MARCH 2023 Popping the Bubble of Positive Psychology + How Do (or Don’t) You Cope? Daze of Future Past PG. 26 PG. 28 PG. 38

Need a summer job? Apply at Dominos.com or stop by the store

Part-time, full-time job openings with VERY flexible schedules!

Domino’sTM SUN-THURS: 10AM - 2AM • FRI-SAT: 10AM - 3AM WE MAKE ORDERING EASY! CALL DIRECT OR CHOOSE YOUR ONLINE OR MOBILE DEVICE 215-662-1400 4438 Chestnut St. 215-557-0940 401 N. 21st St. OPEN LATE & LATE NITE DELIVERY

Dominos.com or stop by the store

full-time job

with VERY flexible schedules! Domino’sTM SUN-THURS: 10AM - 2AM • FRI-SAT: 10AM - 3AM WE MAKE ORDERING EASY! CALL DIRECT OR CHOOSE YOUR ONLINE OR MOBILE DEVICE 215-662-1400 4438 Chestnut St. 215-557-0940 401 N. 21st St. OPEN LATE & LATE NITE DELIVERY

Need a summer job? Apply at

Part-time,

openings

Contents

March

Being a student at Penn starts off benign, until there’s a moment of sinister absurdism, and you come out totally wrecked on the other side.

EXECUTIVE BOARD

Walden Green, Editor–in–Chief green@34st.com

Arielle Stanger, Print Managing Editor stanger@34st.com

Alana Bess, Digital Managing Editor bess@34st.com

Collin Wang, Design Editor wangc@34st.com

EDITORS

Avalon Hinchman, Features Editor

Jean Paik, Features Editor

Natalia Castillo, Assignments Editor

Kate Ratner, Assignments Editor

Anna O'Neill–Dietel, Focus Editor

Naima Small, Style Editor

Norah Rami, Ego Editor

Hannah Sung, Music Editor

Irma Kiss, Arts Editor

Weike Li, Film & TV Editor

Rachel Zhang, Multimedia Editor

Kayla Cotter, Social Media Editor

THIS ISSUE

Julia Fischer, Copy Editor Deputy Design Editors

Wei–An Jin, Ani Nguyen Le, Sophia Liu Design Associates

Heaven Cross, Raymond Feng, Erin Ma, Janine Navalta, Allyson Ye

STAFF

Features Staff Writers

Katie Bartlett, Delaney Parks, Sejal Sangani

Focus Beat Writers

Leo Biehl, Dedeepya Guthikonda, Sara Heim, Sophia Rosser, Rahul Variar

Style Beat Writers

Layla Brooks, Emma Halper, Alexandra Kanan, Claire Kim, Felicitas Tananibe

Music Beat Writers

LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The Land on which the office of The Daily Pennsylvanian stands is a part of the homeland and territory of the Lenni-Lenape people. We affirm Indigenous sovereignty and will work to hold the DP and the University of Pennsylvania more accountable to the needs of Indigenous people.

CONTACTING 34th STREET MAGAZINE

If you have questions, comments, complaints or letters to the editor, email Walden Green, Editor–in–Chief, at green@34st.com You can also call us at (215) 422–4640.

www.34st.com © 2023 34th Street Magazine, The Daily Pennsylvanian, Inc. No part may be reproduced in whole or in part without the express, written consent of the editors. All rights reserved.

Kelly Cho, Halla Elkhwad, Ryanne Mills, Olivia Reynolds, Mehreen Syed

Arts Beat Writers

Jojo Buccini, Jessa Glassman, Eyana Lao, Giulia Noto La Diega

Film & TV Beat Writers

Alex Baxter, Mollie Benn, Kayla Cotter, Emma Marks, Isaac Pollock, Catherine Sorrentino

Ego Beat Writers

Sophie Barkan, Noah Goldfischer, Ella Sohn, Vikki Xu

Staff Writers

Morgan Crawford, Heaven Cross, Angele

Diamacoune, Rayan Jawa, Enne Kim, Jules

Lingenfelter, Luiza Louback, Dianna Trujillo

Magdalena, Yeeun Yoo

Audience Engagement Associates

Annie Bingle, Ivanna Dudych, Yamila Frej, Lauren Pantzer, Felicitas Tananibe, Liv Yun

CAMPUS 7 Ego of the Month: Jerry Gao 10 Breaking the Fourth Wall: Pennfluencers Tell All CULTURE 42 Why Does it Matter Who Gets the Oscar? 48 Laughing Gas and Landscapes: The Mystery of a Lost Courbet CITY 18 A Reverberating Victory: Shut Down Berks and the Fight for Immigrant Liberation YOUR BRAIN ON UPENN 24 Hustle Culture and the Rise of Toxic Productivity at Penn 26 How Do (or Don’t) You Cope? 28 Popping the Bubble of Positive Psychology 32 Social Media is Telling Us How to Be Sad 38 Daze of Future Past

2023

Slaw ON THE COVER

Pictured: Arielle Stanger, Cover Photos by Anna Vazhaeparambil, Styling by Emily White, Design by Collin Wang

At the beginning of last semester, I started Prozac. That’s the brand name of fluoxetine, which is an SSRI—selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Pretty much my brain either doesn’t make enough serotonin, or takes it back up from the synaptic cleft too quickly. My psychiatrist didn’t test for any of this when I met with him; he knew I had a family history of depression, and asked me to describe how I felt in one of my lows.

I told him there was a sadness there, but not the sharp, cathartic kind, accompanied by hopelessness about my own future and the kind of existential dread that makes it hard to tell whether humans have always felt this way or if that’s just what late stage capitalism wants you to think. The depression didn’t come from nowhere; it would start with a reminder—that I was more single or less accomplished than I’d wanted to be—that would balloon out until I had to ask if normal people got this miserable about the same things.

He decided Prozac and I were a good fit.

Before anything else, there were the side effects. I got really tired, but whenever I slept I’d have these multi–night stress dream marathons. The first few weeks featured daily bouts of derealization, which means that the world felt suddenly dreamlike. When the meds finally started to work as intended, it was hard to notice them. The effects just weren’t

hitting me as hard as they used to, and my “recovery time” went down from days to maybe a day at most.

There was a problem though: I was still sleeping through my lectures, and my verve for working hard in classes with less–than–inspiring profs had yet to bounce back. A kind of fundamental shift had happened. Without the looming threat of a grade–induced depression, grades didn’t seem as important. Somewhere along the way, I shifted from a primarily fear–based motivation to one that was driven by passion.

People love to throw around the phrase, “Prozac Nation,” as a scare tactic, conjuring images of a lobotomized society too Xanned–out to feel anything. But the original Prozac Nation, a 2001 cult classic starring Christina Ricci (j’adore), has the opposite message. The film is set in the pre–medication ‘80s, following a Harvard student named Lizzie—in an uncanny bit of coincidence, she’s also a music writer—as she spirals out of control, choosing every wrong option to cope with her instability.

I was worried, in a way that a lot of people are worried when they start psychiatric treatment, that I’d become dull—a shell of the former self who loved that I could relate to Fiona Apple because we both felt too much. Of course, I needn’t have been. My brain just needed a little recalibration.

This issue is called ‘Your Brain on UPenn,’ but it’s not really about the havoc Penn wreaks on your psyche. These stories begin after the damage has already been done, and ask how we can recalibrate our minds to reach some semblance of our former selves, or emerge on the other side a new, more whole version. Some of us turn to comfort shows or cut our own bangs, while others rewire their brains with psychedelics. Our feature explores the doctrine of positive psychology, certainly the healthiest approach, but perhaps not as much of a panacea as it’s cracked up to be.

If there’s one thing our staff learned putting this package together, it’s that not everyone needs Prozac, but everyone needs a way to cope. When you look at it that way, antidepressants don’t seem so bad anymore.

34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 4 Airle l e S t a n g e r LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

Going on antidepressants completely recalibrated the way I think about college, and it might not be the worst thing if we all became more of a Prozac Nation.

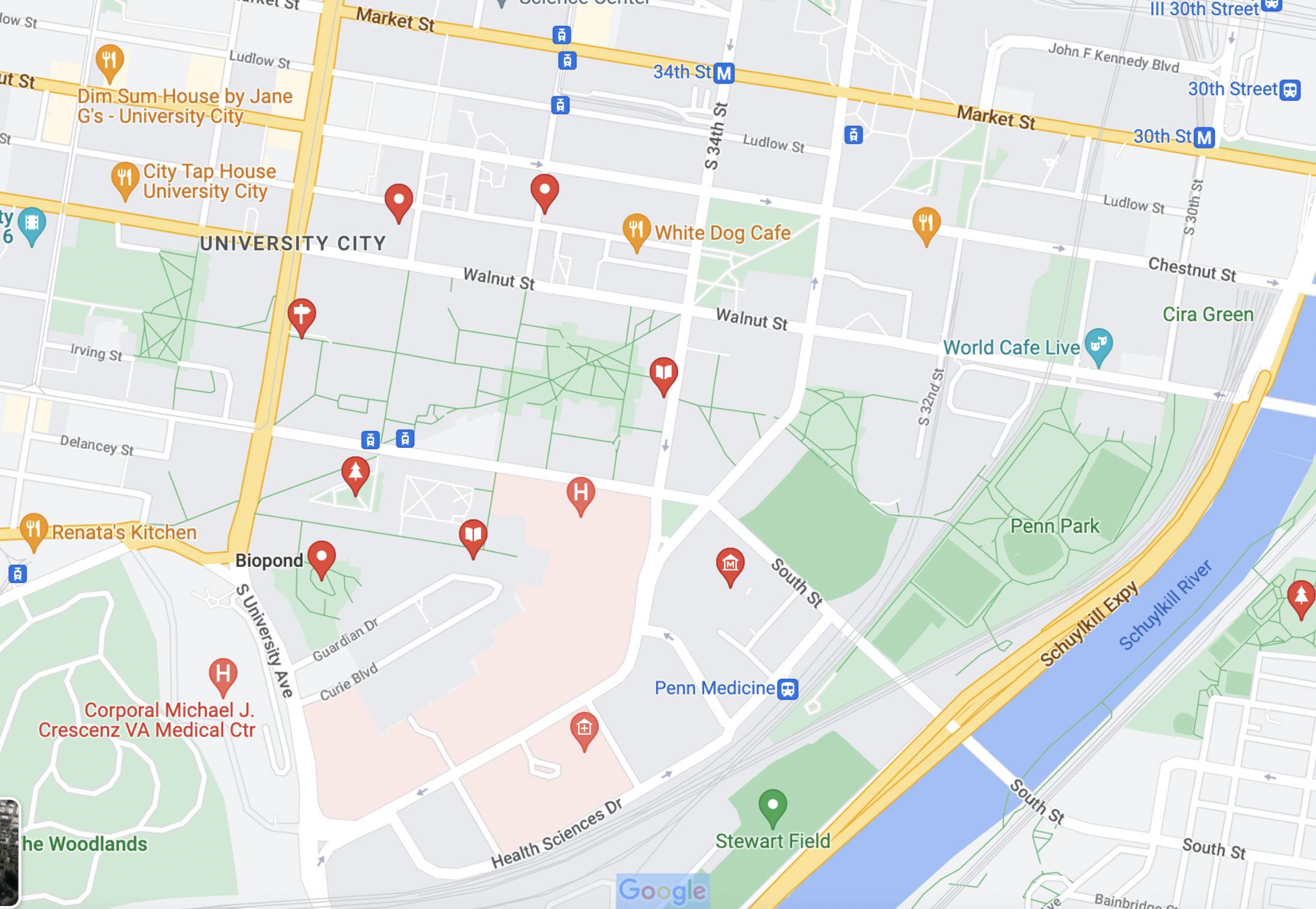

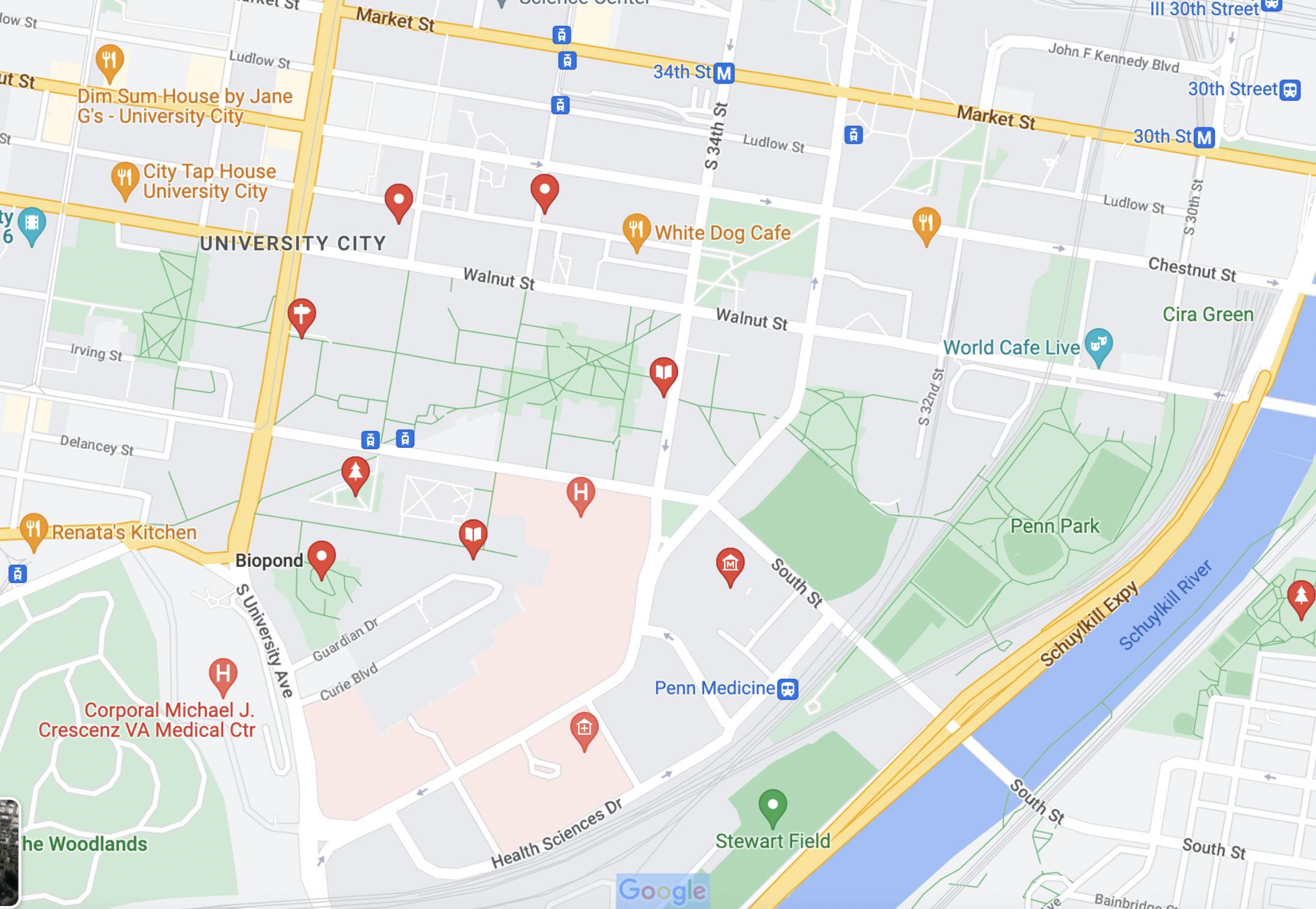

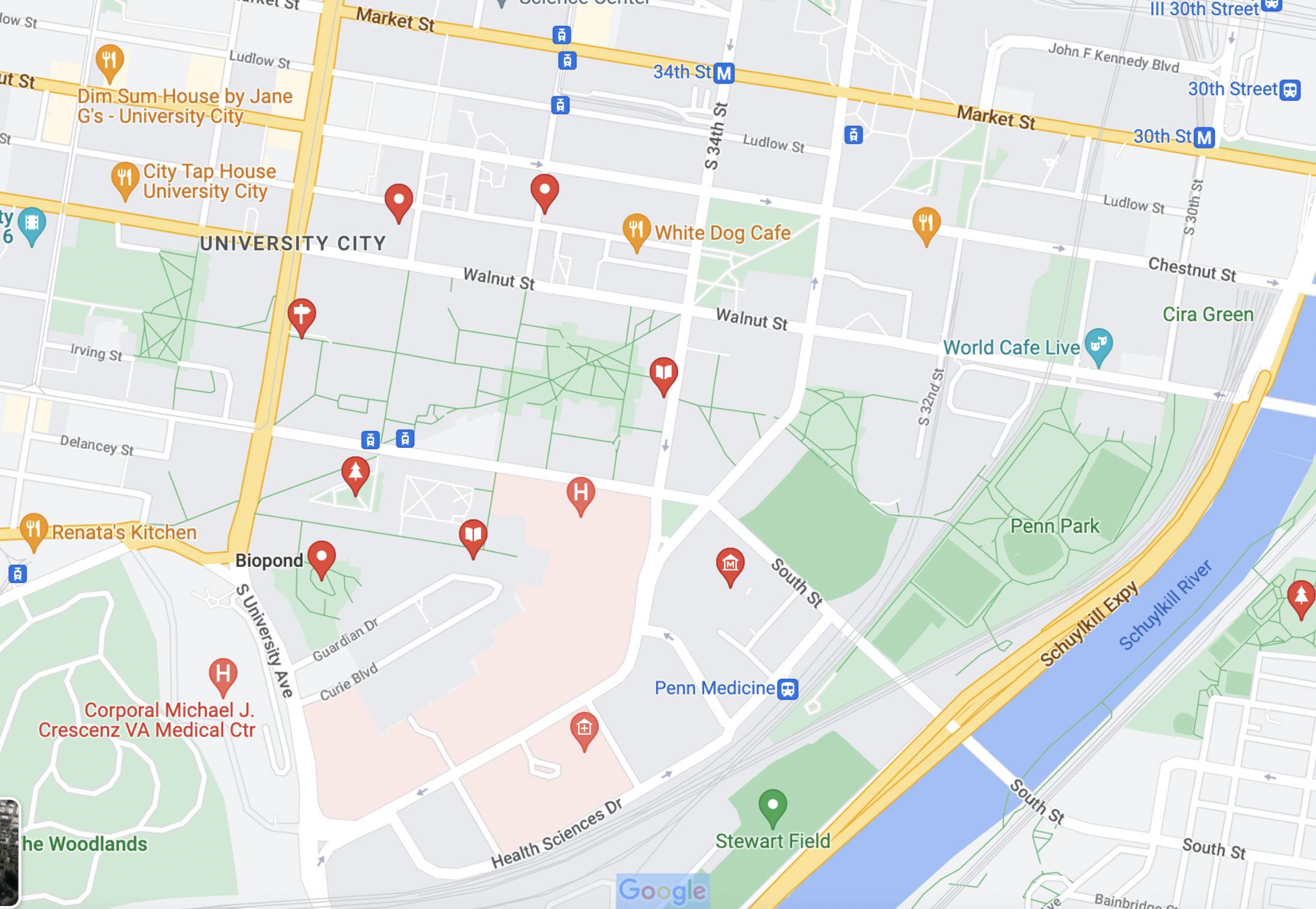

Of the 3,404 students admitted to Penn’s Class of 2024, 168 of them hailed from the city of Philadelphia. While it is highly unlikely that every Philadelphia admit accepted their offer of admission from Penn, it can be assumed that around 5% of the 2,400–person junior class possesses the unique perspective of attending college in the same city where they reside based on the number originally admitted. Statistically speaking, then, being included in this percentage is a rarity on this campus.

I am part of that 5%. Whether it’s the 19145 zip code on my driver’s license, the 215 area code at the start of my phone number, or my mispronunciation of words like “water” or “bagel,” there’s no mistaking that I grew up in the city that

From Philly to Philly, the Long Way Around

Why staying close to home for college can be both a blessing and a curse.

BY ALLYSON NELSON

BY ALLYSON NELSON

MARCH 2023 5

CAMPUS

Illustration: Collin Wang

most Penn students had never stepped foot in before enrolling.

Some days, being a Penn student from Philadelphia is a tremendous blessing. Others, it’s my greatest curse.

The differentiation between positive and negative in this situation lies within the distance between the life I’ve always known and the life I began when I became a Penn student. While some people have to travel across the world to come to Penn, my house is a mere 3.9 miles from my apartment. I watch my best friends from Los Angeles, northern Virginia, Chicago, and even New Jersey learn how to navigate the ups and downs of independence for the first time, knowing that I will never be able to experience that during my time as an undergraduate. While my peers tell me that I could easily do the same, they forget that the decision isn’t that simple. When the people and places that have created my happiest memories are always within my grasp, I can’t bring myself to stay apart from them.

Like clockwork, one of my parents picks me up every other Friday to spend the weekend sleeping in a bedroom that’s

only ever belonged to me. As Interstate 76 rushes by my eyes on the drive home, I stare out the window, wondering if I made the right choice when I committed to Penn. Wondering if I should’ve pushed myself out of the world I’ve always known instead of making the comfortable decision. Wondering if I would have been a different person—more importantly, a better person—if I had left Philadelphia.

someone—and in turn, becoming a disappointment myself.

In this contemplation, however, I realize how much of a privilege it is to be so close to home during college. In the past year alone, I got to attend the World Series and watch my hometown Phillies play in the fall classic for the first time in 13 years, embark on impromptu weekend trips with my sister, take my friends to the New Jersey shore town where I’ve spent every summer of my life thus far, and watched my 3–year–old godson grow up right before my eyes. When I finally caught COVID–19 last April, my parents promptly brought me a care package that would have lasted for five quarantines instead of one. I could see the bridge right by my house from my dorm room window sophomore year when others could only see their hometowns in pictures. And throughout my time at Penn, I’ve never felt homesick. Ever. It would be impossible for me to.

The constant “what ifs” that plague my mind as a result of the decision I made almost three years ago drive me, in all honesty, to the brink of insanity. My tendency to overthink everything I do escalates these thoughts from simple worries to pure paranoia. Turning down invitations to spend time with friends because it’s a weekend at home fills me with immense guilt. Seeing snapshots of my Penn counterparts experiencing something new every Saturday makes me question my role in Penn’s social scene. And when I tell my parents that I’m not coming home so I can spend time on my own, I fear that they presume I want nothing to do with them. In summary, no matter what decision I’m making, I feel as if I’m disappointing

Despite my senior year rapidly approaching, my dilemma is far from over. As I plan to further my education, I am forced to make the same decision that I was faced with almost three years ago: Do I stay in Philadelphia, or do I finally take the leap of faith and face the world alone for the first time? Like many facets of my situation, the choice is complicated. However, this time around, I know one thing I hadn’t realized before—whatever decision I make will be the right one.

Throughout my musings on the topic, I know that I’ve been too hard on myself sometimes. I’m still too hard on myself. But I know that whatever I decide to do, I’ll be a better person because of it. No question this time.

I know that many people reading this won’t understand my problem, and that’s okay. College comes with its unique challenges for everyone, challenges that make sense to no one else but themselves. But facing these challenges head–on—whether that’s in your South Philly bedroom or beyond—is enough. That’s what really matters, after all. k

34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 6

WORD ON THE STREET

“i’m literally in my pennywise era”

Hometown

Coppell, Texas

Major

Bioengineering with a minor in Asian American Studies

Activities

The Signal, Asian Pacific American Leadership Initiative, Penn Reading Initiative, TA of Bioengineering Lab Sequence

Friend, mentor, and part–time food enthusiast, Jerry Gao (E ‘23) dove headfirst into the Penn community the first day he set foot on campus. He radiates pure joy while discussing his work as a bioengineering TA, revealing his passion for both teaching and learning. Though most Penn students seem to have a myriad of activities padding their resumes, Jerry leaves a lasting impact on every community he’s immersed himself in at Penn. Whether in the bioengineering lab, teaching young kids how to read, or cheffing it up for his hometown friends, Jerry sprinkles love into all of his endeavors.

Jerry Gao

Between cooking, teaching, and volunteering, this senior brings authenticity and joy to every corner on campus.

BY NATALIA CASTILLO

Can you tell me a little bit about what brought you to Penn?

That’s a great question. My sister, who’s five years older than me, came to Penn, and I remember visiting her during my junior year of high school. I landed and Uber–ed

all the way in and thought, “Where the heck am I?” She said, “It’s fine, tell the person at the front gate that you’re here. They already know everything.” I remember opening the door and there were 20 to 30 people in her room—all just screaming surprise for me. I

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

remember thinking, “Who the hell are all of you?”

I was so surprised and shocked that they were here to celebrate, not even their friend, but their friend’s sibling. I think that moment showed me how at Penn people really

CAMPUS

Photo by Nathaniel Babbitts

care about each other. People really care to make relationships and make friendships; I found the balance super unique. That day in March of my junior year was the moment where I was like, this seems like a place that I can call home.

Now that you’re on your way to graduating, what have been your favorite classes or experiences in bioengineering or Asian American Studies?

In terms of bioengineering, there’s definitely a clear favorite that I have. It’s actually the class I’m a TA for right now. It’s “Bioengineering Modeling, Analysis, and Design,” and it’s basically the lab that all junior bioengineers take. There’s one particular lab we do in the class that always catches everyone’s attention; It’s called the cockroach lab. I think it’s one of the biggest reasons why people want to study bioengineering at Penn in particular.

It’s a segue into prosthetics and different medical devices that can help restore people’s limb functions. We order hundreds of cockroaches and then we put them in a little bit of an ice bath to anesthetize. We amputate their legs, which will essentially serve as our prosthetics, and then implant metal electrodes into two different spots of the leg. Then, we go into our computer program and type different lines of code that can help replicate different signal waves to move the legs. If you submit a wave with a particular frequency and particular amplitude, it’ll cause a leg to move in one direction, and if you do a different combination of the amplitude and frequency, it’ll cause it to move in the other direction. The next task is to trace the end of the leg and try to choreograph the leg to spell the letters B and E for bioengineering. It’s so fun to be able to see what combination of leg movements in the servo motor can form the backbone of the B for example, what can form the three lines of the E. I would say that’s probably my favorite moment in the bioengineering department.

What’s your favorite class you’ve had in the Asian American Studies Program?

One of my favorite classes is on Asian American entrepreneurship, taught by Dr. Rupa Pillai. She’s a wonderful profes -

sor. The class explores the validity of the American dream with regard to the Asian American experience. We looked at Asian American businesses—their successes and failures in assimilating into the American economy. One of my favorite aspects of the class was that it was an ABCS course, and we were able to interview and partner with different restaurants and vendors in the Philly area. We also partnered with the Philadelphia Asian Chamber of Commerce. It was our job to bridge these different communities and connect with the Penn Procurement System Service here.

We embraced these three communities to try to increase the number of

Asian American suppliers that are used at Penn—whether it’s vending, catering for food service, purchasing furniture for classes, or using different IT services that are Asian American owned. That experience was really enlightening, because we presented to members of Penn Procurement Systems, the Asian Chamber of Commerce, and different business owners in the Philadelphia area, showing them our findings and building lasting partnerships. I think that was the first time I got to really engage directly with Asian American businesses and try to integrate them into what we have here on campus.

34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 8 EGO

Photo courtesy of Jerry Gao

Now that we’re discussing personal impacts, tell us about your interest in cooking and your food Instagram account @ gaos_chows.

@gaos_chows really started over quarantine when I was bored out of my mind. I hadn’t seen a lot of my friends, so I wanted an excuse to connect with my friends. I figured, “What better way than food?” It’s the ultimate uniter. Everyone loves food! Everyone loves to enjoy different treats and goodies. I ended up going to the grocery store, and I started with a basic chocolate chip cookie recipe. Then, as I was, baking, I said to myself, “This feels exactly like my Intro to Chemistry Lab.” From there it was pretty easy. It was just like doing science, and it was really, really fun.

I ended up packaging it all up and delivering it to all my friends. Funny enough, I’ve never actually tried any of my food, because I’ll take a picture of it and then I just give it to my friends right afterward. At this point, it’s become a tradition. Every single break I text each of my friends and ask, “Are you going to be home tonight?” Obviously out of context, my message sounds a little ominous, a little mysterious. But now my friends know what I mean almost every single time I send that text, and I just get an all–caps response: “YES.” Now I have a list of people I make food for every single break, and I’ve optimized the route to know exactly what time I’ll arrive at each place by leaving at a particular time. It’s really fun and I think one of the best things about cooking is that it’s always a new challenge.

I feel like I’m never making the same thing twice which makes it so exciting for me. Although I haven’t posted on the account in a while, and at this point, it feels like my comeback post has to be the perfect thing.

How do you juggle so many different interests while being such a present member of your clubs on campus?

I think Penn Face for me was really awful. My first semester, I thought that I had everything under control. I thought high school was a walk in the park, and I remember when I took CIS 110, at first I didn’t think it was too bad. I just didn’t go to class, and

I thought that I knew everything. Then I took the midterm and scored a good two standard deviations below every single exam in that class. That was a big hit to my confidence. A lot of my friends around me seemed to be doing incredibly well in their classes. I’ve managed to get past that stage by looking at myself holistically and I recognize that, sure, coding is not my forte. I will never be able to write a quality “for loop” for the rest of my life. But that’s okay, because there are so many other aspects of life that not only am I better at, but I definitely take more pride in doing.

For example, I really enjoy being able to foster relationships and have meaningful discussions with people. It doesn’t matter if I get a C or a D in a class; those grades will never invalidate the experiences I have outside of the classroom. I love being able to teach other people and even though you’ll never catch me being able to do any sort of object–oriented programming, I love being able to teach a second grader how to differentiate between different vowel sounds and teaching different linguistic patterns so that they can excel and read chapter books going into third and fourth grade. I’ve

learned to prioritize what I value and understand that I’m not going to be great at everything. I’m proud of myself for being good at what I am good at and continuing to pursue those passions.

It seems like you’ve got the meaning of life figured out! So, I’m curious, what’s next after Penn?

I took a gap semester and I’m submatriculating into the master’s program to get my master’s in bioengineering. So, those are my short–term plans. In terms of long–term plans, I have no clue which path is going to be correct for me. I’ve started to go more with the flow and accept that there’s no GPS to life that’s telling me to turn left in ten weeks or to take a U–turn in a year. At the end of the day, you have to keep going and see where things take you.

Eventually, I want to be some sort of educator. I want to come back to Penn Graduate School of Education and try to either get my master’s or Ph.D. in education. I love learning about the psychology of our brains and learning how to teach effectively. I think that is definitely my longer–term future where I certainly see myself being a professor or a teacher in different countries. ❋

Best place to eat in Philly? Huge fan of Zahav.

Best place to study?

I got really sick of it last semester, but I have to go with Tangen Hall.

Best break?

Summer. I think I always come out of summer break like a new person in almost always a good way.

Best Children’ Book. If You Give A Mouse A Cookie.

There are two types of people at Penn … The ones who are masters of Sink or Swim and the ones who prefer to go to bed by 10 p.m.

And you are?

Definitely the latter. I go to the first Sink or Swim of every semester, and I call it a success.

CAMPUS

Breaking the Fourth Wall: Pennfluencers Tell All

Four

undergrads devoted to living life online talk the risks and rewards of turning classes into capital “C” Content.

BY NATALIA CASTILLO

For a generation that would rather get run over by a SEPTA bus than be forced to go dark on social media, it’s no surprise that having any kind of online presence can naturally progress into a content creation hobby. Now, being an influencer is not only a hobby, but an occupation. Though creators seem to take all shapes and forms, student–influencers have thrived in their own corner of the internet for some time. In particular, student–influencers at Penn (Pennfluencers, if you will) have taken over our for–you pages, but what are the implications of curating a robust online presence?

At an institution like Penn that grooms its students to consciously nurture their professional brand, it’s curious that a digital footprint can be both an incredible asset and a student–influencer’s Achilles heel.

Most of us have been on the receiving end of the “digital footprint lecture” from our parents or teachers. But for those of you who haven’t, it’s pretty much every post, pic, tweet, and thread that makes up the entirety of your online persona. These cautionary warnings stick with us long after our

formative years, reminding us to be wary of how #real we’re being online. But content creators at Penn are flipping this narrative on its head and redefining what it means to be terminally online. Curating a social media platform and amassing followers seems to take on a new meaning for Penn students climbing the corpo rate ladder.

The typical college influencer’s origin story starts with the quintessential college decision reaction video. High school students love to document their experiences applying to college, some even compiling videos of themselves opening their decisions to share with the masses online. With screams of joy, tears of frustration, and sighs of relief, these videos—

34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 10 EGO

Photos: Nathaniel Babitts

found largely on TikTok and YouTube—are primed for instant success. You’d be hard–pressed to find one with fewer than 10,000 views.

So what happens when the camera shutters close and the screen fades to black?

For Diana Lim (E ‘25), content creation came naturally after the success of her college decision video, which has now accumulated over half a million views. As with many other students, Diana’s video was a gateway into the world of content creation. Buoyed by her early suc -

cess, she knew that she wanted to document her college experience once she arrived on Penn’s campus.

One viral video gave way to a dedicated viewership; now, Diana posts monthly on YouTube to her 10,500 subscribers. Many students take the opportunity to offer a raw insight into college, revealing the ins and outs of campus life. At Penn, the student culture is half “Effective Altruism Retreat“ and half “Four–Day St. Patty’s Bender,” and student influencers aren’t afraid to show both sides of it.

For some students, the prospect of capturing their college experience on film seems horrifying. Nevertheless, it’s captivating and fascinating to watch a Penn student’s life unfold on a screen and online. While the attention is certainly a

plus, Diana explains that she wants to “democratize information for incoming college students.” The idea of the college experience can be ambiguous, but considerations like housing and the Penn dining plan don’t have to be so uncertain. In sharing her own experiences and advice, Diana hopes that her channel reaches people in a tangible way.

Diana’s videos have certainly reached a wider audience than just her peers at Penn. Since growing her channel, she’s partnered with a range of sponsors from beauty brands to college counseling companies. During her summer internship at SoFi, she even shared short day–in–the–life videos. ”I remember talking with the [internship] recruiter and I mentioned that I had a YouTube channel,” says Diana. “He said that stood out about me because he saw it as a hustle and had a lot of respect for that.”

Roene Nasr (C ‘24) is another content creator at Penn and Diana’s big in Alpha Phi. Though the influencer community is small and spread out, some students have connected over their content creation.

Roene’s TikTok journey follows a path familiar to most children of the COVID–19 TikTok baby boom. She established her

MARCH 2023 11 CAMPUS

platform with lifestyle content during the early months of the pandemic and now, roughly three years later, social media has become a fixture in her life.

With a following of 17.5k on TikTok, it’s understandable why Roene is fearful of being vulnerable on the internet. She acknowledges the concrete ways that Penn student–influencers curate their online presence by sharing busy days filled with club meetings and classes while omitting more intimate and raw moments. “I’m guilty of picking a day when I have a lot of things going on. I’m not going to choose a day [to vlog] when I sleep until noon and just barely do any work,” she says.

Like Diana, Roene has lofty ambitions—she’s a neuroscience major on the pre–dental track. Despite the demanding coursework, she’s found a way to marry her academic interests with her content creation. She recalls a particularly proud moment in which Penn Medicine reached out to collaborate with her to promote the opening of their new building, the Pavilion.

Roene explains that a brand deal typically pays more than an internship or scholarship opportunity; there’s an ever–present temptation for influencers to re–route their career plans in favor of living their lives online, full–time. Aside from the sense of personal accomplishment that comes from forming brand partnerships, the compensation certainly sweetens the deal.

Although Roene is set on her academic career, the (ostensibly) easy money associated with the full–time influencer lifestyle is certainly alluring. “It’s crazy to see the opportunities that content creation brings and it’s definitely helpful with the student debt that comes with undergrad and dental school,” she says.

Of course, not every Penn–fluencer makes their elite Ivy League institution into their online brand.

Andy Jiang (W ‘25) has amassed an impressive 3.6 million followers on TikTok and 1.35 million subscribers on YouTube,

with over a billion views. With a simple bet from a friend—$20 for 1,000 followers in a week—and global pandemic afoot, Andy dove into TikTok headfirst.

Ironically, he was the most chronically offline of his friend group. “I don’t think I’ve ever put any stories, posts on Instagram, [or used] any sort of social media,” Andy says, “so [that] was also the reason he directed the bet towards me.” In spite of that, Andy managed to win the bet—and then some.

“Very early on I channeled my social media presence online into something positive for people to look forward to during COVID-19 quarantine because spirits were very low,” Andy adds. He started a series called the Daily Dose of Good News, which gathered all the certifiably life–affirming news he could find and compiled it into a 32–second video every single day.

Now with over a billion views and nearly five million followers across his platforms, Andy has never considered deviating from his signature brand of feel–good storytelling. Despite his seemingly overnight success, he wasn’t deterred from the traditional college experience either—Andy has bigger upcoming plans in store. With the platform he’s building, he hopes to eventually start his own media company.

In the future, Andy wants to scale his platform bigger. Currently, he’s responsible for sourcing, writing, and recording his storytelling content. Eventually, he hopes to globalize his platform by outsourcing the majority of this work to people on the ground searching for the most captivating stories to tell. “I’m thinking about this hierarchy where a lot of different people are on the ground [in] various countries, various unique places.” Then he would take it upon himself to travel to meet these real people and tell their stories first–hand. This multi–tiered scheme would allow for content to be produced faster while “maintaining quality and the actual original goal and brand,” according to Andy. Whether it’s delusions of gran -

34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 12 EGO

“Through a pre–professional lens, content creation gives you a step forward because you understand modern marketing tools and you understand social media on a different level because you are someone who’s trying to create your own content too.”

— YASH MAHAJAN (C’25)

deur or genuine grit, it doesn’t seem like anything will be getting in Andy’s way.

For most student content creators, even those with Andy’s following, the brunt of the behind–the–scenes work is done alone. Andy does all of the basic research, script writing, filming, and basic cuts for edits. Only then does he pass along the product to be polished by another editor.

Andy’s roommate and fellow content creator Yash Mahajan (C ‘25)—together, they call themselves the “UPenn Hype House”—bemuses that he often hears Andy recording content late at night through their paper–thin shared wall. This conundrum was a point of contention for the duo earlier in the year. Yash recalls saying, “Andy, I want to sleep before 2 a.m. I can’t [when I] hear you saying ‘Did you know?’”

Although many student–influencers have found their influencer status to be both a creative outlet and a lucrative side hustle, that’s not true across the board. Yash originally made a TikTok on Ivy Day, recording his reactions to college decisions, and like most others, it went viral. Now he has a following of over 15k and uses his platform to create humorous, relatable content while sharing his Penn

experience. However, as an international student from Singapore, he faces monetization obstacles, ultimately preventing him from profiting from any of his content.

“There’s a TikTok Creator Fund, but I don’t qualify for it because I’m not an American citizen, so I’m not getting any money for any of my videos,” Yash says. He laments receiving exciting offers for paid Brand Ambassador deals that he can’t legally accept. Handshake reached out to him to be a panelist and create content for their new international student recruiting program, but the contract required a special international visa.

“I really wanted to do [the deal], so I sent it to the international student support office at Penn and I was told that if I accepted the contract I wouldn’t be able to sign on for an internship in the U.S. next summer,” says Yash.

Despite facing monetization challenges, Yash believes that social media is a powerful tool, and both the soft and technical skills he’s gained as a result will continue to parlay into his future career endeavors. He concedes that “through a pre–professional lens, content creation gives you a step forward because you understand modern marketing tools and you understand social media on a different level because you are someone who’s trying to create your own content too.”

In a sea of serious, well–accomplished Penn faces, it’s refreshing to see students document their college experience candidly. Some argue that to be an influencer is to perpetually curate your online presence, and indeed, the content creation process lends itself to editing a more exciting, digestible, and in some cases, viral version of yourself. But students like Diana, Roene, Andy, and Yash have found space to create content that doesn’t erase the person behind the camera.

Content creators themselves aren’t the only ones realizing and harnessing the power of social media. At Penn, the Signal Society has built a publication and community that encourages “the explora -

tion of unconventional career paths and creative passions at Penn.” Now a budding collective of “creators, designers, writers, and everything in between,” the Signal Society has become a home for those who seek alternative creative outlets. Despite the robust platform Andy built on TikTok and YouTube, he too found a community in Signal Society.

Past Co–Director of Signal Society Jerry Gao (E ‘23) explains that they use social media and content creation to shape a new, raw narrative of the Penn experience, even including failure in college and beyond. They have spun off of Jubilee’s popular series “Where We Stand” to highlight the myriad of experiences and perspectives of Penn students across all four colleges.

In another digital project, the Signal Society tackles “Penn face” through the “Anti–Resume Project.” Their aim is to foster dialogue around failure and overcoming challenges within your personal and professional career. “You think of a resume and you think of successes and highlights, but the anti-resume asks seniors, alumni, and faculty to fill in the resume with the ‘failures’ they’ve had during their academic and professional careers,” explains Jerry.

Penn’s pre–professional environment perpetuates an overwhelming pressure to both define your ten–year plan and ensure that it comes to fruition. In the midst of the scramble for success, student–influencers are finding new mediums and platforms to take charge of their own narratives, all while documenting their lives along the way.

These TikTok and YouTube videos have generated a wave of content created by, and for, Penn students. Sure, it’s up for debate whether or not a “Big–Little Weekend” vlog or a TikTok about Penn’s nightmare course selection period are really groundbreaking content. But all debates aside, we continue to consume these videos with a voracious appetite. So continue to like, subscribe, and comment— because who else is going to capture the Penn experience as earnestly as your local Whartonite or APhi sister? ❋

MARCH 2023 13 CAMPUS

“what is The Helen Gym”

This Star Physicist is Taking an Extraordinary Approach to Stargazing

Meet the Marshall Scholar and astrophysicist opening the door to disability inclusion in STEM.

BY SOPHIE BARKAN

BY SOPHIE BARKAN

is using a machine learning algorithm to look for metal–poor stars, typically the oldest stars in the galaxy, to gain insights into the earliest stages of the Milky Way's formation.

Yet despite her groundbreaking work, Sarah is keenly aware of the barriers that exist in science as a blind woman. She notes, “Generally, we visualize astronomy data. We make it a plot or a graph or an image. And that’s not super accessible.” Shortly after her first year at Penn, Sarah was introduced to Astronify, an initiative that specializes in sonification: transforming types of astronomical data into sound with the purpose of making it accessible to blind people. “That really—pardon the pun—opened my eyes to this broader world of disability advocacy within science,” she says.

her sophomore year. “It was quite scary to decide to get a guide dog,” she says. “It was frightening to change something from the way I'd always done it [and] to trust an animal to guide me around rather than a cane, where you are really relying on your own senses.”

As she sits beside her guide dog Elana, Sarah reflects that she leads her life through faith in others. “I'm trusting that people aren't going to try to interfere with my guide dog. As a small blind woman, I'm trusting that people aren't going to behave badly towards me. I'm trusting that if I stopped someone on Locust Walk and asked for di-

Sarah Kane (C '23) sheepishly admits that she entered the world of science because of the cult classic series Star Trek . In particular, as a young kid, Sarah felt most deeply connected to Star Trek ’s blind engineer. “It was the first time I had seen a blind person represented in science like that,” she says. Born legally blind, Sarah continues to defy barriers to pursue her passions in physics and astronomy.

Sarah began her research at Penn with Professor Bhuvnesh Jain in the galactic archaeology field, which focuses on the structure and formation history of the Milky Way. For her senior thesis, Sarah

For over two years, Sarah has worked as an accessibility tester for Astronify and is passionate about the intersection of science and disability advocacy. “There’s value in advocating for the inclusion of disabled people in science,” she says. Sarah has also worked to lead initiatives in order to connect visually impaired individuals with opportunities to pursue science on campus, including coordinating a trip for students from the Overbrook School for the Blind to Penn’s Department of Physics and Astronomy.

While Sarah diligently works to reach scientific breakthroughs, she is not afraid to face challenges in her own life. Sarah, who has used a cane her entire life, claims that one of her bravest feats was choosing to get a guide dog from The Seeing Eye before

34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 14 EGO

rections, they'd stop and give me a hand,” she says. “Sometimes that trust is met with disappointment, but oftentimes it's not.”

As Sarah heads off to earn a Ph.D. in astrophysics at the University of Cambridge next fall as a Marshall Scholar, she can’t help but ruminate on her beginnings.

“I got interested in science because of a fictional character on the fictional show Star Trek . It was great, but it wasn't real," she says. “I didn't know that other blind people in astronomy existed, and didn't know that anyone would care about making it so that we could be here.”

Sarah strives to be a role model and advocate for others, promoting resources for more disabled people to get involved in science. “What is most enjoyable and rewarding for me is the idea that I am holding open the door for the person behind me. Hopefully, the next little blind girl who wants to study astronomy won't have her only role model be a character from a fictional show.” k

CAMPUS

Photos: Nathaniel Babitts

Pretty in Pink: Marie Laurencin was a 20th–century “It Girl”

Marie Laurencin, a queer, mixed–heritage artist featured at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, thrived in women–only worlds.

BY LUIZA LOUBACK

W“hy should I paint dead fish, onions, and beer glasses? Girls are much prettier,” said Marie Laurencin, the painter who wasn't satisfied by how reality pre-

sented itself. Instead, she was mesmerized by dreamlike versions of life. Laurencin, despite creating a unique style of her own, is yet another female artist who’s been left out of the popular canon.

When you think of Cubism, famous artists such as Picasso and Braque come to mind. In contrast, Laurencin was forgotten by the French art scene and by the movement in which she developed an unprecedented approach. She is often regarded for her romantic involvement with poet Guillaume Apollinaire, following a common fate of many women throughout history: being remembered for a relationship with a man. Apollinaire even nicknamed Laurencin as "Our Lady of Cubism." Despite this, Laurencin is widely seen as a muse as opposed to an artist, a passive figure in the 20th century's most relevant and unique art movements: Fauvism and Cubism.

Laurencin was a 20th–century “It Girl” in many aspects of her life: an uninhibited, unapologetic, and expressive woman who created and shaped artistic trends to her own perspective. For example, her design for the Ballet Russe Les Biches [The Does], with loose, corset–less dresses, decisively influenced 20th–century women's fashion, something usually attributed to male designers such as Paul Poiret.

In comparison to Picasso, Laurencin’s work contains less harshness and more awe and defiance. At the age of 25, the artist sold a painting to Gertrude Stein (1874–1946), an American collector and modern art enthusiast living in Paris. The painting Group of Artists (1908) depicts people Laurencin was acquainted

34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 16 ARTS

Marie Laurencin, Portrait of Mademoiselle Chanel, 1923, Musée de l'Orangerie, Paris

with: Apollinaire (in the center of the painting); Fernande Olivier and Picasso (represented in the corners). Laurencin's pictorial strategy in this painting is the arranging of her subjects on her canvas in her own space. She relegated Picasso to the lower left corner, contrasting the rigidity of his contours with his profile face. Although Apollinaire is seated center stage, Laurencin reverses the gender convention of the family patriarchal portrait; she reclaims protagonism as the leader of the group. With this painting, Laurencin positioned herself not only in relation to her male colleagues—who evidently had an easier time establishing themselves as artists—but presented a broader political subtext.

At the Philadelphia Museum of Art, visitors can see eight of Laurencin’s works, including two of her most famous paintings: Nymph and Hind and Leda and the Swan . In her paintings, the viewer enters a Pinterest–like world of young women floating above abstract backgrounds, gray pigeons, and idyllic pastel–green landscapes. She searched for the “pretty” in the world, a pretty that embraced femininity rather than seeing it as a weakness.

Laurencin’s audiences received her sceneries as encouragement and hope for the people facing difficult times and grappling with questions of their own identity. These paintings, markedly feminine and

French, helped the country regain a sense of national unity post–World War I.

Laurencin’s personal life was as free as the scenarios in her paintings. She lived the majority of her life with Suzanne Moreau, defying society’s standards by adopting her as her daughter in order for them to share a life together. French law wouldn’t recognize same–sex civil unions until 1999. In fact, Laurencin envisioned a feminine utopia, celebrating women with poetry and prose and creating art that was subtle and subversive at the same time. Her queer modernist identity is visible in all of her art, from Lesbian Friends (1930) to Portrait of Mademoiselle Chanel (1923). She created a language of female creativity and lesbian desire, also leading the epicenter of queer expatriate women in Paris, cultivating friendships with other female lesbian artists, such as writer Natalie Clifford Barney and Gertrude Stein.

By centering all her paintings around

female figures, Laurencin explored them in new ways. Approaching sensuality, dedication, mystery, and fantasy, she pursued a tender and serious study of the soul of her models to capture their essence. However, curiously, French fashion designer Coco Chanel sent back her portrait for not recognizing herself in the painting. Marie painted Coco with black eyes, invisible eyebrows, and a hidden forehead.

Like our contemporary “It Girls,” Maurie Laurencin was confident in her artistic endeavors and continued channeling the defiant feminine spirit in her work, not letting male critique dictate her artistic technique. By the end of her life, Marie Laurencin produced about 2,000 paintings, more than 300 prints, book illustrations, scenery, and costumes. In terms of her works, Laurencin is still very modern: Her passion for female representation, fashion, and her ability to enter male–dominated spaces are common to many modern women today. k

MARCH 2023 17 CITY

Marie Laurencin, Group of Artists, 1908, Baltimore Museum of Art

A Reverberating Victory:

Shut Down Berks and the Fight for Immigrant Liberation

The Berks County Residential Center was officially emptied this month following nearly a decade of campaigning to shut down the immigration prison.

BY JEAN PAIK & AVALON HINCHMAN

Content warning: this text contains mentions of rape, sexual assault, and suicide, which may be triggering for some readers.

Residential center, correctional facility, processing center. Immigration and Customs Enforcement applies any num-

ber of these euphemisms to describe the places they use to incarcerate and deport immigrants. A locked facility that prevents immigrants from leaving the premises is,

34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 18 FOCUS

Photo Courtesy of Shut Down Berks Coalition

by definition, a prison.

In the United States, immigration policy authorizes the detention of “noncitizens to secure their presence for immigration proceedings or removal from the United States.” ICE claims the practice is “non–punitive,” but detainees are subject to trauma, isolation, and precarity for months and even years at these facilities—both during and beyond their time of incarceration.

Until recently, the Berks County Residential Center was one such immigration prison operating in Pennsylvania. For nearly a decade, immigrant leaders fought to expose the inhumanity and injustice of the BCRC, including its notorious history of abuse. On Dec. 1, 2022, immigrants and families formerly detained at the facility celebrated a historic victory. After years of local campaigning to close the detention center, ICE informed Berks officials that their contract with the county would be ending the following month. The community’s rallying call to “Shut Down Berks” had finally come to fruition.

The BCRC was originally one of three—but the only publicly owned—immigrant family detention centers in the United States, later transitioning to a women–only facility. The prison operated under a contract between ICE and Berks County, which owns the building and grounds of the facility and leased it to the federal agency. However, the conditions that led to the establishment of the BCRC and other immigrant prisons in Pennsylvania have been in the making for decades.

The issues with United States border enforcement stem from a legacy of federal policies designed to control and criminalize migration. Nuneh Grigoryan, assistant professor of communication and interim director for the Center on Immigration at Cabrini University, explains that an ongoing example is Title 42, a policy enacted under the Trump administration that limits the rights of people applying for refugee status and seeking asylum—particularly migrants from Haiti, Venezuela, and Mexico. “[Title 42] is a violation of a human … [and] internationally recognized right,” Grigoryan says, “that has caused panic and viola-

tions at the border where people are being either deported to [another] country or are detained.”

Policies like Title 42 have contributed to the growing number of detention centers and immigrant prisons across the country. In the fiscal year 2021, the federal government detained nearly 250,000 people across 200 facilities operated by ICE. According to Grigoryan, enforcement practices that seek to deport, detain, and forcefully separate migrants and families are “criminalizing something that is not criminal” and “justify the violence and suffering of the people.”

The Shut Down Berks Coalition—a group of organizations and individuals advocating for the closure of the BCRC—began campaigning in early 2015 after an employee raped a 19–year–old mother who was imprisoned at the facility. He was convicted of “institutional sexual assault” after other women in the facility came forward as witnesses and was sentenced to four months in prison, less time than the victim had been detained at Berks. “This really rattled the community,” says Adrianna Torres–García, deputy director of Free Migration Project and member of the Coalition. “People came together from different organizations … wanting to shut this center down because they saw all the violence that was being committed in that place.”

Immigrants in facilities like the BCRC are particularly isolated from community support and legal representation, increasing the chances of unlawful deportation and experiencing violence. Since 2001—when the detention center opened—there have been multiple documented cases of abuse, including malnutrition, inadequate access to health care, and treatment leading to suicidality and diagnosed PTSD among young children. In addition, guards performed flashlight checks every ten to 15 minutes at night, which is considered a form of torture due to sleep deprivation and the hindrance of proper REM cycles. Advocacy groups and community leaders exposed these harms as part of a larger effort to close the BCRC and abolish immigrant prisons.

Over the years, the Coalition has grown in size and strength, which “happened pretty organically,” says Tonya Wenger, who is a leader of

Shut Down Berks Interfaith Witness, a subset of the larger coalition. Embracing civil disobedience as a tool for change, Shut Down Berks “basically tried everything,” she explains, refusing to yield to a series of setbacks and disappointments. Through organizing efforts, the Coalition sought to make their demands known to the local, state, and even federal government. It was a “commitment to being as annoying as possible to whichever decision–maker we thought might tip the scales in our favor,” says Andy Kang, the executive director of the Pennsylvania Immigration and Citizenship Coalition, another affiliated organization.

At the state level, Shut Down Berks put pressure on the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, leading to a decision in February of 2016 not to renew the detention center license. However, Berks County appealed the cancelation in a legal case that dragged on until 2021, during which the prison remained operational. Over the course of this period, the Coalition repeatedly called upon then–Gov. Tom Wolf to address the illegal incarceration of families according to Pennsylvania state law.

In February of 2021, all families held at the BCRC were suddenly released, and the building remained empty until January of the next year. Under President Joe Biden’s administration, the prison reopened as an adult immigrant, women–only facility with double the number of beds, effectively expanding the presence of ICE detention in Pennsylvania.

That’s when the Coalition brought their fight to the White House. “In the last year [the Shut Down Berks Coalition] was trying to raise as much pressure on the federal level as possible, specifically around President Biden and Homeland Security,” says Kang. They urged Biden to immediately release everyone imprisoned at the BCRC and end the ICE contract in Berks County.

Shut Down Berks also coordinated various rallies—such as an event in Washington D.C. that drew a crowd even in sweltering weather—and formed partnerships with local colleges, schools, and churches. In addition, Kang explains that “whenever the president was in Pennsylvania, we would try to steal some of the media attention and at least insert the fact that immigrant detention is happen-

MARCH 2023 19

CITY

ing in Pennsylvania into the narrative.”

Throughout the campaign, the Coalition deliberately highlighted the voices of immigrants detained at the BCRC. “We took their lead [because] they knew what they needed,” Wenger says. This approach was vital considering “immigrants who are being detained or deported don’t have a platform to speak about the violations and tell their stories,” Grigoryan explains. Shut Down Berks listened to the detainees, and mobilized to amplify their message.

Ultimately, the Coalition’s diverse strategy proved successful, when it was announced in November of last year that the contract between ICE and Berks County would be officially terminated on Jan. 31. According to ICE officials, the closure was initiated because the BCRC became “operationally unnecessary” and “inefficient.” Adriana Zambrano, the programs coordinator at Aldea—The People’s Justice Center, says she thinks “it’s because they wanted to build a deportation mill at Berks and we frustrated that purpose.” By Jan. 10, the last woman left the facility. Everyone previously incarcerated was released rather than transferred, thanks in part to the continued activism of Shut Down Berks.

Aldea—a nonprofit organization that provides pro bono legal and social services to immigrant populations in Pennsylvania—was established in response to a lack of legal resources at the BCRC. The organization’s founders, Bridget Cambria and Jackie Kline, began receiving calls in 2014 requesting help for people in the facility without legal representation and decided to take action.

To meet this need, Aldea adopted a practice of providing universal legal services to anyone incarcerated at the prison, but not without obstacles. “It is extremely difficult to provide representation to someone in detention, [especially] when it comes to technical things like evidence gathering, declaration drafting, and accommodating a visiting schedule,” Zambrano explains.

It’s also challenging for many detainees to get a hold of the necessary materials for their case. “If you want to acquire other materials for yourself, you have to pay an exorbitant amount above what a person in the community would pay,” says Alyssa Kane, the managing attorney at Aldea. “It’s really difficult for [incarcerated

individuals] to even establish the basics of their own claims … especially for families who are also trying to take care of their own children at the same time.” There are financial barriers to legal representation as well. Detainees often can’t afford to pay for the lengthy phone calls necessary to discuss a complex immigration case with an attorney.

Jasmine Rivera, a coordinator in the Coalition, emphasizes that the goal was always to close the BCRC permanently—as the group’s name makes clear—and in the process, eliminate the resource gap that Aldea addresses. “It would have been easy for us to just focus on the

from staff employed at the prison. Additionally, Zambrano and Kane admit there are challenges posed by a partnership between abolitionist and universal representation strategies. That said, Zambrano believes that “in the Shut Down Berks Coalition we were able to merge those two worlds.” Shut Down Berks recognized not only the need for accessible legal representation, but also the importance of working to abolish the system of immigrant detention that originally imprisons and criminalizes these communities.

After eight years of multilateral campaigning, members of the Coalition believe persistence and consistency truly determined the outcome of their cause. “This is a pretty phenomenal group. They are incredibly committed and very resilient,” Kang says. Individuals formerly detained at the BCRC also played an instrumental role in the campaign, advocating for themselves and the freedom of others at the detention center through their leadership and willingness to share their stories.

Aldea’s Kane and other members of Shut Down Berks describe feeling an “overwhelming joy” when they learned about the closure—a testament to their efforts and the value of advocacy work. However, the immigrants formerly incarcerated at the BCRC remain the central focus, as the Coalition emphasized through a series of quotes in their recent press release announcing the victory:

conditions at the center … many organizations, that’s only what they do, but that just keeps the cycle going,” she says. It’s a difficult balancing act to both meet the immediate needs of imprisoned immigrants and address systemic issues of detainment and deportation, all with limited resources.

A hallmark of the Shut Down Berks campaign has been sensitively navigating opposing interests and integrating alternative modes of advocacy. On a local scale, the Coalition underscored that their pro–immigrant stance was intended to be in the community’s best interest, not an anti–worker plot to take jobs away

“‘For me it is a pleasure, the best news I have heard, happy to know that there will never again be families in Berks detention. No more depressed children locked up. Freedom is the most valuable thing that can be had, thanks to the support from everyone. Families should not arrive to be confined, no matter where they are from. I am more than happy that it will be closed down.’ — Lorena, mother incarcerated with her son for nearly 2 years”

“‘There were 28 days of uncertainty and anguish with my son, where we had a false freedom, rules for everything we did and we didn’t have the security of being able to talk to someone [while] inside Berks. We are happy that now they will have one less place to hold people and so [people] can move forward.’ — Mr. A, father incarcerated with son for 1 month”

In the aftermath of the shutdown, members of the Coalition will take much–needed time to “process and debrief” the events of the past several years, Rivera says. At the same time,

34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 20

FOCUS

This is a huge victory for everyone across the [United States] who is fighting to shut a prison down, because this really shows that when we keep pressure on our targets, and when we organize, we can have big victories.

ADRIANNA TORRES–GARCÍA

Torres–García recognizes that “when you’re organizing you have to think three steps ahead.” Residents of Berks County are already collaborating with the local government to transform the facility into something beneficial for the community, with proposed uses including a drug treatment or health and services center.

Two remaining ICE prisons in Pennsylvania, Clinton County Correctional Facility and Pike County Correctional Facility, and the Moshannon Valley Processing Center—privately owned and operated by the GEO Group—also necessitate future campaigns.

In particular, the Moshannon Valley facility poses a challenge to those speaking out against immigrant detention. The GEO Group “has a long track record of abuse,” says Kang, but private ownership of the prison means the company is profiting off of locking people up, and there is little accountability or obligation for transparency. Since no operating agreement exists between the Processing Center and the county, approaches employed by the Coalition in the Berks campaign lack the same efficacy. “I think the fight [at Moshannon Valley] is going

to be a lot harder … they’re not susceptible to that kind of pressure,” explains Torres–García. Even from a strictly logistical standpoint, the physically distant location of the prison makes it more difficult for local activists to get involved on the ground.

Still, the shutdown is not just a triumph for Berks County, but nationally as well. “This is a huge victory for everyone across the [United States] who is fighting to shut a prison down, because this really shows that when we keep pressure on our targets, and when we organize, we can have big victories,” Torres–García says. The Coalition teaches other advocacy groups that are uplifting immigrant voices and working to put a stop to inhumane detention practices that it’s not impossible to accomplish big changes.

The long–term goal for Coalition members and other human rights activists is the abolition of immigrant prisons. Systemic change is required to overturn current policies built on “structural racism, imperialism, colonial-

ism, and capitalism” that criminalize Black and brown immigrants—what Rivera calls the “deportation machine.” Grigoryan impels us to ask: “What are our values as a society and do we have empathy and compassion? Do we have a humane approach?”

As global concerns like climate change intensify, increasingly and disproportionately displacing communities as a result of environmental disasters, recognizing the fundamental human right to movement and migration becomes even more imperative. In this era “we have to make space for each other. We have to be willing to live together and take on those challenges together,” says Kang.

Arresting and incarcerating people exercising this right, building fences, and deporting immigrants back to dangerous situations is inhumane and unethical. The Coalition urges us to put pressure on those in power, demand change, and continue organizing in our communities, because, as Rivera puts it, “every single one of us deserves to be free, deserves our full dignity.” k

CITY Get more from your shopping. Weekly digital deals and special offers* Easy online shopping Meal planning inspiration Health services * Subject to program terms. Visit acmemarkets.com/foru-guest.html for full terms and conditions. Download the ACME markets app

It’s Just Hair

If you take everything else away, I would contend that my defining characteristic is my hair. As a kid, my nickname was broccoli, based solely on the fact my hair resembled a sprouting floret. Coming into the COVID–19 pandemic, I remember a teacher noting that while he struggled to recognize the rest of his students in their masks, he always knew I was approaching because of my signature mane.

22 34 TH STREET MAGAZINE

WORD ON THE

STREET

Illustration: Collin Wang

What would Nietzsche say about 2 a.m. bangs?

— BY NORAH RAMI

— BY NORAH RAMI

Everyone’s first compliment was of my curls and their last question was an inquiry into my hair routine—to which I always falsely answered, “I don’t even know,” as if I didn’t spend hours on Sunday pre–conditioning, co–washing, plumping, or whatever other tips I picked up from the endless curly hair influencers I followed.

Coming into college, I noticed the change in my hair before anything else. Sundays were filled with club meetings so there was no room for my time–honored ritual of wash day. Instead, I would haphazardly condition my hair at 2 a.m. when I could sneak a shower into my busy schedule. Exhausted from a long day of classes, I’d fall asleep before wrapping my hair in a T–shirt to protect it. The next day meant jumping out of bed minutes before class after a late night without enough time to carefully style my hair as I once did with pride. My hair became in essence an abandoned garden, once–pruned roses now wild and unkempt. It was yet another thing out of my control in a new world spinning faster than I could fathom.

If you ask me whether I believe in free will, my answer will depend on the time of day. Mornings, I’m an idealist. Around lunchtime, I start to converse with Nietzsche, and by night—having bounced through the day like a ping pong ball—I resign myself to believing I’m utterly powerless. The feeling was only exacerbated by the forward–thinking environment Penn fostered, where my future feels entirely unpredictable—as every acceptance or rejection was ultimately in someone else’s hands regardless of

how hard I worked. In a world where it felt like I had so little control over how people perceived me or what came next, I had once prided myself on taming at least my hair. Now, though, it had assumed a life of its own out of neglect—yet another variable uncontrolled.

Alone in my dorm after a Friday night out, I was once again pondering the merits of free will. There’s something about the hours between midnight and morning that feels forbidden, as if you’re trespassing on a world in which the rules of reality no longer apply. Anyone who’s had those moments at 2 a.m. alone, studying for a midterm or walking home from a party, remembers how the world was completely quiet and if you so desired you could scream into the abyss. Perhaps these are the pockets in which free will resides. That’s what I said as I grabbed my roommate’s scissors and headed towards the gender–neutral bathroom, bringing along my friend Bill who I ran into on the way. At 2:57 a.m., I had decided to endow myself with some semblance of free will, if only in determining the style of my hair. I pulled my locks over my eyes and cut them in one swift motion. Who cares what it looked like? Whether it was passable or the equivalent of a second grader with kitchen scissors, it was my own work, my own will.

Eventually, 2:57 a.m. turns into 9 a.m., and the rules of reality resume. You leave your dorm to brush your teeth, just as you have every morning of your life—and you will continue to do into oblivion. Until you run into your neighbor who looks at you and says, “Oh, so that’s where the hair in the bathroom came from.” k

MARCH 2023 23 YOUR BRAIN ON UPENN

Hustle Culture and The

Rise of Toxic Productivity at Penn

No, it’s not just getting shit done.

— BY OLIVIA REYNOLDS

24 34 TH STREET MAGAZINE STYLE

Graphic: Collin Wang

Penn’s student body has moved beyond the ‘80s–esque style of peer pressure that our parents warned us about. Rather than sneaking cigarettes in the bathroom between classes or cheating off your classmates’ papers, Path@ Penn’s “Request max course unit increase” form and PennClub’s mint green “Apply” button are the most alluring vices on campus.

At Penn, the pressure to always be “doing more” is palpable. A Sidechat post reading that a student “Never felt peer pressure to do drugs at Penn, but [they] constantly feel like [they] need to join 3 more research labs and take 8 credit units a sem” received nearly 500 upvotes and was the most popular post on the app that week, showing just how ingrained hustle culture has become in our lives.

Before even stepping foot on campus, Penn students accumulate a vast array of experiences employing their unique set of skills, passions, and interests. Classrooms are filled by business owners, nonprofit founders, tour guides, class presidents, and more. Being surrounded by so many motivated individuals is inspiring, but it can also be daunting. The line between admiration and comparison is thin—and easy to slip over.

Imposter syndrome runs rampant on campus, a disease students believe they can cure by enrolling in more activities than can fit on their resume. During recruiting season, it’s common to see peers applying to an average of ten clubs, even if they all require commitments of 5+ hours per week. Rather than choosing programs that excite them, students hunt for which clubs and classes will catch the eye of a future employer.

There’s a name for the resume bloating that occurs on campus—toxic productivity. In an article for RealSimple, licensed counselor Kruti Quazi defines toxic productivity as “when an individual has an unhealthy

obsession with being productive and constantly on the go,” adding that it “gives us a constant feeling that we’re just not doing enough.” While hustle culture has been on the rise across America, Penn serves as an intense microcosm of this problem.

Yash Rajpal (C, E ‘26), studying biophysics and bioengineering in the VIPER Program, has been personally affected by the influence of this phenomenon at Penn. “I honestly feel that if I have leisure time, I’m not doing enough,” he says. “I regularly don’t get enough sleep, and even though I leave time to be social, often I feel like it is more beneficial to advancing my network than actually simply hanging out with my friend.”

Students here are determined to prove that they deserve a spot in the revered Ivy League. “Productivity culture at Penn is grind until you fall. I see students all the time working to their limits; the number of people falling asleep in the library is unmatched anywhere else,” Yash says.

Rachel Blackwell (C ‘24), a varsity swimmer studying political science on the pre–law track, comments on the influence of business culture on productivity norms at Penn. “The toxic Wharton mindset contributes to this unhealthy lifestyle,” she says. “People always talk about selling out to consulting, or investment banking, or wealth management. I don’t even know exactly what those positions do, but I do know it entails an unhealthy lifestyle.”

The frenzy to find jobs in these fields is a constant stressor. Undergraduates covet these careers, regardless of major or academic background, citing the paycheck as worth the 60–hour work week. Students seem to be preparing themselves to be stretched to the brim, starting with the view that moments of rest, recuperation, and leisure could be better spent engaging in activities that produce tangible results.

Penn students’ overloading their schedules with activities they only find moderately enjoyable has negative mental health effects within the student body. In 2019, the World Health Organization expanded its International Classification of Diseases to include “workplace burnout,” showing that toxic productivity has detrimental

mental and physical health effects. Corroborating this standpoint, Penn was ranked as the institution with the most depressed student body in both American News Report and Humans of University.

The National Health Service ranks “enjoying yourself” as number two on its list of suggestions to be happier—which is exactly what Penn students should do more of. As an upperclassman, Rachel has removed herself from most of the Penn pressures surrounding resume building. “I try to fill my free time with activities that nourish my soul and help people,” said Rachel. “I’ve never felt the urge to compare myself to people at Penn because I know that everyone’s life is different and everyone’s career aspirations are different.” She followed by saying that “the fact that someone would participate in something just because they would put it on their resume is comical to me.”

The idea that you should only participate in activities you truly enjoy should be more prominent on campus. There needs to be a distinct shift within Penn culture, starting simply with our own attitudes. It should no longer be glamorized to take six or seven course units per semester or apply to a million clubs. The easiest way to go about this is just making a conscious change in the way we speak to our friends everyday. Instead of feeding solely into each other’s ambition, feed into each other’s passions.

Rachel shared one of her favorite non–academic pastimes. “I cook every single meal after classes; that really helps me de–stress. That’s my ‘me time’, where I can really think and meditate about how I’m doing,” Rachel said.

There are endless ways to break free from toxic productivity on campus. Go on a walk down Locust with music and an iced latte. Take SEPTA and explore Center City. Eat dinner at a nice restaurant. We speak of being trapped in the Penn bubble, but we all have the power to escape it. Write in a journal, watch your favorite show, or just literally just lay on your bed and stare at the wall. The mental benefits of pursuing hobbies or passion projects are often overlooked. A change starts with us—let’s take the necessary steps. k

YOUR BRAIN ON UPENN MARCH 2023 25

How do

34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 26 DATA

Netflix&Stress whenfeeling or binge-watch stressed depressed 72% ofrespondents 87% of respondents ’ fa spottocryin DORM/AP From retail therapy to altering appearances, delve into how Penn students manage feelings of stress and depression 34th Street surveyed 116 students on Feb. 16 What are some purchases you’ve made while stressed? Retail Relief 2.1.NewGirlGilmoreGirls 3.ModernFamily FanFavorites 116respondents’topshowsto watchwhenstressed UnravelingAround: Vintage Fendi bag for $500 after a boy made me upset.” “ I bought a projector and a jockstrap.” “ I bought Moon Boots while studying for finals. It hasn’t snowed since I got them.” “ 35%of respondents indulge in RETAIL THERAPY A lot of money has been dropped at Stump Philly for new plants.” “ (or don’t) BY SOPHIA LIU you

cope?

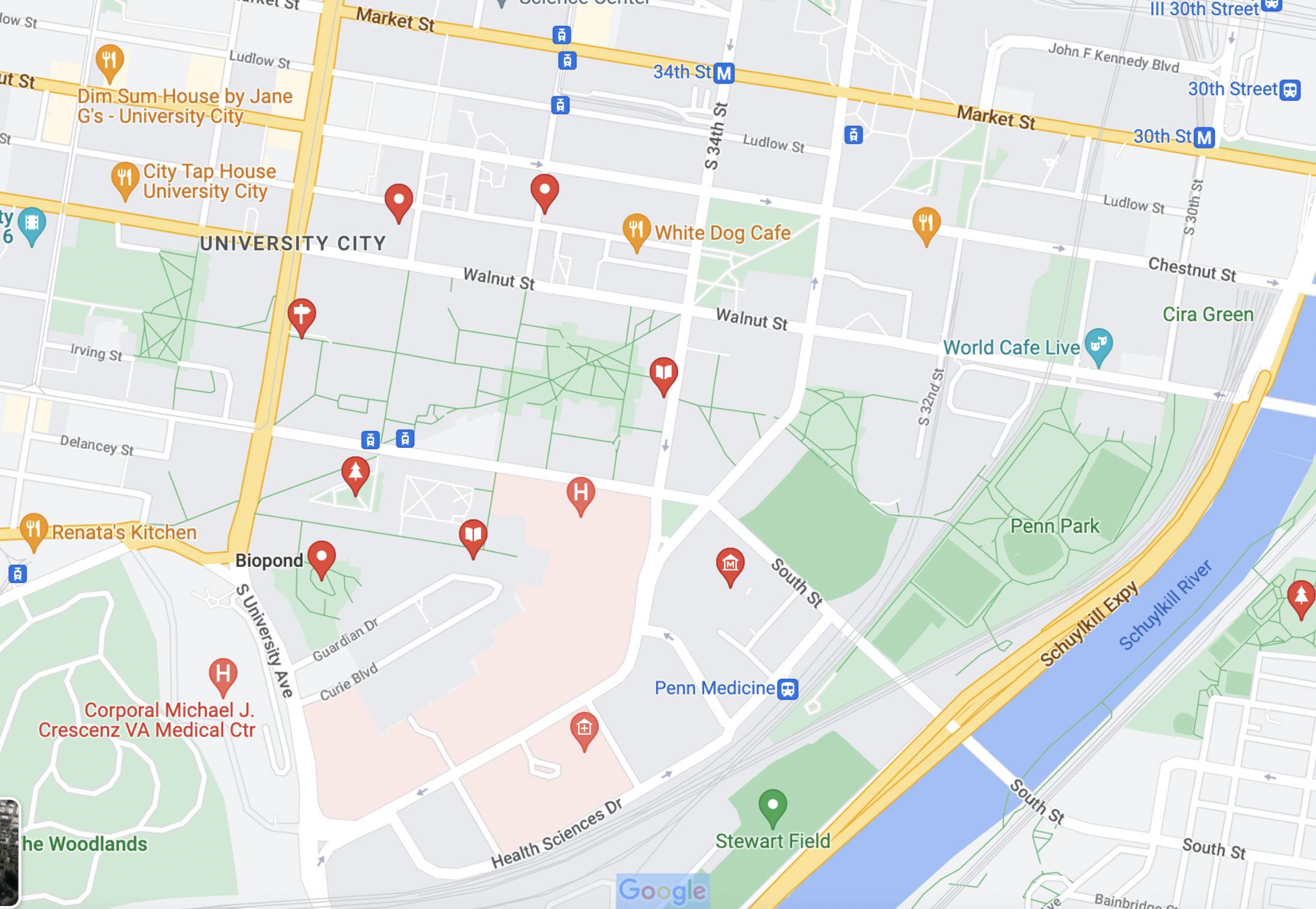

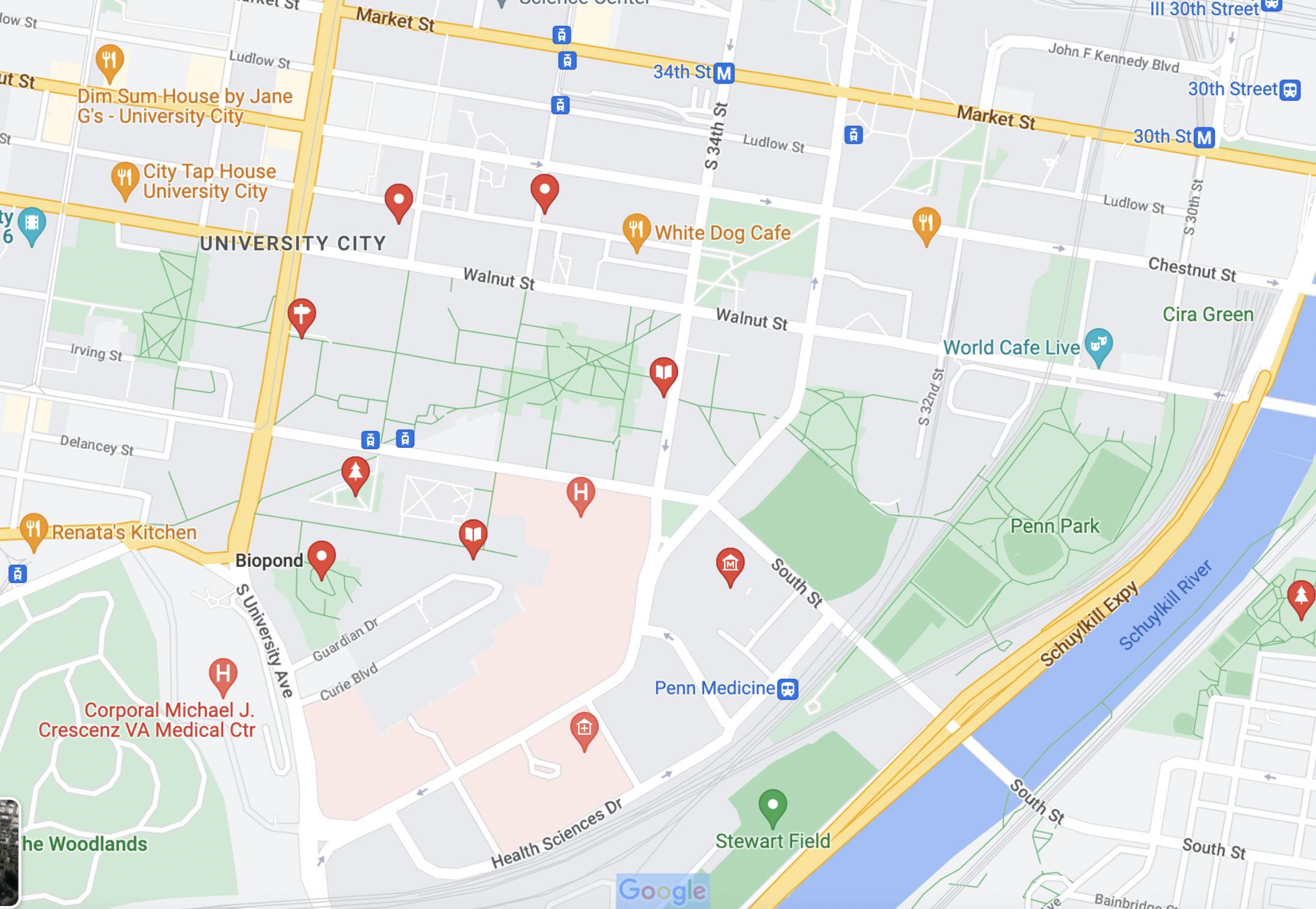

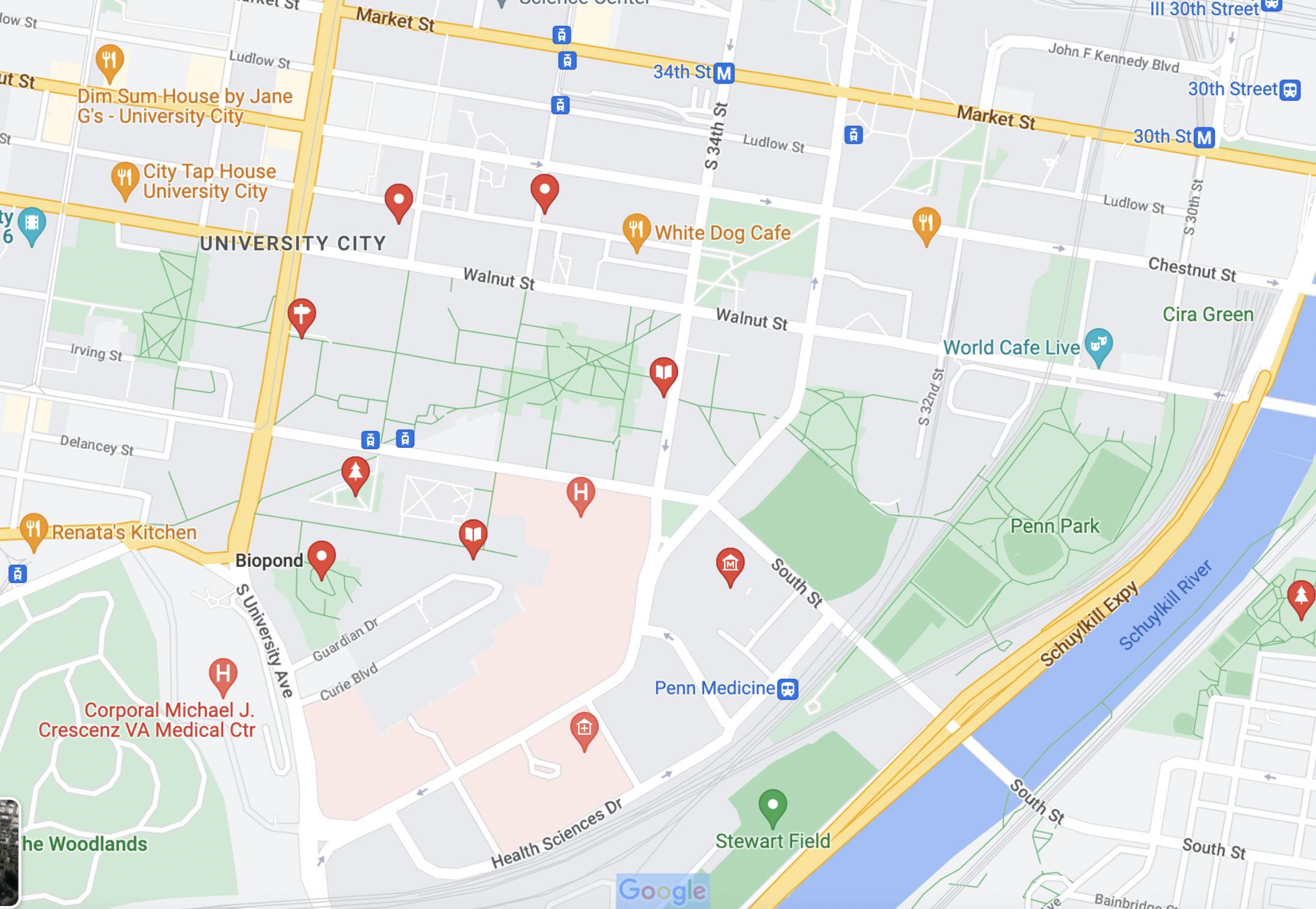

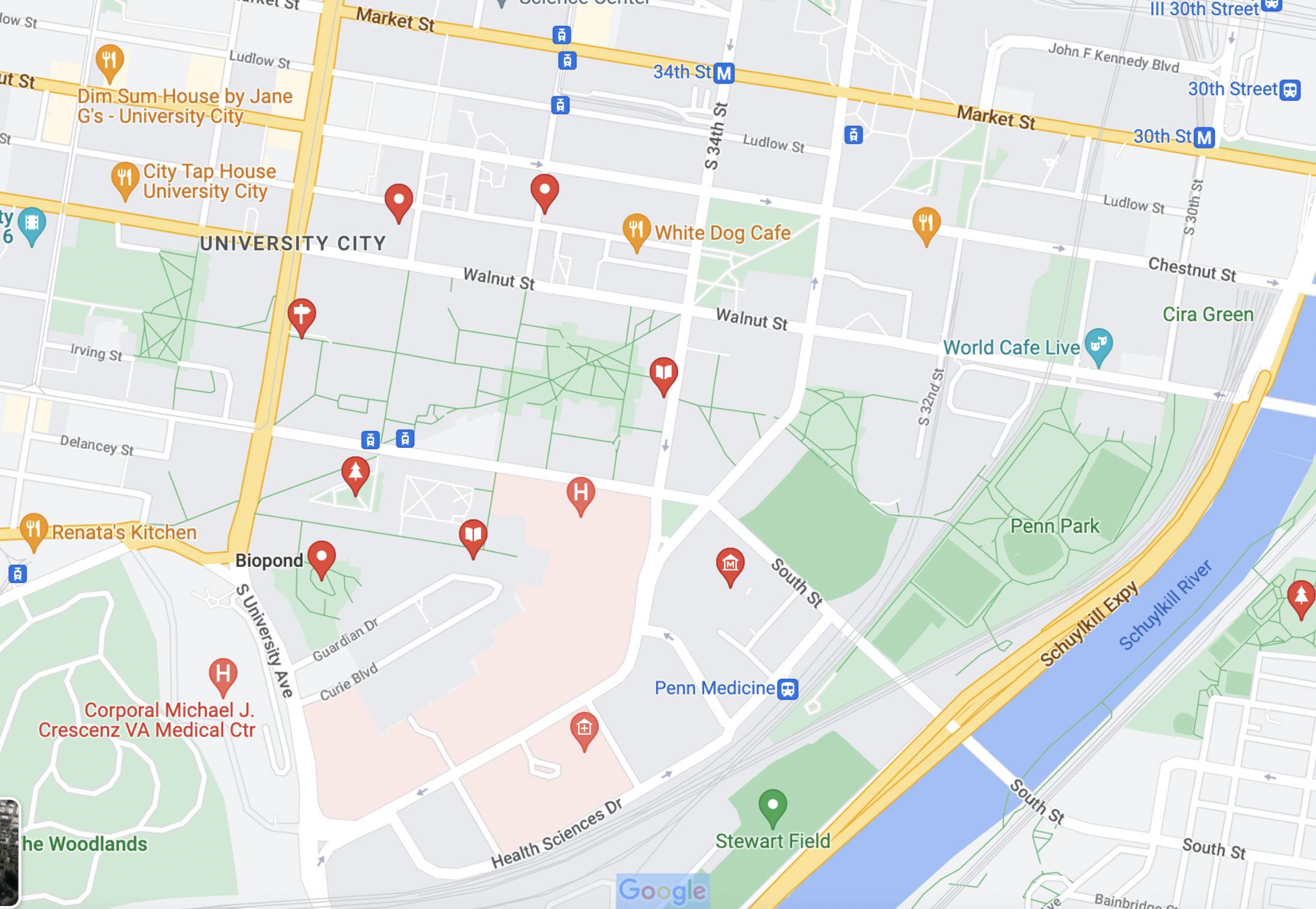

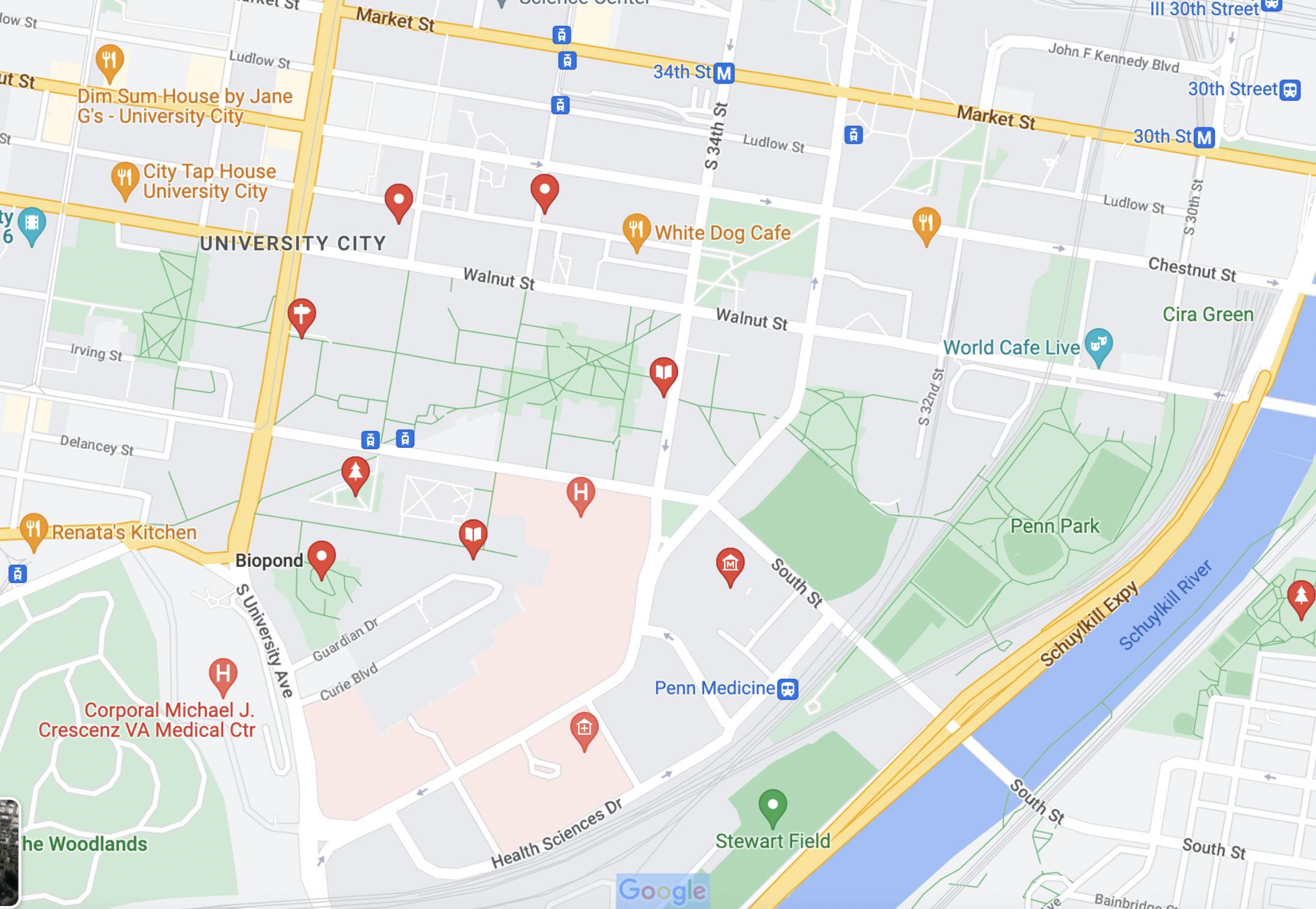

YOUR BRAIN ON UPENN Biopond SPRUCE ST. SOUTH ST. Quadrangle Pottruck Fitness Center MARKET ST. CHESTNUT ST. Penn Museum 36TH ST. 34TH ST. 33RD ST. Kings Court English House Fisher Fine Arts Library Lauder College House Biotech Commons favorite inistheir APARTMENT Explore some hairy stories about coloring and cutting Penn students’ greatest sources of stress Snip It Away Pressure Cooker Emily Kim First Year My ex-boyfriend broke my heart and I chopped half my hair off.” “ Noah Goldfischer | Sophomore I changed my major and got a mullet because I was stressed.” “ Karen Carvajal | Sophomore I [dyed] my hair pinkish red. It was to relieve some stress.” “ Mirage Rooftop Lounge Outside Bench Locust Emergency Exit Staircase Boardwalk Bathrooms Courtyard Library Cubicles HAMILTON WALK LOCUST WALK Pool SCHUYLKILL RIVER d:Pennstudents ’breakdowns,mapped 22%of respondents have impulsively ALTERED HAIR under stressful conditions Penn students’ top coping mechanisms 1. Eating (29/116 students) 2. Overworking (19) 3. Binge–watching (11) 4. Drinking (11) 5. Cleaning (9) 6. Retail Therapy (4) 7. Nicotine (4) 8. Weed (4)

to The Top 53% 17% 9% 7% Classes & Grades Career Prospects Social Life Existential Dread 14% Other (Family Life, Health,Self-Consciousness)Responsibilities, 9. Partying (4) 10. Sleep (4) 11. Altering Appearance (3) 12. Exercise (3) 13. Procrastinate (2) 14. Walks (2) 15. Other (5) WALNUT ST.

Coping

Popping the Bubble Positive Psychology

Positive psychology aims to help people reach their full potential. But can it really work for everyone?

Illustration: Erin Ma

FEATURE 28 34 TH STREET MAGAZINE

Bubble of Psychology

What makes life worth living?

What factors contribute to happiness?

What are the best paths to success? Positive psychology, the study of well–being, seeks to answer these questions and more. The field was popularized in the late 1990s by former President of the American Psychological Association and Penn’s very own Martin Seligman. Positive psychology emerged as a departure from traditional psychology’s focus on remedying “negative” emotions or behaviors. As Seligman asserted in a 2000 issue of the American Psychologist journal, “Psychology is not just a branch of medicine concerned with illness or health; it is much larger.” Instead of only helping individuals with mental illnesses, positive psychology is meant for everyone. In Seligman’s view, being mentally healthy is much more than simply not having a diagnosed mental illness. By studying positive traits—happiness, optimism, motivation, to name a few—Seligman hoped that his work could uncover why some people are more fulfilled with their lives, and use what they were doing differently to improve life satisfaction for the discontented.

The field has a large presence on Penn’s campus. Topics of study like happiness are particularly compelling at a University where rampant careerism causes students to prioritize material successes above all else. At Penn’s Positive Psychology Center, researchers study topics ranging from imagination to resiliency, with the aim of helping people “enhance their experiences of love, work, and play.”

In positive psychology, happiness can be quantified. Seligman even developed an equation that does exactly that: Happiness equals the sum of a person’s genetic capacity for happiness, their life circumstances, and the voluntary factors under their control. Positive psychology emphasizes that individuals can take action to ensure their happiness and well–being, and that agency is equally as important as our life circumstances. Actions one can take to improve happiness include strategies such as mindfulness, exercise, meditation, and staying away from negative self–talk. The field utilizes longitudinal studies (looking at the same group of people across a period of time), surveys, and case studies that are common in the social sciences, but also employs more neurological methods like brain imaging and hormone measurement.