For

A DECADE AGO, YOU HELPED make possible one of our most ambitious reserve acquisitions. Steart Marshes in Somerset has given us 10 years of groundbreaking science, knowledge, skills and experience in restoring saltmarsh at scale. The lessons learned are priceless in the work towards our goal of restoring 20,000 hectares of wetland by 2030. This issue, we celebrate saltmarsh and this dynamic reserve. Big wetlands provide resilience against climate breakdown, but we also need lots of small ones – notably sustainable drainage systems (SuDS). These are places in towns and cities that retain water when it rains rather than letting it pour away into our sewage system and watercourses, sometimes with catastrophic results downstream. And these can be places of wildlife wonder. Read about one of our SuDS for schools initiatives as part of our Bridgwater Blue Heritage Project. It has stepping stones so that kids can enjoy it, rather than being fenced out from an area that would most likely become a rubbish dump. It’s a great example of a SuDS blue space that boosts wildlife and people’s wellbeing, and prevents flooding and sewage pollution – nature is amazing! We need thousands more projects like it.

The magazine of WWT

For WWT

Managing editors: Sophie Bursztyn and Emma Faure, waterlife@wwt.org.uk

Editorial board: Tomos Avent, Jon Boardman, Helen Deavin, Andrew Foot, Geoff Hilton, Peter Lee, Elliot Cassley, Chris Harris

Simon Barnes, Amy-Jane

Paul Bloomfield, Dominic Couzens, Barney Jeffries, Derek Niemann and Mike Unwin

Front cover: Common Pochard Nigel Pye / Alamy Stock Photo

Over the coming months, WWT sites such as Steart Marshes will become havens for migrant birds – all feeding and roosting in huge numbers – and we’re adjusting water levels and managing vegetation to welcome them after their travels. It’s a great time to visit one of our 10 wetland sites to experience the changing of the season.

We’re pressing the new Government to recognise wetlands as crucial to tackling the climate and biodiversity crises, and asking them to support collaboration by helping bring us together with farmers, industry and communities to drive new initiatives forward. You’re helping us achieve great things! Thank you.

Sarah Fowler, Chief Executive

Labour’s landslide victory marks a new chapter for the UK.

WWT is urging this new Government to put people and wildlife first by protecting and restoring wetlands and unlocking the incredible powers that they contain, from preventing floods to cleaning water and improving biodiversity. With the climate and biodiversity crises upon us, we need bold action. WWT wants the new Government to follow up on Labour’s promise to revive nature-rich areas and commit

to restoring 100,000 hectares of wetlands across the UK. This will help ensure economic security, enhance climate resilience and also revive communities. For more details of the policies that can help us achieve this target, read our route maps to a Blue Recovery by scanning the QR code below. We need a national Wetlands Strategy, too, as recommended by the Convention on Wetlands. This would ensure a unified effort across the country to protect, restore and manage wetlands. While many countries have done so, the UK is yet to follow suit, despite being a contracting party of the Convention. We look forward to working with the new Government to help nature burst back to life. We are especially excited to engage with the MPs representing areas around WWT sites, including the four new MPs in the constituencies containing Caerlaverock, Welney, Slimbridge and Steart Marshes. Together, we can restore wetlands like our lives depend on it – because they do.

WWT supporters were out in force for the Restore Nature Now demo on Saturday 22 June. Tens of thousands of people took to the streets of London to stand up and speak up for nature. We were one of more than 400 organisations taking part, and it was wonderful to have so many

of our staff, volunteers and supporters raising their voices for wetlands. Our colleagues from Madagascar carried our banner declaring that ‘the time for wetlands is now’ from Park Lane to Parliament Square. Our walking reedbed also caused quite a stir on the Tube!

A common sight in the UK until the 17th century, spoonbills are now returning. Increasingly breeding here in summer, in winter they can be seen on the south and southwest coasts – look for them at Steart, Slimbridge and Llanelli. Watch as they swish their slightly open, spoon-shaped bills to and fro through shallow, sometimes brackish water in search of dinner.

We’re delighted to announce that WWT Slimbridge has won Gold in the VisitEngland Awards for Excellence 2024 as Large Visitor Attraction of the Year

This prestigious award celebrates the best in tourism, recognising our commitment to quality, innovation and exceptional customer service.

Sarus cranes hold a conference as a vast flock of garganey ducks fills the sky behind them. This spectacular photo was taken by Chhoeurn Socheat, a wildlife ranger in the Boeung Prek Lapouv Protected Landscape in the Lower Mekong Delta, Cambodia, where we’ve been working to restore flooded grassland habitats.

In the background, you can see a dyke built by WWT to hold water at the end of the rainy season. This supports wetland plants such as water chestnuts – a favourite food

of the threatened sarus crane, the world’s tallest flying bird.

Chhoeurn’s photo was the Facebook Favourite winner in the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) 2024 Photo and Video Contest, chosen out of 143 entries from projects supported by CEPF.

“Cambodia’s remaining wetlands support a wealth of wildlife and provide food, water and livelihoods to local people,” says Tomos Avent, Head of International Programmes at WWT. “With vital support from

CEPF, we’re working with the local communities to restore 200 hectares of degraded wetland, prevent the loss of crane habitats, and improve the suitability of the feeding and roosting grounds so these iconic species don’t disappear forever.”

Cambodia’s remaining wetlands support a wealth of wildlife.

Attending the national ceremony as the only finalist from the South West, we are proud to have previously won Bronze for Accessible and Inclusive Tourism in 2023, and now Gold in both the regional and national awards in 2024. With beautiful birds, exciting activities and serene spaces, WWT Slimbridge offers a memorable experience for all.

We’re thrilled to welcome two new WWT Ambassadors to our flock – musician David Gray and award-winning author and naturalist Dara McAnulty.

David, whose album White Ladder is one of the best-selling albums of the 21st century, has long supported wetlands and wildlife.

“I am excited by WWT’s ambition to create 100,000 more hectares of wetlands over the coming years,” he says. “Selling the wonders of vast, untamed expanses of mud and water is perhaps not the easiest job, but it’s a challenge that I’m more than happy to accept.”

At 20 years old, Dara is the youngest-ever winner of the Wainwright Prize for nature writing. He says: “I believe that storytelling is vital in conservation; I look forward to supporting the work of WWT in imaginative ways.

I’m thoroughly delighted!”

See page 28 for our Q&A with David Gray.

WWT Ambassador Dara McAnulty

Join our Zoom AGM

Our 77th AGM will take place on 21 November 2024 from 6pm to 8pm. As more members are now attending our AGM, we will run this year’s event virtually on Zoom. As well as keeping costs down, this will enable more people from across the country to join.

Your membership supports vital work here at WWT, and we’re looking forward to sharing some of this with you. We’ll take stock of successes in saving species and restoring wetland habitats, as well as looking ahead to future plans and challenges. It’s also your chance to share your views and questions with the WWT Council, Board of Trustees, our Chief Executive Sarah Fowler and other members of the team.

To sign up for your free online ticket, visit Eventbrite and search ‘WWT AGM 2024’. Or email events@wwt.org.uk and we’ll send you a link.

A new generation of environmentalists finds inspiration

Three threatened bird species have been given a head start in 2024 through WWT conservation projects

35,000

the

children listened to Ava’s magical story, helping them feel part of the natural world

As part of our ongoing quest for sustainability, we’ve decided to move Waterlife to two seasonal editions. Members will receive one issue covering spring/ summer and another covering autumn/winter. This decision was made in light of our desire to be a sustainable organisation that leads the way in its response to the increasing pressures on the natural world. We want to spend our time and resources communicating with you in the most effective way. If you haven’t already signed up to receive WWT emails, scan the QR code (right) or visit wwt.org.uk/staytuned to receive our latest news.

Children around the UK have been connecting with nature by completing more than 100,000 activities in their school grounds, gardens and local nature spaces as part of our Generation Wild project. Aimed at kids who traditionally don’t get many opportunities to interact directly with the natural world, our awardwinning project has inspired children to complete activities such as building a bird nest, making a bug hotel and gazing at stars in the night sky.

The magical character of Ava – half-girl, halfbird – shared her story with more than 35,000 children, and almost 6,000 have been

inspired to complete 10 or more activities and become Guardians of the Wild, making an oath of allegiance to the natural world. We’ve had amazing feedback from kids, parents and teachers – and now an independent study has confirmed the benefits. Our research with Cardiff University found that children and teachers who took part in the programme felt more connected with nature afterwards, and that their mental wellbeing improved, too.

“ Our award-winning project has inspired children.

On Dartmoor, we raised more than 20 curlew chicks from eggs collected from airfields, where they’d have been destroyed, before releasing them into the wild. We’re hoping that our headstarted curlews will raise chicks of their own to help rebuild the population. This year, four birds we headstarted (three from Slimbridge in 2019 and one from Dartmoor) nested in the Severn and Avon vale. It’s increasingly hard for curlews to raise chicks. We’ve been monitoring nests to better understand the main causes of breeding failure so we can come up with solutions – such as putting up electric fences around nests to keep predators away. In East Anglia, we’ve launched the world’s first conservation breeding programme for black-tailed godwits – fewer than 50 nesting pairs remain in the UK. We released more than 20 chicks this year at WWT and RSPB sites near our Welney centre in Norfolk, keeping another 20 at our conservation breeding unit in Slimbridge to continue the programme. Also at Welney, we released two dozen young corncrakes from a conservation breeding project as part of a wider programme to reintroduce the birds to the Fens. We estimate that there are 10 breeding pairs, and we recorded fi released at WWT Welney last year that had returned aft overwintering in Africa.

We love to hear your thoughts about wetlands, WWT and Waterlife, and to see your photos, so please write to the address on page two or email them to waterlife@wwt.org.uk

The water filter company joins WWT in the ongoing fight to restore and revive the UK’s wetlands

What do BRITA and reedbeds have in common? Both make great water filters. Through our new partnership, we’ll be working together to safeguard wetlands around the UK. BRITA has donated £10,000 to our Blue Recovery Fund, which finances crucial research and conservation

work, and will be giving a further £50,000 over the next two years.

Rebecca Widdowson, Marketing Director at BRITA, says: “Water is the life source of everything and protecting it for the future is a collective responsibility we’re proud to be a part of.”

Pete Lee, WWT Head of Philanthropy, says: “WWT is delighted to be partnering with BRITA. Their valuable contribution to our Blue Recovery work will help us undertake critical research and work to create and restore wetlands in the UK for the benefit of people and nature.”

Thank you, Ian Pratt, for this magnificent shot of a spectacled eider at WWT Arundel. The brilliant white goggles and orange bill are stunning.

Mindful moment

The

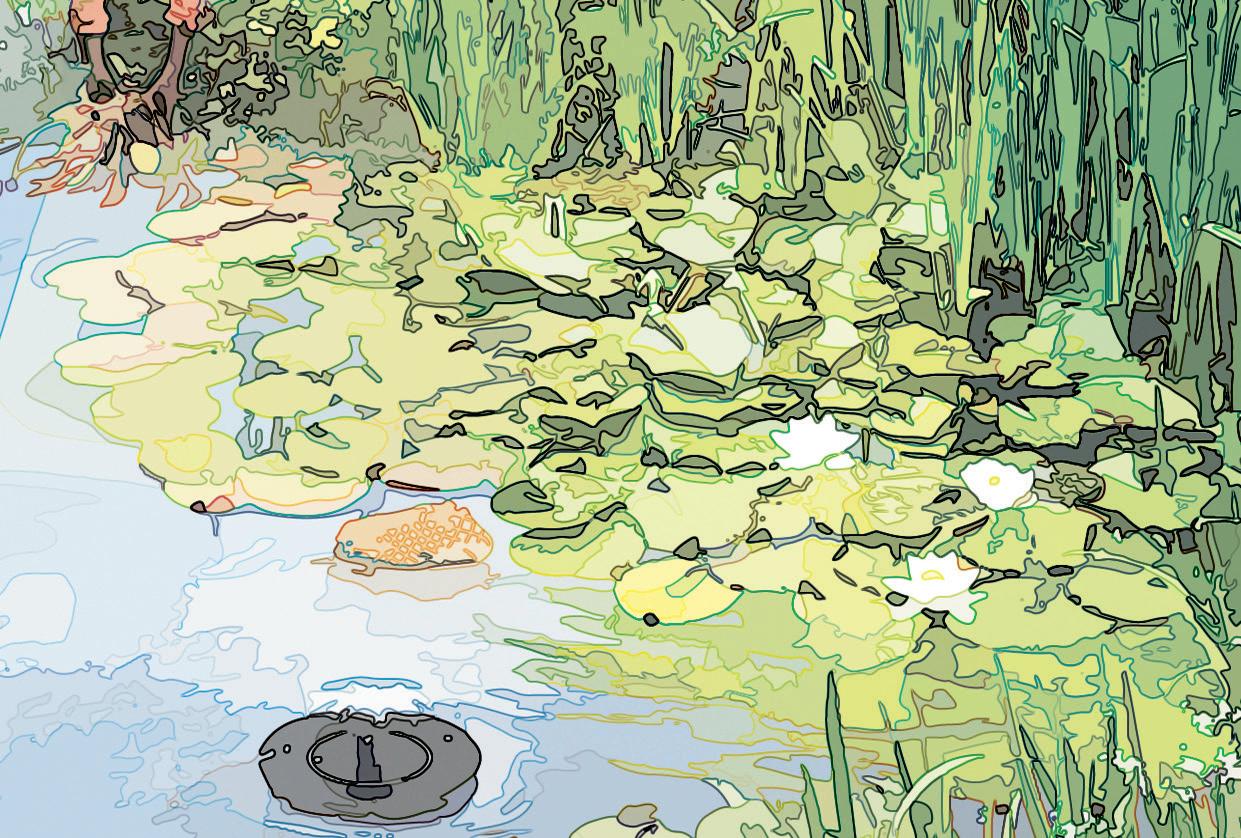

Schools in Somerset are fighting flooding and boosting biodiversity by creating riverbed landscapes to capture rainwater, as part of our Bridgwater Blue Heritage project, funded by the Bridgwater Tidal Barrier scheme. The sustainable drainage systems – or SuDS – are part of an initiative, funded by the Department for Education, that uses wetland solutions ooding and boost climate resilience in one of the UK’s most vulnerable towns. More than 400 planting over 300 plants. As well as providing learning opportunities, SuDS reduce the risk of flooding by holding excess water and provide new habitats for wetland wildlife.

Four-spotted chaser dragonfly

This cranefly image was taken at WWT Llanelli by the outdoor ponds and the Bug Hotel area, which is great for macro photography.

Jonathan Lewis

On a chilly January morning at Slimbridge, I had to wait a while for this egret to venture out into the cold. It was worth the wait.

Win! Win! Win!

Our winner receives a copy of Where to Watch Birds in Britain by Simon Harrap and Nigel Redman (RRP £25). It’s also available to buy at some WWT centre gift shops and online at wwt.org.uk/shop. Funds from every purchase help protect wetland nature.

Please send your best shots of nature and wildlife at our centres to Waterlife and they could be published in a future issue. Just email your high-res images and a short story about what you photographed to waterlife@wwt.org.uk. Show us what you can do!

Seven years after SIMON BARNES visited the then recently created wetlands at Steart Marshes, the author and naturalist returns to see what’s changed – and revels in the volatility of this coastal marsh

Water is a pussycat. Or so we like to think. A bit wild, sure, but at the same time homely. Basically, nice to have around. Sometimes it’s playful and kittenish, in tinkling brooks and tumbling streams; sometimes, in lakes and broad rivers, it’s as majestic as the Egyptian cat-god in a pharaoh’s tomb. But either way, essentially safe.

Wetlands are jumping with the life that comes from water: we see them as benign, generous-hearted places and we’re right to do so. But the pussycat is not the whole story. A trip to Steart

Marshes makes that very clear. Here, the water is sometimes a pride of lions on the rampage, sometimes a tiger lying in wait and sometimes a cheetah moving at unstoppable speed… and then, when you least expect it, it’s just purring on the hearthrug.

Water in its fierce moods can change a place forever and do so overnight – and change it all over again the next day or the next year or the next decade. Just 10 years ago, the place I am walking on was a field of oilseed rape. A few years ago it was a saline lagoon. Now, it’s a saltmarsh.

The marshes lie on the Steart Peninsula: a not-quite island that sticks out into the Severn Estuary with the River Parrett on one side: a great watery landscape rich in sky and, during my visit, echoing with skylarks. Though perhaps it’s more accurate to call it a great landy waterscape. It’s not actually water, but not really land either. In many places (and times) it can change in an instant.

“It’s nice not knowing what will happen next,” says Alys Laver, Site Manager of Steart Marshes.

Managing change

The place is now owned by the Environment Agency and managed by WWT. The local landowners were happy to sell because they were afraid: the tigerish rising waters of the Severn Estuary are becoming more ferocious every day with the driving power of the climate crisis behind them.

The wall built to keep out the sea is no longer big enough or strong enough to do the job. It breached for the first time in 1981. Saltwater was soaking into the once-sweet

“ Water in its fiercer moods can change a place forever and do so overnight.

fields and the power of water was changing everything. So WWT took the place on. After all, wet land is what they’re good at.

How do you solve a problem caused by too much water? Add more water, of course. When you’re dealing with a volatile landscape (or waterscape) like Steart, you soon realise that normal, intuitive understanding doesn’t work.

Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more! I was last here seven years ago, and now Alys and I are back at the spot, near where the Parrett meets the Severn Estuary, where the seawall was opened

1927–1950s

Stert Flats, the mudflats to the northwest of the Steart Peninsula, are used as an RAF air gunnery and bombing range.

1981

permanently – and deliberately.

At a stroke, WWT was no longer fighting the implacable forces of water-driven change but – quite literally – going with the flow.

Water works

That was in September 2014. People lined the banks to see the first tidal inundation. They were thrilled by the change – and not a little fearful. They were worried that the inrushing tides would cause flooding further inland: that more water was the last thing anyone needed.

But it hasn’t happened. And that’s not just a relief for the people of Steart Peninsula, it’s a fascinating demonstration of the way water operates in the time of climate emergency – and how best to deal with it. Not by fighting, but with a carefully managed yielding.

A storm causes floods, devastating the towns of Burnham and Highbridge. Damages to sea defences between Clevedon and Porlock total £6 million.

2009-2011

The Environment Agency and WWT propose to turn the Steart Peninsula into a working wetland, one of the largest in the UK and Europe.

The reserve has expanded massively since my last visit: Bridgwater Bay has been added on and that brings 2,600 hectares to the original 488. Most of the new stuff is mudflat, where all the management is done by the water itself: the twice daily tides. The rich sediment, filled with invertebrate life, is a vast larder for ducks and waders, and on good days you can even see dolphins and porpoises in the river.

And there is the new seawall, a kilometre back from the old one and a good metre and half taller, a lofty bank. “Basically, a five-kilometre-long hay meadow,” Alys says. The skylarks sing on to make sure I understand.

19,000

tonnes of organic carbon were buried in the first four years after WWT Steart Marshes’ creation

The area between the two walls is rich with saltmarsh: a community of specialist plants that supports a busy community of invertebrates.

“This place doesn’t freeze,” Alys says. “So, the invertebrates are active all year round, and that means bats

can feed on them all year. We get 11 different species here, including uncommon species such as lesser and greater horseshoes.”

Changing tides

Saltmarsh is a mysterious habitat, not much studied. “It’s harder to look after than the rest of the reserve because there’s much less data to inform decision-making,” says Alys. Cattle roam the place, now managed in a way that works with wildlife. “This is still a working wetland landscape,” Alys explains. The cows feed on samphire and sea aster, and local farmers sell saltmarsh beef as a premium product. Water floods routinely into this land, but the land

2011-2013

With full community support, works begin. Great crested newts are relocated and water voles head to newly created habitat.

February 2014

The reserve is opened to the public. Volunteers help plant two orchards, which provide a venue for community events and a home for wildlife.

September 2014

The sea wall is breached, allowing tidal seawater to enter the saltmarsh for the first time. WWT manages the new Steart Marshes Reserve.

2015

As the marshes develop, we celebrate our first pair of breeding avocets. They raise the first brood in Somerset in 150 years.

soaks it up like a sponge, at the same time absorbing the constant shock of the wave action. It’s also a great landscape for carbon storage.

We move inland, to areas of saline lagoons, and something that feels more familiar: a place that is more like a well-managed nature reserve, with avocets and the hectic calls of never-calm little ringed plovers. Still further inland the place becomes a freshwater habitat, fed by rain, and there are reedbeds jumping with the song of reed warblers. The place is like a textbook of the different ways water interacts with land. Climate breakdown is not something to do with the future. It’s been happening for 200 years and it’s

“ As I walk the paths, I can feel my understanding of water shifting.

getting faster. And hotter. As a result, the sea is expanding and taking up more room; that’s why sea levels are rising. Hotter air holds more water – 7% for every degree Celsius – so rainfall is getting heavier. The future of our island is about learning to live with more and more water.

Steart is teaching that difficult lesson. As I walk the paths, I can feel my understanding of water shifting. The endlessness of the sky,

the endlessness of the flat landscape and its ever-shifting relationship with the water: rich with the feeling of life responding to constant changes. It’s an edgy place, full of uncertainties. It has changed very much since my last visit; it will have changed again when I make my next.

The wetland way

We humans can fight water for as long and as hard as we like, but the water will have its own way in the end. Here at Steart, the waterscape is being cajoled and persuaded rather than confronted, in the knowledge that in the end it will do what it wants to do.

2019

The first yellow wagtails breed on site and we find sea lavender, a species that doesn’t usually colonise man-made saltmarshes.

July 2019

The freshwater areas are nominated as a Priority Site of National Importance after surveys find 19 species of dragonfly and damselfly.

2020

A pair of black-winged stilts raises three chicks. This is a rare breeding bird in the UK, and the only known pair to have bred in the UK in 2020.

A soft landscape, created by a soft approach to the power of water. A spoonbill, a roe deer, a meadow brown butterfly, a broad-bodied chaser dragonfly; and again and again, a little egret, the signature bird of the place. This species was a wild exoticism half a century back, now it’s a daily delight. We live in changing times, and this lovely white bird, flying across the waterscape trailing its yellow feet, tells us that nothing stays the same and this landscape will change and then change again. wonder what it will be like next time I visit…

2022

Steart Marshes becomes part of England’s largest super National Nature Reserve (sNNR), linking up six existing NNRs and totalling 6,140 hectares.

2023

Simon Barnes is the author of a multitude of wildlife books and articles. He was the chief sports writer for The Times until 2014, has sat on the boards of wide-ranging wildlife charities and was awarded the Rothschild Medal for services to conservation in 2014.

WWT takes over the management of Bridgwater Bay National Nature Reserve, nearly doubling the total area of its land.

2024

An £800,000 grant from the Government’s Species Survival Fund means 370 hectares can be restored across Steart Marshes and Bridgwater Bay.

Our wetlands offer the perfect home to help this lovable species fight back against a serious decline. Here, learn more about them and how to spot one

Words by Derek Niemann

PLANNING, PATIENCE AND SHEER GOOD LUCK may give you a sighting of the impossibly cute hero of Wind in the Willows, a roly-poly, furry, inelegant swimmer, doggy-paddling like a trainee beaver. When Kenneth Grahame wrote about the adventures of Ratty (a water vole despite the name), these rodents were ubiquitous throughout the UK. After the middle of the last century, when there were an estimated eight million, a catastrophic decline saw numbers crash to approximately 130,000.

How did this happen?

Callum Moore, who leads WWT London’s contribution to the London Water Vole Recovery Project, says: “With urbanisation and intensive agriculture over the past few decades, water voles have lost a lot of habitat.” Even worse, the introduction of the invasive American mink decimated their population, which fell by up to 90% from 1989 to 1998.

How do we halt the decline?

Conservation organisations want to create more habitat for water voles, including planting reedbeds. And with mink numbers on the decline, habitat restoration can now really deliver for water voles. WWT’s own target of creating and restoring 100,000 hectares of wetland by 2050 will give a huge boost.

How will water voles spread to places from which they have been lost?

Callum says: “It’s best to let water voles recolonise areas naturally, but where this isn’t possible there will be reintroduction programmes.” The London Water Vole Recovery Project is just one such effort set up to bring back the species to the capital. Today, water voles have a chance to rebuild their numbers across many of our sites. As vegetation dies back, now is the time to look for them. Learn more about water voles at wwt.org.uk/water-vole

Look above the eyes and you simply may not see the tiny ears on a water vole. They’re buried in fur. Rat ears are obvious – pink, hairless and large, they stand up like little saucers.

Water voles are often confused with brown rats (usually someone’s ‘vole’ is actually a rat). However, there are some clear differences between the species that enable you to be sure of your sighting.

Voles are medium to dark brown (black in Scotland), with a darker under belly than rats. Rat upperparts can be light to mid brown, but their bib is always pale grey.

The neat piles of cut vegetation left by voles give a clear indication of the animals’ presence. Rats are opportunistic generalists and leave no such tell-tale signs.

Even a brief view shows a water vole has a blunt-ended or rounded snout. A rat has an obviously pointed muzzle, with more of a V-shaped head.

In the water, the trailing tail is a giveaway.

Voles have hairy, brown tails half the length of their body. A rat tail is as long as its body and head combined, and it is pinkish and hairless.

Feeding

Water voles bite through grass, reeds, sedge stems and twigs as if making an old-fashioned pen nib. They always snip cleanly at a 45-degree angle and, very tidily, leave neat piles of around 10cm cut sections on their pathways. 1

Piles of poo

Vole latrines consist of a close scatter of cylindrical, blunt-ended pellets about 1cm long. The texture of putty when fresh, they may be anything from brown to green and they are odourless. Unlike water vole droppings, rat poo tapers to a point at one or both ends.

Vole holes

If you see a vole squatting on its hind feet, holding and nibbling a stem with its front feet, you’ll notice the furry brown paws. In contrast, rats have

Spot a swimming rodent and its reaction is telling. If it sees you, a rat will keep paddling. The water vole takes evasive action, leaping and diving under the surface with a ‘plop’!

Burrows show as a series of holes along the bank at the water’s edge, just above the water level, each one a little wider than it is high. Others on steep banks may be underwater, serving as boltholes. 3

“For many birdwatchers, winter means vast flocks of geese,” says Kane. “They feed in fields by day and move to open water at dusk, often commuting at dawn and dusk in spectacular V formations. The sight stirs the soul, and they also make a wonderful, laughing call.”

in family parties and older offspring may associate with their parents for some years.

Words by Dominic Couzens

“MANY PEOPLE ARE SAD TO summer end,” says Kane Brides, WWT Senior Research Officer. “But we’re excited by the arrival of autumn and all the birds it brings!” The days are drawing in, greens have turned to gold, but if you think autumn is about winding down, think again. Across all WWT’s reserves, and the country as a whole, life is about to get a whole lot livelier.

Thousands of birds head to our chilly and damp islands in search of refuge from harsher, freezing conditions elsewhere. “Many of our arrivals use the critically important Northwest European

WWT wetlands are about to get noisier and busier as hundreds of thousands of migrant birds arrive on our reserves. After their epic journeys, they’ll be resting, feeding, bickering and pairing up – so get ready to catch the action as these migration superstars put on a show

One of our species is the whitefronted goose, Anser albifrons; albifrons comes from the Latin albus, ‘white’, and frons, ‘forehead’. Some arrive from Russia, spilling over parts of southern England, while another population of larger individuals with more heavily-barred breasts comes from Greenland and mainly winters in Scotland and Ireland. The birds travel

Greenland birds travel first to Iceland and stay for a few weeks before transferring to Britain in late October. With climate change, many fewer Russian birds winter in England than previously because they simply stop in mainland Europe instead.

Slimbridge is one of only three strongholds for the geese in southern England (along with the Thames Estuary and North Warren, Suffolk).

Flyway,” adds Kane. “Birds stream down from the north, east and west, following coasts and wetlands along the route to more temperate climates or Africa. Along the way, these hardy travellers face many challenges – gruelling journeys, uncertain weather, human disturbance and hunting – but thanks to work to protect and conserve their resting and refuelling spots, carried out by WWT and our partners, still they come.” They will stay all winter, bringing drama, vitality and noise to our wetlands. It’s a wonderful spectacle that we can all enjoy. Here, we celebrate some of these new arrivals.

About 300 winter here now, down from the 2,000 or so that were present around 30 years ago.

WHERE TO SEE: Slimbridge

“Many people don’t realise that pochards are migrants,” says Kane. “But there are hardly any pochards here in summer, and then suddenly 48,000 swarm in from northern and eastern Europe, including Russia.” These swift-flying ducks can cover 1,000km in just a couple of days, arriving almost by stealth. The males migrate first and can quickly swamp an area, so the laterarriving females are often compelled to travel further on. A small number migrate as far as west Africa.

WHERE TO SEE:

Martin Mere, Slimbridge,

here later than other migrants, often not in bulk until at least November. “They often arrive in family parties, which might explain why they are pretty noisy!” says Kane.

WHERE TO SEE: Slimbridge, Welney

The red knot has a gift for the spectacular. It’s most famous for its murmuration-like aerobatics when huge numbers gather at an estuary high tide, but its migration is no less astonishing. “In Britain, we don’t get many regular bird migrants from North America,” says Kane. “But if you’re lucky, you may see knots visiting WWT Caerlaverock, or elsewhere on the Solway Firth, from Arctic Canada and Greenland.” The knot finds a migration of 16,000km at great altitude no great challenge. Individuals can cover thousands of kilometres in several days of non-stop flying.

WHERE TO SEE:

With spangled plumage that glows in even the pale winter sun, this highly sociable wader unusually winters on inland fields as well as on estuaries. Most of our wintering birds are from Ireland or are ‘in-house’ migrants that might have bred on Scottish bogs. We also get the Icelandic population either moving through or wintering in the UK. They often accompany lapwings and black-headed gulls as they search for earthworms. Look for the compact flocks that fly high and form crescents, often wheeling around many times before landing.

Brent geese arrive in autumn to visit sheltered estuaries, where they are often remarkably tame. Around 90% of the world’s population of light-bellied birds come to Northern Ireland from Greenland and Arctic Canada, and might have travelled 4,600km to get here, via a stopover in Iceland. Strangford Lough is the single most important site for the population outside the breeding season, and WWT Castle Espie offers front-row views. Their marvellous ‘brr-brr’ call is a constant on many estuaries. They do rather let their kind down when in flight; flying low, they form untidy lines or bunches, when they ought to be making perfect Vs!

WHERE TO SEE: Castle Espie

Most of our wintering black-tailed godwits come here from Iceland, while our breeding birds head to Africa for the winter. These are proper waders, getting their feet wet as they wade in deep water and often immersing their heads when probing in the shallows. Godwits are unusual among waders for being relatively quiet. Think of how much noise oystercatchers or curlews make – there’s a real difference.

WHERE TO SEE: Slimbridge, Steart Marshes, Welney and Martin Mere

This tapered duck is very rare in the summer, but autumn brings an influx of at least 195,000 individuals to all sorts of wetlands, from inland meadows to estuaries. The incredibly smart males lose no time displaying to prospective mates –why wait until spring? These highly sociable ducks are longdistance migrants, and many European birds winter in Africa. WHERE TO SEE: Caerlaverock, Martin Mere and Slimbridge

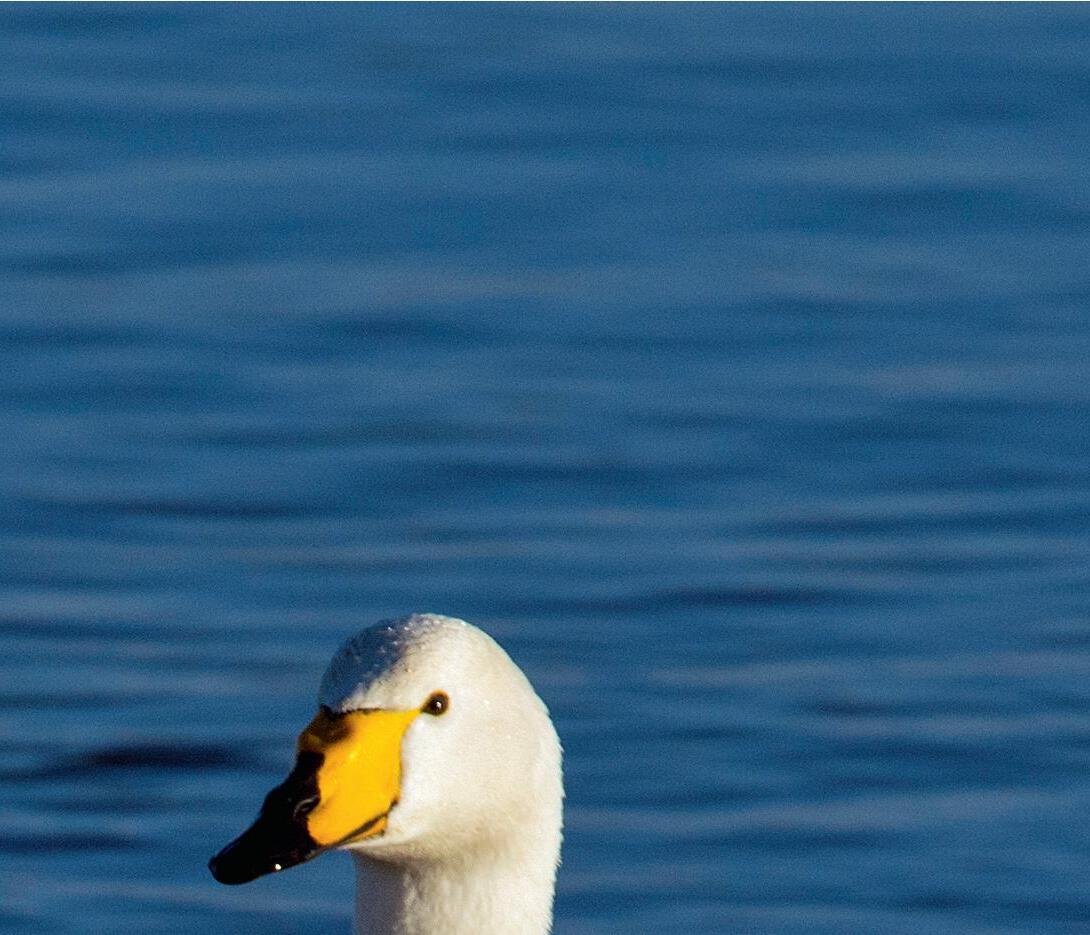

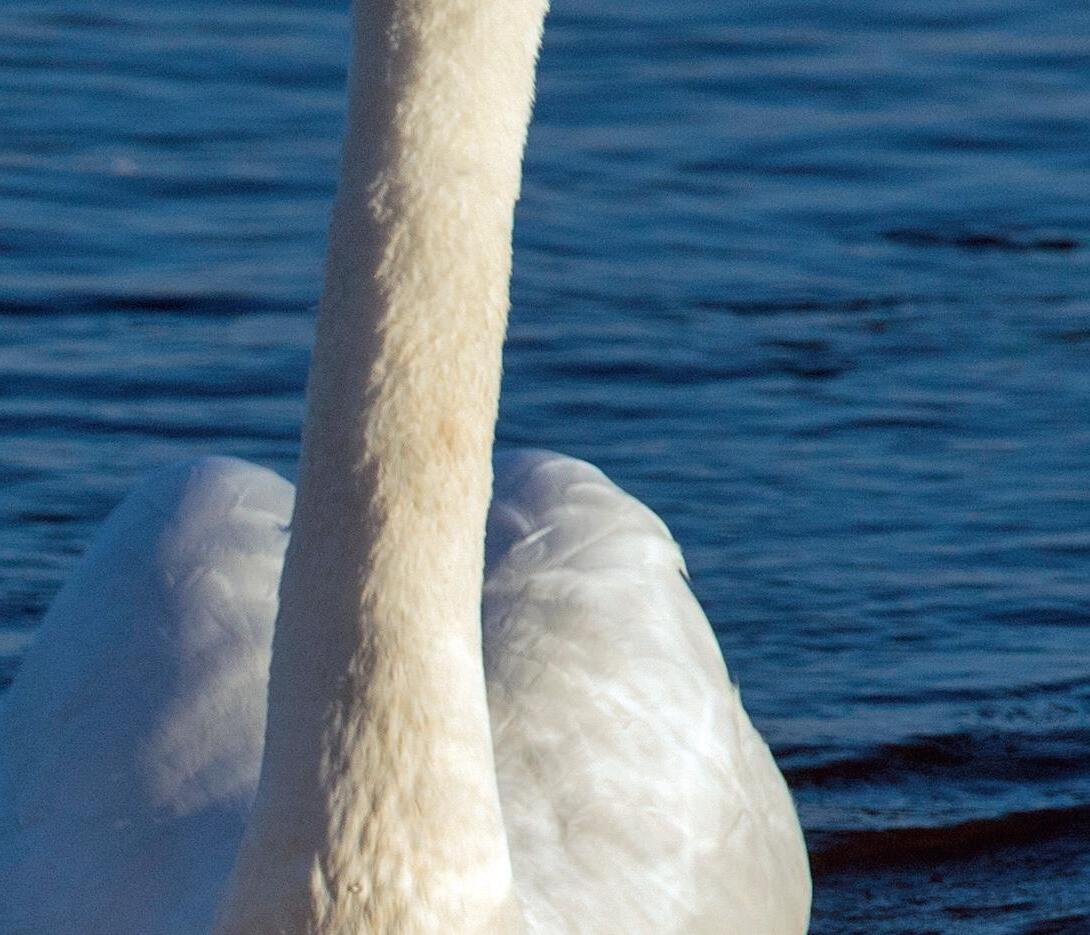

“The whooper swan is our largest migratory bird,” says Kane. “It’s one of the biggest in the world, with a 2.5m wingspan.” Almost all our winter visitors of this species come from Iceland, crossing the 1,000km of North Sea in a single flight that takes about 12 hours flying non-stop. They normally fly a few metres above the sea, but a pilot once recorded whooper swans migrating up at 8,000m, although this is uncommon. They have a trumpeting flight call, unlike the mute swan, which uses the sound of its wings to keep in contact.

WHERE TO SEE: Caerlaverock, Martin Mere and Welney

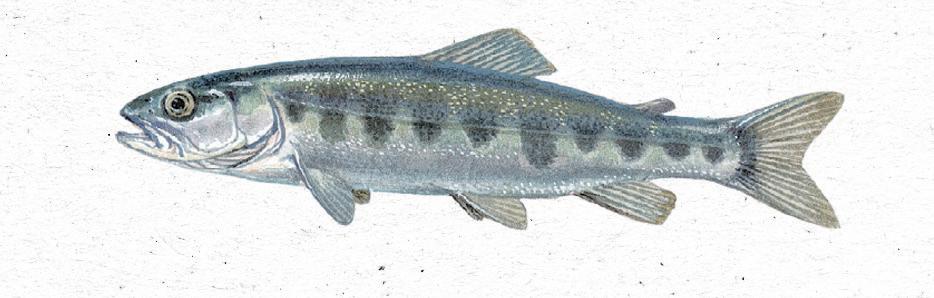

Smaller species and the young of larger species living in our lakes, ponds, rivers and estuaries present a real ID challenge. Our handy guide will help you get to know some of the UK’s most fantastic fish

Words by Derek Niemann

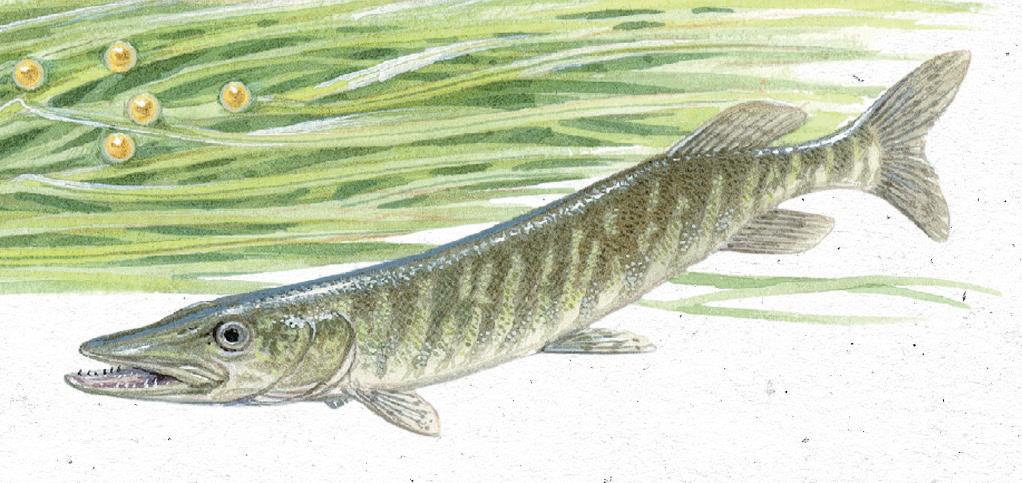

Young pike (known as jacks) have pale bars and spots, plus the classic long, streamlined body and the huge, cavernous mouth of an adult. Pike prefer slow-moving rivers, lakes and ponds, waiting in cover to pounce on all kinds of prey, from other fish to amphibians, young birds and water voles.

Most encounters with salmon are with the immature parr that hatch in freshwater rivers during the spring. They match adults in shape, but they lack a silvery body; instead they have eight to 12 blue-violet fingerprint-shaped marks down their flanks. Voracious hunters, parr are both gregarious and territorial.

Young eels (elvers) lose their glassy transparency in the summer when they acquire yellow-brown pigmentation. In autumn, mature silver eels begin an astonishing migration of up to 10,000km, sometimes across land, then crossing the Atlantic to spawn in the Sargasso Sea near Bermuda.

Noemacheilus barbatulus

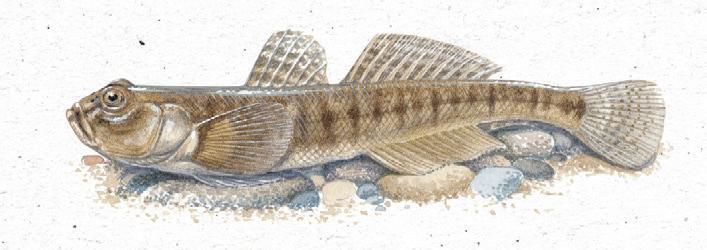

Hiding by day among small rocks in stony rivers or lakesides, stone loaches come out at night to feed on bottomfeeding crustaceans and worms. Six barbels around the mouth are a defining feature, while a mottled green-yellow body provides excellent camouflage.

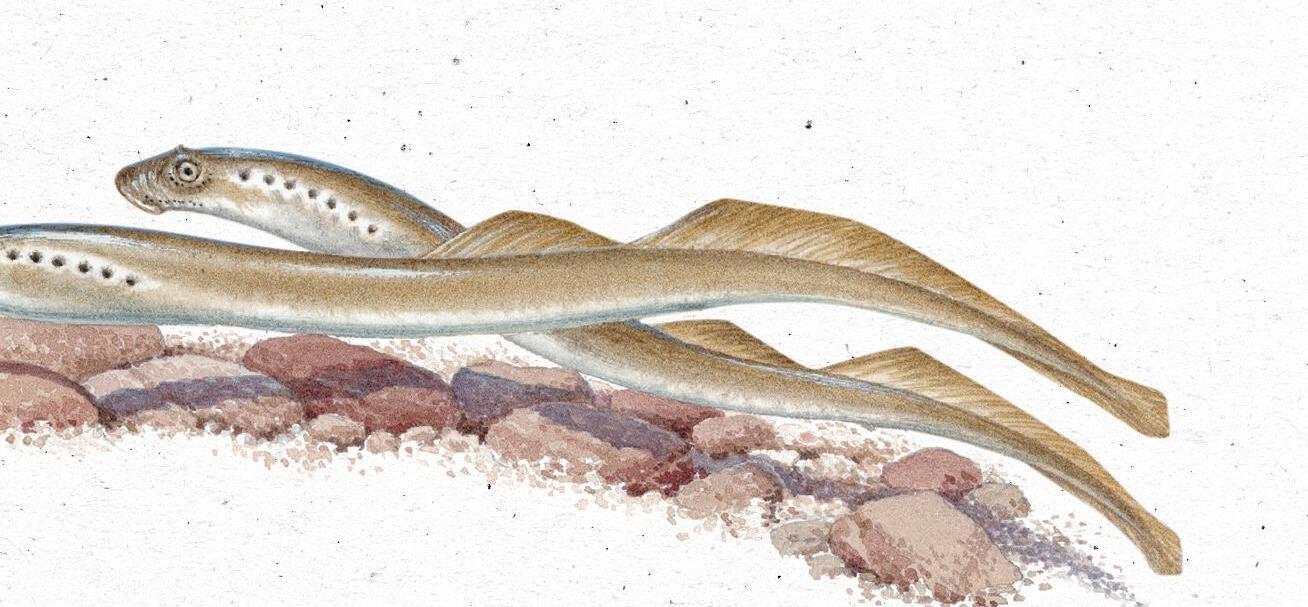

This stream-dwelling fish is easily confused with a young eel or a river lamprey, a closely related species. It spends up to five years as a worm-like larva living in mud before becoming an adult in the autumn. Though the adult has a jawless sucker mouth, it never feeds, and dies after spawning in spring.

This gregarious goby is fond of tidal rock pools around the coast, where it swims in shoals close to the bottom, feeding on tiny crustaceans. Its fawn and grey back with dots and pale patches offers camouflage against a sandy substrate. It enters estuaries from April to September and often swims upstream into the freshwater zone.

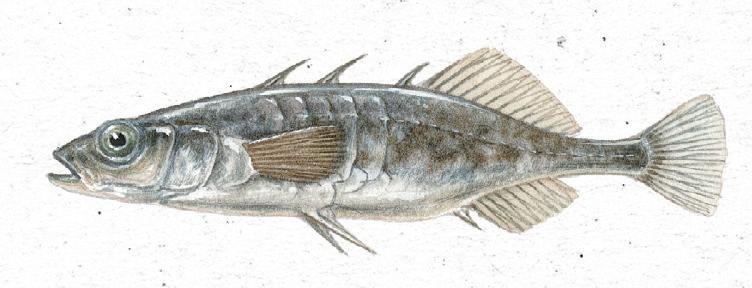

The commonest member of the UK’s smallest freshwater fish family, the three-spined stickleback is distinguished by the three spines on its back. It lives in all habitats, from ponds to estuaries, although it prefers slow-moving or still water where hundreds of juveniles shoal.

A 5cm-long tiddler found in the margins of larger lakes and rivers, the minnow has such fine skin and tiny scales that it appears to be scaleless. The omnivorous juveniles shoal with other species, hunting out small invertebrates and algae. Breeding males

One of the UK’s most widespread fish, the roach is slow-growing, reaching 10-40cm with a lifespan of eight to 14 years. Adults have a silvery body and bright-red fins. The juveniles are omnivorous, feeding on both small invertebrates and algae.

An exceptionally broad head gives this fish both of its names. It lurks under stones on the bed of a clean river or lakeside, coming out at night to feed on insects and crustaceans. Spines on its head and fins offer a prickly defence

As we welcome the influential singer-songwriter to his new role as a WWT Ambassador, DAVID GRAY talks exclusively to Amy-Jane Beer about his career, creativity and love of the natural world

Words: Amy-Jane Beer

You’re not long back from a global tour marking the 20th anniversary of your acclaimed album White Ladder. What brings you from the concert arena to our wetlands?

They’re linked. Touring has an environmental footprint and I wanted to compensate in a way that was meaningful to me. I was wary of commercial carbon-offsetting schemes because the climate crisis is only part of the emergency we face and, for me, compensation needs to be more intelligent than just handing over money.

I’d heard about WWT’s blue carbon ideas, which married climate wins with wins for nature. So, I got in touch

“As a child I was fascinated by every living thing, from slow worms to buzzards.

and was taken on a tour of WWT Welney in Norfolk and Steart Marshes in Somerset. I saw first hand how reclaiming saltmarsh was not only great for wildlife and carbon storage, but also brought other gains such as water filtration and flood mitigation. I was very impressed.

WWT is a prestigious and science-led charity with an amazing heritage that also embraces community and culture. That’s important because changes in land use affect communities, and when it comes to conservation and the environment, people are often overlooked. I took the tour of the sites and the relationship with WWT has grown from there.

Where did your love of the natural world begin?

As a child I was fascinated not just by dinosaurs, but by every living thing, from slow worms to snails and buzzards. When I was very young, we moved from Manchester to Solva, a beautiful fishing village in Pembrokeshire. My time there was a constant voyage of discovery, always outdoors, not even looking for things, just finding them.

When I was seven, our neighbour Buzz Bland, a fisherman, offered to take me out for the day trawling and collecting lobster pots. We sailed nine miles over the sea to Skomer – a place I’d seen on the horizon, but only ever imagined visiting. We ate mackerel

straight out of the sea for breakfast and, as we approached the island, I saw shearwaters, puffins, guillemots, razorbills and storm petrels skittering across the water like little sparrows. The closer we got, the more birds there were – the noise was incredible!

Is that when nature began to seep into your work?

I’ll never forget the sense of scale and life all around me. My shallow view of nature was replaced with awareness of something grand and infinite. My passion grew throughout that time, but it went to sleep as I became a teenager and got interested in other things. But in my mid 30s, having had some success with my music, I took a breath. I bought a cottage in Norfolk and a new chapter began.

It flooded in! I live right by the marsh and the dunes, where magic happens – things you’d never expect, even if you take the same circuit every time (which I do). It’s endlessly renewing and affords me a perspective that’s like getting rid of the self and dissolving

you’re part of everything – the speaking world, I call it. I’ve always written about the human heart, the mystery of being, but nature infiltrates my work more and more.

You’re a passionate advocate for curlews. How did that happen?

I first remember seeing curlews on the west coast of Scotland where my dad

You obviously feel the nature crisis very deeply?

fond of them. However, didn’t actually understand their plight. In fact, when

idea that the birds I saw there were overwintering. I just thought, “Wow, 200 curlews, they’re doing well.” But after reading Mary Colwell’s book, Curlew Moon the seismic realisation hit me that these stately and mysterious birds that I loved really were in dire straits. I try to imagine the landscape without them, as is happening right now with turtle doves, cuckoos and nightingales. It seems unthinkable, but it’s happening.

I have a sense of ecological panic. It’s not always front and centre of my mind, but it’s always there; the awareness of jeopardy, like a wrong note, a discordant drone just behind the melody.

How do you deal with that anxiety day to day?

81%

of participants on a study of outdoor swimming found they felt “recovered”*

sing. How song can be so much more resonant than conversation, so potent in accessing feelings and memories, simultaneously rich and powerful, nude and humble. Music brings us in contact with the strange substance of time, and the fleeting beauty of being alive. What I hear in birdsong is an utterly unselfconscious version of that.

How can the arts, particularly music, help with nature recovery? Art is a way to bring people in. Nature reserves can help people reattune to the natural world, but art can help us understand our place within it. Storytelling is key to communication, and poetry and music bring a little bit of the outside world in and recharge “ I live right by the marsh and the dunes, where magic happens.

Sea swimming helps me to deal with it. I go swimming every morning and evening from April to the end of October. Something happens to you after the first 90 seconds of cold shock – it’s something like an ecstatic state and it sets you up for the rest of the day.

Does the plight of birds celebrated for their voice resonate with you as a singer?

I’m fascinated by what happens in our heart, body and mind when we

Nature and climate crises are emergencies. We need the people at the top to act.

us in a new way. I’m very prepared to use my art as part of my conservation work, and I’d like to see WWT expand on that, too.

How can you use your platform to influence others?

I’d like to help educate the music industry. Not just musicians, the whole game – record companies, ticketing businesses, venues, fans. Climate is starting to get attention from the industry, but we need the same for nature, and it should be an easier sell especially since the pandemic. Everybody seems to have a nature story and that’s what I want to tap into. We can all become lobbyists if

look. Start with the basics: the air; the water; the soil; the insects. We need a serious conversation about agriculture and we’ve got to bring communities on board. I’m not underestimating how hard that might be, but look what happened during the pandemic: stuff happened that would have been unacceptable under any other circumstances because there was an emergency. Nature and climate crises are also emergencies, so we need the people at the top to act.

And what about the rest of us?

Reconnection. We’re so easily distracted. For generations there’s been one technological bomb after another and a narcissistic culture has exploded into hyper-narcissism. We should be turning off our phones and stepping outside. We all need to reconnect with nature – it should be compulsory for people in power. Until politicians see nature as a vote winner, private commitments by individuals and organisations really matter. The scale of wetland restoration WWT hopes to achieve will require huge amounts of money, expertise and organisation, but there are so many things that can happen at a local community scale. We all need to start focusing on what’s in front of us. We shouldn’t be relying on charitable means as the sole answer – it doesn’t matter if you have 50p or £50 million to give, you can help a bumblebee or an entire ecosystem. We should all be doing it.

Finally, what’s your best bit of kit?

we educate ourselves. You have to make an informed plea and not just sound like some bleeding heart.

What would you say to our new Prime Minister to convince him to act for nature?

Whether you’re Prime Minister, the head of Amazon UK or just you or me, you’ve got to take a long hard

My binoculars. You can see a bird with your eyes 40 yards away, but only with binoculars can you see its expression, what it’s doing and the interactions between individuals. You enter their world and everything else dissolves.

David’s song for the curlew The Arc is available on his album Simmerdim: Curlew Sounds. His new album will be released in January. davidgray.com

Wetlands are full of life and inspiration. As our annual members’ photo competition returns, we can’t wait to share your most special wildlife sightings from the past year

IN THE QUIETEST CORNERS OF your local WWT site, a regular group of visitors can often be found. They are the wildlife photographers, the silent observers of nature’s beauty and her mysteries and, thanks to them, we can all marvel at our amazing wetland wildlife any time.

A photographer’s time is spent not just looking, but observing, learning and connecting with nature. Their aim is to get under the skin of a wild place and discover the secret wildlife others may miss, from a diving otter to a hunting marsh harrier or an egg-laying emperor dragonfly. They are masters of interpreting body language, reading the subtle signs that a grebe is about to dive or a grey heron to stab at a fish. These are the hidden gems they share with us every year thanks to our photo competition, and we’re so grateful. Richard Allan is a photographer and WWT member who has been a

finalist in our competition many times. So, this year, we invited him to share his unique insights and top tips for photographing wildlife at a WWT site. We hope they will inspire you.

The winner of the adult category will be awarded a pair of Viking Osprey 8x42 binoculars. The winner of the youth category (under 16) will receive a pair of Swarovski Optik binoculars. Winning photos will be published in Waterlife and our long list of finalists will also be published on our website at wwt.org.uk/waterlifephoto

Now it’s time to go through your archives and send in your very best shots to this year’s photo competition.

• Images must have been taken at a WWT centre at any time throughout 2024.

• As always, you must be a member to enter (you’ll need your member number ID).

Enter now!

I love visiting WWT Arundel for the year-round wildlife photography opportunities it offers. My focus can change with the seasons, from birds such as snipe and firecrests in autumn and winter to kingfishers and dragonflies in spring and summer. I can challenge myself, hone my skills and develop artistic shots using the Living Collections as subjects. Here are my tips for making the most of your next visit.

1 Spend time getting to know your WWT centre. Talk to staff and other visitors, especially photographers, to increase your knowledge of what you might expect at different times of the year or day.

2 Choose the best time to visit to increase your chances of photographic success. Consider when the light will be at the right angle for your target photo or when there’s likely to be fewer people around, as they may affect shy creatures.

3 Don’t be put off by mesh netting around enclosures. Get close and shoot centrally through a gap using a wide aperture and a long focal length, and you’ll find the mesh often blurs away.

4 Pick a few areas of the reserve to focus on. Spending time waiting to capture behaviour, such as bathing, caring for young or territory defence, is usually far more productive than strolling around hoping to see something.

5 Look for other wetland wildlife, not just birds. Water voles lend themselves to cute portraits, while insects and wildflowers make interesting, colourful subjects when captured close up.

I love the detail and splashes of colour in close-up shots of butterflies. To avoid disturbing this resting red admiral at WWT Arundel, I used a long 500mm lens with a wide aperture setting to create a shallow depth of field.

For full T&Cs and to enter, visit wwt.org.uk/waterlifephoto

Entries close at midnight on 31 December 2024.

6 Explore the raised man-made ponds when they’re not being used by schools for pond dipping. They attract many types of dragonflies and damselflies, which make beautiful, if challenging, macro subjects. Their raised position also gives you a better chance of capturing an eye-level perspective.

7 When photographing wild animals from a hide, use your camera’s silent mode to avoid scaring the wildlife away and irritating other hide users.

We can’t wait to see our lifegiving wetlands and all their wonderful watery wildlife through your eyes. Good luck!

Big or small, a pond is a haven for wetland wildlife. Find out how to nurture this vital ecosystem and keep it healthy all year

Words by Paul Bloomfield Illustration by Stuart Jackson-Carter

THE LITTLE LAGOON IN YOUR garden

is a thriving nature sanctuary, teeming with life. Ponds support two-thirds of all UK freshwater species, from newts and frogs to dragonfly larvae and water beetles. They provide a nursery for the flying insects, and larger water bodies provide hunting grounds for grass snakes. Yet these important oases have declined, with half of the UK’s ponds lost since the 19th century. And with 83% of freshwater species in decline worldwide, creating and looking after ponds, big or small, is vital for wetland biodiversity.

Our seasonal tips will help you keep your pond in tip-top health for wildlife. That doesn’t mean making dramatic changes – a pond is a dynamic habitat, so avoid over-tidying or disrupting the ecosystem. By spending time with your pond, observing the natural rhythms of its residents, you can work out what needs to be done the most. Enjoy the fruits of your labour. Look for dragonflies and damselflies, and tadpoles metamorphosing into froglets and dispersing into your garden (a good reason not to mow to the water’s edge – leave it long in places to provide cover for these mini-amphibians).

Autumn: clear dead vegetation

As water plants die back, clear dead leaves and stalks, leaving roots intact, but be careful not to remove too much over-wintering habitat. Creatures live on leaves and stems so, before composting, lay them on a tarpaulin or plastic sheet by the edge of your pond for a day or so to allow invertebrates to crawl back to the water. Alternatively, wash plant matter in a bowl of pond water, then return any creatures to the pond.

Autumn: create a thriving amphibitat

Provide a pondside shelter in which amphibians can hibernate. Create a pile of rocks, or logs and sticks, leave some long vegetation and put out an old flowerpot with holes for newts. Leaves can accumulate in your pond. Too much decomposing vegetation can increase nitrogen levels, but leave some in the water: leaf litter, twigs and other vegetation provide food and shelter for invertebrates.

Winter: fight the freeze

Don’t be alarmed if the water freezes over: a healthy pond with underwater plants will stay well oxygenated and life will continue to thrive. But ice does stop birds from reaching the water, so leave a ball floating near the edge to create a hole. Don’t smash the ice or pour on boiling water as this harms pondlife. Brush snow off the ice so sunlight gets in.

Autumn: let sediment lie

A layer of sediment at the bottom of a pond is natural, providing a home for mud-dwelling invertebrates. Avoid removing unless it’s absolutely necessary and take out no more than half of the excess. If you do have to remove sediment – or do any other significant work – leave it until late September or October, after froglets have left and before the adults arrive.

Spring: use a natural remedy

Excessive blanketweed and algae can form mats, blocking sunlight from reaching submerged plants and reducing oxygen levels. One natural way to address this is to place a mesh bag containing barley straw into the pond in spring; as it breaks down, chemicals are released that inhibit algal growth. Remove the straw when it’s turned black a few months later.

Summer: remove any smothering pondweeds

Plants and algae tend to proliferate in summer – that’s normal, and you don’t need to remove them unless your pond is getting really choked up. If necessary, scoop out excess duckweed with a small net and twirl a bamboo cane very gently to pick up blanketweed. As in autumn, wash this in pondwater or leave by the edge to allow invertebrates to return to the water before composting. Invest in a solar-powered bubbler. Leave it in the pond all year to keep the water oxygenated

Spring: watch wildlife arrive

Winter: leave sheltering water plants

Don’t cut back plants at the water’s edge until late winter to allow invertebrates to shelter for as long as possible. If overhanging vegetation drops too many leaves into your pond – or could create too much shade in summer – trim it back now.

Spring is a busy season. Frogspawn laid in January is hatching, while newts and toads are laying eggs, and invertebrates are arriving at ponds. So, while early spring can be a good time to remove excess duckweed and thin out marginal plants (leaving at least three-quarters of them intact), try not to disturb the pond itself.

Pond perfect For our top tips on everything from creating a pond to choosing plants, visit wwt.org.uk/ gardening

Summer: beat the drought If water recedes during dry periods, don’t panic. Freshwater species have evolved to survive in these changing conditions which, in fact, create biologically productive areas of mud. Only when levels sink below about 2-5cm deep, or water heats to around 35°C, should you top up –but never with mains tap water. Use rainwater from a water butt instead.

There’s magic in the air across our sites this autumn, and our wetlands are ready for you to come along and fall under their spell.

This October half term, enjoy a week of supernatural activities. From making spooky animal crafts, potions and willow wands to nature hunts, plus our new Magical Halloween Light Trail at Slimbridge, there’s lots on offer to capture the kids’ imagination.

You don’t need binoculars to experience the wonder of our huge winter flocks. You could see swans feeding and birds roosting together in the evening, all while enjoying the fresh winter air. With unlimited visits with your membership, this is the golden season to see just how super wetland nature can be.

When the sun goes down, a whole new world will light up at WWT Slimbridge. Our new Halloween Light Trail will take you on a journey that’s just as amazing as the wildlife you’ll see during the day. Take an enchanting stroll along a dazzling light trail to discover a shipwreck, a bubbling pond, a narwhal and more. Make lanterns and toast marshmallows, then meet our Mystical Marsh Witch, protector of our magical wetlands, to make a wish. It’s mystical from dawn to dusk!

WHERE: Slimbridge, open until 9pm, entry fee applies. 11-12, 18-19 October, 25 October-3 November

Hop to it!

Friday Froglets

Join our forest school-inspired Friday Froglets sessions with your children. Here, there’s the opportunity to play in nature, learn some new songs and share stories, make nature-inspired crafts and finish your visit with quiet time around a fire! This autumn activity is fantastic fun for children and adults alike.

Catch the evening roost

As the evenings draw in, many birds come together in large numbers to roost for the night – and November is your chance to experience this winter spectacle. Stay late at the centre to see flocks of pied wagtails dropping into the reedbeds, little egrets in the trees around the lagoon and marsh harriers floating over the reeds.

WHERE: Arundel, 6 & 9 November

Unleash your creative spirit and make a unique decoration for your home at one of our crafts workshops

Immortalise your favourite natural marvels in colourful designs with a one-day stained-glass workshop. Learn to craft a beautiful piece of art depicting a subject from the natural world, from delicate insects to stars, or more abstract patterns. All materials and tools are provided – just bring your imagination!

WHERE: London, 16 November

WHERE: London, Fridays, September Nature craft time!

Welcome a beloved bird into your home at a workshop with the Bentley Wildlife Carvers. Starting with a plain block of wood, you’ll sculpt and paint a personalised model of one treasured species to create your very own avian artwork – with plenty of nurturing guidance from the experts, of course.

WHERE: Arundel, 20 October & 24 November

nomads return for the winter in one of our most breathtaking wildlife spectacles! Join us for our Big Brent Welcome Weekend to celebrate the arrival of some 25,000 light-bellied Brent geese at Strangford Lough after a 3,000-mile odyssey from Arctic Canada. Learn all about this amazing mass migration at the family fun-packed weekend, which includes photography sessions and children’s crafts workshops.

WHERE: Castle Espie, 5-6 October

Hear from famous nature lovers and TV stars including Nick Baker, Gillian Burke (right) and George McGavin at the North West Bird Watching Festival – the region’s top birding event. Thrill to the sight of thousands of pink-footed geese taking flight at dawn or returning to their roost at dusk. Add photography workshops, exhibits, guided walks and boat tours for a sensational weekend.

For more details of wildlife experiences, go to wwt.org.uk/ visit

WHERE: Martin Mere, 19-20 October

Be inspired by the amazing journey of barnacle and pink-footed geese from the Arctic during our annual Wild Goose Festival. Get involved with activities including family-friendly storytelling and nature walks, plus whisky-tasting, ‘goose breakfasts’ at a nearby café –and the chance to see these long-distance travellers flap off to feed at sunrise and return to the mudflats as the sun dips.

WHERE: Caerlaverock, 19–27 October

Come autumn, a dazzling variety of birds feast on Llanelli’s wetland bounty – some of them residents, many others dropping in to refuel on their epic migrations to warmer climes for winter. And as super-high seasonal tides usher them closer to our hides, this is a fabulous time to get up-close and personal with views of elegant and entertaining wading birds such as little egrets, greenshanks and black-tailed godwits, plus colourful, charismatic ducks including teals, wigeons and shovelers. Book your table for our special after-hours High Tide and High Tea event to enjoy a delicious sunset feast while absorbing an avian extravaganza. WHERE: Llanelli, check website for the latest details

a

Visit your nearest site to see wetland wildlife spectacles and deepen your connection with nature. Here’s our pick of this season’s favourites

1. Return of the Brent CASTLE ESPIE

The return of our Brent geese is a thrilling sight – about 25,000 fly from Arctic Canada to Strangford Lough.

2. Go wild for whoopers CAERLAVEROCK

Whooper swans fly from Iceland to spend the winter with us. Daily commentated feeds allow you to see these striking birds up close.

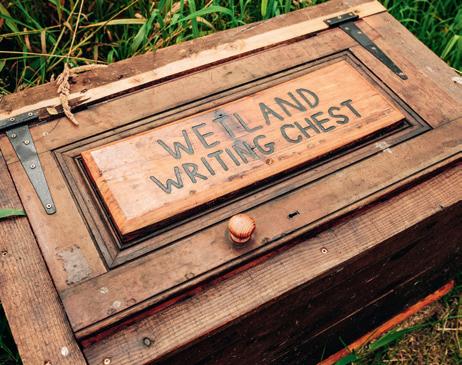

Feeling inspired by our entrancing blue spaces and the glorious wildlife they nurture? Seek out the Wetland Writing Chest, a beautiful wooden treasure trove crafted largely with recycled materials rescued from around the reserve. Take your pencil and jot down your poems or musings in the Caerlaverock Journal nestling in the chest. This ever-growing compendium of nature writing is an enriching way to record experiences, embed unique memories and connect with wetlands and the wider environment. WHERE: Caerlaverock, this autumn and winter

3. Curlew crazy WASHINGTON

Our winter curlew roost is at its best from November to January, with numbers swelling to more than 900 as the weather turns.

4. Autumn’s migrants LLANELLI

Thousands of migratory ducks and waders stop at Llanelli in autumn. Enjoy close-up views of their dazzling colours as they rest and refuel.

5. Crane spotting WELNEY

Arctic arrivals including pochard plus Bewick’s and whooper swans join local flocks of cranes and resident barn owls.

6. Our Bewick’s are back!

SLIMBRIDGE

From November, Bewick’s swans arrive from Arctic Russia, often with cygnets. The daily rollcall on our website welcomes back known individuals.

7. Top spots

LONDON

Watch the arrival of rare migratory birds such as green sandpipers and black-tailed godwits against a backdrop of autumn leaves.

8. Magical marsh harriers

ARUNDEL

Up to 10 marsh harriers roost in our reedbeds from late October to February. See them soar over the beds from the Scrape hide or long path.

10.

STEART

All sorts of walks are available, including a history of the site, birdwatching dusk/night walks and 4x4 tours.

action we can manage our own anxiety, make a positive impact (even if it is small to begin with) and, most importantly, lay claim to a right to care. Thus, we become a potent force for that change.

“ What if it takes a community to look after a special place?

Dr Amy-Jane Beer celebrates the power of the individual to drive change

While many of the grassroots campaigns enacting guardianship of rivers, lakes and peat bogs now involve several people, most started with individuals acting alone. With that in mind, I ask you to consider where is your nearest wetland? Not your nearest wetland reserve, or country park, but the actual nearest? How well do you know it? Where does its water come from and where does it go? Who is supposed to take care of it and are they doing a good job? If not, there may be an unhappy reason that has more to do with a landowner not coping than with exploitation or neglect, but either way action might be needed. There’s a saying that it takes a village to raise a child. What if it also takes a community to look after a special place? Because even if a landowner is doing everything right, fortunes change, and their tenure is as fleeting as any human life. There is resilience, as well as strength, in community.

I’m encouraged by the new Labour Government’s manifesto pledges around community right to buy, and in particular the potential for natural entities such as riversides and woodlands to be registered as Assets of Community Value. This is a prerequisite to that right, which has previously applied to assets such as village shops and pubs. But what if it included ponds, riverbanks or peat bogs, the value of which might be flood mitigation, carbon storage, water purification, or the health benefits of blue-green space for nature restoration and recreation?

Dr Amy-Jane Beer

is a biologist, writer, editor, outdoor enthusiast and mum from North Yorkshire

CHATTING TO MUSICIAN AND WWT

Ambassador David Gray for the interview on page 28, was struck by his belief in community and in taking whatever action for nature your personal capacity allows – be that helping a hedgehog or an entire ecosystem. He’s right. We can all plug a gap, be it large or small – just pick one you can manage. This isn’t some ‘big society’-style buck-pass attempt to deflect from the need for systemic change, but a recognition that in taking

With a slight proviso that such a scheme should be drafted carefully to avoid empowering affluent ‘nimbys’ to stymie developments for which there is a great social need, this is potentially powerful legislation. The new administration should be pushed hard to deliver on it.

Listen to our podcast If you love nature like Amy, immerse yourself in Waterlands, our wetland nature podcast. Scan the QR code or visit: wwt.org.uk/waterlands

Membership

Gift unlimited visits to our 10 wetlands sites around the UK for only £2.50 per month.