YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY

YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY COUNCIL MEMBERS

CHAIR

Philip L. Pillsbury Jr.*

VICE CHAIR

Bob Bennitt*

COUNCIL

Hollis & Matt Adams*

Jeanne & Michael Adams

Gretchen Augustyn

Susan & Bill Baribault

Meg & Bob Beck

Suzy & Bob Bennitt*

David Bowman & Gloria Miller

Tori & Bob Brant*

Marilyn & Allan Brown

Steve & Diane Ciesinski*

Sandy & Bob Comstock

Hal Cranston*

Carol & Manny Diaz

Leslie* & John Dorman*

Dave & Dana Dornsife*

Lisa & Craig Elliott

Kathy Fairbanks

Sandra & Bernard Fischbach

Cynthia & Bill Floyd*

Jim Freedman

Susan & Don Fuhrer*

Bonnie Gregory

Rusty Gregory*

Karen & Steve Hanson

Chuck & Christy Holloway*

Christina Hurn & Richard Tassone

Jennifer & Gregory Johnson*

PRESIDENT & CEO

Frank Dean*

VICE PRESIDENT, CFO & COO

Jerry Edelbrock

Jean Lane

Walt Lemmermann*

Melody & Bob Lind

Sam & Cindy Livermore

Anahita & Jim Lovelace

Mark Marion & Sheila Grether-Marion

Patsy & Tim Marshall

Kirsten & Dan Miks

Robyn & Joe Miller

Janet Napolitano

Dick Otter

Sharon & Philip Pillsbury*

Bill Reller

Pam & Rod Rempt

Frankie & Skip Rhodes*

Liz & Royal Robbins

Dave Rossetti & Jan Avent*

Lisa & Greg Stanger*

Jennifer & Russ Stanton*

Ann & George Sundby

Susan & Bill Urick

Clifford J. Walker*

Wally Wallner* & Jill Appenzeller

Jack Walston & Sue Estes

Phyllis Weber* & Art Baggett

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK

Superintendent Don Neubacher

*Indicates Board of Trustees

MISSION

Providing for Yosemite’s future is our passion. We inspire people to support projects and programs that preserve and protect Yosemite National Park’s resources and enrich the visitor experience.

PRESIDENT’S NOTE

Yosemite’s Wilderness

he word wilderness might sound forbidding, or it might conjure up a sense of adventure. In an increasingly crowded world, national parks — and their protected Wilderness areas — provide important space, solace, and a refuge for both wildlife and humans. Some years ago, I had the privilege to ski with good friends into a snowed-under Tuolumne Meadows. We had the meadows to ourselves and enjoyed a full moon that reflected off the snow to make it

almost as bright as daylight. It was an amazing experience.

More than 95 percent of visitors to Yosemite spend their time in Yosemite Valley, Mariposa Grove, or along Tioga Road. By comparison, the Yosemite Wilderness is relatively lightly used, yet hikers seek more permits than the resource quota allows for the most popular trails. Backpacker use of the John Muir Trail between Yosemite and Mt. Whitney is at an all-time high.

The popularity is not surprising, as the beauty and inspiration provided by exploring the Yosemite high country is magical. However, the park’s Wilderness is also fragile. Conservancy donors support many projects to help preserve Yosemite’s Wilderness. Grants for trail rehabilitation, habitat restoration and wildlife research reduce the effects of human impact, so that inspirational and magical experience remains for the next generation. You can read about some of these important projects, such as restoring habitat in Lyell Canyon and extending park boundaries to include Ackerson Meadow, in the following pages. The Yosemite Wilderness is yours to enjoy, so thank you for making these projects possible through your financial support.

Thanks for all you do for Yosemite!

Frank Dean, PresidentCOVER PHOTO A visitor enjoys the John Muir Trail through Cathedral Meadow, a designated Wilderness area, on her way to Cathedral Peak, in the distance. PHOTO: © JENNIFER MILLER.

We are now on Twitter and Instagram! Follow Yosemite Conservancy, and stay connected.

SPRING.SUMMER 2016 VOLUME 07.ISSUE 01

IN THIS ISSUE DEPARTMENTS

04 RESTORING YOSEMITE’S WILDERNESS CHARACTER

Programs restore the untrammeled beauty of Yosemite’s designated Wilderness areas, while protecting native wildlife and sensitive habitats.

08 LEAVE NO TRACE: A STARTER’S GUIDE

Whether in Yosemite Valley, Wawona or deep in the backcountry, every visitor can follow these simple steps to protect our park.

10 RESTORATION IN PICTURES: A BEFORE & AFTER STORY

Side-by-side pictures reveal the hidden story of wilderness restoration, from trails to meadows to illegal campfires.

12 EXPER T INSIGHTS

Resource manager Linda Mazzu shares the excitement of expanding Yosemite’s borders with the protection of Ackerson Meadow.

14 Q&A WITH A YOSEMITE INSIDER

Yosemite botanist Garrett Dickman explains how planting native species saves pollinating wildlife in Yosemite.

16 GRANT UPDATES

Preserving habitat in Lyell Canyon; restoring beloved Yosemite trails; saving frogs and turtles; and researching rare flora.

22 PROGRAM

UPDATES

Outdoor Adventures explore little-known wonders; theater programs celebrate the National Park Service centennial; and a new memoir remembers rock-climbing’s golden age.

31 DONOR EVENT S

Join a community of like-minded individuals to connect to Yosemite.

32 WHY I GIVE

Conservancy donors share their stories of inspiration and passion.

34 READER PHOTOS

Yosemite Conservancy supporters share their special Yosemite memories.

“

WILD” KEEPING THE

IN WILDERNESS

PROJECTS PRESERVE YOSEMITE’S WILDERNESS

hat is wilderness? That seemingly simple noun conjures up a host of images and associated adjectives: undeveloped, rugged, wild. The 1964 Wilderness Act, which established a national network of places “protected and managed so as to preserve [their] natural conditions,” defined Wilderness, with a capital W, as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

Where that definition stops, our relationship with wilderness begins. We, the human visitors who do not remain, embrace the recreational experiences wilderness offers, prize pristine landscapes as havens for plants and animals, and connect with the symbolic value of primeval spaces as reminders that we are relative newcomers on a shared, biodiverse and ancient earth.

All these human–nature relationships find a home in Yosemite. Every year, thousands venture into the park’s 704,624-acre designated Wilderness to experience a remarkable landscape of smooth granite domes and jagged peaks, still lakes and crashing waterfalls, ephemeral wildflowers and age-old trees. And every year, our donors help ensure those wild acres are preserved and managed, so they remain untrammeled for generations to come.

This August marks 100 years since President Woodrow Wilson created the National Park Service. The idea for

“Wilderness is a place to calm the mind, clear the lungs and rejuvenate the spirit, but it is also a place to strengthen one’s mental, emotional and physical traits.”

— LAURIE STOWE

Wilderness Program Manager

establishing that federal agency, which today oversees nearly 44 million acres of the nation’s designated Wilderness, has roots in Yosemite. A century before the Wilderness Act, the Valley’s majestic features and Mariposa Grove’s towering sequoias helped inspire the 1864 Yosemite Grant Act — groundbreaking legislation that spurred a movement to set aside protected areas as national parks. Much later, in 1984, Congress officially designated the Yosemite Wilderness, which now accounts for nearly 95 percent of Yosemite National Park.

Designating land as Wilderness, however, does not ensure it will remain undeveloped and wild. According to Elissa Kretsch, Yosemite’s wilderness education coordinator, Conservancy donors play a big part in protecting the park’s Wilderness and ensuring everyone can appreciate the remarkable, rare experience of being a guest in a place where nature is allowed to prevail.

“Our love of wild places is the biggest threat to Wilderness areas,” Kretsch says, noting that hikers can inadvertently affect their surroundings in many ways, such as by transporting invasive plant seeds on their boots, creating social paths or building campsites in sensitive areas. “Conservancy-funded projects not only repair this unintended damage, but also increase the

resiliency of Yosemite’s Wilderness to human-induced change.”

The major goals of wilderness restoration, including restoring natural processes, slowing erosion, improving water quality and reconnecting fragmented habitat, feature prominently in Conservancy-funded projects. This year, for example, donors are funding efforts to remove invasive plants in high-elevation meadows, to reestablish sequoia habitat and natural water flow in Yosemite’s three sequoia groves, and to restore wilderness character by removing informal campsites and restoring trails through the Keep it Wild program. Such restoration activities also encourage prevention. Since the Conservancy started funding Keep it Wild in the 1980s, the park has seen a steady downward trend in the number and size of inappropriately located campsites.

In many cases, wilderness-preservation projects start with understanding human nature. By looking at numerous social paths created around Cathedral Peak, crews identified and stabilized the most heavily used, durable trail, which helped consolidate foot traffic and minimize impacts on the landscape. Last year, a similar approach was used to remove unsafe social trails near Vernal Fall, protecting hikers and fragile spray-

zone plants alike. Ongoing work to reroute sections of the John Muir Trail and restore wetland in Lyell Canyon (see p. 20) emerged from research showing that hikers were trampling sensitive meadow habitat to avoid muddy trails.

Truly preserving Wilderness not only involves restoring the “untrammeled” nature of a protected place, but also requires protecting the “community of life.” The animals that make their homes in the Yosemite Wilderness are as integral to the landscape as mountains and meadows. Donor-funded projects help protect wildlife in the park’s Wilderness in many ways, from planting flowers for bees, butterflies and other pollinators that fill a crucial niche in healthy ecosystems; to studying and protecting endangered species, such as great gray owls and Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep; to tracking black bears with new GPS collars to keep bears wild and visitors safe.

Your support for projects that restore habitats and trails and protect wildlife benefits Yosemite’s Wilderness in countless ways, year-round. If you’re looking for evidence of wilderness restoration, however, don’t look too hard. As Kretsch reminds us, “The best wilderness restoration is where you cannot see that it was needed at all.”

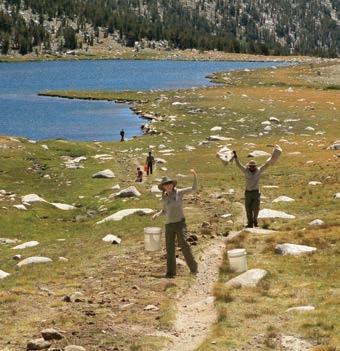

TOP With more than 704,000 acres of designated Wilderness (nearly 95 percent of the park), Yosemite is a protected haven for pristine natural resources, diverse species and unparalleled views. BOTTOM The Conservancy’s naturalist-led Outdoor Adventures offer ample opportunities to explore the Yosemite Wilderness, including backpacking treks and high country day hikes.

ACE Leave NoTrace BE A ACE

SIMPLE STEPS ANYONE CAN TAKE TO HELP PROTECT YOSEMITE

eave No Trace. These three little words capture a huge idea: We can — and should — minimize our impact in the outdoors. The concept, born in the 1960s in response to increased visitation at parks and other public lands, was formalized in 1994 as the nonprofit Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics.

“Everyone can participate in wilderness protection, and they should — it’s their land, too!”ELISSA KRETSCH Wilderness Education Coordinator

Many projects you support in Yosemite help erase and prevent human “traces” in the park’s wilderness, by removing social trails, restoring sensitive habitats and more. Park professionals lead these projects, but they aren’t the only ones with a part to play. With a few simple steps, each of us can become an active ambassador for the wild places we love.

As an official Leave No Trace (LNT) partner, Yosemite Conservancy urges people to do their part to protect the park. Our donors support programs that encourage young people to appreciate and care for their natural surroundings. Wilderness team members promote LNT principles while helping backpackers reserve permits and rent bear-proof food canisters, and Outdoor Adventure guides incorporate LNT practices into every experience.

Check out our no-trace tips at right, and don’t forget to use a whisk broom or brush to wipe any plant seeds off your boots, clothes and tent before and after your trip.

LNT encourages you to leave everything you find in the wilderness, but here’s one thing we hope you always take home from your Yosemite visits: A sense of wonder and appreciation for an incredible natural place you help protect. By supporting wilderness restoration and practicing LNT principles, you’re making a difference in Yosemite.

Here’s a simple guide to use LNT principles to make your mark in Yosemite — by not making a mark!

Respect signs.

Way-finding and safety signs help you stick to designated trails and viewing areas, protecting you and the surrounding habitat.

Keep wildlife wild.

Observe animals from a distance. Don’t feed wild animals! Use bearproof lockers to store food at campgrounds and parking areas.

Indulge in eco-friendly self-expression.

Memorialize your nature experience in a poem, sketch or photograph, rather than by carving into a tree trunk or mossy rock.

Leave what you find.

Pocketing a pinecone may seem innocuous, but trees rely on cones to reproduce and grow, providing shelter and food for animals. Removing one cone, flower or rock might seem small to you, but imagine if each of Yosemite’s 4 million annual visitors did the same thing.

Don’t leave anything else.

Use receptacles to dispose of litter — including crumbs, apple cores and orange peels. Even better: Bring your own bags, and carry out your trash.

TIPS TIPS SHORT VISITS & DAY HIKES

BACKCOUNTRY BASICS

Plan ahead.

Talk to rangers about your route, get permits and bear-proof food canisters, and respect wilderness quotas to help minimize impact on backcountry trails and campsites.

Stay on durable surfaces.

Use existing trails and campsites. If you need to chart your own course, step and camp lightly: One study found that sites camped on for four nights take eight years to recover fully. When heading off-trail, spread out to avoid creating social paths, and pitch your tent on a durable surface, such as rock, dry grass or snow.

Pack everything out.

Yes, everything — that includes food scraps and toilet paper. Plan meals to avoid leftovers, and bring only what you need to stay fed, warm and safe.

Respect the 200-foot rule.

Wash dishes, pitch tents and dispose all waste at least 200 feet from streams and lakes to avoid contaminating water.

Practice clean cooking.

Stick to stoves and lanterns. If you need to build a fire, keep it small, douse it with water when finished, and scatter the cool ashes.

Restoring Wild Lands

A STORY IN PICTURES

tep into Yosemite’s Wilderness, and you immerse yourself in the raw beauty of the Sierra, from rugged granite mountains to rushing waterfalls. Each year, more than 15,000 people explore wilderness areas, sometimes inadvertently leaving their mark on the landscape. Conservancy donors frequently support the park’s hardworking wilderness restoration crews tasked with protecting sensitive habitat and restoring wilderness character. These workers do such a great job, you’d never know they were there! These images from Conservancy-supported restoration projects highlight the dramatic changes made by crews who restore the “wild” to Yosemite’s Wilderness.

Upper Cathedral Meadow

Upper Cathedral Meadow

UPPER CATHEDRAL MEADOW is a flourishing natural ecosystem that supports Yosemite’s plants and animals. To protect this resource, more than a half-mile of networked trail ruts were restored to natural conditions, and the trail was rerouted from sensitive meadowland to resilient upland forest.

KEEP IT WILD programs connect youth conservation groups with Yosemite park rangers to restore wilderness. This inappropriately located campsite and fire circle is less than 100 feet from a water source. Removing and disguising the site prevents future campers from using it and helps keep the water clean.

GAYLOR LAKES and the surrounding meadows provide stunning scenery and prime habitat for the Yosemite toad. In 2013, restoration crews and youth volunteers restored deep trail ruts (formerly 5–13 inches in depth) to create a single hiking trail through dry ground.

The special-status pansy

MIDDLE Ackerson Meadow’s 400 acres of mid-elevation habitat support diverse plant and animal species. RIGHT Many songbird species, including endangered willow flycatchers, make their year-round or seasonal homes in this

ACKERSON MEADOW

EXPANDING YOSEMITE’S ECOLOGICAL DIVERSITY

BY LINDA MAZZU, RESOURCE MANAGER, YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARKtanding on a large rock within Ackerson Meadow, I marveled in the lovely spring day. In every direction, I saw meadow and forest edge, while a pink, yellow and purple carpet of the rare pansy monkeyflower lay at my feet.

This year, Yosemite National Park will “grow” by about 400 acres on its western border to encompass the Ackerson Meadow complex. This formerly private property will be protected for the public and for the wildlife that live here. Mid-elevation meadows, such as Ackerson Meadow, and their surrounding forests are the ecological gems of the Sierra Nevada. These meadows retain snowmelt in their wet soils, which grow lush patches of willows and numerous species of plants and shrubs, often bounded by mature forest. This combination of habitats is where we find the highest number of plant and animal species anywhere in Yosemite.

LEFT monkeyflower (Mimulus pulchellus) blooms in abundance in the meadow. natural haven in the western Sierra Nevada.

PROJECT SUMMARY

Studies in Ackerson Meadow reveal a flourishing food web. Numerous plant species attract an equally impressive number of pollinating insects, which in turn, attract small mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians. The forest edge provides ample perching opportunities for raptors, such as northern harriers and American kestrels, and cover for larger mammals. To me, there is no more perfect example of an ecosystem in motion than Ackerson Meadow.

Ackerson Meadow does not exist in isolation; it is part of a sprawling network of meadow systems. Protecting this area as part of an intact meadow system helps the numerous rare and unique species that use the meadow complex in its entirety. Such species include western pond turtles, great gray owls, grasshopper sparrows, pallid bats and other rare bat species. In addition, Ackerson Meadow is one of the few mid-elevation meadows reliably used by the endangered willow flycatcher.

As I stood there on that rock in Ackerson Meadow, stories to be told about the unique natural and cultural history of this area were already forming in my head. As a resource manager for the National Park Service, there is no greater accomplishment than enhancing the protection of ecological diversity and wildlife connectivity. Through projects such as this one, Yosemite Conservancy contributes to the history of landscape conservation for Yosemite National Park. We should all be very proud of this amazing effort.

In 2016, the 400-acre Ackerson Meadow will be purchased and made part of Yosemite National Park. This acquisition is made possible through collaboration among The Trust for Public Land, the National Park Service, Yosemite Conservancy, the National Park Trust, American Rivers and the Sierra Nevada Conservancy. The meadow was homesteaded in the 1880s and included in the original 1890 Yosemite National Park boundary. Adjustments in 1905 excluded the property from the park. In 1937, the meadow’s southern edge was added back to the park. With this partnership, the remaining portions will again be part of Yosemite National Park.

LINDA MAZZU leads Yosemite’s resource management and science teams as the division chief. She has worked for the National Park Service for most of her 34-year career. Though Mazzu has had the pleasure to work in a variety of landscapes, she finds the greatest inspiration from the scenery of Yosemite and the Sierra Nevada. Mazzu works with an amazing group of scientists and resource managers to protect the future of Yosemite’s natural and cultural heritage through science, scholarship and informed stewardship.

“Native

plants feed pollinators:

insects and animals looking for sweet nectar or fatty proteinrich pollen from flowers.”— GARRETT DICKMAN Botanist & Resource Management Park Ranger

Q&A

WITH A YOSEMITE INSIDER

ark ranger and botanist Garrett

Dickman has surveyed land across the West, searching out invasive plants. He joined Yosemite National Park as a ranger in the wake of the Big Meadow Fire, which burned 7,425 acres on the west side of the park. As part of the fire-recovery efforts, Yosemite needed biologists to survey plant life. With a recent graduate degree in ecology from Montana State University, Dickman found the timing was perfect to put his years of knowledge and experience to service for Yosemite. He says accepting this position was like “finding love.”

Q :: Your specialty is invasive plants. Why are invasive plants disruptive to Yosemite?

A :: Invasive or non-native plants are species that have serious potential to displace native plants. From an ecological perspective, the staggering immensity of sequoias, the improbable blue sky pilot flowers, the blinding yellow of spring poppies and the gracefully arched black oaks are critically important. If we lose these native plants, we lose part of the identity of this place. Our work helps maintain that sense of place for years to come.

Q :: Yosemite Conservancy is supporting a project to replant native species to save pollinators. Why is this important?

A :: Native plants feed pollinators: insects and animals looking for sweet nectar or fatty protein-rich pollen from flowers. In their search for food, they disperse pollen and inadvertently help plants reproduce. Pollinators include insects, such as bees, wasps, flies, butterflies, moths and beetles; as well as birds, bats and mammals. Yosemite provides a protected haven for migrating pollinators, such as the monarch butterfly and various hummingbird species. Yosemite’s migratory birds and insects may also pollinate the food growing in California’s Central Valley. As pollinator populations across the nation are crashing, it is important to protect their wild food sources.

Q :: How do youth volunteers contribute to the health of Yosemite’s native plants?

A :: Youth groups provide key support for this project to replant native species. Students from NatureBridge, a youth environmental science program, spent the fall collecting seeds and removing non-native plants. This summer, a group of students will plant pollinator-friendly species as part of a youth symposium celebrating the centennial of the national park system. Students will take away a sense of accomplishment and a connection to Yosemite, as well as the knowledge they can make an impact to protect wildlife in parks or at home.

Q :: What do you love about your work in Yosemite?

A :: I never have to remind myself how lucky I am to live and work here. Thanks to the work we do, Yosemite visitors will see areas previously taken over by non-native grasses covered once again with wildflowers.

Q :: How important is the Conservancy’s role in supporting your work?

A :: True protection takes much more than a “national parks” label; it takes a public that believes in preserving our shared heritage. Many of the projects I work on would not be possible without the support of Conservancy donors.

ABOVE The monarch butterfly is completely dependent on milkweed for its survival, and places such as Yosemite offer protection for this often-overlooked plant.

Thank you to Jack and Sheri Overall for generously providing significant funds in support of this project.

RIGHT Before digging up invasive thistle with shovels, youth volunteers remove flower heads so plants won’t spread seeds.

From books to apparel, the Yosemite Conservancy Bookstore has great finds for the Yosemite-lover in your life.

Each purchase benefits the park — just one more way for you to show your support for Yosemite. Shop now at

New Grants for 2016*

CULTURAL & HISTORIC PRESERVATION

Create an Online Yosemite Museum Gallery

Modernize the Yosemite Research Library

Preserve the Pioneer Yosemite History Center

Preserve Yosemite’s Horse & Mule Tradition

Special Exhibit: 90 Years of the Yosemite Museum

HABITAT RESTORATION

Improve John Muir Trail & Meadow Habitat in Lyell Canyon

Keep It Wild: Restore Yosemite’s Wilderness

$29,904

$30,200

$55,000

$20,000

$123,664

$143,540

RESTORING TREASURED TRAILS

$199,980 Plant Flowers to Save Pollinators

Protect Ackerson Meadow

Restore Alpine Meadows: Remove Invasive Plants

SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH

Every Drop Counts: Monitor Yosemite’s Snowpack & Water Resources

Protect Songbirds & Inspire Visitors

$95,650

$500,000

$52,548

$51,008

$51,628

Rare Flora Research: Yosemite’s “Fire-Followers” $87,496

Save Our Sequoias: Protect Yosemite’s Giant Sequoia Groves

TRAIL REHABILITATION & ACCESS

CCC Crews Restore Trails: Merced Watershed

$82,200

$233,500

CCC Crews Restore Trails: Matterhorn Canyon $234,072

Restore Legendary Valley Trails

Restore Popular Climber-Access Trails

VISITOR SERVICES & EDUCATION

Adventure Risk Challenge: Youth Build Skills in Yosemite

Ask a Climber

$365,000

$80,000

$95,000

$45,750

Connect the Class of 2016 to Yosemite $35,000

Inspire Kids: Junior Ranger Program

Keep Visitors Safe with Preventive Search and Rescue

Parks in Focus: Youth Experience

Yosemite through Photography

Parsons Memorial Lodge Summer Series

Replace Search and Rescue Tent Housing

WildLink: Teens Explore Yosemite & Conservation Careers

Yosemite Leadership Program: Shaping New Stewards at UC Merced

Yosemite Leadership Program: Summer Internships in the Park

WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT

Keep Bears Wild with Advanced Technology

Protect the Sierra Nevada Red Fox

Protect Yosemite’s Owls

Restore Rare Frogs & Turtles

Return Bighorn Sheep to the Heart of Yosemite’s Wilderness

$125,000

$50,000

$24,000

$45,000

$13,774

$49,271

$100,000

$120,298

CARING FOR YOSEMITE VALLEY’S

MOST POPULAR TRAILS

$79,000

$62,100

$97,310

$185,064

$83,100

TOTAL $3,645,057

*Color represents 2016 Youth in Yosemite Programs.

ick a trail to hike in or around Yosemite Valley, and before long, you’ll be enjoying a tranquil walk in the woods, marveling at a thunderous waterfall or taking in jaw-dropping views. Those timeless Valley trails provide access to some of the park’s most iconic landmarks — and thanks to your support, Yosemite’s crews are making sure those trails match their high-caliber settings.

You’ve probably spotted trail restoration work without knowing it: in stone steps, nonasphalt surfaces and helpful signs. This year is a special one for the trail crew: The restoration of Yosemite’s legendary Valley trails was identified as one of 106 projects selected in 2016 for the National Park

Service’s Centennial Challenge, which aims to ensure parks are prepared to preserve natural resources and provide top-notch visitor experiences for centuries to come.

Your

support ensures trails, such as the popular John Muir Trail, offer safe, enjoyable and environmentally sound experiences for visitors as they explore the park’s natural wonders.

To meet that challenge, crews are focusing on completing major renovations at the heavily used trailhead near Happy Isles, which provides access to Vernal Fall, Nevada Fall and Half Dome via the Mist and John Muir trails. The next time you’re in that area, note the fresh fencing, way-finding and safety signs, and sustainable trail tread. Later in the season, the crews will head toward Clark Point to install StaLok®, a self-healing, smooth, environmentally sound surface material, on a 1,000-foot section of the John Muir Trail. With your support, these projects are transforming some of Yosemite’s most beloved trails, and improving access to waterfalls and other natural wonders for visitors today and in the future.

LEFT Backpackers enjoy a view of Nevada Fall as they head back from the high country along the John Muir Trail. RIGHT Crews install a semi-porous material on a section of the trail below Vernal Fall, creating a smooth surface and allowing for healthier water flow than asphalt tread.

SAVING RARE FROGS & TURTLES

BIOLOGISTS AID POPULATIONS OF

SEMI-AQUATIC SPECIES

nce plentiful in Yosemite’s wilderness, frog and turtle populations have greatly decreased due to habitat degradation and disease. Though small in scale, these creatures play an important role in the Sierra ecosystem, filling a niche as predators, prey and indicators of environmental stresses.

In the past, Conservancy donors have supported the recovery of Yosemite’s endangered Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frogs through projects that have honed techniques for identifying suitable habitat and relocating amphibians. This year, while continuing to introduce yellow-legged frogs to mountain lakes, biologists are expanding their focus to two other special-status species. At least 1,500 California red-legged frogs and 10 western pond turtles will be released in Yosemite Valley. Scientists are rearing frog eggs and turtle hatchlings at the San Francisco Zoo for this release.

Thanks to your support, these mini-but-mighty animals are receiving the best possible protection. With this project, scientists are demonstrating the potential for species recovery in both wilderness and more developed areas.

BLOOMING IN FIRE’S WAKE

SCIENTISTS FIND RARE FLOWERS IN FOOTPRINTS OF WILDFIRES

osemite, which lies within one of the world’s 35 biodiversity “hot spots,” is home to about 1,800 plant species. A small subset of the park’s flora stand out for their unique habitat requirements: They sprout only in the wake of fire. Recent wildfires have created a fleeting window for scientists to study these “fire-following” species before they subside.

In 2015, with support from Conservancy donors, scientists discovered new populations of fire-germinated flowers, including slenderstem monkeyflower, an endangered species that grows only in the Yosemite area. This year, your gifts are allowing scientists to expand their search for ephemeral fire-following plants across a broader range of elevations and habitats. As Student Conservation Association interns gain valuable research experience, visitors are learning about fire’s role in healthy ecosystems through activities including a late May “BloomBlitz.” This event is part of the National Park Service Centennial BioBlitz, a rapid biological survey to inventory diverse species at parks across the country.

RESTORING A TRAIL TO SAVE A MEADOW

“When crew members point out the old trail location to visitors, they are often amazed and grateful.”

— VICTORIA HARTMAN Wilderness Restoration Coordinator

ust south of Tioga Road, the Lyell Fork of the Tuolumne River winds through a sub-alpine meadow, a haven for diverse plants and animals. This idyllic patch of park is also home to a 9-mile section of the John Muir Trail, which attracts a wide variety of visitors, from Tuolumne day-trippers to thru-hikers tackling the 211-mile trek that connects Yosemite Valley and Mt. Whitney.

Throughout the years, the trail’s popularity has started to threaten surrounding habitat. A 2011 study mapped 2.5 miles of ruts created by hikers, horses and mules walking off-trail to avoid water and mud. Ruts disrupt natural hydrology, which can, in turn, alter plant communities and damage habitat for threatened species such as the Yosemite toad and Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frog.

Through a series of Conservancy-supported projects, including one this year, restoration crews have rerouted sections of the trail onto more durable ground, erasing traces of the old trail and restoring meadow habitat by loosening compacted soil and replanting native vegetation.

“Thanks to effective restoration techniques, visitors rarely notice the former trail through the meadow,” notes Victoria Hartman, Yosemite’s wilderness restoration coordinator. “When crew members point out the old trail location to visitors, they are often amazed and grateful.”

By the end of 2016, donor-funded projects will have rerouted 8,900 feet of trail and restored 13.5 acres of wetland. Along the way, crews are surveying for rare plants, educating visitors, enhancing habitat for native amphibians and creating more enjoyable hiking experiences.

September 2015

LEFT The Lyell Canyon section of the 211-mile John Muir Trail follows a fork of the Tuolumne River through a serene Sierra meadow, which is being restored with support from Conservancy donors. ABOVE Crews shifted this stretch of the John Muir Trail in Lyell Canyon, seen above in July 2014, out of the sensitive wet meadow and onto more durable ground. By September 2015, as autumn hues crept into the canyon, the formerly heavily compacted route had been restored to healthy habitat.

Learn more about this year’s work in Lyell Canyon — and other restoration projects you support in the park — online: yosemiteconservancy.org/ your-gifts-work

HONORING THE CENTENNIAL

CELEBRATING THE 100TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

2015 YOSEMITE THEATER SCHEDULE

SUNDAYS : June 26–August 28

Yosemite through the Eyes of a Buffalo Soldier

TUESDAYS : April 12–October 25

Yosemite Search and Rescue

WEDNESDAYS : May 25–October 26

John Muir Series: Conversation with a Tramp

THURSDAYS : May 26–October 27

John Muir Series: The Spirit of John Muir

FRIDAYS : April 8–October 28

Return to Balance: A Climber’s Journey

SATURDAYS : April 9–June 18 & September 3–October 29

Return to Balance: A Climber’s Journey

hen Lee Stetson takes the Yosemite Theater stage, with his long beard and walking stick, it’s easy to imagine you’re back in the late 1800s, gazing up at John Muir. Since 1983, Stetson has brought Muir, the “father of the national parks,” to life for Yosemite audiences.

This season, Stetson stars in The Spirit of John Muir, one of three performances in the Conservancy’s 2016 theater lineup that honor the NPS centennial by connecting visitors with people and events that shaped Yosemite and the broader movement to preserve public lands. In the spring, audiences “met” Galen Clark, Yosemite’s first guardian; this summer, ranger Shelton Johnson will introduce visitors to Buffalo Soldiers, the African-American cavalrymen who served as the park’s early rangers.

Celebrate the centennial by spending an evening with some of the incredible figures who made Yosemite and the park system a reality. See you at the theater!

FROM CAMP 4 TO VALLEY WALLS

ock-climbers flock to Yosemite to challenge themselves on glaciercarved cliffs, following in the rubbersoled steps of countless wall-scaling adventurers. Records of visitors tackling Half Dome date back to the 1870s. But the “golden age” of Yosemite climbing arrived in the 1960s, when pioneering athletes pursued big dreams on some of the world’s biggest walls, shattering ideas about what climbers could achieve.

Photographer and climber Glen Denny, a wellknown figure in Yosemite’s Camp 4, captured the ’60s era in striking black-and-white images. His new Conservancy-published memoir, available in May 2016, recounts challenging climbs, stormy nights on El Capitan, and adventures in and above Camp 4. Through 224 pages of anecdotes and photos, Denny paints a powerful portrait of Yosemite’s vertical landscapes. Thanks to your support for climber-access trails and educational programs, explorers and caretakers of this granite environment are ushering in a new age of world-class climbing and stewardship.

Get a copy of Glen Denny’s memoir for the rock-climber in your life!

Visit yosemiteconservancy.org/store

EXPAND YOUR YOSEMITE HORIZONS

BEYOND BEST-KNOWN EXPERIENCES, ADVENTURE AWAITS

on Miwok-Paiute basketry and American-Indian food preparation. RIGHT The Conservancy’s naturalist-led backpacking trips provide opportunities for beginning and advanced adventurers to explore less-frequented trails and discover Yosemite’s rugged beauty.

ave you snapped a Tunnel View panorama? Strolled through Cook’s Meadow? Hiked to the top of Yosemite Falls? Such classic spots have earned their places at the head of most Yosemite itineraries. Beyond the park’s most popular locales, however, you’ll find thousands of explorationworthy acres alive with biodiversity, history and, of course, breathtaking scenery.

Yosemite Conservancy’s expert-led Outdoor Adventures provide plenty of ways to discover new facets of the park’s natural and cultural landscapes. Start in Yosemite Valley, where you can spend the weekend learning to spot rare songbirds. Or spend

an enjoyable afternoon exploring the park’s American-Indian past through workshops in basket-weaving or native food preparation, led by Julia Parker, a cultural demonstrator often referred to as a “national treasure.”

Summer abounds with opportunities to explore the Yosemite Wilderness. Tuolumne Meadows serves as a starting point for day hikes to little-visited locations, such as Gaylor Lakes, where you might spot American pikas, and Bennettville, a historic mining town amid mountain meadows. For an extended experience, backpack the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne, visit the vanishing Lyell Glacier, or “bag” an impressive peak on Yosemite’s eastern edge.

Ready to find your adventure? Visit yosemiteconservancy.org/outdoor-adventures

OUTDOOR ADVENTURES

Explore the best of Yosemite with a park insider on one of this year’s popular Outdoor Adventures.

2016 OUTDOOR ADVENTURES HIGHLIGHTS

JUNE 3–5

Yosemite Birding: Insiders’ Look

JUNE 18–19 &

SEPTEMBER 23–25

Yosemite Miwok-Paiute Basketry

JUNE 25–26

Learning to Listen: Birding by Ear & Beginning Birding

JULY 16–19 & AUGUST 18–21

High Country Campout for Grown-Ups

AUGUST 5–7

Yosemite Day Hikes: Sierra Nevada Expert Series

AUGUST 6

Survival Scavenger Hunt (great for families)

AUGUST 18–21

Backpack to Lyell Glacier: Last of its Kind

SEPTEMBER 1–4

Backpack to Mono Pass: Peak Bagger

SEPTEMBER 16–17

Yosemite Evening Experiences: Taft Point & Bat Science

OCTOBER 1–2

American-Indian Food Preparation & Acorns

Donor Events & Activities

THE JOHN MUIR HERITAGE SOCIETY

is a community of generous Yosemite Conservancy supporters who have demonstrated a strong commitment to protecting and preserving Yosemite for future generations. With your annual gift of $1,000 or more, you join the influential group of Conservancy donors responsible for the completion of many critical projects in the park each year. Support at this level has tremendous impact, and your leadership gifts enable Yosemite Conservancy to truly make a difference in the park. Join now, and enjoy benefits such as invitations to exclusive events with park staff, an insider’s view of the park, special recognition, and a community of like-minded individuals.

For more information about the John Muir Heritage Society or events, please contact Kim Coull at kcoull@yosemiteconservancy.org or 415-434-8446 x324

Creative Giving & Personal Commitment

The Dornsife family gives their all for Yosemite

hen Dave and Dana Dornsife commit to a cause, they prefer to take an active role to ensure it is fruitful. As donors, campaign chairs and Board members, the Dornsife family has been intimately involved in helping to preserve and protect Yosemite and its wildlife through the Conservancy. Dave explains: “I like the idea of participating actively, to help raise funds, to be good stewards of Yosemite. We only support organizations that accomplish a great deal with the resources available.”

In 1978, Dave moved from Arizona to California, and soon thereafter began a 25-year tradition of weeklong backpacking trips in Yosemite’s high country. During these trips, Dave followed the recommended guidance of hoisting his food into trees — until clever mother bears starting tossing their cubs up to take

“I like the idea of participating actively, to help raise funds, to be good stewards of Yosemite.”

— DAVE DORNSIFE

Yosemite Conservancy Donor

For the

down the food! Dave says, “It was clear we needed a better solution.”

As president and CEO of Herrick Corp., a steel-fabrication company, Dave saw an opportunity to combine his work and personal passion with the creation of new and improved bearproof food lockers in Yosemite. Coordinating with Yosemite Conservancy and Yosemite National Park, Herrick Corp. donated the labor and a substantial amount of the materials to supply nearly 2,000 bear-proof food lockers for Yosemite Valley and at many trailheads leading into the backcountry.

company’s nearly 400 steel workers. He says, “We hear back from them when they visit Yosemite with their families and can proudly point to walkways, bridges or bear-proof food lockers and say, ‘I helped make that happen.’”

The Dornsifes’ creative giving makes it possible to involve many hands in preserving Yosemite. Over the years, Herrick Corp. has given steel for several restoration projects, including bridges at Yosemite Falls, and boardwalks that protect sensitive habitat, including Tenaya Lake and Mariposa Grove. Dave is humbled by the pride of the

Dave’s and Dana’s devotion to Yosemite extends through the family tree. Their daughter and her husband, Kirsten and Dan Miks, are also members of Yosemite Conservancy’s Council. The Dornsifes explain: “Yosemite needs our help to keep it an icon within our national parks. Soon, its stewardship will be in the hands of this generation, to continue preserving the park for our grandkids, and on to the future.”

YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY

Magazine of Yosemite Conservancy, published twice a year.

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Jennifer Miller

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Claire F. Meyler

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Frank Dean

Claire F. Meyler

Eric Ball Design

Linda Mazzu Gretchen Roecker

TradeMark Graphics, Inc.

STAFF :: San Francisco

Frank Dean, President & CEO

Jerry Edelbrock, Vice President, CFO & COO

Kim Coull, Development Director

Edin Draper-Beard, Executive Affairs Manager

Jamie Henion, Events Manager

Debra Holcomb, Planned Giving Director

Sara Jones, Institutional Giving Officer

Holly Kuehn, Development & Donor Services Assistant

Isabelle Luebbers, Annual Giving Director

Claire F. Meyler, Communications Manager & Webmaster

Jennifer Miller, Marketing & Communications Director

Eryn Roberts, Data Entry Assistant

Gretchen Roecker, Communications & Social Media Manager

Amanda Roque, Data Services Assistant

Jonathan Roybal, Major Gifts Officer

Kit Thomas, Controller

STAFF :: Yosemite

Adonia Ripple, General Manager of Yosemite Operations

Aline Allen, Art Center Coordinator

Greg Archer, Valley Sales Supervisor

Nicole Brocchini, Museum Store Supervisor

Kylie Chappell, Outdoor Adventures Coordinator

Melissa Cosgrove, Lead Wilderness Reservation Assistant

Pete Devine, Resident Naturalist

Teresa Ellis, Sales Information Assistant

Schuyler Greenleaf, Projects Director

Suzy Hasty, Volunteer Program Manager

Cory Jacobs, Inventory Coordinator

Ryan Kelly, Projects Coordinator

Michelle Kuchta, Accounting Assistant

Olotumi Laizer, Valley Complex Supervisor

Katie Manion, Retail Operations Manager

Cassie May, Outreach & Wholesale Coordinator

Michael Ross, Naturalist

Angela Sberna, Accounting Director

Mark Scrimenti, Wilderness Reservation Assistant

Shelly Stephens, Inventory Manager

Laurie Stowe, Wilderness Programs Manager

STAFF :: Southern California & National

Patti Johns Eisenberg, Major Gifts Officer

Spring.Summer 2016 :: Volume 07. Issue 01 © 2016

Federal Tax Identification No. 94-3058041

Ways to Give

THERE ARE MANY WAYS you and your organization can support the meaningful work of Yosemite Conservancy. We look forward to exploring these philanthropic opportunities with you.

CONTACT US

Visit yosemiteconservancy.org

Email info@yosemiteconservancy.org

Phone 415-434-1782

INDIVIDUAL GIVING

Development Director

Kim Coull kcoull@yosemiteconservancy.org 415-434-8446 x324

Annual Giving

Isabelle Luebbers iluebbers@yosemiteconservancy.org 415-434-8446 x313

Major Gifts – Northern California Jonathan Roybal jroybal@yosemiteconservancy.org 415-434-8446 x318

Major Gifts – Southern California Patti Johns Eisenberg peisenberg@yosemiteconservancy.org 626-792-9626

FOUNDATIONS

& CORPORATIONS

Sara Jones sjones@yosemiteconservancy.org 415-434-8446 x328

PLANNED GIVING & BEQUESTS

Debra Holcomb dholcomb@yosemiteconservancy.org 415-434-8446 x319

Yosemite Conservancy 101 Montgomery Street, Suite 1700 San Francisco, CA 94104 Fax 415-434-0745

HONOR & MEMORIAL GIFTS

Isabelle Luebbers iluebbers@yosemiteconservancy.org 415-434-8446 x313

GIFTS OF STOCK

Amanda Roque stock@yosemiteconservancy.org 415-434-8446 x330

SEQUOIA SOCIETY MONTHLY GIVING

Isabelle Luebbers iluebbers@yosemiteconservancy.org 415-434-8446 x313

MATCHING GIFTS

Isabelle Luebbers iluebbers@yosemiteconservancy.org 415-434-8446 x313

VOLUNTEER OPPORTUNITIES

Suzy Hasty shasty@yosemiteconservancy.org 209-379-2317 yosemiteconservancy.org/volunteer

Yosemite Conservancy

101 Montgomery Street, Suite 1700

San Francisco, CA 94104

Yosemite’s natural wonders are not only our inheritance, but also our responsibility. Your legacy gift to Yosemite Conservancy makes a lasting impact beyond your lifetime, commemorating your special connection to Yosemite while ensuring the park remains a beloved treasure for future generations to enjoy.

To find out how you can leave your legacy to Yosemite, contact Debra Holcomb at dholcomb@yosemiteconservancy.org or 415-434-8446 x319. yosemiteconservancy.org