FEATURING

• Sport and society still haven’t found the middle ground on clean air

• Implications of jet lag and Olympic performance

• Low back pain in athletes: What do we know and what do we need to know

• Sport and society still haven’t found the middle ground on clean air

• Implications of jet lag and Olympic performance

• Low back pain in athletes: What do we know and what do we need to know

02

From the Chair

SMA Board Chair, Dr Kay Copeland, introduces the SMA Sports Doctors special interest group and other education initiatives planned this year.

03

From the CEO

Jamie Crain highlights the 2024 Member Survey results and and summarises this issue’s feature articles.

Opinions expressed throughout the magazine are the contributors’ own and do not necessarily reflect the views or policy of Sports Medicine Australia (SMA). Members and readers are advised that SMA cannot be held responsible for the accuracy of statements made in advertisements nor the quality of goods or services advertised. All materials copyright. On acceptance of an article for publication, copyright passes to the publisher.

04

Low back pain in athletes – What do we know and what do we need to know?

Dr Larissa Trease explores the experiences of elite athletes with low back pain (LBP) and factors associated with and predictive of recovery.

11

Returning to our roots

SMA’s major partner, ASICS, shares its development and innovation in the basketball space since the 1950s.

Publisher Sports Medicine Australia State Netball and Hockey Centre – Parkville 10 Brens Drive, Parkville VIC 3052 sma.org.au

ISSN No. 2205-1244 PP No. 226480/00028

Copy Editors

08

SMA 2024 Membership Survey Highlights

A summary of the survey results and our response to Member feedback.

Archie Veera and Anelia du Plessis

Marketing and Member

Engagement Manager

Sarah Hope

Design/Typesetting

Perry Watson Design

Cover photograph

ImageSource/gettyimages/ master1305

Content photographs

Author supplied; www.gettyimages.com.au

13

Implications of jet lag and Olympic performance

Dr Stephen Jasper correlates jet lag with an elite athlete’s performance, in the lead up to Paris 2024.

21

Injury Epidemiology in Police Force Recruits

Vanessa Sutton sheds light on the complex relationship between pain, injury history and persistent disability in Police Force Recruits.

18

2024 SMA & ACSEP Conference –Meet your keynote speakers

Introducing an exceptional line-up of internationally and nationally acclaimed speakers who are joining us this year to take on cutting edge science.

25

Sport and society still haven’t found the middle ground on clean air

Dr John Orchard provides an interesting take on the new definition of “clean air” and how it affects elite athletes.

30

Modifiable risk factors of paediatric Anterior Cruciate Ligament injuries: Insights from a systematic review

Theresa Heering examines ACL injuries in children aged 5-14 years and the injury risk reduction strategies that should be implemented.

35

5 Mins With: Associate Professor Clare Minahan

39

People Who Shaped SMA: Professor Evert Verhagen

42

Sports Medicine Around the World: Singapore

47

Sports Trainer Highlight: Robert Ferguson

DR KAY COPELAND, SMA BOARD CHAIR, ANNOUNCES AN EXCITING NEW SPECIAL INTEREST GROUP LED BY OUR SPORTS DOCTOR MEMBERS.

Welcome to the latest edition of Sport Health.

In April, the SMA Board of Directors met to review SMA’s Strategic Plan. The new Strategic Plan for 2024-2027 is currently in development and takes into account the diverse voices and opinions of our multi-disciplinary membership base. We look forward to launching the new Strategic Plan to members in July.

We’re excited to introduce SMA Sports Doctors, a dynamic new special interest group led by a team of dedicated sports doctor members. Among the exciting initiatives underway is the launch of our revamped website in early July, featuring the popular ‘Find a Sports Doctor’ tool. This user-friendly search engine enables the public to easily locate sports doctors in their area. Additionally, the group is developing specialised courses tailored to support the continuous professional growth of our Sports Doctor members.

With concussion an everpresent concern, we have a consistent schedule of Concussion Management online courses for our members and associates

It is wonderful to partner with ACSEP for the 2024 SMA and ACSEP Conference. The joint conference will be this year’s premier occasion for sports medicine in Australia. We have an exciting line-up of speakers organised and are thrilled to be welcoming Associate Professor Clare Minahan as this year’s Refshauge Lecturer. To find out more about her and what her presentation will encompass, be sure to read her ‘5 Mins With’ interview featured in this edition of Sport Health.

With concussion an ever-present concern, we have a consistent schedule of Concussion Management online courses planned over the next few months. This course is targeted towards medical practitioners, coaches, athletes, parents, and officials to enhance understanding of how best to support player well-being in competition and return to play.

Applications for ASMF Fellowship are now open, and I encourage anyone who is contemplating their submission to apply. The new ASMF Fellows will be announced at the Fellow’s Dinner during the Conference. I look forward to joining these celebrations with all our ASMF Fellows, both new and old.

Dr Kay Copeland

Welcome to the second issue of Sport Health in 2024.

The results of our recent Member Survey are in, and we are delighted to see some excellent feedback from members which will directly inform our Strategic Plan for FY25-FY27. Of note is the consensus amongst members that SMA’s greatest point of difference is our multidisciplinary nature, demonstrated through our comprehensive professional development program of events. With this in mind, the SMA team will continue to develop new opportunities for quality learning and connection amongst our broad membership base that are focused on ease of access, value for money, and a convenient format. We will also increase the number of events for career development, and with the help of our State Councils arrange additional networking opportunities.

It was pleasing to note that over 83% of members believed SMA is in a better place than just 12 months ago. With recent investments made in new membership systems we intend to build on this progress to ensure our program of activities and communications remains as relevant

SMA’s greatest point of difference is our multidisciplinary nature, demonstrated through our comprehensive professional development program of events

as possible. To assist with this, we encourage all members to log into the member portal to check that their details and preferences are up to date.

In a first for SMA, we are excited to announce the creation of the SMA Student Network. This special interest group will be led by members of the former Executive Committee of SEMSA, who has joined forces with SMA, to help build relevant career-focused networking and educational events for our Student Associates from all disciplines, throughout their degree years.

For our accredited Sports Trainer Associates, we are excited to

announce the forthcoming launch of our new sports trainer coverage booking system, Sports Trainer Connect. This new platform allows parties to advertise coverage opportunities on a dedicated part of SMA’s website, and SMA-accredited sports trainers will be able to review and pitch their services directly.

We are also delighted to share that SMA will once again be the exclusive provider of sports trainers at the 2024 UniSport Nationals in Canberra. Expressions of interest are now being sought and we encourage all interested sports trainers to take part.

In this issue, we have topical research presented across multiple streams of sports medicine. Dr Lari Trease focusses on low back pain presentations for clinicians working in sport, while Theresa Heering discusses the importance of paediatric ACL injuries. Dr John Orchard refines the concept of “clean air” for athletes post the COVID pandemic, and Vanessa Sutton shares injury history and key performance metrics in Police Force Recruits. Lastly, Dr Steve Jasper outlines the affect jet lag and time zones have on an Olympic athlete’s performance, as we gear up for the Paris 2024 Summer Olympic Games.

We hope you enjoy reading this edition of Sport Health.

Jamie Crain

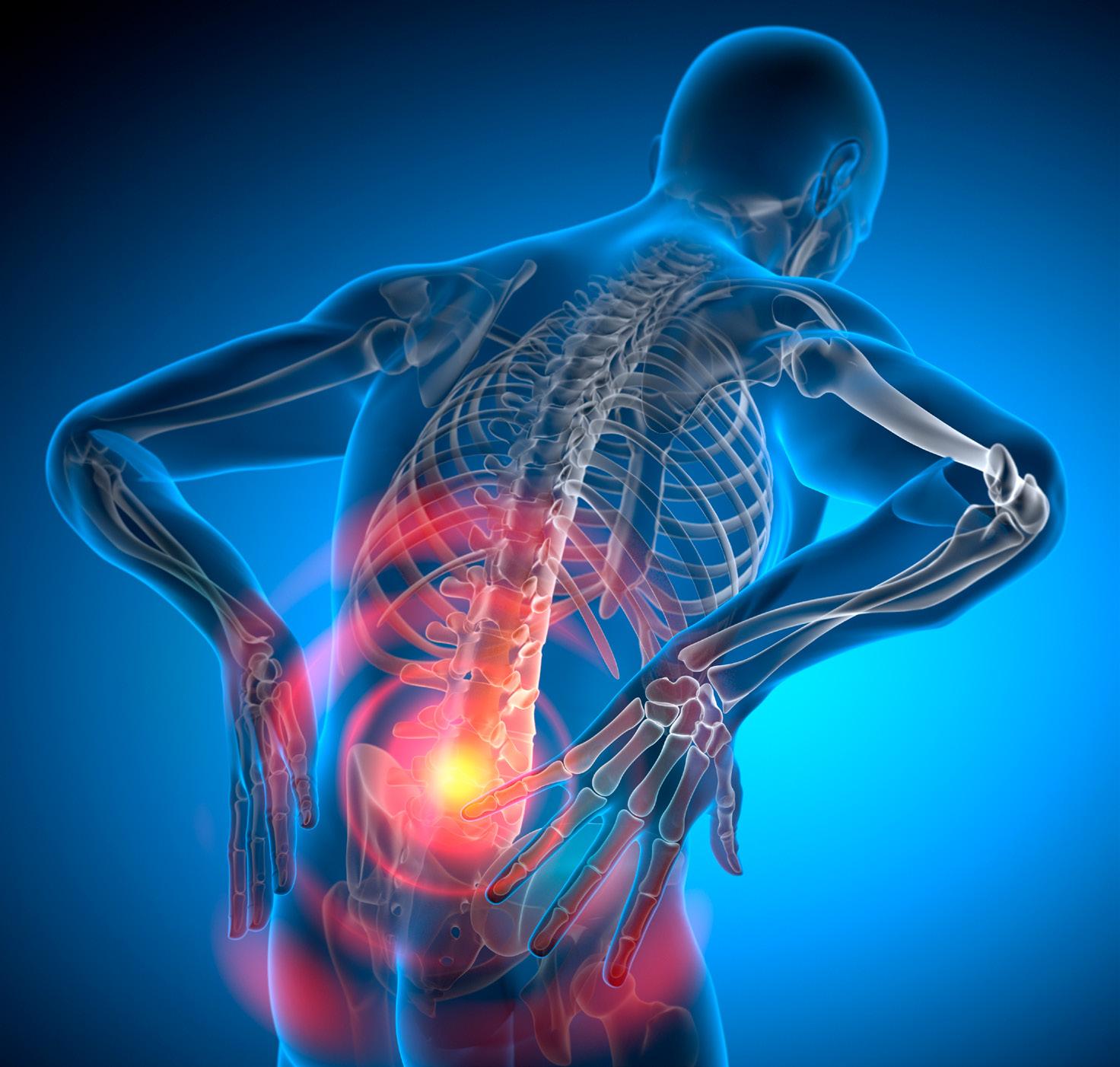

LOW BACK PAIN IS A COMMON PRESENTATION TO ALL CLINICIANS WORKING IN SPORT, AND THOSE WORKING IN PRIVATE PRACTICE WITH ACTIVE MEMBERS OF THE COMMUNITY. UP TO 90% OF OLYMPIANS WILL EXPERIENCE AN EPISODE OF LBP IN THEIR CAREER, WITH EFFECTS WHICH CAN LAST BEYOND THEIR SPORTING ENDEAVOURS.

DR LARISSA TREASE, 2022 SMA Conference – Ken Maguire Award for Best Paper in Clinical Sports Medicine

More than three quarters of Australians will experience LBP in their lifetime. While most community LBP is benign and selflimiting, Australia spends $4.8 billion per year on LBP management.

Athletes experience rates of low back pain (LBP) exceeding that of the general population. Up to a third of Olympic athletes report ongoing post-career pain and functional limitation attributed to injuries, including low back pain, sustained during their athletic careers.

Depending on the sport that an athlete is participating in, the 12-month prevalence of LBP ranges between 1% (runners) to 82% (cyclists), with sports commonly reporting a high prevalence of LBP including gymnastics, rowing and cricket. Established risk factors for athlete LBP include high or changing training volume, increased length of sporting career, and older age. Once athletes’ experience back pain, their risk for future episodes increases. Risk factors for LBP in athletes are dramatically different from those in the community, where risk factors for LBP include smoking, obesity, low

physical activity, low socio-economic status, and reduced general health.

Optimal management of athletic low back pain is poorly researched, with few randomised control trials evaluating the effectiveness of commonly used treatments for LBP in athletes. Exercise has been demonstrated to reduce pain and improve function in different athletic groups. However, the clinical applicability of this research is limited by the lack of comparison of exercise types, the use of only a single intervention when clinical practice often involves multiple concurrent

therapies to optimise recovery, and the failure to document the impact of any intervention on return to sport or performance outcomes, which are important measures for athletes and their clinicians.

Looking at all sports participants, a 2021 systematic review, published by Thornton and colleagues, on the management of LBP in athletes highlighted that the current clinical and research approach had a strong biomedical focus. This research identified that there was a paucity of research examining interventions

Depending on the sport that an athlete is participating in, the 12-month prevalence of LBP ranges between 1% (runners) to 82% (cyclists), with sports commonly reporting a high prevalence of LBP including gymnastics, rowing and cricket.

for LBP in the areas of athlete psychological or social well-being. This is despite well-established knowledge of the impact of psychosocial factors on the recovery of community members from LBP.

Specifically focussed on the sport of rowing, a Delphi study, published by Wilkie and colleagues, of experienced and expert clinicians recommended a four-phase approach to management of LBP. Key factors in the initial presentation and acute care phases

included: early identification of red and yellow flags, prompt control of pain, continued physical loading in the form of cross training, the targeted regaining of rowing-specific movement patterns, while concurrently undertaking education and empowerment of both the athlete and coach. The subacute rehabilitation and return to sport phases emphasised the need for progressively increasing on-water training volume and intensity, with concomitant reduction in crosstraining, the importance of interdisciplinary involvement in return to sport planning and the focus on ensuing any modifiable risk factors for rowing related LBP were addressed as part of secondary LBP prevention. While this was a study of clinicians with a specialist interest in the sport of rowing, both the phased approach to LBP management and the broad principles of each phase could be applied by sports clinicians to athletes participating in other sports.

Qualitative work examining rowers with LBP, published by Wilson and colleagues in 2020, highlighted that the culture and environment in which the athlete trains can be impactful on their recovery. This group identified two cultures reported by athletes: one of openness, where the coach modifies training load, the medical staff provide treatment, and the teammates provide support. This environment resulted in inclusion of the injured rower with improved self-esteem and self-efficacy and, as a result a more positive experience of LBP. Contrasting this was those rowers who reported a culture of concealment, resulting in a delay to, or failure to obtain treatment, minimal modification of training with subsequent reduced performance and a feeling of isolation, all leading to a negative LBP experience. Again, these principles can be applied by sports clinicians working with athletes in different sports and those working with active community members.

What do we know and what do we need to know?

Adolescent athletes from different sporting backgrounds who were involved in a qualitative study published in 2023 (Wall et.al.) described three themes that impacted their LBP experience: 1) the culture of normalising LBP, which the authors reported negated the safeguarding efforts that should be in place to protect adolescent athletes against pain and injury in sport, 2) the experience of LBP changed how athletes perceive themselves with increasing awareness by the adolescent of their own limits and for their need for self-advocacy and 3) the ability of an episode of LBP to impact across the other domains of a young athletes life, such as their participation at school, their daily function and their emotional health. Clinicians treating adolescent athletes in clinic and sporting environments should consider and explore these themes to optimise their patient’s recovery journey.

There is minimal research on the primary or secondary prevention of LBP in any athletic group. Perich and

Clinicians treating adolescent athletes in clinic and sporting environments should consider and explore the themes of the sporting culture, self perception and the impact on school, daily function and emotional health.

colleagues, from Perth WA, published a study focussed on adolescent female rowers (2011) which demonstrated that the prevalence of LBP at midand end-of-season can be positively influenced by screening, education, and exercise prescription across the season. This study provides clinicians with implementable tools which could help to prevent LBP in athletes.

Our recent research (presented at the 2022 SMA Conference) asked clinicians and coaches working in elite sport and elite athletes who had experienced LBP what factors they perceived were important in athletes’ LBP recovery. This group of experts identified six clusters of factors, which mapped to the well-known domains of biological, psychological and social influences of LBP recovery, a paradigm which is well established in community LBP management.

Factors in the biological domain grouped to three clusters: (i) the athlete rehabilitation journey; (ii) the athletes’ physical factors; and (iii) non-modifiable risk factors that an athlete may present with. Key recovery factors for clinicians to explore and ensure in this domain included early identification of red flags and the prompt management of serious pathologies, such as inflammatory arthropathies. Rehabilitation and return to sport planning needed to include graded exposure to optimal loading, alongside individualised plans that had measurable goals, considered the whole athlete, and addressed biomechanical contributors.

Factors in the psychological cluster including the statement rated as most important to recovery, which was “buy in from the athlete”. This cluster also included the importance of athlete

honesty about their symptoms, identifying any fear they may have about their LBP experience and their past LBP recovery experience, both positive and negative. The athletes’ mindset was perceived to be important to recovery with factors such as optimism, motivation, catastrophisation, and anxiety being highlighted by participants.

Finally, the social factors of the athlete included the two clusters ranked most important for recovery. The first was the athlete’s coach and clinical relationships, which could result in athlete empowerment. The second was the inter-disciplinary team surrounding the athlete and how this group communicated, used unifying and consistent messaging, and explained and discussed treatment options. An athlete-centred shared decisionmaking approach by this group was perceived as contributing to recovery.

The combined learnings from current research in athlete LBP highlights the importance of the environment, culture and relationships of an athlete in their recovery journey. As recommended in the systematic review on athlete LBP management (Thornton, 2022), clinicians should adopt a biopsychosocial approach when caring for athletes who present with LBP. This could involve exploring the current sport environment, stressors, and sense of agency that the athlete has, along with evaluating their mental health and supports that they can access, both clinical and social in nature.

The effectiveness of the biopsychosocial approach in helping an athlete become pain free and return to their sport is yet to be established, and Sport Health readers can contribute to our efforts to increase the research-based knowledge in this area by encouraging athletes that they work with to consider participating our ongoing research.

While most community LBP is benign and self-limiting, Australia spends $4.8 billion per year on LBP management.

We are currently recruiting participants into a prospective longitudinal cohort study: eligible athletes are aged 16 to 35, competing at the National level (national league or championships) or representing Australia in Olympic, Paralympic or Commonwealth Games sports. Athletes need to have acute LBP (<6 weeks duration) and be recruited to the study no more than 14 days following their first consultation with a health care provider. Further information for clinicians and athletes is available on our website www.athletelowbackpain.com.

For article references, please email info@sma.org.au.

Dr Larissa Trease is a Canberra based, Specialist Sport and Exercise Physician with more than 15 years’ experience in elite sport. Lari has been a team Doctor for Australian Summer (2016) and Winter (2014) Olympic, Paralympic (2008) and Youth Olympic (2012) Teams. She has had many roles within the Australian High Performance Sporting system, including providing leadership, medical care, and policy advice across three institutes of sport, and five National sporting organisations. She currently consults part-time at the Australian Institute of Sport, is the Team Doctor for the Australian Cross-Country Ski Team and a member of the World Rowing Sports Medicine Commission.

Larissa has a career-long interest in optimising medical care for elite athletes through research. She is a PhD Candidate at La Trobe Sport and Exercise Medicine Research Centre (LASEM), La Trobe University, where her research focuses on predicting the recovery of elite athletes from low back pain. She is a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) PhD scholarship recipient. Lari’s research aims to assist clinicians, coaches and athletes in elite sport to better understand the recovery trajectory and important recovery factors in athletes with LBP.

IN MARCH WE CONDUCTED OUR ANNUAL MEMBER SURVEY. ALL MEMBERS AND ASSOCIATES WERE INVITED TO PARTICIPATE, AND REPRESENTATION OF EACH DISCIPLINE WAS GENERALLY PROPORTIONAL TO MEMBERSHIP ACROSS ALL STATES AND TERRITORIES AND REFLECTIVE OF SMA’S MULTIDISCIPLINARY PROFILE.

Thank you to those members who took the time to respond. The feedback was comprehensive, and demonstrates that members have a strong connection to, and vested interest in the future of SMA.

The results have provided us with an understanding of our members’ needs, priorities, and satisfaction levels.

We’re pleased to report that 93% of the respondents are satisfied with the overall value of their membership. Nearly 30% were extremely satisfied, underscoring the real value of the professional development, content, discounts and services we offer.

An even more encouraging outcome is that over 83% of members stated that they believe SMA is performing better now than this time last year.

Members identified several services as the most valuable to their professional growth, including:

ٚ Opportunities for continued learning and skill enhancement through professional development.

ٚ Connections and professional relationships among members through networking.

ٚ Access to the latest research and industry insights through highquality journals and publications.

ٚ SMA’s Professional indemnity insurance for Sports Trainers.

Ongoing professional development remains a priority across all membership categories. Members have placed an emphasis on accessibility and convenience: more online events, including webinars, virtual workshops, and online training sessions. Additionally, there is a strong interest in high-quality, in-person events that offer valuable networking and hands-on learning opportunities.

Over 83% of members stated that they believe SMA is performing better now than this time last year.

The SMA annual Conference remains a key professional development experience, offering significant value through sessions, workshops, and networking opportunities.

Nearly 90% of respondents are satisfied with the frequency and relevance of our communications. Our weekly update emails are central to our communication strategy, as is informing and building engagement through our social channels. We will further finesse our communications to make it even more relevant to members going forward.

Members have told us that they wish to see further investment in professional development opportunities, including CPD tracking, and in-person symposia. Other member priorities include:

ٚ Enhancing ways to connect members with each other including

I joined SMA for some different perspectives fairly late in my career and have been very pleased with what I’ve learned.

- SMA Member

improved opportunities for learning, mentoring, and networking.

ٚ Advancing research and research advocacy, with better support for research initiatives, and a stronger voice in advocating for the sports medicine industry.

ٚ Establishing a clear and distinct position within the industry, especially in relation to other

associations which our members may also be members of. By clarifying our unique value proposition, we can strengthen our professional identity and better serve our members.

Sports Trainer Associates highlighted those needs critical to their professional development. They have asked for more courses that cater specifically to their career growth. Ensuring broader access to training, particularly in remote and rural areas, is essential for their continued growth and capability.

In the few months since the survey, SMA has already taken action. We have identified new projects for inclusion within our Strategic Plan, as well as several new initiatives which will boost our capabilities:

ٚ The Board has endorsed a major project to transform our Safer Sports Program delivery. This project’s outcome will deliver a more consistent and modern experience for course participants and improve our internal efficiency.

ٚ We will be launching our online ‘Find a Sports Doctor’ tool, allowing the public to locate SMA Sports Doctors within their local area. This new tool is part of a

re-launch of SMA Sports Doctors (formerly SDrA), a special interest group for medical professionals with an active interest in sports injury management and professional development.

ٚ Certificates of membership have been reinstated, with distribution to all members and associates, which will be reissued upon renewal.

ٚ Sports Trainer Connect – A new online booking system that will allow outside organisations and entities to advertise and connect with SMA Sports Trainer Associates.

Other projects we’re launching over the coming months include CPD tracking for members, and the launch of an SMA student network which will provide networking and PD growth opportunities tailored specifically to the needs of our Student and PhD Student Associates.

These are just a handful of the initiatives we have in the pipeline, all of which will enhance the overall member experience and support the ongoing professional growth of our multidisciplinary community.

We look forward to providing even more for our members in the coming months and meeting many of you at our upcoming events.

ASICS IS A LEADING PERFORMANCE SPORTS BRAND, CONTINUOUSLY DELIVERING HIGH-QUALITY, HIGHLY FUNCTIONAL FOOTWEAR FOR ENTHUSIASTS AND PROFESSIONAL ATHLETES ALIKE. THE BRAND HAS BEEN INNOVATING IN SPORTS PERFORMANCE TECHNOLOGY SINCE 1949, IN HOPES OF INSPIRING PEOPLE TO BE HEALTHY AND HAPPY THROUGH MOVEMENT.

Beyond the running arena, ASICS also produces quality sports footwear for track and field, tennis, football, netball, cricket, hockey and basketball.

The first sports athletic shoe produced by ASICS (or ONITSUKA Co. Ltd as it was known at the time) was a basketball shoe. At the time, basketball shoes were thought to be the most difficult athletic shoe to manufacture, but product was repeatedly tested and refined, until the first model was released in the spring of 1950.

Since this time, ASICS has continued to develop and innovate in the basketball space, with the brand leading the basketball footwear category in Japan.

Basketball participation rates for both adults and children continue to grow in Australia. The latest AusPlay data indicates that there is an estimate 1.11 million adults (15yrs+) and 476,000 children (0-14yrs) playing basketball. This is an increase of 1.3% in participation rates from the previous financial year and approximately 1.7% increase from prior to COVID-19.*

While participation numbers vary by age and gender, it is apparent that more and more young people in Australia are choosing basketball as their sport or physical activity of choice.

In February 2024, ASICS Oceania introduced the first ASICS Basketball shoes into the range here in Australia with the release of the Nova Surge 2 and the Gel-Burst. Additional models will be introduced in the coming seasons including the Nova Surge Low.

The Nova Surge Low basketball shoe provides energized cushioning for the aerial player and lateral stability to promote responsive transitions, while delivering excellent comfort.

The FLYTEFOAM™ Propel midsole foam provides responsive cushioning underfoot, while the lateral support in the midsole is improved through the expanded gauge at the lateral forefoot with an added PU material for side-to-side stability.

The synthetic leather in the upper is reinforced with PU material on the lateral side providing a secure hold on the foot.

To better understand the performance of ASICS basketball product in reference to popular product in the basketball market, ASICS Oceania partnered with Dr Chris Bishop PhD and his team at The Biomechanics Lab (TBL) to complete testing of ASICS products. Dr Bishop comments, “Despite the high lower limb injury rates in Basketball, the sales strategy for this footwear product category has traditionally been driven by marketing and player representation. From a biomechanical standpoint, considering the speed, high impact and change of direction demands of the sport, the players we see demand protection, without compromising agility and performance. In our opinion, that unique synergy of performance hasn’t really existed in the market to date. So, when we engaged with the consumer, irrespective of gender, the overwhelming feedback was players want a shoe that allows them to perform at their best. What that

shoe was, or its required design or features, was unknown to the player. They lacked advice. What they were dead fast on however was the shoe had to be comfortable. Comfort on court meant better performance.”

“At TBL, and in collaboration with UniSA, we have been exploring the phenomenon of footwear comfort for the best part of 10 years across a range of sports. This was our first foray into basketball. What really surprised me was the overwhelming feedback on the on-court comfort of

the range. Blinded, the Nova Surge Low consistently ranked as the most preferred shoe on comfort, agility and on-court performance compared to industry comparators. The big differentiating factor amongst player feedback, as well as in biomechanical testing, was how the shoe seemed to optimise the perception of stability and reduce the lateral thrust of force when landing and changing direction. Where 10 years ago the market felt they needed high-top designs to feel stable, intuitive geometric design seems to have leveraged and optimised the heel collar system and midsole design to provide enhanced stability to the foot, without compromising increased weight from extra shoe upper material.”

* (2023, October 1). AUSPLAY

National Sport and Physical Activity Participation Report October 2023. Clearinghouse for Sport. Retrieved May 20, 2024, from https://www. clearinghouseforsport.gov.au/research/ ausplay/results/participation-report

DR STEPHEN JASPER, The Jet Lag Guy

Introduction

With the Olympic Games in Paris (officially the Games of the XXXIII Olympiad) only weeks away, there’s a great deal of interest in maximising the performance of athletes who are competing in the games. It’s a long way from Australia to Paris, and athletes travelling there from Australia will be flying a long way, crossing multiple time zones. The difference between winning a gold medal and coming home with a silver medal is often down to fractions of a second –milliseconds – and it’s vital that they are able to perform at their peak.

Background

The Olympic Games are truly global, with host cities having been all around the world in Europe, North America, South America, and of course, twice in Australia. Often the participating athletes travel long distances across multiple time zones, and like other travellers are at risk of experiencing jet lag.

My own international travel in my previous career informed my

Jet lag tools such as Re-timer glasses or Sunnex lamps use bluegreen light to offset the effects of jet lag, while light at the red end of the spectrum has no effect on the circadian rhythm.

research, as I was employed in the pharmaceutical industry in clinical research and travelling the world. I conducted research for my PhD in jet lag and executive performance in the international business space. Typically, there is no thought of preparation for business travellers, and no or very limited support available. Yet it is vitally important that these

workers perform at their peak to facilitate international business, and simple measures can absolutely transform the effect of jet lag.

Olympic medal research

I took on the project of analysing the Olympic Games medal tallies and the effect of jet lag on performance. I began my analysis with the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome and finished with the then most recent games in Rio de Janeiro in 2016. The reason I began my analysis in 1960 was that until then, international jet travel was uncommon, and most people still travelled internationally by boat. There’s no such thing as boat lag – in order to experience jet lag, people need to travel rapidly across multiple time zones.

Analysing the data for the Olympic Games proved to be challenging, to say the least. Firstly, they are only held every four years, unlike most other tournaments that are annual. This means that for the same time period, you would only have a quarter of the data compared with, for example, the NBA.

A bigger problem is the appearance and disappearance of key nations, disqualifying a lot of the data. The Soviet Union was a behemoth in terms of Olympic medal counts until its dissolution in 1991, becoming no less than 15 separate republic that competed at subsequent Games individually. Nor was there any longer a separate East Germany and West Germany, but a single Germany after 1990.

Small countries competing at the Olympic Games would typically have volatile results – for example, the nation with the highest number of Olympic medals per capita is the tiny state of San Marino in Southern Europe, while the island nation of Tonga also punches well above its weight.

During the time period of data analysis China underwent massive cultural change, from being a non-participant in the early games to a powerhouse that hosted the 2008 Games in Beijing.

Many countries such as Australia, the USA, Russia and Canada have multiple time zones, and a decision about which time zone would be used had to be made as the starting point (in all cases, the most populous one).

Finally, there was a massive change in the number of gold medals awarded per Olympic Games, rising from 152 gold medals at Rome in 1960, to more than double with 306 at Rio in 2016. All of these factors made analysing the medal counts and jet lag challenging.

Let’s start by looking at what jet lag isn’t.

Imagine that you’re living in Sydney or Melbourne, and you’re going to travel the full length of the Trans-Siberian railway, from Vladivostok to Moscow, a journey of seven days. (I realise that now is not the time to be travelling to Russia, but let’s use this analogy.) You

board a plane in Sydney or Melbourne to fly overnight to Tokyo, a flight time of about 10 hours. Arriving early in the morning at the airport, you take a train into central Tokyo. One you arrive, you need to get to the town of Sakaiminato – half a day’s travelling and three trains away from Tokyo. You get to the ferry terminal for the boat ride to Vladivostok. Arriving at Vladivostok after 44 hours on the ferry, you clear customs and get in a taxi to your hotel. Finally – finally! – you check into your grim Soviet-era hotel. You are exhausted. You just want to jump into the shower, grab a bite to eat, and get into bed. You have a severe case of travel exhaustion.

But you are not jetlagged.

Vladivostok is in the same time zone as the east coast of Australia. While it is arduous travelling for such a long time, the time zone hasn’t changed, so there’s no disturbance to the circadian rhythm.

Now let’s contrast a second scenario – a supersonic flight from Sydney to London. The flight, which is the

If you think back to how well Australia performed at the Beijing and Tokyo Olympics (14 and 17 gold medals respectively) versus our medal tally at London and Rio de Janeiro (in both cases, 8 gold medals), you can see that our gold medal tally is approximately halved when our athletes fly long distances across multiple time zones to compete.

latest technology, only takes three hours from take-off to landing. You have a comfortable seat that you can recline in easily (first class, of course), with healthy meals and a chauffeur in London to take you to your hotel. You arrive at your London hotel refreshed after a pleasant journey.

But the jet lag will be brutal.

What has happened in the second scenario that didn’t happen in the first was a massive disruption in time zones. Our bodies run on a clock called the circadian rhythm, which is why we’re most awake during the daytime and most asleep at night, and why we don’t typically eat a large meal at three o’clock in the morning. The circadian rhythm is a biological phenomenon, involving such variables as core body temperature, metabolic rate, cortisol and melatonin levels.

To regulate the circadian rhythm, we have special receptors in the eyes in the intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells of the retina that detect light but have no input into vision.

These cells send a signal to a part of the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus, which regulates the circadian rhythm by releasing the hormone melatonin when it is dark. The word melatonin is derived from the Greek word melas meaning “black” or “dark”, which is also where we get the word for melanin, the dark pigment in the skin. The existence of these cells that detect daylght explains why many blind people know when it’s daylight, even if they can’t see it.

These cells are most sensitive to light in the blue-green part of the spectrum. Jet lag tools such as Re-timer glasses or Sunnex lamps use blue-green light to offset the effects of jet lag, while light at the red end of the spectrum has no effect on the circadian rhythm.

Having discussed the circadian rhythm, let’s now add the concept of chronotypes – because not everyone’s circadian rhythm runs the same. We talk about some people being morning people – people who naturally wake up early and have done half a day’s work before breakfast. Don’t expect these people to be the life of the party

in the evening though; they’re likely to want to be in bed well before 9 pm. Other people are what we refer to as night owls – they like to be up at the crack of noon, and don’t even think of speaking to them until their first cup of coffee. But in the evening, they absolutely come alive. This diversity in circadian rhythms is referred to as chronotypes, where people peak at different times of the day.

Age is one of the key factors that affects chronotypes, as any parent of small children will be only too aware. When you have small children, sleepins are a thing of the past. On the other hand, teenagers will make those same parents ask themselves what happened, as they struggle to get their teenage children out of bed in the morning, and their children stay up until all hours at night. There’s a general trend for people: infants and toddlers are morning people, switching to being evening people as teenagers peaking at age 17-18 years, then drifting back to being a morning person in later life.

Sex is only a minor factor, with males on average being slightly more inclined to being an evening person and peaking

in their teenage night owl behaviour slightly stronger and slightly later in life.

There is, however, a strong genetic basis for chronotype. While there are several genes that regulate the circadian rhythm, one specific gene (the PER3 gene on chromosome 1) appears to have an impact. People with a deletion in this gene are typically night owls – and there’s nothing that can be done to alter that.

Chronotype has a direct impact on jet lag because it interacts with the direction of flight, which I’ll now discuss.

The direction of flight has a significant impact on jet lag, and for most people, “east is a beast, west is best”. This makes sense when you think about it: if you fly west, the day seems to stretch out, so westbound travellers need to stay up late and sleep in the next day, which most of us find is

easy. If you fly east, however, travellers need to go to bed early (when they’re not yet tired) and wake up early (when they’re still tired), and for most of us this is much harder. This is why you often hear of people going from Australia to Europe for a holiday and experiencing little jet lag when they get to Europe, only to be hideously jetlagged when they return to Australia.

There are two completely different mechanisms to adjust to different time zones, called phase advance (for flying east) and phase delay (for flying west). To illustrate the difference between these two mechanisms, an animal study was conducted where the active ingredient in Viagra (sildenafil) was injected into hamsters in a jet lag simulation. The treatment was effective, but only for the eastbound simulation. Sadly, no human data are available.

Examining the Olympic medal counts over several decades, a couple of patterns emerged: firstly, there were

fewer gold medals for athletes as they crossed more time zones. If you think back to how well Australia performed at the Beijing and Tokyo Olympics (14 and 17 gold medals respectively) versus our medal tally at London and Rio de Janeiro (in both cases, 8 gold medals) and you can see that our gold medal tally is approximately halved when our athletes fly long distances across multiple time zones to compete.

The surprising result when I did the analysis was that the average number of silver medals increased when crossing multiple time zones. What this points to is that athletes who would otherwise have won a gold medal miss out by a small fraction, and instead come home with a silver medal.

Often the difference between a gold medal and a silver one is measured in milliseconds – so an athlete and their coach may not notice any impairment due to jet lag, until that final result.

How do you manage jet lag? There are four key cost-effective

and drug-free strategies that can reduce the deficit in performance due to jet lag:

1. Know thyself. You’ll typically know whether you’re a morning person, a night owl, or in between, and if you don’t, you can ask your nearest and dearest. Being a night owl isn’t a matter of being lazy – it’s age-related and there are genetic factors that determine your chronotype. There are some free online quizzes that clarify this, such as the Morningness Eveningness Questionnaire.

2. Direction of flight. Now that you know your chronotype, look at the direction of the flight. For most people, “east is a beast, west is best”, but if you’re very much a morning person, you’ll be the other way around, with eastbound flights being less stressful than westbound flights.

3. Scheduling. Adjust your current schedule to the new time zone as much as possible in advance. This could include arriving to your destination as early as possible. if flying west, wake up and go to bed later than usual, and if flying east, earlier. If you can give yourself a full week to scheduling before you leave, it will make adjusting to the new time zone so much easier.

4. Sunlight. As I mentioned earlier, our circadian rhythm is calibrated to sunlight, so a simple strategy of getting outdoors as much as possible will help reset your body clock. If you are scheduling to the new time zone and there’s no sunlight when you want to be awake (or you’re travelling to somewhere dark), then consider the use of artificial light sources that mimic sunlight such as Re-timer glasses or Sunnex lamp that have the frequency of light calibrated to have maximum impact on jet lag.

Clearly, there are benefits of managing jet lag for athletes who travel internationally. The number of gold medals typically gets cut in half when competitors fly across the world to compete, and these simple adjustments can make a huge difference in total gold medal count.

It is absolutely vital that athletes’ jet lag is managed comprehensively in order for them to perform at their best and potentially win gold medals. The simple, low-cost, drugfree strategies that I have outlined here could have a substantial impact on performance and abilities at the upcoming Paris Olympic Games, and I would urge athletes and coaches to do everything possible to offset the effect of crossing multiple time zones to compete. These adjustments, while only slight, can make the difference

between coming home with a gold medal versus a silver one.

I’d highly encourage you to read my detailed paper titled

“Travel across time zones and the implications for human performance post pandemic: Insights from elite sport”

Published in Frontiers in December 2022. Scan the QR code to access the article.

Dr Stephen Jasper is the director of The Jet Lag Guy, an organisation dedicated to supporting international business travellers manage and maintain their health and cognitive function. After completing a PhD examining jet lag and executive performance, he published an academic article on the effect of jet lag on Olympic medal counts.

His mission is to transform the conversation around jet lag. He has gained national and international media attention as a subject matter expert on the effect of jet lag on Olympic medal counts, with interviews with The Australian, 3AW, ABC Radio Brisbane, ABC Radio Melbourne Drive and Canberra Drive, and BBC Breakfast Radio Gloucestershire.

IN OCTOBER 2024, SMA IS CO-CONVENING OUR CONFERENCE WITH THE AUSTRALASIAN COLLEGE OF SPORT AND EXERCISE PHYSICIANS (ACSEP) AT THE ICONIC MCG. A HALLMARK OF SMA’S ANNUAL CONFERENCE IS THE HIGH CALIBRE OF KEYNOTE SPEAKERS, AND THIS YEAR IS NO DIFFERENT.

A/Prof Clare Minahan

A/Prof Clare Minahan is delivering SMA’s prestigious Sir William Refshauge Lecture.

Clare is an applied Sports Scientist with interests in the advancement of human performance and a key focus on the determinants of performance in female athletes. She applies her knowledge of female athletes to lead the development, implementation, and delivery of ‘GAPS’; an inclusive sports pathway program for emerging and parasport athletes in developing countries of the Pacific. GAPS is now formally recognised and supported by the Commonwealth Games Federation as their flagship sports development initiative for women in developing countries of the Commonwealth.

Clare’s Conference presentation focuses on the advancement of athletic performance in women and understanding their potential. There is plenty of investment in injury prevention strategies and sport participation programs for women, however sport performance research is largely ignored – only 3% of all sport performance research is performed exclusively in women. Clare will divulge how she aims to unlock new dimensions of athletic excellence and redefine our understanding of human potential, with her research in this area.

2024 VINCE HIGGINS

Dr Dinesh Palipana OAM

Dr Dinesh Palipana OAM is delivering ACSEP’s distinguished Vince Higgins Lecture.

Dinesh is a doctor, lawyer, disability advocate and researcher, and was the first quadriplegic medical intern in Queensland. He is an ambassador to the Human Rights Commission’s Includability program, a founding member of Doctors with Disabilities Australia, and an advisory board member to HealthyLife. He was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia in 2019. His autobiography, Stronger, was published by Pan Macmillan in 2022.

Dinesh co-leads the BioSpine project, which combines the most promising advances in spinal cord injury recovery, founded at centres like EPFL, UCLA and Duke University. BioSpine aims to reverse paralysis in people with spinal cord injury using thought-controlled rehabilitation, electrical stimulation, virtual reality and drug therapy.

Dinesh’s dream is to see a future where people who sustain paralysis through spinal cord injury can recover. The project is on the verge of publishing results on an initial study of five people, with a larger sample study in the works over the next couple years.

A/Prof Brent Edwards

Brent is an Associate Professor and UCalgary Research Excellence Chair within the Faculty of Kinesiology at the University of Calgary. Brent’s keynote investigates lower-extremity bone strain during locomotion and the relationship between stress fracture risk and practical alterations in training intensity, training volume, and spatial-temporal kinematics. His research may benefit runners of all levels, athletes and military personnel that participate in running activity.

A/Prof Prue Cormie

Prue is an accredited exercise physiologist whose research and clinical work focuses on the role of exercise in the management of cancer. Prue will explore how cancer patients who take exercise medicine – who perform quality exercise regularly – experience fewer and less severe treatment-related side effects, have a lower relative risk of some types of cancer recurrence, and a lower relative risk of dying from some types of cancer.

Prof Lauren Ball

Lauren has earned an international reputation for improving health of communities by creating knowledge, translating it into real life scenarios and evaluating improvements for people, health care providers and funders. Lauren will discuss the work of her research centre in Springfield QLD, with a focus on creating solutions to complex needs across diverse areas including physical activity, healthy eating, health services, domestic violence, financial wellbeing plus more.

Prof Martin Hägglund

Martin is professor of physiotherapy at the Department of Medical and Health Sciences at Linköping University in Sweden. He’s also a senior researcher in the Football Research Group (FRG) that has led a large-scale injury surveillance study in professional football in collaboration with UEFA, known as the UEFA Elite Club Injury Study. Martin’s focal research includes sports injury epidemiology, injury prevention and implementation, and return to sport protocols.

Dr Andrew Massey

Andrew joined FIFA in 2020 as Medical Director and is involved in preparing the medical infrastructure for FIFA from World Cups to grassroots football. He began his career in the game as a professional footballer and combined this with his studies in Physiotherapy. Prior to joining FIFA, Andrew was Head of Medical Services at Liverpool F.C. responsible for the medical, physiotherapy and sport science departments.

Dr Ruth Chimenti, DPT, PhD

Ruth is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Science at the University of Iowa. She has clinical experience in orthopaedic physical therapy and research training in biomechanics and ultrasound imaging. Ruth’s work focuses on the evaluation of underlying mechanisms that contribute to pain and disability in foot and ankle musculoskeletal conditions and development of their treatment strategies to optimise clinical outcomes.

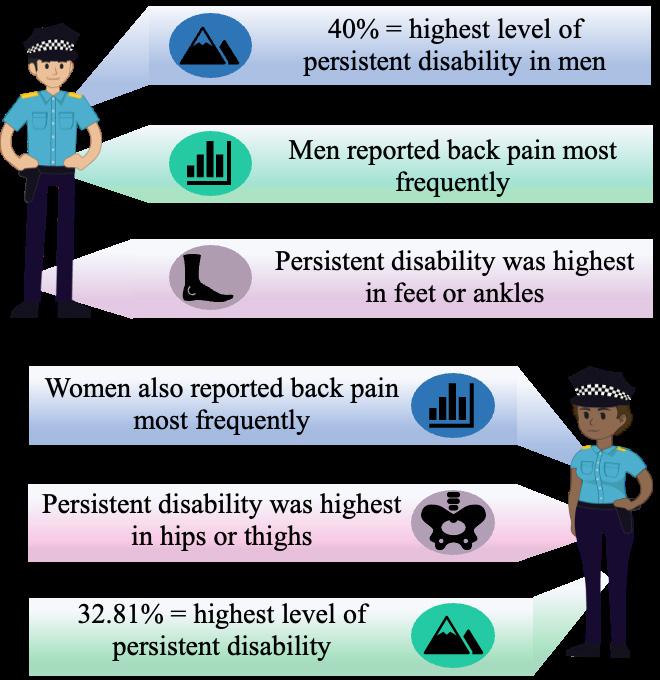

In occupational training, the rigorous demands placed on recruits, particularly within specialised sectors such as law enforcement, often serve as a crucible, testing physical and psychological resilience. My recent cross-sectional cohort study conducted on incoming Police Force recruits from January 2022 to October 2022 offers invaluable insights into the complex relationship between injury history, persistent disability, and physical performance. My research also adds to the minimal data available on law enforcement injury, pain, and performance data worldwide.

Law enforcement agencies around the globe have contended with the challenge of optimising recruit training and physical capabilities testing. Challenges include the practices and procedures of physical examinations to ensure a balance of both efficacy and safety amongst recruits. Despite stringent entry standards, the prevalence of injuries, particularly those affecting the lower limbs, continues

to be an immense problem for law enforcement agencies. Such injuries can impose individual hardship on the recruit and incur substantial costs to the government and society, considering the considerable financial investment in training a single recruit.

During Police Force training, a recruit can expect to be instructed in a diverse program of modules, spanning crucial aspects of theory to practical skills. The training regimen for many Police Force academies around the globe incorporates physical fitness sessions that involve obstacle training as well as occupational safety training, covering essential skills such as arrest and restraint techniques. Beyond the physical domain, recruits are instructed in theoretical studies, including basic fundamentals of investigative scenarios and in-depth immersion into legal studies. Driving skills for general operations and in

emergency settings, weapons training and specialised skills dependent on the location of the policing organisation, rounds out the basic skills imparted to police recruits as they are introduced to their new careers.

To ensure the capability, robustness, and resilience of Police Force recruits, rigorous tests are applied to ensure the recruits are up for the challenges that lie ahead. A commonly applied test in assessing cardiorespiratory baseline fitness is the beep-test. In this test, performance is graded, with a higher level achieved indicating better cardiorespiratory ability. Police Forces worldwide use the beep-test as well as other police-specific functional testing. While not formally validated, the policespecific functional test used in this study has been employed for over ten years. It involves a timed sprint around a track, transitioning to a second lap filled with various obstacles – balance beams, fences, walls, sand pits, hurdles, window climbs, fence scaling and

various weighted carries (e.g., kettlebell farmers walk). The faster a recruit finishes the course, the better their occupation-specific functional capacity is perceived. This approach ensures recruits are not just fit, but wellprepared for the physical demands they will face in their policing careers ahead. This component is then retested upon completion of basic Police Force training to assess their progress.

My study was conducted at an Australian Police Force Academy, where we invited recruits embarking on an extensive 28-week training program to complete a comprehensive online survey that included patientrecorded outcome measures, and we received responses from 121 recruits. Physical performance data from participating recruits were captured by physical training staff at the Police Force Academy. Key metrics evaluated included injury history within the preceding 12

months, persistent disability levels, cardiorespiratory fitness assessed via a multi-stage fitness test (commonly known as the beep-test), and occupation-specific functional capacity gauged by a Police Force specific Physical Performance Evaluation.

injury prevalence

In my study, I wanted to ascertain whether recruits had injuries or pain prior to undergoing the rigorous tests and training required to become a qualified police officer. We found that 1-in-2 recruits reported at least one

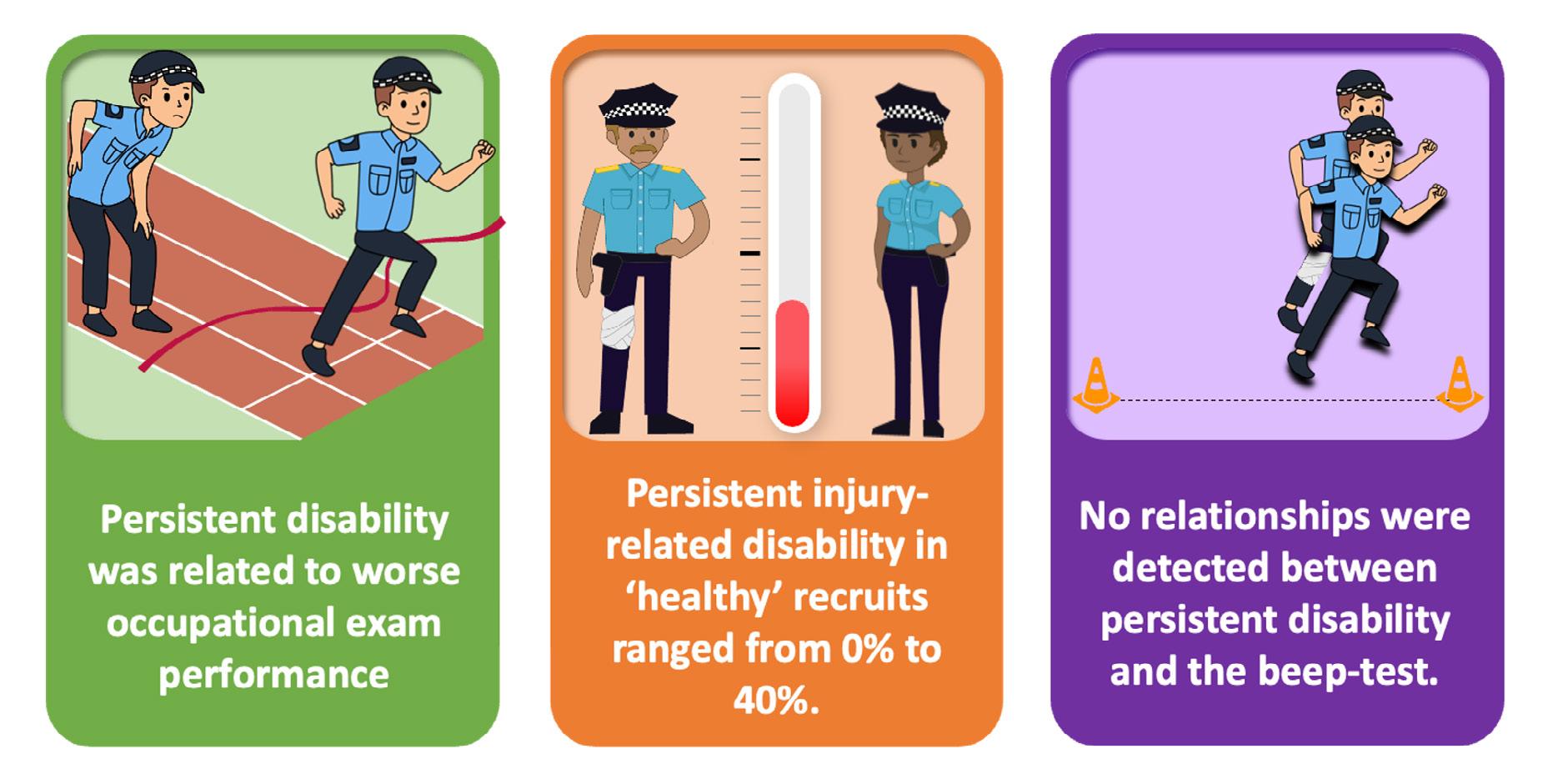

injury with varying degrees of pain or physical limitations experienced within 12 months of joining the Police Force. Further, 1-in-5 of recruits experienced more than one injury region in the preceding 12 months. Recruits who had a prior injury indicated a level of persistent disability that ranged from 0% to 40%. I also found that preacademy injuries were most frequently reported in the lower back and knees. These findings differ slightly from what is experienced during training as Police Force recruits mainly experience lower-limb and not lowerback pain during their training. This data highlights the need to expand pre-screening processes to assess how these injuries may affect performance and potentially latent vulnerabilities going into training and beyond.

The most pertinent discovery of my research for the Police Force was that a significant relationship between persistent disability resulting from pre-academy injuries and impaired physical performance in occupationalspecific tasks exists. Recruits exhibiting higher levels of persistent disability demonstrated worse outcomes in the physical performance evaluation, which is designed to encompass a range of physical challenges mirroring

real-world obstacles and physical challenges faced by those in policing and law enforcement. Interestingly, whilst persistent disability emerged as a significant determinant of timeto-completion in functional testing, its impact on cardiorespiratory fitness test levels appeared negligible.

My study’s findings convey implications for Australian Police Force training programs and overarching policy frameworks governing police force recruitment. Due to globally recognised recruitment challenges in the current employment climate for tactical-related professions (including military recruits), most Police Force entry standards around the world have been reduced to facilitate increased recruitment. However, it goes without saying it is vital that the standard of graduating Police Force officers is maintained. Thus, implementing strategies to better screen for injury history and persistent disability, with interventions designed to address this persistent disability, may improve occupational skill standards, irrespective of entrance standards.

Finally, my study’s findings underscore the necessity of revisiting existing screening protocols to incorporate more nuanced assessments capable of capturing latent vulnerabilities that might predispose recruits to injury or functional limitations. This more detailed approach would not only safeguard the well-being of the individual who is about to undertake physically arduous occupational training but also enable increased chances of operational readiness of a recruit throughout their training and onwards to maintaining public safety as a graduated Police Officer.

My study identified recruits’ persistent injury related disability before the commencement of Police Force recruit training. Thus, it is imperative to understand how persistent

disability and performance metrics influence future performance throughout academy training and academy attrition. Future studies will address these issues

Figure 3. Quantification of the performance and persistent-disability relationship

For every 1% of persistent disability

A recruit will perform the functional fitness test up to 12.34 seconds slower than an unincumbered counterpart

and further position the relevance of our findings into tangible and usable tools that will improve retention based on health and functional capacity.

My cross-sectional study amongst WA Police Force recruits sought to shed light on the complex relationship between injury history, persistent disability, and physical performance. The findings underscore the imperative of adopting a multifaceted approach, including the early identification of injuries and resulting persistent disability prior to academy commencement and introducing targeted management strategies. This would likely reduce injury risk and optimise the operational readiness of recruits to complete training and be ready to engage in full duties upon completing their training.

Vanessa Sutton, is a final-year Master of Medical and Health Science by research candidate at Edith Cowan University, with a research interest in nutrition, health and injury prevention. Following the attainment of a Bachelor’s degree in Health Science (Maj. Nutritional Bioscience) in 2021 and motivated by her personal experiences and those of her family, who have served for generations in the Western Australia Police Force, Vanessa’s research has achieved international recognition. Vanessa has been awarded both the ASICS Best Early Career Researcher Award for Sports Injury Prevention at the 2023 ASICS Sports Medicine Australia Conference, and she was also awarded the 2022 Australian Epidemiological Association’s top student prize. Vanessa brings a unique perspective to her research, shaped by nearly a decade of service in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Police. Her active military service is recognised with the Australian Active Service Medal, Iraq Medal and Australian Defence Medal.

DR JOHN ORCHARD AM, Sport & Exercise Physician

Legend has it that John Snow turned off the Broad St Pump in central London (Figure 1) in 1854 during a cholera outbreak to help clean the water supply.[1] Historians agree that he was the leading advocate of cleaning the water supply with his epidemiological study of the cholera outbreak. It is perhaps the most legendary public health action of all time. Until the water had been cleaned no one realised how dirty it was. With social discussion from the 1850s less faithfully recorded, we don’t know how many people complained about the efforts to clean the water; Twitter wasn’t around for anyone to post “my pronouns are prosecute/Snow”, but perhaps the anger and resistance to change would have been there.

Our modern concept of clean air was initially focussed on reducing air pollution (for example from car exhaust), still an important aim. In the 21st Century, we’ve needed to consider clean air from multiple new perspectives. The circulating amount of CO2 is the primary pollutant relating to global warming. Pollution from bushfire smoke became particularly relevant in Australia in 2019.[2] Then in the second year of the

COVID pandemic we appreciated that the virus was airborne and “clean air” developed an additional meaning of “air which was free of circulating respiratory viruses”.

In the modern era we have superb non-fiction writers like Michael Lewis to document the story behind the story. In the sporting world, he is most famous for writing “Moneyball” and “The Blind Side”.[3, 4] His sporting novels are similar to his finance novels (which often focus on arbitrage); Lewis’ obsession is in profiling someone or some group with inspired ideas who found a competitive advantage (a way of beating the traditional market). One exception is his book “The Premonition: A pandemic story”.[5] Whereas he normally writes a story profiling the winners and explaining why they won, The Premonition looks at how the USA (and UK) squandered their advantage in being the most prepared countries for the COVID pandemic (when they had many experts who were almost certain a modern pandemic would eventually come). The winners (namely those who found the competitive advantage) in the 2020 and 2021 years of the pandemic were actually Australia and New Zealand.[6, 7] Part of their advantage and “winningness” included that Michael Lewis wasn’t

allowed to enter either country to interview anyone in 2020 or 2021! The majority of Australians knew how well we were doing at the time (Mark McGowan as a left-wing Premier in a traditionally right-wing state of Western Australia was re-elected with a record 70% of the vote in 2021 for shutting down his state to the rest of country to keep COVID out). Australia was one of the safest countries to live with respect to mortality – in the history of the humankind – from April

Sport and society still haven’t found the middle ground on

2020 to March 2021 as we had hardly any COVID or any other respiratory viruses circulating in the community. [6, 7] [8] A recent review from The Lancet confirms that in almost every country life expectancy dropped in 2020 and 2021 with Australia and NZ being exceptions.[9] This was for a period that both seemed long (at the time) but was quite short historically. Ironically in the years when Australia and NZ were “winning” against COVID [8] it felt to many as if we were losing, because we could appreciate the loss of freedoms more than appreciate the reduction in deaths. In sporting terms though, the pandemic is now “over” in the same way that a football match is “over” if you were leading during the first half, and have now squandered that lead so badly you’ve decided to turn the TV off and no longer watch the match. The virus is now winning and our life expectancy is lower than it was in 2019 (also phrased that we still suffer “excess deaths”).

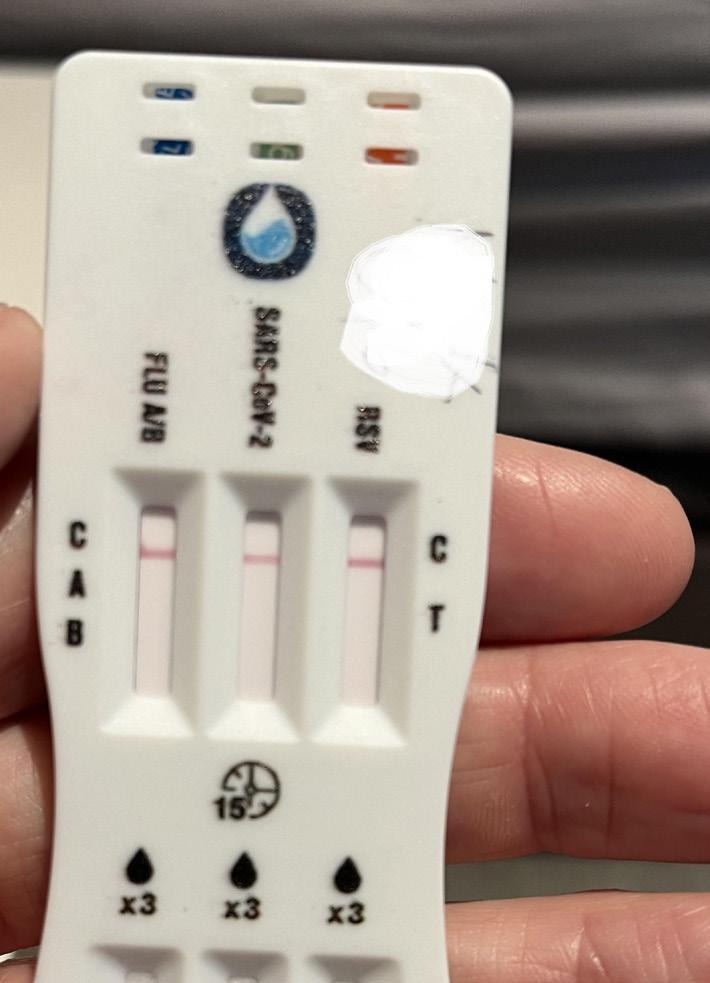

Professionally, 2020 and 2021 were very stressful years for those of us working in sport.[10, 11] On a personal level, though, I noticed one pleasant side effect. My major chronic health problem – chronic sinus infections – which I’d suffered from for 30 years, sharing them with 10% of the population,[12] disappeared completely. I used to buy sinus washout kits the way other people brought toothbrushes and toothpaste. But in 2020 and 2021 I didn’t get sinus infections, and relative to previous years, neither did many athletes.[13] I’ve noticed a return of sinus complaints in athletes in 2022 and 2023, but so far post “return to normal”, I have managed to hold them at bay with my new understanding of what “clean air” means.

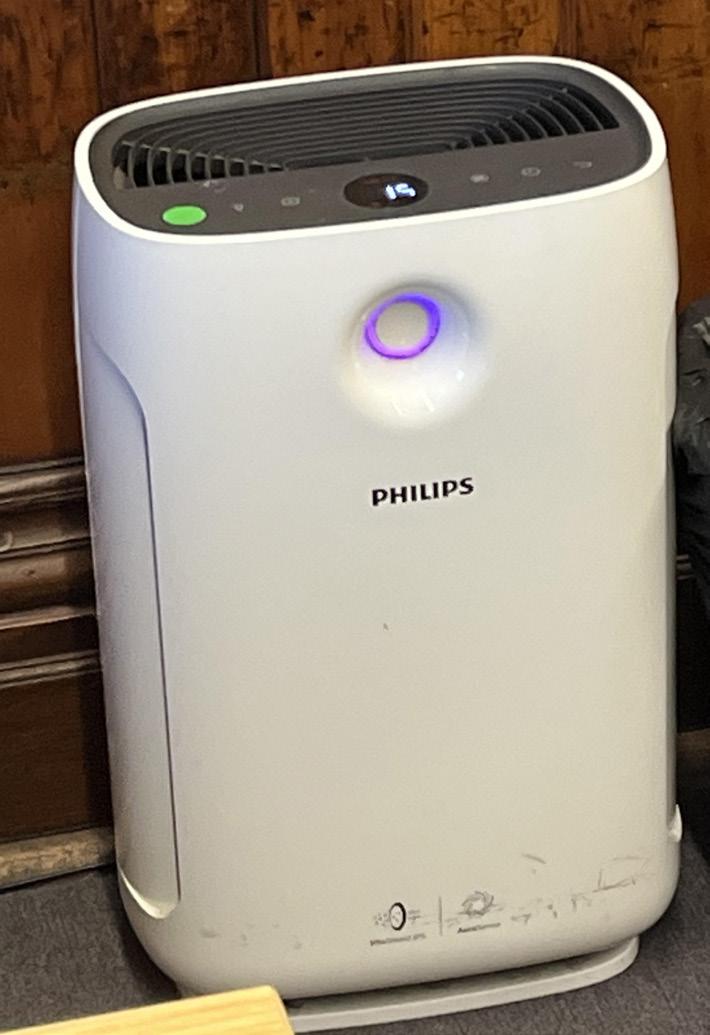

I’m now in the (maybe) 2-5% of people who still wear masks on public transport, on planes and at airports and in other crowded indoor venues (including when listening to lectures at conferences). I carry around an Aranet 4 portable CO2 monitor to work out when I might need to mask up. When I work in the clinic I still mask up and

keep the window open to circulate air (which brings the CO2 readings down from 1500 to 600, Figure 3).

If someone in our house gets a sore throat or runny nose, we still use RATs and we still isolate anyone ill. Other people don’t want to bother and perhaps don’t need to bother, because they weren’t sufferers of chronic sinus problems like I was; and they don’t have cancer, and aren’t immunosuppressed or just elderly. But in the field of Sport & Exercise Medicine, where our athletes are healthy and “over COVID”, there are still reasons we should bother a bit more than we are currently (in 2024, which for those counting is year 5 of the pandemic but a year since the end of the emergency phase was declared).

Sports medicine (and other) conferences

At least two recent Australasian sports medicine conferences since we “opened back up” have turned out to be superspreader events in terms of both COVID-19 and Influenza A. Are sports medicine conferences any different to other mass gatherings

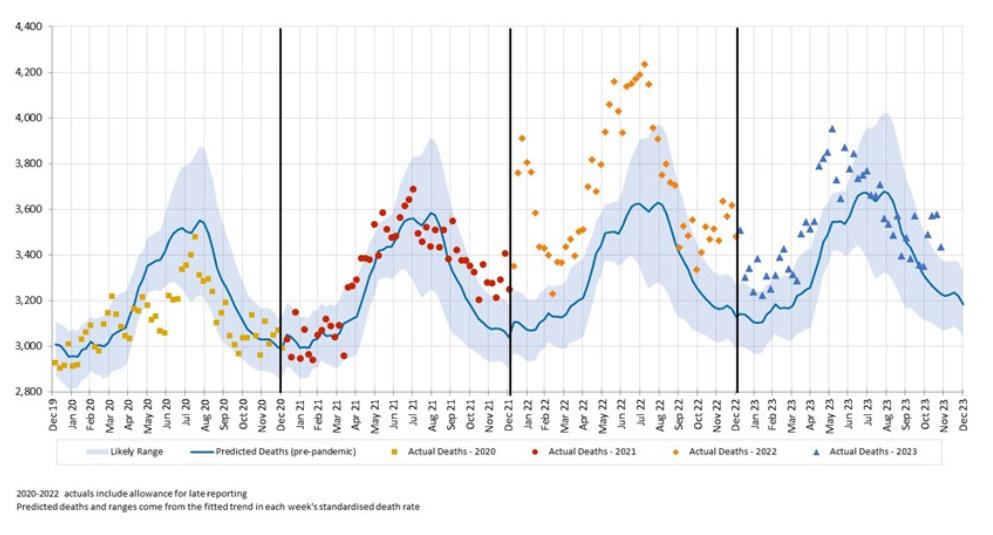

Figure 2: Expected versus actual deaths Australia for 2020, 2021, 2022 and 2023 (reproduced from www.actuaries.digital/2024/03/04/ excess-mortality-for-2023-likely-to-be-about-half-of-2022/)

where dozens fly in from multiple different venues? Perhaps it is just that Australian SEM physicians are now so familiar with respiratory diagnosis[10, 11] we are amongst the last remaining groups that could still be bothered to test (even if not bothered enough to mask). In the days before we knew any better, people used to complain about “the air conditioning” in hotel rooms causing blocked noses and

sore throats. Now we realise it is almost certainly a high percentage of conference attendees catching whatever respiratory viruses are circulating (as if you’ve spent thousands of non-refundable dollars to attend, people don’t tend to “stay home when sick”[6]). We are now realising that in the absence of precautions a high percentage of conference attendees will catch COVID (again) as

a cost of attending. So this is a clear challenge as to how we can keep conferencing without the tax of high risk of getting a respiratory illness.

When can elite athletes “afford to get sick”?

Professional athletes bore some of the worst psychological impacts of the lockdown years,[14] with some Australians athletes having to do 14 days of hotel quarantine on 5 or more occasions over 2020-2021. Understandably, as a group they are well and truly “over” what they went through in these years and some are too traumatised to even discuss any ongoing COVID precautions. Yet denial can’t escape anyone from two unarguable facts: (1) That COVID is still circulating and if you live a “normal” life you’ll inevitably catch it again; (2) That even though you are now allowed to compete/play while COVID positive, that it only has one possible effect on your athletic performance and that is to reduce it. It’s a challenging question (for team selectors) as to whether a superstar with COVID will perform better than a fringe player who is

Sport and society still haven’t found the middle ground on

COVID-free. It is a fact, not a question, that the superstar’s performance will only potentially be worse, not better, if competing/playing with COVID. Athletes love to use the cliché of “doing the one percenters” to try to get better, and wearing a mask on a crowded plane, for example, absolutely is a one percenter (in both senses – that it improves your chances of performing well at your destination, and that only about one percent of athletes could be bothered taking this performanceenhancing measure). Doctors arguing with athletes that they should consider masking all the time in crowded venues are not currently going to win very often, but it is worth considering when this argument might be won. On the way to compete in an Olympic Games, for example, where you get one shot every four years. That would make a lot of sense. In the lead up to a Grand Final (where statistically you are doing well if you manage to play in one every fourth year of your career).

A State of Origin match, maybe. Your International or first grade debut match. NASA put its astronauts into quarantine in the lead up to shuttle launches because they “couldn’t afford to have anyone sick” after they had been blasted into space.[15] Athletes need to ask themselves “when can I afford to get sick?” That is the time when you don’t need take precautions. When you can’t afford to get sick, you should be taking some precautions (and if you lived in Australia and New Zealand in 2020-21 you know what they are and which ones can still be done with minimal inconvenience).

The specialty of sport and exercise medicine has been surprised in two different directions in the past few decades. The bad news is that the majority of medical interventions, where investigated, have been shown not to work.[16, 17] The good news is that an exercise-based intervention (the signature treatment of SEM) works not only for treating many presentations,

but has the side-effect of decreasing all-cause mortality (improving longevity). Many SEM physicians have added dietary advice to their exercise advice as our clientele moves towards patients seeking the healthiest possible lifestyle specialist advice. It makes sense for us to consider “clean air” advice for patients, given it is now evident that avoiding respiratory viruses also increases longevity. [6,

The realities that we get more respiratory viruses in winter which explains the higher death rates every winter, along with the fact that Japan – with a mask-wearing and clean-air culture – has higher life expectancy than any other large country tell us that clean-air is a universal good like regular exercise. The differential death rates from Australia in 2020, 2021 compared to 2022 and 2023 should beg the question to everyone interested in health: do you want to be breathing the air that causes you to live longer (virus-free) or causes you to die quicker (containing viruses)?

Can capitalism provide the disruption?

Almost all of the heavy lifting at cleaning the air during 2020-21 was done by governments, usually against the resistance of business. Now that the population has swung from being a clear majority interested in clean air to being a clear majority no longer interested, the governments in Australia and New Zealand are unlikely to legislate to assist with cleaning the air. Are we stuck with dirty air for good? There may be a way out.

Imagine the hypothetical of a highrise hotel that has two sections. To be eligible to stay in a room in the top ‘x’ (“green”) floors, the hotel institutes a rule that you need to submit a negative RAT every day for COVID and Influenza, and if you have any cough or runny nose (despite testing negative) you need to wear a mask when outside your room. In the bottom ‘y’ (“orange”) floors, it is business as usual, so that if you tested positive for COVID or started coughing profusely staying in one of the green floors they’d just refund your money and offer to rebook you into one of the orange floors. In addition, the hotel would apply the same policies to their staff, so that a staff member who tested positive would only work in the orange floors and you’d have a

guarantee on the green floors that all room cleaners, waiters and bartenders were free from respiratory viruses.

The big question is what would happen to a hotel who decided on a mixed policy and how many green floors would there would end up being and how many orange floors would there end up being? A hotel that did some market research would soon find that there might be a market for the green floors for people on business or holiday that were well and “couldn’t afford to get sick”. But in running such a mixed policy, they would be drawing attention to their orange floors being full of customers and staff with COVID and other respiratory diseases. It might sound like a bad idea for a hotel to split

their floors like this until they realised that they might not be under any obligation to provide the orange floors, as that is the service every other hotel currently provides. In other words, in Australia and New Zealand in 2020 and 2021 (due to government legislation), every hotel was a “green” hotel and anyone who wanted an orange hotel couldn’t have one. But from 2022-2024, every hotel is now an orange hotel and no one is servicing whatever market there is for green hotels. Neither is anyone offering green airline flights or green function centres or green cruise ships. The challenge for capitalism is to answer: why not? It isn’t everyone’s cup of tea to go back to doing RATs, but maybe cancer patients, doctors attending a conference and athletes about to play in a Grand Final might be some of the groups who could form the basis for such a market.

The biggest advances of capitalism come from developing a product that the consumers didn’t previously realise that they wanted. The product road testing for green hotels or green airline flights was all done in 2020 and 2021. If there were companies out there brave enough to offer such a product, would anyone want to buy it? The marketing should be obvious: “Can you afford to get sick? If not, stay/fly/eat here”.

For article references, please email info@sma.org.au

John Orchard is a Sydney-based Sport & Exercise Medicine physician. Opinions expressed in this article are personal. The main conflict to declare is having personally been a chronic sinus infection sufferer prior to 2020 but having been remarkably infection-free since pandemic measures were introduced.

THERESA HEERING, 2023

ASICS SMA Conference –ASICS Best Poster in Sports Injury Prevention

Why is it important to research paediatric ACL injuries?

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries have severe consequences for the individual (e.g., long rehabilitation phase, risk of less future physical activity participation) and the health care system (e.g., high treatment cost) and are reported at increasing rates in children aged 5-14-years1. In Australia, females aged 5-14-years displayed the highest annual injury growth rates of ACL injuries compared to same aged boys (10.4% girls vs. 7.3% boys) but also older populations aged 15-44 years. 2 Thus, risk reduction approaches considering children’s unique needs are warranted to address the increasing risk of paediatric ACL injuries. 2

What to do we know about paediatric ACL injuries?

We know that most paediatric ACL injuries occur in sport settings during either organised (e.g., team sport, such as soccer) or non-organised, recreational activities (e.g., outdoor play, backyard trampoline). 3 However,

the actual injury mechanism (e.g., body position at time of injury) in this age group is not well understood and assumed to be similar to the injury mechanism observed in adolescents and adults.4 In adolescents and adults, ACL injuries occur most commonly in situations without body-contact, shortly after initial ground contact during landing or running related movements with sudden change in direction (e.g., a side-cutting

movement) or deceleration. An injury occurs when the load on the ACL is too high. When analysing a series of adult ACL injuries, it seemed that ‘axial compression force’ is the primary force responsible for non-contact ACL injury. 5 Additional movement characteristics such as a strong activation of the quadriceps muscle group or a medial displacement of the knee may increase the loading of the ACL and lower the force threshold for ACL injury. 5

How can individuals at risk be identified?

In Australia, females aged 5-14-years displayed the highest annual injury growth rates of ACL injuries compared to same aged boys.

For adolescents and adults, risk identification is based on examining factors that were previously mechanically linked to ACL loading (e.g., quadriceps muscle force). Risk factors are often classified as internal risk factors that are inherent to an individual such as anatomical or biomechanical factors, or external risk factors that are outside the

influence of the individual (e.g., weather, equipment). Of particular interest for effective risk reduction approaches are risk factors that can be modified through interventions –so called modifiable risk factors (e.g., biomechanical factors). To identify such risk factors, a variety of physical screening tasks and movement analysis strategies can be used. However, risk reduction approaches are often designed for adolescents and adults and lack specificity to children’s unique development.

In my PhD research, I wanted to understand modifiable risk factors and their assessment in paediatric populations. I conducted a systematic literature review and aimed firstly, to identify the modifiable factors mechanically linked to an increased risk of paediatric ACL injury and secondly, to determine the physical screening tasks and data collection tools used to examine modifiable risk factors in children aged under 14 years. The results of the systematic literature review were published as academic article (reference provided below) and presented as a poster at the 2023 Asics SMA conference.

What did the systematic literature review reveal?

The majority of the 40 eligible studies examined modifiable risk in regard to ACL injury risk in girls aged 10–13 years. These studies mainly focused on intrinsic risk factors as opposed to extrinsic risk factors. Similar to

Modifiable risk factors of paediatric