Destinations West

Destinations West

Dear Friends,

The West is often referred to as though itʼs a kind of mythological place, but for many of us—and I believe that includes the artists—the West is real. And it is this sense of “realness,” an authenticity, that is precisely the source of the attraction, where human experience seems closer to nature. It is true, the West has represented tremendous hardships. Even so, it has also yielded countless rewards, offering landscapes of stunning beauty, vibrant skies, quiet spots for inspiration, as well as a place that people want to call home. For all these reasons, I am pleased to share with you our 2024 catalogue, Destinations West , a comprehensive selection of the genre from the earliest explorers to almost our present day.

At one time, the “Far West” and its numerous Native inhabitants were largely unknown to the American public east of the Mississippi River. Explorations were mostly limited to trappers and fur traders, and government research teams. But in the early 1830s, two intrepid artists, George Catlin and Karl Bodmer, completed their own arduous treks along thousands of miles of the Missouri River. In doing so, they memorialized the Native people in their homelands for the rest of history. We are honored to be presenting examples of these rare works.

Another unique offering is a set of watercolor drawings by Levi Rinehart, a young captain in the U.S. Army who, in the 1860s, depicted scenes from his posts along the North Platte River to Fort Laramie (detail at left). Weʼre also featuring works by Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran, for whom the beauty of the Far West was well worth the challenging expeditions to the Rocky Mountains and the Southwest. Bierstadtʼs first trip was in 1859 and Moran began his travels in 1871. Afterward, each artist rose to

fame by creating exceptional compositions on canvas and paper based on their eyewitness accounts of the West.

Similarly, Edward S. Curtis devised the enormous goal of documenting, for posterity, all the Native American tribes west of the Mississippi. With earnest appreciation for their cultures, his artful photographic and ethnographic work spanned over thirty years. Inside, youʼll see two of his highly prized images in goldtone format.

As time went on, diverse artists had become enchanted by the idea of working in the American Southwest and, in particular, Taos and Santa Fe. For Destinations West , weʼre showcasing works by some of the most noteworthy, including W.R. Leigh, Robert Henri, Alexandre Hogue, Joseph Henry Sharp, Bert Phillips, Ernest Blumenschein, Victor Higgins, Gustave Baumann, and Thomas Hart Benton, whose painting appears on the cover. In addition, youʼll see the works of more recent stellar artists such as Fritz Scholder, John Nieto, and sculptor Allan Houser.

As you can see, while its lands and people are no longer such a mystery, the West has not lost its powerful draw. Perhaps Thomas Hart Benton described it best in his memoir: “In the West proper there are no limits. The world goes on indefinitely… you feel actually within yourself the boundlessness of the world.” That, in a word, is inspiration.

I hope you will enjoy the artwork on these pages, and please stop by the gallery the next time you are in Santa Fe. We look forward to seeing you!

Richard Lampert, June 2024

Thomas Moran 1837–1926

On his way to the Yellowstone region, Thomas Moran stopped in Green River, Wyoming, where the scenery inspired his first sketches in the West.

“In 1871 Moran did not linger in Green River. He was on his way to join Hayden’s survey party in Montana. . . . Before leaving Green River, however, he did secure a number of sketches of Citadel and Castle Rocks—the enormous buttes that dwarfed the burgeoning town below—and these he put to very good use, later, when he returned east. . . . The multicolored, castellated buttes were an entirely fresh subject for paintings. Moran made the most of this opportunity, claiming the landscape as his own through a series of paintings completed over a period of forty years.”

– Nancy K. Anderson, “Thomas Moran”

“After a five-year absence, he accepted a commission from the Union Pacific Railroad in 1879 and set out West with his brother Peter. They spent most of the month of August in Nevada, Utah, and Idaho, and completed the journey with a view of the Teton Range. . . . Thomas and Peter crossed the Green River on their way home in September, and Thomas painted about a dozen watercolors of the colorful cliffs he had admired and sketched on his first trip [with the Hayden survey expedition, 1871]. They proved to be a lasting motif, one with imagery freshly renewed on almost every western journey. Their similarity provided a basis around which the artist painted the variety of atmospheric and coloristic effects the scenery offered. They became for Moran a rite of passage to the West.”

– Carol Clark, “Thomas Moran: Watercolors of the American West”

George Catlin 1796–1872

"Beyond Catlinʼs place as an artist and writer and provoker of a national conscience, he must be summarily recognized as one of America's greatest visionaries. . . . He produced the grandest scheme for cultural preservation and individual artistic expression ever conceived in this nation.”

– Peter H. Hassrick, Introduction to “Drawings of the North American Indians,” by George Catlin

George Catlin 1796–1872

This Page

Crow, Bi-Eets-E-Cure c. 1852

Graphite on paper

14 x 10 1/2 inches

Opposite Page

Crow, Chah-Ee-Chopes c. 1852

Graphite on paper

14 x 10 1/2 inches

of Bisons c. 1840 Hand-colored aquatint line engraving 14 x 17 inches

"Bierstadtʼs many oil sketches and surviving sketchbook from his first trip west [1859] reveal an early interest in the region's Native cultures and unique fauna, in addition to its impressive geography. The artist was not myopically focused on the landscape; rather, he picked up the mantle of earlier artist-explorers, creating sensitive studies and portraits of American Indians and western wildlife, especially buffalo.”

– Karen B. McWhorter, “Albert Bierstadt: Witness to a Changing West”

Captain Levi Rinehart 1836–1865

Amember of the 11th Regiment, Ohio Volunteer Cavalry, Captain Levi Rinehart was ordered to the American Far West in April of 1862. First dispatched to Fort Leavenworth, the troops then moved onward to Fort Laramie, arriving on May 30th. Responsible for protecting various locations along the North Platte River, including the Overland Mail route, telegraph stations, and other American encampments, the troops found themselves engaged in numerous skirmishes with Native American tribes. “The Eleventh Ohio was sorely tested during the winter of 1864. On November 28, Colonel John M. Chivington led Colorado volunteers in an attack on a large Indian camp at Sand Creek, Colorado. This infamous assault sparked a general uprising that would spread across the Central Plains. . . . Trouble began on February 13, when Captain Rinehart left Deer Creek [Station] with ten men to pursue Cheyennes who had raided a prospectorʼs camp. The soldiers intercepted the Indians near La Prele Creek, and in a brief skirmish Rinehart was killed.” He was 29.

“Despite Indian hostilities, life for the Eleventh Ohio generally consisted of monotonous routine, especially at the scattered stage stations. . . . Recreation consisted mainly of reading and hunting.” Fortunately, Levi Rinehart used some of his free time to create lasting visual documents showing those critical locations during an extremely tumultuous time. Eight of his works have been documented, three of which were returned to his family with his “effects.” The watercolor scenes displayed on these pages are the remaining group of five that, remarkably, have survived.

Quotations from: David P. Robrock, “The Eleventh Ohio Volunteer Cavalry on the Central Plains, 1862-1866”

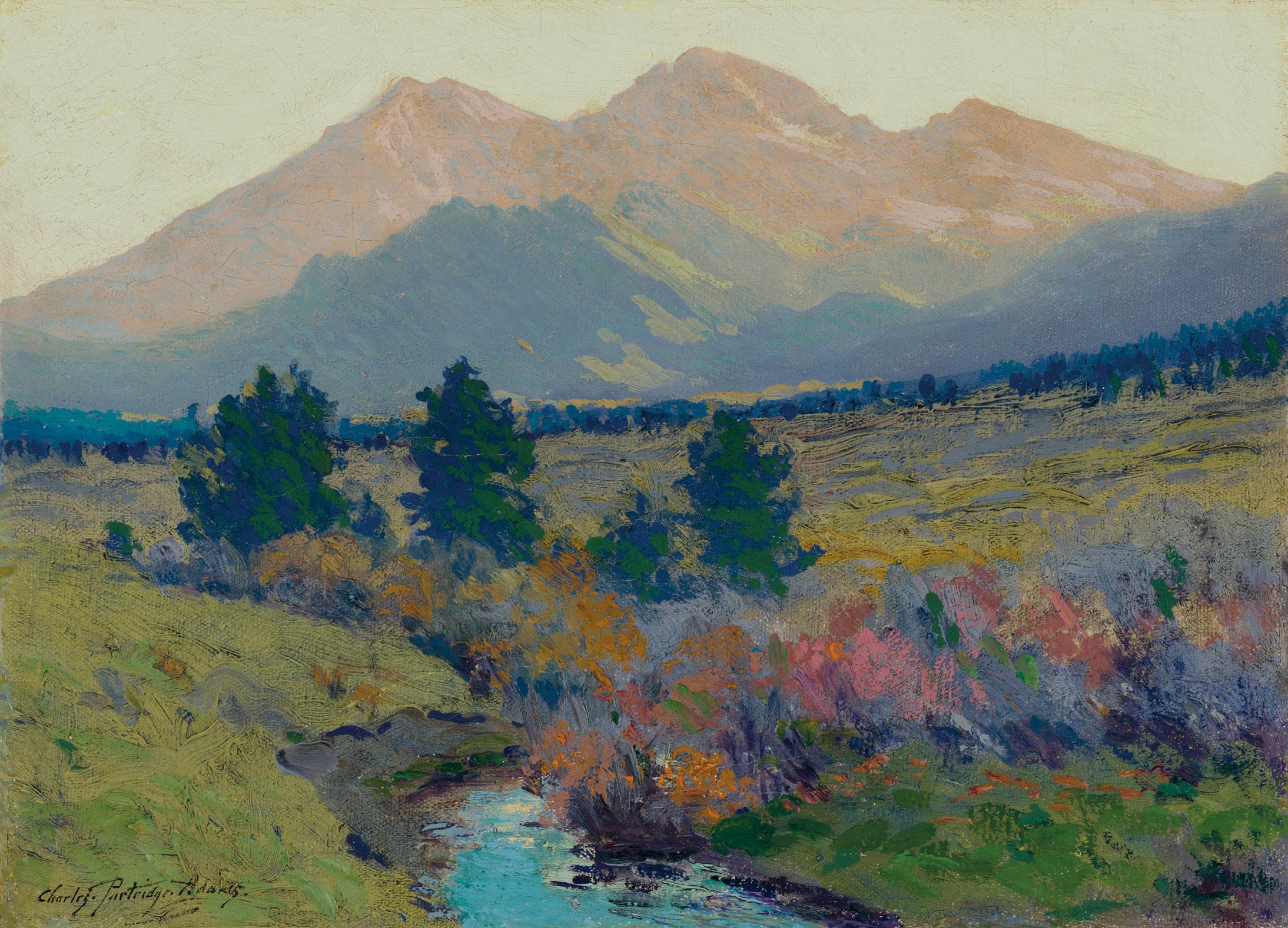

Charles Partridge Adams 1858–1942

9 x 6 inches

Signed lower right

Robert Henri 1865–1929

and gouache on paper 8 1/4 x 10 1/ 2 inches Signed lower right

and gouache on paper 10 3/ 8 x 8 inches Signed lower left

William R. Leigh 1866–1955

Edward S. Curtis 1868–1952

“I n the early morning this boy, as if springing from the earth itself, came to the authorʼs desert camp. Indeed, he seemed a part of the very desert. His eyes bespeak all of the curiosity, all of the wonder.” –Edward Curtis, “The North American Indian,” Portfolio 1

Bert G. Phillips 1868–1956

Study for The Lost Trail c. 1918-1919 Oil on board 8 x 10 inches Signed lower right

Ernest L. Blumenschein 1874–1960

Blumenschein fell in love with Taos on his very first visit, with Bert Phillips, in 1898. From those early days until his last, he searched for the words to describe the emotions he derived from the countryside and its Pueblo and Hispano communities. His paintings offer, perhaps, an even higher plane of that expression, achieving what he hoped would be viewed as uniquely American art. As a 1926 Washington Post reviewer wrote: Blumenschein was “working for what the artists are pleased to call the third dimension. . . . this comes from the mind of the artist . . . seeking to paint this thing that is beyond the mere surface quality.”

During his preparation of “Jury for the Trial of a Sheepherder for Murder,” Blumenschein devised the entire composition in a mixed media study on paper — the work we are presenting. Subsequently, Blumenscheinʼs 1936 “Jury” painting, an oil on canvas, received considerable national attention and won a prestigious award in 1938. Since then, it has been displayed in over twenty-five exhibitions nationwide and is now in the collection of the Rockwell Museum, Corning, New York. Widely considered one of Blumenschein's most significant works, his mixed media study is integral to that celebrated history.

“Blumenschein attended the actual trial in 1934, a year before he began work on the composition; he changed the background from the Taos courthouse to his own studio and used one model, a Spanish-Mexican laborer, for all the figures. Although the heads were executed from memory of mountain types of Northern New Mexico, the individual characterization is so literal that the spectator is tempted to construct a case history for each member of the jury.”

– Art News, September, 1947

Jury for the Trial of a Sheepherder for Murder c. 1936 Mixed media on paper 11 x 7 1/4 inches Signed lower left

Victor Higgins 1884–1949

Victor Higgins made a painting sojourn to Taos in 1914, and the next year the Museum of New Mexico hosted his first one-man show at the Palace of the Governors. Becoming a regular in Taos, he joined the Taos Society of Artists in 1917. Considered the most artistically progressive of the group, Higgins’ work was recognized with many notable awards and featured in important museum and gallery exhibitions.

“An earmark of Higginsʼ early still lifes from this period is the quality of his brushstroke. He did not attempt to disguise, but rather emphasize, his brushwork.”

– Dean Porter, “Victor Higgins: An American Master”

"T he emotional and romantic quality which colors Ellisʼ attitude toward life is very evident in his painting. From the beginning he responded to the southwestern landscape with an intense love, and his forceful works have always shown a direct response to a particular place and a particular time.”

– Edna Robertson and Sarah Nestor, "Artists of the Canyons and Caminos"

Thomas Hart Benton 1889–1975

Preeminent among American artists, Thomas Hart Benton is closely associated with midwestern regionalism. Yet, early in his career, he was active with the avante-garde Synchromists, whose abstract works were based on high-keyed color relationships. By the 1920s, he turned to realism and developed his signature style—figurative compositions displaying a powerful command of color and form. With this painting style, which often conveyed a narrative structure, Benton was rewarded significant popular acclaim.

“In the West proper there are no limits. The world goes on indefinitely. … The Rocky Mountains rise in such a way, tier behind tier, that they carry your vision on and on, so that the forward strain of the eyes is communicated to all the muscles of the body and you feel actually within yourself the boundlessness of the world. You feel that you can keep moving forever without coming to any end. This is the physical effect of the West.”

– Thomas Hart Benton, “An Artist in America”

Cady Wells 1904–1954

"Wells’ choice of watercolor as a medium was perfectly suited to his restless, intuitive, emotional temperament, and his need to be physically engaged with the materials he worked with. Watercolor demands both decisiveness and spontaneity. It creates a transparent luminosity through which light is reflected from the surface of the paper and layers of color washes.” – Lois Rudnick, "Cady Wells and Southwestern Modernism"

Allan Houser 1914–1994

"Realism, naturalism, stylized figurative abstraction, and abstract-surreal experiment are among Houserʼs multiple modalities, all closely related to earth forms and traditional Indian images. Sequential growth and change in themes have continued to occur spontaneously, without apparent conscious plan.”

– Barbara H. Perlman, “Allan Houser (Ha-o-zous)”

This Page

Statesman of the Plains 1988

Bronze No. 5 of 5

78 x 27 x 28 inches

Inscribed in bronze near base

Opposite Page

Midnight Lullaby 1987

Bronze No. 18 of 20

19 1/2 x 17 1/2 x 9 1/2 inches

Inscribed in bronze on back

Born to a Mescalero Apache mother and Hispano father, John Nieto envisioned himself an artist from a very early age. After graduating from college, he completed a stint in the Army working as an illustrator. Overseas, he spent time in Paris where he studied the artwork at the Louvre Museum, becoming particularly moved by the emotionally charged color treatment of the modernist Fauve movement. In the U.S., he returned home to his family roots, ready to follow his calling, depicting subjects meaningful to his life.

“John Nieto has always brought a contemporary eye to classic western motifs. Whether portraying Native Americans or animals, his dramatic, often electric canvases make the viewer sit up and take notice. Nieto maintains that his art ʻis more the result of an emotional involvement with my subject matter than a cerebral one.ʼ” – Bonnie Gangelhoff, Southwest Art , January, 1970

Fritz

651

©2024 Zaplin | Lampert Gallery

Designer Alex Hanna, Invisible City Designs

Writer Stacia Lewandowski

Photographer Jamie Hart

Color Separations

Andy Johnson, Underexposed Studios

505.982.6100 zaplinlampert.com