Hypermobility in Movement

PLUS

• The Trainers’ Perspective: UniSport Nationals 2022 2022 SMA Conference: A Recap

VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022

health

Sport

REGULARS

4

From the Chair New Chair, Dr Kay Copeland, recaps key achievements from the year and announces next year’s ASICS SMA Conference.

5

From the CEO

Jamie Crain reviews the 2022 SMA Conference and looks ahead to what the organisation has planned for the 60th year of SMA.

FEATURES

6

Hypermobility as a Risk Factor for ACL Injuries in Sport

Queensland based physiotherapist, Dr Sue Keays, looks at how joint hypermobility is a risk factor for athletes, with a specific focus on the ACL.

13

2022 SMA Conference: A Recap

We review the annual Conference, held at RACV Royal Pines Resort, and celebrate the leaders in sports medicine, along with some of the brightest young researchers on show.

16

Stretching in our Hypermobile Athletes: Is it Ever a Good Idea?

Dr Myles Murphy explores the methods and ideas around stretching in hypermobile athletes, and if the current research shows this to be an overall positive or negative.

21

The Trainers Perspective: UniSport Nationals 2022

SMA-accredited sports trainers, Gabrielle Curan and Claire Kinman, share their experience providing coverage at the UniSports National in Perth this year.

Opinions expressed throughout the magazine are the contributors’ own and do not necessarily reflect the views or policy of Sports Medicine Australia (SMA). Members and readers are advised that SMA cannot be held responsible for the accuracy of statements made in advertisements nor the quality of goods or services advertised. All materials copyright. On acceptance of an article for publication, copyright passes to the publisher.

Publisher

Sports Medicine Australia Melbourne Sports Centre, 10 Brens Drive, Parkville VIC 3206 sma.org.au ISSN No. 2205-1244 PP No. 226480/00028

Marketing

and Member Engagement Manager

Sarah Hope

Copy Editors

Archie Veera and Jack Sullivan

Design/Typesetting Perry Watson Design

Cover photograph gettyimages/wavebreakmedia Content photographs

Author supplied; www.gettyimages.com.au

Contents

2�VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022

26

Hypermobility and Knee Surgery

Prof Brian Devitt and Dr Tom Doyle discuss the impact hypermobility has on the musculoskeletal system and how it forearms surgeons.

Volume 40 • Issue 2 • 2022

32

INTERVIEWS 30 5 Minutes with

38

34

VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022 3

People who Shaped SMA: Dr Andrea Mosler

Dr Jason Lam

Sports Trainer Highlight: Innalla Press

Sports Medicine Around the World: Greece

Iam excited to present the second edition of Volume 40 of Sport Health. It is a privilege to be appointed Chair of Sports Medicine Australia and to continue the work of my esteemed colleague Professor Gregory Kolt. His contribution to the organisation across his time as Chair has been outstanding and provides an extremely solid foundation for us to grow from. The implementation of the three-year strategic plan has guided SMA, and the appointment of a new management team, headed by CEO Jamie Crain will remain key pillars for the organisation. I look forward to welcoming our new and returning members for 2023, and continuing to work with our highly respected SMA Directors to grow SMA further.

It was a pleasure to catch up with friends and colleagues at the first SMA face-to-face Conference since 2019, which has recently concluded at the RACV Royal Pines Resort on the Gold Coast QLD. Welcoming some of the leading sports medicine and sports science clinicians and researchers from around the globe, attendees were treated to fascinating insight into a plethora of topics and a comprehensive scientific program.

On show was an array of brand-new research and presentations from some of the brightest researchers pioneering in their respective fields.

I would like to congratulate all the Award winners from this year’s Conference. The quality of work on display over the week was at an all-time high. I would also like to recognise the newly inducted Fellows for their contributions to SMA as myself and the rest of the Board welcome you.

Finally, I would like to thank Dr Ebonie Rio and Dr Luke Kelly, Conference Cochairs and the Conference Committee for their diligence and outstanding work in putting the Conference Program together. Also, thank you to Jamie Crain and all the staff who made this Conference possible as well as the RACV Royal Pines Resort for their hospitality and the picturesque setting provided for the week.

Looking forward to the new year, we have a large number of professional development events and training courses planned which we are excited to share with our members. We have also set a date and location for next year’s ASICS SMA Conference, which will be held at the Novotel Twin Waters Resort on Sunshine Coast from 11-14 October 2023. After the success of this year’s event, I look forward to welcoming everyone back up to Queensland next year.

I hope you enjoy what has been put together for Volume 40, Issue 2 of Sport Health and I look forward to 2023 with SMA!

This year’s conference gave us the opportunity to celebrate the best of Sports Medicine expertise and research, whilst generating the opportunity to network again with friends and colleagues face-to-face.

NEWLY APPOINTED SMA BOARD CHAIR, DR KAY COPELAND LOOKS BACK AT THE RECENT SMA CONFERENCE HELD ON THE GOLD COAST AND PREVIEWS WHAT IS TO COME IN 2023.

Dr Kay Copeland

FROM THE CHAIR

4�VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022 F ROM THE CHAIR

Celebrating our recent Conference and looking forward to the new year.

FROM THE CEO

The 2022 SMA Conference and welcoming the new Chair of the Board.

SMA CEO JAMIE CRAIN RECAPS KEY EVENTS

FROM THE YEAR AND LOOKS TOWARDS WHAT THE 60TH YEAR OF SMA WILL BRING

Welcome to the last Sport Health for 2022.

As many of you would know, we have just wrapped up the 2022 SMA Conference held on the Gold Coast. I’m sure many of our readership attended and I hope that all of you enjoyed being face-toface once again and were immersed in the range of expert panellists and topics on show at the cutting edge of sports medicine. It was a pleasure for me to be able to see and hear from many of our members.

We had many highlights this year including a wonderful Welcome Reception which set the tone for the entire week. As per SMA tradition, we opened the Conference with our Refshauge Lecture, this year delivered by Dr Susan White AM who spoke on how Sports Medicine is “like a box of chocolates”. We also held the SMA Annual General Meeting where we welcomed our broader members to have their say on the direction of the organisation and it was delightful to see many faces in attendance.

2023

60 years

recognised as a specialist sports and exercise physiotherapist by the Australian College of Physiotherapy, and I congratulate her on her new position. I would also like to thank Professor Gregory Kolt for his work as the Chair since I have been CEO and look forward to continuing to work with him as a member of the Board.

In line with our Strategic Plan, SMA has this year increased the number of in-person courses and professional development events, alongside our highly successful webinars. I would like to thank our State Councils, our Conference Committee, Scientific Advisory Committee, staff, presenters, and all our wonderful volunteers who helped make 2022 the success it was. Looking forward, we go into 2023 celebrating 60 years of SMA and will continue to grow the value for our members to an all-new level with many exciting new initiatives ahead of us.

Following the AGM, the new Board appointed Dr Kay Copeland as our new Chair. Kay has been with the organisation since 1985 and has been one of the key contributors to the success of SMA over the time she has been involved. This is alongside her clinical experience, with over 30 years of work in elite sports and being

This edition of Sport Health focuses on Hypermobility with authors from around the world contributing to share their research and opinions on this complex and multi-faceted topic. I thank all the contributors who put their time into collating the articles for this edition.

Jamie Crain jamie.crain@sma.org.au

marks

of SMA as an organisation.

This is a major achievement for those who have been involved over this period and I’m delighted to be celebrating this with our members next year.

FROM THE CEO VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022 5

Generalised hypermobility as a risk factor for anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury in sport

BY DR SUE KEAYS

Hypermobility of joints may be an asset for athletes in certain sports. It is considered to be an advantage for gymnasts, spin bowlers, acrobats, divers and ballet dancers. However, in many instances excessive range of motion during sport leads to injury. Several studies have shown that generalised hypermobility, as assessed on Beighton’s criteria, is related to increased injury rates in soccer, rugby and netball. In relation to the knee, hypermobility is well recognised as a risk factor for injury. We know from previous studies, that a high percentage of non-contact ACL injuries occur in athletes who have generalised hypermobility especially those athletes with increased knee hyperextension. It has been shown that as high as 60% of ACL injured

patients demonstrate generalised hypermobility whereas only 5-20% of the general population do. Alarmingly, knee hyperextension is found in nearly 80% of ACL-injured patients and Myer et al. have shown that having hyperextending knees increases the risk of ACL injury by five-fold in females.

What is unknown however is 1. How generalised hypermobility compares to other risk factors known to be associated with ACL injury and 2. Whether ACL injury is related to exposing children at a young age to excessive sport, leading to the stretching of ligaments and acquired hypermobility. Graham et al have highlighted the possibility that hypermobility may be acquired through training initiated in childhood when ligaments may be more vulnerable to

stretching. With the emerging higher rate of ACL injuries in children this possibility requires investigation. Based on twin studies, other researchers including Hakim et al believe that hypermobility is strongly genetically determined and is potentially associated with several genes. This may include the gene encoding COL1A1 which has been specifically linked to ACL ruptures and possibly relates to collagen laxity. Extreme forms of generalised hypermobility which include Ehlers-Danlos, Marfan and Hypermobility Syndrome are considered to have a genetic component.

Inadditiontogeneralised hypermobility,therearemanyother factorsthatpredisposetoACLinjury. These include intrinsic factors such as hormonal factors, female sex,

6�VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022 FE ATURE

static lower limb alignment, bony anatomy such as increased posterior tibial slope, poor neuromotor control and lower limb biomechanics as well as extrinsic factors like playing surfaces and incorrect footwear.

We chose to study those predisposing factors commonly observed in ACLinjured patients in our clinic, in order to better understand the role they play in ACL injury. These factors included generalised hypermobility, faulty lower limb posture, intercondylar notch size in addition to early exposure to cutting sports which is often reported in patients with ACL injuries. We chose to study siblings because of the unexpectedly high number of patients who reported having at least one sibling with a ruptured ACL.

to generalised hypermobility,

ACL

Table 1. Frequency counts/mean values of intrinsic and extrinsic factors in 48 siblings, 24 with and 24 without an ACL rupture. At-risk feature Measure Injured N=24 Uninjured N=24 p value Generalised Joint Laxity Beighton’s ≥ 4/9 14 (58%)4 (17%) 0.003 Lower Limb Alignment, measured in standing Knee hyperextension 22 (92%) 5 (20%) <0.001 Valgus 11(46%) 4(17%) 0.01 Pronation 13(54%) 3 (13%) 0.002 Notch size Notch index <0.2 16 (66%) 1 (4%) <0.001 Early Sports Participation Age of starting sport (mean) 7.5 7 0.229 Times per week (mean) 3.52 3.58 0.812 VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022 7 FEATURE

In addition

there are many other factors that predispose to

injury.

Generalised hypermobility

risk factor for anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury in sport

Thisstudyaimedtocomparethe predisposingfactorsbetweensiblings, withandwithoutACLinjuries,inorder to determine which factor was most predictive of ACL injury. That is, we investigated which factor/s were the most signiicant in discriminating between 24 siblings from 10 families with ACL injuries (injured group) from 24 siblings from 10 unrelated families without ACL injuries (uninjured group). Five intrinsic anatomical risk factors assessed were: generalised hypermobility; knee hyperextension; valgus knee alignment; pronation and size of the intercondylar notch Two extrinsic factors assessed were; age of commencement of cutting sport and the frequency of playing sport, including the sports played. While we have previously shown that generalised hypermobility, limb posture and narrow notches are common in siblings with ACL ruptures, their comparative ability to predict ACL injury is not known. In addition, the role played by early involvement in children’s sport in impacting on ACL injury has not been explored as far as is known. We hypothesised that 1. All intrinsic factors would occur more frequently in the injured sibling group compared to the uninjured group and 2. That compared to the uninjured group, those with ACL injuries would have commenced cutting sport at an earlier age and played more frequently.

METHODS

Participants

Twenty-one of the 24 injured siblings from 10 families were recruited from one physiotherapy clinic. Three siblings were invited to join the study. All injured siblings had an ACL rupture conirmed on MRI or a positive pivot shift test performed by an orthopaedic surgeon. Seventeen of the 24 patients had undergone reconstructive surgery with nine receiving patellar tendon grafts, seven receiving semitendinosus/gracilis graft, and one an extra-articular

reconstruction.The24uninjuredsiblings wererecruitedfromlocalsportsclubs, friendsandfamily.Theywere matched with the injured family groups for age, sex and family composition. There were four sets of three siblings and six sets of two siblings in each group. There were 15 males and 9 females in each group. The average age of the injured group was 27 (±5.4) years old and of the uninjured group was 30 (±5.4) years old. All 48 siblings were examined by a physiotherapist and had knee x-rays including an intercondylar view. Ethical clearance, including approval for radiographsofhealthykneeswas grantedforthisstudyandallpatients

Assessment

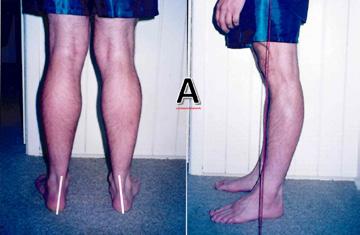

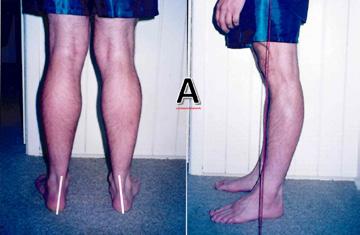

Generalised hypermobility was assessed using Beighton’s Criteria (Figure 1). Standing hyperextension and knee valgus were measured using a goniometer in weight-bearing (WB) and graded as 0 ,1 or 2. Pronation of the forefoot and hindfoot were assessed, the latter using Coplan’s line. (Figure 2). Notch width index was measured on the intercondylar x-ray view (Figure 2). Extrinsic environmental factors were assessed using a brief sports questionnaire. Further details of the methods have been described before.

signedinformedconsenttotakepart.

FEATURE 8�VOLUME 40 ISSU E 2 2022

as a

Statistical Analyses

Chi-square analyses were used to determine differences in frequency counts of the presence of generalised hypermobility, faulty lower limb posture (knee hyperextension, valgus and pronation) and narrow intercondylar notch width size between injured and uninjured siblings. T-tests were used to compare the age of commencement of sport and the number of times played per week between injured and uninjured siblings. To address our main question a discriminant analysis assessed which of the above seven factors was the most significant in predicting which patients were most likely to have a ruptured ACL.

RESULTS

Our results showed a significant difference between the injured and uninjured groups for all the intrinsic measures: 58% of injured and 17% of uninjured siblings demonstrated generalised hypermobility (p=.003); 92% of injured and 20% of uninjured siblings had knee hyperextension (p<.001); 46% of injured and 17% of uninjured siblings demonstrated knee valgus (p=.01); 54% of injured and 13% of uninjured siblings demonstrated pronation (p=.002). (Table 1) We found no significant difference between groups for involvement in early sport. The mean age of sports commencement for the injured siblings was 7.5 years and for the uninjured 7 years (p=.229); the mean number of times played per week was 3.52 for the injured and 3.58 for the uninjured (p=.812). Contrary to our hypothesis, the injured group did not commence sport at an earlier age or play more frequently. Interestingly, more siblings with ACL injuries (50%) played soccer in the U8 team than did uninjured siblings (33%). Other sports commonly played included cricket, netball, and Australian Rules football. Some children played 4-5 sports simultaneously. Some played sport 6 times weekly but the average was 3-5 times weekly.

Our discriminant analysis showed that three of our measures could discriminate between injured and uninjured groups with an 87.5% chance of correct classification. These were generalised hypermobility r=.613; knee hyperextension r=.637; and narrow notches r=.544 (Table). The age of commencement of sport and the frequency of sport played were similar between the injured and uninjured group indicating that playing sport on average three times weekly from age 7 did not contribute to ACL injury.

DISCUSSION

The most important finding of this study is that generalised hypermobility and knee hyperextension present the highest risk for ACL injury of those assessed. These two features are most easily detected in screening for those at risk of ACL injury. Although this study focussed on siblings with ACL injuries, this finding would be relevant to all sportspeople. Having narrow intercondylar notches was also an important risk factor but

Table 2: Equality of Means used for the Discriminant analysis

Possible discriminating at-risk factors (means)

ACL- injured group Uninjured l group P value

GJH: Total number of 9 hypermobile joints 4.5 2.8 .000

WB hyperextension: 0=nil; 1=5-9°:2=≥10° 1.458 0.375 .000

Standing valgus:0=,6°; 1=7-9°:2=≥10° 0.792 0.208 0.01

Standing pronation: 0=nil; 1=either forefoot or hindfoot; 2= forefoot and hindfoot

0.792 0.166 .003

NWI: ratio of notch size to distal femoral width 0.189 0.239 .000

Table 3. Discriminant analysis: Structure Matrix showing the r value for each possible discriminator. r values over .4 are usually considered to represent significant discriminators.

Measure r value

WB knee hyperextension .637

Beighton’s score .613

Notch Width Index -.544

Pronation .387

Valgus .327

Age of starting sport .128 Times per week -.029

There is no doubt that ACL rupture results from the complex interaction of multiple factors.

FEATURE VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022 9

Generalised hypermobility as a risk factor for anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury in sport

requires an x-ray to identify. Knee valgus and pronation, although significantly different in frequency between our groups, did not prove to be discriminators for ACL injury. Interestingly, these postures have been related to hypermobility previously.

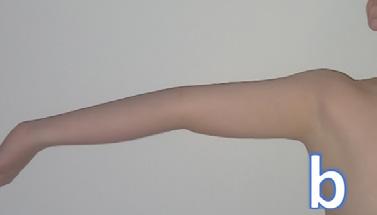

We found no evidence that commencing sport at an age when ligaments are considered to be vulnerable to stretching is a factor in later ACL injury. Early commencement of sport did not discriminate the injured from uninjured groups. We hypothesised that injured siblings would have been involved in cutting sports frequently at an earlier age compared to uninjured siblings but this was not so. Australian children seem to play sport frequently from a young age without putting their knees at risk. This may not apply if other risk factors are present in sporting children, particularly generalised hypermobility and knee hyperextension. (Figure 3) Importantly,

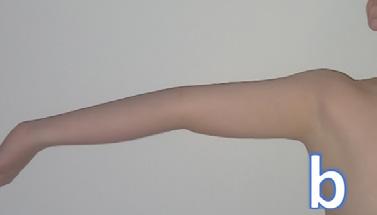

knee hyperextension can occur without generalised hypermobility. Ramesh et al reported that while 42.6% of ACL injured patients have generalised hypermobility, 78.7% demonstrate knee hyperextension. This finding does suggest that knee hyperextension can be acquired in the absence of generalised hypermobility. Knee hyperextension without generalised hypermobility is often observed in ACL-injured patients in the clinic but our study was unable to show that early participation in cutting sport was related to this. Hyperextending knees have also been shown to demonstrate increased anterior laxity and reduced proprioception which further enhances the risk of injury. As mentioned, Myer et al [11] showed that knee hyperextension in females, increased the likelihood of ACL injury five-fold (Figure 4). The mechanism by which a hyperextending knee contributes to injury has been reported: As the knee hyperextends the ACL is stretched and impinges

on the anterior margin of the roof of the intercondylar notch. This is shown to occur at 6.3° of hyperextension.

This study has shown that generalized hypermobility and knee hyperextension are two significant predictors of ACL injury in sport. Both remain very simple and powerful ways of screening those vulnerable to ACL injury. It is strongly recommended by current clinical practice guidelines that those at risk of ACL injury should attend prevention programs as should all 12–25-yearolds involved in high level sport.

Over 2 million people rupture their ACL every year and the incidence is increasing especially in adolescents. Many of these injuries can be prevented. All of us in contact with young people playing sport have a role to play in early identification of those at risk and in directing those who are most

Figure 1

Assessment of generalised hypermobility using Beighton’s Criteria in a patient with an ACL rupture, (a) Hyperextension of the fifth metacarpophalangeal joint to >90degrees. (b) Thumb opposition and wrist flexion to reach the forearm

(c) Trunk flexion to reach palms to Floor or beyond in this case. (d) Elbow hyperextension ≥10 degrees (e) Non-weight bearing knee hyperextension>10.

One point is allocated for each of nine joints measured, If 4/9 joints meet the above criteria, the individual is considered positive for generalized hypermobility.

Figure 2

(a) Lower limb posture assessed forefoot and hindfoot pronation, knee valgus and hyperextension. These measures were graded as 0, 1 or 2. For pronation 1 indicated either forefoot or hindfoot pronation, 2=both were present. For valgus 0=≤6° 1=,7-9°, 2≥10°. For hyperextension 1=5-9°, 2≥10° (b) Shows a broad notch in a sibling with no ACL injury and a narrow notch in an unrelated sibling with a narrow notch. Femoral intercondylar notch width was assessed as the ratio of the notch to the width of the femoral condyles at the level of the popliteal groove The above features are all associated with ACL injury but knee hyperextension, together with generalised hypermobility was the strongest predictor of ACL injury, found in this study.

FEATURE 10 �VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022

vulnerable to prevention programs. It is important to know that neuromuscular dynamic stability training programs have been shown to reduce ACL injuries by as much as 50-70%. Such training programs incorporate the ABC evidence-based strategies for ACL prevention. They include Prep to Play from La Trobe University, the PEP program developed in California and the FIFA 11+ program.

Conclusion

This study has shown that hypermobility is highly significantly associated with ACL injury, especially knee hyperextension which of the factors we investigated, was the strongest predictor of ACL rupture. We did not find a relationship between early participation in cutting sports and future ACL injury but young sports people with joint hypermobility may be at greater risk of injury. Hypermobility is a simple tool for detecting those at risk of ACL injury and prevention programs reduce ACL injury by more than 50%.

Figure 4

Knee hyperextension was found to be the most significant predictor of ACL injury.

Author Bio

Dr Sue Keays isaSouthAfrican-trained physiotherapist workinginprivate practiceontheSunshineCoastinthefield oforthopaedicsandsportsmedicine.She hasanHonoursinPsychologyandaPhD inACLrehabilitationfromtheUniversityof Queensland.Shehasservedonregional

Figure 3. a. Early commencement of sport by itself was not shown to increase the risk of future ACL injury but b-f. Children with hypermobility may be at greater risk of injury in the future

For article references, please email info@sma.org.au.

committeesoftheAPAandSMAovertime.Suehas publishedquiteextensivelyandpresentedatnumerous conferences Shehasanongoingenthusiasmforclinical researchandiscurrentlyinvolvedinaprospective25-year ACLfollow-upstudy.SueisAdjunctAssociateProfessorat theUniversityoftheSunshineCoastandisontheEditorial BoardoftheAmericanJournalofSportsMedicine.

FEATURE VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022 11

2022 SMA Conference

a recap

After a three-year hiatus of an in-person event, the SMA Annual Conference returned to its face-toface format in 2022. On 16 November, the picturesque RACV Royal Pines Resort on the Gold Coast saw Sports Medicine professionals arrive to experience the very best that the industry has to offer. The next four days was a deep dive into insights from leaders in their fields internationally, imparting their knowledge and expertise. We welcomed early career researchers presenting on the cutting edge of research, unveiling findings and prompting debate and discussions with the brightest minds in their respective vocations. Friends and colleagues came together from around Australia—and the world—to network and catch up at the leading Sports Medicine Conference in the Southern Hemisphere.

The highlight of the first day was welcoming this year’s Refshauge Lecturer, Dr Susan White AM. It was a privilege to have such an esteemed member of our industry presenting the opening lecture for 2022’s iteration.

VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022 13 F EATURE

2022 SMA Conference a recap

She is currently the Director of Performance Health Services and Chief Medical Officer at the Victorian Institute of Sport as well as having an extensive background with SMA heading up the Women in Sport Committee for many years. Her presentation, “Sports Medicine is like a Box of Chocolates” captured the audience and set the tone for the rest of the Conference. The Trade Exhibition opened on Wednesday, with exhibitors showcasing cutting-edge technology and treatment options.

Thursday saw the first full day of presentations. Keynote speaker, Professor John Hawley, presented on ChronoNutrition and when to fuel for exercise, along with a range of Invited speaker and paper presentations delivered on Upper Limb, Hip and Groin, Physical Activity Interventions and Health, and Female Athletes. Across Friday and Saturday, Professor Karyn Esser presented on Circadian Clocks, Dr Phathokuhle Zondi on Inclusive Research, Dr Esther van Sluijs on Promoting Physical Activity in Young People, Professor Jill Cook on Tendinopathy Research Gaps, and Professor Vincent Gouttebarge spoke on Mental Health Symptoms in Elite Sports. SMA was delighted to host this rigorous display of expert knowledge in the multidisciplinary field of Sports Medicine.

To compliment the Conference program, Friday featured the Scientific Poster presentations, and the best posters were recognised and awarded on Friday evening. Saturday saw the Best of the Best and the Gala Dinner where we celebrated the winners from the previous days of presentations. We commended the finest of senior and junior career researchers with the seven career research awards presented across a range of disciplines and topics. Dr Reidar Lystad, won the esteemed ASICS Medal for Best Paper Overall. Associate Professor Bruce Mitchell received the prestigious Chair’s Award for his decades worth of outstanding service, dedication and loyal contributions to SMA and its Mission.

We held the SMA Annual General Meeting, and the ASMF Fellows Dinner on Thursday night. During the dinner, new Fellows were inducted into this prestigious group and the pioneers of the field were celebrated and recognised.

SMA thanks everyone who attended and made the event what it was—an environment of collegiality, warmth and knowledge sharing. Thanks also goes to ASICS for their ongoing support as SMA’s major sponsor, our partner Strapit, session and speaker sponsors, SEPA and Bared Footwear and all our Trade Exhibitors. We

14 �VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022 FEAT URE

appreciate the extended support from our partners and collaborators, JSAMS, BJSM and Destination Gold Coast.

In 2023, we are excited to announce that we will be going to the Sunshine Coast. The ASICS SMA Conference will travel to Novotel Twin Waters Resort from 11-14 October 2023 and we look forward to welcoming back everyone who made the 2022 Conference so special.

VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022 15 F EATURE

DR MYLES MURPHY

Stretching In Our Hypermobile Athletes: Is It Ever A Good Idea?

FEATURE 16 �VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022

What is the point of stretching?

Should we or should we not be stretching remains one of the topics within Sports Medicine and Sports Science that has staunch believers on both sides of the fence and is often recommended by clinicians to improve performance or reduce injury rates. Whilst some evidence has shown the capacity for regular stretching to improve muscle length and joint range of motion it should not be recommended as a mainstay for injury prevention. Stretching is also performed as a therapeutic exercise to relieve symptoms of muscle of joint ‘tightness’ or ‘stiffness’ experience by patients.

Prescribing individualised rehabilitation, not rehabilitation recipes.

As a clinician it is important that whilst we are informed by the evidence, we assess the individual in front of us and determine what it is the individual might need so that we are providing targeted management and not rehabilitation recipes. For example, if we use the knee extension test as an example of hamstring length, stretching can significantly improve range of motion. However, before prescribing every patient with hamstring stretching it is important that clinicians first assess the athlete

to determine whether the person even requires additional hamstring flexibility. Many athletes will already have sufficient hamstring length for their required sport. Clinicians must also remember that the requirements for hamstring length will be different between sports (e.g., a gymnast would require significantly greater hamstring flexibility than a swimmer). By only providing stretching to athletes with muscle length that limits their sporting performance we also reduce the time burden on other athletes who already have sufficient range and would likely be stretching for little to no added benefit.

Appreciate the difference between feeling tight, and actually having reduced muscle length.

One of the common clinical beliefs is that when someone is feeling tight, this means they have reduced muscle length. However, it is possible for someone to have the sensation of ‘tightness’ or ‘stiffness’ or ‘tension’ and not actually have reduced muscle length. It has been theorised that the feeling of muscle tightness, or restriction can also be due to chronic overloading of a normal muscle, or normal loading through a weakened muscle. Therefore, the solution to these problems is unlikely to be stretching. Instead better load management and providing increased strength to the weak muscle group would, in theory, provide better outcomes. I have

VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022 17 FEATURE

Before prescribing every patient with hamstring stretching, it is important that clinicians first assess the athlete to determine whether the person even requires additional hamstring flexibility.

Stretching In Our Hypermobile Athletes: Is It Ever A Good Idea?

presented the clinical decision-making tool I use when deciding to prescribe stretching with Figure 1. Due to the effect of stretching of our neural network, an athletes muscle tension may feel better immediately after stretching. However, this does not address the core problem of over-training or being under prepared for athletic loading due to muscle weakness.

Hypermobile athletes

Hypermobile athletes are one specific population where caution really must be taken before the prescription of a stretching program. Hypermobility is not a clear-cut risk factor for injury in sport and we demonstrated no relationship between hypermobility and shoulder injury in elite female cricket players. In clinical practice, I would typically see

18 �VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022 FEATURE

Figure 1. Deciding whether to stretch or strength when someone presents with muscle ‘tightness’

hypermobile patients not suffering from true muscle length impairments, and instead having a sensation of tightness and stiffness due to significant weakness within the muscle. We do not want to ignore that sensation of tightness however and if a patient is motivated and has time, recommending interventions such as foam rolling may be a way to reduce the sensation of tension, whilst not relying on external passive treatments (like massage), and not aggravate joint structures. However, some muscle groups may be truly tight in hypermobile patients and a thorough clinical assessment is needed to determine the patients management plan.

Author Bio

Dr Myles Murphy is an Australian Physiotherapy Association titled Sport and Exercise Physiotherapist.

Dr. Murphy has worked clinically as a physiotherapist for variety of elite sporting teams, including the Western Australian Cricket Association. While also working clinically, Dr. Murphy completed his PhD part-time at The University of Notre Dame Australia investigating the different mechanisms related to pain and dysfunction in people with lower-limb tendinopathy.

FEATURE VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022 1 9

Hypermobility is not a clear-cut risk factor for injury in sport and we demonstrated no relationship between hypermobility and shoulder injury in elite female cricket players.

Online learning. Human support. Learn more and apply online.acu.edu.au CRICOS Reg: 00004G Gain advanced skills and recognition in sports and exercise physiotherapy with a Master of Sports and Exercise Physiotherapy, or combine it with our industry-relevant Master of High Performance Sport. You can also study postgraduate high performance sport, performance analysis or sports analytics. Kick goals in 2023 with ACU Online – high-quality, evidence-informed courses designed for online delivery.

Perspective

The Trainers

FEATURE VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022 21

UniSport Nationals 2022

The Trainers Perspective

In 2022, the UniSport Nationals celebrated over 100 years of showcasing the best that university sport and athletics has to offer, hosted in the scenic city of Perth, Western Australia. The event saw over 5,000 athletes travel from around the country to compete in 26 different sports with The University of Sydney taking out the title of National Champions after five days of competition. Once again, SMA was proud to supply a number of Sports Trainers to support these athletes and we were thrilled to give our members the opportunity to participate and showcase their skills as sports medicine professionals.

Gabrielle Curan is a Sports Trainer based out of Western Australia who jumped at the opportunity to get involved in this iteration of UniSport Nationals. Initially getting involved in the industry through taking on a role with a local football team and taking SMA Level 1 and 2 courses through her university course, she has been sub-contracting as a trainer

for a year and a half. ‘I ended up kind of like falling in love with the work’ says Gabby, ‘I was just talking to the presenter there about what they do with sports medicine and that kind of inspired me to get even more involved in the field of being a sports trainer.’

For Gabby, a typical day at the event would start by arriving at the grounds early, getting herself familiar with

the venue and coordinating with her contact for the day. Being based with Hockey for the majority of the event, she would situate herself between the fields so she could monitor multiple games and athletes. “I was mainly responding to injuries as they happened, I found that injury started to trickle in a bit more towards the end of the week,’ she also reiterated the importance of working with the individual teams and gaining a working relationship with the athletes.

With athletes travelling from nearly every major city, SMA also utilised their network of trainers across the country to travel out to Perth for the event. Claire Kinman, a sports trainer for the last two years, travelled from Queensland to be a part of the UniSports Nationals. With a background in Soccer and Rugby, she relished the challenge of taking part in an event which would challenge her as a trainer. ‘It was such a good experience’ says Claire, ‘getting out there, meeting different people from different parts of Australia,

UniSport Nationals staff were quite exceptional. They were incredibly supportive and were always there whenever I needed anything.

– Gabrielle Curan

UniSport Nationals 2022 FEATURE 22 �VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022

which can offer different learning experiences, how they might structure something could be slightly different, how they can diagnose or interpret something completely different.’

Working with the Netball teams, her day-to-day experiences changed depending on what teams and staff would be in attendance, along with what injuries she would be dealing with. ‘Every day was completely different. We’d set up somewhere different. We’d obviously have different people seeing us, different injuries, but generally throughout the day we would do the same thing. So, strap and look at injuries, manage on court, yet it was always a bit interesting. We’d turn up early, get ourselves sorted, see what the day would bring, and then go home, have fun adventuring throughout Perth,’ said Claire.

With such a unique sporting event, both Gabby and Claire touched on some of the injuries they helped manage and some of the challenges encountered. ‘I think the high volume

FEATURE VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022 23

The Trainers Perspective

of athletes,’ said Gabby, ‘one of the guys I remember, I would leave my little station to help someone out and before I even got back to my station, someone else would come and ask me for help!’ This was seconded by Claire, who added the element of working with different disciplines. ‘Some people had injuries that needed treatment, so to let them know that that’s not actually something we can do as sports trainers, and obviously, to refer them on to physios that we knew in the area or that we were advised of, that was sometimes challenging.’

Both trainers, however, highly recommended participating in the event and lauded the learnings they got from it. ‘The Unisport Nationals staff were quite exceptional,’ said Gabby, who went on to say that she was excited to hopefully be involved in the 2023 edition of the event. With the UniSports once again ramping up in the new year, the opportunities for Sports Trainers to be involved are plentiful.

In response to what she’d recommend to other trainers, Claire declared, ‘I’d say definitely do it. It’s an amazing opportunity. Honestly, once in a lifetime.’

I’m so grateful that I’ve done it. And honestly, I learnt so much – I met so many new people and have a whole different perspective of what sports training can be.

– Claire Kinman

UniSport Nationals 2022 FEATURE 24 �VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022

Hypermobility and Knee Surgery:

Beware what lurks in the woods!

PROFESSOR BRIAN DEVITT AND DR THOMAS R. DOYLE

“CHICKEN LICKEN, HENNY PENNY, COCKY LOCKEY, DUCKY LUCKY AND TURKEY LURKEY MET GOOSIE LOOSIE AND ASKED WHERE SHE WAS GOING. “I AM GOING TO THE WOOD,” SHE SAID. TURKEY LURKEY BEGGED HER TO STAY AND SHE DID.”

– Chicken Licken, by Vera Southgate

This is an excerpt from a well-known children’s book called ‘Chicken Licken’. Besides the obvious message this story imparts about the folly of following others into an action without thinking about it, it also provides an introduction to the character Goosie Loosie. As medical students studying paediatrics in Ireland, we were introduced to this term in a different setting, as a way to affectionately describe children with hypermobility. It became apparent that prospect of the sky falling down or the cunning Foxy Loxie waiting in the woods were only some of the dangers that Goosie Loosie

26 �VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022

could potentially face in life. Indeed, she was at high risk of shoulder dislocation, microinstability of the hip, patellar subluxation, and ACL rupture to mention just a few!

The impact hypermobility has on the musculoskeletal system is vast and wide ranging. For the purpose of this article, we will focus specifically on two common knee conditions: anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury and lateral patellar dislocation. We discuss that this condition is possibly more common than we realise and that being forewarned as to its presence will forearm us as surgeons to hopefully improve our management.

Epidemiology:

Joint hypermobility results from ligamentous laxity. It may occur in individuals with the primary genetic disorders, which affects the connective tissue matrix proteins; examples of this are Marfan syndrome and osteogenesis imperfecta. In addition, it may occur as part of other syndromes including trisomy 21 and bony dysplasia. In practice, the majority of cases of hypermobility exist as an isolated finding, which is hereafter referred to as ‘generalised joint laxity’ (GJL). It is often associated with other musculoskeletal symptoms such as pain and ‘clicking joints’, which are termed hypermobility syndrome.

GJL is commonly diagnosed by a clinical examination score, originally described by Beighton and Horan in 1969; it is a 9-point ordinal scale, which assesses the performance of 5 manoeuvres involving both the upper and lower limbs (Figure 1). It was originally introduced

for epidemiological studies involving the recognition of GJL in populations. As such, the scale is easy and quick to perform and has demonstrated good reproducibility. However, in the original description of the Beighton and Horan Score (BHS) there is lack of specific detail, which leaves them open for interpretation and uncertainty of application. In addition, variations have been found in BHS based on age, sex, and race; therefore, it has been proposed that thresholds should be individualized to subpopulations.

The epidemiology of GJL and the associated clinical sequelae has been significantly enhanced by a study by Clinch et al. published in 2011. Using the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children, this study performed a cross-sectional analysis of a cohort of 6,022 children. The study reported that the prevalence of GJL (as defined by a BHS of ≥4) in girls and boys aged 13.8 years was 27.5% and 10.6%, respectively. Girls were

more likely to be hypermobile at the fingers, thumbs, and trunk, whereas boys were most often hypermobile at the fingers, thumbs, and knees.

Pacey et al undertook a systematic review and meta-analysis of lower limb sporting injuries to assess the role of GJL. The authors reported a statistically non-significant but clinically relevant higher rate of lower limb injuries in the GJL group compared to the non-GJL individuals with an increased odds of injury of 43%. They found a significantly higher rate of knee injuries, with a 369% higher odds of knee injuries in contact sports in patients with GJL. Stewart et al, in a prospective study of a cohort of adult male rugby players, reported the prevalence of GJL (BHS

FEATURE VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022 27

In practice, the majority of cases of hypermobility exist as an isolated finding, which is hereafter referred to as ‘generalised joint laxity’ (GJL).

≥4) was 24% (12/51). The authors reported a significantly incidence of injury in players with GJL, mainly affecting knees. Notwithstanding the increased risk of injury, the presence of GJL also represents a surgical challenge when treating injuries.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: There is an increasing awareness of inherent physiological characteristics of patients as risk factors for recurrent instability following ACL reconstruction (ACLR). GJL is regarded as one such risk factor and has been implicated in not only ACL injury but also less favourable outcomes following ACLR. It has been proposed that this relates to the inherent connective tissue extensibility of the autograft and laxity of the secondary knee restraints, including the anterolateral complex (ALC).

GJL, as defined by the BHS, has been found to be a predictor of high-grade pivot shift following ACL injury. In two separate systematic reviews, both Sundemo et al and Krebs et al are in agreement that GJL represents a risk factor for ACL rupture and for poorer outcomes following ACLR. At medium

term follow up, not only are objective measures of knee laxity inferior in patient with GJL but so too are the patient reported outcomes and most importantly there is a significant increase in graft failure rates.

In an attempt to mitigate this, a number of authors have proposed augmenting an ACLR in this group with a lateral extra-articular tenodesis (LET) procedure with promising results. Helito et al have demonstrated a decreased rate of graft

failure and residual pivot shift following ACLR (hamstring autograft) with the addition of an anterolateral ligament (ALL) reconstruction compared to isolated ACLR. In the award winning Stability Study by Getgood et al, the addition of LET to a single-bundle hamstring tendon autograft ACLR in young patients at high risk of failure resulted in a statistically significant, clinically relevant reduction in graft rupture and persistent rotatory laxity at 2 years after surgery.

In the context of GJL and ACL injury, and considering the inherent limitations of the BHS, Kim et al have determined that knee hyperextension predicts postoperative knee laxity following ACLR regardless of the severity of GJL. Interestingly, the same group also showed that in the setting of ACLR in patients with knee hyperextension, autologous bonepatellar-tendon-bone graft produced less post-operative joint laxity compared to autologous hamstring grafts. It remains to be determined what the optimal choice of graft in ACLR is or whether the addition of a LET is necessary in all patient with GJL.

Lateral patellofemoral dislocation: GJL is classically cited as a key risk factor for recurrent patellofemoral instability following lateral patellofemoral dislocation. The concept of a patient being ‘born loose’ or ‘torn loose’ is often used as a means to differentiate between those who had predisposing factors increasing the risk of patellar dislocation compared to those who had a definitive traumatic event. Although this is possibly over simplistic it does highlight the importance of an awareness of specific factors that might place an individual at a greater risk of lateral patellar dislocation. Interestingly, a systematic review by Huntington et al which analysed the specific risk factors that predispose patients to recurrent dislocation following primary patellar dislocation did not list GJL; the

Hypermobility and Knee Surgery: Beware what lurks in the woods!

FEATURE 28 �VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022

Figure 1: Calculation of Beighton score.

There is an increasing awareness of inherent physiological characteristics of patients as risk factors for recurrent instability following ACL reconstruction (ACLR).

reported risk factors included younger age, open physes, trochlear dysplasia, elevated tibial tubercle-tibial groove distance, and patella alta. Nevertheless, it is likely that GJL co-exists in many of these patients and once again it may possibly affect the outcome of surgical management of this condition.

Medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction (MPFLR) has become one of the mainstays of surgical management of recurrent lateral patellar dislocation. Hiemstra et al, in one of the largest published cohorts of isolated MPFLR, analysed the prevalence of GJL and reported

a rate of 55%, which was well in excess of the expected population rate. Encouragingly, contrary to the results following ACLR, at 2-years follow up there was no difference in surgical failure, disease specific quality of life, symptom burden or functional testing between those patients with and without GJL.

In conclusion, as surgeons, we typically exist in a state of constant paranoia, mostly healthy, sometimes not. The little voice in our head and the scars of previous misjudgements remind us to take a complete history, be thorough in our clinical examination,

and meticulously assess preoperative imaging, so we have prior knowledge of possible dangers or problems, which may offer us a tactical advantage during surgery. Indeed, it is these very fears that make us conscientious. Although we may need to think and act on-the-fly during an operation, the best surgeons do their decision-making and planning long before they wash their hands. Therefore, an appreciation of the elasticity and yield point of the tissues we are working with is vitally important. So, perhaps if Goosie Loosie possessed just a little more paranoia, she, like her friends, may not have ended up on Foxy Loxie’s dinner plate!

For article references, please email info@sma.org.au.

Author Bio

Professor Brian Devitt is an internationally trained orthopaedic surgeon with subspecialty expertise in knee surgery. He has a particular interest in sporting injuries including anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction, meniscal repair, cartilage restoration procedures, multi-ligamentous knee reconstruction and hamstring repair.

Brian completed his medical school training at University College Dublin, Ireland, and carried out his specialist training in Trauma & Orthopaedics at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. He also achieved a Masters in Sports and Exercise Medicine. Brian chose to pursue a career in academic orthopaedic sports surgery, and carried out three years of fellowship training. The first year was a research fellowship at the Steadman Philippon Research Institute. He then carried out a clinical

Author Bio

Dr Tom Doyle, MB. BAO. BCh. & MCh candidate is an orthopaedic trainee in National Orthopaedic Hospital Cappagh in Ireland and is currently undertaking a masters degree in surgery. His main research interests

fellowship at the University of Toronto in sports surgery. Finally, he completed two clinical fellowships in Melbourne; the first was a knee reconstruction fellowship at OrthoSport Victoria (OSV) and the second a fellowship at Hip Arthroscopy Australia. Following his fellowship, Brian worked as a consultant orthopaedic surgeon at OSV and Epworth Healthcare.

Brian has a keen interest in research and is Full Professor and Chair of Orthopaedics and Surgical Biomechanics at Dublin City University. He has previously held the position of Director of Research & Education at OrthoSport Victoria in Melbourne. Brian has extensive research experience with a specific focus on clinical outcomes studies and biomechanical studies. His areas of interest are: ACL reconstruction, lateral extra-articular reconstruction, multi-ligament knee reconstruction, and hamstring repair. He has published extensively in all of these areas and speaks frequently at national and international meetings.

lie in sports surgery with particular attention to intra and extra articular knee and shoulder injuries. Tom’s passion for this work stems from playing rugby to a high level and a desire to improve patient outcomes by advancing knowledge in the field.

FEATURE VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022 29

Dr Jason Lam 5 minutes with

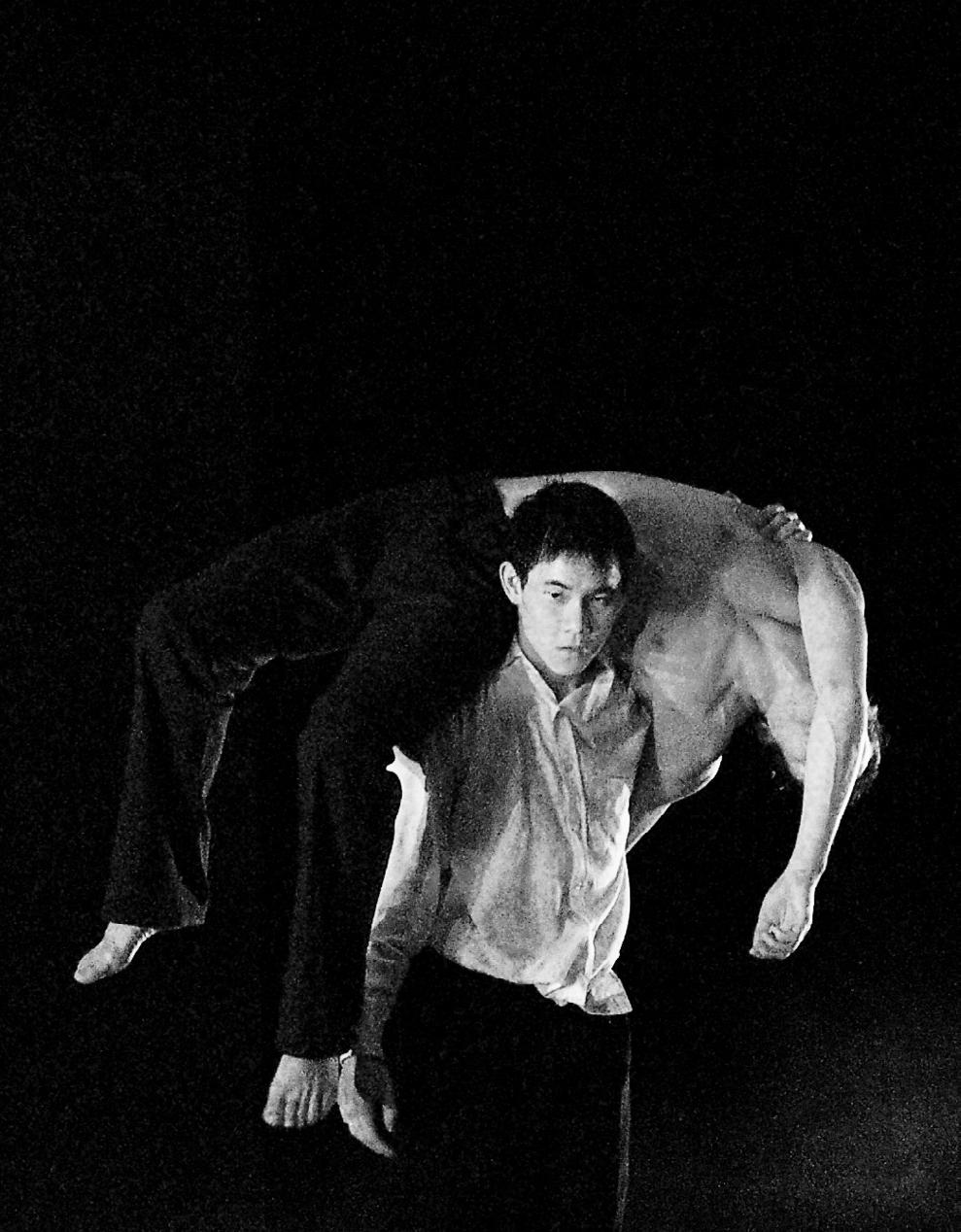

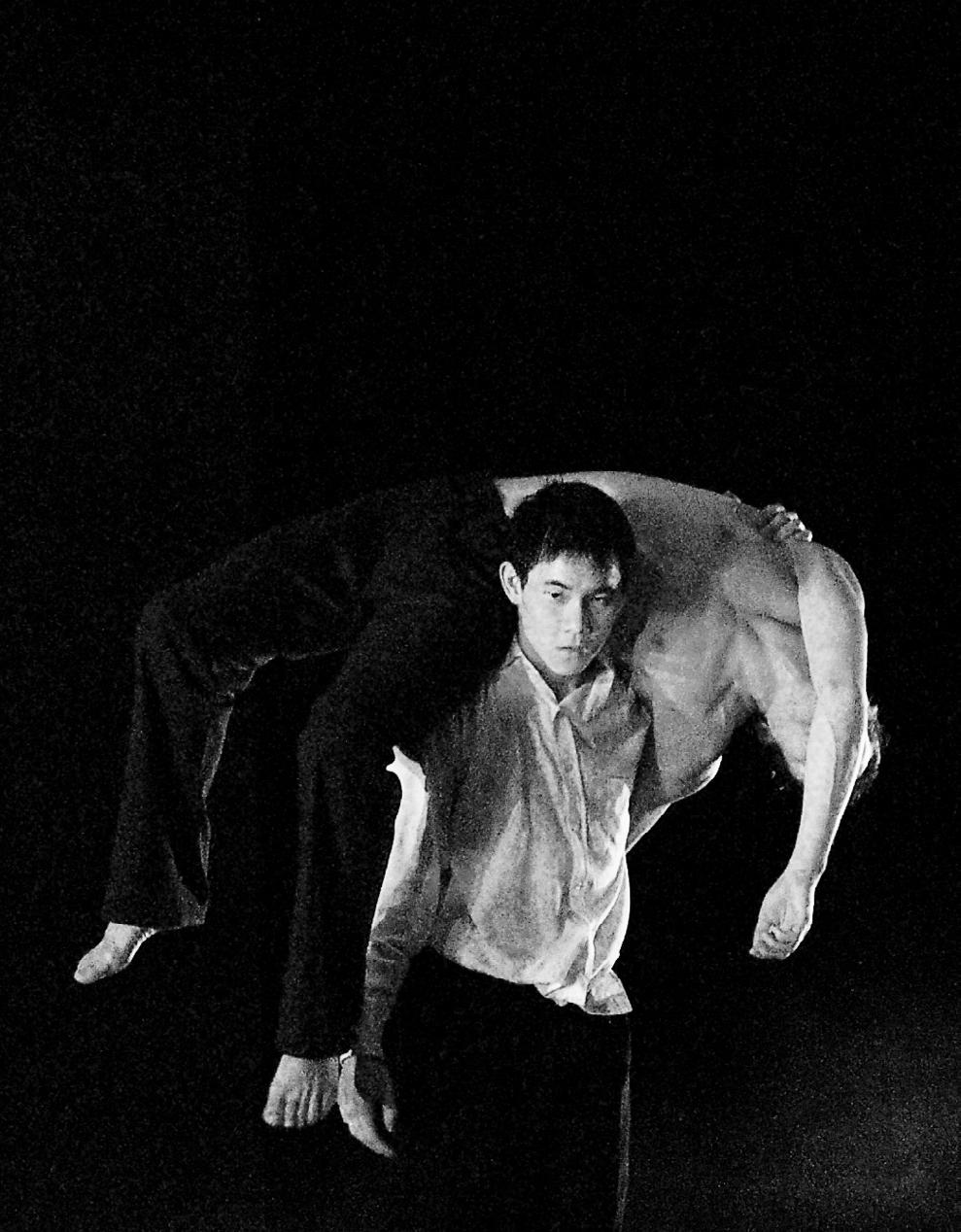

How did you transition from professional dancing into medicine?

I was a professional dancer with the Sydney Dance Company and did a lot of independent contemporary dance and dance theatre. It was all going well until I had a spontaneous pneumothorax and with dance in Australia being quite a small community, it was difficult to get hired. I always had an interest in medicine. When I was in high school and had to write down potential career avenues, I put down becoming a doctor.

I had also watched a lot of Scrubs and shows like that, which was a combination of my love of film and of medicine. So, when I was offered a masters in either medicine or film, I took the former.

5 MINUTES WITH 30 �VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022

Can you tell me about your experience as part of the Australian Ballet Medical team?

I was very fortunate to be given the opportunity to work with the Australian Ballet Medical Team. For five years I worked there and was able to be mentored by experienced practitioners and professors such as Dr Susan Mayes, Dr Andrew Garnham,DrEbonieRio, Prof Jill Cook,SophieEmery,Peta StellarandMichelleBergeron. It was also nice to be back in the world of dance and performance as it’s very exciting, so my people and I had really missed being in that environment.

Are there any unique challenges with working in dance medicine compared to standard practice?

As with many sports, you get the usual types of muscular injuries but there are some stereotypical injuries in dance that you don’t tend to see in other sports. This is just because dancers do strange things with their body that most other athletes don’t do, so it puts different demands on the body. One of the challenges that comes with working at the Australian Ballet is that they are insanely busy. There isn’t an off-season in dance, so there are challenges to the management of this from a health perspective Even the students have high workload so that is something that we must manage. There are a lot of new challenges to perform in this new generation with social media. There are numerous amounts of dubious advice around strength and health management so that is all quite challenging

What inspired you to go into education with medicine?

I always find joy in teaching. I was teaching when I was a dancer and then throughout medicine, we have students and registrars and I’ve always enjoyed that. I also worked as a Medical Educator for one of the GP training organisations. Teaching forces you to keep things fresh and to refine your understanding and then your explanation of things, which

has always been of great interest to me. The more I work in medicine, the larger the role of education has. It’s about working with the patient and educating them so that they can make an informed choice. This helps them understand why something needs to happen so they can be part of the process rather than being part of someone else’s decision making. This has helped me with how I explain stuff, rather than falling back on technical jargon, which is comforting for us but not very useful for the patient.

www.thedancedr.com.au

Do you have any advice for anyone starting out in medicine?

It’s all new, it’s exciting. It’s fun and it’s a fantastic field of study where you meet some great people. Just try to get into it early on. There are other ways within medicine. You don’t have to be a clinician.There’s research, there’s administration, there’s entrepreneurship, there’s e-health, there’s so many things within medicine. But also, if you hate it, there’s other things you can do with it. So don’t feel stuck.

5 MINUTES WITH VOLU ME 40 ISS UE 2 202 2 31

There isn’t an off-season in dance, so there are challenges to the management of this from a health perspective.

People Who Shaped SMA Dr Andrea Mosler

What inspired you to get into Sports Medicine?

I love this question. I grew up in a family that was crazy about sports and it was the thing that gelled our whole family together. I’ve always had a very strong caring instinct, I always wanted to do something that involved helping people and looking after people and that kind of motherly instinct was always in me from a very young age. When my mother hurt her neck, she went to a sports physio and I just thought it was an amazing job to do and then when I found out you could mix sport and physiotherapy, for me, that’s the perfect combination. So, I can work in sport and also care and look after people and it’s a challenging job. That’s really what inspired me to get into sports – love of sport and love of caring for people.

I did my PHD over in Doha, looking

at risk factors for hip and groin pain in elite male professional football players. This is something that stems way back from when I did my Sports Masters in the early nineties, and then through my clinical work, particularly with water polo and also with some of the junior football players that we had at the Institute of Sports. So, I had that clinical interest which naturally went into the research. When I came back from Qatar, I got a four-year clinical research fellowship funded by the NHMRC and that’s the position I’m working in now at La Trobe. That’s my main fellowship position but I’ve been working across a lot of different projects and one of the other areas that we’re doing a lot of work in is injury prevention in the female athletes and working within an INSPORT project.

PEOPLE WHO SHAPED SMA 32 �VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022

Can you tell us a bit about your research and your educational background?

Mosler

Are there any notable or memorable experiences from your career that you would like to share with us?

I’ve just been so blessed with my career, I have so many highlights. One of them was when I went back to do my sports masters at the University of South Australia. I think that gave me a lifelong love of learning and wanting to realise that evidence is a fluid thing and that we can always evolve our understanding and develop better ways of doing things. I really wanted to try and get that link between research and improved clinical practice. Another memorable career moment was working at the Sydney Olympics. I remember going into clinics like I’m going to be working at the Sydney Olympics. Obviously, my experience working at the Institute of Sport, which I went to in 1995, and

being part of the team, building up towards that event,it couldn’t be any better. It was really fulfilling, and the athletes were amazing, because I was working behind the scenes. I had a little bit of a different role and watching the team perform from a different lens was really interesting and much more nerve wracking. Memorable moments research-wise, my first paper getting published, keynote conference presentation, really, every time you submit a paper, it’s extremely fulfilling and exciting.

How did you become a part of the ASMF Fellows?

When I came back from Qatar, I thought I might just look up and see what’s needed to apply. I looked at the criteria and I fulfilled all of them, so I applied, and I knew a little bit more

about it by that time. Craig’s been an incredible mentor of mine throughout my clinical and research. He’s been an idol of most of us, but he has had a really strong influence on me in a really positive way. Kay I’ve known also throughout my clinical career and we’ve had a really good relationship, always through just water polo. I really admire her drive and energy and she’s just a really positive person. I’ve actually nominated a couple of people to become Fellows that have been successful. I think it’s an exciting time for the Fellows and I think we have a really good opportunity to bridge that gap in research and clinical work and between the outgoing and some of the young upcoming researchers that are going to do exciting things.

What advice do you have for people starting off in Sports Medicine?

It may not be the highest paying job, involves a lot of volunteering, but I can assure you there’s nothing more rewarding than working with teams or working on projects. For me, it’s all a team sport, there’s nothing more fulfilling than achieving something together. With sports medicine, there’s so many opportunities to have a strong influence, not just on the athletes that you work with and team that you work with, but on society. Because it gives you a platform to increase selectivity and health and sensitivity to different cultures and diversity and improve happiness.

PEOPLE WHO SHAPED SMA VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022 3 3

I think it’s an exciting time for the Fellows and I think we have a really good opportunity to bridge that gap in research and clinical work.

Sports Medicine In Greece

DR. A. DELIGIANNIS, MD. CARDIOLOGIST, EM.PROFESSOR OF SPORTS MEDICINE OF ARISTOTLE UNIVERSITY OF THESSALONIKI

From ancient times, even in Greece, the home of the Olympic Games, there are many references to the relationship between sports and health. Plato, Hippocrates, Aristotle, and Isocrates are classic-era authors who refer to the role of physical exercise and nutrition in enhancing health. The first scientific report of the sudden death of an athlete has its source in Herodotus, who describes the death of Pheidippides, who, shortly before the Battle of Marathon (490 BC), ran a distance of more than 200 kilometers in two days.

University Studies In Sports And Exercise Medicine

Today Medicine is taught in seven medical schools across the country: Athens, Thessaloniki, Alexandroupoli,

Ioannina, Larissa, Patras, and Iraklion. The structure of the studies is similar in the seven schools. The Physiology course is taught in all of them, with references to Occupational Physiology and Orthopedics, which includes training in sports injuries at the undergraduate level. Nevertheless, the Sports Medicine course is mandatory proposed at a pre-graduate level in the Departments of Physical Education and Sport Sciences of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and the Athens University. Additionally, there is the opportunity to follow Ph.D. studies in Sports Medicine in all Universities. Furthermore, for Master’s studies and Master’s thesis, a postgraduate program in Sports & Health (two cognitive directions: • Sports Medicine • Exercise and Physical Health) will be available in Thessaloniki by 2015 in

cooperation with the Medical School and the Department of Physical Education and Sport Sciences of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Also, the School of Medicine of the University of Athens has been running a postgraduate program in Exercise and Health since 2000. Finally, postgraduate study programs in ‘exercise and health’ can be attended by students in the Departments of Physical Education and Sport Sciences of Thrace and Thessaly Universities.

Sports Medicine Associations

Additionally, there are scientific sports medicine Associations in the country with a significant scientific and educational contribution to the evolvement of Sports Medicine in Greece, such as the Sports Medicine Association of Greece from 2000. The

SPORTS MEDICINE AROUND THE WORLD 34 �VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022

Sports Medicine Society of Greece was initially founded in 1982, with its headquarters in Athens. Later, the Sports Medicine Association of Northern Greece was founded in Thessaloniki in 1990, and in 2000 it replaced the original Sports Medicine Society. In addition, the Hellenic College of Sports Medicine was founded in 2007. Finally, in 2018, a scientific association was created in Greece, the National Center “Exercise is Medicine-Greece.”

Sports Medicine Journals

The most prominent scientific journals in the field of Sports Medicine are “Sports Medicine,” published by the Sports Medicine Association of Greece, and “Kinesiology” by the Department of Physical Education and Sports Science of the University of Athens. In many other medical journals, papers on the subject of Sports Medicine are published. Also, several books on Sports Medicine, Sports Cardiology, and Sports Injuries have been published in Greek.

Sports Medicine Congresses

Every year major international Congresses of Sports Medicine and Conferences are organized in Greece. The biggest ones are managed by the Sports Medicine Laboratory in Thessaloniki and by the Sports Medicine Association of Greece in various cities of Greece. In addition, the FIMS World Sports Medicine Congress was organized in Athens in 2022.

Sports Medicine Studies And Research Centers

In Greece, there is no specialty in Sports Medicine. There is the specialty of a physiatrist and orthopedist who treat sports injuries. Also, several cardiologists have extensive experience managing athletes with heart disease. Physiotherapists, physical therapists, and specialist trainers deal with physical rehabilitation. In Athens, there is the National Sports Research Center, a developed Sports Medicine Center in Athens Olympic Sports Center, “Spyros Louis.” Also, the Laboratory of Exercise Physiology in the Department of Physical Education and Sport Sciences of Athens conducts some research in the field of Sports

Medicine in collaboration with hospitals in Athens. In the Department of Physical Education and Sport Sciences of Thrace University, there is a scientific center for the rehabilitation of sports injuries. Also, in Trikala, at the University of Thessaly, the Institute of Applied Physiology & Exercise in Medicine was founded in 2004 and operates with research activity in sports and health. In Thessaloniki, the Laboratory of Sports Medicine in the Department of Physical Education and Sport Sciences of Aristotle University (AUTh) of Thessaloniki was officially established in 1993. The Laboratory of Sports Medicine of AUTh is Greece’s largest Sports Medicine center (ISO 9001:2008 certified). It includes five professors and eight researchers, including sports cardiologists, exercise physiologists, and sports nutrition and cardiac rehabilitation experts. It is fully equipped for non-invasive cardiac screening of trained individuals. The research interests of the Sports Medicine Lab include: 1) Exercise rehabilitation programs in patients with chronic diseases, 2) athlete’s cardiovascular pre-participation screening, 3) biomedical side effects of doping, 4) sudden cardiac death in athletes, 5) exercise-induced cardiovascular adaptations in athletes, 6) telehealthapplications in sports cardiology. The Lab collaborates with many hospitals, medical care units, sports clubs and leagues, and European scientific centers and participates in many European Programs. Since

1993, the Sports Medicine Lab has been a pioneer in Greece in the field of therapeutic exercise, developing exercise rehabilitation programs for patients with chronic kidney disease, coronary artery disease, chronic heart failure, diabetes mellitus, and other chronic diseases, which are still unique in Greece. For the last twenty years, the Lab has coordinated rehabilitation programs for patients with chronic diseases in Municipal Gyms in collaboration with the Municipalities of Thessaloniki. More than 200 patients are exercised each year in these programs. It has also organized many International Congresses of Sports Medicine and educational conferences in Sports Cardiology and Sports Medicine. Moreover, the Laboratory organized an annual postgraduate teleconference course in Sports Medicine between Greece and Cyprus. Much research, Master’s and Ph.D. theses have been completed in the lab facilities.

Sports Medical Support For Teams

All federations and sports clubs have high-level scientific support from well-trained orthopedists, physiotherapists, masseurs, and dietitians. Furthermore, all athletes are required to undergo a cardiological examination every year to sign their health cards. Also, many Hospitals have special centers for sports injuries. In addition, CPR management teams and automated smart defibrillators are available at many venues.

SPORTS MEDICINE AROUND THE WORLD VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022 35

Sports Medicine In Greece

Useful links:

Sports Medicine Lab of AUTh: http://spmedlab.phed.auth.gr

Sports Medicine Association of Greece: http://www.sportsmedicinegreece.com https://www.oaka.com.gr

Author Bio

Asterios Deligiannis is a Cardiologist and served as a Professor of Sports Medicine at Aristotle University (AUTH) of Thessaloniki (1992-2018). Now is an Emeritus Professor of the same University (2018-today). From 1992 until 2018, he was the Director of the Sports Medicine Laboratory at the Department of Physical Education and Sport Sciences (TEFAA) AUTH, which developed into one of Greece’s largest Sports Medicine centers. He has established a pioneering cardiovascular pre-participation screening program for athletes. He has exceptional research experience on the effects of exercise training on cardiac morphology and function. A pioneering and essential activity of the Sports Medicine Laboratory under Professor Deligiannis is the establishment 1995 of therapeutic exercise programs for patients with chronic diseases, such as kidney patients on dialysis, patients with heart diseases, obesity, diabetes, etc. The work of Professor Deligiannis in the fight against doping in sports is essential. He has offered a lot to this sector through cooperation in European Programs, in educational material for young student-athletes, and from the Vice-President of the Greek National Anti-Doping Council (2005-07). He was the scientific manager or member of many research projects. Professor Deligiannis was President of the TEFAA of AUTH, Director of the Department of Sports Medicine at TEFAA, member of the Senate of AUTH, member of

the Board of the Research Committee of AUTH, Member of the Health Committee of AUTH, a founding member and President of the European Society for “Physical Rehabilitation of Patients with Chronic Renal Failure.” He was a nuclear member of the Sports Cardiology Section of ESC (2004-10) and Treasurer of EURORECKD (2000-today). He is also a member of many scientific societies. He was a founding member and President of the Sports Medicine Association of Greece (1992-2002), a founding member and President of the Hellenic College of Sports Medicine (2004-2016), and a member of the Administration Council of the Medical Society of Thessaloniki (2000-2008). He also served as Municipal Councilor and Deputy Mayor for Social Policy of the Municipality of Thessaloniki (2006-2010). He was the Chairman of the Organizing Committee of many Congresses and conferences in Sports Medicine. He has more than 500 publications in scientific journals. He has presented more than 300 studies in the area of Sports Medicine at National and International Congresses. He has been invited as a lecturer at many Sports Medicine Congresses and was Chairman (or co-chairman) at more than 60 scientific round tables. He was the primary supervisor in many master’s and Ph.D. theses. He has been awarded many times for his research. Citations (in Scopus) : 3226 (h-index 21). For his scientific and social efforts, he has been honored many times by sports and social organizations.

SPORTS MEDICINE AROUND THE WORLD 36 �VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022

Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport and sister journal JSAMS Plus Official journals of Sports Medicine Australia Open Access Also publishing • Clinical and other Case Studies • Opinion papers (“perspectives”) • Letters-to-the-Editor 4.597 1 million full text downloads per year Get noticed—publish in JSAMS or JSAMS Plus Scan here to learn more

Sports Trainer Highlight with Innalla Press

Can

I have always played Hockey and was inspired to move into Sports Training through my experience with sport. This is how I met Ross who was a presenter and we got talking about it and I was looking for a career change at the time, so I thought it would be worth giving it a go. My first step was attending several courses including pain management and concussion management before completing a Level One Sports Trainer course. I’ve always strapped myself together at Hockey but wanted to get this education to be able to help out more people in clubs and teams.

The main areas I worked on were first aid and basic strapping. Most of my role was reassuring people that they were okay and getting them back out on the field to play. We also worked across several age groups as well which presented different challenges. Towards the end of the tournament, we were working with anywhere from eight to eighteen-year olds. In your younger age groups, they can be unbreakable which is different when you get to the older players.

It was interesting working with a large range of people. We had sports trainers and physiotherapists from all over the

you tell me a little about how you got into sports training and what inspired you to pursue it as a career?

Can you tell us a little bit about your time at the recent Kanga Cup?

Were there any specific challenges to managing an event of this nature?

38 �VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022

country coming to work at the Kanga Cup, so I was exposed to several different ways of working. We would be paired together for games and areas to work as a team, so it was definitely a learning opportunity for everyone involved. For myself, it’s all about getting the players back out on the pitch, that comes from my background in sport, which not everyone has.

How has SMA helped your career so far?

I’ve found lots of job opportunities through SMA and lots of events that are available that are incredibly useful for developing as a Sports Trainer. For me especially, the support that I get from just being able to call up if I’ve got a question and people such as SMA staff member, Kaitlyn Hall, can assist. There’s also a lot of people that being part of SMA can connect you with. I know I can reach out to lecturers from courses and have that ongoing learning process.

Do you have any advice or tips for Sports Trainers who are starting out?

Take the step. If you’ve thought about it, if you’ve thought about or wanted to help your team in other ways, just do it, don’t be scared. Probably because as a team player, we’ve all had people that are always injured as if they’re not. Just take the step, just be brave. Next year I am doing Sports Science as a University degree so the opportunities that can come from this career path are numerous.

VOLUME 40 ISSUE 2 2022 39 SPORTS TRAINER HIGHLIGHT

Publisher Sports Medicine Australia Melbourne Sports Centre, 10 Brens Drive, Parkville VIC 3206 sma.org.au ISSN No. 2205-1244 PP No. 226480/00028