans, n.p.

36 The Winterthur Library: Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Collection 209. See http:// www.upstatehistorical.org/files/show/23.

37 For a description of furniture marketing, or its lack, at Byrdcliffe, see Edwards 74–75. For an examination of the three lesser-known arts and crafts colonies in the age of Stickley—Byrdcliffe, Rose Valley, and Roycroft—see Thomas A. Guiler, “The Handcrafted Utopia: Arts and Crafts Communities in America’s Progressive Era” (Ph.D. diss., Syracuse University, 2016).

38 Thomas A. Guiler, “Winterthur Primer: The Byrdcliffe Library,” InCollect, https://www.incollect.com/articles/winterthur-primer-the-byrdcliffe-library. Accessed May 26, 2020.

39 Whitehead purchased the tapestry in the 1890s. Nancy Green, “The Reality of Beauty,” in Byrdcliffe: An American Arts and Crafts Colony, 47.

40 Edwards, 83.

41 Guiler, “Byrdcliffe Primer.”

42 Loose sheet with ink and graphite lettering in notebook, 6¾ x 8¼ inches, signed Zulma R. Steele on cover. Collection of Janet Marsh Hunt. Thanks to the lender for allowing us to bring these notebooks to light, and to Tom Wolf for sharing his research into the collection.

43 For information on the most famous Kelmscott publication, the works of Chaucer with woodblock illustrations by famed painter Edward Burne-Jones, see https://www.bl.uk/ collection-items/the-kelmscott-chaucer. For the full alphabets of Morris’s typefaces, see this excellent resource by a computer science professor and self-professed typography nerd: http://luc.devroye.org/fonts-24795.html.

44 Denker, 108.

45 Michael Perkins, with a foreword by Alf Evers, The Woodstock Guild and its Byrdcliffe Art Colony: A Brief Guide (Woodstock: The Woodstock Guild, 1991), 45.

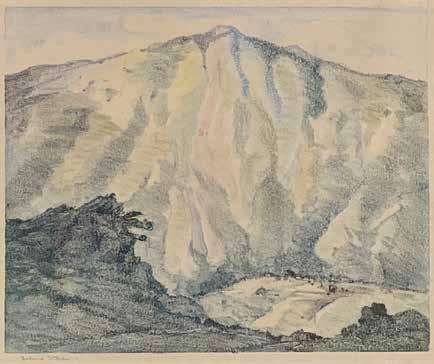

Zulma Steele’s aspiration as a landscape painter reached its peak with the creation in 1914 and 1915 of a series of paintings of Ulster County’s Ashokan Reservoir and the surrounding mountainsides. The complete size and scope of this luminous series is not known.1

Six paintings were acquired from Steele’s estate after her death in 1979 by Jean and Jim Young of West Hurley, New York.2 One of these, Headwaters of the Ashokan Reservoir (fig.1), is now in a different private collection in Woodstock. The group captures the beauty of the reservoir and its environs as the project neared completion and the reservoir was still being filled with water. The paintings range from panoramic views of the reservoir and the mountain ranges in the distance, to more intimate glimpses of the water and the nearer terrain. Four of the works feature the reservoir’s east basin, and two picture the west basin. Steele inscribed the titles on the back of several paintings in black ink, along with her name.

The Ashokan Reservoir is the oldest New York City-owned reservoir in the Catskill Mountains (fig. 2).3 It is situated fourteen miles west of the Hudson River at Kingston and is approximately four miles walking distance from the village of Woodstock to its eastern edge in West Hurley. By the early years of the twentieth century, the Croton Reservoir

in Westchester County was deemed insufficient to supply the water needs of New York City’s growing population through the coming decades. In 1905, New York’s Board of Water Supply was empowered to develop and implement a plan to expand the city’s water system. They focused on the Esopus Creek in the Catskill Mountains of Ulster County, which, as early as 1886, had been proposed as a potential water source. Almost twenty years later, the board formally proposed the Ashokan Reservoir and the accompanying Catskill Aqueduct to slake the city’s burgeoning thirst. The Catskill Aqueduct would bring the drinking water from the reservoir more than ninety miles to the Kensico Reservoir, just north of White Plains. There it would mix with water from the Delaware Aqueduct and flow a few more miles into the Hillview Reservoir in Yonkers, from which it would be distributed to the city’s five boroughs.

The Board of Water Supply’s plan for the Ashokan Reservoir placed its center near Brown’s Station and called for the flooding of thousands of acres of land used for farming, logging, and quarrying. More than 2000 residents would have to be relocated and some 1,200 acres of homes, barns, mills, stores, churches, graveyards, orchards, farms, pastures, and quarries cleared. The land was acquired under eminent domain over the strenuous objection of local opponents, including those who had initially resisted moving from the area or demanded additional financial compensation, and those who feared that

this was just the start of New York’s plan to suck Ulster County dry. Many were also fearful that the dam would loom as a perpetual menace to people and towns downstream. Finally, some opponents believed the reservoir would not hold enough water even for the city’s immediate needs.4 In the face of the opposition, an equitable method for establishing the financial value of the land was established, even as many residents ordered to move continued to fight the issue vigorously in the courts.5

Time has borne out the value and the success of the controversial reservoir, and local fears proved unfounded. The project was constructed jointly between 1907 and 1915 by MacArthur Brothers Company and Winston and Company, enlisting the labor of thousands of workers. After the Esopus Creek, a major tributary of the Hudson River, was dammed, construction of the reservoir itself commenced. Today, it consists of a chain of masonry and earth dams and dikes with a combined length of five and a half miles. Rising to a height of two hundred feet, the Ashokan Reservoir is 196 feet thick at its base, holds 122.9 million gallons of water at full capacity, and continues to supply New York City with a staggering 40 percent of its drinking water during drought periods.

The Ashokan Reservoir was broken into upper (west) and lower (east) basins, and the reservoir extends from the headwaters of the creek, close to Boiceville in the upper basin, down to the lower basin in West Hurley. A causeway runs between the basins, providing a connection for people traveling between the northern and southern sides of the reservoir. The upper basin borders the relocated villages of Boiceville, Olive, Olivebridge, Shokan, and West Shokan, and the lower basin borders the relocated villages of Ashokan, Glenford, West Hurley, and the original (non-relocated) village of Stony Hollow.

In March 1912, workers were hired to remove every tree, bush, orchard, fence, grave, house, and farm from what would become the reservoir floor. This process of demolition ended when construction of the dam was coming to completion in September 1913. By late spring of that year, the landscape was a scene of desolation and ruin. As journalist Ella Lockwood Loomis reported in the Kingston Daily Freeman, it looked as if “a conquering army had recently marched through the territory,” and the writer E. G. Nimsgern accurately forecasted that, when

fully cleared, the tract would be “more barren of vegetation than the barren Sahara.”6

Following the end of construction in September 1913, the Board of Water Supply stopped the flow of the Esopus Creek and allowed the water to accumulate. Initially, the Esopus flowed at a rate of 22 cubic feet per second. In The Last of the Handmade Dams: The Story of the Ashokan Reservoir, Bob Steuding reports that the summer had been dry, and the waters of the area seemed to be stalled while “others said the bottom of the reservoir was porous, and it would take some sort of expensive compound to caulk the leaks—it seemed like the reservoir would never fill.” 7 But by the end of 1913, a succession of heavy storms filled the west basin to half its capacity. In mid-December the water in the basin had reached a level of approximately 100 feet and impounded over sixty million gallons of water.

The flooding of the Ashokan Reservoir was completed in early December 1914. Six months later, the Board of Water Supply announced that, after more than seven years of work, water from the Catskill system was fully available for New York City. The Poughkeepsie Eagle News reported that it was now “possible to use the water from the Ashokan Reservoir in any part of the five boroughs of Greater New York. It will only be necessary to connect the supply from the aqueduct to the pipes leading to whatever section will need it most.”8

Once the vast tract that had been denuded as if by an invading army was fully submerged, the Ashokan Reservoir area was instantly recognized as one of the most beautiful locales in New York State. It soon became a favorite attraction and source of enchantment and relaxation for tourists and area residents alike.9

On its completion, The New York Times called Ashokan the “greatest reservoir in the world” and deemed the complexity of its construction comparable to the building of the Egyptian pyramids.10 Picture postcards celebrated the reservoir’s seamless combination of artificial and natural beauty.11 For many, the reservoir looked like a natural mountain lake surrounded by wilderness. T.

Morris Longstreth wrote admiringly of the Ashokan Reservoir in his travel book The Catskills, published in 1918. For him, the reservoir was— a revelation of completed beauty. The lake was so beautiful, fitted so well into border-land of mountain and