12 minute read

Featured

Vanilla Box Productions presents ‘Love Stories’ including ‘Other Letters,’ two men’s story

RICHARD DUCKETT

Advertisement

In the late playwright A.R. Gurney’s popular 1988 “Love Letters,” a male actor and female actor read to the audience letters and notes between Andrew and Melissa from early childhood through their respective marriages, children, and, in Melissa’s case, divorces.

There is a good deal of humor in what is read and the authors of these letters do love each other, but for various reasons important opportunities get lost.

In “Other Letters,” a play by Bryan Renaud and Carin Silkaitic inspired by “Love Letters,” Charlie and Tommy begin passing notes when they are 8 years old. What follows are lives and a love similarly told in letters, notes and emails with some connections and lots of near-misses.

For the Vanilla Box Productions presentation of “Other Letters” that will be live online for four performances starting Feb. 19, the two characters are played by Kyle Collins and Norman Dubois of Worcester, who are a couple in real life.

“I think you have a mix of both powerful scenes that deal with loss but it is really funny,” Collins said of “Other Letters.”

Like “Love Letters,” when Charlie and Tommy are “ready to jump into their relationship, something always comes up,” said Dubois.

“Other Letters” debuted in Chicago 2016. Renaud and Silkaitic have also written a version for two women.

The letters and notes between Charlie and Tommy begin in the 1970s. One of the characters gets put through conversion therapy by his freaked out parents.

However, “It’s not too focused on the fact they’re gay, it’s more focused on their relationship and they happen to be gay,” Collins said.

“It’s very relatable. I didn’t grow up in the ‘70s, but growing up in the ‘90s a lot of what they talk about is very relatable.”

“Other Letters” is part of a double-header of plays being put on by Vanilla Box Productions with Valentine’s Day in mind under the overall title of “Love Stories.”

The other play and the first part of “Love Stories” is “Blind Date Trilogy,” a very recent work by Tanis Galik made up of three scenes. In the first, Stanley and Alice are each getting ready for their blind date. The second depicts the aftermath, and in the third scene there is another couple and a surprise. The cast is Christopher Pinkerton, Dalita Getzoyan, Paul Spanagel and Heidi White.

“Love Stories” will be presented live online at 7:30 p.m. Feb. 19, 20, 26 and 27.

Vanilla Box Productions has staged many large musicals at live, in-person productions at the former Holy Name Central Catholic Junior/Senior High School in Worcester, now St. Paul Diocesan Junior-Senior High School.

With the pandemic, the theater group co-founded by Christine C. Seger and Joel D. Seger has been putting out a number of live online productions over the past few months. The actors perform from their homes and Joel Seger links it all together.

“Vanilla Box Productions has become known for producing family-friendly musicals. Producing virtual plays gives us a chance to explore beyond what we were doing and expand our offerings,” said Joel Seger, who is directing “Love Stories.”

“One way we can push the boundaries is to tell stories that are not always heard and show characters that are not always seen. We are trying to be more aware and more inclusive when picking shows. Since Act One (of “Love Stories) showcases a more traditional romantic narrative, we chose a show to complement that in Act Two which shows the complicated relationship of two men that meet when they are in grade school. We couldn’t be more excited to share these shows that we believe haven’t been seen in this area before,” he said.

Joel Seger approached Collins and Dubois about “Other Letters.” Although the two actors had never worked at Vanilla Box Productions before, they knew the Segers, Dubois said.

“It’s great. We’ve never been like a couple onstage before. It’s a new experience for us. It’s a good experience for us,” Dubois said.

“It’s nice,” Collins said. Previously “We’ve played Frankenstein and Igor (in ‘Young Frankenstein’).”

Collins and Dubois met doing theater while students at Framingham State University.

“We were friends for a while. It developed into more,” Collins said.

They have both been active on the area theater scene, each drawing good reviews. They have also appeared in shows together, including with the Regatta Players (“Young Frankenstein,” “Dirty Rotten Scoundrels”) and Worcester County Light Opera Company. But that isn’t always the case and they have been up for the same role in a show.

A male couple auditioning for a role can be have a different experience than a male and female couple auditioning, Collins noted. “I feel a couple that are a man and a woman, they’re not going for the same roles. With us, one of will get the role and the other one won’t — but we can be there for each other.”

They were both in WCLOC’s “The Drowsy Chaperone” in December 2019. “Which feels like it’s not actually a year ago,” Collins said with a nod to all that has happened in the world since.

Away from theater they both have day jobs. Collins works at the laboratories of Worcester State University doing prep for lab courses. Dubois is employed at the St. Vincent call center.

Collins is originally from Framingham and Dubois from Milford, but they settled in Worcester believing it has a tremendous upside for the arts. Both emphatically said they would like to be professional actors here. “Yes.” “Yes.”

“I think that Worcester is on a horizon to have professional theater start popping up. I would really like to do that. We’ve been trying to get our feet in the door,” Collins said.

Further afield, they were both in an online North Shore Players production of “The Importance of Being Earnest” Nov. 7, with Collins as Algernon and Dubois playing Jack.

Still, with the pandemic, “We haven’t seen as many auditions and shows going up, so it’s really nice to be asked by Joel to have this opportunity,” Dubois said.

Collins and Dubois will be reading the letters from their kitchen with a camera set up.

“Kyle and Norman are wonderful,” Seger said. “They are bringing a lot of life to these notes, cards and letters that the characters send to each other. I found myself drawn in to the story and even emotional during rehearsal. The concept of the show is simple, which means the audience can really focus on the characters and the story.”

“It’s not just two guys reading letters, it’s our own (character’s) story,” said Collins.

“It’s interesting playing these characters. Interesting to see the depths of the relationships and how that comes out when we’re performing,” Collins said.

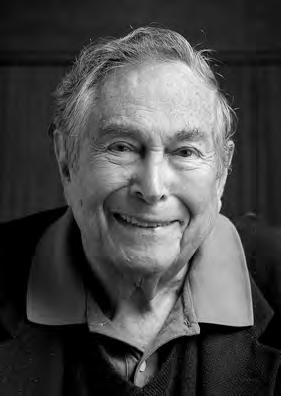

Norman Dubois and Kyle Collins, a couple in real life, star in “Other Letters,” part of Vanilla Box Production’s upcoming presentation of “Love Stories.”

LAUREN PIANDES

The broken billy club: Worcester lawyer Burton Chandler recalls groundbreaking civil rights case in city

VEER MUDAMBI

Burton Chandler didn’t set out to become Worcester’s go-to civil liberties lawyer. But as a young, aspiring corporate lawyer, who had been practicing for about nine years, he challenged the city in the name of social justice. After that, he says now, “anyone who had any kind of civil liberties case against the city of Worcester came to me.”

In the first Black History Month since the murder of George Floyd, after a year when we witnessed nationwide Black Lives Matter protests, it is worth noting Worcester’s early civil rights case. The deaths of George Floyd and many other Black men at the hands of law enforcement have forced the country to acknowledge how skin color drastically impacts lived experiences, especially during interactions with the police.

At a time when there were no reported cases of police brutality in the Commonwealth, Chandler represented two young African American men and their white brother-in-law, filing suit against seven Worcester policemen for excessive violence and undue force. The Hazard et al. v Rida et al. trial ended in spring 1971, and a decision favoring his clients was handed down in late 1972. “(It) certainly had the most publicity and press, being the first case of its kind in the history of Worcester, Mass,” Chandler recalled.

The case landed in his lap in October 1968 when Chandler’s wife, Harriette, now a state senator for the 1st Worcester District, returned from a meeting. “The place and purpose for [the meeting] has been lost in the dustbin of history,” said Chandler. “She met a couple of black kids who had been beaten up by cops and couldn’t get a lawyer to represent them, so she told them, ‘don’t worry I’ll give you my husband.’”

Initially, Chandler said he wasn’t too worried about being volunteered, as he planned to ask a colleague who was a trial attorney to take the case. When the other lawyer refused in order to avoid going up against the Worcester Police Department, Chandler was left with no choice but to take it himself. The senior partners in his law firm cleared the way for him to do so, even though he explained that his clients couldn’t pay his fees. “I couldn’t believe it,” he said, the surprise still evident years later. “At the time, law firms were not doing pro-bono work for minority groups,” unlike today where it is viewed as good publicity.

The lead client was Aaron Hazard, a 22-year-old veteran who was honorably discharged and working as a letter carrier for the USPS. His brother was five years younger and their brother-inlaw was 20 years old. They were accompanied by Hazard’s friend, Kenneth Troy, who left before he could be arrested and was later referred to by Chandler as the “chief witness.”

Hazard, his brother-in-law and Troy were waiting to pick up Hazard’s younger brother from a friend’s house when police pulled up and asked what they were doing in that neighborhood, Troy recounted. “We explained but the cop said we were giving him bull(expletive), and he also told us he had a short fuse and the next thing we knew, billy clubs were swinging.”

They were accused of drunkenness and disturbing the peace with disorderly conduct yet were asked to drive home on their own — unusual since visibly drunk individuals are usually not allowed to drive home. When they refused, they were beaten at the scene, arrested and struck repeatedly at the police station in full view of other officers, who did not prevent the violence.

Police officers claimed it was a peaceful arrest, but the plaintiffs had to seek medical help at a hospital for severe injuries, right after they were bailed out by Hazard’s wife and their local reverend. Hazard recalls how at the hospital, the nurse took one look at their injuries and assumed they had been in a car accident. That same nurse would later testify to the state of their injuries. The police steadfastly denied beating the young men and would “claim that in the 20 minutes or so after we left the station and got to the hospital, we either self inflicted injuries or something equally bizarre,” said Hazard.

All three young men lost their jobs while they recovered, and the hospital records and doctor and nurse testimonies were consistent with their statements. A broken billy club discarded at the scene also provided material evidence of the intensity of the attack during the arrest. The club was picked up by Troy, who went back to the scene to search for Hazard’s broken glasses. “[The officers] could not explain the broken billy club,” Chandler said.

The trial in the District Court of Worcester was a jury case, in which the three young men were found not guilty of the drunkenness charges but guilty of disturbing the peace and fined $10 each. The result was unsatisfactory for both Chandler and his clients, who believed the officers had to be held accountable for their actions. “By this time, I had determined to go ahead with a complaint in the Federal District Court in Boston, alleging civil rights violations and undue force or, in the vernacular, ‘police brutality,’” Chandler said.

Despite his firm’s generosity, Chandler knew money was still a serious issue. He consulted with the Worcester NAACP, which provided the entire content of its bank account to cover the expenses of the plaintiffs.

Unlike the previous trial, the proceedings in the Federal Court were presided over by a judge instead of a full jury. On the day of the trial, Chandler arrived “to see the entire city law department sitting at the defendants’ table. “That got my adrenaline pumping.”

Chandler had asked for all witnesses to be sequestered so each would not hear the previous testimony. That, Hazard said, proved to be an artful move since the officers could not coordinate their stories. “One cop comes in, gives his account, then sits down and listens to the subsequent testimony — with all the conflicting information, it was literally a case of the cops holding their heads at the gaps in their stories.”

Chandler had heard that some city official had suggested Chandler might be too afraid to make an appearance because of his inexperience. But Troy said that they always had faith in Chandler. “He was asking the right questions and looking in the right places.”

After 19 months, the judge did ruled in favor of Chandler’s clients. “We were getting nervous,” Hazard admitted.

But the story did not end there.

The city announced it wouldn’t pay the damages awarded to the plaintiffs, asserting that the individual policemen were responsible for the monetary charges. Chandler knew getting the money from the policemen would not be easy. “So I did a search and found that the three policemen ordered to pay owned their own houses,” he said. “So I attached their houses.”

His unprecedented step of placing a lien on their houses outraged the WPD.

The matter was brought before the City Council, who eventually agreed to pay — with interest.

In retrospect, Chandler said it’s “hard to say if the police really learned anything.” But he said the case sent a clear message, and “the city was never terribly friendly with me after that.”

This was even more true for Hazard and his brother, who said they endured subsequent police harassment. “The big joke was everywhere I went, I had a police escort,” said Hazard. “Everywhere we went we were followed — to the point that none of us would go anywhere alone.”

As lead counsel on many prominent civil rights cases in the city, Chandler was dedicated to the preservation and defense of individuals’ rights and liberties but he never stopped practicing commercial law. The American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts honored Chandler in 2008, with its Lifetime Achievement Award.

His other cases included gender discrimination in the school system and military. After the police case, “word was out that I was a civil rights lawyer,” he said.

For the most memorable of his civil rights cases, Chandler was gratified to see the young men flourish in the following years. “After the case, both brothers went to Worcester State College on scholarships from the Black community, and went on to have very successful careers. One was vice president of an airline company.”

Fifty years before the BLM and Defund the Police movements, Chandler successfully prosecuted a police brutality case in federal court and the precedent that it set was key to holding law enforcement accountable.

“We used our case as a model, down the years whenever we met someone who had been victimized by the police, that you can really do something,” said Hazard.

Worcester lawyer Burton Chandler

RICK CINCLAIR