PEDIATRIC SEATING & WHEELED MOBILITY

Standing Out

How Standing Can Impact Development, Function & Goals for Kids

Marketplace: Pediatric Seating & Mobility

PEDIATRIC SEATING & WHEELED MOBILITY

Standing Out

How Standing Can Impact Development, Function & Goals for Kids

Marketplace: Pediatric Seating & Mobility

CREATING AN OPTIMAL ENVIRONMENT FOR COLLABORATING WITH KIDS AND FAMILIES

For years after I began covering the Complex Rehab Technology (CRT) industry, I thought the goal for every client was mobility, either independent (preferred) or dependent. And I thought the value of mobility was as a means to perform activities of daily living.

As my understanding of mobility evolved, I learned the importance of mobility for mobility’s sake — not just as the ability to brush teeth or eat pancakes, but also just for the joy and freedom of movement. (Cue the dog and cat zoomies.)

Thanks to recent interviews with pediatric-focused clinicians, ATP suppliers, and manufacturer representatives, my understanding of mobility has again taken a leap forward. I now think of mobility as autonomy. And I think of autonomy as freedom.

So many clinicians — including Lisa Kenyon, PT, DPT, Ph.D., PCS (page 4), and Lauren Rosen, PT, MPT, MSMS, ATP/SMS (page 10), both of whom contributed interviews for this issue — have said their goals for pediatric seating clients include giving these children the ability to make more of their own decisions, including the questionable sorts that lead to time-outs. Because autonomy is how we learn. And if seating and wheeled mobility equipment gives kids the freedom to make decisions that become learning moments … great!

In discussing standing regimens for children, Dr. Kenyon pointed out that standing can potentially help with spasticity and range of motion. But she spent just as much time talking about the immense emotional and social impact when kids are able to stand when and where they want to.

In the examples Dr. Kenyon mentioned, the schools, churches, stadiums, etc., were willing to accommodate children who used wheelchairs. The kids could’ve just stayed seated in their chairs. And in fact, even with the ability to stand, kids surely choose to remain seated sometimes. But when you have the ability to stand when you want, then staying seated becomes a deliberate choice, rather than a necessary default.

Ideally, kids who use wheelchairs would have as many of those typical opportunities as possible. Assuming it’s safe, they would be able to stand when they want to. They could remain seated when they want to. They could use their mobility to express their feelings, demonstrate their opinions, and, yes, take a stand.

As we continue to wait for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to make a Medicare funding decision on power standing, we as CRT stakeholders know that personal mobility, including standing, is a basic human right. I hope we soon get to share that hard-won intelligence with our colleagues at CMS. m

Laurie Watanabe, Editor

lwatanabe@wtwhmedia.com @CRTeditor

February 2024

mobilitymgmt.com

CO-FOUNDER & CEO, WTWH MEDIA Scott McCafferty

EDITORIAL

EVP OF HEALTHCARE

MANAGING EDITORS

EDITOR

ART VP, CREATIVE DIRECTOR

GRAPHIC DESIGNER

SALES

VP OF SALES

George Yedinak

Bob Holly Time Mullaney

Laurie Watanabe lwatanabe@wtwhmedia.com

Matt Claney mclaney@wtwhmedia.com

Shannon Pipik

Sean Donohue

INTEGRATED MEDIA CONSULTANT

Randy Easton

Mobility Management (ISSN 1558-6731) is published 5 times a year, March/April, May/ June, July/August, September/October, and November/December, by WTWH Media, LLC., 1111 Superior Avenue, 26th Floor, Cleveland, OH 44114.

© Copyright 2024 by WTWH Media, LLC. All rights reserved. Reproductions in whole or part prohibited except by written permission. Mail requests to “Permissions Editor,” c/o Mobility Management, 1111 Superior Avenue, 26th Floor, Cleveland, OH 44114.

The information in this magazine has not undergone any formal testing by WTWH Media, LLC, and is distributed without any warranty expressed or implied. Implementation or use of any information contained herein is the reader’s sole responsibility. While the information has been reviewed for accuracy, there is no guarantee that the same or similar results may be achieved in all environments. Technical inaccuracies may result from printing errors and/or new developments in the industry.

Corporate Headquarters: WTWH Media, LLC 1111 Superior Avenue, 26th Floor Cleveland, OH 44114 https://marketing.wtwhmedia.com/

Media Kits: Direct requests to George Yedinak, 312-248-1716 (phone), gyedinak@wtwhmedia.com.

Reprints: For more information, please contact Laurie Watanabe, lwatanabe@wtwhmedia.com.

As Lisa Kenyon, PT, DPT, Ph.D., PCS, joined our Google Meet interview, I caught a glimpse of her workstation, which included an elevated platform, perhaps large enough to hold a laptop.

“I’ve been standing for my other meetings today,” she said, taking a seat at her desk. Before our interview even began, Kenyon was demonstrating the value of standing throughout the day.

A timeline for pediatric standing

Kenyon, a professor in the Department of Physical Therapy and Athletic Training at Grand Valley State University in Grand Rapids, Mich., is a member of the American Physical Therapy Association’s (APTA) Pediatric and Education sections, and the American Academy of Cerebral Palsy & Developmental Medicine.

Regarding the timing of a pediatric standing program, Kenyon said, “There are really so many factors that come into it. Ideally, what I want to do is try to enable the child I’m working with to do

the same activities that other children their age do — maybe just in a different way. So ideally, about the same time typically developing children are starting to stand, I should be thinking, ‘How am I going to get standing into the child’s life?’”

Kenyon pointed out that well before children begin to walk, they show interest in standing. “Think about the typically developing infant who’s sitting on your lap, and you’re holding them, and they’re wanting to stand,” she said. “Or you’re getting the infant off the changing table, and they pull all the way up to standing. Your typically developing child is really doing a lot of supported standing through the help of an adult or their couch or their crib before their first birthday.”

A standing regimen could be helpful to a child’s development even if the child is expected to eventually stand independently. “We know that for the child who’s going to be a little bit delayed in their mobility, some standing is still important,” Kenyon said. “We may not necessarily do it with as much equipment. We might do more

supported standing: Standing at the couch is a therapeutic activity for those children who maybe are just going to walk a little later.”

When children are going to be more significantly delayed in learning to walk — around age 2 or older — “I begin to think about equipment,” Kenyon said. “And for those who aren’t going to be walking, I begin to think about it even earlier, because again, I want to try to get them up and standing when their typically developing peers would be. So about 12 to 14 months of age, ideally.

“For children who have severe cerebral palsy — children who are Gross Motor Function Classification System Level IV or V, or other conditions that present similarly and are just not cerebral palsy — we should be starting standing by about 12 months of age.”

Kenyon added that before going too far into a conversation about standing, she checks in with the child and family. “I also want to make sure that these are, of course, activities that they want to do or their family wants to do. Sometimes I’ll talk to therapists, and they’ll say, ‘I want them to be able to do this.’ I ask, ‘Does the child want to do that?’ You want to make sure the child’s on board.”

While there isn’t substantial information yet on the benefits of standing for young children, “For the older child, we have good evidence to suggest that standing programs — if we pay good attention to our dosages — can have an effect, if we reach a high enough threshold with those doses,” Kenyon said.

For example, enough minutes of supported standing can impact bone mineral density, Kenyon said, adding, “It can also help hip stability, particularly if we have them in a certain degree of total bilateral hip abduction, which means having their legs apart. Also, it can help range of motion, mainly of the hip, knee, and ankle, and even with spasticity. We know that those things are going to be helped if we can get these appropriate doses. There are different doses for different outcomes.”

Standing is also the gateway to performing a range of activities of daily living (ADL), including self-care activities.

“We do so many things in standing,” Kenyon pointed out. “We stand in the morning to get out of bed. We stand in front of the mirror to do our toothbrushing or fix our hair. We stand to do ADLs in the kitchen — cooking and things like that. We stand to get something off of a high shelf or out of the refrigerator. I think we forget about standing as a function.”

What about contraindications for pediatric standing?

“First of all, especially if a child hasn’t been standing, I want to make sure that it’s safe, especially as a child gets older,” Kenyon said. “They may have brittle bones. They may have osteoporosis, and I

need to be very, very careful about putting them right into a standing position. I usually work very closely with the medical team, that child’s physician or orthopedist. I’m making sure that it’s safe for the child to stand. If, for example, it’s an 11-year-old girl who’s never stood before, I’m going to really look at making sure it’s safe for her.”

And during the standing process or trial, Kenyon keeps observing. “I want to look at the range of motion. Can they tell me if they have pain, and if they do stand, do they seem to have pain? Do they have orthostatic hypotension, where they come into standing and they get faint because they’re just not used to having their blood needing to pump in that direction? We tend to think about those things with adults, but not necessarily with children as well.

“If we aren’t careful, we could cause a tendon to rupture, or a fracture, or we could have a child pass out if we’re not recognizing the orthostatic hypotension. So as much as I want to get these kids standing, I have to do it through the lens of safety and what’s appropriate for them in their situation.”

Kenyon also asks about orthoses. “If the doctor told the child’s parents that [the child] shouldn’t be standing without his ankle-foot orthoses on, then I’m going to make sure he’s standing with the ankle-foot orthoses in any stander that I provide for him, whether it’s a power wheelchair standing device or static stander.”

No matter how eager the child or family might be about a standing regimen, Kenyon emphasized the need to put safety first. That process could mean progressing to a standing position more slowly, in stages.

“Definitely we would try different gradations,” Kenyon said, in possibly taking a more measured approach. “If the child’s small enough, I may just try having them supported by me while standing. I want to make sure that I’m doing these things in ways that are safe. So even if a family is [very enthusiastic], I’m going to put the brakes on until I determine in my professional judgment that it’s safe. There’s not really a list of things that I’m looking for. It’s a pattern that comes together, and as a licensed professional I have an obligation to ensure safety.”

Current standing equipment choices include static standing frames, standing frames that can be propelled by the child or caregiver, and power standing functions on power wheelchairs.

For very young children, there are additional early-intervention choices, including the Permobil Explorer Mini and ride-on toys modified via the GoBabyGo program.

The Explorer Mini, with straddle-style seating, allows its young riders to either sit or stand while driving. “It provides them with some support,” Kenyon said of the Explorer Mini. “The alignment isn’t going to be quite as well controlled as in a device that was meant for you to be standing for a long periods of time.”

While GoBabyGo vehicles — switch-driven devices created by adapting power ride-on toys — typically are driven with the child seated, some vehicles have been modified to promote standing.

“I think there’s a lot of different ways that we can get standing into a young child’s life,” Kenyon said. “There was even a project done, I believe it was by Dr. Sam Logan, where they adapted [ride-on power toys] so that the child had to be standing for the device to go.”*

Static standing frames can offer the physical benefits of standing — bone mineral density, range of motion, etc. — though some ADLs “can be difficult to do in a static stander, but we can maybe think about different ways to be mobile in the standers,” Kenyon said. “There are standers that have big wheels that children can push, if they’re able to do that. There are power wheelchairs that have a standing feature attached to them. We call them power wheelchair standing devices, and they convert between sitting and standing and can be driven in either position.”

Standing also expands the child’s literal reach and related abilities, Kenyon said. “Sitting really restricts somebody to just functioning in a horizontal plane. There is some evidence that suggests that short bursts of standing during the day or longer bursts of standing during the day with the children in a static stander actually are helping to contribute to light physical activity and are decreasing the sedentary behavior of just sitting. I think that is really an exciting thing.”

While the physical benefits of standing are significant, Kenyon also praised its potential social and emotional benefits.

“They can see different things,” she said of the change of positioning for kids. “Some of the children that we’ve worked with who used the power wheelchair standing devices have talked about ‘I could go to the museum, and I could stand and see something, I could go to the racetrack, and I could stand and see just like everybody else.’

“This is something that we don’t necessarily think about all the time — standing as a sense of belonging, and the children who can transition themselves between sitting and standing using the power wheelchair standing device. If they’re in a church and someone says, ‘Okay, everybody stand,’ they can make that decision if they’re going to stand. If they’re at the baseball game or the hockey game or at school and they’re doing the Pledge of Allegiance or the national anthem, they can decide to stand. We’ve had a lot of children tell us how much that makes them feel like they belong in the community rather than setting them apart.”

Kenyon is a fan of the autonomy that power standing wheelchairs can offer young wheelchair riders. “One young man who went to a concert for a very popular Christian band was so excited because he had been to concerts like that before, but he couldn’t stand. But this time when they said, ‘Everybody stand,’ he could stand up. And then when they said, ‘Okay, you can be seated,’ he could sit back down. That was just so exciting for me to hear that he felt so in touch with that spiritual activity because of a piece of equipment.”

Sitting really restricts somebody to just functioning in a horizontal plane

— Lisa Kenyon

That ability to move from sitting to standing on demand can be so important to families, Kenyon added.

“In one of our qualitative studies about power wheelchair standing devices, one of the moms — and I thought this was just so insightful — said that with the power wheelchair standing device, [her child] can stand when he wants and where he wants,” she said. “He doesn’t have to say, ‘Could you excuse me for a second while somebody transfers me into this other piece of equipment?’

Ultimately, greater autonomy for children at any and all ages can be empowering and priceless. Kenyon recalled working with a gifted, ambitious student who needed to take high school chemistry — in a classroom with elevated lab tables — to achieve the college goals she’d set for herself.

“The power wheelchair standing device enabled her to be able to take chemistry and get an A,” Kenyon said. “I’m sure that the school would have been required to make some sort of modification, but she liked that they didn’t have to. She could stand.” m

*Study: Standing Tall: Feasibility of a Modified Ride-On Car That Encourages Standing, by Samuel W. Logan, et al, National Library of Medicine, Jan. 2019. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/30557294/

Permobil® M Corpus VS Comfort Company Acta-Embrace cushion

BodiLink™ laterals

Comfort Company Acta-Embrace back support

BodiLink™ headrest

TiLite™ Twist

SmartDrive

SpeedControl Dial

Natural-Fit, The Surge handrims

For those new to seating and wheeled mobility, a seating clinic evaluation can feel mysterious and intimidating. Parents might be still processing their child’s new diagnosis or recent injury, and might still be struggling to understand the months and years to come. The clients themselves may be frightened, shy … or, when those clients are younger, just more interested in Bluey or Paw Patrol than talking to the clinicians, ATPs, manufacturer reps, and other professionals who’ve gathered to collaborate.

Against this backdrop, what can seating team members do to encourage a successful evaluation?

Matt Lee, ATP, CPST, serves families at Cook Children’s Home Health Custom Mobility in Fort Worth, Texas.

Asked how he prepares for an upcoming assessment — perhaps by reading up on the basics, such as the child’s name, age, diagnosis, presentation — Lee said, “I try to walk the line between being the prepared Boy Scout and knowing the lay of the land we’re going

into. But I’ve also noticed that it can almost be a little jarring when you seem to know everything going on about the family before organically finding out from them.”

Since Cook Children’s is affiliated with a hospital system, Lee noted that he does have access to information such as diagnosis, weight, and height — “stuff that’s helpful for knowing what type of equipment we want to be bringing. So we’re bringing something appropriately sized, but also knowing their background, if they’ve had other orders in the past. That’s something we want to be asking about, especially for pediatrics.

“You could be getting [a family] new to this whole world, versus [a family] that says, ‘We’re just growing, we just need a new size.’ Then we’re finding out what’s worked and what isn’t working. We try to do a little information gathering so we’re bringing something that’s appropriate to the trial: ‘No, we don’t need a one-arm drive because they’re able to use both of their arms for propelling.’ Then I don’t have a truck loaded up with a million things. I’m trying to make sure I’m bringing something more relevant.”

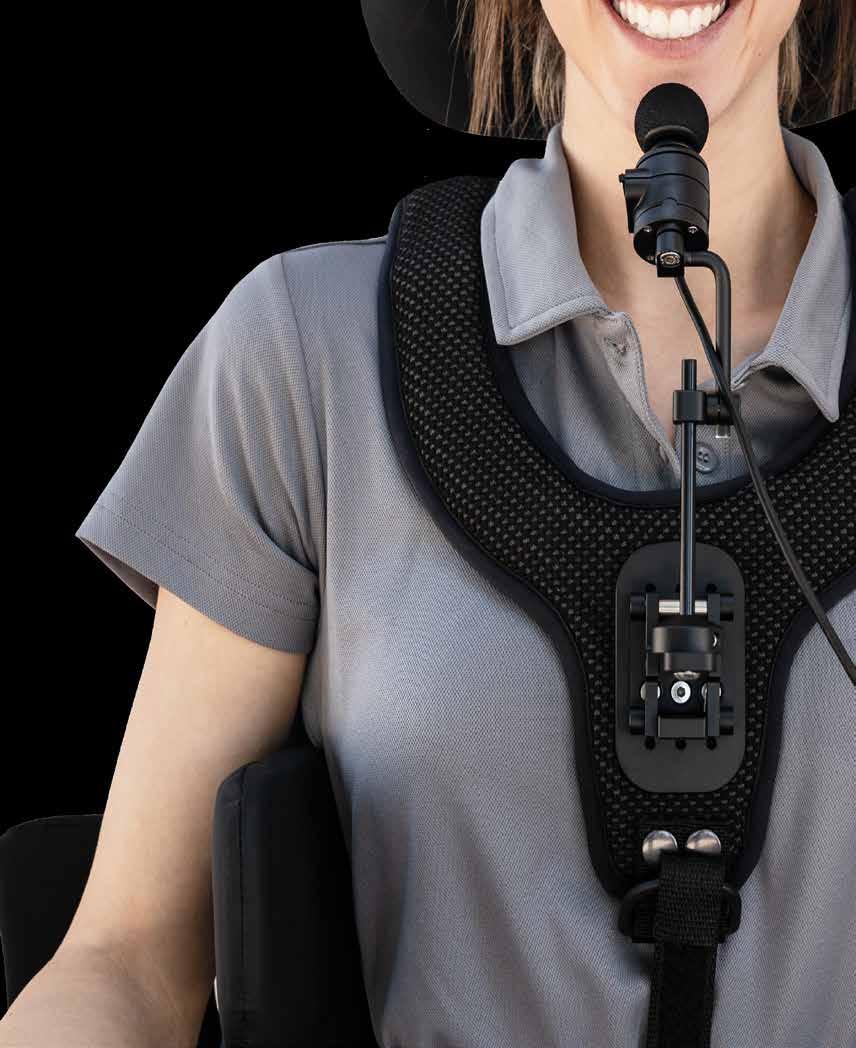

Unobtrusive and discreet, the Vigo™ is a wireless, proportional head control that allows drivers to control their power wheelchairs and other devices with subtle and intuitive head movements.

Learn more

Daniel Craig Jr., ATP, spent more than 23 years at Miller’s Rental and Sales, where he served as Director of Adaptive Technologies, among other roles.

Now the Pediatric Account Manager for Leckey and ZIPPIE at Sunrise Medical, Craig plays a different role at seating evaluations.

Q: What is your main responsibility during a clinic evaluation?

Daniel Craig Jr.: Our responsibility is to be the product expert, to have a deep understanding of the product’s capabilities and limitations, and to offer solutions. We are there to support the ATP and clinician to get the best outcomes for the client. I also assist by bringing samples that we can use during the evaluation. That way, we have options to try.

I like to work together as a team with the ATP, clinician and family/caretakers. This normally results in the best outcomes. I want everyone to feel comfortable using the products that are being recommended.

Daniel Craig Jr.: I agree with that. Most of us are also ATPs and have varying backgrounds. My background was in custom seating, and I worked with those that had severe deformities. With the experience I have positioning those with mild to complex needs, I could be used more during evaluations to discuss systems that would best fit the client. I could also bring samples to help illustrate what those possibilities are.

I have my ATP certification and worked on the provider side before working for Sunrise as a representative. While working for Miller’s, I was also a fabrication technician, where we built our own custom seating from a piece of wood and foam. This has given me a lot of knowledge on how to position clients to achieve their goals.

So what information am I normally looking for when coming in to do an evaluation? I’d like as much as you can give me. I can offer up solutions when I can get a description of how the client presents — more than just the diagnosis. [Do] they have a kyphosis, lordosis, curvature of the spine, rotations, obliquities, and is it reducible or non-reducible? If we know what some of the goals might be — dependent/independent mobility and if it is a manual/power frame to achieve those goals — I can bring the appropriate items.

I am focused on the best outcome for the client, making them as functional as possible while also providing support where they need it. The solution should align with the team goals.

Q: What’s the importance of building trust with the team?

Daniel Craig Jr.: For me, long-term rapport is the support that the rep can offer to the team. It is that ongoing support for our products. If the rep has a good rapport with the ATP and clinician, this will give the rep a great start with the family and client. Knowing that we fully support and stand behind our equipment will give them confidence in their decision. The families that we get to interact with appreciate when you support the equipment you have, and know that you are there to answer questions and available to assist the dealer with any questions/concerns that may arise.

Q: Can manufacturer reps be great resources for seating teams?

Being part of the evaluation allows me to learn as well. I do not know everything. I enjoy learning and then having the ability to share that knowledge with others so that they can benefit from it as well.

Q: During your career, how have you made families more comfortable?

Daniel Craig Jr.: First and foremost, treat everyone how you want to be treated. I start with a number of questions with every client: Is this their first piece of equipment, or are they heading into their third chair with seating? If it is the first equipment evaluation, it can be overwhelming. There is a lot of information that we are providing them so that they are confident with decisions that are being made. Because they will be on information overload, we just need to be a little more patient with them.

In evals, I always try to keep the mood upbeat and positive. The energy in the room is important. I make sure that everyone is involved in the conversation and that they know their input is valuable. Everyone should feel included, and no one should feel left out.

If it is the first equipment evaluation, it can be overwhelming — Daniel Craig Jr.

Depending on what equipment I am showing at the eval, I will have a mannequin that I bring with me. This normally intrigues them and makes the equipment more inviting.

If they are new to seating, they will have a lot of questions. Listen to what they are asking, and translate that into solutions that you can offer. The parents normally have a vision of what they are looking for and are looking to us to make that vision come true. We need to bring those expectations out so that we can best make sure what we are offering is in alignment with their expectations.

At the end of the evaluation, I want them to feel confident about what has been discussed. If they leave with more questions then what they came with, we did not meet our goals m

Complex Seating. Simplified.

Fit a custom molded back in one appointment

Single tool adjustment

Completely ventilated custom seating

HCPCS Coded E2617 and E2609

Demos available

Beat the heat with for fully ventilated custom seating! StimuLITE ®

Back Kits available with a full range of sizes, shapes, padding/covers and mounting options.

Lee said the three “crucial” facts to know ahead of time are the child’s height, weight, and positioning needs — which he uses to determine what equipment to bring.

Then he grinned. “Although the Boy Scout in me is always, ‘And throw this other thing in, just in case.’”

Lindsey Rea: Know the possibilities

Lindsey Rea, ATP, is currently a Commercial Product Manager for Permobil. But for 21 years, Rea worked as an ATP provider who specialized in pediatric seating.

As an ATP going into a seating clinic eval, Rea said she wanted to know about possibilities, starting with the physician’s thoughts on the type of mobility the child could be capable of.

“A lot of times, the doctor would lead and say, ‘Hey, let’s try power [mobility]. I’m not sure, but I know I want them to have something. Do they have the potential for independent mobility?’

“So that’s probably the first thing that I want to know from the physician: Is there a goal, even if it’s for future independent mobility?”

If the goal is independent mobility — now or at a future time — Rea said the next step is understanding what that could look like.

“Where is this piece of equipment going to be used?” Rea asked. “Is it going to be used at school? Is it going to be used for community access? What does the living environment look like? If you have a tri-level home, [power mobility] is probably not feasible. But if a goal is still to use the chair outside in the neighborhood and to interact with friends, we have to look at that.”

Rea also considers who to involve in the assessment process.

“As the ATP, you want to provide input, especially because the ATP really has that connection with all the different components,” Rea said. “The ATP is in touch with the parents. They’re in touch with the doctor, with the different therapists. That’s

how I would start: What are the goals, and where is it going to be used for mobility?

“And then I start incorporating the team right there at the evaluation. You always want that therapist to be there, because if they’re going to write that justification, they have to know what the equipment is like. It’s a collaborative approach, a team approach. I didn’t necessarily include a speech therapist, but I always considered doing so because so many kids use communications devices. Or if we’re looking at power mobility, my first question was always, if it wasn’t obvious, ‘Do you use a communication device?’ Because if the speech therapist has already figured out that access site for communication, why don’t we use that for mobility, too?”

Rea also wants to know equipment history — so, she wants all Pokemon cards out on the table, so to speak.

“I want to know about existing equipment,” she said. “I always want to know all the pieces of adaptive equipment already being used so we can take that into consideration. I would say if they have existing equipment, bring that to the evaluation.

“But when we look at mobility specifically, we want to know the vehicle. Bring your

I’ve also noticed that it can almost be a little jarring when you seem to know everything going on about the family before organically finding out from them — Matt Lee

vehicle that you’re driving. Because whether [the equipment] is power or if it’s manual, how is it going to fit in the vehicle?”

Matt Lee: Avengers, Assemble Lee has seen good results in inviting other stakeholders to clinic: family members, caregivers, nurses, siblings.

“Sometimes,” Lee said, those other stakeholders “are pointing out things that parents don’t even recognize. I’ll say it’s like we’re putting together the Avengers or A Team. We’re getting the whole team together to give input, because when I was a tech, there were a couple of times where an ATP did an eval, and — it wasn’t really their fault, but they were only there with Mom, and Dad wasn’t present. A lot of times, people will say, ‘We’re on the same page, I’ll defer to Mom and we’ll make it work.’ But there have been times where we rolled into a room and the other parent or family member will say, ‘How is that going to work in our house?’ We have this problem because we didn’t have that quick conversation with all the people involved. We now are having to go back to the drawing board to figure out this equipment and make it right for the family.”

Rea estimated that when she worked as an ATP, 98% of her clients were children.

“My initial approach was: ‘I don’t have any

As Program Coordinator at the Motion Analysis Center, St. Joseph’s Children’s Hospital of Tampa (Fla.), Lauren Rosen, PT, MPT, MSMS, ATP/SMS, has a sizable office.

Rosen needs that space for her array of demo wheelchairs — power, manual self-propelled, manual tilt. And her clients — some of whom are experiencing independent mobility for the first time — need room to spin, turn, and move.

But some of the space in the office is reserved for conveying a message just as important as the need for mobility.

Barbie, Ken, Sarah, and Aaron Rosen collects Pez dispensers, many of which live in her office. Large stuffed animals lounge in and among demo chairs.

Shelves hold Barbie and Ken dolls, all in wheelchairs, and three “Becky” dolls, also in wheelchairs. The original Share a Smile Becky — the first Barbie-franchise doll to use a wheelchair — sits atop a tiny Stimulite honeycomb cushion, supplied to Rosen by Supracor.

“Mattel made a [sitting] snow skier Barbie, so she’s on the same shelf with the Beckys,” Rosen said.

On a top shelf sits an American Girl doll in a wheelchair: “Her knees do not bend, so she has elevating legrests,” Rosen explained. A teddy bear sits in a My Life wheelchair, My Life being the Walmart equivalent of the American Girl franchise.

“I’ve got the My Life amputee doll that’s dressed like a gymnast,” Rosen said. “There’s a teddy bear sitting by itself: That’s a Sarah Reinertsen bear. Sarah Reinertsen is a Paralympic athlete who did a lot of triathlons, and she came up with Sarah Bears. She’s a single above-the-knee amputee, so my Sarah bear has the same [prosthetic limb] as hers. I was at a triathlon out in San Diego, and she signed it for me.”

Rosen has two remote-controlled toys modeled after extreme athlete Aaron Fotheringham’s ultralightweight wheelchairs, plus the Fotheringham Hot Wheels wheelchair. She’s especially excited about her newest Playmobil set: “I just added a school bus that has a ramp and has a kid in a wheelchair that you can put into the school bus.”

Her collection is more than 20 years in the making. “I was really excited when I got the [Fisher-Price] Aidan Assist,” Rosen said of the action figure who’s an EMT in a wheelchair. “That was the first boy in a chair that I had. So I was very excited when I added him, and then most of the Playmobil characters seem to be boys in wheelchairs.”

“She has a blue chair, and you have a blue chair” Rosen described her office — where dolls and action figures in wheelchairs share space with Pez dispensers, stuffed animals, and other toys

— as “a wonderland” with a clear message.

“The room just shows how normal they are,” she said of the wheelchair toys. “They’re just another set of toys. I think it does take some of the stigma away, that I’ve got a shelf of Pez dispensers, and right under that a shelf of Barbies.

“I do point them out sometimes: ‘Do you see there’s a Barbie in a chair? She has a blue chair, and look — you have a blue chair.’ But they’re not there specifically for that reason. They’re just there for normalcy. They’re things that bring me joy.”

They bring joy to the children she works with, too. Rosen routinely hands out toys to her clients.

“I offered her a Squishmallow,” Rosen said of one recent young client. “It was time for her to leave. We were delivering her wheelchair, and she was having so much fun in my office that she clamped down on her wheels and was crying and was not leaving my office.

“I said, ‘If I give you a Squishmallow, will you leave?’ No. I must have tried five different toys, before I said, ‘How about a Barbie in a wheelchair?’ That got her to let go of her wheels.”

Rosen laughed. “That’s how much fun I am. Kids get very upset when they have to leave.”

Bonus content: When Barbie went to seating clinic Seat width! Center of gravity! Camber, elbow flexion, footplate placement!

In a Mobility Management exclusive, Lauren Rosen provided a comprehensive “telehealth seating evaluation” for Barbie and her ultralightweight rigid chair. “I would give her some seat slope, but I’d move those wheels forward,” Rosen said in addressing handrim access. “I would definitely change that footplate; it’s got to be higher.” m

Read all about it: http://tinyurl.com/ seatingBarbie

expectations,’” she said. “I have no agenda. I’m not pushing anything or any specific equipment. I want to go in there open and then have the conversation.”

She also respected goals that parents had set. “The biggest thing with families has been accepting their goals,” Rea said. “My message to them is ‘We are not taking away your goal.’ I would validate their desire and their goal. If they said, ‘We want our child to walk,’ I said, ‘So do I. And when they start walking and they don’t need my equipment anymore, I’ll celebrate with you. We’re not replacing your desire to have your child walk. We are meeting your child where they are right now and supplementing their mobility.’

“We are augmenting what they have so that they can experience what every other typical child has, whether it’s running with friends or interacting with their peers. We’re meeting them where they are right now so that they’re not missing out.”

Rea added that therapists often thanked her for those affirmations. “Because a lot of times, therapists see the [parents’] fear. Even if you know that the child’s not going to walk, you can’t squash those parents’ hopes.”

In the end, providing the best possible pediatric seating and mobility is a challenge.

“It’s called Complex Rehab Technology, not simple rehab technology,” Lee acknowledged. “It is tough trying not to be too cookie-cutter with our prescriptions, but at the same time, for the sake of efficiency and turnaround, not spending a month trying to

My message to them is ‘We are not taking away your goal.’ We’re meeting your child where they are right now so that they’re not missing out

— Lindsey Rea

research and dive too deep into things only to come back to ‘This would have worked fine, and we didn’t need to go down the rabbit hole.’

“We’re trying to predict what the next three to five years are going to be for this kid’s life — not just growth, which is kind of standard, but are there surgeries coming up? Are there procedures they’re going to be doing that will greatly affect their positioning and function? Are we building that into the chair, or do we at least know that further down the road, we can do modifications that we need?”

Rea acknowledged the stress that families can feel and works to make sure that they are comfortable with the technology being considered.

“Some of the technology out there is so advanced that you have to look at the caregiver, too,” she said. “Because if they’re intimidated by it or if they don’t understand it, it’s going to be abandoned. You have to look at the caregivers to see how if they’re able to use it. If it’s a single-switch driving system, and that switch is near the child’s leg or something like that, do you have caregivers that are comfortable adjusting that? If not, you’re not going to have success.

“There are situations where I have had therapists saying, ‘We need to do this with power,” and I can see the hesitation from the parents. They’re afraid of the equipment. And they’re not going to put their kid in the equipment, either.

“Technology abandonment is such a frustration that I would rather, from an ATP standpoint, not push anything.”

Lee agreed. “The [wheelchair] real estate is just so small for putting on straps and harnesses. Then you’ve got to figure out another way to attach the control device, and then making sure Mom, Dad, the caregiver nurse, whoever, are able to still take everything apart. You’ve added a whole bunch of complexity. And so the other big thing is avoiding equipment abandonment because it’s gotten too complicated.”

“I always said I’m a terrible salesperson because I’m not going to push anything,” Rea said. “I was very realistic with my approach and very practical, whether it was strollers or power or manual wheelchairs — even standing frames and gait trainers. Because I want you to enjoy your kid, too. That’s so important.

“Sometimes, parents say, ‘We took a break from therapy.’ I say, ‘Good for you. It’s okay.’ I think with adults, we look at how do we make them independent? That might not be the case for kids. Sometimes it’s ‘How do we allow you and everybody to enjoy quality of life?’ I think that’s the biggest part of my approach. It was ‘What’s the quality of life for everybody involved?’

While seating professionals might be envisioning the freedom of independent mobility or standing or gait training, Rea said she sometimes instead thinks of bath chairs “and being able to enjoy giving your child a bath. I think of beds, and the gift of sleep. I think about how important that is. It’s the same thing with mobility. I want that to be a goal. I want them to all have quality of life.” m

Available in both folding and rigid designs, the Freedom Designs NXT was created to meet a family’s need for a quick, easy, lightweight, and transportable tilt-in-space wheelchair without sacrificing quality and durability. The NXT is quick and easy to adjust to continue to meet kids’ needs as they grow. Seat dimensions are available in 10" to 20" widths by 12" to 20" depths. Most sizes grow 2" in width, and all sizes grow up to 4" in depth. Each NXT includes the Freedom ”Future Fit” program that provides the parts necessary to grow the width of the NXT one time during the life of the frame, not including the NXT SE frames.

Freedom Designs

(800) 331-8551

http://freedomdesigns.com

EPiC (Effortless Postural Control) Seating is a postural management system that allows the introduction of movement into a wheelchair seating environment. The system provides the ability to change positions for function while maintaining control of the pelvis, thus mitigating the opportunity to introduce shear. The segmented back support system provides stationary pelvic support and a moving thoracic segment. The system also incorporates an anatomical pivot point, contributing to improved stability. All secondary positioning supports attached to the thoracic segment move in unison with the body, reducing the frequency of repositioning events.

Stealth Products (800) 965-9229

https://epic-seating.stealthproducts.com

The award-winning MPS Mini Maxx is an innovative, highly adjustable system that combines a power standing function with a full range of power positioning solutions. Available exclusively on the ROVI X3 and A3 bases and accommodating 12" to 17" seat widths x 12" to 17" depths, this compact design offers smaller clients a combination of independence, function and accessibility, along with a tremendous amount of built-in growth potential. The superior positioning and comfort of this system are completed with the award-winning Matrx MINI Seating products, designed to fit the smallest clients of all shapes and sizes.

Motion Concepts (888) 433-6818

www.motionconcepts.com

The Explorer Mini is a regulatory cleared, powered mobility solution that facilitates self-initiated movement and early exploration for young children 12 to 36 months of age with mobility impairments. Designed to support development, the Explorer Mini is an ergonomic device with multiple weight-bearing surfaces to help promote safe, stable, upright postures while providing opportunities to improve strength, endurance and postural control. The Explorer Mini has a maximum user weight of 35 lbs. for children as tall as 39". A 3-mile driving range provides plenty of opportunities for exploring and keeping up with peers.

Permobil (800) 736-0925

www.permobil.com/en-us

The Squiggles+ stander offers up to 60° of bilateral hip abduction, making it now achievable with the added benefit of a measurement gauge to monitor and aid repeatability. Designed to encourage a child’s socialization and interaction at eye level, this stander provides unsurpassed support, adjustability, and easy storage for caregivers. Additionally, the Squiggles+ stander promotes proper alignment in the child’s hips, knees, and feet, ensuring that pivot points are in line with the hips.

Sunrise Medical (800) 333-4000

www.sunrisemedical.com

The custom-moldable Savant head support now contains 25-percent softer gel and stiffer lower support arms. The cool, lightweight support is easily shaped by hand. The optional Carbon Cover features a durable, low-shear material that reduces friction from head movement. The cover can easily be wiped with a cleaning solution or disinfectant to maintain a clean, low-profile head positioning device. Quick-release buckles hold the headband in place. High lateral pads give effective lateral flexion control, while mid lateral pads are shaped for comfort behind the ears. Sub-occipital pads provide extra support below the occiput. The included headband can be used for additional anterior support.

Symmetric Designs (800) 537-1724

www.symmetric-designs.com