17 minute read

Visibility—A Celebration of Black History

African Americans In Film

By Sean Champa ‘23

Black History month may have different meanings for different people, but it is primarily a celebration dedicated to focusing on achievements made by black people and the adversity they faced. An industry that African Americans have made great strides in but has been the culprit of many stereotypes created of them is the film industry. Some of the earliest films and representations of African Americans were The Gator and a Pickaninny (1903), in which a fake alligator eats a black child and The Watermelon Contest (1908). These films portrayed many of the racist stereotypes already seen in literature and minstrel shows at the time. These stereotypes would continue, used to justify racist ideologies and over time they would change to fit cultural contexts. At the time, Hollywood rarely made films portraying African American life and culture with humanity. Because of this, many African American entrepreneurs went into filmmaking in order to fix the negative portrayals. Bill Foster is one such entrepreneur who founded the first black film production company in 1919, the Foster Photoplay Company. Oscar Micheaux was a noted novelist who founded the Micheaux Film and Book Company in 1918. Oscar Micheaux went on to create forty-three films over the three decades. These film companies created “race movies,” movies that featured almost all-black casts and were marketed to black audiences.

On the other hand predominantly white-owned studios hired white actors to play African American characters using blackface. Warner Bros.’ The Jazz Singer (1927) was one such film. The main character, Jakie Rabinowitz, a jewish singer, performs in blackface. He wants to be a jazz artist but his father wants him to become a cantor. In his nonreligious persona his performances draw from the blues tradition and black spirituals, an example of Hollywood taking advantage of black expressive culture. Beginning at the end of the 1940s, following World War II, a heightened sense of liberalism in American society led to changes. Films about race and power began to be produced by major studios such as Intruder in the Dust (1949) and Home of the Brave (1949). By the 1950s the “separate cinema” had ended and African Americans no longer had creative control over their movies. Hollywood looked for black talent but continued their racist, exclusionary policies. The civil rights movement brought about social change which influenced the box office. The first African American movies stars such as

Sidney Poitier and Dorothy Dandridge emerged. While still somewhat problematic the films they performed in challenged society’s views on race and social roles.

Later in the 1970s, Hollywood created a narrow representation of black culture. While there were black casts, many of the films were written and produced by white men who depicted black men as drug dealers and killers. Hollywood continued to create stereotypes of black people that could easily be taken as factual. New, young, and bold directors such as Spike Lee began to change the status quo through film. Lee’s directorial debut Do the Right thing (1989), tells a very real and sometimes sad reality of black life. A diverse neighborhood clashes with each other and different opinions become racial. The character Radio Raheem is portrayed as a strong African American who finds a love in Afrocentrism and black power. He is a justiciar to represent the people. His blind love towards his fellow brothers and hate towards his enemies is what eventually gets him killed as police choke him to death.

African American films have been through many different phases throughout history. While movies have been created in a way that misrepresents African Americans, many have also been directed and produced by bold black entrepreneurs and visionaries who sought to change society’s ideas of race. The resilience of so many African Americans has shaped and changed the film industry for a brighter future.

African Americans and the Fight for Education

By Austin Kim ‘23

The period of Reconstruction is often thought of merely as the time the US rebuilt physically and intellectually as a unified state. However, the symbolism of this period for the African American population is commonly overlooked. The ability to become educated became the spirit of development to the Black population during this time.

Prior to the Civil War, African Americans had very little access to schools and opportunities compared to their white counterparts. After the Civil War, however, African Americans were no longer denied access to these public services and were able to rebuild their lives. One of the first goals the African-American population set was becoming educated. They faced various challenges achieving this goal, though.

The first primary setback was a lack of teachers. During the Civil War, there were a few African Americans that were briefly educated by being in the army and a few that were able to learn how to read and write so that they could read the bible in secret. Many of these people became teachers for the Black students, but many of them were still underqualified. Luckily, many teachers from the North began teaching at the partially established schools throughout the South. Many of the teachers taught temporarily and eventually returned to the North, but more African American teachers learned how to teach better before they left.

Another set back was facilities and locations to host the schools. Open land to start up new schools (along with funding) wasn’t available to them, so many communities improvised and implemented schools into churches, town halls, and even abandoned buildings. One of the most famous examples is Tolson’s Chapel. Established in 1866 in Sharpsburg, Maryland, Tolson’s Chapel became the first school-church combination throughout the entire town. As time progressed, African Americans in Sharpsburg turned to various government-run bureaus, with the most notable one being the Freedmen’s Bureau. Eventually, even more Northern and Government-based organizations provided teachers and funding for more school facilities. When there still needed

to be more schools, even more African American churches were turned into schools throughout the town. Eventually, countless African American children became students and were educated. It got to the point where adults wanted to become educated as well, which leads into my last point.

Many adults wanted to become educated as well in order to read the bible (they were prohibited before), get new jobs, and eventually combat the systemic racism that still existed. Systemic racism was able to thrive because of the widespread illiteracy among the Black population. They weren’t able to read documents and weren’t able to know what they were signing if it was something like a contract or waiver. Therefore, by learning how to read, adults could become independent and get jobs that they’re passionate about. Therefore, many Black schools across the South started Night Schools that many African American adults attended. They were able to become literate, take over jobs, etc.

Overall, the Reconstruction was a time of movements for the African American population. Many across the South took advantage of new opportunities by becoming educated to live independently and reduce instituted racism. By becoming at least literate, African Americans were able to take job positions, read the bible, and bond as a community.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

By Tilly Lapaglia ‘23

Born in 1825 to free African American parents, Frances Ellen Watkins was raised in Baltimore by her aunt and uncle. Her uncle William was an abolitionist and educator who ran the Academy for Negro Youth, which Francis attended and received a rigorous education that shaped her political, religious, and personal beliefs. After leaving school at 13, she helped slaves escape through the Underground Railroad and wrote frequently for anti-slavery newspapers, and soon became known as the mother of African American journalism.

After working as a teacher for a time, Harper was exiled from Maryland in 1854 because of new slavery laws stating that Black people who came in through the northern border of Maryland could be sold into slavery. This, along with the tales she had heard of slaves escaping the brutality they faced, marked the beginning of Harper’s activism. Unable to return home, she committed herself to publishing poems and novels about racism in America, and soon became a representative of the Maine Anti-Slavery Society and gave numerous anti-slavery lectures that addressed feminism, classism, and racism all across the country. She soon formed alliances with Susan B. Antony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Frederick Douglas; famous figures in the feminist movement at the time. In 1866 she gave a very powerful speech at the National Woman’s Rights Convention where she emphasized the need for equal rights for all, regardless of race. Due to her bold, influential presence concerning equal rights, she became the vice president of the National Association of Colored Women two years later.

Above all, Harper was a brave advocate for women that was not afraid to speak her mind. She believed that Black and white women had to work together in order to achieve their common goal, and even after her death in 1911, Harper’s tremendous efforts towards equality lives on.

Mae Jemison

By Sarah Morrison ‘23

It was the first day of school, 1961. Mae Jemison was only 5 years old, yet a confident and bright kindergartener who could already read. When her teacher asked her, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” Jemison simply responded: “a scientist.” Her teacher seemed surprised—not many women became scientists then, and certainly only a select few Black women. However, in Jemison’s mind, becoming a scientist was the only option and she was determined.

Ultimately, Jemison’s dream became reality when in 1992 she flew into space with six other astronauts aboard the Space Shuttle Endeavour, and became the first Black woman in space. After her groundbreaking flight, Jemison observed that society should understand how many women and individuals in different minority groups will contribute incredibly, if they have the opportunity to do so.

Luckily, Jemison was not only given the opportunity to fly into space. What makes Jemison so astounding is her multitude of accomplishments, lesser known than becoming the first black female astronaut, yet just as remarkable. Mae Jemison is also: a physician, Peace Corps volunteer, teacher, accomplished dancer, founder of two technology companies, and speaks four languages. She attended Stanford University when she was a mere 16 years old, and earned her doctorate in medicine from Cornell University by the age of 25. In 1993, she finally decided to live out her dream and applied to the NASA program, truly inspired by Sally Ride, the first woman in space. Little did young 5-year-old Mae Jemison know that she too would fly into space, among other things of course.

Katherine Dunham

By Isis Ginyard ‘23

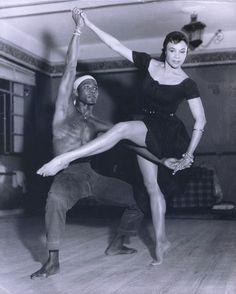

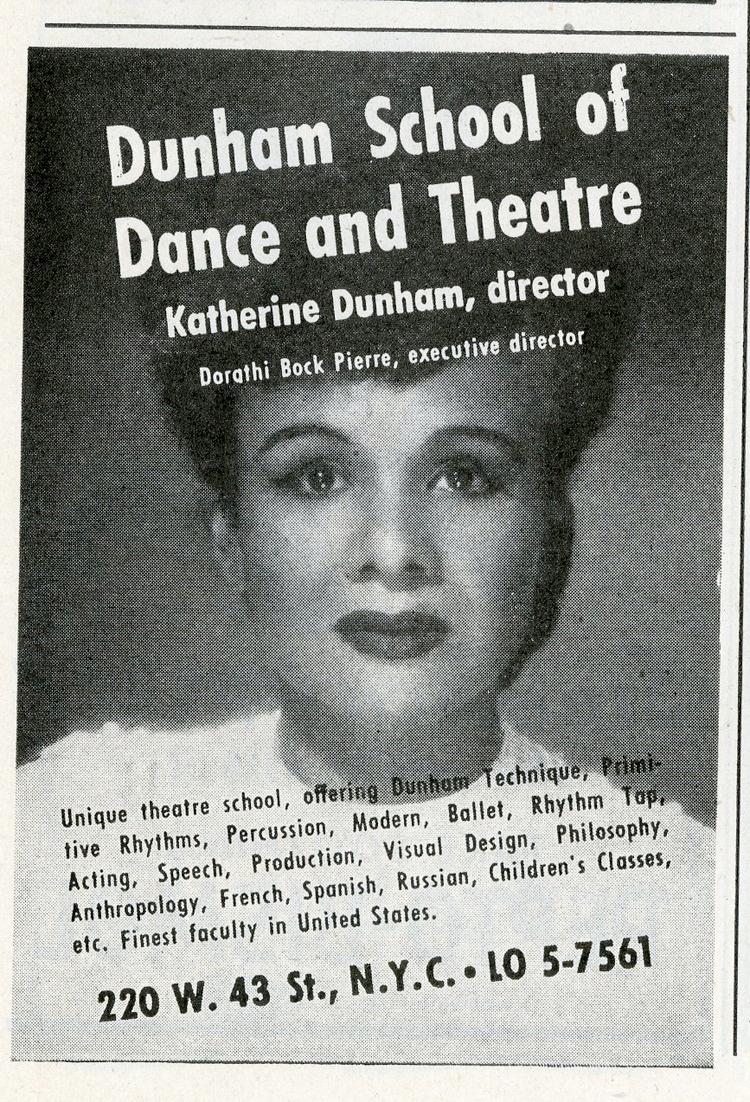

Katherine Dunham was an African American dancer who changed the world of dance forever. She attended the University of Chicago where she started her own dance group which performed at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1934. From 1935-1936 her group also performed with the Chicago Civic Opera Company. She graduated with a bachelor’s degree in anthropology and did field studies in Brazil and the Caribbean. During her time in the Caribbean she studied their culture and its influence on dance. Her work was different from anything anyone had ever seen. It showed people how beautiful African American culture is. She also received her Masters of Arts from the University of Chicago, Dunham learned about tribal dances and rituals which influenced her style of dance. She became a part of the Federal Theatre Project in Chicago in 1938 where she composed the ballet, L’Ag’Ya, inspired by Caribbean dance. In 1939 after moving to New York she performed at the Windsor Theater for a program called Tropics and le Jazz Hot. This was only supposed to be a one night performance, but people loved it so much she ended up doing 13 more weeks.

In 1940, she established one of the first all Black dance groups, which later became the infamous Katherine Dunham Dance Company which focused on African American and Afro- Carribean Dance. Her company toured all around the world, performing in 57 countries in 20 years. Their first performance was in London at the Prince of Wales Theatre in June of 1948 where they performed Caribbean Rhapsody. It was the first time Europe

had truly seen African American culture displayed through art.That same year she performed at the Martin Beck Theater playing Georgia Brown in Cabin in the Sky which she choreographed along with George Balanchie. Dunham has made appearances on the silver screen including films such as Carnival of Rhythm (1942), Stormy Weather (1943), and Casbah (1947).

From 1966-1967, she held the position as artistic and technical director to the President of Senegal. She later became a professor at Southern Illinois University, Edwardsville, and the director of Southern Illinois Performing Arts Training Centre and Dynamic Museum in East St. Louis, Ill. She choreographed pieces for Broadway and Aida (1963) for the New York Metropolitan Opera becoming the first African American to choreograph for the Met. In 1983 she received a Kennedy Center Honor and in 1989 she received a Medal of Arts. Throughout her life she fought against injustice by never performing at segregated venues and raising awareness about injustices in the world through her work.

The Kids that Turned the Tide of Segregation

By Sarah Morrison ‘23

The right to fair education was granted by the United States Supreme Court to students of color in 1954, when it ruled that segregation was unconstitutional. Most of the Civil Right Movement’s emphasis was on education. Education, many thought, would allow minorities to get better jobs in American society and to gain influence. That being said, combating school segregation, especially in the South, meant facing extreme resistance and experiencing brutal violence. So, Central High, in Little Rock, Arkansas became a significant experiment. The Little Rock Nine, a bunch of black students who disputed racial segregation. Consisting of Melba Pattillo, Ernest Gray, Elizabeth Eckford, Minnijean Brown, Terrence Roberts, Carlotta Walls, Jefferson Thomas, Gloria Ray, and Thelma Mothershed, Little Rock Nine thus became the focus of the movement to desegregate public schools in the United States, especially in the South. The events that prompted their enrollment at Little Rock Central High School sparked widespread conversation regarding ethnic separation and civil rights. While they were cautious about integrating a previously white-only college, the nine students enrolled at Central High School on September 4, 1957, were eager for a

meaningful school year. Instead, they were embraced by a furious crowd of white teachers, parents, and people determined to avoid integration. In addition to grappling with racist insults and violent assaults from the mob, Arkansas Governor Orval M. Faubus had gotten involved, directing the Arkansas National Guard to block the nine Black students from attending class. Faced without any other options, Little Rock Nine abandoned their effort to attend classes that morning.

The students, despite every adversity, were determined. The following day, the Little Rock Nine returned to the Central High, however, this time supported by the U.S. Army troops sent by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. For the Little Rock Nine, the fight had only just begun. They endured physical and verbal attacks from white students during the school year, as well as death threats against themselves, their friends, and other Black community members. And one of the nine, Minnijean Brown, was expelled from Central after retaliating against the white students who had assaulted her. Although in May, Ernest Green became the first black student ever to graduate from the Central High. The brave actions of the Little Rock Nine enabled the doors of education for people of color across the nation to open.

Tuskegee Airmen

By Trevor Lamishaw ‘23

As 2020 came to a close, the year of racial injustice and voicing your opinions, it’s important to look back at one of the most influential groups of people that helped pave the way for the Civil Rights Movement. The Tuskegee airmen were the first group of black aviators in the U.S Army Air Corps (AAC), the predecessor to the Air Force. The group of men fought in the second world war, embarked on more than two hundred missions in the three years they fought in the war. In the early twentieth century, the United States Army and the majority of the country had remained segregated in spite of all the black activism fighting for equality. This was especially prevalent in the South, where Jim Crow laws were at their height, along with individual lynching and other attacks from white supremist groups such as the KKK. At the time, only white men were able to serve in any branch of the military, due to the belief that black people were inferior.

In the late 1930s, as Europe was preparing for yet another great war, current President Franklin D. Roosevelt had made the announcement to expand the airforce in preparation for the time when they would be forced to join the war. This expansion however, did not include anyone of a different race. Because of this, Black activist organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and smaller black newspapers like the Chicago Defender and Pittsburgh Courier pushed more fiercely tann previously, in hopes of being heard by the president. Listening to the lobbying and ignoring all the white protests, Roosevelt’s White House announced the expansion of the AAC to black people in September of 1940.

They decided on Tuskegee University in the heart of the Jim Crow run south to be the training facility for the first squadron of black aviators. The location, in Tuskegee, Alabama, had been a final strive to dissuade anyone from coming, in fear that their lives would be in danger. However, a thousand black college graduates and undergraduates from around the nation volunteered to be part of the team. In accompaniment to the thousand aviators, fourteen thousand supporting engineers, flight navigators, and other military civilians came to Tuskegee to be trained in support. The 99th and first black squadron graduated from Tuskegee airbase in 1941.

Led by Lieut. Col. Benjamin O. Davis Jr.—a graduate from West Point, and son of one of the only three other black commanders in the army at the time- the 99th squadron left for Northern Africa in April 1942 which at the time was already controlled by the Allies. The men were given P-40 planes which were significantly slower and harder to control than other planes used at the time, causing Davis to defend his men in front of a War Department Committee for low performance. The men were eventually sent to Italy where they fought among white pilots and shot down 12 German fighter planes in two days, helping to create their reputation.

In 1944, three more all black fighter squadrons from Tuskegee were sent to Europe to fight alongside the 99th squadron creating the 332nd Fighter Group. The group was given P -51 Mustangs to escort heavy bombers within enemy territory. The planes had red stripes on the end of their tails giving them the name the “Red Tails”.

At the end of the war, the Tuskegee Airmen had flown fifteen thousand individual flights, shot down 273 German planes, and one thousand rail cars, while only losing 66 men plus 32 prisoners of war (POW.) The Tuskegee casualty rate was also notably lower than the average death rate in the rest of the 15th Air Force. Though very successful, after the war the Tuskegee airmen returned home to face continued systemic racism. Although today they are not as widely known as they were in the 1940s, at the time they had made incredible leeway into equality for all races in the United States. On July 26, 1948 - three years after the Tuskegee’s last mission - Harry Truman signed Executive Order 9981, desegregating all branches of the United States Military. Many of the original Tuskegee aviators went on to serve long careers in the new Air Force, including Davis, who became the first black general. In 2007, former president George W. Bush acknowledged the bravery of the Tuskegee airmen by honoring the remaining aviators with the Congressional Gold Medal. Then in 2008, former president Barack Obama invited the surviving members to his inauguration acknowledging that his “career in public service was made possible by the path heroes like the Tuskegee Airmen trail-blazed”.