O ering 60+ eateries, stores, and entertainment venues, Shop Penn has what you need to stay warm this season.

Winter calls for comfort food and cozy clothes, so get your cold weather cures at Shop Penn.

Wants Needs + Must-Haves

Shop Local. Shop Penn.

#SHOPPENN

@SHOPSATPENN

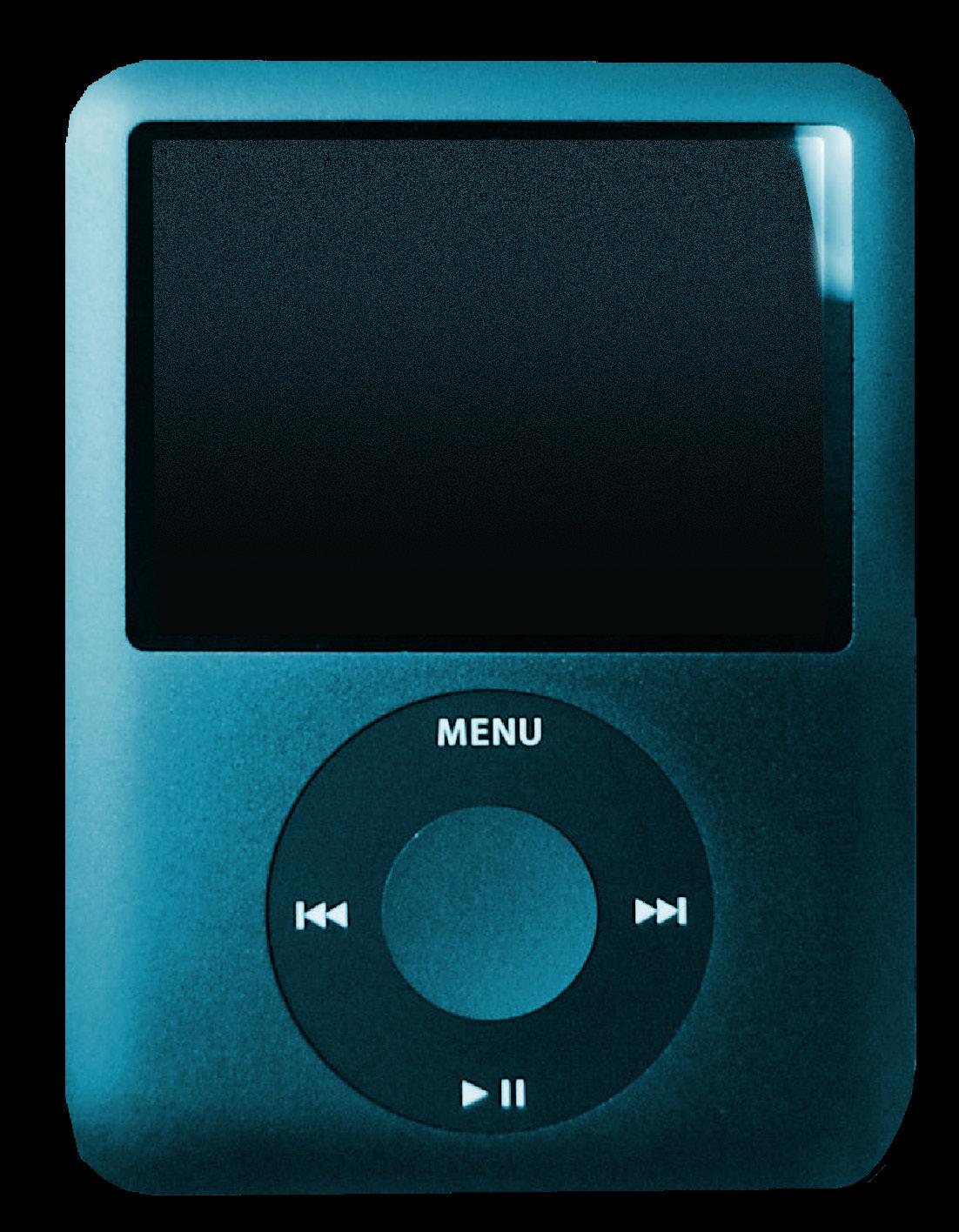

ON THE FRONT COVER

Fuck, marry, and kill, love is going through a rebirth.

However, no love is truer than mine for my co-Design Editor Makayla Wu.

By Insia Haque

5 1 4

8 First Place Essay: I am Never Getting Married

By Isaac Pollock

32 Loving by Numbers

Romantic vs. Platonic: Which love is more on our minds?

Ego of the Month: Teo Dragic

From Bloomers to Science Olympiad, this senior creates communities of care with creativity.

Philly's Labor Movement is Alive and Well

From the sports stadiums to the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, workers are demanding to be paid their worth.

40 Exploring Black Existence With Black Like That

An ambitious multimedia and multilocation art exhibition investigates with Black history in Philadelphia.

16

45 Crime, Culture, and Social Media as the Viral Fame Machine

Your 'problematic fav' is a real life criminal.

Rin the modern age ses

“Something old, something new.”

Veronica Mars Did Feminine Rage Before it was Cool

Celebrating 20 years of TV’s best not–so–bubbly blonde.

ON THE BACK COVER

What is love, if not a reason to get naked and make stupid mistakes?

I am nothing if not an amalgamation of all the people I have loved before.

Two households, both alike in dignity, In fair Philadelphia, we set our scene,

But this is no great Shakespearean romance. It seems that by the time you graduate from college, you should have at least three failed situationships you have to avoid eye contact with while walking down Lo cust, a homoerotic friendship that would’ve gotten you diagnosed with hysteria in the 1500s, and a hoard of embarrassing Hinge profile screenshots. Yes, love is a messy, messy thing in your 20s. As we venture into this strange jungle that is adulthood, there is an insurmountable pressure to not just find yourself, but also to find your soul mate. But when every moment is a potential meet–cute and everyone a potential suitor, life feels romantically exhausting.

After all, these frat bros cannot be the same boys Juliet laid in her deathbed over.

There is no denying that our society is ruled by romantic desire. It is the subject of great poets and the theme of way too many songs. But a life with only one partner is a life of missed opportunity. What is a renais sance if not a period of cultural change, an age of exploration? And what is love if not an expansive, all–encompassing force?

So let us move away from one–and–done romance. There is a breadth of love to discover beyond the realm of dating. What does it mean to love? Street is ask ing that very same question. It is my housemates who offer to cook me din ner after a bad day and my first–year hall friends who always make sure to walk me home, even if they now live on the opposite side of campus. It is my older siblings who answer phone calls at any hour of the night and my parents who still wish me luck before every exam and read every single article I write. It is the best friend I bring as a plus–

one to a wedding, the childhood friends that still remember my favorite movie all these years later, and all the darling people I have met through this very magazine.

For never was a story of less woe than this Street editor and her disinterest in Romeo.

SSSF,

EXECUTIVE BOARD

Norah Rami, Editor–in–Chief rami@34st.com

Jules Lingenfelter, Print Managing Editor

lingenfelter@34st.com

Walden Green, Editor–in–Chief green@34st.com

Hannah Sung, Digital Managing Editor sung@34st.com

Arielle Stanger, Print Managing Editor stanger@34st.com

Fiona Herzog, Assignments Editor herzog@34st.com

Alana Bess, Digital Managing Editor bess@34st.com

Insia Haque, Design Editor haque@34st.com

Collin Wang, Design Editor wangc@34st.com

EDITORS

EDITORS

Nishanth Bhargava, Deputy Assignments Editor

Avalon Hinchman, Features Editor

Bobby McCann, Features Editor

Jean Paik, Features Editor

Chloe Norman, Features Editor

Natalia Castillo, Assignments Editor

Sarah Leonard, Focus Editor

Kate Ratner, Assignments Editor

Kate Cho, Style Editor

Anna O'Neill–Dietel, Focus Editor

Anissa T. Ly, Ego Editor

Naima Small, Style Editor

Sophia Mirabal, Music Editor

Norah Rami, Ego Editor

Kas Bernays, Arts Editor

Hannah Sung, Music Editor

Jackson Zuercher, Film & TV Editor

Irma Kiss, Arts Editor

Makayla Wu, Design Editor

Weike Li, Film & TV Editor

Danielle Jason, Street Social Media Editor

Rachel Zhang, Multimedia Editor

Cassidy Whaley, Social Media Editor

Kayla Cotter, Social Media Editor

Jackson Ford, Street Photo Editor

Jean Park, Multimedia Editor

Weining Ding, Multimedia Editor

Julia Fischer, Copy Editor

Deputy Design Editors

Wei–An Jin, Ani Nguyen Le, Sophia Liu

Asha Chawla, Copy Editor

Design Associates

Garv Mehdiratta, Copy Editor

Deputy Design Editors

Insia Haque, Katrina Itona, Erin Ma, Janine Navalta

Kate Ahn, Dana Bahng, Annelise Do Design Associates

STAFF

Features Staff Writers

Asha Chawla, T Fong, Katrina Itona, Danielle Jason, Wei-an Jin, Erin Ma

Katie Bartlett, Delaney Parks, Sejal Sangani

Focus Beat Writers

STAFF

Features Writers

Leo Biehl, Dedeepya Guthikonda, Sara Heim, Sophia Rosser, Rahul Variar

Style Beat Writers

Layla Brooks, Emma Halper, Alexandra Kanan, Claire Kim, Felicitas Tananibe

Lily Howard, Anna O'Neill-Dietel, Caleb Crain, Charlie Jenner, Avalon Hinchman, Diemmy Dang, Eleanor Grauke, Samantha Hsiung

Music Beat Writers

Focus Beats

Kelly Cho, Halla Elkhwad, Ryanne Mills, Olivia Reynolds, Mehreen Syed

Sadie Daniel, Kayley Kang, Mariam Ali, Saanvi Agarwal

Arts Beat Writers

Style Beats

Jojo Buccini, Jessa Glassman, Eyana Lao

Film & TV Beat Writers

Caitlyn Iaccino, Kate Ahn, Priyanka Agarwal, Erin Li, Jack Lamey

Music Beats

Mollie Benn, Kayla Cotter, Emma Marks, Isaac Pollock, Catherine Sorrentino

Ego Beat Writers

Jett Bolker, Maren Cohen, William Cai, Amber Urena, Danielle Jason

Jo Kelly, Kyle Grgecic

Sophie Barkan, Noah Goldfischer, Ella Sohn, Vikki Xu

Arts Beats

Staff Writers

Richard Paget, Lynn Yi, Logan Yuhas, Katrina Itona, Maya Grunschlag, Alex Gomez

Film & TV Beats

Aden Berger, Sophia Leong, Bea Hammam

Morgan Crawford, Heaven Cross, Angele Diamacoune, Rayan Jawa, Enne Kim, Jules Lingenfelter, Luiza Louback, Dianna Trujillo Magdalena, Yeeun Yoo

Ego Beats

Audience Engagement Associates

Talia Shapiro, Christine Oh, Eva Lititskaia

Staff Writers

Annie Bingle, Ivanna Dudych, Yamila Frej, Lauren Pantzer, Felicitas Tananibe, Liv Yun

Isaac Pollock, Vivian Yao, Katie Bartlett, Derek Wong, Luiza Loubeck, Maddy Brunson

LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Andrew Lu, Kyunghwan Lim, Insia Haque, Gia Gupta

LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The Land on which the office of The Daily Pennsylvanian stands is a part of the homeland and territory of the Lenni-Lenape people. We affirm Indigenous sovereignty and will work to hold the DP and the University of Pennsylvania more accountable to the needs of Indigenous people.

The land on which the office of The Daily Pennsylvanian stands is a part of the homeland and territory of the Lenni-Lenape people. We affirm Indigenous sovereignty and will work to hold the DP and the University of Pennsylvania more accountable to the needs of Indigenous people.

CONTACTING 34 th STREET MAGAZINE

CONTACTING 34 th STREET MAGAZINE

If you have questions, comments, complaints or letters to the editor, email Walden Green, Editor–in–Chief, at green@34st.com You can also call us at (215) 422–4640.

If you have questions, comments, complaints or letters to the editor, email Norah Rami, Editor–in–Chief, at rami@34st.com You can also call us at (215) 422–4640.

www.34st.com © 2023 34th Street Magazine, The Daily Pennsylvanian, Inc. No part may be reproduced in whole or in part without the express, written consent of the editors. All rights reserved.

www.34st.com © 2025 34th Street Magazine, The Daily Pennsylvanian, Inc. No part may be reproduced in whole or in part without the express, written consent of the editors. All rights reserved. MR. PRESIDENT

Queens, N.Y.

Major

Health and societies

Activities

Science Olympiad at the University of Pennsylvania, Bloomers Comedy, Carriage Senior Society, Osiris Senior Society, Turner ESG Fellow, Fund for Health, Penn Health Equity Center

Teo Dragic (C ‘25) sits cross–legged on her bed, the walls surrounding us plastered with memories from her world. From mosaics of group photos, concert posters, playbills, a Fleabag script, and Bloomers promo, the art tells a vibrant story. Teo’s dedication to health, community, education, and performing arts leaves one to wonder how she balances everything. As we talk about the diverse communities she inhabits, she effortlessly shifts between topics, from urban outreach to artistic expression, reflecting the fluidity with which she navigates the world, all while making room for herself and others.

I know you are from New York, but could you tell us more about your background?

I feel very strongly connected to being from Queens. My parents immigrated here from Serbia, and we lived in a neighborhood surrounded by a lot of Eastern European immigrants. I think that that was very important to my upbringing. It made me feel very connected with my culture from a very young age.

I actually haven’t gone to Serbia since

From Bloomers to Science Olympiad, this senior creates communities of care with creativity.

BY ANISSA T. LY

2018, but we used to go every summer. My entire family lives in Serbia or Germany. I’m not German, but a lot of my family immigrated to Germany for work purposes. I have very good contact with my family in Serbia, but I haven’t gone back since my grandmother started flying in to visit us—instead of us flying to Serbia. I really, really want to go back post–grad and visit and see all my family. I was able to go to Germany this summer to see my grandfather, and then some people flew in from Serbia to also see me, my dad, my brother, which was awesome. I do feel very, very connected to being Serbian. That’s been a huge part of my upbringing.

What can you tell me about some of the communities you are involved in?

Whether it be extracurricular activities or my friends, I think that at its core, [everything is] all driven by community. [Community] is insanely important to me. I hope that my impact will have been to help other people have a good day or enjoy their Penn experience. Anything that I do, even coursework or my thesis, it’s all shaped by interactions I’ve had within the Philly community and the spaces that I’ve engaged with. For example, my thesis on safe injection sites: I grew up seeing a lot of drug overdoses, and I’ve worked with Fund for Health (the Environmental, Social and Governance Initiative with Wharton and Penn Medicine) and Prevention Point Philly with safe injection sites. And I can see the benefits they’ve had on the community. I’m very happy that I’m here. Being from a big city, I have always viewed Philly as such a tight–knit community. I feel like everything that I’ve done has been driven by the larger purpose of building community, being involved with my community, and learning about different communities that I’m in. I want to be remembered for having had an impact, forming community here, and engaging with the Philly community and my friends. Would you say that you are a planner, more spontaneous, or both?

I will say yes to anything and every -

thing, and then realize that shit’s not gonna align in my schedule. But I will still try to make it happen. Today, I’m going to the WizChord a capella show, and tomorrow, my roommates are running the marathon. So, to carb–load, they're having a pasta making party. After the WizChord show, I’m gonna run back here and make pasta and celebrate my roommates. Then I have friends’ birthdays later in the evening. It’s a lot of running back and forth. It might just be FOMO, but I love being around people, and I love being around my friends, and I love meeting new people, and for that reason, I will say yes to everything. I like to show up and be there for people, see my friends, be proud of them, and celebrate them. In a lot of ways, a lot of things that I say yes to, spontaneity–wise, are to be there for other people and be there with my friends. They’re insanely talented. Things will come up like that throughout my week, and I will just be like, “yeah, I want to be there, and I want to show up.”

What was your biggest adventure here at Penn?

Swalloween is the first thing that comes to my mind. I woke up at 7 a.m. that day and didn’t go back home until 7 a.m. the next morning. The day started with me running to Fishtown to go to Thunderbird Salvage to get more dolls for the house, because the theme of Swalloween this year was Dollhouse. Then I was setting everything up from 12 p.m. to 4 p.m. until we realized that we did not have enough props for the basement. So then me and my awesome friend, Laura—she’s our treasurer—ran into Center City, and we couldn’t find any Ubers back so we waited for a SEPTA, and then the SEPTA wasn’t coming, but as we were leaving, suddenly it came. We were able to get back to Herzog, where [Swalloween] was hosted, and then it was nonstop from that moment forward: figuring out the DJ, moving vans, driving around. I picked up giant animatronics two blocks down from Herzog, and I probably looked insane lugging around a giant skeleton

to set up at the entrance. Once it started, seeing everything unfold and seeing what my friends and I worked so hard to plan made me so proud. Just hearing that so many people had such a good time made me really happy. I know that it’s not the craziest adventure, but in my head, that day never ended. It seemed so long in retrospect. Searching for different things, trying to pull everything together, and finally succeeding made it a massive day. A lot of love went into it.

I joined Science Olympiad in my freshman year of high school. I loved it. It was where I met some of my best friends from high school, and when I came to Penn, I wanted to continue doing that. SOUP was my community in high school, and I wanted that similar community going forward. I’m very grateful for the people I met through SOUP.

SOUP is a competition for middle schoolers and high schoolers, and it’s run internationally. There are roughly 23 different events in different branches of science that you can compete in. I did a lot of the public–style events. Penn runs one of the largest invitationals in the country for high schoolers. We write the tests and plan the entire day, and in February, students from across the country come to compete.

Something that I’m particularly proud of is the fact that we’ve started working with Penn Medicine for an urban outreach program to help middle schoolers. I was president of the program last year with my good friend Aurora, and this year I’ve been doing urban outreach. We get grants from Penn to do science mentorship and start Science Olympiad programs in middle schools in Philly. We also just work to get more funding so that we can host Philly high schools who don’t have to pay an entrance fee at the Penn Invitational. A policy that my old co–President Aurora and I put in place was for there to be a minimum of slots reserved for Philadelphia high schools. I think it helps so many people gain ex -

perience and confidence. It helps high schoolers get more excited about science and STEM fields and even public health. We’ve gotten them to tour labs at Penn Med and the School of Engineering and Applied Science. There’s a lot that goes into SOUP, and I really like it because other invitationals don’t do urban outreach programs. I care a lot about education. My mom’s a public school teacher. I feel very strongly about having gone to public schools in New York. I learned a lot at Penn in my health and societies classes about how education and health are intertwined. Thus SOUP, going beyond just running the invitational, was probably the most fulfilling part for me.

Most meaningful experience here at Penn?

Bloomers, for sure. I, like a lot of people, came to Penn with a pre–professional mindset. I wanted to go to law school. I was very interested in public health— still am—but throughout high school and middle school, with friends at home, I would just like, record videos and make short films. They were awful, but I had this interest in film, production, and entertainment, which is part of the reason why I joined Bloomers.

It all started when I went to Bloomers and Mask and Wig’s free show in my freshman year, and there was just something that felt like it clicked. I could see myself in a group like that. I hadn’t experienced that feeling before in other organizations that I had been a part of, up until college. I know that my parents have my best interests at heart. They told me to do X, Y, Z and get a job, and they were part of the reason why I didn’t want to disappoint anyone by choosing a nonconventional route. But I auditioned for Bloomers, and I’ve been working on video and graphic design. We work very closely with the writing team to make promo material. I just have never had something completely alter what I want to do. I think that Bloomers was the most important community to me at Penn. It encouraged me to want to pursue enter -

tainment. I’m really interested in directing and film in general, and I think that without Bloomers I would not have been able to definitively say that. The people there are some of my best friends in the world. Being surrounded by such creative, awesome, funny people—I feel as though it is a second home for me. It’s the best decision I made here. I can’t emphasize enough how much I love it. I love Bloomers—hands down. If you look at the wall, these are all the Bloomers posters.

[“I'm sure I saw this one while waiting for the elevator.” I say, pointing at a poster on her wall.]

Well, it was probably me that put it up.

What has been your biggest takeaway, or a lesson that took time revealing itself for you while at Penn?

The people that you surround yourself with are the most important thing you get out of Penn. I don’t know what I would do without my friends. They are a key part of my life, and they have brought me so much joy. I get to learn from really cool people and see how talented and amazing they are in everything they do. I carry so much of that within me, and I’ve

really been shaped by everyone who’s in my life now. People are very important to me.

Last Sunday, I was supposed to work on 20 pages of my thesis due on Tuesday, and I hadn’t written anything. It was my really good friend’s birthday and instead of buying a cake, another friend and I baked him a carrot cake. I’m happy that my Sunday was spent doing something like that. Over these four years, I’ve learned to prioritize people. Academics are obviously important—we’re here to get a degree—but before, I’d never put friends as high up as I do now. I think that I’m so much better for it.

What is your next stop, and what do you envision for yourself in the future?

I want to be either in New York or Los Angeles working on film directing. I don’t know in what form, but I really love comedy. My roommate wants to do medical documentary work. She’s also an HSOC major, so that’s something that we’ve talked about extensively—working on projects together. I really want to pursue that. k

There are two types

And you are?

BY KATE AHN

Design by Kate Ahn

IMET ___ WHEN THE AIR smelled like water and the sun fell onto the pavement in fat, white–hot rounds in between old ginkgos. There was cigarette smoke and car exhaust in the air, a flower wrapped in plastic in my hand, and cicadas yelling to get laid. Humidity. My hair stuck to the back of my neck and his to his forehead as we waited for the train. He told me—jokingly—that one day he would try to win me over in the wintertime. “It’s when people are the loneliest,” he said. Easier to fall in love, he meant.

“I don’t really get lonely in the winter,” I replied.

“You’ll see,” he told me. “The air smells different.” That was summer.

It’s snowing outside, my first snow in six years. It’s too lean for January snow. Not the kind that sticks, fat and cold, onto ledges and roofs, the hair of a beautiful boy you met in the summertime. I think back to that summer

and think of how impermanent everything felt; the both of us, bumping into each other, as the two trains we were, hurtling in opposite directions—me abroad, him to stay— knowing we would turn away, rattling in our tracks and passing and curving away in balmy summer winds. Rattle, rattle.

Love changes; it does not stay. I know this. You are a name, then a face, then an introduction; then an I–thought–of–you–today and an I’ll–take–you–there–someday; and then back to a face, a name, an occasional like on my story. You become the boy who dumped me when I was 16 in true high school fashion—a much–too–green “I love you,” which I didn’t know how to respond to, and then

every shape and color. Love locks, the kind you go to fasten with your boyfriend, giggling, hoping that you’ll last forever. The walls are dripping with them. Caving in under their weight. I read yesterday there were at least 82 tons’ worth of locks in there, and I also read someone comes to remove them all every few years to stop the walls from falling apart. Then somebody else comes in with their boyfriend and does it all over again. I haven’t gone. I bet the locks talk to each other in the wind, giggling at our childish attempts at permanence. Rattle, rattle.

Winter again. I tell my friends I am writing an essay about love. “It’s about how love is impermanent,” I say. They give me a look. “So you think people can’t love somebody else forever?” I pause. Of course, I think there’s love that lasts. I just think it can’t stay the same forever, you see, because the way you loved somebody in high school cannot be the same as the way you love them at 72. The way you think you love somebody at 16 just because the boy you liked said it to you and you think you’re supposed to reciprocate isn’t the way you love now. “And that’s okay,” I say. Changing isn’t a bad thing.

and the walls are laden with locks of

Sometimes I think I can see it, the pieces that stay, staining your fingertips. Something like the ends of my hair staying a touch lighter than my roots because I bleached it three years ago, heartbroken, on a whim; something like eating dinner with old friends, lightheaded from soju and the thought that we are no longer seven years old and whacking at Wii controllers with sticky hands; something like someone else’s sweater that makes me a little guilty when I see it folded away back home. I wish it wasn’t in bits and pieces. I wish that what’s permanent isn’t what’s left behind.

If love is swept up in a perpetual renaissance, changing and dying and

reappearing again, I want and seethe and plot with all the petulance and grace of an only child, a love lock. Miss you. Or not. I don’t know. I wish we never changed. I don’t know.

I stayed in contact with ___ throughout fall and winter. Staying. We are good friends, really. He sends me pictures of autumn leaves, random screenshots, and stupid jokes we like. We listen to music together sometimes. He tells me about girls. I advise. I tell him about guys. He advises.

Snowing now. I think about sending ___ a picture but then I decide against it. It falls onto my shoulders, my nose, the crown of my hair. This snow won’t stick. It smells like water. It smells different. I tread lightly.

AFriends surrounding me, a glass at hand—empty, near closing time. During the hassle where everyone tries to figure out a way to get home, I grow distant. It is my last day here, but I don’t want to leave. Everything I have

seeds here, but we are growing apart with every coming day. I am afraid. Of being alone.

I start walking back home. Not exactly sure where home is actually, now in a life fractured across countries, cities, and divided with an ocean. One

inadvertently slips into a dreamlike state when one knows the streets of a city so well. The mind is able to wander somewhere else. In a simple–minded way, I am hoping that I will encounter her. With every corner I turn there is that unstoppable burst of excitement and anticipation that maybe, this

corner is the one where she appears. The wave of energy withers away with every failed attempt, but stubbornly flowers again as if it didn’t fail me for a hundred times. Under the lights of the city, with the warming comfort of a bit of wine inside keeping me from shivering under the cold night, I walk downhill. Maybe I text her, I think to myself. For some reason it doesn’t feel right. Lacks in romance, how I feel right now needs another way of communication. A letter? Who even writes a letter? I would regret that tomorrow morning. She lives far away now. I remember her face clearly. Every detail memorized, buried deep. A flower shop that is closing nearby, a restaurant with a small roundtable with two chairs outside at the corner of the street. So many faces, too much sound. Reality sinks and memories flood in. I imagine us in these places; I want to tell her about the movie I watched yesterday and how I hated that it was so well written but so badly produced. The artist she recommended, I actually liked his second album more than the last one. In this field where imagination and memories meet, I miss her.

My friends tell me to download Tinder. “Aren’t there prettier girls where you go?” The concept scares me. To have the most perfect photos, seem like the most fun and most attractive and most lovely and most. Then getting erased and brushed off by one swipe? But no, I love things about her that I don’t like. Her breath smells of coffee (you guessed it, I hate coffee). She takes up too much blanket. She doesn’t give things time, loses interest a bit too fast. She always tells me to decide the movie, but we end up watching what she picks. She sometimes makes affection look like obsession and blames me for it. I love her.

When you can’t pinpoint a certain place, a house, a couple of your belongings, or a neighborhood as home, you resort to people. It is its own kind

“My love, my queen, my broken dreams come save me,

Kiss me like the wind,

Won’t you kiss me from within?”

– sufjan stevens, “My Red Li le Fox”

of pain. People told me that studying abroad would be full of sacrifices. Sleepless nights, not having warm food on the stove, jetlag, those I could bear. But no one told me what to do when you miss your home. Maybe I will put a

couple posters up. The recipe my mom sent from WhatsApp could do the trick. But what turns it all into a home is love. What does all of it mean if you don’t have someone to share it with? I should call her. I look at the time, 12:17. That’s five in the morning where she is. Can’t do it. It doesn’t happen as often now, but when I lose my interest in Philadelphia, all the colors of the city start fading. Faces and names get mixed up, I grow distant. Too many strangers. Why can’t she be here, why can’t I be where she is? Why can’t I just think of something else and stop the idea from crawling back up to the surface? This language I write in feels strange, feels like a bouquet of random letters emptied out of any meaning. I hate her. These thoughts carried me home, and now I am at the door. What to think of now? Of love or its absence? Maybe what to put in the luggage I need for tomorrow. Trying to focus on what is real now, those tickets are expensive. But, real? Oh, how I detest that word. So devoid of imagination. She is a dream for me. I live in that dream, and that dream lives in me. Life has thrown us into different corners of this world, and I can’t help but think of her while rummaging through all my stuff. The clothes spread across the bed and the floor blend into the walls of my room, a museum of the person I used to be. The boy who used to wake up in this bed everyday dreamed of her. I dream of her.

I want to tell her that even though we got separated, at distant places and times, I love her as much as the day I met her. FaceTime, movie watch party, anything to keep this garden alive. Perhaps, they are futile devices. I have an image of her burrowed in my mind of the time she took me to her favorite place, under a yellow light, to drink coffee. Her dark red nails, long hair, brown eyes, perfect smile. Can’t help the image spurning from within.

Read more om the Love Issue on page 18.

From the sports stadiums to the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, workers are demanding to be paid their worth.

BY SARAH LEONARD

Photo by Abhiram Juvvadi

On Monday, Sept. 23, two different red signages mingled with the crowds outside of Citizens Bank Park. There was the typical Philadelphia Phillies red, donned by excited fans to cheer their team on against the Chicago Cubs; and then there was the bright scarlet of solidarity and unity, displayed on shirts and signs of striking Aramark workers. Even under grey, rain–threatening skies, the spirits of fans and striking

workers alike weren’t dampened. Chants of “If we don’t get it? Shut it down!” and “What do we want? Contracts!” rang through the air, all under the watchful eye of the iconic, inflatable Scabby the Rat.

Stadium workers are only some of the latest to join Philadelphia’s picket lines: The city has historically been a leading city when it comes to labor militancy, and the past few years have seen a

reawakening of worker organizing. A few recent examples include transit workers striking against SEPTA, the six–week strike by Temple University graduate students in January 2023, and Pennsylvania’s first union of training doctors (and the largest union the city has seen in decades!) formed by fellows and residents in the Penn health system. Even the favorite local coffee shop/study spot, the Green Line Cafe, unionized with PJB/

WU Local 80 this past summer.

Perhaps some of the most remarkable progress has been made on the steps on the Philadelphia Art Museum: After an epic 19–day strike in 2022, the PMA Union ratified its first contract and secured essential rights like parental leave, minimum hourly wages and salaries, and longevity pay (though the $500 raise for every five years employed at the museum came into question this past summer when the contract was interpreted differently by museum management).

The movement sparked in 2019 with simple worker–to–worker communication. A Google spreadsheet, created by Michelle Millar Fisher of the PMA, listed the title, organization, salary, and benefits of museum workers not just in Philly, but at museums worldwide. It highlighted the vast differences in what workers earn for very similar jobs and created the kind of transparency essential to questioning the system and making change.

“I’m sure it’s not unique to us, but the departments were very siloed. So if you’re having problems with your job, you’re kind of like, ‘Oh, it’s just that my manager is kind of crappy or my situation.’ And I think people started talking cross–departmentally and realized, ‘Oh, this is like happening with you guys. Oh, the same issues are happening.’ And I think that started a broader conversation about the systemic issues,” says Matt Carrieri, executive board member at large at the PMA Union.

Stagnant pay was one of the most glaring issues at the PMA. Employees who had dedicated years to the museum weren’t seeing that reflected in their paychecks, even as the cost of everyday necessities skyrocketed around them.

“[They weren’t] rewarding people for years of service and dedication. I mean, people worked through the pandemic. People worked through the financial crisis of 2008. … They have institutional knowledge that stays in the museum,” says Carrieri, who has seen a more than $5 raise in the past few years with union negotiations, compared to a mere 55 cent raise in the three years before.

So what do workers do when raises and benefits are being withheld and employers are slow to negotiate? They actually don’t go on strike just yet; there’s a very specific process to make sure that the majority of union workers are on board and that employers are aware.

Strike votes are an essential first step: Unions need to make sure that enough workers are willing and prepared to walk off the job and possibly go without pay for a little while. If the majority vote in favor, they’ll go on strike watch, and maybe hold a one–day strike. All of this is done in full view of management and the public to garner support and show management that they’re serious.

The resurgence of local labor organizing makes it clear: Philadelphia remains a city of the worker.

“That one–day strike lets them know what the museum is going to function when the workers aren’t there. [It] shows them our labor is valuable,” explains Carrieri. “All those things are to avoid a strike. That’s the last thing you want to do. No one wants to strike.”

It’s a big risk for workers. There’s a temporary loss of income and the potential of losing the job entirely. Luckily, the fight for workers’ rights in Philadelphia is not a lonely one. Even before PMA workers officially went on strike, they had $35,000 pledged from the Teachers’ Union, the Firefighters’ Union and AFSCME.

What followed was two–and–a–half weeks of picketing and continued back–and–forth contract negotiations, all leading up to the grand opening of the museum’s Matisse in the 1930s exhibit.

“That was on purpose; you want to disrupt as much as possible,” says Carrieri. And the pressure paid off: PMA workers

walked away with basically all of their demands met, from paid parental leave to minimum hourly wages and salaries and longevity pay.

What’s behind this sudden uptick in worker activity? The pandemic certainly set things off, but there were murmurings of labor organizing even before that.

“I think young people have seen the benefit of collective bargaining and being able to speak with one voice,” says Yvonne Harris, president of Local 590, which represents workers at Penn Libraries. Especially in more professional, white–collar fields, which might not have been associated with union organizing in the past, people are seeing the advantages of unionizing: Following in the footsteps of PMA workers, cultural workers across Philly and the nation have begun unionizing and negotiating contracts.

Philly’s cultural institutions, from the Philadelphia Zoo to our very own Penn Museum, have seen workers form unions and begin negotiating contracts in the past few years. In 2023, the Please Touch Museum (where 95% of union workers make less than Philadelphia’s living wage) became one of the nation’s few unionized children’s museums. Other unions, specifically those in Philly Cultural Workers United, have voiced support for workers fighting for a fair contract.

“I think it’s helped other people realize their worth and their value and what they can accomplish together. … Seeing all these other institutions joining with us, that just gives us that much more power and ability to advocate for ourselves. I’m pretty hopeful. I mean, it’s an endless fight, but yeah, I’m hopeful,” says Carrieri.

“It is the goal of the union movement to grow the union movement. So a lot of energy and funds and efforts are being put into actually moving that goal forward. I do see this as being just a beginning and that we’re going to see a lot of growth,” adds Harris.

The resurgence of local labor organizing makes it clear: Philadelphia remains a city of the worker. k

Your "problematic fav" is a real life criminal.

BY DIEMMY DANG

She scammed hotels, banks, and friends out of hundreds of thousands of dollars. She was convicted on one count of attempted grand larceny, three counts of grand larceny, and four counts of theft services. She served almost four years in jail, including time at Rikers Island. Six weeks after her release, she was arrested by United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement for overstaying her visa. And recently, Anna Delvey appeared on Dancing With the Stars—wearing a bedazzled ankle monitor.

Delvey, whose real name is Anna Sorokin, gained a reputation as one of New York’s most infamous con artists by posing as a wealthy German heiress. “Anna Delvey” was yet another lie that Sorokin created, part of an elaborate ruse that granted her access to the inner circles of the city’s social elite. Although Sorokin was born to middle–class parents in the Soviet Union, she gave conflicting accounts of her background that sometimes identified her father as a wealthy diplomat, oil executive, or financier. In reality, Sorokin’s father was a truck driver and HVAC business owner.

The persona that Sorokin formed for herself was characterized by glamor, excess, and exclusivity. Sorokin lied about having a

$60 million trust fund, using fake financial documents to support the lavish lifestyle she led in New York. She stayed at luxury hotels, chartered a $35,000 private jet, dined at New York’s most upscale spots, and claimed to party with celebrities like Macaulay Culkin and Derek Blasberg. The smoke and mirrors Sorokin shrouded herself in allowed her to borrow and never repay large sums of money from her wealthy friends, mounting unpaid bills as she climbed further into the lifestyle of a socialite.

After Sorokin was arrested in 2017 by the Los Angeles Police Department, her case granted her a level of fame even beyond the one that she had previously cultivated for herself. The public was captivated by the opulence and ridiculous nature of her fabricated life, causing Sorokin to become a media sensation. Tabloids continuously ran articles on her, podcasts like Alex Cooper’s Call Her Daddy hosted her, and Netflix released the show Inventing Anna inspired by her.

Amid the media frenzy, it became easy to forget the implications of what Sorokin had done. The fact that she was a convicted fraudster who was found guilty of eight theft–related charges became a lighthearted detail, diluted by the TikTok edits, custom

T–shirts, and YouTube videos that people made about her. Most recently, social media has been populated with videos of Sorokin’s appearance on Dancing With the Stars, where she was one of the first celebrities to be voted out of the show.

The media’s coverage of Sorokin’s reaction to her elimination is further proof of the level of celebrity status that she’s achieved. After being asked what she would take from her experience on DWTS, Sorokin responded with simply: “Nothing.” This one–word response incited a new burst of tabloid and news coverage, additionally leading Sorokin to be hailed as “iconic” on social media by people like DWTS co–host Julianne Hough.

The treatment and glamorization of Sorokin demonstrates the powers that media has to shift narratives, causing a desensitization to the true weight of events. This alarming notion has manifested itself in the online reception of other controversial figures. Gypsy–Rose Blanchard, for example, rose to worldwide fame when her story of alleged abuse and eventual involvement in her mother’s murder came to light. Blanchard’s mother, Dee Dee Blanchard, had subjected her to lifelong physical, medical, and mental abuse. After developing an

online relationship with Nicholas Godejohn, whom Blanchard met on a Christian singles website, Blanchard and Godejohn conspired to kill her mother in an effort to escape her control. In July 2016, Blanchard was sentenced to ten years in prison for the murder of her mother.

Upon her early release in December 2023, Blanchard was greeted with an onslaught of media fanfare and attention. Blanchard’s presence in the influencer space only added to the commotion. Almost immediately, she began posting on platforms like Instagram and TikTok, sharing videos about post–prison life that went viral. Clips from Blanchard—where she talked about her boyfriend, participated in TikTok trends, or showed off her makeup routine—were reposted and edited by a plethora of digital audiences. Social media users made memes centered around Blanchard’s entry into internet culture following her release, with some even creating T–shirts mocking her.

The propelling of figures like Gypsy–Rose Blanchard and Anna Delvey into pop culture prominence effectively allowed the weight of their stories to fade. This idea has been increasingly demonstrated online. Cameron Herrin—convicted of killing a mother and daughter while street racing—has been the subject of a myriad of TikTok edits, with fans making Instagram pages (captioned #justiceforcameronherrin) where they claimed he was too handsome to be incarcerated. The Menendez brothers—victims of intense abuse at the hands of their father, who they eventually killed—inspired the Netflix show Monsters. This past Halloween, costumes of the brothers circulated online.

A concerning pattern has emerged as the oversaturation of social media content causes an emotional detachment from the true gravity of real–life events. Rather than recognizing the moral complexity of these figures’ actions, social media transforms them into pop culture celebrities, allowing their stories to become fodder for trends, merchandise, and virality. This online phenomenon demonstrates a troubling side of the internet: its power to trivialize, commodify, and sensationalize real–life experiences of trauma and harm. k

20

weike wang ’s rental house reminds us of the opportunity cost of belonging

How do we know where to call home?

22

rethinking marriage in the modern age “Something old, something new.”

27 love in the age of sampling

In defense of borrowed brilliance and why you’ve de nitely danced to it before.

29

4b isn ’t breaking up with men—it ’s breaking up with the system e 4B movement isn’t a bold feminist statement; it’s a quiet surrender to a system that leaves no room for love, family, or dreams.

32 loving by number s Romantic vs. platonic: ich love is more on our minds?

How do we know where to call home? ses

BY SAMANTHA HSIUNG

Design by Erin Ma

What is the price that we pay to live in America? How far will we go to understand and help those that we love, even when they don’t reciprocate love in the way that we need? Rental House by Weike Wang, a Creative Writing professor at Penn, explores these questions by following a couple—Keru and Nate—and their delicate relationships with their family and the world around them.

Keru and Nate are a “DINK” (dual income, no kids) couple in their mid–thirties who met as undergraduates at Yale. Keru is Chinese American, with parents who immigrated from China to the United States, while Nate is a “poor white from nowhere” who a ended Yale on full nancial aid. As a corporate consultant, Keru is money–focused and ambitious, yearning to build a life that ful lls the American dream to oset her parents’ sacri ces of coming to the country. Nate stands in diametric contrast: He’s an assistant professor of science at a private college who’s complacent with his modest income. e novel follows two vacations that the couple embark on: one in Cape Cod and one ve years later in the Catskills.

Wang is skillful in creating sharp, incisive observations of family dynamics. She cra s characters who not only feel intimately familiar to children of immi-

grants but also o er a sense of connection and recognition to anyone who has had to navigate the intricacies of family relationships. is strength of her writing becomes ever–apparent from the moment we are introduced to both Keru and Nate’s families in Cape Cod.

Keru’s parents visit the Cape Cod house rst, taking no time to comment on “small imperfections” of the house, like the “narrowness of the driveway, the lack of a garden hose,” subtly revealing their perfectionist tendencies. Conversations revolve around predetermined topics, like careers and kids that Keru hasn’t had yet.

e family has no boundaries and every opinion is spat out at the dinner table— except for Keru’s. She feels sti ed around her parents, like a mere “listening board” who is “not expected to have opinions of her own.”

Nate’s parents soon arrive at the house a er Keru’s parents leave. Unlike Keru’s parents, they are too nice to Nate, greeting him with pleasantries. is niceness, though, cannot be con ated with mutual understanding as Nate and his parents disagree on their core values and beliefs. His parents are anti–vax, pro–Trump, and insistent Nate reaches back out to his brother, with whom he has a sordid past. Nate argues back at them to no avail.

Nate’s mother, speci cally, “demand[s]

to be understood by everyone around her, yet was not willing, ready, or able to extend the generosity to others.” Like Keru’s parents, Nate’s family circles back to conversations about children: “Most adults on this planet are parents, and to understand most adults and your own parents, you must become parents. Else you will never understand anything, Nathan. You will be completely oblivious to everything that’s good.”

Five years later, the couple ventures to the Catskills in the vacation that becomes the centerpiece of the novel’s second half. is time, it’s just Nate and Keru in a quaint bungalow with no parents. ey meet a neighboring European couple— Mircea and Elena—who critique American culture and label them as a “DINK” couple. Wang keeps the story unexpected yet cohesive by introducing elements from earlier plots such as Nate’s estranged brother, who manifests at the bungalow asking for a large sum of money.

Here, Wang o ers us even further in sight into the couple’s lives, peeling back the layers of their relationship beyond the problems they face with their families. Mircea questions Nate in ways that beli his manhood, telling him that “teachers have no power” and that he should “buy property and take be er care of [his wife].” Elena gawks about how she has met sever

al “one Asian, one white” couples and how marrying outside the racial group causes kids to become less “cohesive.”

ese external judgments re ect the critiques that Nate and Keru had received from family in prior parts of the novel, but hearing them from outsiders make the verbal a acks far more wounding. is is the sad reality of adulthood— that existential crises are recurring and vulnerabilities become more exposed. Wang unravels these con icts like an onion, stripping away layers swi ly and precisely, until the raw, stinging core is laid bare.

At its very core, Rental House is about rental houses in a literal sense. But it’s also about the metaphorical concept of rental houses—what it means to not feel a sense of full belonging in a space where someone else has every right to feel like they fully belong. For Keru, her identity as a Chinese American renders the United States her rental house; her constant grappling with her nationality and ethnicity is the cost of rent—an unavoidable toll that she must pay to live in America. No amount of money that she spends on either of her rental houses can fore

she and her parents are and if “they enter[ed] the country the right way.”

But even her place within her family seems ckle, rented perhaps, as she struggles to connect to her parents, describing them as “claw–parents” who leave holes in her chest. Nate, too, o en feels misplaced in his own family, di ering with them on his politics and core beliefs. ey cannot understand why he chose a job as a professor when he would “make a be er lawyer than scientist.” Both families push Keru and Nate to have children even though neither of them want to.

e theme of su ering permeates every corner of this novel, complicating the characters’ sense of existential meaning. Keru’s mother believes that “su ering is required.”

“To su er is to strive and to set a bar so high that one never becomes complacent. To become complacent is to become lazy and to lose one’s spirit to lose one’s spirit to su er is to live,” she says. is philosophy begs the ques tion: How many bruises, marks, scars can someone take before su ering reaches its capacity? at exactly is so wrong about

accomplishments? Wang provokes ideas that linger long past the novel, causing the reader to wrestle with the delicate balance between ful llment and su ering, and to reconsider what it truly means to live a life worth remembering.

Rental House concludes on an abrupt note, with Keru and Nate contemplating whether they should go to the hospital a er Keru breaks her ankle. ey’re now pushing 40. We have seemingly watched them throughout the years, beginning from college, with Wang’s quiet transitions between past and present, memory and reality. eir story is not neatly resolved, but this ambiguity is intentional.

Life, like a rental house, is replete with transience and impermanence, and it is up to us to assign meaning to our lives and the spaces that we inhabit. We catch only fragments, a eeting segment of Keru and

“Something old, something new.” ses

BY NORAH RAMI AND JULES LINGENFELTER

Design by Dana Bahng

IPROBABLY WOULDN'T BE married if I knew I was going to have health insurance. at’s not because I don’t love my partner and [don’t] want to spend the rest of my life with him. It’s because I didn’t want to actually take part in this institution,” says Miranda Sklaro , a Ph.D. candidate in political theory at Penn. Sklaro knew she and her partner wanted to have kids. But she had concerns about healthcare, which she wasn’t sure Penn would provide. “It was just something we had to do.”

In 2004, the United States Government Accountability O ce recognized 1,049 rights, bene ts, or privileges associated with marriage as part of the Defense of Marriage Act, which a empted to codify the de nition of “marriage” as a “legal union between one man and one woman as husband and wife.” ough

this codi cation of strictly heterosexual marriage as legally valid was determined unconstitutional in 2013, the bene ts and rights outlined by the GAO—such as healthcare and inheritance—are still directly tied to marriage. For many individuals, marriage is an economic necessity and a legal institution that they must opt into, regardless of their personal feelings.

It seems regressive—a relic of a bygone era—to imagine marriage as an economic means of survival rather than a celebration of love and compan-

ionship. ile people easily admit to choosing to work on the basis of economic stability, it feels uncomfortable to admit to choosing marriage for the same reason. Yet, at the same time, it’s di cult to justify a lifelong partnership as legitimate outside of marriage. From e O ce’s jokes about Pam’s endless engagement to reality TV shows like e Ultimatum, Western culture sees a successful romantic relationship as ending in marriage.

It’s di cult to disentangle the idea of marriage as an economic unit created by the state from our ideas around love and companionship. But the con ation between the two is a relatively new concept. roughout much of history, marriage was viewed as akin to a career—an economic necessity to ensure the continuation of one’s wealth and preservation of their property.

“ e idea of marrying for romantic love emerged as a signi cant cultural force in the 19th century. Yet marriage was then still an economic proposition, just a culturally disguised one. e way the state structures marriage today makes it inescapably an economic proposition,” says Caz Ba en, an English and Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies professor at Penn.

But Ba en contends that because of this romantic makeover of marriage, marrying with the intention of money is taboo. One must buy into marriage as an economic necessity, but they cannot be entirely honest in these motives without appearing heartless, cold, or even earning the label of “gold digger.”

e way individuals conceptualize companionship is directly connected to the state’s economic and legal incentives

for marriage and the nuclear family.

“These systems are designed precisely to prioritize marriage as the predominant mode of companionship, and to thereby promote the nuclear family—heterosexual, married par -

ents with children—as the fundamental social unit and as a replacement for the social safety net that has been systematically eroded in the United States since the Reagan years and the rightward turn of the 1980s,” says Batten. In other words, the burden of survival has been placed on the nuclear family. It seems the best way for an adult to guarantee that they are included in a family unit and have a modicum of security is to get married.

A 2013 study by e Atlantic nds that unmarried individuals pay upwards of $1 million more in their lifetime for healthcare, taxes, and living expenses than their married counterparts. Choosing to operate outside of marriage—whether you live with a long–term companion or a group of friends—is a privilege of its own. “You have to be nancially independent, employed with decent health insurance, and healthy and able–bodied to be able to build companionship outside monogamous, heterosexual marriage because so many forms of care and support are only made available through the nuclear family,” says Ba en. e economic and legal incentivization of the nuclear family and marriage makes it di cult to conceptualize companionship outside of marriage. “ e state has required it to be that way,” says Nancy Hirschmann, a Political Science professor at Penn and the author of e Subject of Liberty: Toward a Feminist eory of Freedom. “ e state has structured the parameters so that thinking about love in di erent ways becomes foreclosed.”

Some individuals, frustrated or unsatis ed with the limitations of our contemporary ideas of marriage, have started to question what it means to rethink companionship beyond gathering in holy matrimony.

“Opting out of marriage also allows one to break away from the constraints

and limits of the nuclear family—which is too small a unit to e ectively shoulder the burden of care the state has abandoned,” says Ba en. “Opting out of marriage might allow one to build other kinds of community that spread the bur-

den of care out in more balanced, achievable ways.” For those who don’t have the ability to remove themselves from the institution of marriage entirely, there are a empts to pursue alternative forms of marriage that work for their individual needs.

Some are attempting to utilize marriage to legitimize relationships outside of romance—popularizing the term “platonic marriage.” On June 1, 2024, best friends Sherri Cole and Ellen Moore legally married after three decades of friendship. The two women met in 1992, moved to South Jersey together, and bought their first house in 2000. Though their relationship remains strictly platonic and both women identify as asexual, they are committed to each other as life partners: Marriage

was a means of legal protection, particularly concerning healthcare and home ownership. “What matters to us is friendship, kindness and support,” Cole says in an interview with The New York Times. “That is what we are to one another, and that is—or should be— the core definition of a ‘marriage’ and ‘partnership.’”

In April 2024, a Times article titled “Lessons From a 20–Person Polycule” went semi–viral as a salacious look into an unconventional, polyamorous relationship. ough much of the piece delves into the complexities of the polycule, the topic of marriage nds itself woven throughout, with many members being married to another partner. “A lot of people are married and have primary partnerships. ey’re coming to it from the opening of a monogamous relationship,” says Katie, a member of the polycule.

Another member, Nico, explains that “[t]here are so many things we’re pushing against, but we still have to live within. My husband and I married for legal bene ts, for taxes and things like that. Our society’s laws bene t married people.” But Nico follows up on the possibility of marrying her girlfriend as a means of demonstrating their commitment. ough not legal yet, Nico says, “In Somerville, which is the city right next to mine, the city legally recognizes multiple domestic partners. I think our society is moving toward that, but it’s a slow process.”

In the past year, media surrounding restructured marriages, or alternative companionship, has become increasingly popular. e 20–person polycule may be the most popular example, but there are a slew of pieces highlighting how others are choosing to rethink what marriage is, perhaps hinting at a larger cultural shi .

“As [non–monogamy] gains, I don’t even want to say popularity, I almost think it’s visibility more than anything, but also, as it gains more acceptance and more people are willing to talk about it … [i]t’s just naturally occurring that

c“The beauty of non or open relationships, the foundation, is that one person literally cannot be your everything. That’s why we have friends and family and everything else. But we tend to zone in on a partner and be like, ‘This person has to be my everything’ in a relationship sense.”

we are nding ourselves in more non–monogamous communities,” says Jay Shifman, a local Philadelphia resident. He mentions his volunteering at the Wooden Shoe, an anarchist bookstore in South Philly, and its inability to keep

e Ethical Slut, a self–help guide to polyamory, stocked at the store. He and his wife Lauren Shifman are in an open marriage and are part of a polycule.

“We started out with a very traditional or conventional marriage,” says Lauren. “You date, and then you love each other, and then you get married. You’re monogamous, and that’s what you do.” But Lauren and Jay do not describe themselves as conventional people. ough they loved each other and similarly felt a desire to be lifelong partners, there were gaps in the relationship not being lled. Both Lauren, who identi es as queer, and Jay, who identi es as polyamorous, felt there was a “struggle to t into a one–dimensional relationship” with these identities in mind.

A couples therapist o ered them the potential solution of exploring an open marriage, one that they ultimately chose to pursue. “We were starting with what felt like somewhat of a blank slate where we could go kind of point by point and cra the marriage we wanted,” says Lauren. “Our starting place was like, we want to be life partners, we want to share a home, we want to have these sort of core things that we do together in our partnership.” From there, it was up to the couple to decide what exactly this new avenue of romance would entail.

“ e beauty of non or open relationships, the foundation,” Jay says, “is that one person literally cannot be your everything. at’s why we have friends and family and everything else. But we tend to zone in on a partner and be like, ‘ is person has to be my everything’ in a relationship sense.”

e ability to rely on multiple, rather than one, has lessened the practical issues that arise in any potential relationship while heightening the shared experiences of partners. For example, Jay’s girlfriend owns cats, to which he is

allergic, but they never fret over an incompatibility that in a monogamous relationship may lead to breakup. Similarly, Jay and his girlfriend bond over their love of writing, a hobby Lauren does not engage in. On the other hand, both Jay and Lauren love to travel together, while his girlfriend does not. ough seemingly arbitrary, it is these small things that allow Jay and Lauren to feel ful lled in various facets of their life without relying on one partner to check every box. Jay and Lauren have been married since 2018. ey are open about the struggles that come with opening one’s marriage and the importance of establishing boundaries and creating a precedent of constant communication. ey are also adamant that there is no one–size– ts–all solution to any marriage, and what works for them will not work for others. But they are happy. “We’re still married and the openness is going well,” says Jay.

But rethinking marriage isn’t necessarily radical or political action in and of itself.

“I don’t know that marriage itself—a contract between two people that codi es them as a legal unit in the eyes of the state—can be rede ned or made radical,” says Ba en. “ at’s not to say people shouldn’t get married; there are many compelling reasons two people might get married, especially given the protections marriage o ers, and given that the fastest way to have a relationship recognized as culturally legitimate, to have it respected, to ensure the participants can protect and care for one another, is to get married. But the institution itself as constructed by the state is inherently non–radical, inherently conservative.”

In many cases, the marriages and arrangements we de ne as “unorthodox” or “alternative” aren’t necessarily new but derive from historic practices that

precede our modern age. In medieval England, there were records of chaste marriages between members of royalty who were married for merely geopolitical reasons. e ancient Indian myth of e Mahabharata centers on a woman

cIn many cases, the marriages and arrangements we define as “unorthodox” or “alternative” aren’t necessarily new but derive from historic practices that precede our modern age.

married to ve brothers—of which some have additional wives as well. Prior to Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015, there are accounts of gay men and women marrying each other as friends in what are considered “lavender marriages.”

“We can create these alternative forms, but a lot of times, they don’t actually disrupt the hegemonic ways that relationships work. Just opening up your marriage in itself, or being poly in itself is not actually supportive of politics. It might be counter–cultural, but it’s not necessarily counter–hegemonic. ere are new ways of doing the old things,” says Sklaro .

Yet, these so–called “alternative” arrangements force us to denaturalize the modern conception of the nuclear family and reconsider the ways in which we form and prioritize relationships.

“Rethinking marriage is the only way to get at the destabilization of neoliberalism and the move that we’re making towards oligarchy. I’m convinced that it has to start with rethinking the family and changing it from this possessive, insular, take–care–of–your–own model,” says Hirschmann. “If we focus on love, a whole realm of di erent options open up to the family. Collections of mothers and children who aren’t necessarily sexual partners. Families can be de ned as groups of friends who cohabitate. Families can be de ned as polyamorous or di erent sexualities, and di erent identities. It’s about thinking di erently about the place of love in the family, and trying to resist, or being conscious of and resisting, the ways in which families are divided as economic units,” continues Hirschmann.

Over the last 50 years, the marriage rate in the United States has dropped by nearly 60%. In many cases, this trend is attributed to an increase in financial opportunities and independence for women, who are no longer forced to depend on marriage as an economic necessity. Yet, this decline has been highly politicized—depicted in many cases as a decay of our social fabric that can only be solved by attaching even more eco nomic incentives to the in stitution. As the state plac es an increasing emphasis on preserving “family values,” it’s important to consider where that value comes from and how it can be considered on its own terms.

In defense of borrowed brilliance and why you’ve de nitely danced to it before. ses

BY SOPHIA MIRABAL

Design

by Insia Haque

If i were to mention “ funky Drummer,” you might furrow your brow in unrecognition, or you might be trying to decipher what combination of sounds could warrant the title. Is the drummer funky because he smells weird? Or is it a nod to his unparalleled groove? Chances are, you wouldn’t recognize

the track’s appeal or mid–20th century cultural significance, nor would you be familiar with its creator. In the hip–hop world, the eccentric James Brown is widely considered to be the most sampled artist of all time. Alongside iconic hits like “Funky President (People It’s Bad)” and “Get Up Offa That Thing,” he penned “Funky Drummer”

during a successful career that spanned the ‘60s and ‘70s. But if you’re just not cool enough to keep up with Nixon–era disco, chances are you are familiar with its borrowers.

Kendrick Lamar’s “XXX.,” Dr. Dre’s “Let Me Ride,” and “3005” by Childish Gambino all hail from the three aforementioned, oddly named tunes.

Brown’s work has been spitting inspiration into the music of modern artists since the ‘90s. It’s a hefty legacy, and I wonder: If you were to ask this personality what he thought of his recycled melodies, what would he say? Would he feel cheated out of a half century of musical finesse and creativity, or would he smile at his influence and feel appreciated? There’s no real way to know. (Though realistically, he’d probably throw up his arms in signature style, donning a sequined jumpsuit, and tell you he couldn’t care less. What a guy.)

Love in the “age” of sampling might best be understood as a kind of musical flattery, though its gesture can mean many things. Even “age” is a rocky description. Early remix culture dates back to the early ‘80s, when Fairlight users like Kate Bush and Peter Gabriel gave popular music of the time that fuzzy, sparkling, glimmering sound we associate with late–20th century production. Their techniques turned to MPC mixes and built the blocks for the cut–up nature of sample–ridden genres. It was an inclusive gesture, and suddenly, elaborate tracks could be formed, preserving longer passages of music within new tunes, by artists without studios or formal music knowledge.

But regardless of what Brown would think, sampling as a legitimate (or fair) form of musical expression remains some topic of debate. This is especially true when we consider the electronic and hip–hop industries, which, having embraced the modern audio sample, have become an easy target for critics. It begs the question: Is sampling a rejection of novelty or the greatest contemporary love letter? The less tolerant might stick up their nose at the trying and taking of sound from older creative work. They couldn’t be more incorrect. In truth, it’s an art form in itself—a springboard, an homage to musical trailblazers.

And it’s not only flattery that justifies. Sure, there’s a way to write off sampling

as inspiration—a reusing and recycling so as to introduce the audience to timeless melodies and leverage the work to

cIn truth, sampling is an artform in itself—a springboard, an homage to musical trailblazers.

esupport a novel production. There’s another way of looking at things, one that considers the delicate relativity

of artistic creation. Musical interpretation is a crucial form of musical understanding, generally. By interpreting the music, we internalize it and imbue it with our own expression and meaning. Sampling, as a rule, makes space for that alternative interpretation: using recordings as raw material for new expression.

Sure, Beyonce’s (conveniently titled) 2022 album RENAISSANCE was an homage to the plethora of progenitors she collaborated with, from Taylor Swift to Right Said Fred—their 1991 hit “I’m Too Sexy” interpolated on “ALIEN SUPERSTAR.” At first glance, the level of collaboration might make the record seem like the ultimate catch–all. In reality, something magical happens when you cross dancehall with Jersey club; dembow with deep house. The record, described as a “musical lair, a danceteria devoted to hedonism, sex and, most importantly, self-worth” by USA Today—which should tell you everything you need to know—doesn’t hail too far from the same mesh of electro hip–hop on “Fergalicious.” Because, let’s be honest, that’s way better than the 3000 songs it samples from. In similar fashion, Mario Winans said “eff it” when he formed “I Don’t Wanna Know,” because what else could have been the rationale behind inserting new–age Gaelic behind one of the most belt–worthy soul ballads of the early 2000s? It’s done so with a level of finesse and creativity that makes it stand on its own two feet.

Rather than viewing a track’s familiarity as a creative constant, sampling producers use it as a vector for new emotional associations. What’s clear is this: Brown’s sound didn’t just survive to see the music landscape of today’s world—it evolved. Blues–funk turned to end–of–century R&B to techno. And as we stand against a wall of critique and bitter accusation, the successes tell us everything we know: It was never about reusing. It wasn’t even about revival. It’s about repurposing.

e 4B movement isn’t a bold feminist statement; it’s a quiet surrender to a system that leaves no room for love, family, or dreams.

BY KATE CHO

Design by Kate Ahn

To the untrained eye , 4B looks like the next shiny feminist export: edgy, viral, and ready to be hashtagged into empowerment. In the United States, where girlboss feminism still clings to its dying breath, the 4B movement has been flattened into a palatable rejection of men and motherhood, a rebellious lifestyle brand made for Instagram captions.

But 4B isn’t a revolution; it’s a resignation. It’s the reluctant acknowledgement that in Hell Joseon—the satirical term for the unlivable, unforgiving hellscape that is modern South Korea—love, family, and ambition are mutually exclusive luxuries. And for most women, they’ve never been on the menu.

Western feminists have adopted the rhetoric of 4B without understanding it, the same way they once latched onto the Orientalist concept of “han,” Korea’s so–called “national sorrow,” to add a touch of exotic pain to their thinkpieces. In truth, han was weaponized by Imperial Japan and parroted by the Park Chung Hee regime, designed to keep Koreans enduring, silent, and compliant. Now, 4B is undergoing

the same erasure, reduced to a hollow statement of empowerment by women who have never had to choose between raising a family and preserving their dignity. 4B isn’t a feminist dream; it’s the nightmare you can’t wake up from, rebranded for an audience too detached to notice.

4B isn’t a feminist dream; it’s the nightmare you can’t wake up from, rebranded for an audience too detached to notice.

Hell Joseon is not a place but a concept—a bitter metaphor Koreans use to describe the beautiful, unlivable machine their country has become. The word Joseon harks back to Korea’s

last dynasty, a 500–year reign often romanticized for its Confucian values and cultural achievements but equally marked by hierarchy, rigid social roles, and suffering disguised as duty. To invoke Joseon in this modern context is to say that despite all the skyscrapers and K–pop idols, the soul–crushing constraints of the past never really disappeared; they simply got a facelift. In the United States, the word “feminist” is in the mainstream. It carries some respectability and even marketability. But in Korea, it’s closer to a curse, whispered with disdain or wielded as a weapon. Women who align with feminist ideals or movements like 4B face severe backlash: online harassment, workplace discrimination, and social ostracism. This cultural stigma makes the Western celebration of 4B as a trendy, feminist statement feel painfully naive. The United States lacks Korea’s entrenched hostility toward feminism, making it easier to romanticize 4B as empowerment without reckoning with the risks its adherents face. Corporate culture demands loyalty at the expense of everything else: health, time, even identity. Workdays stretch endlessly into evenings filled with mandatory drinking sessions,

where workers are expected to down soju with bosses and smile through their exhaustion. Men, after enduring military conscription that leaves them bruised in body and spirit, are expected to return as breadwinners. Women, even if they’ve climbed the same ladder, are expected to step aside, marry, and dedicate their lives to unpaid domestic labor.

And when there’s nowhere left to run, the machine still finds a way to squeeze. Korea has the highest suicide rate of any OECD country—a grim indicator of just how many people decide that death is the only escape. These are not isolated tragedies but systemic failures, as much a product of the nation’s structures as its glittering skyscrapers.

Hell Joseon may feel like a uniquely Korean tragedy, but its architecture bears the fingerprints of foreign hands. The United States loves to admire Korea’s resilience, marveling at its rapid industrialization while glossing over the cost. What it doesn’t acknowledge is how its own legacy helped lay the foundation for the misery it now pretends to pity.

During the Korean War, the American military didn’t just bring soldiers—it brought systems of exploitation. Camptowns (gijichon) erupted around U.S. bases, turning Korean women into commodities to satisfy foreign troops. These weren’t centers of empowerment; they were industrial complexes of despair, their foundations echoing the atrocities of Japanese “comfort women” camps. For the women trapped in them, there

was no choice, only survival. And when the war ended, these systems of abuse were swept under the rug—another compromise for a country desperate to rebuild at any cost.

The United States speaks of solidarity with Korean feminist strug -

gles, but its role in perpetuating those struggles remains unspoken. It celebrates sex work as empowerment while ignoring how it systemically imposed that labor on marginalized

women in Korea. It lifts up movements like 4B without acknowledging how its own policies exacerbated the conditions those movements are fighting against. Western feminism, with its glossy slogans and commodified narratives, doesn’t know what to do with the parts of history it helped create. It simply looks away.

The 4B movement—short for the rejection of biyeonae (dating), bisekseu (sex), bihon (marriage), and bichulsan (childbirth)—is not a war cry but a white flag. It’s a feminist response born from the constraints of Hell Joseon, where the idea of “having it all” feels like a cruel joke rather than a genuine choice. For Korean women, 4B isn’t about hating men; it’s about rejecting systems that demand they sacrifice everything and receive nothing in return. It’s not rebellion— it’s survival.

And yet, in the United States, 4B has been eagerly repackaged as a bold feminist stance, a trendy rejection of patriarchy that fits neatly into Western narratives. Here, the movement is reduced to its catchiest elements—“no men, no love”— and stripped of the pain, exhaustion, and resignation that define it. The push to adopt 4B in the West reflects a familiar pattern: a tendency to appropriate non–Western struggles without understanding them, flattening movements like 4B into a one–size–fits–all solutions for global feminism. But 4B cannot be understood outside the context of Hell Joseon, and in Korea, feminism itself is not an empowerment slogan—it’s a liability. What Western feminists often miss is that 4B isn’t a rejection of men—

marriage because these roles demand too much unpaid labor and emotional sacri ce, trapping them in cycles of exhaustion. But Korean men, too, are victims of this system. Military conscription demands two years of their youth, subjecting them to brutal hazing and psychological scars. e hyper–competitive workplace doesn’t reward their sacri ces—it exploits them. Men in Hell Joseon are breadwinners not by choice, but by expectation, crushed under the same cultural weight that breaks women.

4B doesn’t pit men and women against each other; it critiques a system that ties everyone’s hands. But when the

United States reframes 4B as an anti–male, anti–patriarchy stance, it turns a nuanced movement into a caricature of misandry. is framing not only erases the shared su ering in Hell Joseon but reinforces the false idea that feminism is inherently antagonistic.

For many Korean women, rejecting marriage, children, and relationships isn’t a bold choice—it’s a reluctant acknowledgment of a system that leaves no room for alternatives. e American obsession with “freedom” and “choice” misunderstands the core tragedy of 4B: the realization that the system doesn’t allow women to have it all. In Hell Joseon, a woman who chooses marriage sacri ces her career. A

woman who chooses her career forfeits her family. And a woman who wants both is punished by a society that demands perfection in every role but o ers no support for any of them.

4B is an obituary for dreams that Hell Joseon made impossible. It’s not a rejection of love or men—it’s a rejection of a system that asks for everything and gives nothing. And yet, in the United States, it’s turned into a lifestyle trend, a hashtag, a shiny export like K–pop and Korean skincare. is isn’t solidarity. It’s appropriation dressed as admiration, a failure to understand that 4B isn’t about empowerment—it’s about endurance in a nation that doesn’t let you rest.

BY NORAH RAMI

Design by Asha Chawla

Closing out the first weekend of my freshman year, my New Student Orientation best friend and I decided to do a post–frat McDonald’s trip (pre-renovation, that’s how old I am).

Over a shared box of McNuggets, he and I discussed our goals for college—he called them KPIs, in true arton fashion. ile I barely knew what I wanted to study, and much less who I wanted to be, my friend was already dreaming of his white picket fence. At the top of his list of goals was nding his future wife. “Once I go into investment banking, I won’t have

any time,” he explained. “So I need to nd her now.”

I pushed back. “ at does a wedding ma er if you don’t have a guest list?”