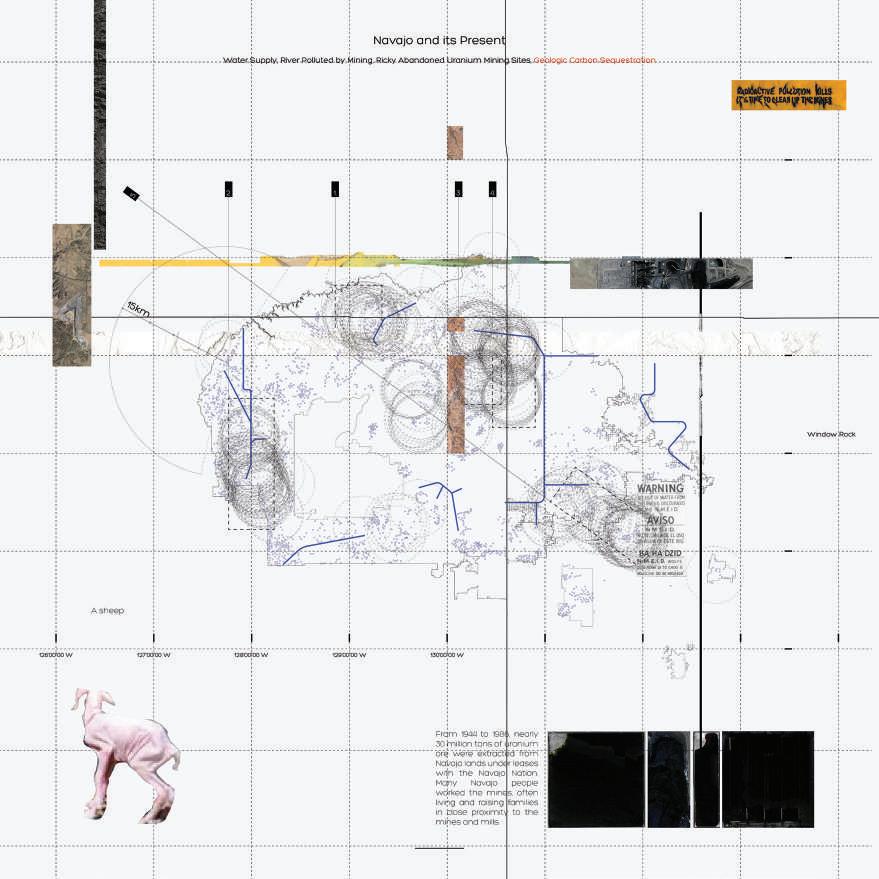

Rethink the Way of Occupying

Reinvention of Biochar that Brings Contamination from Uranium mines to be regenerated to building material

Sinyu Lin Advisor: Nina Sharifi

Sinyu Lin Advisor: Nina Sharifi

Masters of Science in Architecture: Design | Energy | Futures summer 2022

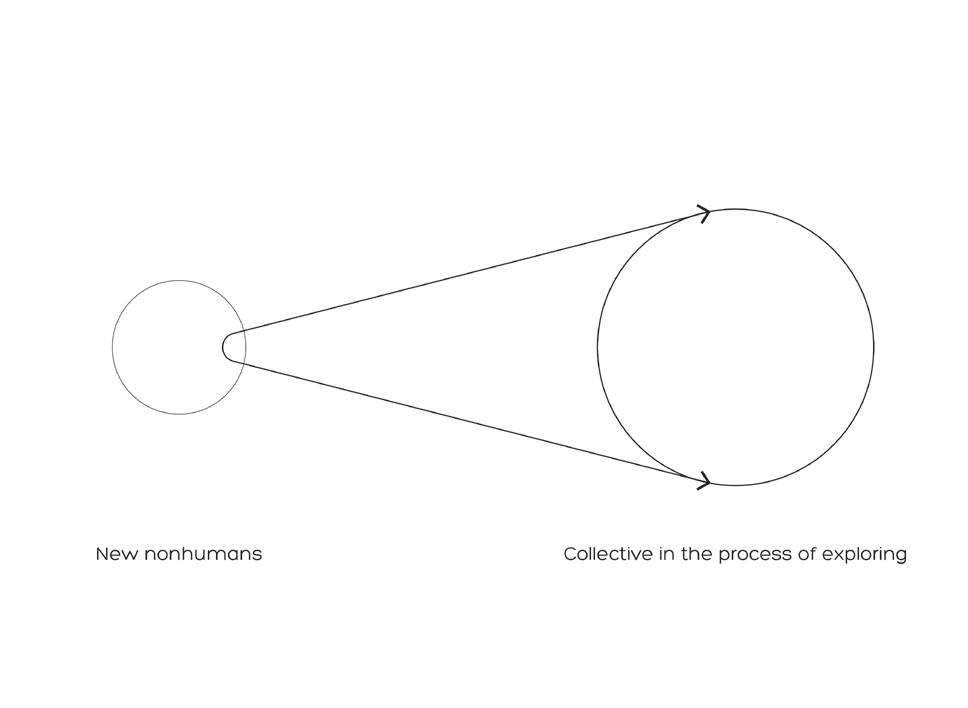

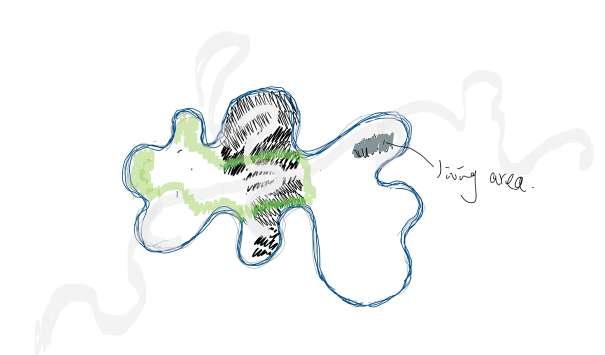

The goal of the research project is an action of reoccupying the land where has been contaminated by abandoned uranium mines (AUM), and of questioning the way how human being cruelly occu pies the land where we live. Abandoned uranium mine is a nega tive paradigm in which people strip the source they need but leave the contamination behind. The Navajo is one of the victims who have been struggling with this vast issue for decades. The contam ination has negatively impacted the Navajo on a daily basis. Live stock has been threatened because of the polluted soil and grass land in the grazing area, and water resource has been contaminat ed since the mining waste, including high acid liquid and liquid with heavy metal, was dumped to the land around the Navajo’s living place. Previous researches have pointed out that biochar could be a material that not only improves the soil texture for agriculture but absords heavy metal, high acid liquid, and contaminated earth. Introducing the biochar on site is not just providing a solution but seeing the way how biochar bring the contamination back to ma terial lifecycle. Two critical questions are: How do we reoccupy the contaminated land? What is the form of biochar that occupies an abandoned uranium mine?

keywords: abandoned uranium mine, radioactive waste, mining waste, reinvented biochar, interface, Navajo Nation, groundwater, high-acid liquid, land occupation

Abstract

1 ii

I see sculpture strengthened and finding through it the means of again becoming the great myth maker of human environment where man will find surcease from mechanization in the communion of mysteries and in the contemplation of enjoyment of a new freedom of spirit.

Isamu Noguchi, 1949

1. Rethinking the Way of Occupying

1-1_A Dam, an Uranium Mine, and a Bridge

1-2_Scratches on Mother Nature

2. Contamination in Uranium Mine and its Current Remediation

2-1_Goal of 1%: Evironmental Impacts of Uranium Mining

2-2_Current Remediations of Abandoned Uranium Mine

a. Improving Subsurface Cleanup Methods

b. Biochar Potential for Abandoned Uranium Mine Restoration

c. Northeast Church Rock Mine Remediation

2-3_Re-excavate the Contamination to Mix with Biochar

3. Precedents

3-1 New Notions of Occupying

a. Toyo Ito, Taichung Opera Theater

b. Tahan Architects, Louisiana State Museum

c. Isamu Noguchi, Contoured Playground

3-2 Different Techniques to Build with Biochar

Biochar Brick

Biochar Wall

4. Design and Fabrication

4-1_Formal Expressions of Biochar

4-2_Site Testing: Red Water Pond Road

and Mold Unit

a.

b.

4-3_Moduling

Bibliography Appendix 01 02 11 19 20 23 23 25 27 29 33 34 35 35 36 37 41 41 43 44 47 53 59 63 Contents iii iv

Rethinking the Way of Occupying

1-1_A Dam, an Uranium Mine, and a Bridge

It is inevitable that architecture needs a physical position in physical world. As Carol Burns envisions us1 it is time to rethink how architecture occupy a lot on earth. The site is commonly conceived of as a physical location, a plot of land connected to the earth and subject to its physical laws, within architectural concept and ap proach. The term “site” is frequently used to refer to a blank or in complete property that will be filled by an architectural project. Site and project are typically seen as distinct entities, with the former setting the way for the latter. Architecture is not made up of build ings or sites, but rather of their studied connection and a knowl edge that location is regarded as an architectural construct.2

1 Burns, Carol, “On Site: Architectural Preoccupations”, p.164.

2 Burns, Carol, “On Site: Architectural Preoccupations”, p.147.

1

1 2 Chapter 01 Rethinking the Way of Occupying

But the main issue for Heidegger3 is in this manner not in a specif ic architecture, buildings, machine, cycle, or asset, yet rather in the “challenging”: the manner in which the substance of innovation works on how we might interpret all matters and on the presence of those matters themselves — the all-unavoidable way we defy the mechanical world. Everything experienced mechanically is tak en advantage of for some specialized use. For example, individuals who get a stream by strolling over a basic extension could likewise appear to be utilizing the scaffold to challenge the waterway, mak ing it a part of perpetual chain of purpose. Yet, Heidegger contends that the extension as a matter of fact permits the waterway to act naturally, to remain inside its own stream and structure. On the other hand, a hydroelectric plant and its dams and designs change the waterway into only another component in an energy-delivering

3 Mark Blitz, “Understanding Heidegger on Technology,” The New Atlantis, Number 41, Winter 2014, pp. 63-80.

Figure

Figure

02|Aurel Stein, Roman bridge, Eski Mosul, with policeman on the right Figure 01| ear th bricks 3 4 Chapter 01 Rethinking the Way of Occupying

succession. Essentially, the customary exercises of workers don’t “challenge the farmland.” Instead, they safeguard the harvests, leaving them “to the discretion of the growing forces,” while “agricul ture is now a mechanized food industry.”

Present day machines are along these lines not only more evolved, or self-impelled, renditions of old devices like water or turning wheels. Innovation’s substance “has as of now from the start can celed that multitude of where the turning haggle factory recently stood.” Heidegger isn’t worried about the tricky inquiry of definitively dating the beginning of present day innovation, an inquiry that a figure significant to grasp it. Yet, he guarantees that well before the ascent of modern automation in the eighteenth hundred years, innovation’s quintessence was at that point set up. “It first of all lit up the region within which the invention of something like pow er-producing machines could at all be sought out and attempted.”

Figure

Figure

04|Ansel Adams Photographs

of National Parks

and

Monuments,

compiled 1941 - 1942 steel concrete metal

sheet glass

plastic reinforcement mega structure

Figure 03| 5 6 Chapter 01 Rethinking the Way of Occupying

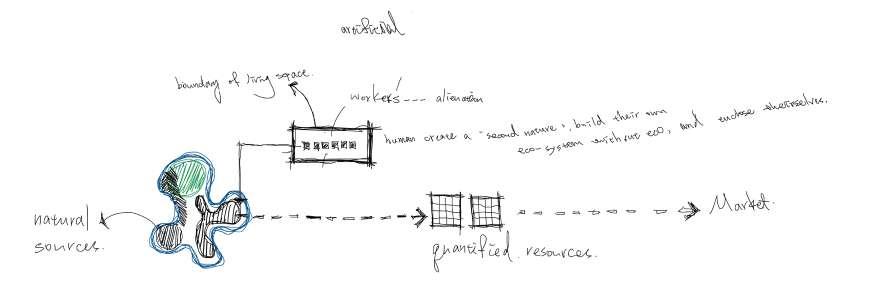

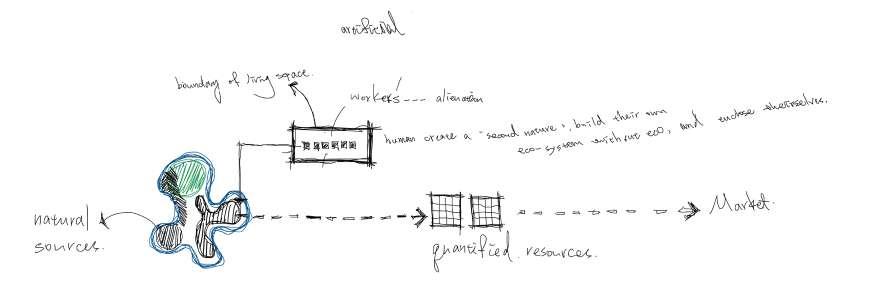

We can’t catch the embodiment of innovation by portraying the cosmetics of a machine, for “every construction of every machine already moves within the essential space of technology.” By this manner, an uranium mine presents how humanity ignores the re latioinship between nature, source, and human. What makes ura nium mine worse than a dam is it leaves scars on land with high toxic liquid to the land. Edith Hood said4 “They just came in, tore up the place, and left that contamination behind. And they really don’t want to do anything about it. They don’t care. The government doesn’t care. But we have connections with the land. We have stories of where we’re from. We still live here. We still call this place home.”

The major solution from EPA is to cover the contaminated land

4 voxdotcom. (2020, October 12). How the US poisoned Navajo Nation. You Tube. Retrieved July 21, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ET Pogv1zq08&t=563s&ab_channel=Vox

mining wasteuranium

Figure

mining wasteuranium

Figure

06|Uranium mining in Namibia Figure 05| 7 8 Chapter 01 Rethinking the Way of Occupying

by moving soil from somewhere else and covering it. That’s it. For example, a mine called Northeast Church Rock Mine 305 in New Mexico, was buried, meaning they just did remediation by covering new soil to the mine.5 In long term, it is probably an easy way to do so. It means it may be cleaned by the natural process after 500 years later. The contamination could be transformed into some thing harmless. But in short term, within decades, the local people will have been suffering from this condition.

And, again, I think it’s also about the way we occupy the land. If we just bury the mine, it’s like the way a huge dam treats a river. It’s like cut out its life. Abandoned mines have died. The point is how do we treat the dead mines properly? I think its more about the land justice.

This project converts the mining process. It has the similar manner 5 EPA, Navajo Nation: Cleaning Up Abandoned Uranium Mines, 2022

to the bridge that “borrow“ the contamination from mines and mix it with biochar which has capability to bind toxic and create a new material lifecycle for contamination.

bindingcontamination

bindingcontamination

Figure 07|

Project Statement Diagram

contamination +

biochar reinvented biochar units

9 10 Chapter 01 Rethinking the Way of Occupying

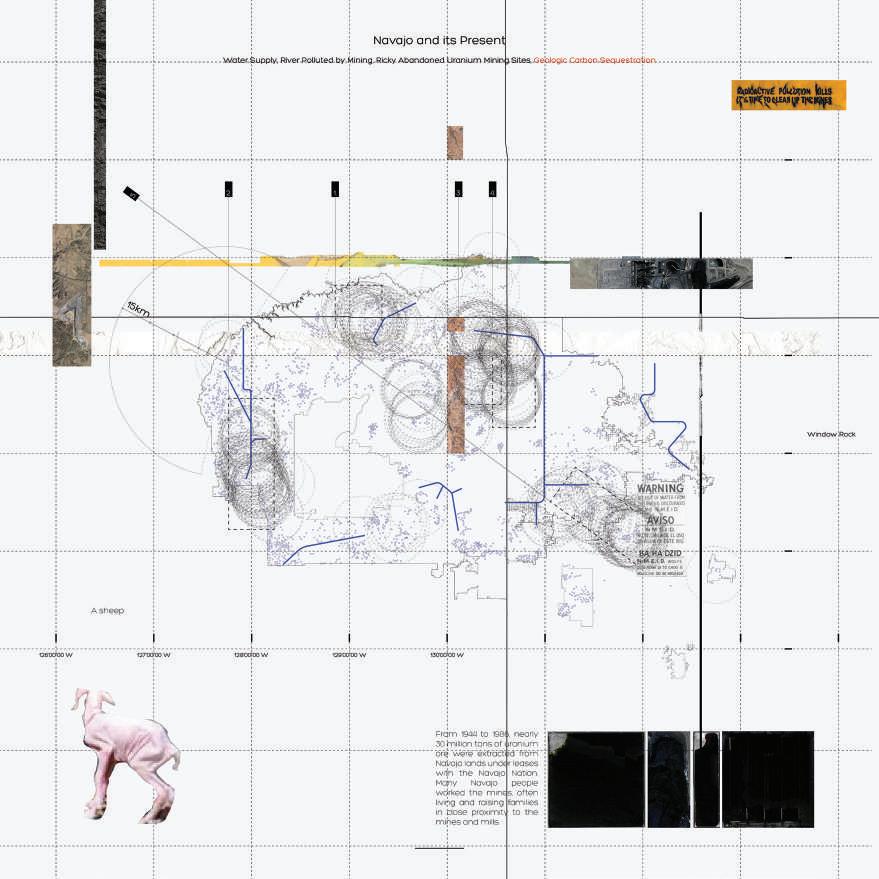

1-2_Scratches on Mother Nature

The Navajo Nation is home to more than 500 abandoned uranium mines, which has been identified as major environmental issue within the Navajo. Previous health studies have articulated numer ous human health hazards, including infants’ neurodevelopment and cancer, associated with AUMs and multiple environmental mechanisms/pathways (e.g., air, water, and soil) for contaminant transport.1 Back in the history, the Navajo has been unfairly treated as minority. The traditional Navajo homeland extends from Arizona to western New Mexico, where the Navajo lived, cultivated crops, and kept cattle. In the Southwest, there was a long history of tribes , attacking and trading with one another, with treaties being signed

1 Yan Lin et al., “Environmental Risk Mapping of Potential Abandoned Uranium Mine Contamination on the Navajo Nation, USA, Using a GIS-Based Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Approach,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 27, no. 24 (2020): pp. 30542-30557, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-09257-3.

Figure

08|Uranium mining in Navajo 11 12 Chapter 01 Rethinking the Way of Occupying

and broken. Interactions between Navajo, Spanish, Mexican, Pueblos, Apache, Comanche, Ute, and subsequently European Americans were covered. Individuals and Native Ameri cans may be victims of these wars, as well as perpetrators of violence to further their own goals. The Long Walk of the Navajo, also known as the Long Walk to Bosque Redondo (Navajo: Hwéeldi), was the United States federal gov ernment’s deportation and attempted ethnic cleansing of the Navajo people in 1864. The Navajos were compelled to walk from what is now Arizona to eastern New Mexico. Between August 1864 and the end of 1866, there were 53 separate forced marches. According to some

Carrier Dome, Syracuse University 1751581 59 1651 66 306 1641 67 1691 70 1881871 89 190 1921911 93 194 294 541501 291 1741731 76 177 1831 84 228222 223 224 225 226 227 394393 291 244 245 246 247 305 Figure 09|Uranium mines in Navajo source: Abandoned Mines Cleanup: Site Screen Reports, EPA, 1998-2009 13 14 Chapter 01 Rethinking the Way of Occupying

anthropologists, the “collective trauma of the Long Walk...is import ant to modern Navajos’ sense of peoplehood.”2

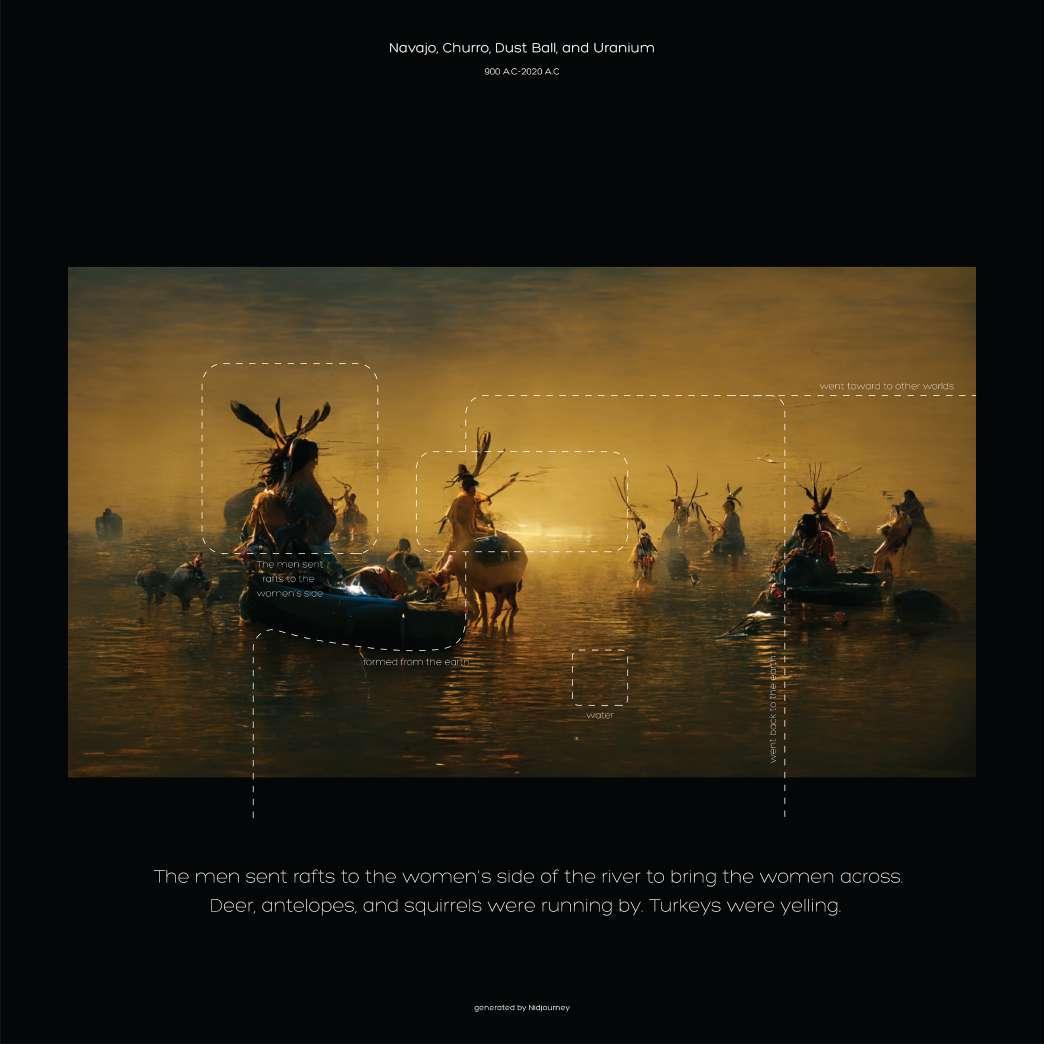

The activities of uranium mining ignored the context of local cul ture. It had been top-down actions for decades, driven by tech nology and capital. Between 1944 and 1986, mining corporations extracted 4 million tons of uranium from Navajo land. The ore was acquired by the federal government in order to manufacture nucle ar bombs. As the Cold War danger faded, the firms departed, aban doning over 500 mines.

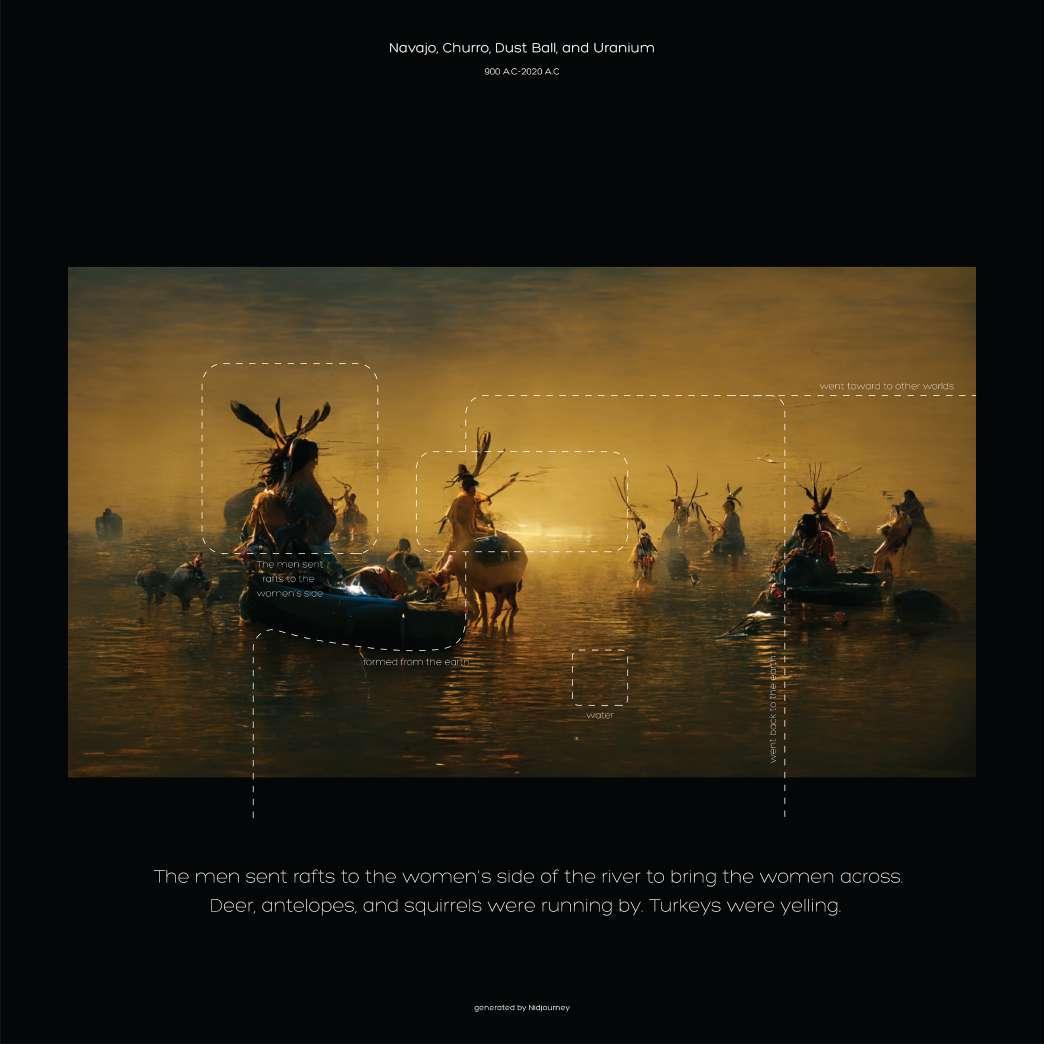

On the contrary, the Navajo has its own mythology which peaceful ly describes the ways how Navajo people live with “mother nature“ in harmony. As a Navajo says, “The reason for counting is like you

2 My Father’s Torture, 2012. Mural painting by Shonto Begay, Courtesy of Fort Sumner Historic Site/Bosque Redondo Memorial

Third World

known as the Yellow world

Navajo

Figure 10|The

(also

in

Mythology) 15 16 Chapter 01 Rethinking the Way of Occupying

get kind of greedy and you want more instead it just vice versa you start counting, Mother Nature starts deducting.” They set their heart on being hózhoǫ́3 with mother nature. This mindset is rooted from their mythology, called Dine’ Bahane, which narrates that the Na vajo came from The Four Worlds, where is described as a peaceful universe with different animals, people, and matters. The way they interact with the land and the Nature has been light and gentle.

3 In “Navajo-English Dictionary” (1958). Navajo - English Dictionary, written by Wall, Leon and Morgan, William, hózhoǫ́ means very; extremely; well; very much. In general context, hózhoǫ́ is hard to be translated into english. To Navajo, according to Wayne Peate, M.D, it is “A complex Navajo philosophical, religious, and aesthetic, roughly translated to “beauty.” Hozho also means seeking and incorporating aesthetic qualities into life, it means inner life and har mony, and it means making the most of all that surrounds us. It refers to a positive, beautiful, harmonious, happy environment that must be constantly created by thought and deed. Hozho encourages us to go in beauty and to enjoy the gifts of life and nature and health. “

17 18 Chapter 01 Rethinking the Way of Occupying

Contamination in Uranium Mine and its Current Remediation

2-1_Goal of 1%: Environmental impacts of uranium mining

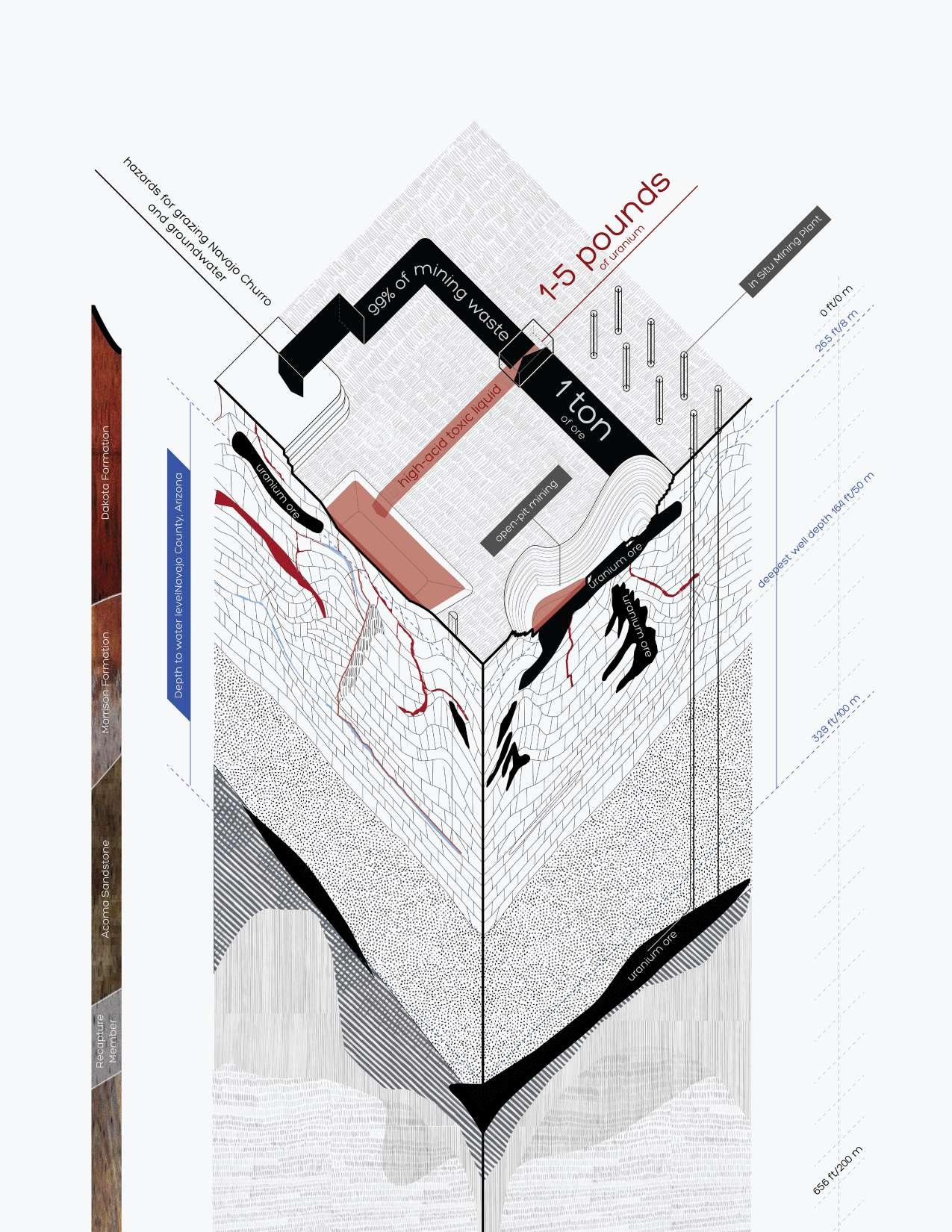

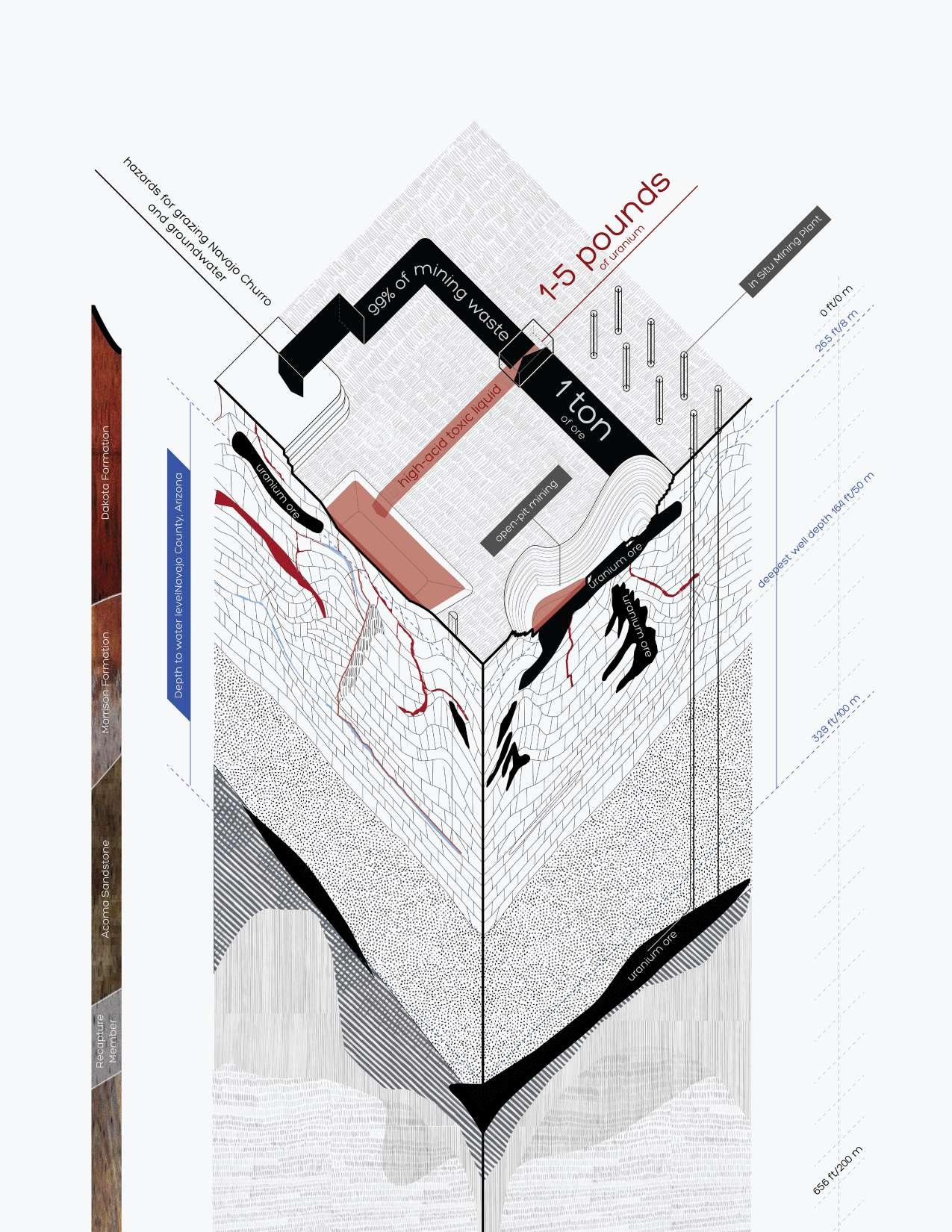

Tailings of uranium mining activities are often disposed of in near by impoundments. These tailings pose significant environmental and health problems related to emissions, windblown dust, and chemical leaching into water, including heavy metals and arsenic.

Specifically, raw ore is hauled to the top and crushed into fine sand. The rich uranium-bearing minerals are subsequently extracted us ing heap leaching with acids or bases, and the residual radioactive sludge, known as “uranium tailings,” which may maintain up to 85% original radioactivity of the raw ore2 is held in massive impound

1 C. Arnold, “Once Upon a Mine: The Legacy of Uranium on the Navajo Nation,” Environ. Health Perspect. 122, A44 (2014).

2 Robinson, Paul; Hector, Alice; Luis, Judy; Benavides, David; Hancock, Don (1979), “Ura nium Mining and Milling: A Primer” (PDF), The Workbook, Albuquerque, New Mexico: South west Research & Information Center, 4 (6–7), archived from the original (PDF) on July 8, 2010, retrieved December 9, 2012.

2

19 20 Chapter 02 Contamination in Uranium Mine and its Current Remediation

ments. Depending on the uranium composition of the material, a short ton (907 kilograms) of ore only yeilds 1-5 pounds (0.45 to 2.3 kg) of uranium.3

Typically, many governments throughout the world have politicized these hazards because they disproportionately impact low-income and minority communities.4 Although the Navajo were eventually able to prohibit mining on their territory, same issues persist in oth er communities today and should not be neglected when discuss ing the future of Uranium mines.

3 Grammer, Elisa J. (1981), “The Uranium Mill Tailings Radiation Control Act of 1978 and NRC’s Agreement State Program”, Natural Resources Lawyer, 13 (3): 469–522, JSTOR 40922651

4 B. Weil, “Uranium Mining and Extraction from Ore,” Physics 241, Stanford University, Winter 2012.

Figure 11|Goal of 1% of ore 21 22 Chapter 02 Contamination in Uranium Mine and its Current Remediation

2-2_Current Remediations of Abandoned Uranium Mine

a. Improving Subsurface Uranium Cleanup Methods

A group of scientists revealed chemical mechanisms that convert hexavalent uranium [U(VI)] to more insoluble forms of tetravalent uranium [U(IV)] in subterranean sediments at a uranium contami nation site. This information might result in more efficient cleanup methods by permitting remediation designers to enhance the conversion from soluble U(VI) to more insoluble U(IV) forms, that include the mineral uraninite (UO2). The aim of such remediation is to either anchor (stop uranium plumes from migrating lower) or immobilize the uranium in the groundwater material. Before scien tists outlined the current findings, the chemical mechanisms and mineralogic endpoints of U(VI) in natural sediments had not been completely documented.

1 Bargar, J.R., Williams, K.H., Campbell, K.M., Long, P.E., Stubbs, J.E., Suvorova, E.I., Le

zama-Pacheco, J.S., Alessi, D.S., Stylo, M., Webb, S.M., Davis, J.A., Giammar, D.E., Blue, L.Y., and Bernier-Latmani, R., 2013, Uranium redox transition pathways in acetate-amended sedi ments: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, v. 110, no. 12, p. 4506-4511, doi:10.1073/ pnas.1219198110.

Figure 12|A former uranium mill tailings site near Rifle, Colorado, is next to the Colorado River. Photo credit: John Bargar, SLAC National Accelerator Lab oratory.

23 24 Chapter 02 Contamination in Uranium Mine and its Current Remediation

b. Biochar potential for abandoned uranium mine land restoration

Biochar, which is made from woody biomass that would otherwise be burnt in slash piles, may be applied to soil to enhance soil char acteristics, and is one approach for restoring AML soil productive po tential. It also has the ability to enhance water quality, bind heavy metals, and reduce harmful chemical concentrations, all while increasing soil health and establishing sustainable plant cover, minimizing soil erosion, leaching, and other unexpected, negative environmental repercussions. In test plots at the Hope Mine in As pen, Colorado, researchers are evaluating the efficiency of biochar amendment in restoring soil impacted by mine waste rock heaps. In addition to biochar, the applied supplement included a seed mix,

1 Rodriguez-Franco, C., Page-Dumroese, D.S. Woody biochar potential for abandoned mine land restoration in the U.S.: a review. Biochar 3, 7–22 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42773020-00074-y.

compost, hydromulch, and naturally occurring mycorrhizal fungus to aid plant root nutrition uptake. To keep the amendment in place, biodegradable netting was installed on the ground surfaces of each plot. Plant re-establishment, which took place within a year, required no watering.2

2 EPA (Environmental Protection Agency), accessed July 31, 2022, https://www.epa. gov/remedytech/green-remediation-best-management-practices-mining-sites.

Figure

Figure

13|

Hope Mine Biochar Project by Erin Rasmussen, 2012

25 26 Chapter 02 Contamination in Uranium Mine and its Current Remediation

c. Northeast Church Rock Mine Remediation

According to Evironmental Protection Agency (EPA), from 1967 until 1982, NECR was run by the United Nuclear Corporation (UNC). They extracted nearly 3.5 million tons of ore in total during this period, making this the Navajo Nation’s second most productive mine. EPA, oversaw multiple time-critical activities in which UNC removed about 200,000 tons of contaminated soil to address pollution that had migrated off the NECR Mine Site into the nearby residential area. This dirt was returned to the mine site pile, which was regrad ed, covered, and vegetated in order to stabilize the contamination. During development, the EPA provides optional alternate housing for surrounding households. The NECR remediation plan calls for

1 EPA. Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.epa. gov/navajo-nation-uranium-cleanup/northeast-church-rock-mine.

the relocation of about 1.4 million tons of contaminated soil to the neighboring UNC Mill Site. This construction operation, which in cludes the building of a repository or holding cell at the UNC/GE Site, necessitates extensive planning throughout the project’s design phase.

Figure 14|EPA_ Overlooking the NECR Mine facing Northeast, 2018

27 28 Chapter 02 Contamination in Uranium Mine and its Current Remediation

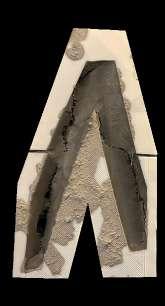

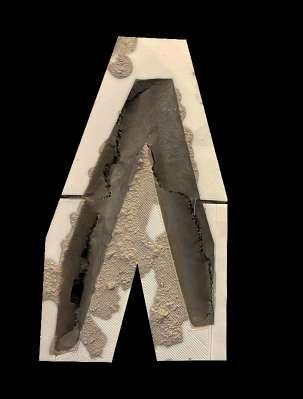

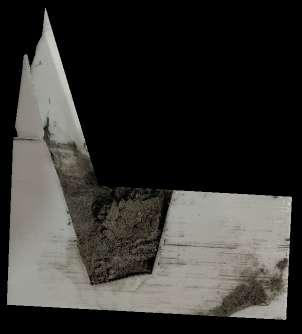

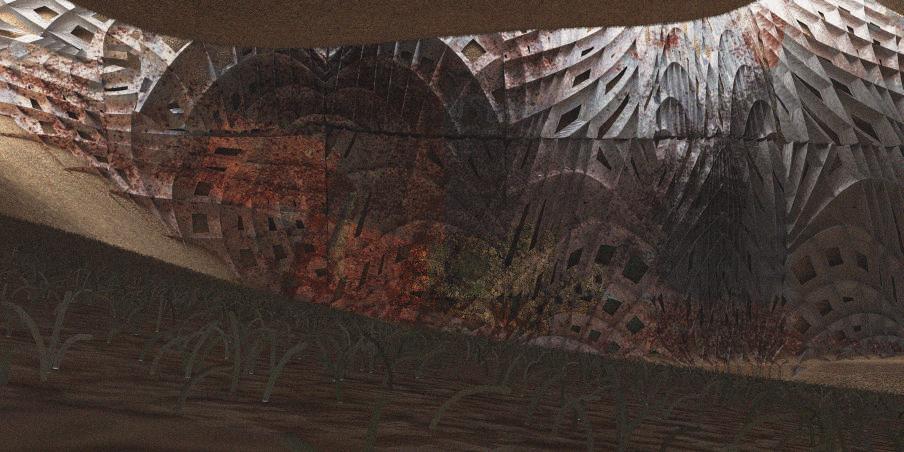

2-3_Re-excavate the Contamination to Mix with Biochar

The goal of this thesis project excavates the contamination out from earth and mix it with biochar to regenarate a new material, which binds the contamination. There are three spots can operate this action, including the open-pit mine, the tailing, and the mining waste hill. As described in the first chapter, the process of building a bridge “borrowes“ dust from earth to make bricks. Eventually the bridge will become the dust once again, recycling back to earth. The approach of this project shares a same concept that brings a part of dust and contamination together, mixed with biochar to reinvent a new material, which sooner or later will be decaying and going back to nature.

contamination + biochar reinvented biochar units

bindingcontaminationbindingcontamination Figure 16|re-excavate the contamination Figure 15|re-excavate the contamination 29 30 Chapter 02 Contamination in Uranium Mine and its Current Remediation

The process of making new material is also eco-friendly. Firstly, the stability of biochar dives in the concept of carbon capture, called pyrogenic carbon capture and storage (PyCCS) , which has been introduced by Werner in 2018.2 Secondly, biochar is also a material that can improve the soil texture that provides good earth condi tion for grass to grow, which is desirable for grazing livestock, such as Navajo Churro.

1 Constanze Werner, Hans-Peter Schmidt, Dieter Gerten, Wolfgang Lucht und Claudia Kammann (2018). Biogeochemical potential of biomass pyrolysis systems for limiting global warming to 1.5 °C. Environmental Research Letters, 13(4), 044036. doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aab b0e

2 Constanze Werner et al. (2018): Biogeochemical potential of biomass pyrolysis systems for limiting global warming to 1.5° C. Environmental Research Letters, 13(4), 044036. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aabb0e

Figure 17|a new material lifecycle 31 32 Chapter 02 Contamination in Uranium Mine and its Current Remediation

Precedents

4-1_New Notions of occupying

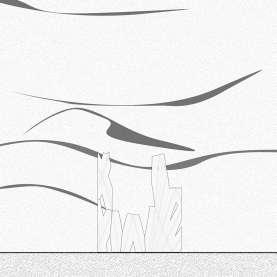

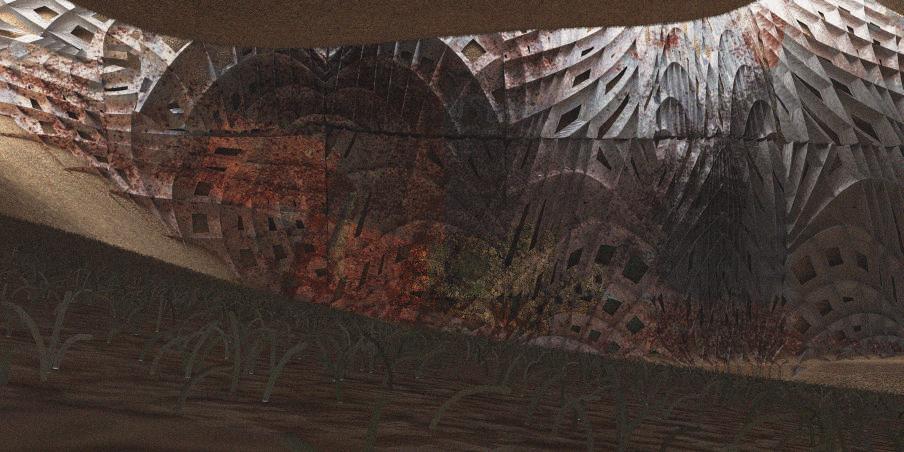

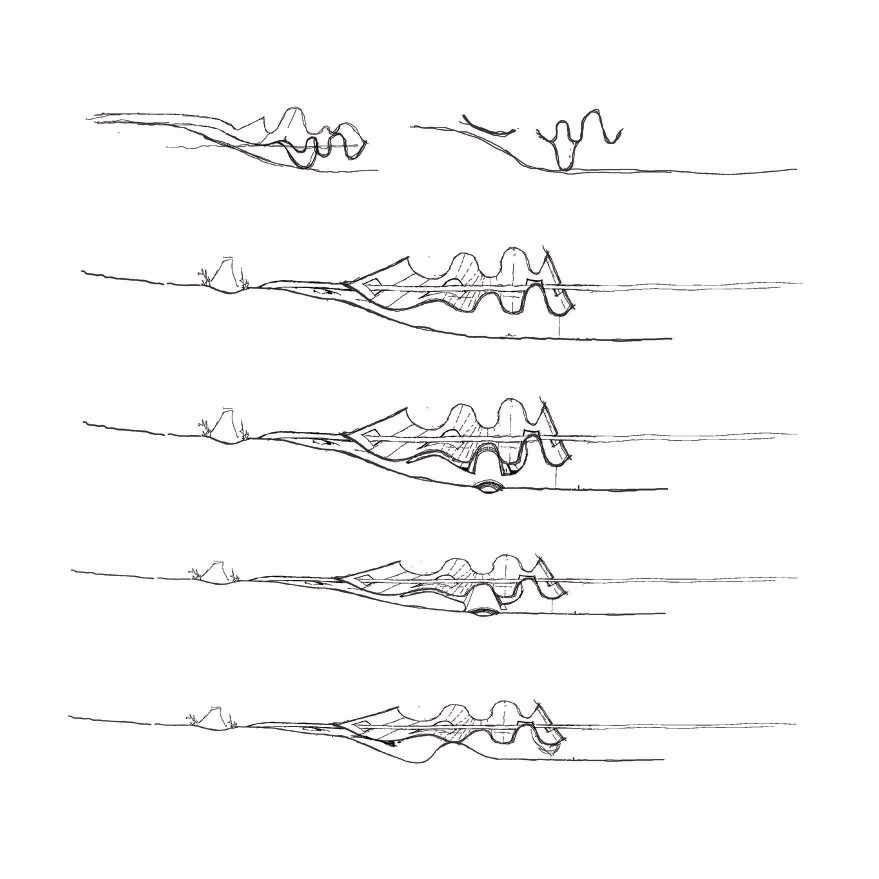

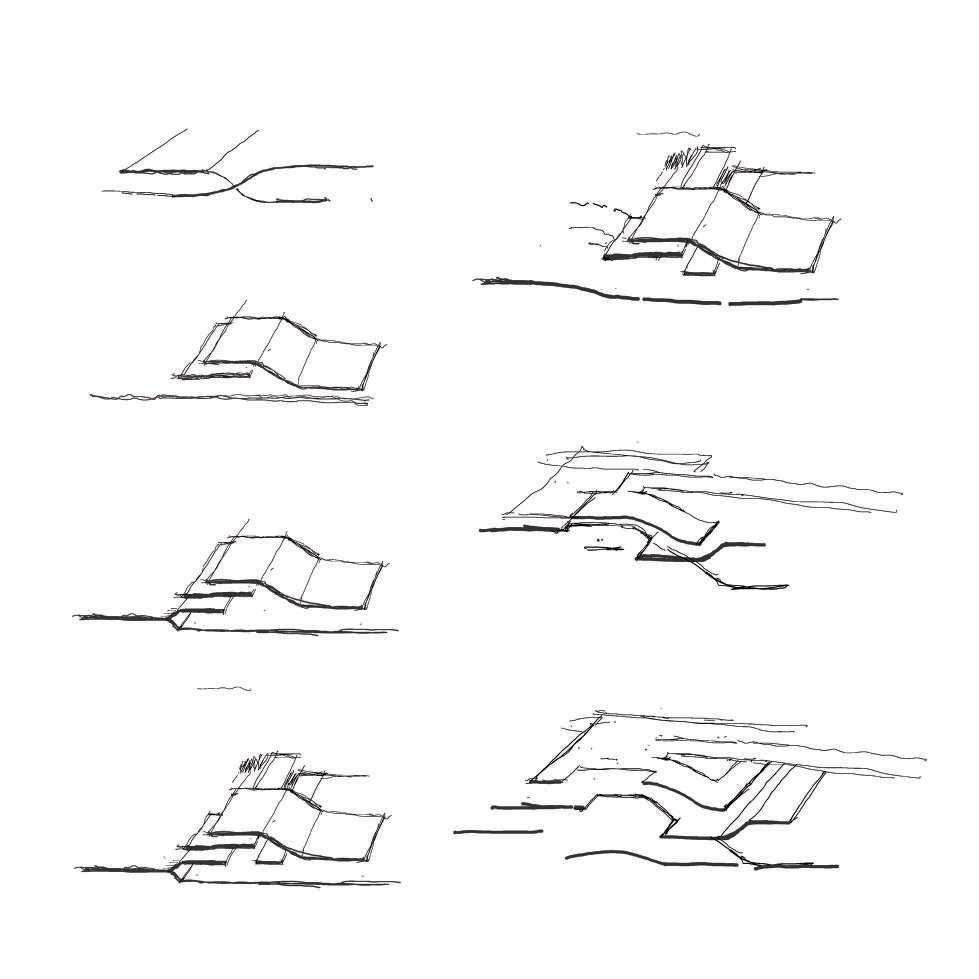

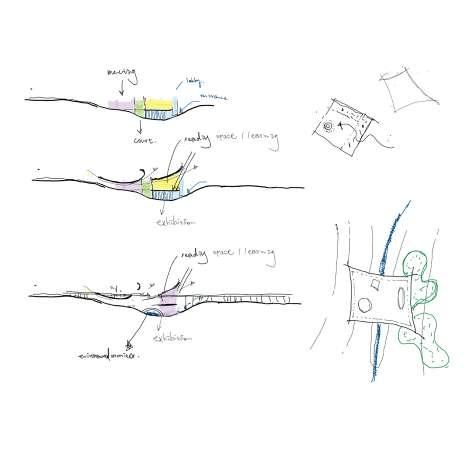

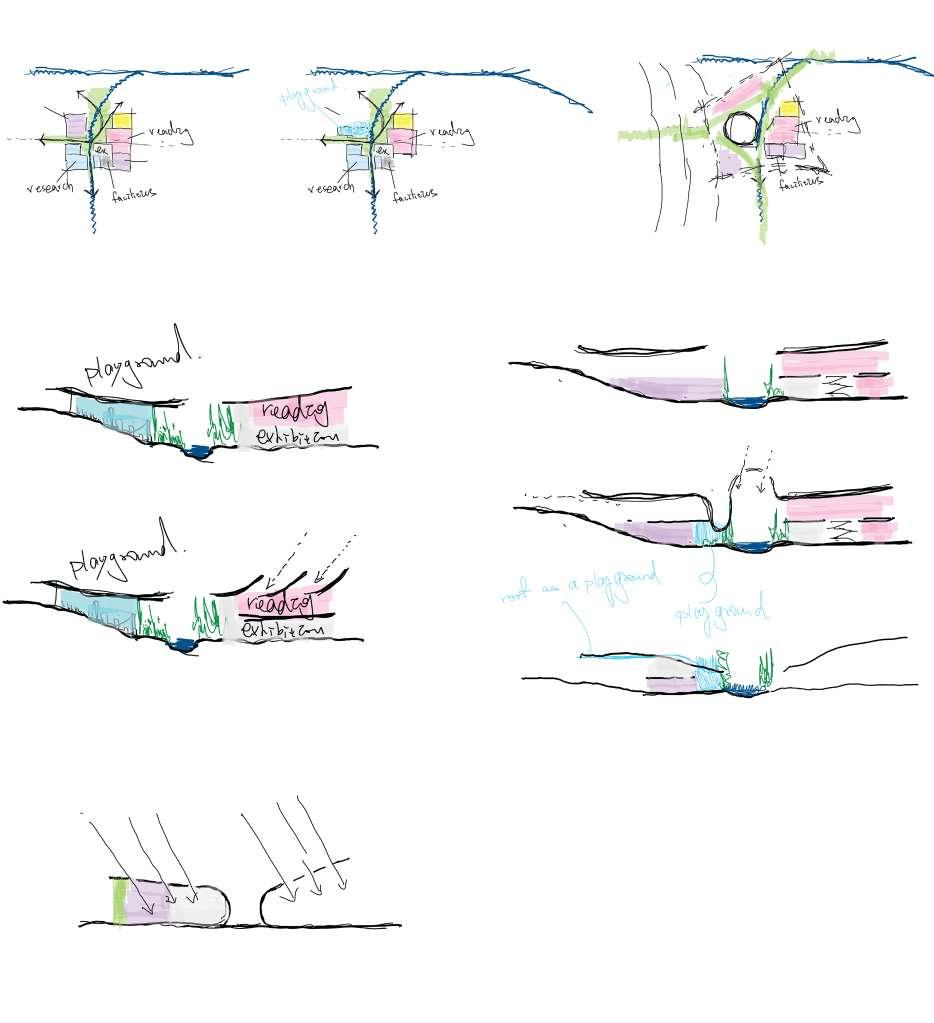

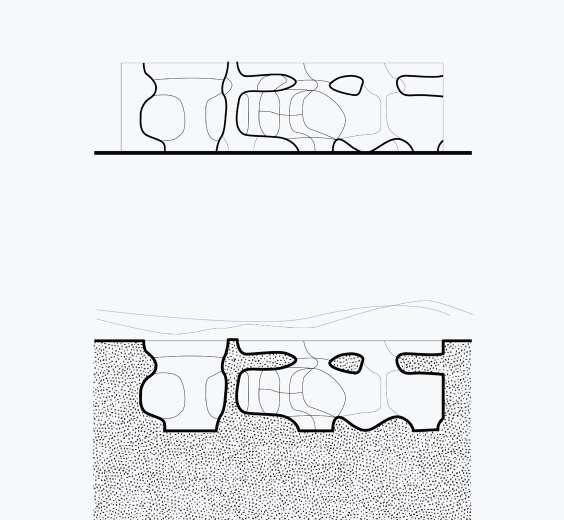

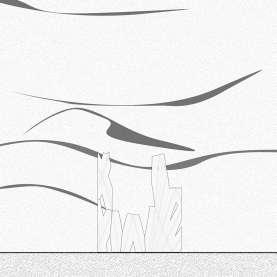

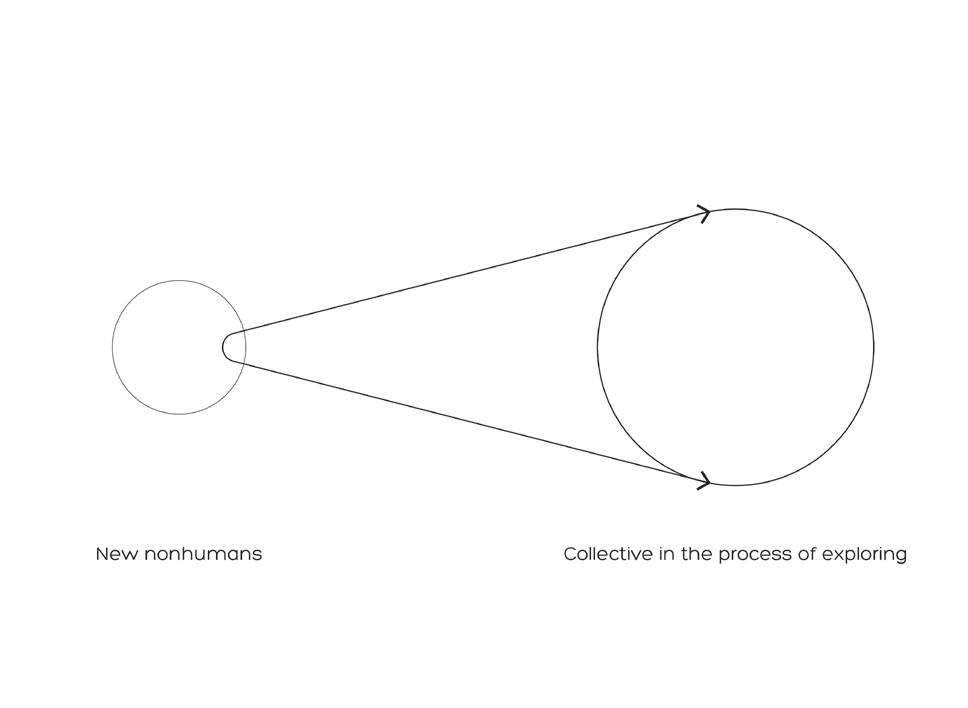

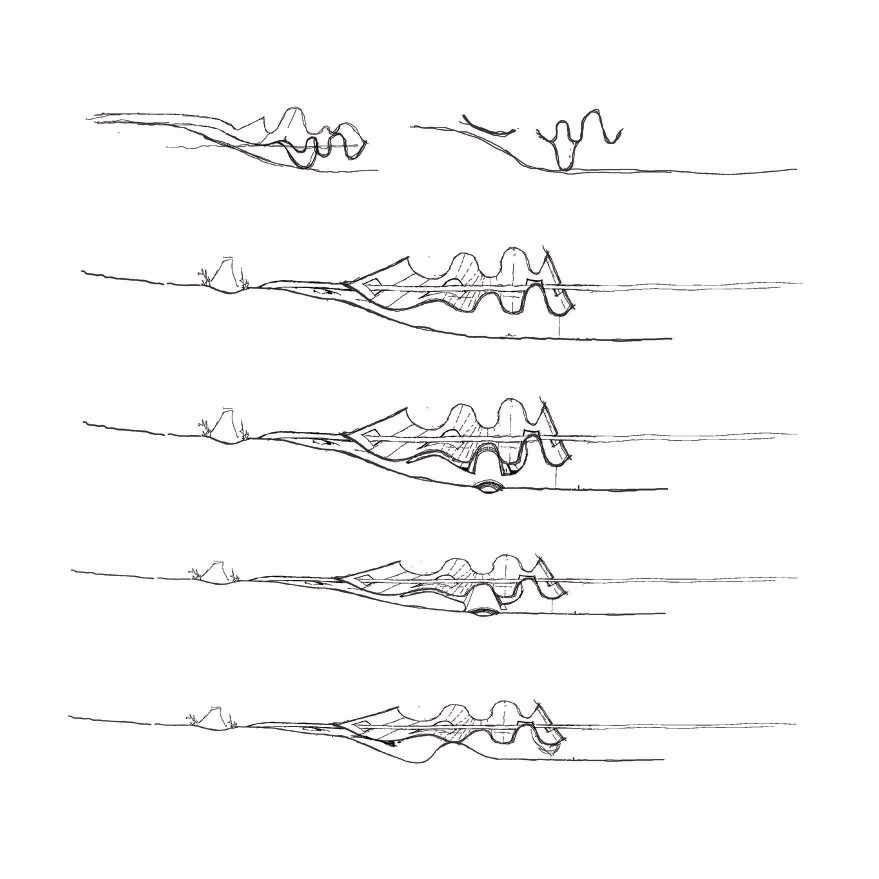

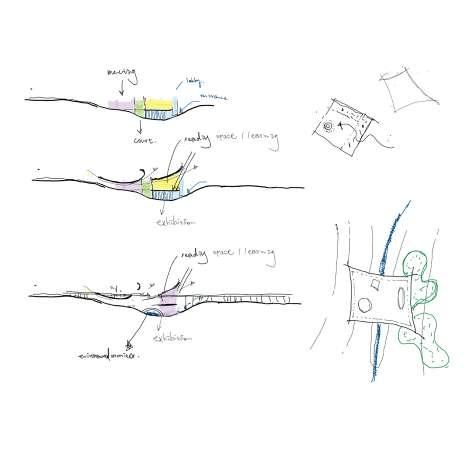

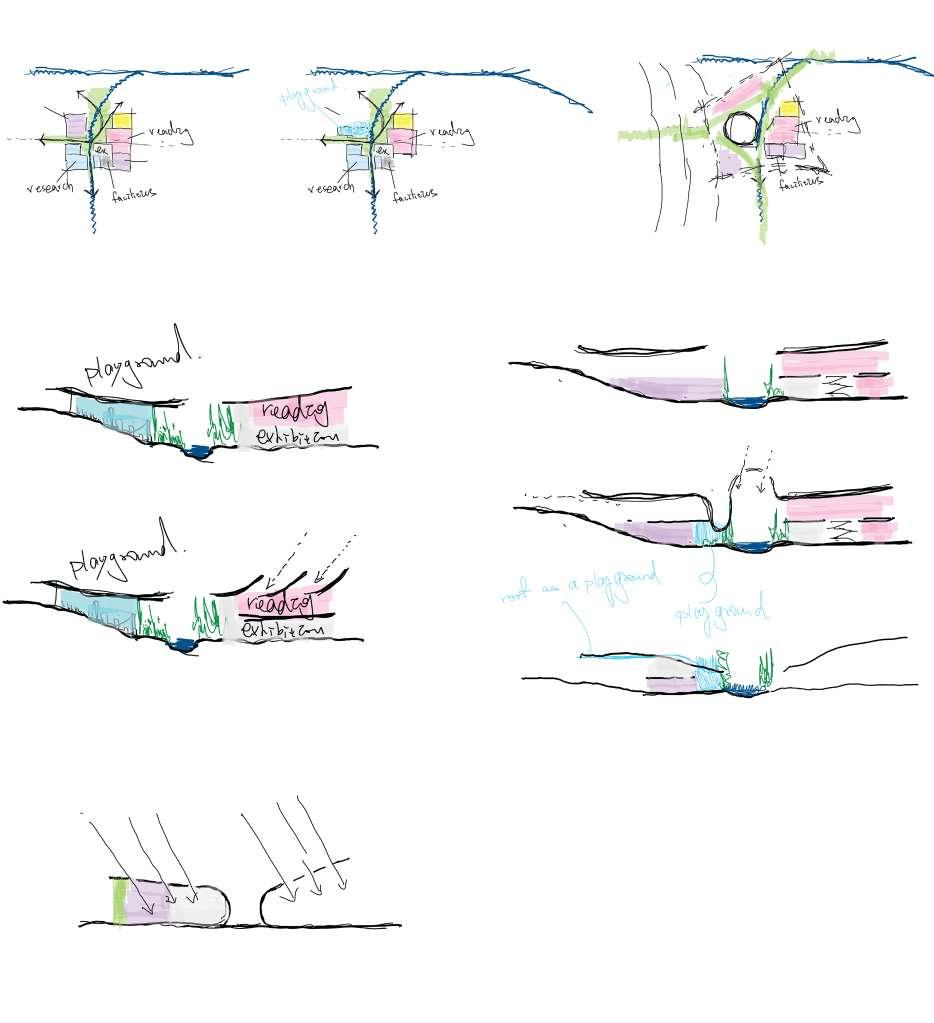

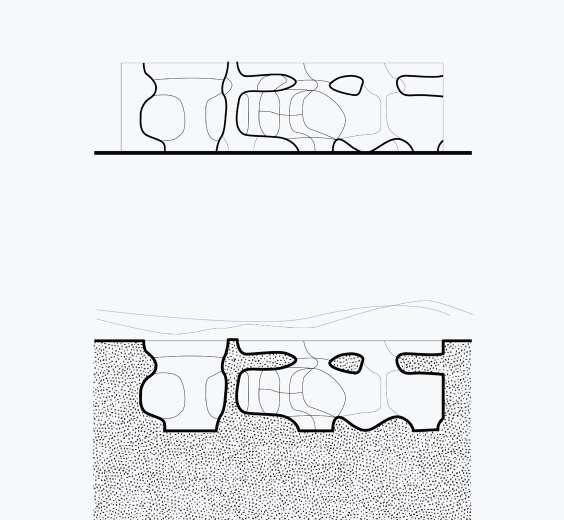

This chapter looks for precedents that are not directly related to the biochar but are inspirations of it. The first section looks for prece dents, such as Taichung Opera Theater and Louisiana State Muse um, which are inspired by the form of cave or earth. Interestingly, when the groundlines of both start from their roof level, meaning the interface start to encounter the earth. That is the moment that is inspiring to this project when the earth need to be excavated.

The second section looks for some projects that focus on biochar production and material testing of it. Technically, biochar is made of feedstock, which is the reason why it is porous and light. On one hand, it can be mixed with cement, clay, concrete, and earth. On the other, it is capable to absorb more water than a brick with the some size.

3

33 34 Chapter 03 Precedents

a. Taichung Opera Theater

Trahan Architects

State Museum

Both Taichung Opera Theater and Louisiana State Museum create places with sence of cave. Both of them take some natural elements to interior, integrating them into themselves. To this research design project, it is de sirable to see what if the ground level flip upon the roofs.

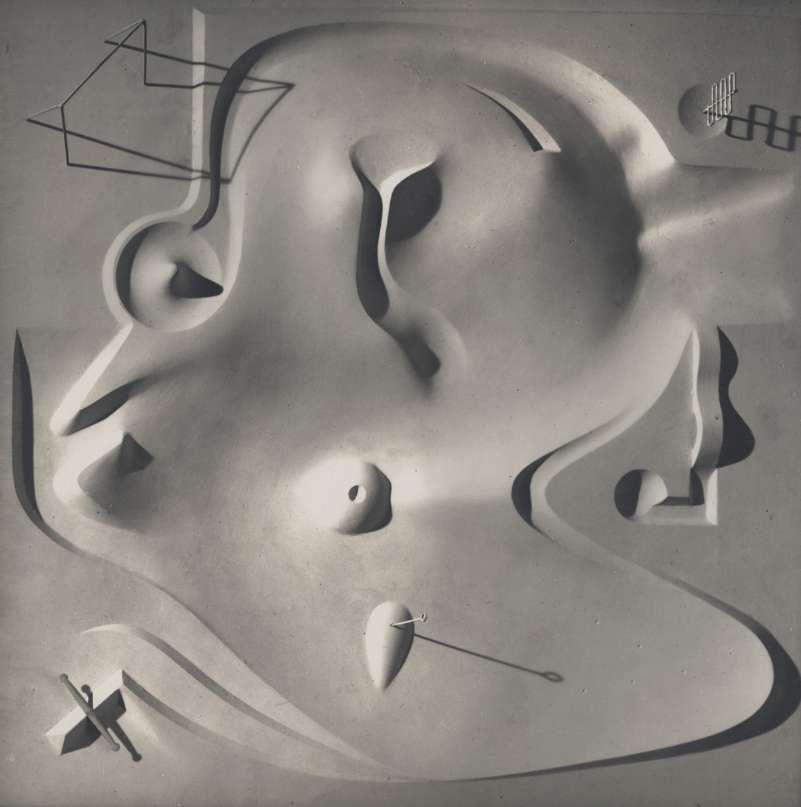

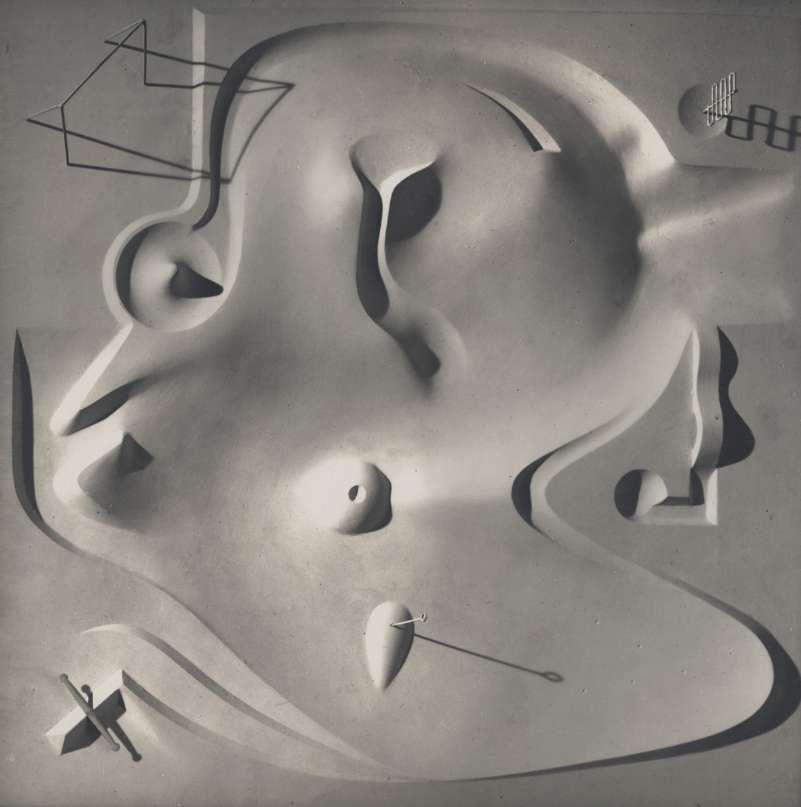

c. Isamu Noguchi Contoured Playground

The landscape that is created by Isamu Noguchi is always formed with earth. Contoured Playground is a paradigm, which people ex perience the space through smooth and gentle topography.

b.

Louisiana

Figure 20|Contoured PlaygroundFigure 18|Taichung Opera Theater Figure 19|Louisiana State Museum 35 36 Chapter 03 Precedents

3-2_Different techniques to build with biochar

Dutch scientist Wim Sombroek discovered upon a black soil with outstanding nutritional qualities while exploring Brazil’s Amazon basin in the 1960s. This soil had high concentrations of phospho rus, nitrogen, potassium, and plant matter, as well as significant concentrations of black carbon. The material is referred to as Terra Preta, or black earth, in Portuguese. It is also a powerful carbon sink and can sequester the element for at least a thousand years.

Essentially, bichar is a natural material in ancient time which might even be a critical material that enriched the whole development of civilization in the Amazon with numerous and complex societies.2

On one hand, biochar is not a high-end techology material. On the

1 W. I. Woods, Amazonian Dark Earths Wim Sombroek’s Vision (Springer, 2009), 477.

2 W. I. Woods, Amazonian Dark Earths Wim Sombroek’s Vision (Springer, 2009), 473.

other hand, it contributes to carbon reduction, heavy metal con tamination, and reduction of soil acidity3 4

Raw Materials of Biochar

Biochar can be made from various biomass feedstocks: wood5

3 Rodriguez-Franco, C., Page-Dumroese, D.S. Woody biochar potential for abandoned mine land restoration in the U.S.: a review. Biochar 3, 7–22 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42773020-00074-y

4 According to Carlos Rodriguez-Franco and Deborah S. Page-Dumroese, Using this ‘waste’ biomass for biochar and reclamation operations reduces the danger of wildfires, air pollution from burning, and particles emitted from burning wood. Biochar has the ability to enhance water quality, bind heavy metals, and reduce harmful chemical concentrations, all while increasing soil health and establishing sustainable plant cover, minimizing soil erosion, leaching, and other unexpected, negative environmental repercussions.

5 S. Gupta, H.W. Kua, H.J. Koh, Application of biochar from food and wood waste as

37 38 Chapter 03 Precedents

waste products from agriculture such as rice husk6 oil palm waste7 , straw8, or from wastewater sludge9 Also, there are various tech niques of biochar production, namely: slow and fast pyrolysis10 gas ification11 or torrefaction12

green admixture for cement mortar, Sci. Total Environ., 619–620 (2018), pp. 419-435

6 A. Mohammadi, A.L. Cowie, T.L. Anh Mai, M. Brandão, R. Anaya de la Rosa, P. Kristian sen, S. Joseph Climate-change and health effects of using rice husk for biochar-compost: comparing three pyrolysis systems, J. Clean. Prod., 162 (2017), pp. 260-272

7 S. Robb, P. Dargusch, A financial analysis and life-cycle carbon emissions assess ment of oil palm waste biochar exports from Indonesia for use in Australian broad-acre agriculture, Carbon Manag., 9 (2) (2018), pp. 105-114

8 Close T. Mattila, J. Grönroos, J. Judl, M.R. Korhonen, Is biochar or straw-bale construc tion a better carbon storage from a life cycle perspective? Process Saf. Environ. Protect., 90 (6) (2012), pp. 452-458

9 Z. Liu, S. Singer, Y. Tong, L. Kimbell, E. Anderson, M. Hughes, D. Zitomer, P. McNamara, Characteristics and applications of biochars derived from wastewater solids, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., 90 (2018), pp. 650-664

10 Y. Wang, R. Yin, R. Liu, Characterization of biochar from fast pyrolysis and its effect on chemical properties of the tea garden soil, J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol., 110 (1) (2014), pp. 375-381

11 Z. Zhang, Z. Zhu, B. Shen, L. Liu, Insights into biochar and hydrochar production and applications: a review, Energy, 171 (2019), pp. 581-598

12 Q.V. Bach, W.H. Chen, Y.S. Chu, Ø. Skreiberg, Predictions of biochar yield and elemen

Figure 24|sludge Figure 21|wood Figure 22|rice husk Figure 23|straw 39 40 Chapter 03 Precedents

a. Biochar brick is the most common technique, which makes the brick lighter. When using cement and lime, sand can be comletely replaced by biochar reducing the weight of the materail by factor

513 Biochar has been successfully used as an alternative to various cement-based composites, providing additional properties such as insulation, passive cooling, and light weight.14

b. Biochar roof tile was tested as a prototype in the 4 Wall Projects, which helped people of El Sauce, Nicaragua acuire homes.

c. biochar tiles

d. biochar plaster

tal composition during torrefaction of forest residues, Bioresour. Technol., 215 (2016), pp. 239-246

13 Hans-Peter Schmidt, Ithaca Institute for carbon strategies, 2013

14 “Cast in Carbon,” IAAC Blog, Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia, https:// www.iaacblog.com/programs/cast-in-carbon/.

Figure

Figure

25|

biochar

bricks

Figure

26|

biochar tile

Figure

27|biochar tiles 41 42 Chapter 03 Precedents

Design and Fabrication

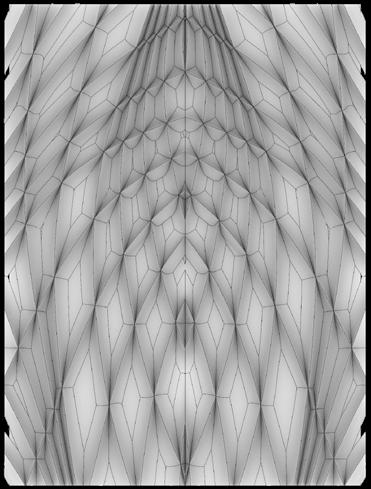

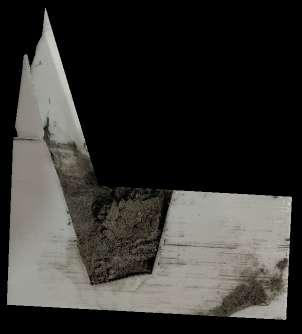

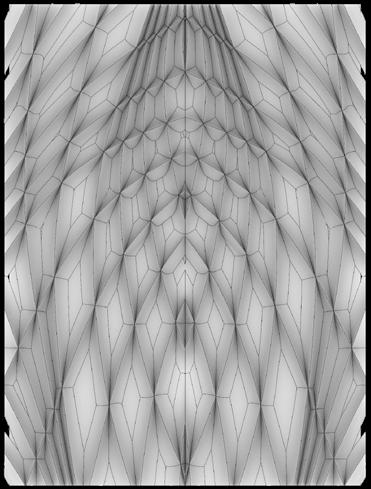

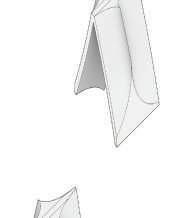

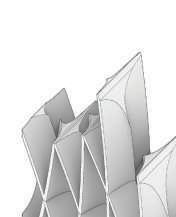

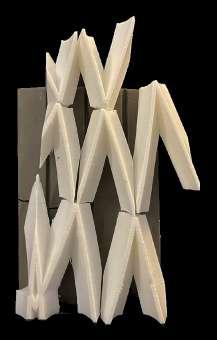

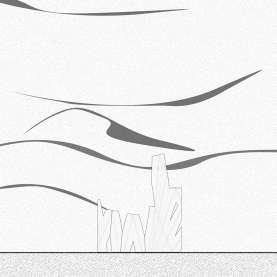

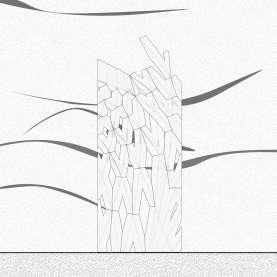

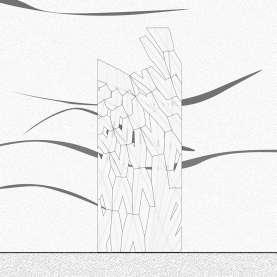

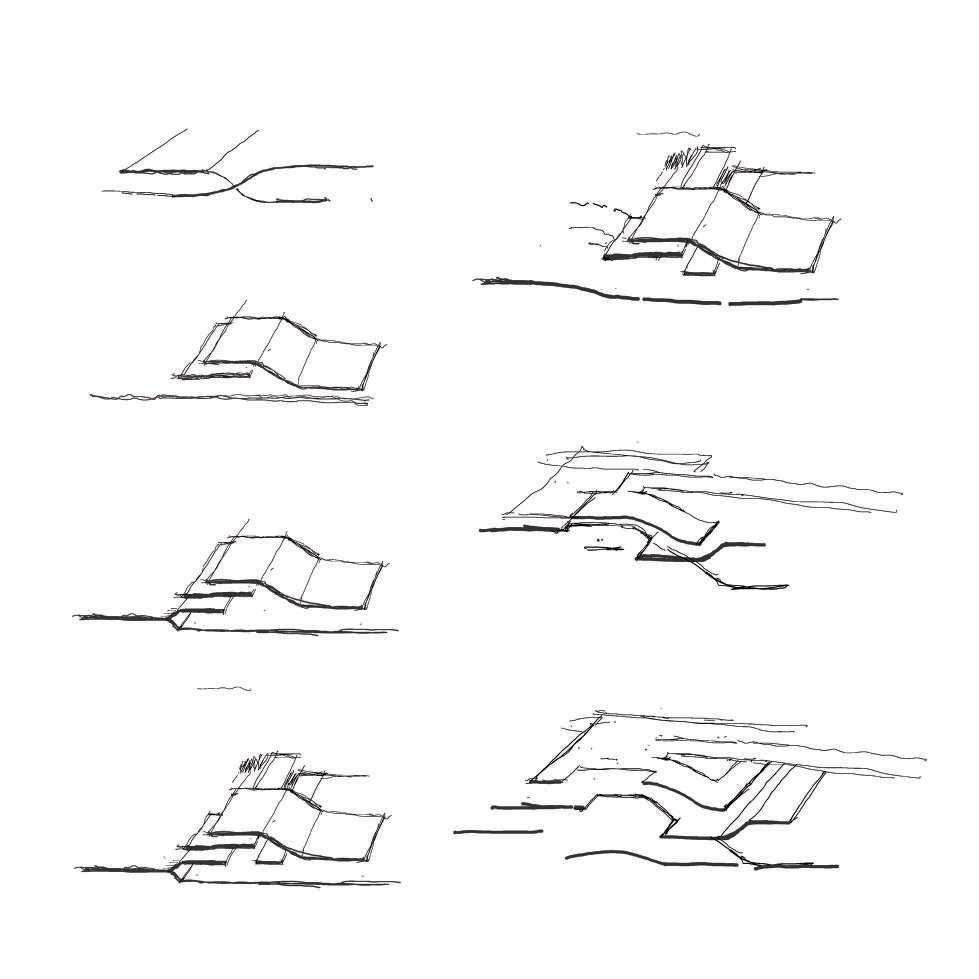

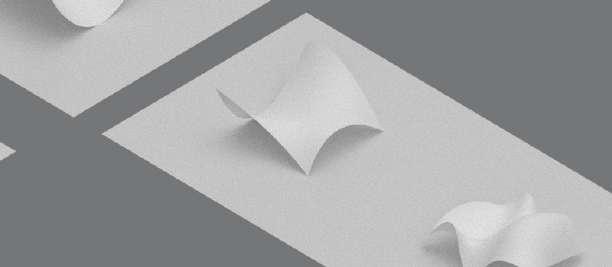

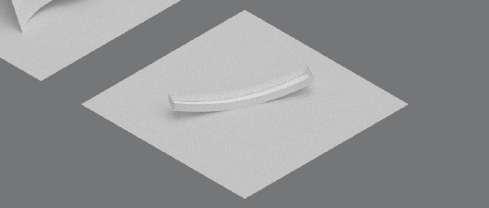

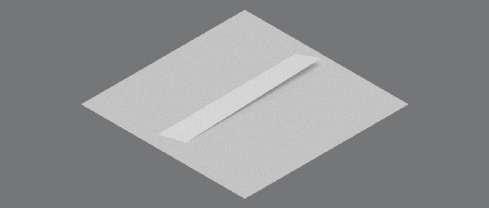

4-1_Formal exploration of biochar

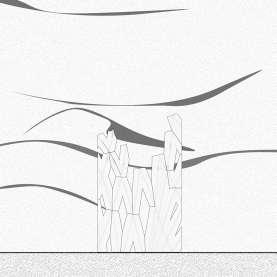

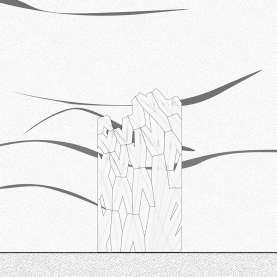

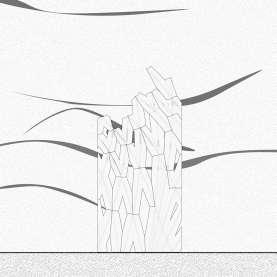

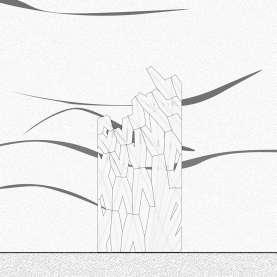

This chapter will be exploring the formal expression of biochar. The form of the space that is built by biochar is inspired by the prece dents study. There raises a question: What if we see the volume of a building in an opposite way? To be more specific, the contam ination is occurring underground level so how it is involved and encountered by new invented material, which is made of biochar, is significant. This project studies the form of biochar through different ways. Firstly, it starts with precedent studies in section. Secondly, it goes through different sections to show the similar experience of the precedents. Furthermore, it converts that experience in the sections into physical works that are made by clay and other ma terials, showing the interface between space, human, volume, and nature. Finally, it will be focusing on the biochar unit testing, which is needed to be employed through out the spatial exploration.

4

43 44 Chapter 04 Design and Fabrication

Formal Exploration_Biochar-Clay Units Unit Physical Building learning center Brick Tile Tile Formal Exploration through Material New Notions of Inhabiting Earth through Precedents, Formal Expression of Material, and Biochar Units Formal Exploration_Biochar-Clay Units Unit Physical Building Taichung Opera Theater Gallery of Louisiana State Museum Formal Exploration_Clay Modeling Figure 28|Formal Exploration through Material, New Notions of Inhabiting Earth through_Precedents, Formal Expression of Material, and Biochar Units Formal Exploration through Material New Notions of Inhabiting Earth through Precedents, Formal Expression of Material, and Biochar Units Precedents Formal Exploration_Biochar-Clay Units Unit Physical Building Taichung Opera Theater Gallery of Louisiana State Museum Formal Exploration_Clay Modeling learning center Brick Tile Prototype(?) Tile 45 46 Chapter 04 Design and Fabrication

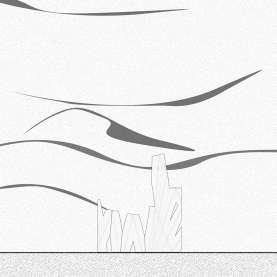

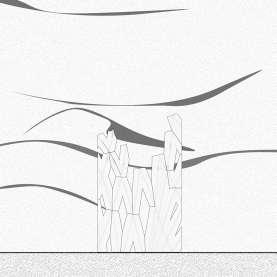

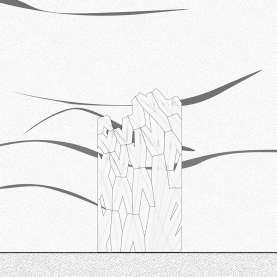

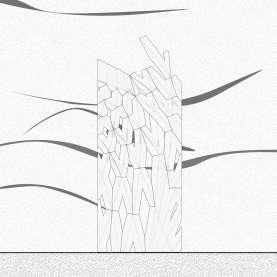

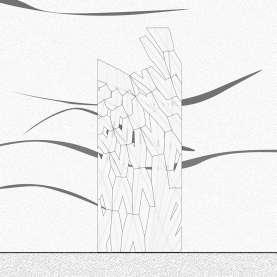

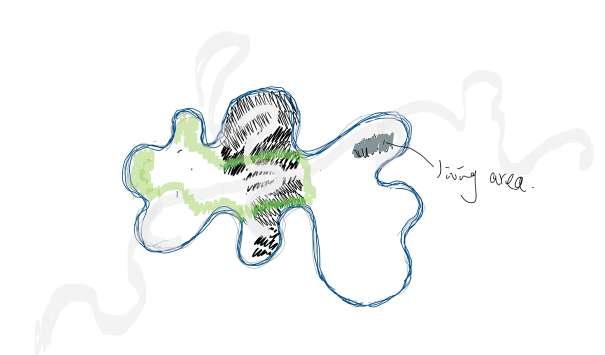

4-2_Site Testing_Red Water Pond Road 305_ NE Church Rock Rio Puerco Rive 303_NE_Church Rock No.1 Church Rock No.1_East Mill Site and Disposal Cells Uraniumout km0 20%5% 35% 40% 305_NE Church Rock Mine identify contamination contamination as raw material winddirection spray on land to improve the soil t exc tu re f or grazing me morial space mix with biocha r Figure 29|Red Water Pond Road Figure 30|site operation 47 48 Chapter 04 Design and Fabrication

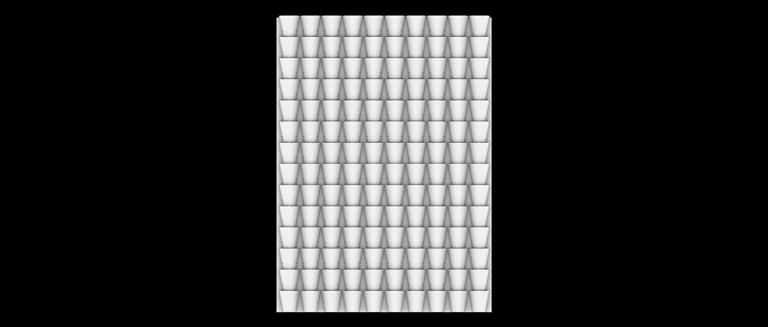

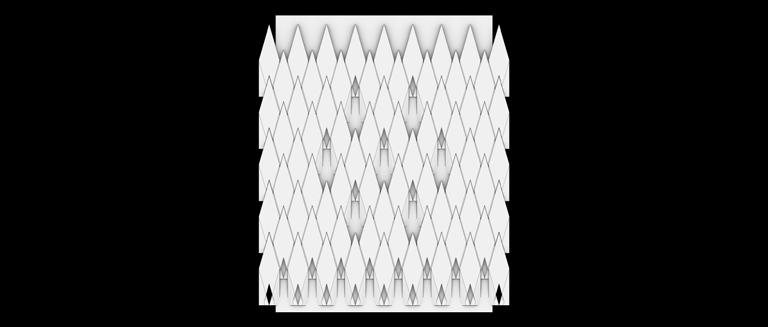

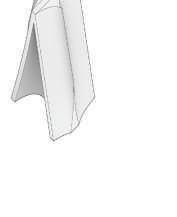

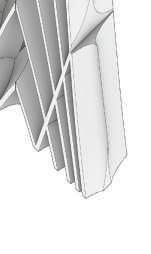

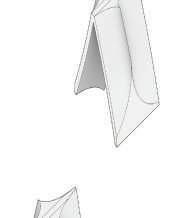

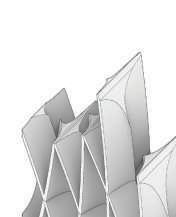

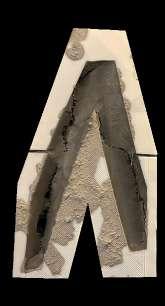

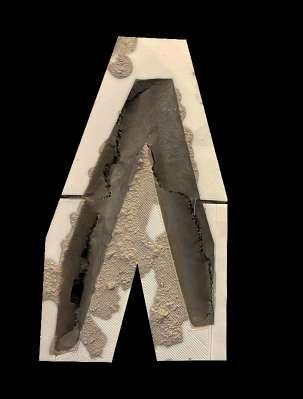

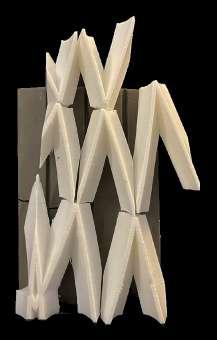

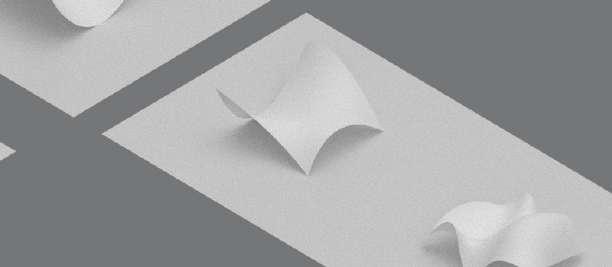

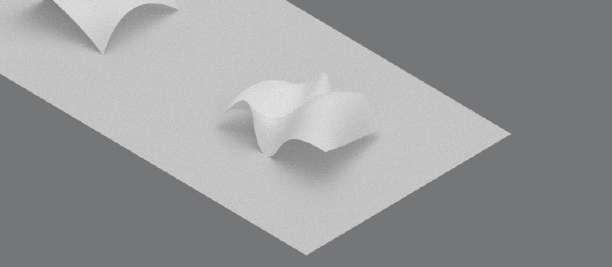

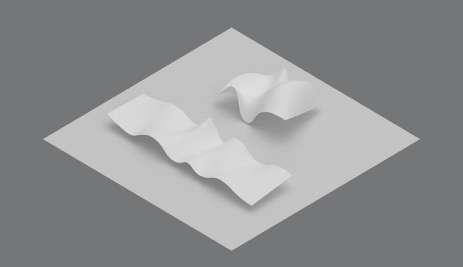

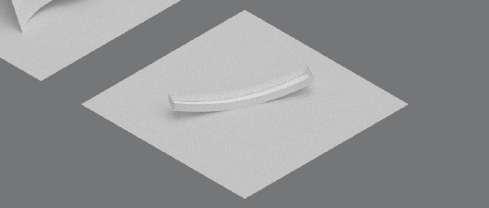

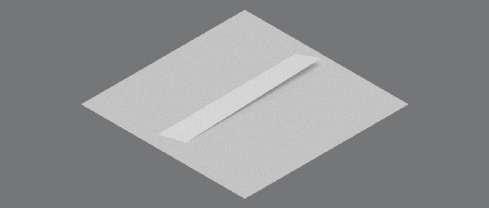

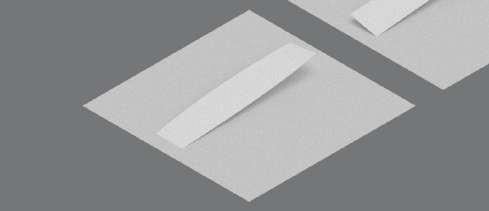

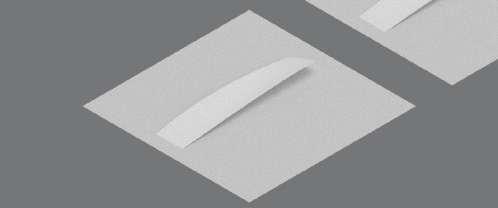

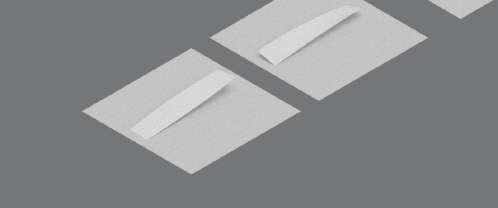

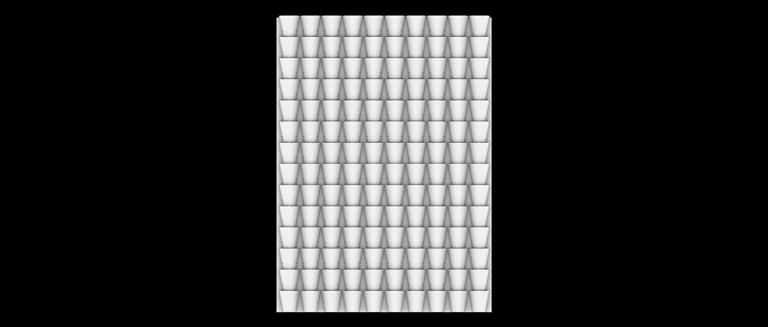

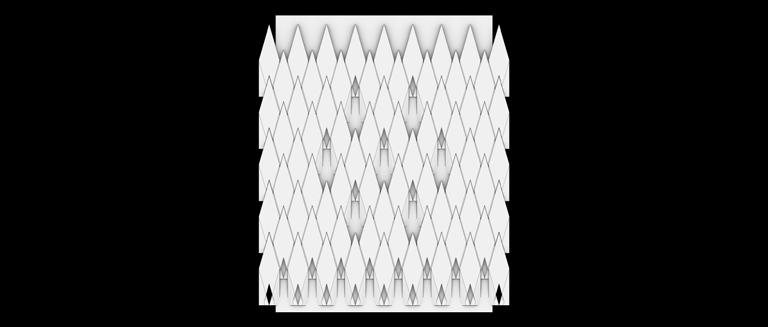

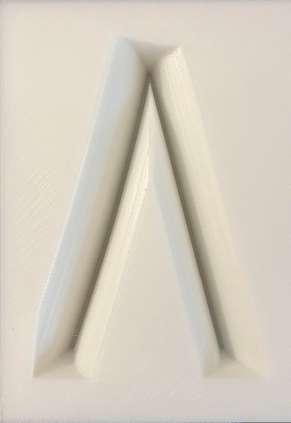

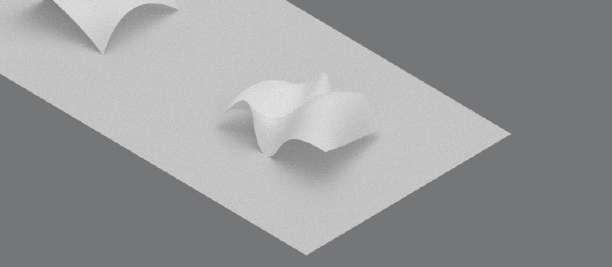

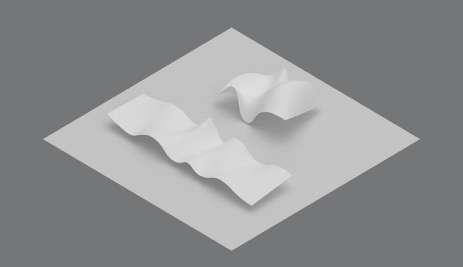

4-3_Moduling and mold

designed to be

in

much

Eventu

with earth as possible. It is not necessary to be self-standing since the earth is the major supprot for

choose the type four to do further

Geometry and pattern is

joined to soil

order to have

interface

it.

ally, I

developing. 1m excavatepress absorb 1m excavatepress 1m excavatepress absorb 1m excavatepress absorb replace and 1m excavatepress absorb replace and recycle excavate install absorab absorab absorab replace grind and recycle new units Figure 35|Lifecycle of the reinvented material Figure 31|Type 01 Figure 33|Type 03 Figure 32|Type 02 Figure 34|Type 04 49 50 Chapter 04 Design and Fabrication

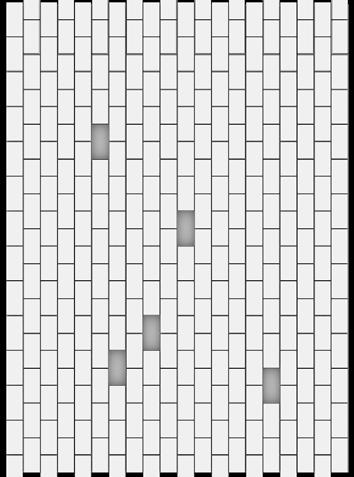

wall built by the reinvented mate rial is composed by several identical units. Each unit are placed with par ticular location which is decided by nearby units. On one side of each unit is pressed into earth, stuck with soil in oeder to absorb contamination. Each unit has particular mold units.

unit05 100cm/39in80cm/31in 60 cm/23 in unit05_mod_01 unit05_mod_02 Figure 36|Mold units unit01 unit02 unit05 + contamination biochar Figure 37|Mold units and building process A

51 52 Chapter 04 Design and Fabrication

Figure 39|mold unit 03_test 01Figure 38|mold unit 03_test 00 Figure 40|mold unit 05-01_test 00 Figure 41|mold unit 05-02_test 00 Figure 42|mold unit 05-02_test 01 Figure 44|mold unit 03_test 03 Figure 43|mold unit 05-02_test 02 Figure 45|3D printed units 53 54 Chapter 04 Design and Fabrication

Figure 46|Sequence of installation Figure 47|typical section of the wall 55 56 Chapter 04 Design and Fabrication

Figure 48|

re-excavated

mine Figure 49|re-excavated mine57 58 Chapter 04 Design and Fabrication

year 5 year 20 year Figure 50|reinvented biochar wall is reoccupied by the nature Figure 51|the regenarated wall reoccupied by the nature 59 60 Chapter 04 Design and Fabrication

Figure 52|rethinking the way of occupying 61 62 Chapter 04 Design and Fabrication

Heidegger, Martin, John Macquarrie, and Edward S. Robinson. Being and Time. Eastford, CT: Martino Fine Books, 2019.

McDonough, William, and Michael Braungart. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. Lon don: Vintage, 2009.

Latour, Bruno, and Catherine Porter. Politics of Nature: How to Bring the Sciences into Democracy. Cam bridge: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Yenice, Yagmur, and Daekwon Park. “Designing a Smart Geometric Configuration for Dry Masonry Wall.” Blucher Design Proceedings, 2019. https://doi.org/10.5151/proceedings-ecaadesigradi2019_508.

Mark Blitz, “Understanding Heidegger on Technology,” The New Atlantis, Number 41, Winter 2014. voxdotcom. (2020, October 12). How the US poisoned Navajo Nation. YouTube. Retrieved July 21, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ETPogv1zq08&t=563s&ab_channel=Vox

Yan Lin et al., “Environmental Risk Mapping of Potential Abandoned Uranium Mine Contamination on the Navajo Nation, USA, Using a GIS-Based Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Approach,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 27, no. 24 (2020): pp. 30542-30557, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-09257-3.

C. Arnold, “Once Upon a Mine: The Legacy of Uranium on the Navajo Nation,” Environ. Health Perspect. 122, A44 (2014).

Robinson, Paul; Hector, Alice; Luis, Judy; Benavides, David; Hancock, Don (1979), “Uranium Mining and Milling: A Primer” (PDF), The Workbook, Albuquerque, New Mexico: Southwest Research & Information Center, 4 (6–7), archived from the original (PDF) on July 8, 2010, retrieved December 9, 2012.

Grammer, Elisa J. (1981), “The Uranium Mill Tailings Radiation Control Act of 1978 and NRC’s Agreement State Program”, Natural Resources Lawyer, 13 (3): 469–522, JSTOR 40922651

B. Weil, “Uranium Mining and Extraction from Ore,” Physics 241, Stanford University, Winter 2012.

Bargar, J.R., Williams, K.H., Campbell, K.M., Long, P.E., Stubbs, J.E., Suvorova, E.I., Lezama-Pacheco, J.S., Alessi, D.S., Stylo, M., Webb, S.M., Davis, J.A., Giammar, D.E., Blue, L.Y., and Bernier-Latmani, R., 2013, Uranium redox transition pathways in acetate-amended sediments: Proceedings of the National Acade my of Sciences, v. 110, no. 12, p. 4506-4511, doi:10.1073/pnas.1219198110.

Rodriguez-Franco, C., Page-Dumroese, D.S. Woody biochar potential for abandoned mine land restoration in the U.S.: a review. Biochar 3, 7–22 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42773-020-00074-y.

Bibliography

63 64

EPA (Environmental Protection Agency), accessed July 31, 2022, https://www.epa.gov/remedytech/green-remediation-best-management-practices-min ing-sites.

W. I. Woods, Amazonian Dark Earths Wim Sombroek’s Vision, 2009

S. Gupta, H.W. Kua, H.J. Koh, Application of biochar from food and wood waste as green admixture for cement mortar, Sci. Total Environ., 2018

A. Mohammadi, A.L. Cowie, T.L. Anh Mai, M. Brandão, R. Anaya de la Rosa, P. Kristiansen, S. Joseph Cli mate-change and health effects of using rice husk for biochar-compost: comparing three pyrol ysis systems, J. Clean. Prod., 2017

S. Robb, P. Dargusch, A financial analysis and life-cycle carbon emissions assessment of oil palm waste biochar exports from Indonesia for use in Australian broad-acre agriculture, Carbon Manag., 2018

Close T. Mattila, J. Grönroos, J. Judl, M.R. Korhonen, Is biochar or straw-bale construction a better carbon storage from a life cycle perspective? Process Saf. Environ. Protect., 2012

Z. Liu, S. Singer, Y. Tong, L. Kimbell, E. Anderson, M. Hughes, D. Zitomer, P. McNamara, Characteristics and applications of biochars derived from wastewater solids, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., 2018

Y. Wang, R. Yin, R. Liu, Characterization of biochar from fast pyrolysis and its effect on chemical properties of the tea garden soil, J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol., 2014

Z. Zhang, Z. Zhu, B. Shen, L. Liu, Insights into biochar and hydrochar production and applications: a review, Energy, 2019

Q.V. Bach, W.H. Chen, Y.S. Chu, Ø. Skreiberg, Predictions of biochar yield and elemental composition during torrefaction of forest residues, Bioresour. Technol., 2016

Hans-Peter Schmidt, Ithaca Institute for carbon strategies, 2013

“Cast in Carbon,” IAAC Blog, Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia, 2016 https://www.iaacblog.com/programs/cast-in-carbon/.

65 66

Notes from Politics of Nature and Standing Reserve

Appendix

67 68

Notions of inhabitat through sections

69 70

71 72

73 74

75 76

Sinyu Lin Advisor: Nina Sharifi

Sinyu Lin Advisor: Nina Sharifi

Figure

Figure

Figure

Figure

mining wasteuranium

Figure

mining wasteuranium

Figure

Figure

Figure

Figure

Figure