What we know about nature and wildlife in Yorkshire State

What we know about nature and wildlife in Yorkshire State

This State of Yorkshire’s Nature work was made possible by the generous gift of the Joyce Mary Mountain Will Trust

Joyce Mary Mountain loved Yorkshire and its wildlife. Growing up near Shipley in the 1930s, she spent her childhood near Baildon Moor. She had a great interest in both the countryside and wildlife, and was keen to support nature projects in her home county. Yorkshire Wildlife Trust are honoured to receive a gift from the Joyce Mary Mountain Will Trust which has helped us undertake this important work and drive forward Yorkshire’s wildlife recovery. Through this gift Joyce’s love of wildlife lives on and, because of her generosity and consideration, we will be better able to tackle the climate and ecological crises that faces all of us.

The most important thing to do in a crisis is first identify the problem, and then seek solutions. The natural world is currently facing two interlinked crises – the climate emergency and the biodiversity crisis. It is easy for an individual or an organisation to feel helpless to do anything about either of them. But we can, and we must.And the best place to start is at home, here in Yorkshire.

The State of Yorkshire’s Nature seeks to identify what is happening to the

plants and animals with which we share God’s own county. And then, where we have identified the main threats to our wildlife, suggest solutions that heal and restore the natural world. As far as I am aware the project is unique in the depth and breadth of its analyses of regional data. It tells us what is actually happening – and needed – in Yorkshire. Many of the solutions – for example, restoring moorland peat bogs or creating new woodland – are also part of the solution to the climate emergency because they draw down carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and lock it away.

Rachael Bice Chief Executive, Yorkshire Wildlife Trust

The crisis for nature is real, and it is urgent. We are beyond the point where nature can heal itself. The actions humans take to restore the more-thanhuman world within the next decade are crucial, and ensuring they are targeted to have optimum impact is essential when time and resources are finite.

Our report provides clear evidence about the abundance and distribution of the precious species which make up the remarkable biodiversity of Yorkshire. It marks an important moment in the quest to bend the curve on nature’s decline to a trajectory of recovery.

Yorkshire Wildlife Trust was established nearly 80 years ago to provide protection and voice to the wildlife and wild places across the county. This report shows our work has never been more necessary or urgent since naturalists, scientists and passionate environmentalists first gathered to care for our wildlife, woven throughout our communities, in the name of the Trust.

As we look ahead, the insights from this report will provide the framework for our actions and structure the approach we take to monitoring our impact.

We thank everyone who has contributed to the report and the data

They may look like small steps, but all long journeys must start somewhere – and like all journeys, it will take time and effort.

But I hope this report will convince you that we can do something: we must do something, and in so doing we will make more space for nature, to benefit and protect the people and the wildlife of this wonderful county.

“This report will convince you that we can do something: we must do something”

on which it has drawn, reflecting the amazing dedication and expertise of our biological recording community who quietly seek and observe the creatures and plants which emerge and depart from view, season on season.

Finally, thanks go to the Joyce Mary Mountain Will Trust whose generous support has enabled this research to be done and consequent crucial next steps to be identified.

“This report shows our work has never been more necessary or urgent”

This report is based on new analyses of the distribution and abundance of Yorkshire’s biodiversity, and the extent and condition of our wildlife habitats –terrestrial, marine and freshwater. It provides an evidence-based assessment of the state of Yorkshire’s nature, a foundation on which to collate further data, and a baseline to measure the success of nature recovery work and actions.

Yorkshire hosts around twothirds of all British nonmicrobial species – that’s over 40,000 species.

Over 200 of our plant, bird, butterfly and moth species are of national conservation concern.

Yorkshire has Nationally Rare habitats including more than half of the country’s limestone pavement and upland calcareous grassland.

stronghold for around 3,000 species, making us important custodians.

Coastal habitats Rare habitats

The Humber Estuary is one of Britain’s most important inshore habitats. The Flamborough and Filey coast support the largest breeding sea-bird colony on the British mainland.

Yorkshire has the most northerly chalk streams in the world – an Internationally Rare habitat.

Nearly 2,000 species may have disappeared from Yorkshire over the last 200 years. A further 3,000 are at risk of extinction.

Species continue to decline – nearly 1 in 5 species have declined by more than 25% in the last 20-30 years.

Biodiversity is diminishing – common species are increasing while rare species are disappearing.

Yorkshire’s terrestrial wildlife sites and protected areas are too few, too small and too scattered – 15% of the county – to form a healthy and resilient ecological network.

Only 1 in 10 terrestrial wildlife sites have legal protection.

Less than 20% of both protected sites and rivers are in a healthy state.

Ecological functions are diminished – less than 20% of Yorkshire’s peatlands remain undamaged, resulting in the loss of keystone species such as Sphagnum mosses.

Yorkshire needs a wider network of high quality and connected marine, terrestrial and freshwater sites, big enough to sustain the ecological and physical processes required to support thriving populations of species.

3. Our goal is a nature network across Yorkshire with a broad range of habitats

A minimum of 30% of positively managed land and sea is required to create a thriving multi-functional landscape.

Each of Yorkshire’s 40,000+ species of plants, animals and fungi has its own ecological niche and distinct habitat preferences. We need to sustain and expand their full range of habitats.

4. Water and limestone are significant domains, and provide key opportunities for nature’s recovery

Wet habitats favour biodiversity but much of Yorkshire has been drained, resulting in the loss of many species. Threatened species are now often associated with wet habitats, so creating more wet habitats will promote biodiversity.

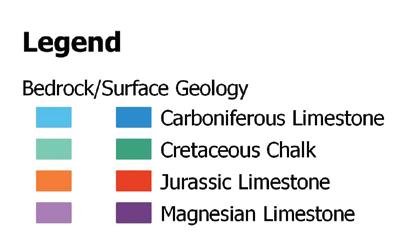

Limestone habitats are especially rich. Yorkshire is unique in having four different types of limestone, which are home to many of our rarest and most threatened plants. As a result, we need to enhance the range of habitats in those areas.

Nearly three-quarters of Yorkshire is farmland

A balance is needed between working to benefit wildlife, and supporting farmers to work without impacting food production and income.

Towns and cities have enormous potential for wildlife

10% of Yorkshire is urban –which is where most people will engage with nature.

National Parks and National Landscapes account for almost one third of Yorkshire

The size and diversity of these habitats provide significant opportunity to contribute to nature’s recovery.

Healthy coasts and seas require land, freshwater and marine habitats to be well-managed

Yorkshire’s coastal zone is a complex inter-connected network of marine and terrestrial habitats, species and processes.

The State of Yorkshire’s Nature has drawn on a unique body of evidence about Yorkshire’s species, habitats, and ecosystems. The report reveals alarming trends, but also shows what can be done to halt and reverse decline, and provides a baseline from which to monitor progress toward recovery goals.

A changing Yorkshire

Yorkshire’s dramatic coastlines, seas and stunning landscapes are undoubtedly beautiful and still rich in wildlife, but they are transforming from land-use pressures and a changing climate. Some changes may be obvious; the drainage of a local wetland, the loss of woodland to a new road, the dredging and pollution of a river once rich in wildlife, or just fewer insects. Strategies that will protect and enhance nature in Yorkshire need robust evidence that shows what is happening, and this report provides that evidence.

This State of Yorkshire’s Nature report establishes a baseline for understanding how nature is faring in Yorkshire. It brings together the best available data, providing an assessment of the current state of Yorkshire’s environment. Even though we don’t have data on all species and habitats, we believe that the conclusions are robust.

As more information becomes available, we will build on this platform.

This report was compiled by Yorkshire Wildlife Trust in association with our partners: Yorkshire Naturalists’ Union, British Trust for Ornithology, Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland, Butterfly Conservation. The Trust is grateful for the support received from a wealth of local organisations, experts, county recorders, and volunteers who provided data, written content, and peer review on the analyses.

Recognising long-term changes to the environment is important – the shifting baseline syndrome

Understanding the starting point or baseline is an important concept in conservation and ecology. Our perception of the state of nature where we live is typically set in our childhood – so each new generation accepts the situation in which they were raised as ‘normal’.

However, each generation historically has left the state of nature slightly worse for the next. As a result, younger generations accept an

environment that would seem degraded to their parents, and even more so to their grandparents.

This loss of knowledge about the state of the natural world over time is referred to as shifting baseline syndrome. It is important to understand because essential parts of the natural world are not only lost but also forgotten.

If we are unable to recognise what we are losing, there is a risk that we won’t comprehend the destruction of the natural world around us. This will reduce our ambitions and, crucially, mean we fail to take action to remedy the situation.

You

can’t manage what you don’t know

To understand how nature is faring across the UK, a State of Nature report has been produced every few years since 2013. These reports bring together data and expertise to identify overall change in abundance and distribution for a range of species. Sadly, they highlight continuing declines.

Many counties and regions have used the national data to better understand the state of their nature locally. This State of Yorkshire’s Nature report shares this ambition, whilst also using data specific to Yorkshire. This approach provides an accurate understanding of the changes happening to nature in Yorkshire, allows us to discover how diverse and abundant our wildlife is, and whether it is increasing or declining.

For this report, the data needs to be comparable across the county and over time, and to be available for a large enough set of species so that patterns can show up. The analyses focus on the four groups (birds, plants, mammals and lepidoptera- butterflies and moths) that meet these criteria. The evidence base for this analysis is briefly summarised here but will be published in full in the Yorkshire Naturalists’ Union journal The Naturalist, and on the Yorkshire Wildlife Trust website.

To restore nature in Yorkshire, we must first protect and enhance existing habitats and then expand those across the county. This is the basis of the global “30 by 30” target to protect 30% of land and sea by 2030 – which the UK has formally committed to in order to reverse the decline of nature nationally. By analysing what is happening to well-documented species of plants and animals, this report identifies the habitats that are most important for nature’s recovery, including the state of terrestrial, freshwater and marine ecosystems, and explores the coherence and resilience of the protected area network in Yorkshire.

It will be important to implement adequate monitoring as we work towards nature recovery goals across Yorkshire, to understand if the actions undertaken are sufficient and effective.

A key principle of monitoring is choosing the simplest indicator that meets the need. This is particularly important for ensuring resourcing (survey skills, time and funding) is available to sustain long-term monitoring over sufficient periods.

The Yorkshire Species of Concern lists produced as part of this report provide a useful monitoring tool, as they are

“To restore nature in Yorkshire, we must first protect and enhance existing habitats and then expand those across the county.”

Other groups have not been forgotten. but a full analysis for groups such as fungi, dragonflies and reptiles is not yet possible. Their conservation is still vital, and reference to these groups has been made based on the best available data.

generated from data that has been collected by multiple volunteer surveyors (public, naturalists, organisations) and is likely to continue to be collected and available in future, making it possible to measure change against this baseline.

If nature recovery actions are successful, there should be fewer species on the Yorkshire Species of Concern lists in future, and those species with high index values should come to have lower values as they recover or their abundance increases. How well they are doing across Yorkshire as a whole will be a measure of habitat status and ecosystem health at landscape scale.

Yorkshire Stronghold Species are species that have a disproportionate fraction of their British ( ≥14%) and/or English (≥24%) distribution in Yorkshire, making them of particular significance. Yorkshire is 7% of Britain and 12% of England: above these thresholds, Yorkshire Stronghold Species are at least twice as likely to be found in Yorkshire as their national distribution predicts.

An Index of Yorkshire Species of Concern was created, based on (i) national threat status, (ii) rarity in Yorkshire, (iii) the extent of their decline in Yorkshire, and (iv) their Yorkshire stronghold status.

The index has been used to:

Identify species of key conservation concern.

Understand current changes to Yorkshire’s biodiversity.

Define habitats favoured by such species and measure the degree of protection offered by the protected area network.

Measure the success of conservation actions and policies.

191 species either breed in Yorkshire or are regular winter visitors. That’s two-thirds of British regular breeding and wintering species. Many other species are rare visitors or vagrants – these have not been considered.

Many Yorkshire birds are under threat: Two-thirds of Yorkshire’s regular breeding and wintering bird species are either red or amber-listed nationally.

Yorkshire’s bird populations matter: A quarter of species are Yorkshire Stronghold Species, meaning Yorkshire holds a significant proportion of the national population. More than a third of the British breeding distribution of both Tree Sparrow and Pochard is in Yorkshire.

Yorkshire’s bird fauna is in a state of flux: The range of 90% of Yorkshire’s birds has changed in the last 30 years. Many species have colonised or re-colonised Yorkshire recently, including Spoonbill, Bittern and Crane.

Rare species are faring badly: Following national trends, more bird species are increasing in Yorkshire (e.g. Buzzard) than are declining (e.g. Spotted Flycatcher). However, species that are declining are rarer nationally than increasing species and so, alarmingly, bird biodiversity is declining.

Wetland habitats are important for birds:

Species with high values of conservation concern are often wetland species, although coasts, uplands and woods are also important. Wetlands also host many of the species that have recently colonised the county.

Swifts breed in urban environments

Willow Tit

UK’s most threatened resident bird species

Some species are of high conservation concern: We can identify species of conservation concern in Yorkshire using data on abundance, range and dynamics. Among breeding species, Willow Tit and Tree Sparrow stand out. Ring Ouzel is an important summer visitor.

Yorkshire Stronghold Species

Significant population decrease in the county which may be accelerating

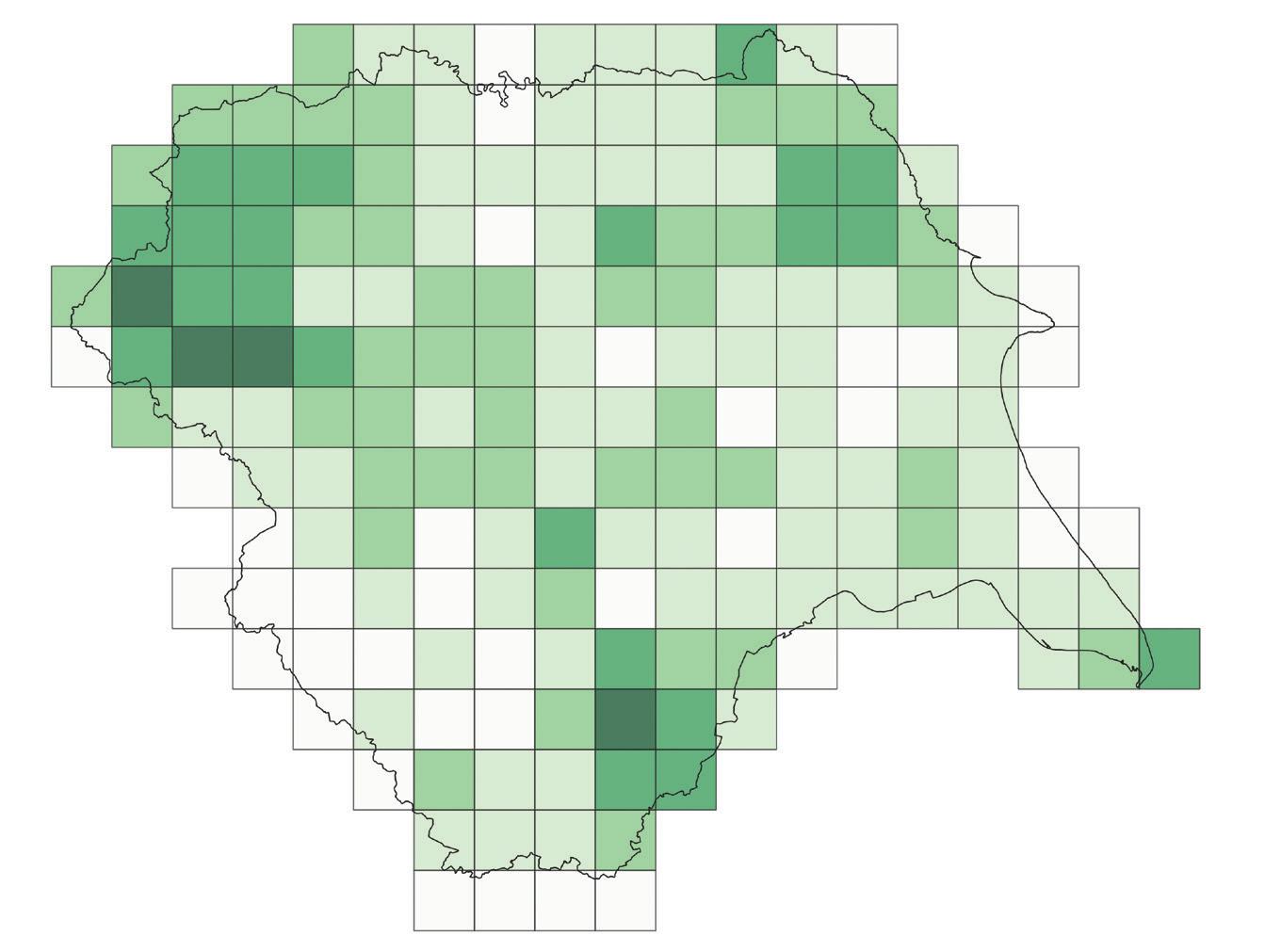

Nearly 1,000 species of native flowering plants and ferns are currently known in Yorkshire – about two-thirds of the total native vascular plant flora of Britain. Our flora includes 96 species that are nationally Rare or Scarce.

Yorkshire’s flora is nationally significant:

There are 64 ‘Stronghold’ species – those that have a large proportion of their national distribution within Yorkshire, giving us a particular responsibility for these species.

Our flora is threatened: 9% of Yorkshire plant species are regarded as Threatened at the national scale.

Another 44 species are locally Extinct and 17 have not been recorded in Yorkshire in the period since 1970. Nearly half of the species that have been lost from Yorkshire were plants of wet habitats.

The flora is in a state of flux:

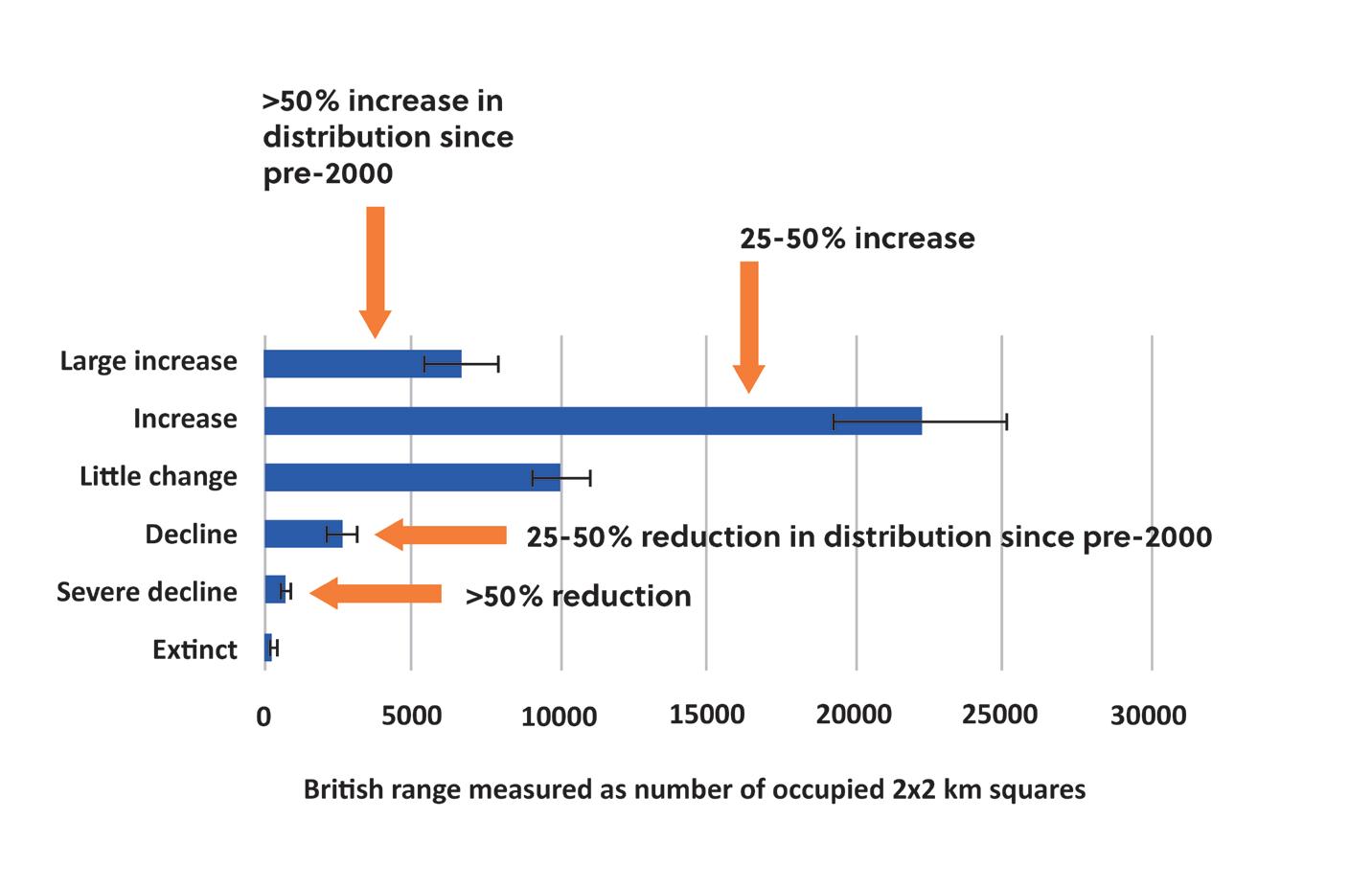

A quarter of Yorkshire’s plants have declined in distribution by at least 25% since 2000, and nearly 10% have declined by more than half. However, a similar proportion have increased their distribution to an equivalent extent

within the county. The species that are declining are much rarer nationally than increasing species: these large-scale changes are therefore reducing the conservation value of the Yorkshire flora.

The plant list of Yorkshire Species of Concern:

Well-known rarities such as Lady’s Slipper Orchid, English Sandwort and a further 120 species are regarded as of key conservation concern. Where conservation activity is species-focused –i.e. aimed at bolstering particular species – the Yorkshire Species of Concern list will be used to prioritise them.

Only British populations are in Yorkshire

Declined by 48% in Yorkshire

Not all habitats are equal: Yorkshire Species of Concern are disproportionately found on limestone and in wet habitats, with limestone grasslands, fens and open water habitats being among the most important.

Endangered in Britain

Water Germander

Nationally Endangered

Extinct in Yorkshire

Re-introduced at Bolton-onSwale, a Yorkshire Wildlife Trust reserve

Yorkshire is home to two-thirds of British butterflies (40 species) and larger (macro) moths (662 species), but we know much less about the smaller (micro) moths that have only recently been widely studied. There are around 1,100 micro moth species on the Yorkshire list.

Many of Yorkshire’s butterflies are threatened nationally: 30% of Yorkshire’s butterflies are threatened with extinction, including Duke of Burgundy and Pearl-bordered Fritillary, for which Yorkshire holds important populations.

Many moths have stronghold populations in Yorkshire:

Species like Dark Bordered Beauty and Scarce Vapourer have a large part of their national distribution in the county. Several moths are at the southern edge of their range here and are vulnerable to climate change: they have already been observed to be retreating uphill.

The Lepidoptera fauna of Yorkshire is changing fast:

130 moth species have not been seen since prior to 2000, whilst 185 new species have arrived in the county. Some declines have been very steep: Spinach and Lackey have both declined by over 4% per year in the last 20 years and may disappear from the county.

Rare species are losing, common ones are winning:

Overall, the number of moth and butterfly species may be increasing but declining species are more likely to be Nationally Rare, and our fauna is becoming less distinctive.

Woodlands are a key habitat: Moth species of greatest conservation concern are most frequent in woodland – especially wet woodland – although heaths, moors, and wet habitats such as fens are also important.

Conservation works:

Remarkably, although no Yorkshire Wildlife Trust nature reserves were established with butterflies and moths in mind, those reserves provide a high degree of protection to Yorkshire Species of Concern. This shows that conserving habitats can conserve species.

Only England locality

Population declining

Species are on the move:

Butterflies such as Essex Skipper and moths such as the spectacular Clifden Nonpareil are moving north and are now well-established in Yorkshire. The iconic Purple Emperor appeared in Yorkshire for the first time in at least 80 years in 2022.

In contrast, northern species such as the Large Heath Butterfly and the Lunar Thorn Moth are faring badly in lowland habitats; Lunar Thorn appears to have retreated into the hills at an altitudinal rate of 5m per year.

Re-introduction programme in Scotland

Clifden Nonpareil

Natural and rapid expansion into Yorkshire

Needs wet woodland habitats

Pearl-bordered Fritillary

Nationally Vulnerable

Rarest butterfly in Yorkshire

Yorkshire is home to 32 native terrestrial mammal species, 5 amphibians and 4 reptiles. These include several Species of Conservation Concern, such as Red Squirrel, Water Vole, Mountain Hare, Hazel Dormouse and Adder. These species represent 70% of the British total.

Yorkshire’s mammals are at risk – 2 are already Extinct, 4 are Threatened nationally, and 6 are declining. Almost a third of terrestrial mammals in Yorkshire are Species of Concern.

Mammals are often keystone species, with major impacts on habitats. Rabbit – an introduced species – has historically been important in maintaining short turf grasslands. Recent declines could impact management of grasslands on fragile habitats such as on chalk grasslands and heaths. Deer can prevent regeneration in woodlands, whereas Beaver can re-wet catchments and greatly enhance flood storage ability.

mammals as Species of Principal Importance in England – Sei Whale is Endangered and Fin Whale and Sperm

Water Vole

Invasive mammals are a serious problem: American Mink, originally established by escapees from fur farms, are now ubiquitous and are the cause of the catastrophic decline of Water Vole populations.

Mammals need complex ecosystems: Mammals are very mobile and tend to use multiple habitats or habitat edges. They thrive best in ecosystems where many habitats occur, and their single largest habitat preference is woodland.

Since 2000, 13 marine mammal species have been recorded: These represent about 41% of the marine mammals that occur around the British Isles. Three are regarded as Threatened globally under the IUCN definitions, which list 12 UK marine

Red Squirrel

Nationally Endangered

69% decline in Yorkshire

Threatened by invasive Grey Squirrel

Adder

Nationally Vulnerable

Threatened by public pressure, habitat loss and management change

Nationally Endangered

41% decline in Yorkshire

Threatened by invasive American Mink

We know too little about most other groups

Despite their critical importance as grazers (molluscs), pollinators (bees and hoverflies), predators (wasps and beetles), parasites (ichneumon and fungi), or decomposers (beetles and fungi), more data is needed. This lack of knowledge reflects the small numbers of naturalists with the right expertise – a deficiency that needs urgent attention.

Nature recovery in Yorkshire will benefit biodiversity nationally

Yorkshire hosts over two-thirds of British species in most groups of plants and animals. There are thought to be 70,000 non-microbial species in Britain, so with over two-thirds of those, Yorkshire is thought to be home to between 40,000 and 50,000 species. The figure is high because of Yorkshire’s size (7% of Britain’s and 12% of England’s land area), geology, and environmental diversity.

The Yorkshire list of dragonflies and damselflies comprises 25 species, representing 54% of the 46 species on the British list. Only 1 species has been lost from the county

The list of fungi, including lichens, comprises around 6,500 species. This represents 43% of British fungi and is almost certainly an underestimate due to lack of recorders

Yorkshire has a few sites which are internationally significant for the range of fungi present

Yorkshire hosts over two-thirds of British species in most groups of plants and animals

3 species widespread in Yorkshire may be declining nationally – Black Darter, Common Hawker and Emerald Damselfly. The last two of these are found especially in acid bog pools, emphasising that sustaining specific wet habitats is of high conservation importance

Over 200 plant, bird, butterfly and moth species in Yorkshire are of National Conservation Concern: Many of these are protected by national legislation.

Yorkshire is a stronghold for many species: We identified Yorkshire Stronghold Species – those that have a particularly large part of their national population or range in Yorkshire. For the best-studied groups of birds, plants and moths, we found over 130 Yorkshire Stronghold Species. Extrapolating to other groups, there may be 3,000 Stronghold Species in Yorkshire, for which we have a particular conservation responsibility.

Yorkshire is also a stronghold for important habitats: More than half of Britain’s limestone pavement and upland calcareous grassland is found here, and blanket bog and lowland raised bog are also strongly represented in Yorkshire. Another Internationally Rare wet habitat is chalk streams: those in Yorkshire are the most northerly in the world.

The rich biodiversity of Yorkshire shows what we can achieve by allowing nature to recover here.

430 species of spider have been recorded from Yorkshire representing 65% of British spiders

8 are important species in terms of their nature conservation status

Larinioides patagiatus (Araneidae)

Critically Endangered Caddisfly

Only British population is in Yorkshire (Malham Tarn)

727 species of mosses and liverworts (67% of British bryophytes) have been recorded in Yorkshire, of which 77 are now extinct

Mosses and liverworts as a group depend on wet habitats

White-clawed Crayfish require clean, calcareous streams, rivers and lakes

They are threatened by the invasive American Signal Crayfish, which carry crayfish plague

54% of British grasshopper and cricket species have been recorded in Yorkshire: several have only recently arrived

The magnesian limestone belt, running north-south through Yorkshire, facilitates the northwards migration of many invertebrates

The state of flux in Yorkshire’s biodiversity is a cause for serious concern. Whilst as many species are increasing as are declining in Yorkshire, the species that are disappearing are rarer nationally than the increasing species. The result will be a duller natural world, full of common species that are found everywhere and with fewer of the scarcer ones that make Yorkshire special.

Yorkshire’s fauna and flora have suffered losses: Extinctions in littlestudied groups will have gone unnoticed, but 1 in 20 of Yorkshire’s plants and moths have been lost. Across all groups, the rate of loss is 4% or around 2,000 species over the last 200 years.

Many plants and animals are becoming rarer in Yorkshire: 27% of plants and 16% of breeding bird species are declining. Across all groups examined, 18% of species are declining.

Declining species are at risk of extinction: Many declines are severe, with some approaching 100%. We may be on the verge of a new wave of extinction: 3% of Yorkshire’s plants now grow in just one place.

But many species are colonising or increasing: 11% of moths and 4% of species overall are recent arrivals in Yorkshire.

Declining plant species (3 lower bars) are much rarer nationally than increasing species (top 2 bars). The relative scarcity of the species showing greatest expansion is unsurprising – if they’re already widespread they can’t expand! The same is true of birds and moths.

Increasing species are common species: More species (21%) are increasing than are declining (18%), but the declining species are, on average, rarer nationally than the increasing species.

“Whilst as many species are increasing as are declining in Yorkshire, the species that are disappearing are rarer nationally than the increasing species.”

Generalist species benefit from human activity: Intensive agriculture, river pollution, urban sprawl, and climate change all reduce or damage the more natural habitats on which rare and specialist species depend.

Across all groups examined in Yorkshire:

The rate of species loss is 4%

18 % of species are declining

4% of overall species are recent arrivals

Three main factors promote colonisation by new species: direct assistance, habitat change, and climate change.

Some species need (or are given) a helping hand. The Red Kite is now common in Yorkshire because it was deliberately re-introduced. Several butterflies that went extinct here, such as Scotch Argus, now have thriving colonies after unofficial reintroductions.

The creation of habitat can attract new species, particularly water birds such as Spoonbill and Avocet. Former gravel pits and wetlands created by mining subsidence now make superb nature reserves with a good range of habitats.

Some new arrivals become serious problems. Himalayan Balsam, American Mink and Signal Crayfish are species that have displaced existing flora and fauna: Mink is thought to be the main cause of Water Vole decline. Invasive species can be native too: Nettles are increasing rapidly in Yorkshire thanks to disturbance and atmospheric nitrogen pollution. New diseases also arrive all the time and some can be devastating; Ash dieback, caused by an accidentally-introduced fungus, is likely to lead to the loss of most of our Ash trees, the most important upland tree in Yorkshire.

Little Egret and Cetti’s Warbler have both extended their range north into Yorkshire in recent years. 50 years ago they would have had birdwatchers in paroxysms of delight, but now they are almost commonplace.

Whilst climate change brings new species, we will also lose species as the climate warms. The arctic-alpine flora of Yorkshire is at obvious risk. Dwarf Cornel survives on steep north-facing slopes in a single locality in the North York Moors. It would be surprising if it was still there in 50 years’ time.

From coast to the subalpine, with complex geology – including large areas of four different types of limestone – and major rivers, Yorkshire is very diverse.

Nationally important ‘priority habitats’ make up 20% of Yorkshire but much of it is in poor condition and not managed for wildlife: Six of these are Yorkshire Stronghold habitats, where Yorkshire holds a disproportionate amount of the UK total.

More than half of the country’s limestone pavement and upland calcareous grassland habitats are found in Yorkshire.

Almost a third of country’s blanket bog, upland heath, and upland hay meadows occurs in Yorkshire – being concentrated in the Yorkshire Dales, North York Moors and Pennines.

Nature-rich habitats are generally found in upland areas where anthropogenic pressure is lower: Habitats in the lowlands are highly fragmented.

We have an obligation to conserve and enhance these priority habitats: However, the analyses of preferred habitats for Yorkshire Species of Concern showed that a broad range of habitats is needed if the full range of Yorkshire’s species is to be sustained.

Nature-rich habitats are generally found in upland areas where anthropogenic pressure is lower.

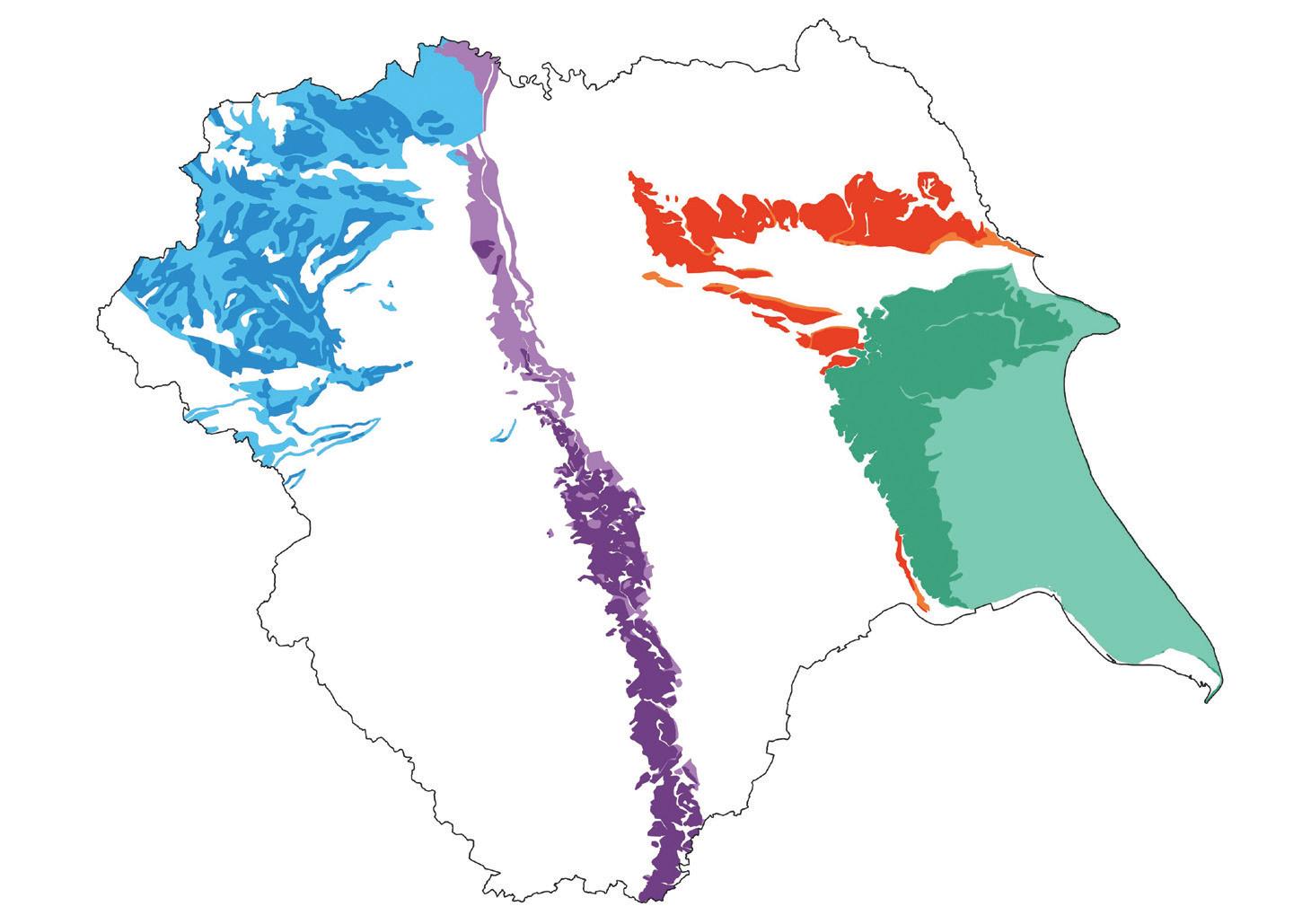

Distribution of Priority Habitats in Yorkshire. Red and brown represent blanket bog, upland heathland, upland calcareous grassland and dominate the uplands. Other colours represent habitats found in the lowlands.

Yorkshire Species of Concern have distinct habitat preferences:

Birds – open water and coast

Plants – grasslands and wetlands

Moths – woodlands and moorlands

Mammals – often a mosaic of habitats, including rivers and woodland

Overall wetlands play an important role in sustaining Yorkshire Species of Concern

The figure shows the percentage of Yorkshire Species of Concern that favour various habitats

Wet and limestone environments play a key role in determining terrestrial biodiversity for Yorkshire.

Different groups of species have distinct habitat requirements, so a wide range of habitats is needed if the full range of Yorkshire’s 40,000+ species is to be sustained. However, two kinds of environments are particularly strongly associated with species of conservation concern. Habitat recovery within those environments will bring large biodiversity and environmental benefits.

Wet habitats, ranging from open water through fens and bogs to wet woodlands and wet grasslands, are favoured by many Yorkshire Species of Concern across all groups examined. Almost half of plant species now extinct in Yorkshire were found in wetlands. Bringing water back onto the land will have huge biodiversity benefits, quite apart from helping flood control and carbon sequestration.

Limestone habitats are especially rich, and Yorkshire is unique in having four major geological limestone areas, all with a unique biological character. Almost half of the plants of Conservation Concern were associated with limestone/chalk.

have recolonised naturally and now breed on one of

Our unique geology has created four quite different areas across Yorkshire. The largest UK extents of Carboniferous limestone in the Dales, and Permian magnesian limestone running from north to south in the centre of the county; the Jurassic (dinosaurage) limestone on the south fringe of the North York Moors; and Britain’s most northerly outcrop of chalk (Cretaceous) on the Wolds. The differences in geology, topography and climate in each of these areas means that each supports a distinct set of plant and insect communities.

Three areas stand out for Yorkshire Plant Species of Concern: The Craven Pennines, the Humberhead levels and the Spurn peninsula.

Other areas of ‘interesting plant’ richness are the magnesian limestone belt that runs north-south, the Dales foothills area around Ripon, the limestone fringe of the North York Moors National Park and the River Hull valley.

Yorkshire Plant Species of Concern are also concentrated in the Pocklington Canal and on Thorne and Hatfield Moors, the chalk streams feeding the River Hull, which highlights the importance of wetlands and these particular waterbodies.

Places with large numbers of Yorkshire plant Species of Concern can indicate hotspots

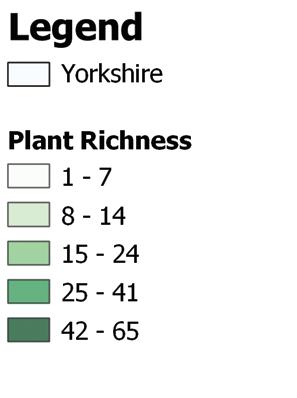

Areas with the largest number of plant, breeding bird and macro moth Yorkshire Species of Concern

Using data from other target groups (birds and moths) reveals further hotspots of biodiversity, including the Vale of York with sites/areas such as the Lower Derwent Valley, Skipwith and Strensall Commons, and Askham Bog.

Yorkshire is almost entirely within the Humber catchment: Most of the over 6,500 km of rivers and streams in Yorkshire drain into the Humber.

There are four natural lakes: All of these are SSSI and one (Malham Tarn) is a Special Area of Conservation (SAC) and the largest and highest marl lake in Britain, with an exceptional flora and fauna.

Numerous artificial lakes: Reservoirs, old gravel workings, and mining subsidences add to the still water area. Many of these are biologically important, especially for birds.

Yorkshire has a great variety and an extensive network of rivers, ranging from unmanaged upland streams to the Humber Estuary: This is due to its varied topography and complex geology. They support populations of nationally scarce or recovering species such as Otter, White-Clawed Crayfish, Freshwater Pearl Mussel, Water Vole, and River Lamprey.

The Esk catchment is the least impacted by human activity in Yorkshire: Water quality is good throughout its length, with healthy populations of invertebrates (Mayflies, Stoneflies, Caddisflies, and other pollution sensitive species) characteristic of clean, nutrient-poor low-calcium rivers. It also supports Yorkshire’s only Freshwater Pearl Mussel population and is an important river for Salmon and Sea Trout populations.

Almost all lowland rivers are intensively managed: As a result, rich aquatic plant communities are often confined to canals and ponds.

33 species of freshwater fish occur in Yorkshire: 73% of the British total.

There are three nationally recognised Salmon rivers in Yorkshire: The Lune, Ribble, and Esk, as well as the Tees which lies on the northern boundary. Other rivers such as the Ure are now welcoming back good numbers of Salmon and Sea Trout, and most rivers sustain robust populations of coarse fish.

Yorkshire has the northernmost chalk streams in Britain: such as the tributaries of the River Hull. These are an internationally rare and irreplaceable habitat.

Yorkshire’s lowland peatlands are nationally significant: The Humberhead Peatlands at just under 3,000 ha represent the largest area of raised bog wilderness in lowland Britain. The site is important, both as an example of a lowland raised mire and for its breeding Nightjars.

Yorkshire is a stronghold for England’s blanket bogs, covering more than 70,000 ha. Blanket bog is a mainly upland habitat, and is internationally important for wildlife as well as improving water quality, reducing flood risk, capturing and storing carbon.

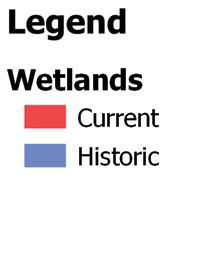

Lowland Yorkshire was once much wetter: Over 80% of our wetlands have been lost by drainage and river canalisation – with severe effects on wildlife.

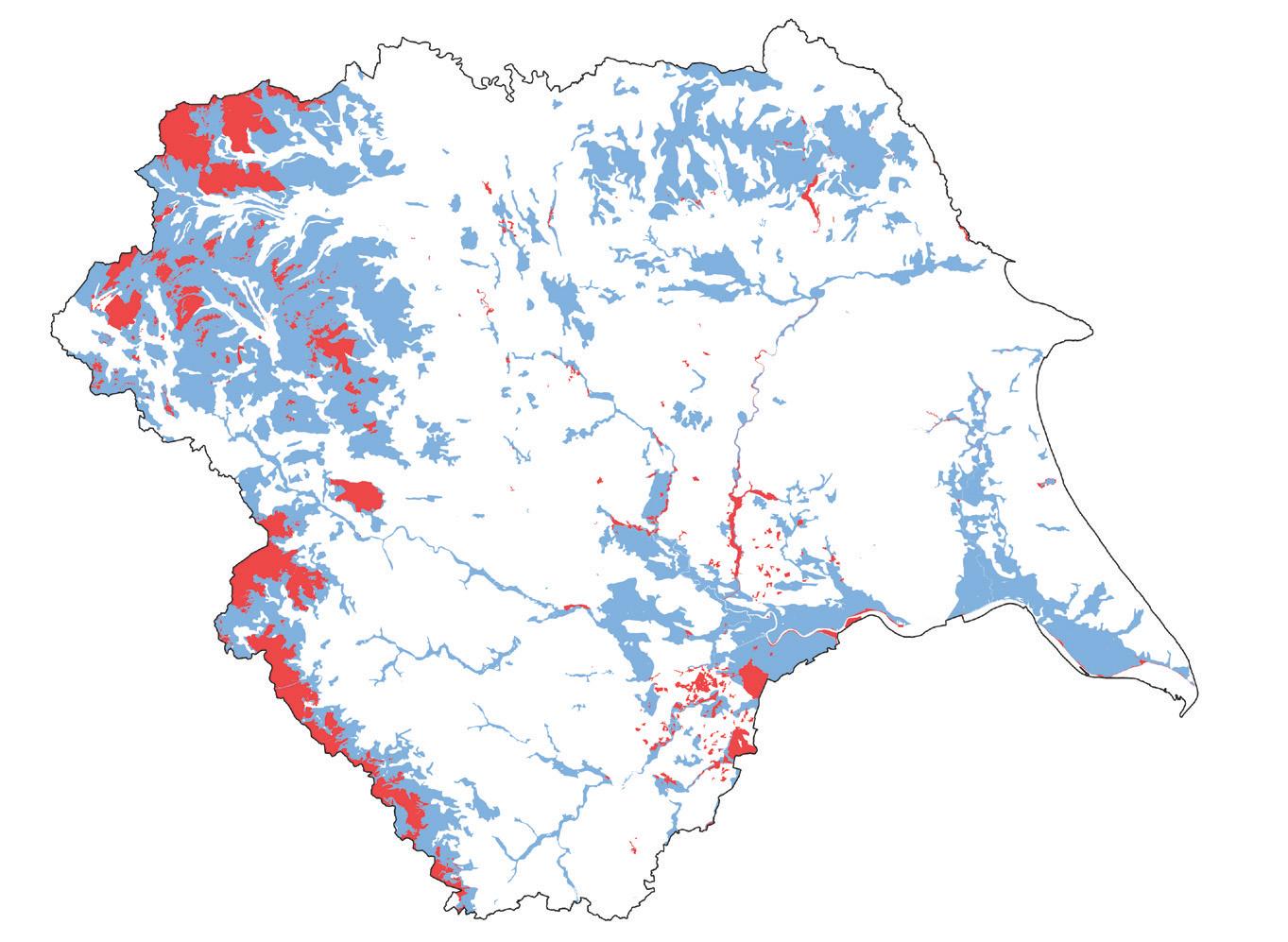

Nearly half of Yorkshire’s rivers have been physically modified: By lateral (canalisation, dredging) and longitudinal disconnection (weirs and other obstructions). These changes prevent fish from moving within the river network, and also divorce the river from its floodplain. This leads to loss of wetlands, reduces carbon storage on the land and exacerbates flooding downstream.

Since the 1970s, the quality of Yorkshire’s watercourses improved: Due to industrial decline, and better waste management and sewage treatment. However, new threats have emerged such as storm overflows, plastics and agricultural and urban pollution, and improvements are still needed.

Only 16% of Yorkshire’s rivers were in good ecological status in 2019: Lowland rivers, in particular, are in a poor state. This headline masks improvement in individual aspects of rivers; over 75% of ecological elements rated at least ‘good’, showing that improvement is possible and must be maintained.

80% of Yorkshire’s peatlands have been damaged or altered: Greatly reducing biodiversity, carbon storage and flood control.

Most of Yorkshire’s wetlands have been lost to drainage: only the areas shown red on the map survive (Source: Wetland Vision Project 2021.)

Artificial and heavily modified rivers in Yorkshire

The coastal and marine environment supports a mosaic of different habitats including chalk reefs, kelp forests, gravelly seabeds and rocky shores. These are home to wildlife of National and European importance.

The chalk continues into the sea: Flamborough Head is part of the most northerly outcrop of chalk in the UK, with the cliffs extending further seaward (as bedrock, boulder and cobble reefs) than in other areas in the UK.

The mixing of the cooler, deeper waters of the northern North Sea and warmer, shallower, well-mixed waters of the southern North Sea increases nutrient supply, plankton growth and productivity. As a result, the sublittoral and littoral reef habitats at Flamborough are the most diverse in the UK, supporting an unusual range of marine species including rich animal communities.

The kelp beds running northwards between Flamborough and Staithes are part of a vast North Sea network that soaks up a staggering 1,300 tonnes of organic carbon every year through photosynthesis.

Flamborough Head and the Filey Coast have one of the most important seabird colonies in Europe. The UK’s largest mainland breeding seabird colony includes the only mainland breeding Gannets in England and one of the largest populations of Kittiwakes in the UK.

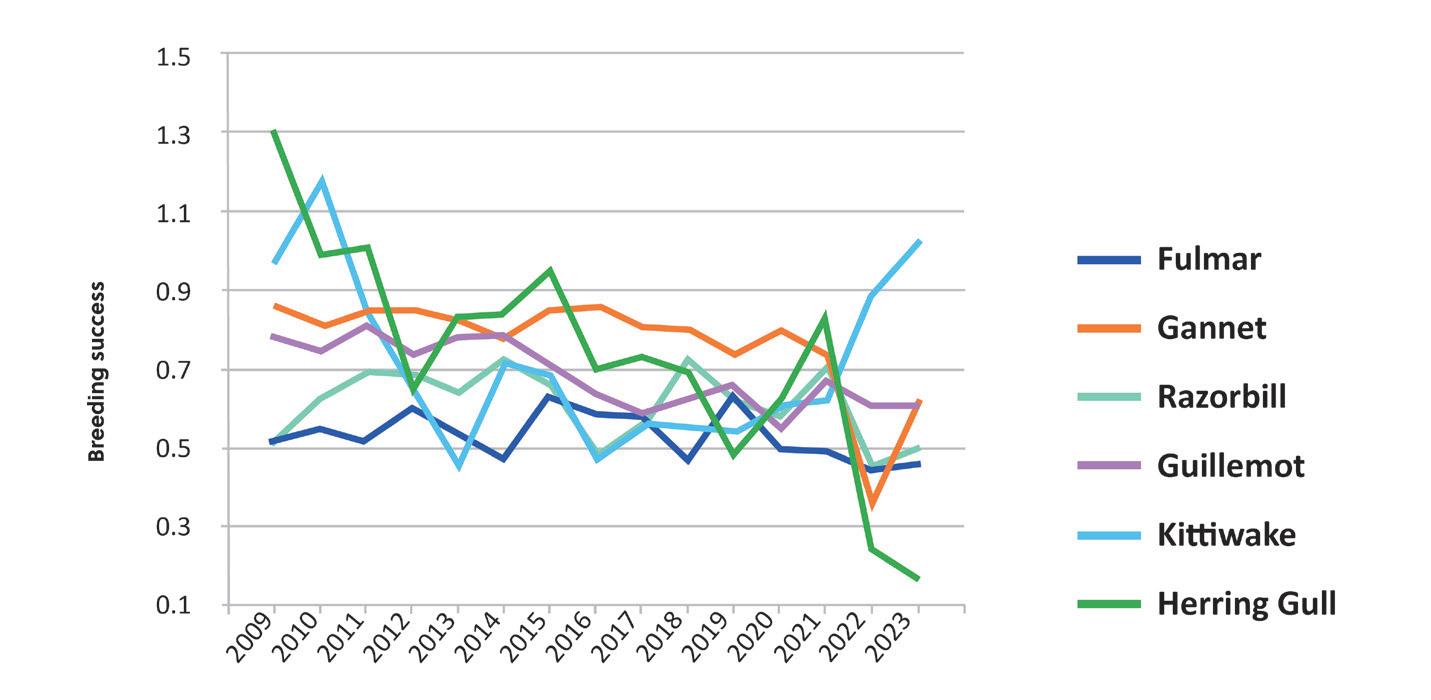

Seabird breeding success varies between species. In some it is declining (Herring Gull); in others it is relatively stable (Fulmar) or declining slowly (Guillemot). Kittiwakes are recovering from a long-term decline.

Yorkshire’s coastline stretches 152 km, from Redcar in the north to Spurn Point and the Humber Estuary in the south, with a ‘territorial’ limit that extends 22.2 km out to sea. The coastal zone is a complex interconnected network of marine and terrestrial species and processes.

The nutrients that flow from the Humber to the sea sustain fish populations that breed in the reefs and kelp-beds, and support huge sea-bird colonies. A healthy coast requires both land and sea to be well managed.

Seabird breeding success on the Yorkshire coast between 2009-2023 (RSPB and NE data)

The Humber Estuary’s key habitats include intertidal mudflats, sandflats, and saltmarshes: It also provides the main migratory route in Yorkshire for fish species such as Lamprey, Shad and Salmonids.

Some key habitats have almost vanished: Subtidal Seagrass beds are Critically Endangered in the European Red List of Marine Habitats, and both UK species of Seagrass (Common and Dwarf Eelgrass) are Nationally Scarce. Since 1900, the Seagrass meadow in the Humber Estuary off Spurn Point has shrunk by over 98% – from 480 hectares to only 7 ha. This is the last remaining patch of Seagrass in Yorkshire, which Yorkshire Wildlife Trust is working with partners to restore and enhance.

Keystone species are declining: Sand Eels are a hugely important part of the North Sea’s ecology. In fact, the fledging success of Yorkshire’s breeding Puffins –an IUCN Red List species – is entirely dependent on them. Climate change is forcing Sand Eels to move further north in

The North Sea, which includes Yorkshire marine waters, was once teeming with life. Oyster reefs and seagrass beds lined our estuaries, huge Tuna and other large fish were regularly caught and kelp forests and saltmarshes hugged our coasts.

But the North Sea now groans under the weight of pressure from human impacts. The current system of management has caused a decline in biodiversity and must be overhauled to bring about nature’s recovery. If we are to play our part in restoring ocean health we must urgently deliver drastic measures to enable recovery in the North Sea.

search of colder waters – resulting in Puffins travelling further and further away from their nests in search of this vital food source, leaving their vulnerable chicks alone, defenceless and starving. Every summer, more Puffin nests fail and fewer pufflings fledge.

The Humber Estuary’s conservation status was downgraded to Unfavourable condition by Natural England in 2012 due to habitat loss, commercial development, and the decline of precious habitats such as sand dunes, saltmarsh, seagrass, and native oyster beds.

Current protection is insufficient: While 35% of Yorkshire marine waters receive some form of protection (Special Area of Conservation, Special Protection Area, Marine Protected Area), they are not adequately managed to protect them from high impact fishing methods such as trawling and dredging. The condition of about 40% of sites has not even been assessed recently.

We need to manage and protect our marine environment with an ecosystem-based approach –instead of just focusing on localised areas. Bottlenose Dolphin have begun to visit Yorkshire more often, but we don’t understand why they are spending more time here and less in the Moray Firth in Scotland. Is this a good news story? Does this follow conservation action or does it indicate a much more complex and potentially alarming issue with food availability in Scotland? Bottlenose dolphin are a highly mobile apex predator, whose presence illustrates ecosystem health.

Scientific evidence shows that largescale conservation – a minimum of 30% of land and sea – is needed to restore biodiversity

The network of Protected Areas is at the heart of achieving 30 by 30 - where 30% of land and sea will be protected and managed for wildlife by 2030. Protected sites are important in forming the core components of nature networks, as they can provide strict statutory protection for valuable habitats and the species they support.

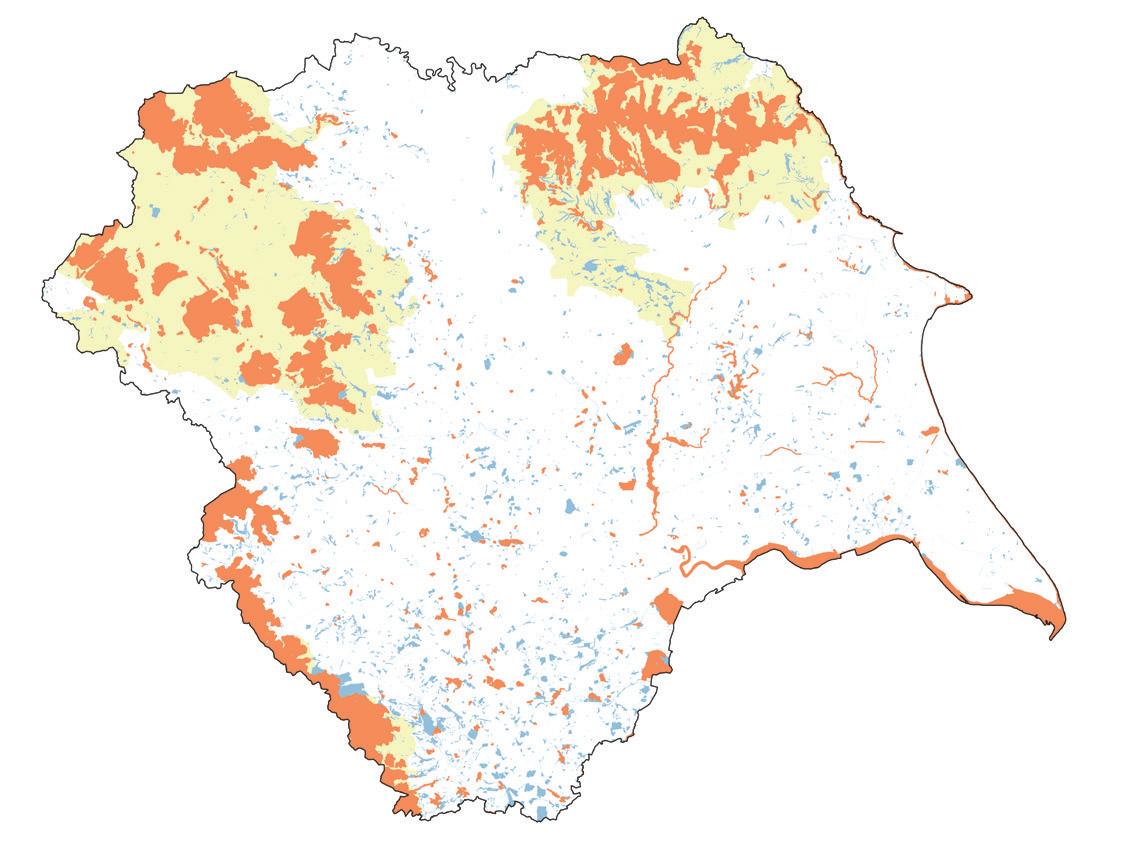

There are three tiers of land protection:

Tier 1 Statutory protection such as Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), Special Protection Areas (SPA) and Special Areas of Conservation (SAC), where the interests of wildlife should receive priority. Only 11% of Yorkshire’s land receives this protection, and it’s almost all in the uplands.

The distribution of Tier 1, 2 and 3 levels of land protection shows the importance of Tier 2 sites in the lowlands.

Tier 2 Non-Statutory protection are Local Wildlife Sites (LWS) and nature reserves managed by others including Yorkshire Wildlife Trust and local councils. These add another 4% to the protected area network. They are a large part of the protected area network in the lowlands.

Tier 3 Designated landscapes include National Parks and National Landscapes – concentrated in the north and west, these areas account for 28% of Yorkshire. They are designated for landscape quality not for wildlife, but they are large and sustain many habitats, and so provide significant opportunity for a contribution to nature’s recovery.

As well as protecting our surviving wildlife, Protected Areas act both as ‘landing pads’ for species whose range is shifting in response to climate change, and support the core populations from which recolonisation can occur. Under a rapidly changing environment, these are both critical functions of protected areas.

Black-winged Stilt successfully bred at Potteric Carr in 2022 – the most northerly known breeding in the UK. Their breeding range is shifting from Spain as climate change impacts wetlands.

Yorkshire’s Protected Area Network is extremely valuable: Many species now survive in Yorkshire because of these sites.

Plant and moth Yorkshire Species of Concern are much more likely to be found in or very close to protected sites (whether statutory or not) than in the wider countryside. In fact, all of the Yorkshire Species of Concern moths and all but 4 of the plants have at least 30% of their populations in or close to nature reserves. Over three-quarters of the plants species have at least 80% of their populations in or close to reserves.

Priority habitats are also wellrepresented in Tier 1 statutory protected areas: 15 of the 27 priority habitats have more than half of their area protected.

Most stronghold habitats have good statutory protection ranging from 62% - 86% coverage. However, only 30% of upland hay meadows have statutory protection.

The protected area network is therefore playing a hugely important role, despite only covering 15% of Yorkshire. However, is that because the sites have been designed to protect our vulnerable species, or because they have disappeared from most places outside reserves?

Sites across Yorkshire are too few, too small and too scattered to form the healthy and resilient ecological network that is needed to halt and reverse these declines.

Although some sites host important bird species, many are too small to sustain viable populations.

There are more than 270 SSSI in Yorkshire, and 69% are less than 50 ha with a median size of ~17 ha. This is true for an even higher percentage of non-statutory sites: 88% of Yorkshire Wildlife Trust reserves and over 90% of Local Wildlife Sites (LWS) across Yorkshire are less than 50 ha in size. The average golf course is bigger than that.

The large number of sites, small size, and low connectivity illustrates a highly fragmented network, particularly in lowland areas.

Most of Yorkshire’s SSSIs are in unfavourable condition

Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) are the foundation of a nature recovery strategy. They are where many species are clinging on, and where new species migrating in response to climate change will establish. But more than 80% of Yorkshire’s SSSI are in ‘unfavourable’ condition.

Along with legally-protected wildlife areas such as SSSIs, LWS support locally and often nationally threatened species and habitats. Many LWS in Yorkshire need updated monitoring so their condition is unknown, and of those that are monitored only 40% are in positive conservation management.

Without Protected Areas the state of the natural environment would be much worse; however, they haven’t stopped nature’s decline.

The protected area network alone cannot support a healthy and resilient environment. The wider landscape has a significant role to play for biodiversity, buffering protected areas and providing connectivity for wildlife.

Nearly three-quarters of Yorkshire is farmland. East Yorkshire (81% farmed) and North Yorkshire (79% farmed) are the most agricultural areas, with other areas about half farmed.

Increased demand for food and technological advances mean that much farmland is now intensively managed. The result is a less diverse landscape and much less natural habitat.

These changes are driven by agricultural policy, the economics of farming and consumer choices. Farmers have had little option but to rely on fertilisers, pesticides and mechanisation.

Different farming practices impact wildlife in different ways. Around a third of Yorkshire is arable (71% in East Yorkshire); another third is grazing and livestock (52% in North Yorkshire); and about 9% is mixed farming.

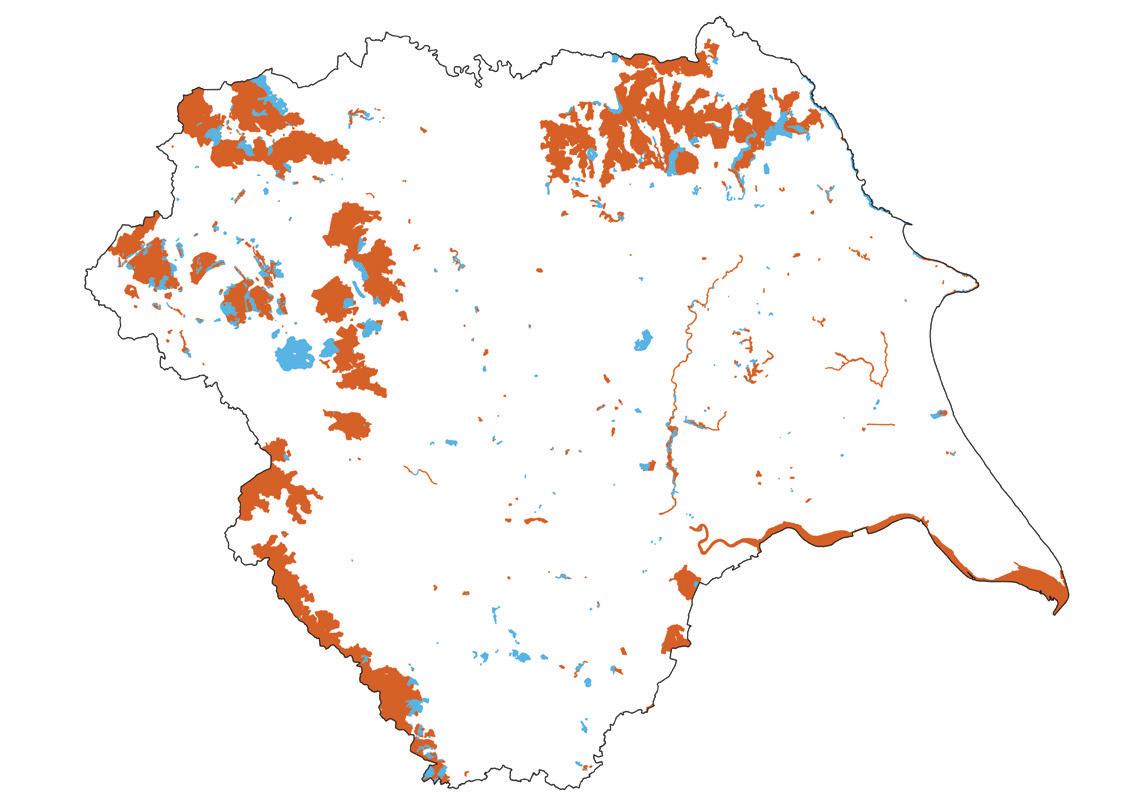

Lower grade agriculture (Grades 4 and 5) is concentrated in the uplands, coinciding with geographical hotspots of biodiversity, particularly in the Yorkshire Dales. Much of it is in protected landscapes (National Parks and National Landscapes) offering large opportunities for nature restoration.

The Provisional Agricultural Land Classification for Yorkshire shows where nature recovery is most likely to occur. Grade 1 is land of the highest quality and 5 is poorest.

High grade agriculture (Grade 1 and 2) is concentrated in the lowlands, particularly East Yorkshire and the central belt running north-south. Conversion of grazing land to arable on the chalk in the Wolds may explain why this area is less wildlife-rich than might be expected. Bringing wildlife-friendly habitat back to parts of these intensively farmed landscapes creates connections between isolated protected sites.

The challenge: how to make the farmed landscape better for wildlife without impacting food production and income.

Agri-environment and other incentive-based payment schemes can both support farmers and allow wildlife to thrive in lowland Yorkshire, particularly if there is emphasis on creating and joining up habitats.

In 2022, there were agrienvironment agreements on 42% of land holdings in Yorkshire (compared to 26% in England).

The area of land under agrienvironment schemes fluctuates because of the introduction of new schemes and the ending of previous ones. Even so, higher-level or targeted schemes are on average increasing nationally.

Urban and suburban areas cover around 10% of Yorkshire mainly in south and west Yorkshire. Smaller urban areas and villages are scattered across the region.

Urban areas can hold surprisingly large wildlife populations, including many species that have adapted to live alongside people (e.g. Pigeon, House Sparrow, rodents, Foxes, Hedgehogs and many plant species).

Natural habitats survive in many cities but are often isolated and suffer from pollution and heavy human impacts.

Residential gardens can make an important contribution to biodiversity in urban environments – in 2023 over 400 gardens across Yorkshire joined Yorkshire Wildlife Trusts ‘Wildlife Gardening Award’, contributing local action for nature.

Nature

Non-native plant species often establish first in urban areas when they spread from gardens: Himalayan Balsam was first introduced as a garden plant.

Non-native species can be benign or even welcome additions to biodiversity (Butterfly bush or Buddleia, Snowdrops and Collared Dove) or invasive and damaging (Rhododendron, Grey Squirrel and Box Moth)

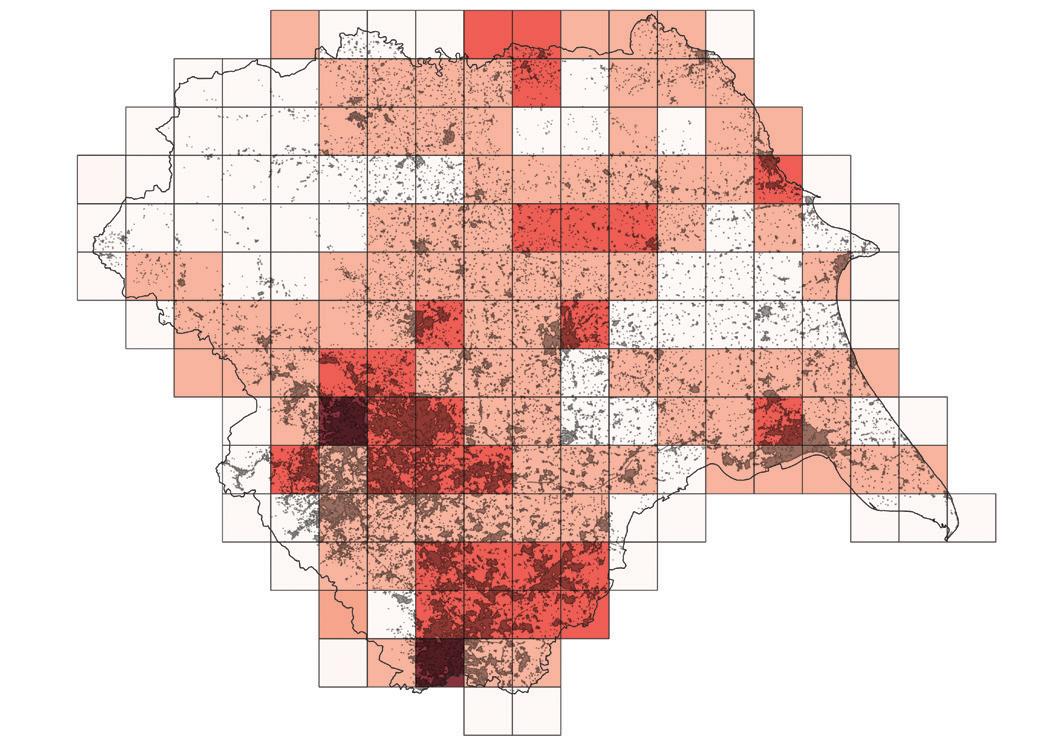

Urban areas stand out as the places where non-native plant species occur

Native species can be invasive and damaging too.

Stinging Nettle is known to respond strongly to nitrogen fertilisation and consequently is favoured by the high levels of atmospheric nitrogen pollution. It is the most widespread plant in Yorkshire (it occurs in over 3,000 2x2 km squares) yet has increased its range by 35% in the last 20 years, crowding out other less aggressive species.

in urban areas plays a crucial role in enhancing quality of life. Both physical and mental health is enhanced in ‘green’ cities, and for many people it is the easiest – sometimes only – way to build a relationship with nature.

Five take-home messages from this State of Yorkshire’s Nature report show where to focus interventions to accelerate nature’s recovery.

1

All habitats matter: There are over 40,000 species of plants, animals and fungi in Yorkshire, and each has its own ecological niche. Some groups have well-defined habitat preferences –dragonflies in freshwater for example –others have much more diverse ecologies. To sustain the biodiversity of Yorkshire, we must sustain and enhance the full range of habitats. This not only means protecting existing sites but growing and managing new wild and nature-friendly places across our county.

2 Irrespective of habitat, water and limestone promote biodiversity: Whether the habitat is woodland or grassland, wet habitats

support more Yorkshire Species of Concern than dry ones. This may be because we have drained so much of the landscape that their special species are now threatened.

Bring water back: Making habitats wetter will have huge benefits for biodiversity, while at the same time helping the land store carbon and water, mitigating climate change, reducing flooding and securing water supplies. It’s a win-win, and we can do it right across Yorkshire. We need partnerships to achieve this, with landowners, companies and regulators.

Habitats on limestone are rich ones: Many rare and threatened species are found on limestone, including the iconic Lady’s Slipper Orchid. Some are inherently rare: others are threatened because limestone soils are often productive agriculturally. Yorkshire’s limestone geology is uniquely varied and each has a different set of habitats and species:

Britain’s most northerly chalk in the Wolds

The largest area of magnesian limestone in the centre

Jurassic limestones in the North York Moors

The great Carboniferous limestones in the Dales.

restoration

Working with landowners, farmers and communities, the Wild Ingleborough partners are sharing skills and knowledge in land management. The project will connect existing nature reserves to create a larger area of land that is managed in a way that allows wildlife to thrive. The large-scale approach to habitat restoration will benefit wildlife and people, through carbon capture, flood reduction, job creation and improving both water quality and soil health.

Decades of pollution and development have resulted in significant loss and degradation of the Humber Estuary’s coastal habitats and species. To reverse these major declines, a partnership between Ørsted, Yorkshire Wildlife Trust and Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust is trialling a “seascape-scale” model, combining sand dune, saltmarsh, Seagrass, and native Oyster restoration to maximise conservation and biodiversity benefits across the estuary.

Yorkshire’s marine habitats are uniquely rich but threatened. Partnerships are needed to ensure the recovery of the mighty Humber Estuary to its former glory, to bring back thriving marine mammal and fish populations, and to sustain Yorkshire’s exceptional wealth of sea-birds.

Ambitious nature recovery needs landscape-scale work. The Lawton Principles of ‘more, bigger, better, and joined’ provide a robust and functional ecological network for Yorkshire. We need to create a multifunctional landscape that delivers for nature and people across Yorkshire, whether in the farmed lands, in cities, or in National Parks and Landscapes.

Sitting in the River Hull floodplain, Leven Carrs was once a vast expanse of wet grassland, marsh and open water. Following a long history of land use for agriculture, a 135ha wetland now sits in the middle of an arable working farm, and the Leven Canal Site of Special Scientific Interest dissects it. The site is at the heart of a network of areas managed for wildlife with Pulfin and High Eske lake only a short distance downstream and TopHill Low and Skerne Wetlands upstream linking up to the iconic headwater chalk streams of the upper Hull. This chain of wildlife habitats provides areas for species including Kingfisher and Otter to breed and opportunity for species such as Great White Egret to colonise.

A Landscape Recovery Project is currently assessing the possibility of transforming the surrounding farmland into a landscape-scale mosaic of wetland, woodland and heathland habitats, creating the Leven Carrs Nature Reserve. More and better quality habitats will provide homes for wildlife, including the threatened Water Vole, space for people to enjoy and conservation grazing land. As the Leven Carrs Nature Reserve, the site will be a special place for wildlife and people.

Measure success: Success in nature’s recovery is not measured just by areas of new habitat, but by the recovery of nature. The Index of Yorkshire Species of Concern enables objective measure of species recovery in Yorkshire.

Molescroft Wildlife Network are establishing wildflower meadows in prominent locations, working with their local council to implement sustainable management plans so that these areas will be managed for wildlife in perpetuity.

Being part of #TeamWilder has helped the group recruit new volunteers and attracted funding to enable them to realise their ambition of creating a wilder Molescroft.

“It gives us a feeling of wellbeing, knowing small groups like ours up and down the country are helping nature in various ways, collectively creating great benefit for wildlife. If you want to do something in your local area, be encouraged. The time is right, have a go, there will be other people who feel the same and you can make it happen!” Sharon Stone

The seeds from these meadow grasses and perennial wildflowers will increase biodiversity and help establish new thriving meadows.

“No-one can predict what our county will look like in 25 years’ time: there are too many unknowns. Climate change is a given but the details are uncertain – it’s likely to be hotter and wetter, but it is also possible that it will be colder if the North Atlantic Circulation slows. Invasive species, especially diseases, are bound to arrive and spread, but we don’t know which and we don’t know what impact they will have. These things are hard to control.

Other things, are however in our hands: whether agricultural policy favours biodiversity, whether we clean up our rivers and re-connect them with their catchments, and how we manage our seas – these we can change.

Get these things right and we will have created the habitats, ecosystems and environments for nature and people to thrive. And Yorkshire in 2050 will be an even better place to live, rich in wildlife with clean air and waters, and a prosperous and healthpromoting environment.”

Professor Alastair Fitter, CBE FRS Trustee Yorkshire Wildlife Trust

A vision for Yorkshire – nature-rich and resilient, with thriving ecosystems

ILLUSTRATION

The State of Yorkshire’s Nature report has been created thanks to extensive work by Yorkshire Wildlife Trust’s Nature Recovery Directorate, alongside Professor Alastair Fitter, Sir John Lawton, the Trust’s Nature Recovery Committee and partners including the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO), the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland (BSBI), Butterfly Conservation (BC) and the Yorkshire Naturalists’ Union (YNU).

We are grateful to the dedicated efforts of generations of naturalists who have recorded Yorkshire’s wildlife, and for your support, without which we could not have undertaken this report or developed our strategy. By continuing – even extending - this invaluable recording, the community of Yorkshire naturalists will make it possible to assess our collective success in restoring Yorkshire’s nature.

This work establishes the baseline of Yorkshire’s nature. It is part of an iterative process, evolving over time in line with emerging data and technologies. If you have any feedback, find any errors, or would like to contribute data to future editions, we would like to hear from you. Please get in touch by contacting ywt.data@ywt.org.uk