13 minute read

A Song for Two Hands

from Heritage_46

Dr. Tim McNeese, Professor of History

During its 132-year existence, nothing altered the history of York College more than an aberrant spark in the attic of Old Main, YC’s first building of size. It was the centerpiece of the original campus, a grand old pile of bricks, towering up on East Hill, rising 110 feet from its foundations to the tip of its flagpole, a 45-star national emblem waving in a stiff Nebraska breeze above the grassy plains of the early 1890s. It stood as a monument to the possible, a symbol for humans whose reach exceeds their grasp.

In 1870, York was little more than one lone house. Less than a decade had passed since the passage of the Homestead Act and the Transcontinental Railroad had just been completed the previous year. The railroad reached York in 1878, and the town sprang to life. Over the intervening dozen years, progress was planted on the plains. Beyond a bank, a post office, dry goods stores, and a newspaper, a school was envisioned. In 1880, the Methodists opened theirs—the Nebraska Conference Seminary—with their literature describing their school as located in a “thrifty section of the state, in a town where there never had been a saloon.” They set up shop in January in the original Congregational Academy building located on the west end of Seventh Street. (While the building is gone today, Academy Avenue remains.)

The school did well for a time, moving to a new brick facility located close to the site of today’s St. Joseph’s Catholic Church. (The building—now gone—would later house the Ursuline Sisters, an order of nuns, and even later still would become St. Joseph’s Academy.) The seminary became a college in 1883 and was officially renamed Methodist Episcopal College of Nebraska, but often the locals just simply referred to the school as if it were theirs—as York College. The college boasted a dozen instructors and had an enrollment of 313 by 1885. Tuition ran between $6 and $7 per term. Many of the college’s students focused their studies on teacher education and business courses. But even as enrollment climbed, so did debts, and by 1888, the Methodists closed the doors, with the Catholic Church taking over and reopening the facility the following year as Ursuline Academy. Meanwhile, the Methodists moved to Lincoln and opened a new school—Nebraska Wesleyan University.

With its first “college” having come and gone within a single decade, the people of York sought out another religious group to establish a college in their prairie community. Land was selected for a college by local citizens on York’s East Hill. Then, enter the United Brethren. In 1886, the UB Church had purchased, from a group of Baptists, Gibbon Collegiate Institute, located in Gibbon, NE, about 70 miles east of York. The academy there ran from 1886 until 1890, “under the auspices of Western College, in Toledo, IA.” But Gibbon proved an awkward place for a college. The town was too small, and local citizens never fully bought in. Financial problems were exaggerated by a severe drought that hit the region. Church officials decided to close the Gibbon school and move their operations to York, once the Methodists had packed up and left. When the UB opened their new school, they named it York College. Ironically, the UB Congregation in York had been established just three years earlier.

It is from this time-distant place—York, Nebraska, 1890— that our story begins to take on a life of its own, one, ultimately, of endurance; one that has seen fitful starts and stops; financial crises and historical drama; problems and praises. Over the next 132 years, York College would not only endure but would thrive, progress, spread out, even as those offering its classes, raising its buildings, and guiding six generations of young men and women would themselves change, with each new generation of instructors, administrators, staff, students, alumni and various and sundry well-wishers. The story of York College is, in some respects, two stories linked in purpose and place. The United Brethren laid the groundwork for the college on the hill with 11 presidents steering the ship for more than 60 years. Those stalwart men of faith,

(left) Classes in 1890-91 were held on the second floor of the structure where three men in white shirts are standing, the site of Cobbs Dry Goods, in the Wirt Building located on the west side of the town square.

(right) A 1902 newspaper ad showcasing Old Main concludes: "Send for full information and be convinced that the advantages are the best, the rates the lowest, the results the most satisfactory, at York College, the People's School."

(below) As the 1920s opened, three buildings comprised nearly the entire campus of York College, including Hulitt Conservatory of Music, the YC Gymnasium (later to become McGeHee Hall), and the Administration Building (Old Main).

relying on push and enterprise, built a school from scratch, and their efforts continue to bear fruit. To leave its leaders anonymous and unnamed would be amiss:

United Brethren Presidents of York College, 1890-1956: 1890-1894 Rev. J. George 1894-1897 W. S. Reese 1897-1913 Rev. W. E. Schell 1913-1919 Rev. M. O. McLaughlin 1919-1921 Dr. H. U. Roop 1921-1924 Dr. W. O. Jones 1924-1928 Rev. E. W. Emery 1928-1938 Rev. J. R. Overmiller 1938-1947 Dr. D. E. Weidler 1947-1953 Dr. Walter E. Bachman 1953-1956 Dr. A. V. Howland

Those early decades brought new buildings, a wide variety of courses and academic programs, and sports teams. There were dramatic productions and literary societies and music. And traditions, some of which have remained a part of campus to today. The college’s first song, a theme written by C. W. Gwinn in 1905 (and later tweaked by Miss Ethel Clarke) opens with confident lyrics: “Come, let us sing together / A glad Triumphant song / To our own Alma Mater / With praises loud and long / The pansy is her emblem / Of every tint and hue / Her banner floating o’er us / Is the royal White and Blue.” Today, both the pansy

continued next page

and the song are no longer a part of York College, but another song, one penned by Ruby Carol Rickard, remains as the college anthem, ever extolling loyalty for the same blue and white of York College’s first theme’s earlier lyrics: “In our hearts will ever ever be / Blue and White, a blessed memory / Through the years our voices raised / In praise to thee, / All hail, York, hail.”

Then, at the mid-point of the 20th century, a redirection for York College. Venerable Old Main burned, leaving among its ashes the dreams of the United Brethren. The fire began in an upper portion of the building’s west side, perhaps due to some faulty wiring. The January 3rd fire occurred on a freezing night, and firefighters were plagued by low water pressure. After the fire, residents of York gave assistance, including York Public Schools and St. Joseph’s School. The president of Hastings College offered the loan of a number of classroom chairs. The York Daily NewsTimes reported the story with the following lead on January 4: “The fire charred skeleton of the York College Administration Building today stood in evidence of a scorching conflagration which last night destroyed the nerve center of the Evangelical United Brethren school.”

School administrators decided to continue classes, despite the loss of classrooms and the chemistry lab, within one day of the fire. As one administrator said, “We are only collecting our bearings and preparing to make a bigger and better than ever before York College.” But for all the brave faces, the loss of Old Main proved fatal for the Evangelical United Brethren’s college in York. The college remained open through the academic year and continued for three more years before the EUB finally closed its doors in York and moved everything to its Westmar, Iowa, campus.

Between 1954 and 1956, the York College campus stood, but with college classes no longer being offered. The buildings were still there, but the heart of York College was gone. The weedinfested foundations of Old Main remained a mocking reminder of what had been.

The closing of YC in 1954 was headline news in Nebraska. Early that year, three Nebraska Church of Christ ministers— Hershel Dyer, Donald Michael, and Dale Larsen—began dreaming, discussing the possibilities of the church taking over the abandoned campus. In May, during a car ride together on Highway 81, Larsen and Dyer stopped at the York Co-Op Oil Company, dropped a dime to the local Chamber of Commerce and asked a stranger with whom they should speak about the former United Brethren college. They were told to talk with York banker E. A. Levitt. In June, 14 Church of Christ members met with town officials around park tables north of the York Post Office. Many meetings later, a new board of trustees was selected and, by May 1956, YC was revived as a Church of Christ-affiliated college. Harvey Childress became president. A second faith-based school reopened the old doors of buildings on East Hill and, with a second wind, began offering classes, playing sports, building new facilities, and recreating a new Christian institution of higher learning, one that has endured, built on the legacy of the past, standing on the shoulders of those who had come before them. Ten men have led this resuscitated version of YC:

Church of Christ Presidents of York College, 1955-2022: 1955-1957* Harvey A. Childress 1957-1960 Gene Hancock, Jr. 1960-1978 Dr. Dale R. Larsen 1978-1987 Dr. Gary R. Bartholomew 1987-1991 Dr. Don E. Gardner 1991-1995 Dr. C. Larry Roberts 1995-1996 Dr. Garrett E. Baker 1996-2009 Dr. R. Wayne Baker 2009-2020 Dr. Steve W. Eckman 2020- Dr. Samuel A. Smith

When I came to York College as a student in 1971—my father was friends with Dale Larsen who had become president in 1960, so dad thought YC was the place for me—the campus was still ever so small, a tidy academic world consisting of Hulitt Hall,

(top) The charred remains of the Administration Building gives pause to students as they consider the College's future.

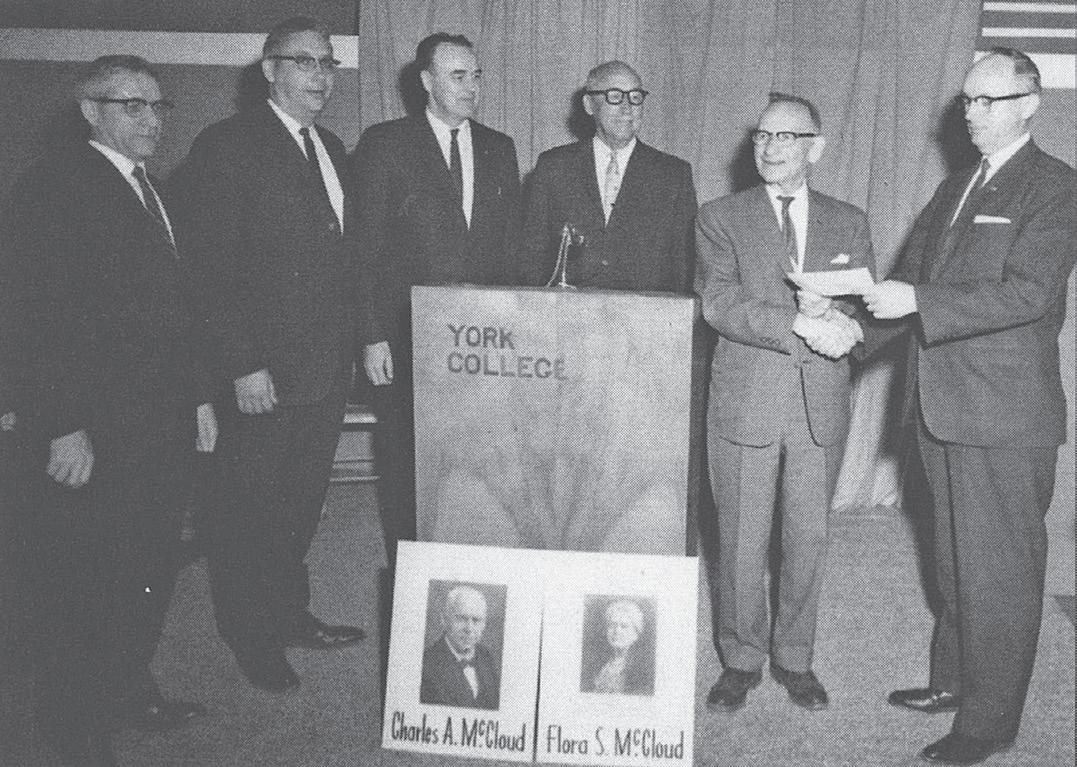

(above) Ten years after closing its doors, on May 5, 1964, the College celebrated with the York community a $50,000 bequest from Charles McCloud to build a new dormitory. Pictured from left to right are Walter Kupke, Robert Johns, Larry Lane, and R.A. Freeman watching President Larsen receiving the check from E. A. Levitt. Ground breaking had occured the year before, and McCloud Hall was dedicated on October 9, 1964. In light of this ongoing support, the 1965 Crusader was dedicated to the City of York.

Middlebrook, McGehee, McCloud, Gurganus, the newly-opened Levitt Library, a scattering of Quonset huts, and some creaky old houses that featured bedrooms-turned-into-office-space. Two rock throws in any direction pretty much spanned the campus. I came to the college along with Beverly Doty, a girl I would marry the following year. When we left in 1973, we had no concept of returning 20 years later to teach as professors of English and history. We’ve been here 30 years now. Bev has retired, and I will sooner than later.

Thirty years have slipped by quickly, and the campus has changed dramatically. During our time here, YC has gained Sack Hall, the Holthus Field House, the Campbell Center, the Bartholomew Center for Performing Arts, the apartments, buildings that have expanded our campus and extended our mission. We were here on a cold day in December 1999 when the old St. Paul’s Evangelical Lutheran Church building was moved the seven miles from campus along snowy rural roads to take its place, after extensive renovations, as the Prayer Chapel, its doors finally opening in 2004. We were here the day the Mackey Center’s clock tower, its bright copper shining in the sun, was craned into place, capping a new campus icon. For years our offices were in the venerable, old Hulitt Hall, which has now experienced such a dramatic facelift it would hardly be recognizable to its closest friend. But our story is only part of that larger YC story, with its cast of tens of thousands.

Now, the book is closing on York College, and a new chapter opening on York University. What does the future hold for YU? Your guess is as good as mine. But if it’s anything like the past, there will be high points and struggles. As we move into that new future, let’s make sure we don’t lose sight of our past. Those days of the United Brethren followed by those of the Churches of Christ have worked hand in hand to get us where we are today. Each of those stories, when played with both hands on the keys, have provided both a melody and a rhythm, a song that keeps rewriting itself. n

(above) Dr. Tim McNeese ’73 led two different classes of HST 397 students in unearthing the 110 year-old site of Old Main in 1999 and 2000. McNeese commented, "It gives you a different kind of feeling to stand on a floor where no one has walked in nearly 50 years."

(right) McNeese is one of the longest tenured faculty at York College, teaching history since 1992. He chairs the department of history and serves as an elder at the East Hill Church of Christ. He and Bev will celebrate their 49th anniversary this summer and have 2 grown children and 6 grandchildren.

McNeese Publishes New Book

Dr. Tim McNeese’s new book includes something old and something new. Titled Time in the Wilderness: The Formative Years of John “Black Jack” Pershing in the American West, the biography was released in December through the University of Nebraska Press’s Potomac Books imprint. The book covers the first full-length biography of General Pershing’s life published in more than forty years, but with one purposeful limitation. McNeese focuses on Pershing’s military service, not in the European theater during the Great War, but rather on the thirty years he spent as a cavalry officer prior to the war, years the history professor considers crucial in forming Pershing into the commander he would one day need to become to lead two million men in European combat, the largest number of U.S. servicemen in uniform to that date.

“I cut off my study short of Pershing’s World War I experiences for a reason,” says McNeese. “There are dozens of books that focus on Pershing during the war. That is a base completely covered. But there are few books that deal with the years he spent as a young cavalry officer in the American West, and I believe those years represent a crucial cauldron of preparation for Pershing.”

“Publishing something of this length and level can take a long time to turn around” says McNeese. “If you’re an impatient person, writing and publishing may not be for you.”

The result is a 400+ page book, the longest McNeese has written, one spanning Pershing’s life from his birth through his leadership of the Punitive Expedition against the Mexican pistolero Pancho Villa in 1916. McNeese’s new book can be found on Amazon and Barnes and Noble websites as well as through the Potomac Books website. He has written more than 130 books over the years and appeared on television programs on the History Channel, the American Heroes Channel, and Discovery’s CuriosityStream.

The YC professor has already completed his next book which is now in process of publication. This work is being published by Two Dot Books, an imprint of Rowman & Littlefield and focuses on another American figure whose story is largely unknown. Titled William Henry Jackson’s Lens: How Yellowstone’s Famous Photographer Captured the American West, the book is a biography of the nineteenth century photographer who took the first photos of several places in the American West, including Yellowstone, the Tetons, Mesa Verde, Chaco Canyon, and Colorado’s Mount of the Holy Cross. The book is slated for publication in late 2022 or early 2023.