13 minute read

INTRODUCTION

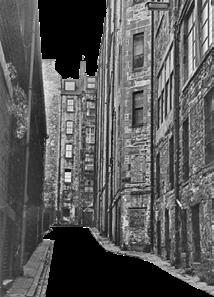

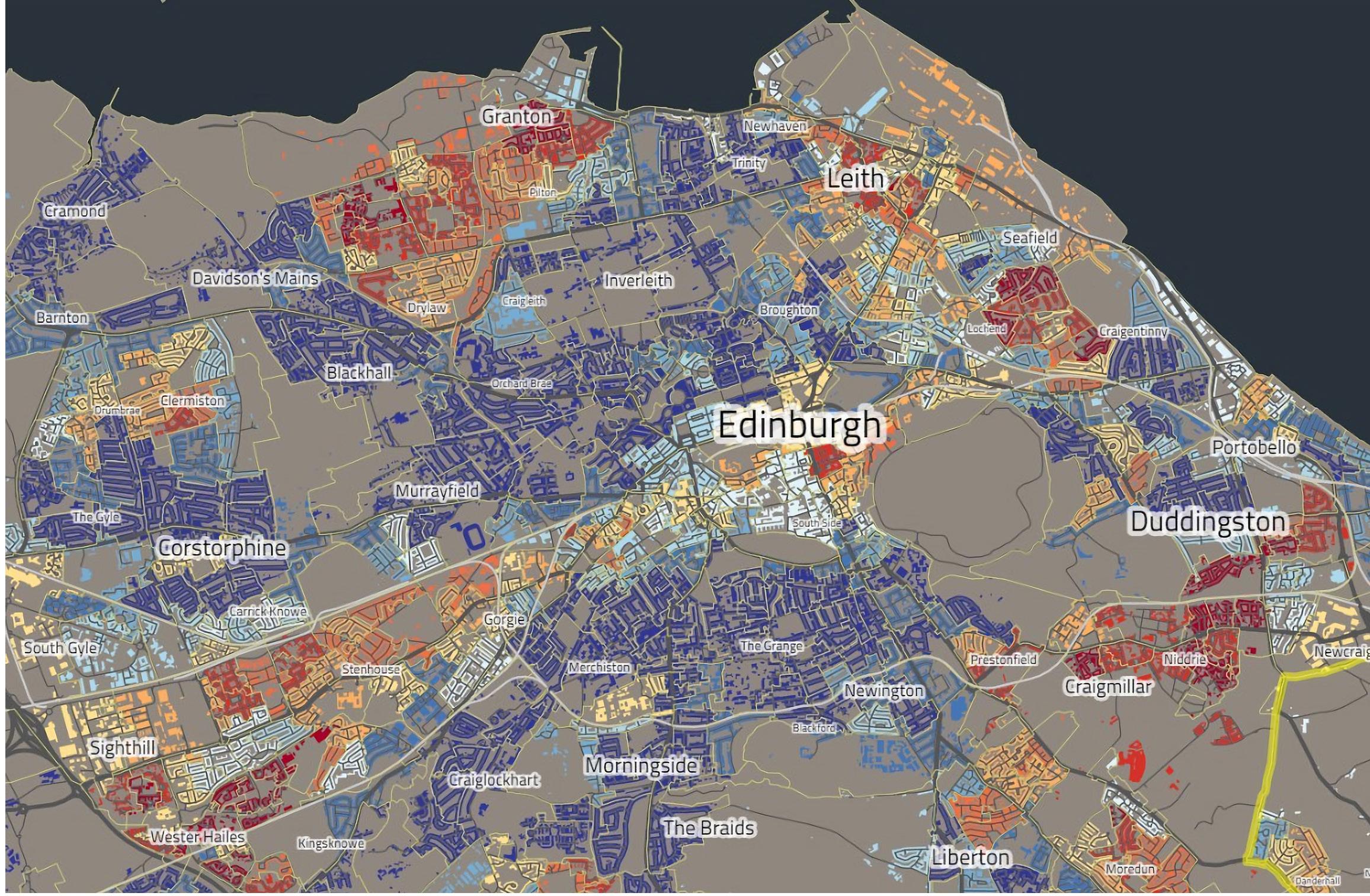

Hundreds years ago, due to Edinburgh’s horrible environment (people who lived here put waste and effluence on the Nor’ Loch, which today is the site of the Princes Street Gardens) , therefore the citizens gave Edinburgh a nickname, which is called Auld Reekie. Under this horrible circumstance, rich people decided to build a new town and start a new life with old town remain unchanged. As for normal people, they still had to tolerate the smelly air and inconvenient facilities. To be specific, some of them even lived in the vaults of South Bridge, inside which there was no sunlight and fresh air. The new town and old town gradually became quite different two tales of the city, which only connected by bridges.

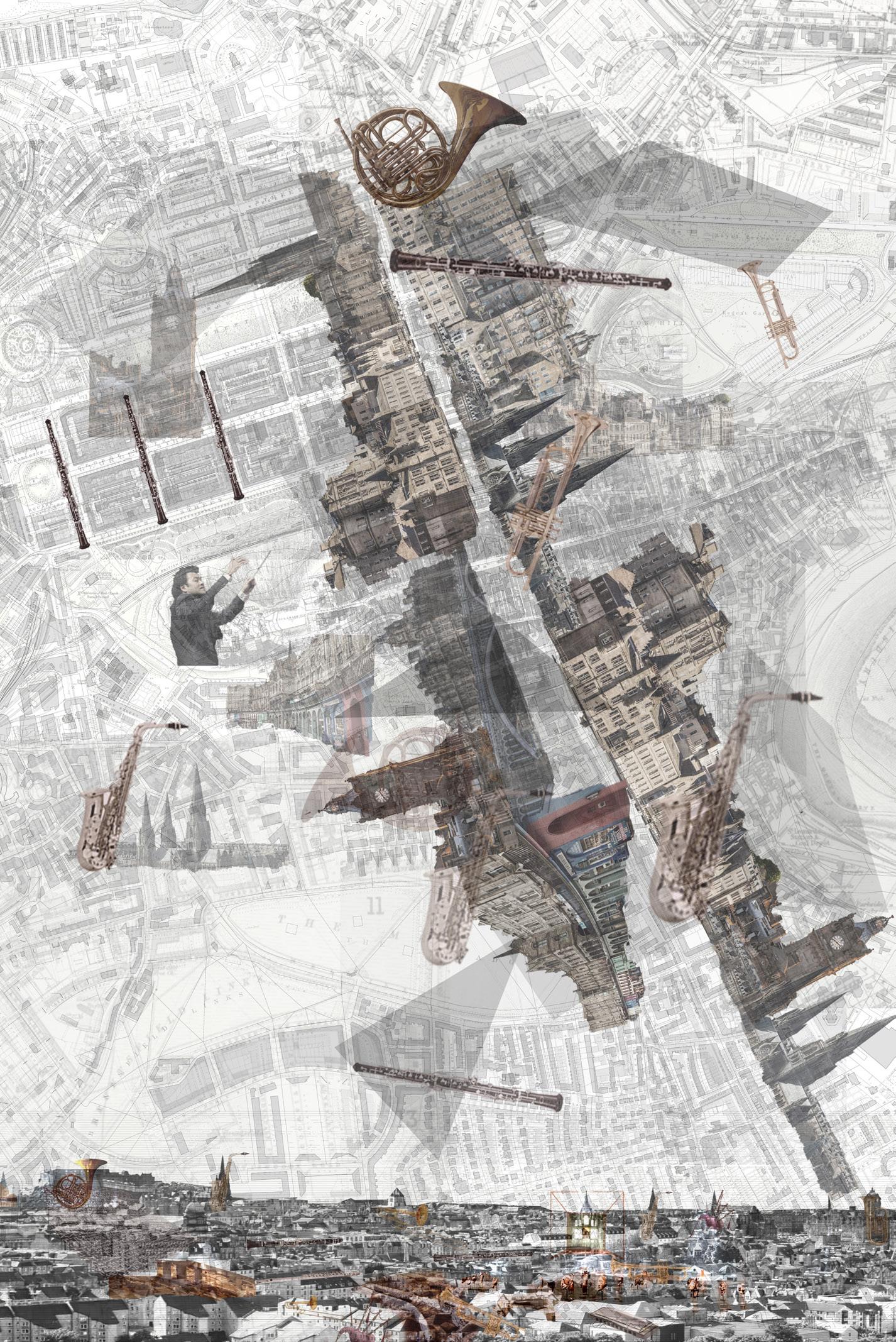

In March 1967, Michel Foucault gave a speech which topic is Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias, and during the speech, he talked about the definition and understanding of heterotopia. Based on Foucault’s theory, David Grahame Shane promoted more his understanding about heterotopia on his book Recombinant Urbanism. In his opinion, he thought heterotopia plays a vital role in a city, not only can it mirror and reflect the process of the development of the city, but also it can influence and change city as well.3 According to the feature of heterotopia, this essay will talk about the possibility about making South Bridge, where is site of the design, become a “boat” heterotopia, which is Foucault’s favorite type of heterotopia, by bringing wind and Caledonian Forest to South Bridge. In that case, not only can it improve the environmental condition, but also it can link and connect social, human and environment.

Advertisement

CHAPTER 1 [Wandering in South Bridge]

1.1 Prosperity and Decline

1.2 Frozen Space

1.3 Hidden Conflict

On stair wi tub or pat in hand

The bare-foot housemaid loe to stand

Auld Reekie will at morning smell

Then with an inundation big as

The burn that ‘neath the Nor Loch brig is They kindly shower Edina’s reses

To quicken and regale our noses.4

1.1 Prosperity and Decline

When we walk through the streets of Edinburgh, we can't help but marvel at how well the city has combined history and modernity: old buildings brought back to life by the introduction of new businesses; modern facilities that make the city work more smoothly; and historical monuments that silently record the city's constant changes.

But the city was far less decent a few hundred years ago than it is today. In Edinburgh the rocky strata of the foundation precluded wit “lurgies” containing household excrement of every kind. A municipal ordinance directed that at ten o’clock in the evening these receptacles should be emptied into the street below. Accordingly, at the appointed hour, the entire malodorous collection was thrown out from all windows to the accompaniment of the historic cry “gardy loo”, and the agonized shrieks of “Haud your hand!” from the unlucky pedestrians who happened to be passing at that moment.5

1.1 Prosperity and Decline

Due to the defensive nature of the city and its geographical location, Edinburgh has built a large number of walls around the Old Town. however, the defensive walls built round what is more or less the Old Town served less their original purpose than to cram a rapidly increasing population into the tall tenements that were, right up to our own century, to be a byword for noisome living. In such conditions street violence was almost inevitable and the upper classes as well as the lower were noisy brawlers.7 The numerous chimneys in the flats emitted a huge amount of smoke, which greatly damaged the air quality of the city, and as the population grew, the fumes and smoke became even more intense. In response to this situation, people chose to discharge their filth into the Nor’ Loch, but this did not solve the problem at all and the stench and smoke continued to fill the city. Over time, Edinburgh was nicknamed 'Auld Reekie'.

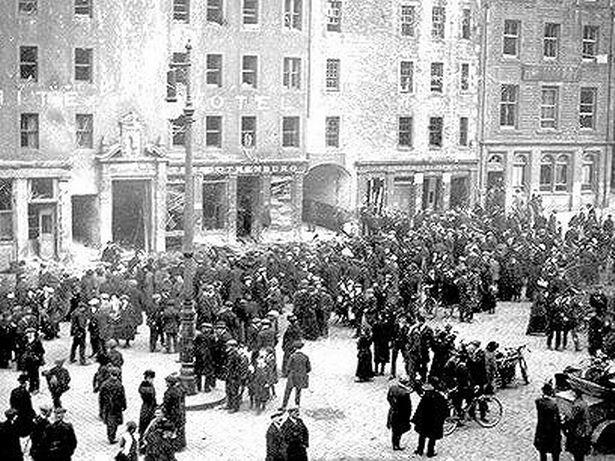

In order to get rid of this nickname for the 'Athens of the North', urban planners decided to build a new city to revive the city's appearance. In the planning of the new city, the planners learnt from the lessons of the old city and eventually a new city with spacious streets and no more dense buildings emerged. However, the new city was not made for all the people. The rich left the crowded and dirty old city and moved to the open new city to the north, leaving a large number of poor people still living in the old city. The new city and the old city were no longer just separated by space, but by a physical and cultural divide between classes.

1.1 Prosperity and Decline

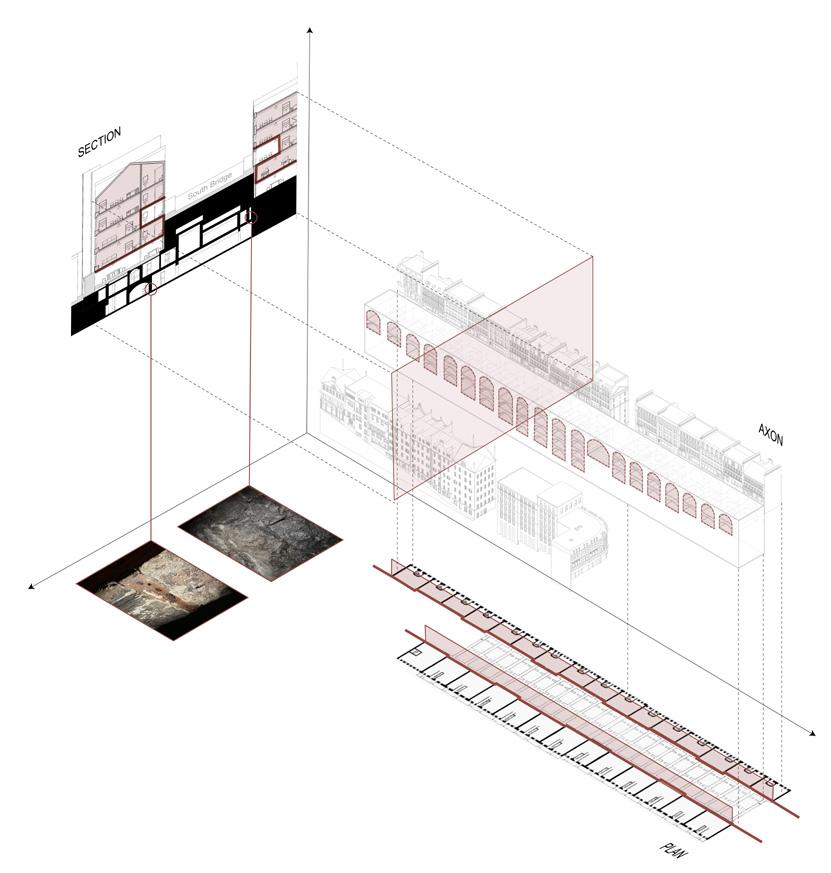

When talking about the development of the city of Edinburgh, South Bridge is a necessary part of the discussion

When Robert Adams, the father of Edinburgh, returned from Rome to Edinburgh, he wanted the nobility to have a decent Roman life. So he built the South Bridge to allow the nobility to walk on the bridge and show off their wealth while moving smoothly between the New Town and the Old Town. The cost of building the South Bridge was undoubtedly a huge expense for the government. In order to relieve the financial pressure, the government decided to build buildings on both sides of the South Bridge for commercial activities and to use the inner arches of the South Bridge as commercial premises to make more profit. During this period, a variety of businesses sprang up inside the South Bridge: bars, crafts, manufacturing...

1.1 Prosperity and Decline

The South Bridge was originally built to link the New Town with the Old Town, to facilitate the smooth development of the city as a whole and to form an organic whole for Edinburgh, and was certainly a manifestation of a national urbanism in its purpose.

Like its sister, the North Bridge, the South Bridge was built as a result of a rational urbanism: the use of the arched structure minimises the loss of materials, while the arch structure allows for a large span and a surplus of space that can be developed for secondary use. The choice of structure, the construction and the use of space all reflect the rational thinking of the designers.

1.1 Prosperity and Decline

The completion of the South Bridge was a great boon to the city of Edinburgh, but the result was an irrational urbanism: the South Bridge was originally built to allow the aristocracy to walk around and show off their wealth, and in order to recover the cost of building the bridge, the choice was made to build buildings on both sides of the bridge for commercial purposes, and to develop commercial activities inside the bridge as well. The same commercial activities were carried out inside the bridge. The bridge was not designed and built with the quality of life of the people who used and lived in it in mind, but rather with a view to maximising commercial profitability, and it was abandoned and lost to history because of its internal environment, structural problems and historical background.

The process of designing a city should be holistic and multifaceted, and every decision made needs to take into account the potential impacts that will follow, as each part of the city is closely related to the others, and we cannot be held hostage by a particular interest group at the expense of the experience of others. as Ross E. Adams said that "as I try to show, constituted by a patchwork of ideas, diagrams, truths and remnants composed by both ancient and contemporaneous histories alike."8

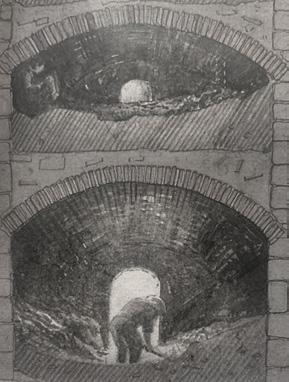

At the environmental level, Southbridge reveals a number of problems while mirroring the neglect of the city as a whole at the environmental level. The interior of the South Bridge suffers from three main environmental problems: light, wind and water. As Luce Irigaray and Michael Marder suggested "No doubt, air is the most essential element to terrestrial life, and it is also the element that has the greatest power to ensure a mediation between the different states of matter, within us and outside of us."9 However, the enclosed nature of the building means that air cannot always circulate inside, which means that dirt and all kinds of waste accumulate inside. And because it was not built to be watertight, dirt from the roads and rainwater (Edinburgh happens to be a rainy city) all penetrated the South Bridge. These three problems do not exist in isolation, but rather they are interrelated and interact with each other: the closed environment prevents the circulation of air, which in turn prevents the exhaust air and water from draining out of the interior, while the absence of sunlight does not reduce the humidity and temperature of the interior. The three elements work together in a vicious circle, leading to a constant deterioration of the environment. It is no exaggeration to say that the whole building has stopped breathing and that the building is nothing more than a pile of decomposing chaos. 10

1.2 Frozen Space South Brdge analysis

9 Luce Irigaray and Michael Marder, Through Vegetal Being : Two Philosophical Perspectives (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016), 24.

10 Emanuele Coccia and Dylan J Montanari, The Life of Plants : A Metaphysics of Mixture (Cambridge, Uk ; Medford, Ma: Polity Press, 2019).41.

The increasing deterioration of human relations with the socius, the psyche and 'nature', is due not only to environmental and objective pollution but is also the result of a certain incomprehension and fatalistic passivity towards these issues as a whole, among both individuals and governments.11 Therefore, in looking at and addressing the problem, we should consider the environment, social relations and the people themselves at the same time. But this does not mean that we should force it back to the way it was, or even that it would be irrational to do so. As Félix Guattari says: " Of course, it would be absurd to want to return to the past in order to reconstruct former ways of living.”12

11 Félix Guattari. 2000. The Three Ecologies Translated by Ian Pindar and Paul Sutton. New York: Athlone Press.p.41.

12 Félix Guattari. 2000. The Three Ecologies Translated by Ian Pindar and Paul Sutton. New York: Athlone Press.p.42.

Janet Abu-Lughod propoesd that "The major metropolis of almost every newly industrialized country is not a unified city, but in fact two entirely different cities, physically juxtaposed, but architecturally and socially distinct."13 This is evident in Southbridge: two groups of people living in almost the same spatial coordinate system, but leading different lives, living in close proximity to each other, but with vastly different living conditions and quality of life. This is also evident in the Close: on the map, the poor and the aristocrats live in exactly the same coordinates, but in reality they have a completely different experience: at night the aristocrats dump their excrement through the windows, while the poor are forced to endure the pungent smell and the dirty filth. When the city planners were faced with this situation, they did not consider how to solve these problems, but rather how to transform the city from the perspective of protecting the rich. As a result, Edinburgh has grown considerably, but the changes have not been very relevant to the people in crisis and drifting heterotopia, but have further pushed them to the margins of the city (through exorbitant prices and rents).

CHAPTER 2 [Heterotopic Chimney]

2.1 What's heterotopic chimney

2.2 Why heterotopic chimney

2.3 What kind of heterotopic chimney

Once, a city was divided in two parts. One part became the Good Half, the other part the Bad Half.

The inhabitants of the Bad Half began to flock to the good part of the divided city, rapidly swelling into an urban exodus.

If this situation had been allowed to continue forever, the population of the Good Half would have doubled, while the Bad Half would have turned into a ghost town.

After all attempts to interrupt this undesirable migration had failed, the authorities of the bad part made desperate and savage use of architecture: they built a wall around the good part of the city, making it completely inaccessible to their subjects.15

2.1 What's heterotopic chimney

In March 1967, in a speech entitled Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias, Foucault explained heterotopia as follows: The heterotopia is capable of juxtaposing in a single real place several spaces, several sites that are in themselves incompatible. Heterotopias are most often linked to slices in time—which is to say that they open onto what might be termed, for the sake of symmetry, heterochronies.16 This interpretation clearly illustrates the specificity of the heterotopia, in that Foucault chooses particular spaces, particular 'places' with a 'connecting' function that connects all other 'places'. These places are specific relational places and relational spaces.17 Southbridge has a strong need for this characteristic of heterotopia: the multiple buildings and their systems are closely interdependent on a spatial level, but currently not strongly related to each other, leading to a fragmentation on different levels.

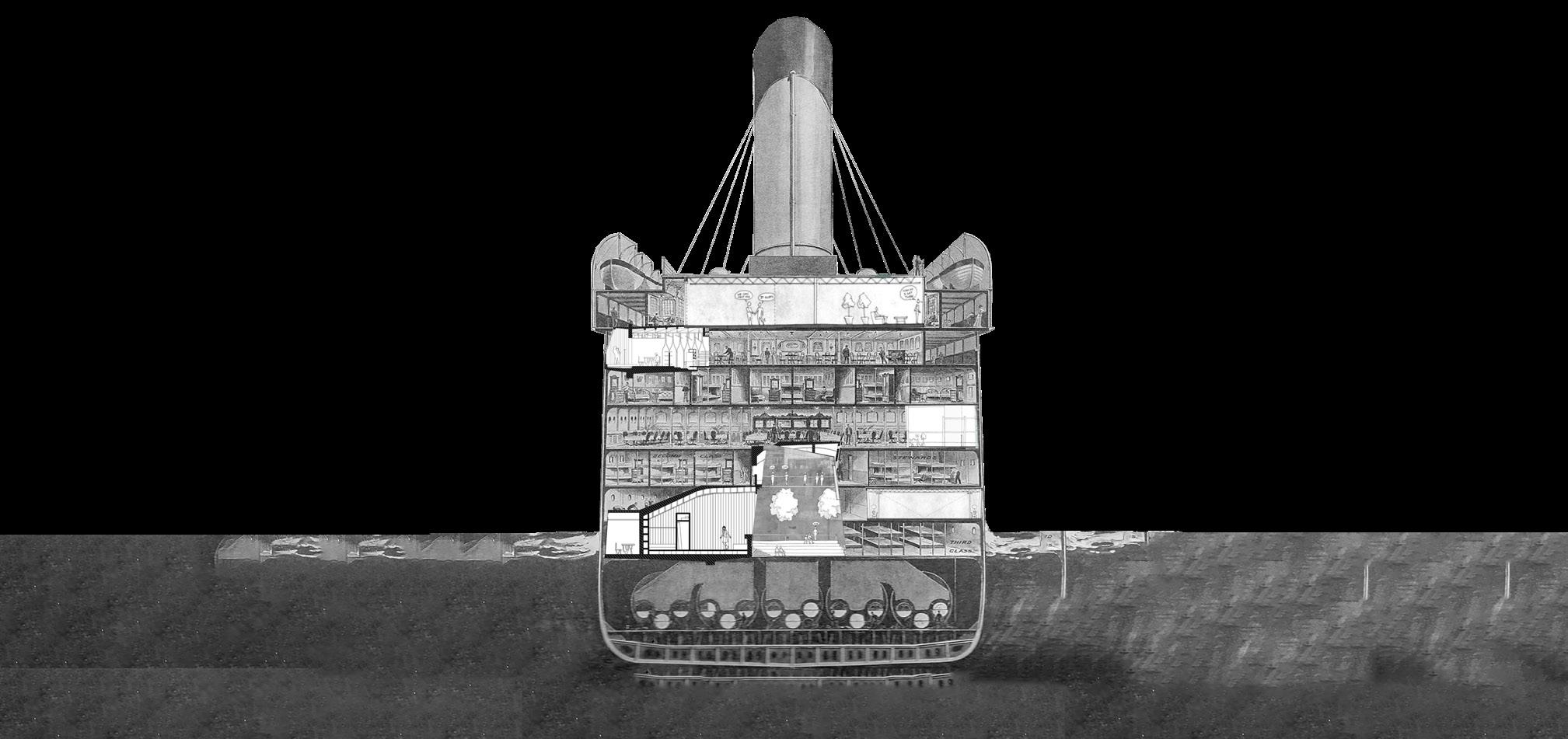

In the course of his speech, Foucault spoke highly of the ship heterotopia, he said: "The ship is the heterotopia par excellence."18 The reason for this is that the ship itself, as a space without a definite location, wanders between spaces with completely different properties that make a connection with each other.

Based on the characteristics of the South Bridge itself: is it possible to design a heterotopia in the South Bridge where people can experience different states of independent space? Based on the historical properties of the South Bridge itself, and the fact that its own traces are a record of time changes, can it be a time travelling heterotopia? These two points are design expectations based on Foucault's theory of heterotopia, but they do not respond to the problem of the fragmentation of the environment, social relations and people themselves, which is so important for Nanqiao and the city as a whole. The resulting heterotopia therefore needs to be ecological in its own right, and to have a positive impact on other spaces through its connection to them, and ultimately on the people who live in them. Such a heterotopia is the right kind of heterotopia for Southbridge and for Edinburgh.

16 Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” Diacritics 16, no. 1 (1986): 25, https://doi. org/10.2307/464648.

17 张锦 . Jin Zhang. 2016. 福柯的 " 异托邦 " 思想研究 = a Study of Michel Foucault’s Ideas of “Heterotopias” / Fu Ke De"Yi Tuo Bang"Si Xiang Yan Jiu = a Study of Michel Foucault’s Ideas of “Heterotopias.” 北京大学出版社 , Beijing: Bei Jing Da Xue Chu Ban She.pp.127

18 Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” Diacritics 16, no. 1 (1986): 29, https://doi. org/10.2307/464648. Boat heterotopia

2.1 What's heterotopic chimney

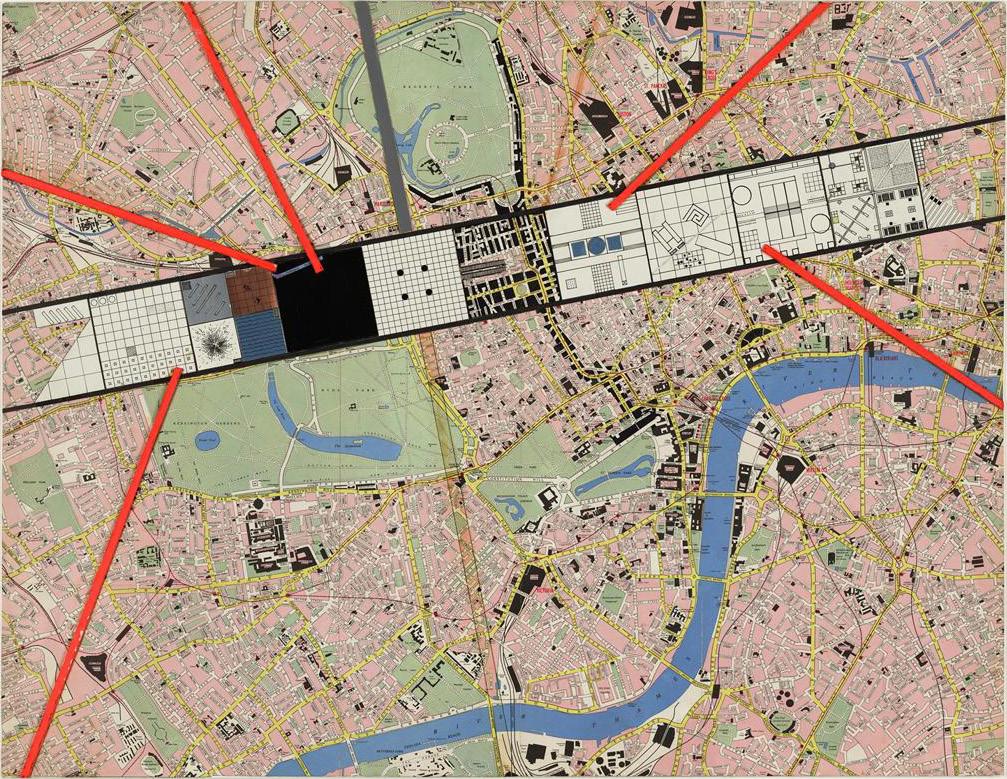

In 1972, Koolhaas also chose to respond to the problem of the great fragmentation of the city by using a heterotopian approach. In his design, a huge strip of intense metropolitan desirability like a runway through the centre of London. 19 Within this giant strip, Koolhaas divided it into eleven different zones. Each space has a different and even contradictory function, but fuse without compromise.20

It is not my intention here to discuss the concern behind Koolhaas's design that individual desires are being swallowed up by reality in a frenzied and tolerant concerted effort of the collective unconscious. In terms of the design itself, Koolhaas also chooses to bring together different types of spaces in order to attract people to them. But on a practical level, the idea of a huge belt of buildings stretching across Southbridge and indeed the city of Edinburgh is clearly an impractical one. But given the particular topography of Edinburgh, could this urban belt be spread vertically to achieve the same effect as the heterotopia itself?

19 Rem Koolhaas, Bruce Mau, and Office For Metropolitan Architecture, S, M, L, XL (New York: Monacelli Press, 1998), 7.

20 Rem Koolhaas, Bruce Mau, and Office For Metropolitan Architecture, S, M, L, XL (New York: Monacelli Press, 1998), 9.

21 Rem Koolhaas, Bruce Mau, and Office For Metropolitan Architecture, Exodus, or the voluntary prisoners of architecture, 1972, in Rem Koolhaas, S, M, L, XL (New York: Monacelli Press, 1998), 4.

2.1 What's heterotopic chimney

It is important to acknowledge that South Bridge is clearly a geographically defined space, as opposed to a ship that connects different types of places through its own movement. But the same effect can be achieved by placing different types of space in the South Bridge and relying on a heterotopian space. The chimneys on the buildings on either side of the South Bridge have the potential to become a heterotopia. The reason for this is that, firstly, although there is space inside the chimney, this space is not normally used by people who would enter it, and it was not even designed to be easily accessible to adults (in the past the clean-up was usually done by smaller adults or children). The second point is that the chimney naturally connects the different spaces.

2.2 Why heterotopic chimney

Why try to give Southbridge the nature of a heterotopia, or what changes could be brought about by Southbridge becoming a heterotopia? David Grahame Shane in Recombinant Urbanism refers to the character of heterotopia embodied in the three "M's": the mirror-function, which reverses the surrounding codes; the multiple pockets within the heterotopia enclave, which facilitate mixture and change; and a utopic “simulation” that reflects in miniature the entire surrounding system, with its code altered or reversed.23 From Shane's description of Heterotopia, we can find that heterotopia allows us to observe the hidden codes of the city, i.e. we can observe the different relationships in the city through the altered South Bridge.

On the other hand, Shane mentions the interesting phenomenon of the expansion of the universities in Oxford and Cambridge and the system they have developed, which over time has had a significant impact on the development of the city as a whole. He summaries a pattern for this phenomenon: the agglomeration of specialized cells in specialized, heterotopic enclaves. By this process a city may be charged from below over time by forces working through crisis heterotopias.24

24 David Grahame Shane. 2013. Recombinant Urbanism: Conceptual Modeling in Architecture, Urban Design and City Theory. Chichester: Wiley. p.249.

This means that by placing Southbridge into the Heterotopic Chimney, Southbridge itself will evolve and influence Edinburgh in an iterative process, i.e. putting Edinburgh in a state of configured urbanism. This state of affairs does not make the Heterotopic Chimney or even Southbridge incompatible with Edinburgh, but rather they are harmoniously integrated into the city. As Stan Allen proposed that These fragments disappear into the composition not because their fragmentary nature has been concealed or cover over, but because they have themselves redefined the rules for “fitting in.”’. The whole and the parts submit to the same geometric rules.25

25 Stanley Allen and G. B. Piranesi, “Piranesi’s ‘Campo Marzio’: An Experimental Design,” Assemblage, no. 10 (December 1989), 97, https://doi.org/10.2307/3171144.

2.2 Why heterotopic chimney

Southbridge itself has the potential to become an archive in its own right, in a process of constant configuration. On the one hand, it is because Southbridge, as a participant and witness of different periods in Edinburgh, is already a place where memories are original and structurally decomposed, and it has the externality needed for an archive; 26 on the other hand, due to the nature of the material of Southbridge itself, it has visible traces of changes over time, and these traces themselves are already faithful statements of events and things.27 The archive itself has the property of being a heterotopia, an infinite accumulation of time, collecting and displaying content from different periods.28

26 Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever A Freudian Impression, trans. Eric Prenowitz (Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 1996). 11.

27 Carolyn Steedman and Rutgers University Press, Dust : The Archive and Cultural History (Machester, Uk: Manchester University Press, 2001). 2.

28 Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” Diacritics 16, no. 1 (1986): 22–27, https://doi. org/10.2307/464648.28.