38 minute read

Jules Olitski Chronology Alex Grimley

from Jules Olitski

by Yares Art

JULES OLITSKI CHRONOLOGY

by Alex Grimley

Advertisement

Fig. 1 Jules Olitski with sculpted figure, ca. 1940s.

Fig.2 Jules Olitski. Woman with Purple Hand, 1950. Oil on paper mounted on board, 41 ¼ x 27 ¾ in. (104.8 x 60.3 cm). Private Collection. 1922–1939 On March 27, 1922, Jules Olitski is born Jevel Demikovsky in Snovsk, Soviet Russia, the only child of Jevel and Anna Demikovsky (née Zarnitskya).1 His father, a Soviet commissar, is accused of theft, brought to trial, and executed by the Soviet government in December 1921, shortly before Olitski’s birth. Following a brief stop in Gomel, Anna, her mother Freida, and the infant Jevel emigrate to the United States, settling first in Jamaica, Queens, then in Brooklyn. In 1926, Anna marries Hyman Olitsky, a widower with two sons. At age seventeen, Olitski sees paintings by Rembrandt for the first time at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. His nascent interest in art becomes an overriding passion. He draws at night (out of sight of his stepfather and stepbrothers, who disdain his interest in art); this habit of working through the night remains constant throughout his life. In high school, Olitski works with oil paint for the first time, painting landscapes en plein air around Sheepshead Bay with Russian-born Impressionist Samuel Rothbort [1882–1971]. In his final year of high school, he wins a scholarship to study drawing at the Pratt Institute, and upon graduation receives a special prize for art.

1940–1949 In 1940, Olitski is admitted to the National Academy of Design on Amsterdam Avenue at 109th Street, where he studies life drawing and portrait painting with Sidney Dickinson [1890–1980]. In the evenings, he studies sculpture at the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design on East Forty-fourth Street. During this time, Olitski frequently visits museums and develops an interest in Impressionism and Fauvism. Drafted into the United States Army in 1942, Olitski becomes a U.S. citizen and legally takes his stepfather’s name, Olitsky. After being discharged in 1945, he marries Gladys Katz that same year and in 1948, his first daughter, Eve, is born. During this time, Olitski continues training in art, studying sculpture in 1947 under Chaim Gross [1902–1991] at the Educational Alliance at 197 East Broadway (fig.1). Two years later, Olitski moves to Paris on the GI Bill. Though his goal is to learn to paint in the style of the Old Masters that kindled his interest in art, he reads articles on modern art by Clement Greenberg in Partisan Review before heading to France. He studies first with sculptor Ossip Zadkine [1890–1967], then at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. He maintains a studio in Chaville, a woodsy suburb southwest of Paris, and later on the rue des Suisses, near the Plaisance metro station, in the 14th arrondissement of Paris. In an attempt to work against his now advanced academic facility, Olitski paints blindfolded, creating a series of nightmarish abstract portraits composed in bold colors and flat planes (fig.2).

1950–1959 In Paris, Olitski meets sculptor Sidney Geist, who is involved with a young American artists collective that includes Al Held and Lawrence Calcagno. Together, this group opens Galerie Huit on the Left Bank on rue Saint-Julien-lePauvre, where Olitski has his first solo exhibition in 1951, showing works developed out of his blindfold paintings. After returning to New York later that year, he studies art education at New York University, earning a Bachelor of Science in Art Education in 1952 and an MA in that field in 1954. Inspired by used drawing boards he finds in the school’s art studios, he works in 1955 on monochromatic paintings in which all pictorial incident is pushed to the edges of the picture. He explores that composition at the same time in a series of etchings. His habit of translating compositions and effects across a variety of media continues throughout his career (figs.3 and 4). The relationship between pictorial drawing and the boundaries of the picture format will remain a preoccupation of Olitski’s for decades to come.

Fig.3 Jules Olitski. Drawing Board Echo, 1952. Spackle, acrylic resin, and dry pigments on canvas, 30 x 30 in. (76.2 x 76.2 cm). Private Collection.

Fig.4 Jules Olitski. Drawing Number One (Third State), 1956. Soft ground etching/drypoint and aquatint from one copper plate, 4 7⁄8 x 5 7⁄8 in. (12.4 x 14.9 cm). Estate of Jules Olitski.

Fig.5 Postcard from Clement Greenberg to Jules Olitski, dated April 10, 1958 (recto and verso).

Fig.6 Jules Olitski. Whore of Babylon,1958. Spackle, acrylic resin, and dry pigments on canvas, 73 x 59 in. (185.4 x 149.8 cm). Collection of David and Audrey Mirvish, Toronto. Though he occasionally exhibits work in group shows around New York—at Roko Gallery and the City Center Art Gallery—his work remains virtually unknown. While teaching art at SUNY New Paltz during 1954–55, Olitski continues working towards his doctoral degree at NYU, where he serves as curator of the University’s Art Education Gallery, later to become the Grey Art Gallery. In 1956, he joins the faculty of the C.W. Post Campus of Long Island University in Greenvale, New York, where he becomes Chairman of the Fine Arts Department. He marries his second wife, Andrea Olitsky (née Pearce) in January 1956 then moves to Long Island—first to Oyster Bay, where his daughter Lauren is born in 1957, then on to Northport. He spends that summer with his family at Sister Island on Lake Wentworth in Wolfeboro, New Hampshire, and sets up a studio on nearby Stamp Act Island, returning there annually until the early 1970s. Eager to have his paintings shown in New York, Olitski meets with gallerists Charles Egan, John Bernard Myers, and Elinor Poindexter, each of whom compliments and encourages his work but is unwilling to exhibit it. Desperate for an exhibition, Olitski hatches a plan, recounted in his essay “My First New York Show”:

I would invent an artist: the more dramatic his history, the better. A kind of ghost artist: no one could ever see him in the flesh but me. So then: Jevel Demikov, a talented young Soviet artist. . . . At the college [C.W. Post], I scheduled an exhibition called L’École de Paris Aujourd’hui. I borrowed paintings for the exhibition from some of the galleries in New York. . . . When the show ended I drove to the city to return the paintings. My first stop, as it happened, was the Alexander Iolas Gallery. [Reading the exhibition checklist, Iolas] stops short and looks at me. “Who is this Demikov?” . . . I bring the paintings in and lean them against a wall. . . . Finally Iolas stands, straightens up, turns around, looks me in the eye, and says: “You’re right. He’s a genius. We must have a show.” [Finding that Iolas is unwilling to exhibit work without meeting the elusive Demikov, a frantic Olitski thinks:] What to do? Tell the truth. There’s no other way. But I can’t say it in English. I give a sign and say, “Alors, Demikov, c’est moi.” I think at that moment Mr. Iolas was not sure [whether] I was an escaped Russian or a lunatic American. About eight months later Mr. Iolas gave me first my New York show.2

His work is shown in Iolas’s contemporary art space, the Zodiac Room, in 1958. The gallery misspells his name as “Olitski,” which the artist subsequently retains. From a friend, he hears that Clement Greenberg had seen the show and spoken favorably about it. Olitski writes to the critic who responds with an invitation to visit (fig.5). After their meeting, Greenberg invites him to participate in a December 1958 group show at French & Company. The following May, Olitski has a solo show at that gallery, exhibiting twenty-six paintings from the previous year. Painted mostly in shades of gray and earthen browns and reds, their massive, impastoed forms and bold figure/ ground compositions are unlike the allover gestural abstractions of his Parisian peers Al Held and Joan Mitchell. The surfaces of his paintings are dense and sculptural, comprised of spackle, acrylic resin, and dry pigment (fig.6). Shortly after this exhibition, Olitski makes a significant change in his painting practice. While still drawing inspiration from organic shapes in general and the female form in particular, he begins using boldly colored dyes to stain the canvas weave (fig.7).

Fig.8 Installation view of Osculum Silence (1960) in Recent Acquisitions; at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, November 20, 1962–January 13, 1963.

Fig.10 Jules Olitski exhibition at the Galleria Santa Croce, Florence, February 1963. Left to right: Untitled – Thirteen (1963); Lucy’s Fancy (1960) hung vertically; and Doll Walker (1961) hung horizontally.

Fig.11 Installation view of the exhibition Ausstellung Signale at Kunsthalle Basel, June 26–September 5, 1965. Left to right: The Prince Patutszky – Red (1962) and One Time (1964).

Fig.12 Poster for Jules Olitski, exhibition at Poindexter Gallery, New York, March 10–March 28, 1964.

Fig.13 Jules Olitski in front of his home, South Shaftsubury, Vermont, 1966. 1960–1964 In his second solo exhibition at French & Company, in the spring of 1960, Olitski shows seventeen of his recent dye paintings. Shortly after, the gallery closes its contemporary program, and Olitski is taken on by Elinor Poindexter (fig.12). In 1961, his painting Osculum Silence wins an award at the Pittsburgh International Exhibition of Contemporary Painting and Sculpture (renamed in 1982 as the Carnegie International) held at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh. The painting is bought by G. David Thompson and gifted to the Museum of Modern Art, New York, soon after (fig.8). Subsequently, he shifts from dyes to acrylic paints, Liquitex and Magna. Though he thins Magna with turpentine and paints with sponges and rollers, Olitski’s paintings of the early 1960s are unlike those of other artists using the “soak-stain” technique. He avoids autographic gesture as well as symmetry and geometry, using ovoid and elliptical forms. His palette comprises contrasting tertiary colors: salmon next to chartreuse, lavender against lemon yellow, teal bands orbiting mauve on a turquoise

background—hues pungent, tart, and saccharine by turns (fig.9). Olitski’s concern, art critic Michael Fried observes, is with “mutually repulsive rather than attractive relations between colors.”3 His persistence in challenging the limits

Fig.9 Announcement card for Jules Olitski exhibition, Royal Made, Yellow, at Poindexter Gallery, New York, 1962, with Olitski’s re-titling of The Julius Dmikhovsky Image.

of “good” or “acceptable” taste mirrors that of contemporaneous Pop artists. In 1962, Greenberg notes the “shocked distaste” that Olitski’s work elicits in the art world.4 Nevertheless, his cellular-form stain paintings are shown in three exhibitions throughout Italy in 1963 (fig.10). By this time he has pushed his painting toward two opposite extremes: in pictures such as Golubchik – Purple and The Prince Patutszky – Red (both 1962), curving and organic forms are magnified, seeming alternately to extend past, or emerge from, the edges of the canvas; at the same time, in paintings like Dream Lady (1963) and One Time (1964), colors are suspended within or framed by expanses of unpainted canvas (fig.11). In both manners, Olitski’s overriding concern is with the bounding edges of the canvas.

In 1963, Olitski joins the faculty of Bennington College. Located in rural southern Vermont, Bennington in the 1960s is an outpost for art and literature—painter Paul Feeley heads the visual arts department, which includes British sculptor Anthony Caro and, occasionally, painter Kenneth Noland. Bernard Malamud and Howard Nemerov teach in the literature department. Olitski purchases an early nineteenth-century Federal-style home in nearby South Shaftsbury. He moves two barns behind the house together to create his largest studio space to date (fig.13). The following year, he is included in Post-Painterly Abstraction, a forward-looking exhibition curated by

Fig.14 Jules Olitski. Fatal Plunge, 1963. Magna acrylic on canvas, 97 x 68 in. (246.4 x 172.7 cm). Collection of the Saint Louis Art Museum. Clement Greenberg for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. In his catalogue essay, Greenberg emphasizes the “openness and clarity” of design and “high keying [and] lucidity” of color common to recent abstract painting.5 Olitski’s paintings of 1963–64 continue his exploration of color forms and their relation to the boundaries of the canvas; though his compositions have become more straightforward, their visual effects are manifold. In Fatal Plunge Lady (1963, Pl. p.67) and other “Curtain” paintings, contrasts in color remain brilliant and dramatic despite disparities in size, as the trajectory of the forms guides one’s eye down the canvas. One of his main concerns is to seamlessly blend different shades, like the darkening blues of Fatal Plunge (fig.14), or contrasting hues into one another, as in the dramatic shift from viridian to red in Emma Amour (fig.15). Olitski’s “Curtain” paintings are showcased in Three American Painters: Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, Frank Stella, an exhibition curated by Michael Fried at Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum in 1965. In his catalogue essay, Fried rigorously details the pictorial innovations of Olitski’s pictures and their implications for future abstract painting. Between 1964 and 1966, Olitski establishes relationships with several dealers that will represent him for decades to come—John Kasmin in London, David Mirvish in Toronto, and Andre Emmerich and Lawrence Rubin in New York.

1965–1969 At Bennington, Olitski and Caro bring a group of students to visit Kenneth Noland’s studio (fig.16). Caro says “that what he wants to emphasize in his sculpture is the materiality, the density of the medium.” Olitski replies, half-jokingly, that “what I was looking for was the complete opposite: a spray of color in the air that stayed there, suspended. Just that.”6 Haunted by this vision, Olitski acquires an air compressor spray gun and embarks on a new method of painting. He lays a length of unstretched, unsized canvas on the floor and sprays colors into each other and across the surface, determining the size and shape of the painting afterward by cropping the edges from the larger canvas. The abrupt color transitions and discrete shapes in his stained “Curtain” paintings of 1964 give way in the spray paintings to interpenetrations of dense shadow and diaphanous light, volume and mass, pictorial space, and material surface. The sprayed surfaces of Olitski’s paintings “[contrive] an illusion of depth that somehow extrudes all suggestions of depth back to the picture’s surface,” Greenberg writes. “It is as if that surface, in all its literalness, were enlarged to contain a world of color and light differentiations impossible to flatness but which yet manage not to violate flatness.”7

Fig.15 Jules Olitski. Emma Amour, 1964. Enamel and pastel on canvas, 137 x 82 in. (347.9 x 208.2 cm). Collection of Audrey and David Mirvish, Toronto.

Fig.16 Jules Olitski and Kenneth Noland in the latter’s home, South Shaftsbury, Vermont, 1964.

Fig.17 Helen Frankenthaler (center) on gondola with (clockwise from bottom left) Lady Dufferin and Sheridan Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood, 5th Marquess of Dufferin and Ava, Jules Olitski, gondolier, Anthony Caro, John Kasmin, and Richard Smith, Venice, Italy, 1966.

Having escaped the inevitability of linear drawing in his spray paintings, Olitski recognizes that the edge of the canvas is itself an act of drawing—a painting’s “outer edge is inescapable,” he writes. “I recognize the line it declares as drawing. This line delineates and separates the painting from the space around, and appears to be on the wall.”8 To this end, Olitski experiments with different manners of enunciating that line, primarily by reiterating the outer edge inside the painting, along its perimeter, with contrasting color in pastel or impasto. In February 1966, Olitski is one of four American artists selected by the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Curator of American Art Henry Geldzahler to exhibit at the XXXIII Venice Biennial that June (fig.17). Early the following year, his spray painting Pink Alert (fig.18) wins first prize at the 30th Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, where his first solo museum exhibition is held later that spring. In June 1967, Olitski moves to 323 West Twenty-first Street in Chelsea, setting up a studio there shortly after. Throughout the late 1960s, Olitski experiments with paints of heightened viscosity and with broader spray gun nozzles that can be adjusted from a fine mist to a large splatter. These materials yield paint surfaces that are increasingly thick and opaque. In other paintings of this period, he adds pearlescent powder or varnish to the pigment in order to create surfaces that radiate like neon. En route to the French Riviera in the summer of 1968, Olitski stops in London to visit Anthony Caro, who encourages him to try his hand in that medium. With Caro’s help, he finds an unused factory in St. Neots, a small village twenty miles east of Cambridge, and works there with sheets of fabricated aluminum—a material light enough for him to handle, move around, and compose. He completes twenty sculptures in seven weeks between July and September. Geldzahler visits him in St. Neots and, impressed with the work, offers Olitski an exhibition of the sculptures. When The Sculpture of Jules Olitski opens in April 1969, Olitski becomes the first living American artist to be given a solo show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig.19).

1970–1979 In the summer of 1970, Olitski works with the Chiron Press to execute a series of silkscreens. The ten completed prints are published as Graphics Suite #1 and Graphics Suite #2 by Waddington Graphics in London. Commenting on these works, the art critic and curator Karen Wilkin observes that “Olitski seems to have treated the silkscreen process as a tool not unlike his spray gun: a mechanical means of producing a visual effect that is in no way mechanical.”9 In the spring of 1971, Olitski moves his studio to a large loft at 827 Broadway, just south of Union Square. Museum of Modern Art curator William Rubin and painter Paul Jenkins also reside in this building. Olitski experiments with newly developed acrylic gels, which he uses to stiffen and seal the canvas surface, and with polymers that extend opaque paints into translucent glazes. Using rollers and squeegees, he works in a drab palette of neutral colors on thin, subtly inflected membrane-like surfaces (figs.20 and 21).

Fig.18 Jules Olitski. Pink Alert, 1966. Acrylic on canvas, 113 x 80 in. (287 x 203.2 cm). Collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Fig.19 Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, April 1969, front cover showing detail of the sculpture Heartbreak of Ronald and William (1968).

Fig.20 Jules Olitski in his Broadway studio, New York City, February 1974.

Fig.22 Jules Olitski, Clement Greenberg, and Kenneth Noland in Olitski’s North Bennington sculpture studio (Ludlow Bunkhouse), Vermont, ca. 1970s.

Fig.23 Jules Olitski standing inside sculpture in progress (Greenberg Variations), South Shaftsbury, Vermont, 1974.

Fig.24 Shechinah Temptations (1976) on the front cover of the catalogue for Jules Olitski: New Sculpture, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1977. In the fall of 1973, Olitski gifts his South Shaftsbury home to Bennington College in exchange for lifetime use of a property the college owns in North Bennington, the Ludlow Bunkhouse, where he works on sculpture throughout the 1970s (fig.22).10 He works briefly with mild steel before switching to Corten; as in his early 1960s paintings, circular forms predominate. While the earliest “Ring” sculptures, completed in the summer of 1972, rise only ten inches off the ground, the next series develops in height to over five feet (fig.23). Later in the decade he stacks sheets of corrugated, curved, and arcing steel in configurations up to ten feet high. This body of work is the subject of a museum exhibition that travels from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC, in 1977 (fig.24).

Olitski’s first full retrospective is organized by Kenworth Moffett in April 1973. The exhibition premiers at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, then travels to the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, before concluding at the Pasadena Art Museum in California (fig.25). Reviewing the exhibition in Time magazine, Robert Hughes asserts that “Olitski is a force to be reckoned with. He has next to no public face, for he prefers the quiet of his huge loft-studio on lower Broadway—out of which comes an undistracted flow of work.”11 Thomas Hess observes the paradoxes evident in Olitski’s work: “between chance and control . . . between the substantial and the ephemeral.” The artist is positioned “at the interface of history—between the Old World and the New, Demikovsky and Olitski, old-master virtuosity and color-field modernism.”12

After his divorce from Andrea Olitsky, he purchases a home on Bear Island on Lake Winnipesaukee near Meredith, New Hampshire. In 1974, he completes the construction of a large studio on the property, working there through the summer and fall. In a rush of creative energy and experimental curiosity, Olitski begins working in several painterly manners at once, employing an ever-expanding variety of acrylic mediums to thin the consistency or thicken the texture of his paint (fig.26). He uses mops, brooms, and trowels to pour and spread materials. The paintings increasingly resemble natural phenomena—luminosity, cascades, erosion. As in nature, the effects that emerge in these paintings are as diverse and multitudinous as they are particular and miniscule. Two senses of painterly scale—broad gesture and infinitesimal detail—operate simultaneously, each reinforcing the

Fig.25 Installation view of Jules Olitski traveling retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 7–November 4, 1973. Left to right: C + J + B (1966), Third Indomitable (1970), and Fifth Omsk Pleasure (1972).

Fig.26 Jules Olitski in his Broadway studio, New York City, November 1972.

Fig.27 Jules Olitski. Repahim Shade – 2, 1974. Acrylic on canvas, 90 ½ x 120 in. (229.9 x 304.8 cm). Private Collection.

other by coincidence and contrast. Between 1974 and 1975, his most prolific years, Olitski explained, “methods and techniques I’d abandoned, such as underpainting, modeling, half-tones, impasto, chiaroscuro, tinting, glazing, and so forth, found their way back into my work”(figs.27 and 28).13 During the mid- to late 1970s, he spends half the year (roughly April through October or November) in New Hampshire, and the other half in New York City. Early in 1975, he meets Kristina Gorby (née Fourgis), whom he will marry five years later, on February 29, 1980. Accepting an award from the University of South Carolina, Columbia, in March 1975, Olitski offers what amounts to an artist statement:

The artist’s function, his reason for being, lies solely in the making of the work, the inventing of the work. The painter strives to make [his vision] real by what he does with the materials available to him. Every decision the painter makes must be in accord with the attempt to realize that vision—the vision he has of what painting is, or must be. I mean this in even the most prosaic sense: the choice of kinds of paint, colors, medium, brushes, canvas, or possibly paint rollers, mops, sponges, or whatever. The selection of materials and what is done with them are all in the service of the artist’s vision, dictated by that vision. . . . So I think curiosity, the urge to discover, the incitement of a major challenge, the will to impose one’s artistic vision so that we all see and experience differently than before—all these have to do with making art.14

His momentum continues into 1976, as he shows stoneware and clay works made in Syracuse at the invitation of ceramic artist and curator Marjorie Hughto. He exhibits life drawings at Noah Goldowsky Gallery in New York, works on steel sculpture in the summer, and has solo exhibitions of paintings in Toronto, Vienna, New York, and Houston. He purchases a home on Islamorada, Florida, in the Florida Keys, in April 1978. After closing his Broadway studio in 1980, Olitski will continue to spend spring, summer, and autumn on Bear Island and winter in Florida for the rest of his life. In a review near the end of the 1970s, acclaimed poet and art critic John Ashbery muses about Olitski’s increasingly lush and sensuous recent work:

By now any doubt as to [Olitski’s] position as one of our leading abstract painters should be swept away by the sheer weight and authority of [his recent] paintings. . . . [O]ne sign of Olitski’s genius, I think, is that he makes it almost impossible to describe his work in words. Colors, shapes, textures, demand a vocabulary that doesn’t exist yet, and perhaps never will—a sure sign that the life of this work is in the work itself and not in danger of being drained out of it by critics. His new paintings, especially, stake out a claim to a territory that is beyond criticism, a place that looks like outer space but is also as near and as lively as dreams.15

Fig.28 Jules Olitski. Third Manchu, 1974. Acrylic on canvas, 84 x 49 in. (213.4 x 124.5 cm). Estate of Jules Olitski.

Fig.29 Jules Olitski. Second Broom of Joseph, 1980. Acrylic on canvas, 38 x 89 ½ in. (96.5 x 227.3 cm.) Private Collection.

Fig.31 Jules Olitski. Silent Pass, 1986. Acrylic and oil-based enamel on Plexiglas, 49 x 79 in. (124.4 x 200.7 cm). Estate of Jules Olitski.

Fig.32 Jules Olitski. Rake’s Progress – 4, 1987. Acrylic and oil-based enamel on Plexiglas, 69 x 69 in. (175.3 x 175.3 cm). Private Collection.

Fig.30 Jules Olitski. Padua Rim, 1985. Acrylic on canvas, 67 ½ x 35 in. (171.4 x 88.9 cm). Estate of Jules Olitski.

1980–1989 In his paintings of the early to mid-1980s, Olitski continues to refine and extend the techniques developed in the previous decade in colors increasingly moody and dramatic. Though he continues to work with brooms, mops, spray guns, squeegees, and other unconventional tools, he isolates certain painterly effects more separately in narrow-formatted canvases. For example, one broad sweep of ultramarine blue covers most of the surface of Second Broom of Joseph (1980); it shifts in luminosity as a coating of black spray thins to a haze across the surface (fig.29). The use of darkly colored sprays as sfumato (that is, the softening of color transitions without lines or borders) and softly glowing lambent surfaces characterize Olitski’s work of this period (fig.30). In 1983, Riva Yares mounts her first exhibition of Olitski’s work in Scottsdale, Arizona. She recalls her first meeting with the artist:

When I arrived at the island, there was Olitski, a large man with soft eyes, holding a big glass of Scotch, at ten in the morning. I liked him immediately. . . . He was just about to go to sleep, as it was his habit to work at night and sleep during the day. We met again for dinner, and then after dinner everybody went to sleep except Olitski and me. We stayed by the dinner table and talked all night. . . . We shared the awe of nature’s wonder, spoke of doing things by intuition and feeling.16

Anna Olitsky, his mother, dies in October 1982. In the summer of 1984, Olitski’s work is the subject of a retrospective at the Fondation du Château de Jau in Perpignan, in the center of the Roussillon plain on the Mediterranean coast. The following spring, several of his paintings are shown in Grand Compositions, a selection of art from the collection of David Mirvish exhibited at the Fort Worth Art Museum. In 1986, he begins painting almost exclusively on irregularly shaped sheets of Plexiglas, spreading pastel hues into frosty metallic pigments and iridescent gels, slathering them across the surface in dense and opaque configurations. Sprays of dark pigment yield areas of shadow and spatial recession (fig.31). In January of that year, Yares Gallery stages a retrospective of his work, showing over thirty-five paintings of the previous two decades. In 1987, with a series of works on tinted, mirrored Plexiglas, Olitski mounts his most aggressive challenge yet to “good” or “acceptable” taste. Despite their radical and unprecedented appearance, these paintings allow Olitski to continue in his pursuit of radiant color and light that seem to glow from within. In Rake’s Progress – 4 (fig.32), for example, Olitski smears and smudges lipstick reds and gaudy splatters of pearlescent white over a reflective sapphire-blue diamond of Plexiglas. Concurrently, he completes a series of sculptures in Plexiglas painted with acrylic and enamel; their stacks of corrugated and arcing forms are reminiscent of his works of the late 1970s, though smaller in size than his earlier

Fig.33 Announcement for Jules Olitski: New Sculpture at Andre Emmerich Gallery, March 1987. Return of Ea (1986) shown on cover.

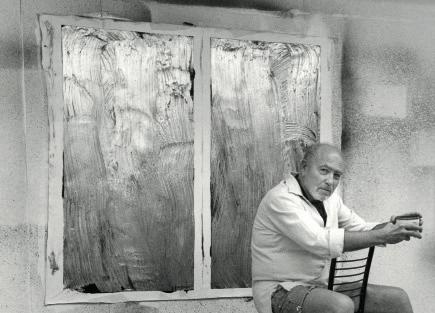

Fig.34 Jules Olitski in his studio, Islamorada, Florida, 1985. sculpture. They are shown at Galerie Wentzel in Cologne, Yares Gallery in Scottsdale, and Andre Emmerich in New York (fig.33). During the next several years, many of them are translated into mild steel. Olitski is commissioned by Philadelphia’s Institute of Contemporary Art to execute an edition of prints for their 1986 fundraiser. He collaborates with printers at the Brandywine Workshop, where he will return for their Visiting Artist Series to create five subsequent print editions over the next three years. These and earlier prints are collected in a retrospective organized by the Associated American Artists gallery in New York later in the decade. Olitski is appointed Milton Avery Distinguished Visiting Professor at Bard College in the fall of 1987, where, it is reported, he speaks in “lucid, unpretentious terms . . . humble in approach, rich in wit and genuine in intent,” telling students to “use intuition, intelligence, experience, and inspiration to make art, but not to think too much about the process of creating.”17 (fig.34)

In 1988, Olitski brings into the studio a painter’s mitt that his wife had purchased to paint an iron fence on their property. The mitten is made of fuzzy polyester and textured like a paint roller. He uses it to spread an array of warm-toned hues, iridescent metallic pigments, thick acrylic gels, and newly developed interference colors into one another. Interference paints are transparent and pearlescent, shifting in hue and radiance in relation to the light that is refracted through them. Blending the pigments into thick applications of transparent gel allows light to pass through and stay captured within the paint surface. When this light reflects back outward, the pigments “interfere” with its color and luminosity.18

Olitski’s painterly gestures remain legible throughout the “Mitt” pictures; he sculpts the effulgent paint surface into hairpin crests and ridges. To amplify effects of space and volume, he sprays the painting with dark pigment laterally and from a low angle, where it catches the contours of the surface and accumulates arounds its ridges. From different angles a single gesture seems alternately to shimmer and glow or to curl into darkness, engulfed by shadow (fig.35). Though Olitski’s magisterial paintings of the late 1980s are little understood by critics, Sidney Tillim contextualizes them in the main currents of 1980s art world in an article entitled “Ideology and Difference,” writing:

The way things work ideologically today, Koons’s stuff is supposed to represent the last word in postmodernism’s disposal of the modernist kind of thing made by Olitski, which is perceived as lacking social and political resonance, not to mention its alleged formal conservatism. But they are both rapturously anarchic artists . . . , [sharing] an aptitude for color and texture that are wondrously tawdry in different ways, but which are identical as metaphors of absolutized sensation, literalizations of uncommon taste. The hysterical reaction against Koons . . . has not, as I write, resulted in any grateful acknowledgement that Olitski upholds just those values that Koons’s critics feel he has debased. Precisely, Olitski is just as subversive an artist, in that he continues to flaunt his taste as a way of preserving art from the blandness that has been its usual destiny as the bourgeois decades accumulate.19

Fig.35 Jules Olitski. Eternity Domain, 1989. Acrylic on canvas, 68 x 107 in. (172.7 x 271.8 cm). Private Collection.

Fig.36 Jules Olitski. Flare, 1993. Acrylic on canvas, 40 x 48 in. (101.6 x 121.9 cm). Private Collection.

Fig.37 Jules Olitski working with master printer Catherine Mosley on the aquatint Beauty of Angels in his Bear Island Studio, on Lake Winnipesaukee, New Hampshire, August 1989.

Fig.38 Jules Olitski. Eos Flow, 1996. Watercolor and pastel on all rag paper, 22 x 30 in. (55.9 x 76.2 cm). Private Collection.

1990–1999 Olitski continues working in the manner of the “Mitt” paintings, finding affirmation and inspiration in his experience of the work of Old Masters, especially El Greco, whose Virgin of the Immaculate Conception (1607–1613) affects him profoundly during a trip to Spain in 1990. Asked about the changes in his work over the past decade, Olitski stresses the continuity of his vision, explaining that “one thing leads to another. . . . [I]n making the work, sometimes something unexpected happens. And I don’t know what to make of it. I’m made restless by it and I have to do it more and see what happens. And that, in turn, leads to a seemingly new development. But it’s all in [the] context of a vision, of making it real.”20 The painterly gestures in Olitski’s “Mitt” paintings were expansive; by contrast, his 1993–94 paintings, though they resemble the earlier “Mitt” pictures, are chaotic and compressed. In these paintings, afferent scrawls of pale, close-valued, metallic tones are splattered with pigments that contrast starkly in color and texture, giving the impression, as painter Walter Darby Bannard observes, “that the whole set of marks is hanging in mid-air, suspended . . . .”21 (fig.36). In the spring of 1994, Olitski, Kenneth Noland, and Anthony Caro are invited to participate in the Hartford Art School’s International Distinguished Artists Symposium, where they give master classes for students and lectures for the public. Olitski works in Hartford’s print studio, completing a series of abstract monoprints, a medium that he will continue to explore for the next decade (fig.37). Eventually, he has a printmaking studio built next to his main studio on Bear Island, where he shifts to monotyping—the most direct manner of printmaking, well-suited to his experimental, intuitive style.

By chance he sees a postcard reproduction of Eugène Delacroix’s oil painting La mer à Dieppe (The Sea at Dieppe),1852, in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which catalyzes and affirms his impulse to paint from nature. “I was seized by this painting,” he says. “Somehow it gave me heart that I could do this.”22 As it happens, both his Bear Island studio and his Islamorada home are waterfront and west facing. He converts a small porch in his New Hampshire house into a watercolor studio, and, in a surge of creative energy, begins painting landscapes and seascapes both real and imagined. Working on paper in watercolor, pastel, oil stick, and gouache, as well as acrylics on canvas, Olitski dedicates virtually all his energy to work in landscape for the next several years (fig.38). Though the scale and subject of his work seems to have changed dramatically, Olitski makes little distinction between abstraction and representation. “I sense reality as a kind of flow, emerging from a core,” he says. “My job as an artist is to give it life. It’s the vision of the artist, the core. I think of something G.K. Chesterton wrote, ‘Behind every artist’s mind there is a certain pattern, an architecture, a design. It’s a thing, like the landscape of his dreams.’ For all artists, no matter the medium, the vision expresses his reality.”23 To that end, he brings the same spirit and passion to his small-scale landscapes on paper as to paintings several times that size.24 Olitski’s work slides seamlessly between abstract and representational modes, often blending the two together in a painterly synthesis of naturalistic effects. The radiant sun suspended near the center of Hierarchy of Light (1998, fig.39) resonates as naturalism as much as the dramatic abstract tenebroso of Once in Segovia (1999, fig.40). The attitudes common to art made in the 1990s are ironic distance and abject debasement. In contrast, Olitski’s landscapes are romantic, resplendent—the work of a man standing in awe and humility before Creation.25 Of Olitski’s landscapes Michael Fried writes, “There is not the merest touch of ego to be seen.”26

Fig.39 Jules Olitski. Hierarchy of Light, 1998. Acrylic on canvas, 60 x 72 in. (152.4 x 182.9 cm). Private Collection.

Fig.40 Jules Olitski. Once in Segovia, 1999. Acrylic on canvas, 36 x 48 in. (91.4 x 121.9 cm). Collection of Audrey and David Mirvish, Toronto.

2000–2007 Following a diagnosis of lung cancer in September 1999, Olitski undergoes chemotherapy, radiation, and, ultimately, a major surgery in January 2000. He emerges from the operation positively vital, returning to his studio soon after and embarking on paintings in which the glimmering sunrises and sunsets of his landscape pictures are transformed into massive orbs of bold color, molten and mottled, set among empyrean fields. Though he continues to create landscapes on paper for the rest of his life, his paintings remain entirely abstract. There is little trace of the artist’s hand in these paintings; they seem to thunder forth with cosmic energy. The 2002 series title “With Love and Disregard” captures the vision behind Olitski’s late work, in which he “gives us nothing but paint, paint

applied with reckless disdain for our learned ideas of what a painting should look like”(fig.41).27 In Temptation: Yellow (2002), ferociously contrasting colors boil across a stormy surface, with rumbling textures cracking open, electrified. The painting’s energy seems unbounded (fig.42). Nevertheless, Olitski is an artist against his time. For decades he has worked by the seventeenth-century French painter Nicolas Poussin’s mantra, “The goal of art is delight.” In his unyielding quest for aesthetic delight, or “pleasure,” he recognizes his countercultural position. “One risks being called a fascist for seeking excellence and having pleasure in the beautiful,” he warned. “[Quality] simply isn’t democratic. It attacks the modern perception of equality, diversity, multiculturalism . . . .”28 Likening the situation to the “Roman circuses of old,” he observes, “Abominations are the order of the day. . . . The public must be fed its daily outrage.”29 As insouciant in his abstract painting as he is romantic in his landscapes, Olitski makes his love for art and disregard for orthodoxy inspirational: “Creative energy can thrive when there is a culture to go up against.”30 In addition to his resurgent painting practice, he continues working in a variety of traditional media: painting and drawing from nature; making monotypes, life drawings, and sculpture; aiming always to create art of the highest caliber (fig.43). “What motivates the art that presently prevails?” he wonders. “I suppose a hatred for our traditions, for excellence, a reflexive self-hate. . . . In the face of our present culture, I say to myself, ‘Expect nothing. Do your work. Celebrate!’”31

Olitski continues working until the end of his life. “Toward the very end, in the hospital” Michael Fried recounts, “one of Jules’s doctors asked him whether or not he wanted heroic measures taken to extend his life. ‘Of course I do,’ Jules is supposed to have said. ‘I still have work to do.’”32 Jules Olitski dies on February 4, 2007, aged 84.

Fig.41 Jules Olitski. With Love and Disregard: Zeus, 2002. Acrylic on canvas, 60 x 84 in. (152.4 x 213.4 cm). Collection of the Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

Fig.42 Jules Olitski. Temptation: Yellow, 2002. Acrylic on canvas, 60 x 72 in. (152.4 x 182.9 cm). Estate of Jules Olitski.

Fig.43 Jules Olitski in his Bear Island studio, on Lake Winnipesaukee, New Hampshire, September 2005.

My thanks to Lauren Olitski Poster for her generous energies and collaborative spirit. Her encyclopedic memory was invaluable to this project. In addition, I have made use of the chronology by Elinor L. Woron and Kenworth Moffett in Moffett’s 1981 monograph on Jules Olitski.

1. The Demikovsky family was originally from Gomel in present-day Belarus, then part of Soviet Russia. Their move to Snovsk may have been prompted by the elder Jevel’s being stationed there in his role as a commissar, or due to his arrest and imprisonment.

2. Jules Olitski, “My First New York Show,” Partisan Review, vol. 56, no. 1 (Winter 1989): 34–44.

3. Michael Fried, “Jules Olitski,” in Art & Objecthood: Essays and Reviews (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 136.

4. Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism, ed. John O’Brian, vol. 4, Modernism with a Vengeance 1957–1969 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 34.

5. Greenberg, “Post-Painterly Abstraction,” in Collected Essays and Criticism, Volume 4, 196.

6. Jules Olitski, “An Interview with Jules Olitski,” by Louise Gauthier, Perspectives 8 (Spring 1990): 78.

7. Greenberg, “Introduction to Jules Olitski at the Venice Biennale,” in Collected Essays and Criticism, Volume 4, 230.

8. Jules Olitski, “Painting in Color,” reprinted in Jules Olitski by Kenworth Moffett (New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams, 1981), 214.

9. Karen Wilkin, “The Prints of Jules Olitski,” in The Prints of Jules Olitski: A Catalogue Raisonné 1954–1989 (New York, NY: Associated American Artists, 1989), 13.

10. Bennington College sold the South Shaftsbury residence within a couple years. Subsequently, the College decided in 1988 that Olitski’s “lifetime use” of the Ludlow Bunkhouse should come to an end.

11. Robert Hughes, “Color in the Mist,” Time, July 16, 1973.

12. Thomas B. Hess, “Olitski Without Flattery,” New York, October 1, 1973, 77.

13. Jules Olitski, “The Courage of Conviction,” in The Courage of Conviction, ed. Phillip L. Berman (New York, NY: Ballantine Books, 1985), 189.

14. Jules Olitski, “Speech delivered at the University of South Carolina, Columbia, March 27, 1975,” in Olitski by Moffett, 218–220, edited for clarity. 15. John Ashbery, “John Cage and Jules Olitski,” in Reported Sightings: Art Chronicles 1957–1987, ed. David Bergman (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989), 223–224

16. Riva Yares, excerpts compiled from Jules Olitski Selected Paintings: 1962–1985, A Retrospective View, exh. cat. (Scottsdale, AZ: Yares Gallery, 1986), 2; and “In Memory of Jules Olitski,” in Jules Olitski: Radiance + Reflection, exh. cat. (Santa Fe, NM: Yares Art Projects, 2013), n.p.

17. Florence Panella, “Jules Olitski, Bard’s Distinguished Professor…” Poughkeepsie Journal, October 13, 1987, 13A.

18. For this description, I am indebted to Darryl Hughto for his technical expertise.

19. Sidney Tillim, “Ideology and Difference,” Arts, March 1989, 48–51, edited for clarity.

20. Jules Olitski, “Interview with Jules Olitski,” Gauthier, 77–78, edited for clarity.

21. Walter Darby Bannard, “Jules Olitski at the New Gallery,” in Olitski (Miami, FL: University of Miami, 1994), n.p.

22. Jules Olitski, “Jules Olitski,” interviewed by William V. Ganis, Art Criticism, vol. 14, no. 1 (1999): 40.

23. Jules Olitski, “Expect Nothing, Do Your Work, Celebrate: Derek Sprawson talks to Jules Olitski,” in Jules Olitski (Nottingham, UK: Future Factory Far Ahead, 2000), 14.

24. Olitski, “Jules Olitski,” interviewed by Ganis, 39.

25. “I believe in a Creator. . . . Of course, nothing can be proven about the existence of the Creator. I can have no certainty, only belief,” Olitski wrote in “The Courage of Conviction.”

26. Michael Fried, “Fields of Color,” Artforum, April 2007, 56.

27. Walter Darby Bannard was describing Olitski’s 1993–-94 paintings, but the description is perhaps even more apt for the later work. Bannard, Olitski, n.p.

28. Jules Olitski, “Barley Soup and Art—High and Low,” contribution to “What Happened to the Arts?” Partisan Review, vol. 69, no. 4 (Fall 2002): 607.

29. Ibid.

30. Jules Olitski, “How My Art Gets Made,” Partisan Review, vol. 68, no. 4 (Fall 2001): 623.

31. Olitski, “Barley Soup and Art,” 609; and “How My Art Gets Made,” 623.

32. Fried, “Fields of Color,” in Artforum, April 2007, 56.