13 minute read

Cover Story

Uncovering Worcester’s hidden Black history

Robin Shropshire, a local voice actor and board member of the Whitlock Theatre Company, will be hosting a video series put on by the Worcester Black History Project.

Advertisement

VEER MUDAMBI

The Worcester Black History Project, which documents and celebrates the city’s rich African-American narratives, is relatively new, having held its first exhibit at City Hall in 2018. But that fact itself sparks the question, why has the past of the Black community here not been appropriately spotlighted until so recently? Especially in a city with history to spare — after all Worcester is older than the nation, having been founded in 1722.

Robin Shropshire, whose father was one of the first Black police officers in Worcester, has an insight. “Sometimes it takes an outsider to come into the community and see how rich of a history exists.” In this case, she’s referring to Debbie Hall, a Worcester resident who upon moving here from St. Louis began to inquire about the history of the local Black community. In late 2017, Hall organized the first meeting of the WBHP.

For members of the Worcester Black community, said Shropshire, it’s not history, it’s just their life. “For the longest time, I didn’t think about my grandparents and parents as history.” When a minority has been suppressed to such a degree, ordinary events can be milestones, which in turn become history. But this history is only just starting to be acknowledged and given its proper place by institutions such as historical and art museums.

For Shropshire, history meant “towering figures, governors and presidents, people with books written about them — but the dominant culture is the one who decides who these figures are.” With the formation of the WBHP and understanding that history is created in everyday lives and families, “people have begun going through their attics, sitting with their grandparents, listening to their stories and sharing them.”

WBHP’s latest initiative is called Worcester Black History Moments, launching in time for the first MLK Day and Black History Month since the summer BLM protests.

Initially, the WBHP and the Worcester Historical Museum set up an exhibit with more planned for later but with the onset of COVID, the museum was closed to the public. Out of a joint need to convey museum exhibits digitally as well as portray information in a more creative medium, the WBHP steering committee conceptualized the history videos — released monthly, each five to seven minutes long to spotlight local Black historical figures and events. The project will be a collaboration with the WHM and the American Antiquarian Society, headquartered in Worcester.

The idea for the BHM video series came about in late 2020, during a meeting of the Black History Project board to create “history tidbits” in easily digestible form. Their production is a team effort with the WHM in charge of researching, writing and editing the scripts. All the institutions involved encourage Worcester residents to share their stories and history to create a joint narrative, in effect a “grassroots historical research project in which everyone can participate,” according to David Connor, WHM Outreach Coordinator. Videos will be hosted by Shropshire, who has experience in voice acting work, but each episode will be narrated or led by others.

The first video will focus on William Brown, the first African American to be inducted into

COLLECTION OF WORCESTER HISTORICAL MUSEUM

the Worcester County Mechanic’s Association. The idea of such organizations came from Europe during the Industrial Revolution and the Mechanics Association was formed in the Blackstone River Valley as an educational organization for the burgeoning manufacturing industry in Worcester. Part of the decision to begin with Brown was because his descendants, the Goldsberrys, who still live in Worcester, are being honored at the breakfast and it seemed fitting to start off the series with their ancestor.

Additionally, the Mechanics Association has begun the process of having Brown’s portrait placed in Mechanics Hall along with that of abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who spoke there. The decision to add the portraits was announced in September 2020. The portraits will be commissioned and the process is expected to take up to two years.

Kathleen Gagne, executive director at Mechanics Hall, indicated that Mechanics Associations have always been involved in major social issues such as abolition and women’s suffrage, so the Worcester association intends to do its part in bringing neglected aspects of history to light. Gagne said the new portraits will be a “catalyst” for the association to bring the greater community into a wider discussion about the position of

COVER STORY CONTINUED FROM PAGE 11

people of color in the 19th century, as well as modern day.

As far as the portraits are concerned, they are examining fundamental questions such as style and will begin the process of finding artists and fundraising in February. The pieces will be done in the 19th-century portrait style, in keeping with the other portraits in the Great Hall. The decision to do so is more than just a matter of aesthetic, it’s also respect, said Gagne. “Best for compatibility and to honor these people, the way they should be honored,” she said. “If we were to deviate from that, it would separate them again and this time forever.”

William Brown’s place in Worcester history is a respected one. Kimberly Toney, head of readers’ services at the Antiquarian Society and member of WBHP Steering Committee, said “there is a long legacy of Brown’s influence in Worcester.” Born in Boston, he came to Worcester as a young teenager, shortly thereafter establishing himself in the upholstery business. His clientele included the city’s wealthy white residents, and their houses had many examples of his upholstered furniture and draperies. The success of his business helped him garner a great deal of respect within the white community while at the same time, he remained a force for Black activism, being able to “straddle both spheres,” said Toney.

The Brown family papers, donated by a descendant in 1974, followed by more material in 2019, are a collection of letters, photographs and books detailing Brown family life in Worcester.

While they are only a small piece of a larger, hidden history of the Black community in Worcester, it could only be brought to light with the help of the family. “I can only imagine what other knowledge lives within (local) families,” said Toney, “insofar as people are willing to share it.”

A perfect example of grassroots historical research, the Brown family papers provide a

At Hope Cemetery, Benetta Kuffour searches for the graves of her ancestors. Her great-great grandmother, Bethany Veney, was born an enslaved woman in Virginia around 1812 and moved to Worcester just before the Civil War. Many headstones in the large family plot are missing now.

unique perspective. Worcester was a city of abolitionists and Brown acted as a “quiet organizer” operating behind the scenes, said Toney, so his name may not be a staple in history books but he fought just as hard as other, more well-known figures, some of whom he was closely associated with.

When Brown’s wife, Martha, died, Frederick Douglass wrote in a letter dated July 11,1889, that he remembered her fondly from “the early times.” The Brown family papers also contain correspondences to Brown and his family from friends serving in the 54th regiment, the all-Black regiment from Massachusetts in the Civil War, for which Brown was a recruiter.

Benetta Kuffour, the descendant of another famous name in Worcester Black History, is also on a mission to share her ancestor’s story — but she finds that it’s not always easy. In fact, it wasn’t until her late 20s that she learned about her great-great grandmother, Bethany Veney, who was born an enslaved woman in Virginia around 1812 and moved to Worcester just before the Civil War. “My family didn’t share our history very well,” Kuffour observed wryly.

In the 1850s, anti-slavery activist G. J. Adams purchased Veney and her son Joe and brought them back to his home in Providence. When the Adamses moved to Worcester, Veney brought gruel to sick Union soldiers, worked as a laundress, and went door-to-door selling bluing solutions for clothes. When the Adamses left Worcester, Veney chose to stay on.

She quickly became a force in the local Black community and is the subject of the second Black History Moments video for February. Veney’s video will be a combination of WHM, AAS and Kuffour’s records.

Unfortunately, in the intervening 100 plus years since Veney died, the city has lost track of something as basic as her grave site. Toney is not surprised. “It’s hard to find a lot of details of Black life in Worcester because of the marginalization of people of color, but there is stuff all over the place in our collection that sheds light on the life of people of color in Worcester.” Indeed, it takes some digging because of how Black people may

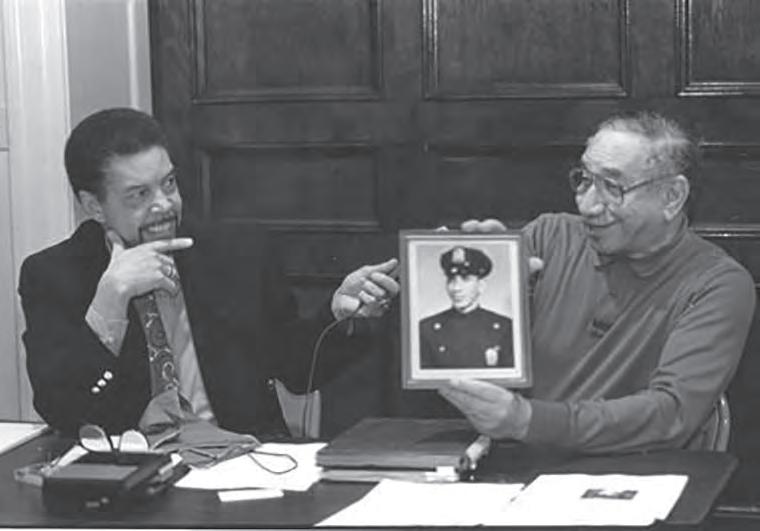

One of Worcester’s first Black police officers, Louis Shropshire, is seen in a photograph from the the ‘Looking Back, Facing Forward 1990s’ exhibit.

WORCESTER HISTORICAL MUSEUM

or may not have been represented due to the times.

As a Black woman in the 1860s, Veney established a successful business selling bluing solution (bleach) and was able to return to her home state of Virginia to purchase and free more than 16 family members, bringing them back to Worcester. She lived to 103, earning the moniker “Aunt Betty” in her adopted city. Kuffour points out that ”it is an embarrassment to the city to not have that headstone.”

In 2003, Gov. Mitt Romney named July 12 as Bethany Veney Day. During a family reunion that year to celebrate the declaration, Kuffour first noticed the missing headstone — a discovery that began her quest to find and restore her ancestor’s grave. Returning to the cemetery a few years later, she also found that the headstone of Aaron Jackson, Veney’s son-in-law, had been vandalized. While Jackson’s headstone has since been repaired, it’s now been moved from its original location and no longer marks his grave. “They just kind of move things around to an empty space,” Kuffour observed. For her, it’s indicative of how systemic racism, manifesting through a casual neglect of African Americans, continues on even after death. “Nothing’s changed,” she said.

Veney had originally purchased 16 plots for her family at the cemetery and her grave had a standing headstone. She was buried alongside the rest of the family, some of whom had plaques but those have since disappeared as well. Working from a list of family members from infants to adults who are buried there, Kuffour said she told her family that they should get a large headstone with all the missing names.

In the 100 plus years since Bethany Veney died, the city has lost track of something as basic as her grave site. Toney is not surprised, “it’s hard to find a lot of details of Black life in Worcester because of the marginalization of people of color, but there is stuff all over the place in our collection that sheds light on the life of people of color in Worcester.” Indeed, it takes some digging because of how Black people may or may not have been represented due to the times.

Veney, who could not read or write, dictated her narrative to an unnamed assistant. The 1889 autobiography, “Aunt Betty’s Story: The Narrative of Bethany Veney,” shows how she forged a path to her own freedom, lived by a strict honor code and was active in the Methodist church revivals that were sweeping through the country at that time. Veney, who received the key to the city, died in her home on Nov. 16, 1915. Her house at 21 Tufts Street — now 33 Winfield Street — still stands on the west side of Worcester in the historically Black neighborhood between Mason Street and Beaver Brook.

LUNCH Monday-Thursday, 11am-4pm $6.99 East Brookfield Burgers DINNER Monday & Tuesday, 4pm-Close $10.99 Meals (entree& salad) Wednesday, 4pm-Close Italian Night $10.99 Italian Specials with salad CasualWaterfrontDining onLakeLashaway 308EastMainStreet, EastBrookField 774-449-8333 308lakeside.com FreeValetParkingFriday & SaturdayNights

GETYOURSMILEBACK!DON’TSUFFER FROMBROKEN-DOWNORMISSINGTEETH!

DENTAL

IMPLANT

SPECIAL*

INCLUDES CT SCAN,TITANIUMIMPLANT, CUSTOMABUTMENTAND PORCELAINCROWN $2,99999 FREE

*ExclusionsApply DENTAL

IMPLANT CONSULT ($200 VALUE)

Dr.SalmanKhananiDr.SalmanKhanani 1084MainSt.,Holden |khananidental.com | @khananidental *Some exclusionsmayapply:patientmustbe acandidatefordentalimplantsandsomepatientsmay requirecomprehensivetreatmentplanstomeet theirindividualneeds.Specialdoesnotincludethefeefor extractions,bonegrafts,sinusaugmentationortheneedfor asurgicalguide Call508-829-4575tobookyourappointmenttoday!

Implant, Cosmeticand FamilyDentistry

Worcester 31 CarolineStreet Plantation Street area ... Brandnew One-bedroom apartment...includeswasher/dryer, storage, off-street parking, heat andh/w... No smoking, no pets.

Worcester Center Hill Apts 503-505 Mill St....TheTatnuck area’s newest apartment homes. large 1&2BR, W/Din each apt, storage, elevator, heat &hot waterincluded. Nicewalkingarea. No pets.

A Worcester Black Lives Matter gathering in 2020.

WORCESTER BLACK HISTORY PROJECT ARCHIVE

COVER STORY CONTINUED FROM PAGE 13

WHM Executive Director Bill Wallace believes in educational programs and outreach on behalf of WBHM, along with the importance of historical material provided by the community. “He’s been so eager to not only hear these stories but to provide a repository,” said Shropshire. Some of the topics that the museum will be putting front and center during Black History Month are Black policemen, panel discussions about the challenges that faced the community and the display of unseen photographs of the Black community from the collection of William Bullard, courtesy of the Worcester Art Museum.

Back in February last year, the city of Worcester in conjunction with WBHP and the Worcester Police Department held an event honoring the first three Black police officers, one of whom was Shropshire’s father. That got her thinking about “what is history and who gets to write it? Even if you were a cobbler, if you were the first cobbler or the best cobbler, that is still history. We need to rejoice in these people where we find them, not to say they didn’t meet the bar because it’s a white bar.”

One of the goals of the WBHP is to uncover hidden stories which will have the result of showing how “every part of our story is an important part of our history.” Shropshire, who is on the board of the Whitlock Theater Company, is optimistic that the production of a play called “The Niceties” would strengthen this message. Whitlock in collaboration with WBHP would use this to kick off the next theater season, but she is not sure when that will be due to COVID. The play discusses how academia is a very different place for people of color and how history is told by the dominant society. She hopes to have a discussion panel including the WBHP and WHM following the production.

Kuffour also weighs in on how history is written by the majority culture. She underlines that Veney was unusual in that she was a woman who bought a home for her family, supported them with house cleaning, gardening and cooking, and was active in the church and the community. “As with other African Americans who have lived here and contributed, she is not acknowledged.” While Kuffour is not a writer, she has been putting her thoughts down and wants to make a scrapbook so her discoveries about her ancestor are not lost again. She wants to give it to someone who will continue the research and “follow through.”

With the positive changes in how Black history is documented and treated by Worcester institutions, community members like Kuffour can be assured that their findings will not only be preserved but expanded.

ARTIST SPOTLIGHT

Generations

Raised on a small former dairy farm, Natalie MacKnight is drawn to images of farmland, open meadow, trees, and rocks. She now resides in Boston, and more of her work can be seen at her website, http://www.macknight-studio.com. This image is “Generations,” gouache on watercolor paper, 18” x 12”.