14 minute read

Cover Story

Beyond Shrewsbury Street

Revisiting Worcester’s Italian-American heritage

Advertisement

CRAIG S. SEMON “ L et me say a word about Shrewsbury Street. This was, and will forever be, the heart of the Italian community of Worcester. The very name is integral with the Italian Community. Anyone in Worcester who thinks of the Italians, instinctively thinks of Shrewsbury,” according to Rev. John J. Capuano (deceased), pastor of Our Lady of Mount Carmel-St. Ann Parish, in “A Brief History of the Italian Americans of Worcester, Massachusetts from 1860 to 1978.”

There are four absolutes for any true Italian who grew up in the Italian section of Worcester in the 20th century – a strong work ethic, a devotion to family, a belief in a good education, and, of course, a passion for food, fabulous, homemade food.

While those absolutes still hold true today, some Italian-Americans argue that the younger generation has lost sight of the significance of some of these inherited principals – but, not the food, no, never the food.

When you ask Mauro DePasquale and Carmelita Bello what does it mean to them to be an Italian-American growing up in Worcester, they both simply say “Everything,” before rattling off their personal family history for the next 10 minutes that truly captures the 20th-century Italian-American experience.

DePasquale and Bello, who are both 100 percent Italian (and very well known in the Italian community and beyond), have fond memories that go back when they were very young.

“I lived off Bell Hill. There were mostly Italians. And I thought everybody was Italian,” DePasquale said. “I can remember one of my grandfathers holding me when I was one year old and he had a tattoo of Christ tied to an anchor. I have a chain with that right now that I’ve worn since I became old enough to buy one. I remember visiting my grandparents and them taking me into the garden. One of my grandmothers made wine. She showed me the machine when I was just a little kid. And I thought this was so cool. These people didn’t need anything. They could make stuff. When I was hanging around my grandmother, she would come and visit and help my mom out when we were little kids. My mother had six kids. My grandmother would look at me and say, ‘What do you want to do?’ I said, “I don’t know?” “All right, let’s make some polenta” and she’d make polenta or she would bake a loaf of bread or pasta or pizza fretta and show me how to do it. She made all this stuff and I just became so infatuated with the fact that you didn’t need a grocery store other than to get the real essential essentials. And I was so proud of them. If I had an opportunity when I visited my father’s side, I go visit my grandfather. He’d teach me Italian card games like Scopa (broom in Italian). But, he wouldn’t just play cards with me. The funny thing was he was a great teacher and he would talk to me while we played cards.”

“I grew up down on East Central Street. So we were right in the center of the Italian section. Growing up, I thought there were only Italians and Irish because that’s all I knew,” Bello said. “And I went to school up the hill at Sacred Heart Academy and the church was across the street, Mount Carmel. The church was the social center. That’s how people met their spouses. My family lived in the same neighborhood. My mother had nine in her family. My father had five. We’d walk up and down Central Street and Shrewsbury Street and everybody knew you. We had the first social media because no matter what I did, my mother would know about it before I came home … I remember looking out my living room window, right down Hill Street, and in those days, when somebody died or it was a feast day, they had the little parades down Shrewsbury Street and I watch them from my window. And they had the band and the woman in the black and the statue going down … My aunt Gladys was very active in the (Christopher Columbus Lodge No. 168 Order of) Sons of Italy and she got my sister and I involved. I became the president of the State’s Sons of Italy. My grandfather was the first one bringing Sons of Italy to Worcester. So we were very involved in the parades and making the floats … I have great memories of it. I am fond of my Italian heritage. I’ve been to Italy eight or nine times, supposed to go again in May but that blew up.”

As one can clearly see, DePasquale and Bello both take great pride in being ItalianAmericans.

“Being an Italian-American, it was this pride. It was this ability to be self-sustaining. It was the ability to take care of yourself, not cry about things, do what you have to do, have faith in God that you’re going to be OK,” DePasquale said. “And, when they spoke about the Blessed Mother or the Christ, I actually thought the Blessed Mother was right there, like she was a tenant or something. She was going to come down and if I was a fresh kid, she was going to yell at me or something. This is how real and strong our faith was. My grandparents instilled in me the faith and honor and all the family values that are really important.”

When talking to Italians about family memories, it doesn’t take long for food to slip into their thoughts.

“My grandfather had this huge garden up on Franklin Street. He had this beautiful grapevine and every day I went up visiting there. We would sit at the grapevine at three o’clock and would have coffee and Italian cookies,” DePasquale said. “So I look up at the hill. I look at the backyard where the house used to be and my grandfather’s grapevine is still standing there strong. And I think of my grandfather all the time.”

“Everybody had a garden, even though they lived in a three-decker and had a postage-stamp (size) yard,” Bello added.

Jonelle Garofoli is 50 percent Italian. Garofoli’s grandparents (on her father’s side) are from Italy and her father’s family grew up off Shrewsbury Street, in a house built by her grandfather, complete with a yard with a big vegetable garden and fruit trees.

Garofoli said the Italian traditions that were passed down to her, especially from her Nana, are very important to her.

“The seven fishes on Christmas Eve. I still cook like that,” Garofoli said. “I still cook the same Italian cookies for Christmas. I give them out to anybody and everybody I can find that needs cookies. I bake a lot and I make limoncello from scratch. I do everything that my Nana did. I picked up a lot from my Nana because I was always with her.”

Garofoli said all families used to be closeknit and everybody knew everyone in the neighborhood.

“They all came over from Italy and settled in the same neighborhood. They knew their parents, and the grandparents and the grand kids. My cousins were like my brothers and sisters,” Garofoli said. “Today, we don’t have the same kind of neighborhoods. There’s a lot of change. You need two incomes. There are two people working. Back then, women that were from Italy stayed at home took care of the house and kids. That was their job.”

Also instilled in her was strong emphasis on being a hard worker and the benefits of a good educa- tion, Garofoli said.

“My father, the eldest of four, had to work because his father died young,” Garofoli said. “He had to quit college so he could support his siblings and my Nana. Education for him is important because he doesn’t want us to have to work like he did.”

Barbara Lucci, who considers herself an “American of Italian descent” (and not an “Italian-Amer- ican”), also said her Italian heritage means everything to her.

“Being an American of Italian descent, I knew exactly who I was,” Lucci said. “I knew exactly what the expectations were. You had to do well in school to succeed. You were supposed to do better than the gen- eration before. But, most of all, you had to be loyal to family, and family was everything.”

Lucci, who is 50 percent Italian from her father’s side, lives in the home that her father grew up in, off Shrewsbury Street, and where his parents lived on the second floor while her grandmother lived on the first floor.

“I still live in that home. So I still feel very connected to the old neighborhood,” Lucci said. “We all stayed together but, now, I don’t think that’s true for everybody. It doesn’t feel there’s a true Italian neighborhood anymore. Shrews-

Jonelle Garofoli stands with her son Lorenzo and daugh- ter Nicolina Pasquale in the cross room of Boucher’s Good Books.

bury Street is the remnants of the Italian-American neighborhood. The farther along that an ethnic group has been here, of course, they’re going to be more assimi- lated, integrated. So I think that’s progress. I don’t see that as bad.”

When it comes to being an American of Italian descent, Lucci said she’s most proud of the way her family has maintained close- ness.

Mauro DePasquale and Carmelita Bello.

SABRINA GODIN

DePasquale and Bello said there is a “disconnect” in today’s ItalianAmericans.

“My mother was home most of the time. She didn’t have to go to work. And then when she was home, my grandmother would help,” DePasquale recalled. “We had a strong community and I think that’s missing. Although it might still exist in certain pockets where there’s new ethnic groups that come in, Italian-Americans are splitting up and moving out.”

“My younger cousins, they identify with the food more than anything. But a lot of the other Ital- ian traditions, they just don’t feel it,” Bello added. “Today’s society, it’s more materialistic. Now, it’s what am I going to make? What am I going to show? What am I going to wear? Where am I going to go?”

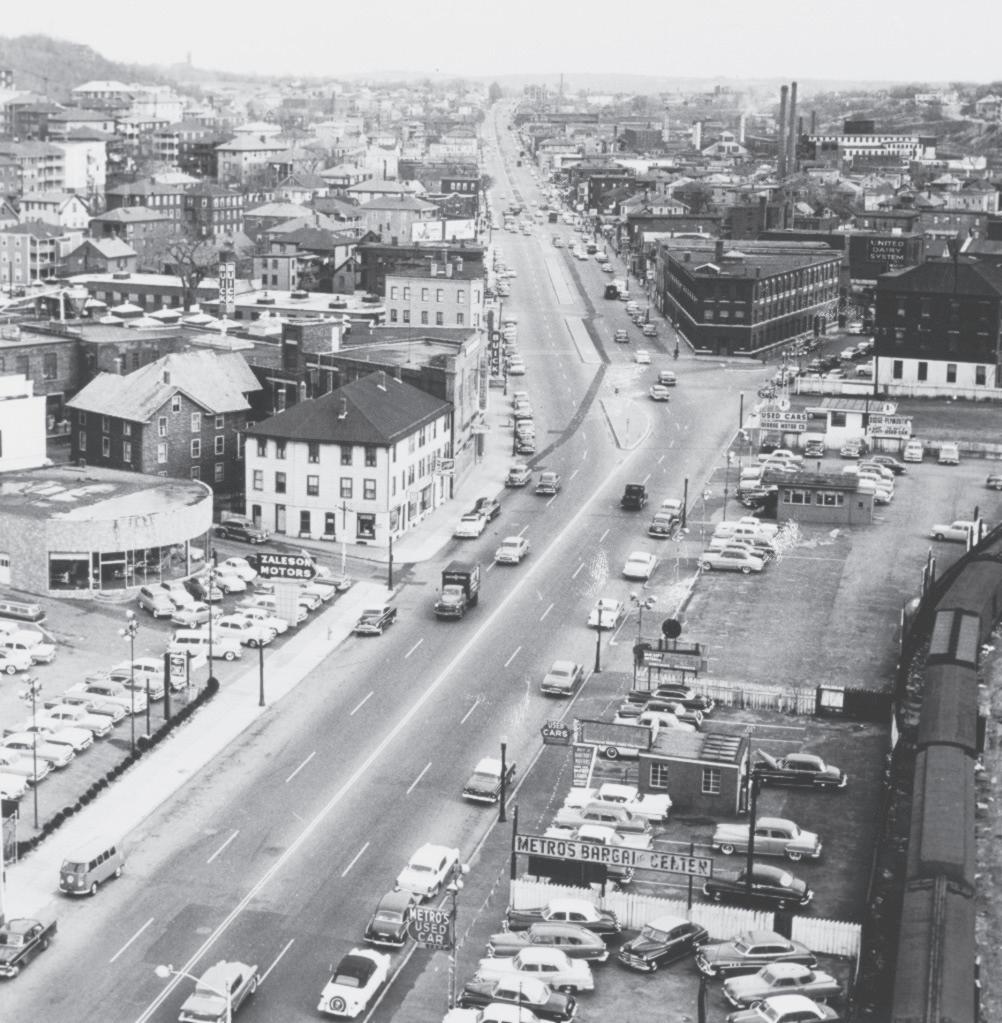

Although the demise of Worces- ter’s Italian-American neighbor- hood probably started with the construction of Interstate 290 many years earlier, it was the demoli- tion of Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church that symbolically meant the end, DePasquale and Bello said.

Bought from the Swedish Baptist Community, Our Lady of Mount Carmel opened its doors on Sunday, Nov. 4, 1906. Twelve years later, the thriving Italian community raised $232,000 to erect “our magnificent Romanesque church, still majestic with its matchless architecture,” according to Capuano in “A Brief History of the Italian Americans of Worcester, Massachusetts from 1860 to 1978.”

“If it had not been for the Mount Carmel Parish, things would have been much harder for early Italians in Worcester,” Capuano concluded. With the church’s closure in 2016 and its subsequent demolition three years later, today’s Italians are now finding out.

On July 21, the City Council voted 8-2 to “file” a motion made by Councilor Sarai Rivera that called on the city manager to work with the local Italian-American com- munity to remove the Christopher Columbus statue and replace it with an “appropriate” one.

While the federal holiday honor- ing Columbus has sparked contro- versy today, no one seems to speak of the racism and violence against Italians documented in our country (but not necessarily in Worcester) leading up to Columbus Day.

According to “How Italians Became ‘White’” by Brent Staples (published Oct. 12, 2019 in the New York Times), President Benjamin Harrison proclaimed Columbus Day as a one-time national celebra- tion in 1892 — in the wake of a bloody New Orleans lynching that took the lives of 11 Italian im- migrants. The proclamation was part of a broader attempt to quiet outrage among Italian-Americans, and a diplomatic blowup over the murders that brought Italy and the United States to the brink of war.

With last year’s demolition of the church and last month’s rally for the removal of the Christopher

Columbus statue at Washington Square, DePasquale and Bello said it’s hard for Italian-Americans in the city not to feel like they are being attacked.

“Columbus didn’t go where he landed to invade. He went with 82 guys. They went on an exploration,” DePasquale said. “Columbus went into the abyss without a map. My grandparents came to this country without a map. They had no idea what they were going to do. And they made a life for themselves for generations of people to follow. So that’s what the Columbus story is about. He might have done some bad things but we are the sumtotal of our history, warts and all.”

“History is made by the people who write it. We have 10 different histories and 10 different perspectives on Columbus. What they’re saying he did, this guy had to be

the most powerful man in the world for him to destroy cultures that they’re putting on him,” Bello said. “Columbus was a brave man. He had a lot of courage and faith in trying to do something different. He had no idea where he was going. You cannot put 21st-century sensibilities onto the 1400s. If you do that, you have to wipe out all of history.”

Unlike DePasquale and Bello, Lucci doesn’t thinks Columbus is a good representative of Italian culture.

“Growing up, Columbus Day was just celebrating being an American of Italian descent. No big deal. But when I learned what Columbus did, I thought, why are we doing this,” Lucci said. “I think we can just have a day to celebrate Italian ethnic pride. I think we can celebrate that without pulling in this guy that exploited people. I’m not that tied to it. People get so upset. I’m not suggesting not celebrate Italian culture, just celebrating without Columbus.”

DePasquale and Bello said there should be some due process and discussion before the Columbus statue is removed and Columbus Day parade is banned.

Left: Singer Joe Cariglia belts out Frank Sinatra songs from the back of a Direnzo Towing & Recovery flatbed truck on Shrewsbury Street in Worcester during the annual Columbus Day Parade Sunday October 13, 2013. Below, Our Lady of Mount Carmel-St. Ann Church on Mulberry Street in Worcester - which has since been torn down due to structural concerns.

“People have to do their research because they can find histories that support Columbus. You can find histories that are in the middle. You can find histories that are against him, just like any other historical figure in the world,” Bello said. “That’s where you have to have the conversation, not just wipe it out. Conversation, not annihilation.”