ANNA ROGERS

georgia institute of technology

master of architecture

SYNTAXES OF PLEASURE

This is a proposal for a native horticultural farm complete with a native flower farm, native fruit tree farm, educational facility, restaurant, and lodging retreat.

At the beginning of the semester, we read Pliny’s Villas and were asked to identify key conditions and syntactic relationships that are important to the experience of inhabitation as described by Pliny and create collages depicting those relationships. The two primary themes that stood out to me were that of path and garden, as depicted in the collage on the top, and that of window and prospect, illustrated in the bottom collage. These two relationships became guiding principles in both my landscape and architectural design.

Apart from the native flower farm and fruit tree farm, the programmatic elements are distributed in alcoves along the tree line of the property and situated along their east-west axes to respond to both the climate and views of landscape. Vehicles travel along a relatively direct path through the farm to the lodging. The road traverses through the property instead of around the pond to maintain a sense of seclusion and serenity around the pond. Pedestrians enjoy a different progression through mature trees and the cultivated native farms. Extending from this main path are other pedestrian-only paths that lead to contemplative spaces within the landscape.

FALL 2022 | D+R STUDIO I | PROF. JOHN PEPONIS

FALL 2022 | D+R STUDIO I | PROF. JOHN PEPONIS

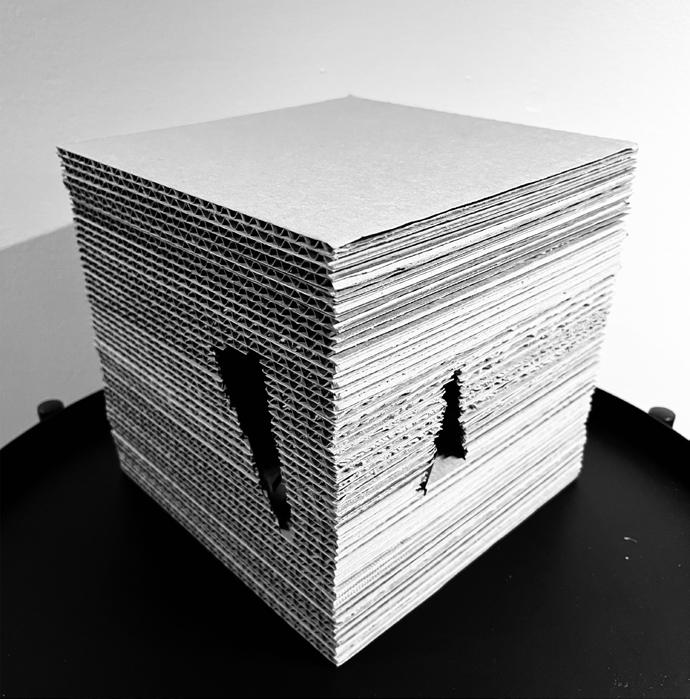

CENTER FOR HORTICULTURAL EDUCATION

The educational facility is located near the front of the property in order to reduce vehicular and pedestrian traffic in the core of the site and is intended for four simultaneous classes of 10-15 students each. My primary goal with this design was to create unique indoor-outdoor relationships and provide the opportunity for classrooms to extend into the landscape. The surrounding landscape consists of three distinct gardens (full sun, part sun, and shade) that are directly accessible from classrooms for courses to be directly related to the local environment, which also serves as a laboratory. Other indoor-outdoor relationships exist throughout the facility to accommodate informal discussions and visits. The lodging units are organized so that guests can enjoy expansive views of the flower farm, fruit tree farm, and pond.

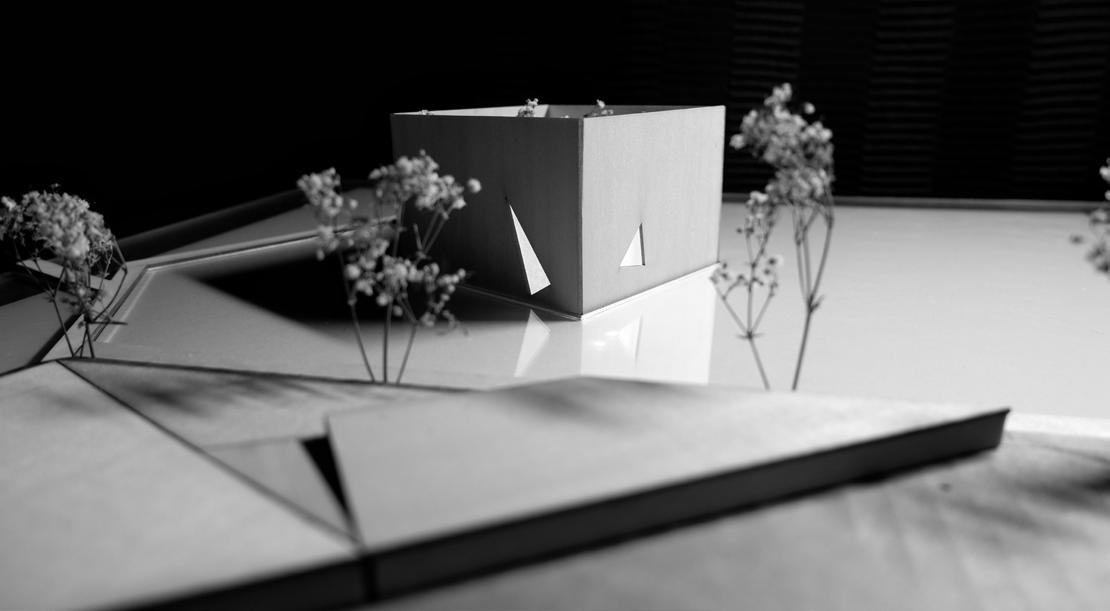

DWELLING PLACE

The lodging is located on the south-west side of the side to privilege expansive views of the farm. Each lodge was designed to have a unique view and access to semi-private garden patios. These lodges were designed to be spaces of contemplative refuge. Views of the farm are to the North, and a wall enveloped in flowering vines is to the South. From the bed and bath, visitors can gaze into the sky from a skylight.

ADAPTATION IN THE DELTA

This proposal consists of multiple typologies for a community in Mayersville, Mississippi. The structures and comprehensive community plan respond to environmental, social, and economic hardships facing the Delta region, an area challenged by rising sea levels and other climactic events.

The structures are designed to respond to conditions of periodic flooding and irregular weather events. Mass timber and/or additive manufactured concrete were required as building technologies. The buildings support regular transportation and mobility, integrate with economic activity of the area, and are designed to provide resilient, supportive, and community cohesion.

SPRING 2022 | ADV STUDIO I | PROF. DANIEL BAERLECKEN

REGIONAL COMMUNITY PLAN

Mayersville, MS is located in an area with reduced flood risk due to the levee. According to FEMA’s national flood database, it has a 0.2% annual change of flood hazard. Surrounding farmland, however, is subject to a 1% annual chance from backwater overflow.

An often unknown quality of the Mississippi Delta region is that is the Lower Mississippi Alluvial Valley Forest was once the second largest forest in the world—just behind the Amazon rainforest—prior to massive deforestation efforts that began in the early 1900s for agricultural production. These efforts led to an approximately 75% reduction of forested land, from 25 million to 5.5 million acres, with more than half of the deforestation occurring between 1930 and 1980. Even before the colonization of Mississippi and Louisiana, indigenous people in the region had utilized the nutrient-rich delta soil for agricultural purposes, signalling a further human-initiated deforestation of the valley that has gone on for potentially thousands of years.

Today, images of the delta have almost no resemblance to a forest. Tree canopies help mitigate flooding by intercepting rain from reaching the ground, while root systems help to absorb excess water, stabilize soil to prevent erosion, and create channels within soil for increased permeability. With the long-term removal of trees and their replacement with looselypacked, frequently-tilled soil, these natural flood mitigation strategies are also removed, creating conditions that are ripe for inundation.

At a regional level, this proposal restores commercial farmland to wetland forests to combat the destruction of the regions natural habitat. By removing commercial farmland, the land would be given back to the community and offer an economic opportunity for residents to obtain jobs as park rangers and forest maintenance workers. Reforestation also allows wetland regions (dotted hatch) to be reconnected, which would direct water movement away from Mayserville.

This proposal also includes relocation of the courthouse from the center of the community to be adjacent to the jail. This allows a central plot of government land to be re-purposed into a community zone for the residents of Mayersville. Finally, this proposal incorporates the construction of a boardwalk through the forested edge of the Mississippi River to afford community access from the river.

LOCAL COMMUNITY PLAN

The town of Mayersville suffers from a poor economy and lack of strong community engagement. At a local scale, this proposal incorporates changes to improve economic stability and increase community engagement. To encourage community growth through densification, plots of land can be divided and sold or leased for the construction of the two new proposed houses. Other plots of land can be re-purposed into community gardens to generate produce for the local grocery in the proposed community center. For community resilience from seasonally high groundwater tables, existing swales are bio-diversified and extended as an interconnected network of swales throughout the community (blue lines). These swales are designed to divert water away from the community to the reforested wetland. Elevated boardwalks are constructed above these swales and provide a means of navigating during wet seasons when the ground becomes over saturated with water (dashed lines). The boardwalks connect to new and existing house in addition to the community center so that, during extreme weather events, the community can remain connected and accessible.

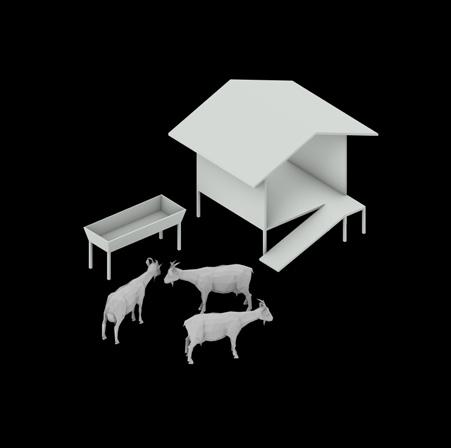

HOUSING PROTOTYPES

The Single Family House is a 3BD, 2BA, 1500SF house designed for a family of 4. The Flex House is a 2BD, 2BA, 990SF house designed for a single person or couple looking to generate income by renting a bedroom to tourists.

Both houses are composed of cross-laminated timber and 3D printed concrete, and are clad in shou sugi ban wood to combat high humidity levels. Front porches a hallmark of houses in the south— were a driving design factor to enhance community connection and encourage connection to the outdoors.

To combat flooding, both houses are elevated 4 feet above grade on stilts and connected to an elevated boardwalk.

SECTION H1

COMMUNITY CENTER PROTOTYPE

The Community Center is centrally located within Mayersville and consists of a large event space, public library, produce market and cafe, and a nature preserve center.

By elevating the center 20 feet off the ground, shaded space beneath the platform becomes available as an area for tennis and basketball courts. With the hot and humid climate in Mayersville, this provides a comfortable space for the community to gather and play sports in the warmer months.

This design was also driven by the front-porch typology to enhance community connection and encourage the use of outdoor spaces. Circular punctures in the platform allow trees to grow through and provide non-architectural shading for certain areas of the open deck. An emphasis on reconnecting inhabitants with the restored natural habitat was important to encourage a new relationship with the environment.

RECONSTRUCTION

SPRING

LENA KLEIN

Analysis of the RGA Headquarters building by Gensler. 3D digital reconstruction of the southeast corner by thorough investigation of 2D construction documents.

PARAPETT/STEEL73’-11.5”

LEVEL05T/STEEL56’8.5”

2 SE.400

IBS 2, PHASES 3 + 4

DRAWINGS BY: ANNA ROGERS KEY PLAN

LEVEL04T/STEEL42’-8.5”

1 SE.300

LEVEL03T/STEEL28’-8.5”

2 SE.300

PARAPET 74’-6” LEVEL05 57’3” LEVEL04 43’-3” LEVEL03 29’-3” LEVEL02 15’-3”

1 SE.400 2 SE.200

LEGEND STEEL FRAME CONSTRUCTION WITH STRUCTURAL SILICONE GLAZED ALUMINUM UNITIZED CURTAIN WALL SYSTEM ATOP CONCRETE FOUNDATION

LEVEL02T/STEEL14’-8.5”

SE CORNER 1 SE.200

LEVEL01T/STEEL-0’-6.5”

A SE.100 1 SE.101

OVERALL VIEW SOUTHEAST CORNER

35

IBS 2, PHASES 3 + 4

DRAWINGS BY: ANNA ROGERS

RGA HEADQUARTERS GENSLER, PROJECT ARCHITECT

KEY PLAN

LEGEND

1. CONCRETE WALL

2. PLANTINGS, AGGREGATE

3. EARTH/GROUND

4. CONCRETE SLAB

5. STONE (3” LIMESTONE PANELS)

6. MORTAR

7. WEATHER BARRIER

SE.101

1 SE.101

2 SE.101 1/2” = 1’

LANDSCAPE WALL, ENCLOSURE 1/2” = 1’

LANDSCAPE WALL, SUBSTRUCTURE

TALL LANDSCAPE WALL REF 2/A6.403

1 SE.101

2 SE.101 1/2” = 1’

LANDSCAPE WALL, ENCLOSURE 1/2” = 1’

LANDSCAPE WALL, SUBSTRUCTURE

TALL LANDSCAPE WALL REF 2/A6.403

IBS 2, PHASES 3 + 4

DRAWINGS BY: ANNA ROGERS

RGA HEADQUARTERS GENSLER, PROJECT ARCHITECT

KEY PLAN

LEGEND LEVEL 01 ALUMINUM WINDOW WALL FRAMING TO LEVEL 02 UNITIZED CURTAIN WALL FRAMING, SHOWING SOFFIT CONDITION WITH COLD FORMED FRAMING SUBSTRUCTURE AND ALUMINUM TRIM

LEVEL 01 - LEVEL 02

GLAZING

GLAZING

IBS 2, PHASES 3 + 4

DRAWINGS BY: ANNA ROGERS

KEY PLAN

LEGEND

LEVEL 01 ALUMINUM WINDOW WALL SYSTEM TO LEVEL 02 CURTAIN WALL SYSTEM SHOWING SOFFIT CONDITION

WINDOW WALL AT LANDSCAPE AND SOFFIT/ CURTAIN WALL AT SOFFIT REF 11/A4.007

RGA HEADQUARTERS GENSLER, PROJECT ARCHITECT SE.201

IBS 2, PHASES 3 + 4

DRAWINGS BY: ANNA ROGERS

RGA HEADQUARTERS GENSLER, PROJECT ARCHITECT

KEY PLAN

LEGEND

1. ALUM. MULLION

2. ALUM. SILL

3. CONCRETE SLAB

4. STRUCTURAL SILICONE

5. IGU WITH LAMINATED INBOARD LITE

6. SEALANT

7. BACKER ROD

8. PRESSURE PLATE

9. TRIM COVER

10. WEATHER BARRIER

11. FILTER FABRIC

12. PROTECTION BOARD

13. RIGID INSULATION

14. ALUM. TRIM

WINDOW WALL SILL REF 1/A6.403

IBS 2, PHASES 3 + 4

DRAWINGS BY: ANNA ROGERS

RGA HEADQUARTERS GENSLER, PROJECT ARCHITECT

KEY PLAN

LEGEND

1. COLD-FORMED C-SECTION

2. WINDOW WALL HEAD

3. GROUT

4. SHEATHING

5. SEALANT

6. WEATHER BARRIER

7. BLOCKING

8. BACKER ROD

9. 1/8” ALUM. ANGLE

10. RIGID INSULATION

11. ALUM. CLADDING WITH ATTACHMENT PIECES

12. STRUCTURAL SILICONE

13. PRESSURE PLATE

14. IGU WITH LAMINATED INBOARD LITE

WINDOW WALL HEAD AT SOFFIT REF 19/A6.200

IBS 2, PHASES 3 + 4

DRAWINGS BY: ANNA ROGERS

RGA HEADQUARTERS GENSLER, PROJECT ARCHITECT

KEY PLAN

LEGEND

1. CURTAIN WALL ALUM. SILL

2. SHEATHING

3. RIGID INSULATION

4. ALUM. SHADOWBOX

5. GROUT

6. WEATHER BARRIER

7. IGU WITH LAMINATED INBOARD LITE

8. ALUM. CLADDING

9. STRUCTURAL SILICONE

10. SEALANT

CURTAIN WALL SILL AT SOFFIT REF 1/A6.100

IBS 2, PHASES 3 + 4

DRAWINGS BY: ANNA ROGERS

RGA HEADQUARTERS GENSLER, PROJECT ARCHITECT

KEY PLAN

LEGEND TYPICAL LEVEL SHOWING ALUMINUM UNITIZED CURTAIN WALL SYSTEM WITH INSULATED SHADOWBOX

TYPICAL LEVEL 02-05 AT SHADOWBOX

KEY PLAN

LEGEND

1. ALUM. CURTAIN WALL STACK JOINT

2. CURTAIN WALL ANCHOR

3. ALUM. TRANSOM

4. ALUM. TRIM

5. GROUT

6. SEALANT

7. FIRE STOP

8. POUR STOP

9. ALUM. SHADOWBOX

10. RIGID INSULATION

11. IGU WITH LAMINATED INBOARD LITE TYPICAL SHADOWBOX

RGA HEADQUARTERS GENSLER, PROJECT ARCHITECT SE.301

CORNER MULLION, SUBSTRUCTURE

CORNER

IBS 2, PHASES 3 + 4

DRAWINGS BY: ANNA ROGERS

RGA HEADQUARTERS GENSLER, PROJECT ARCHITECT

KEY PLAN

LEGEND

1. ALUM. CORNER MULLION

2. RIGID INSULATION

3. SHADOWBOX

4. IGU WITH LAMINATED INBOARD LITE

5. SEALANT

CORNER MULLION AT SHADOWBOX REF 2/A6.102

SE.302

MULLION + ANCHOR, SUBSTRUCTURE

IBS 2, PHASES 3 + 4

DRAWINGS BY: ANNA ROGERS

RGA HEADQUARTERS

GENSLER, PROJECT ARCHITECT

KEY PLAN

MULLION + ANCHOR, ENCLOSURE

LEGEND

1. ALUM. SPLIT MULLION

2. ATTACHMENT BOLT

3. METAL ANGLE

4. STEEL CHANNEL

5. STEEL POST

6. POSTS EMBEDDED IN GROUT (GHOSTED)

7. IGU WITH LAMINATED INBOARD LITE

8. SEALANT

9. RIGID INSULATION

10. ALUM. SHADOWBOX

11. ALUM. TRIM

TYPICAL LEVEL TOP OF SLAB ANCHOR AT SPLIT

MULLION

REF. 12/A6.102 + HALFEN HCW

SE.303

IBS 2, PHASES 3 + 4

DRAWINGS BY: ANNA ROGERS

RGA HEADQUARTERS

GENSLER, PROJECT ARCHITECT

KEY PLAN

LEGEND

ALUMINUM UNITIZED CURTAIN WALL SYSTEM AT PARAPET LEVEL

1. COLD-FORMED FRAMING

2. HEAD

3. CONCRETE SLAB ON TOP OF METAL DECKING

4. MULLION

5. SPLIT MULLION

6. TRANSOM

7. CORNER MULLION

PARAPET LEVEL

SE.400

WAIT AND WONDER

This project is a proposal for a new ferry terminal in the city of Miyajimaguchi, Japan. The proposal incorporates an important urban outdoor public space that has a significant relationship to the station and its auxiliary structures. The ferry terminal is a significant threshold between Japan’s mainland and the island god, Miyajima, home to the Itsukushima Shrine. Approximately 26,000 people pass through the terminal every day.

This building is unlike any building ever before experienced. It has a strong presence when seen from the outside, and contrasts greatly with its surrounding context. It plays a role of “forgetting” in forming a new experience by capturing attention and compelling the occupant to be fully present in the space and thus “forgetting” their immediate past.

This project was conceived by exploring various architectonic phrases and ordering systems. As described by Valerio Olgiati, the architectonic idea is not a description of a building – it contains many possible buildings. Furthermore, an architectonic idea must be “form generative” and “sense making.” The following architectonic phrase was used as a guide for the design of this project: an underground tunnel that leads to voids within a solid.

Pedestrian Paths

Train Station

Ticketing

Pedestrian Promenade

Underwater

Pedestrian Path

Waiting Room & Restaurant

Docking Hub

Vehicular Path

Ferry Dock

SPATIAL MECHANISMS

Derived from a single point, this parametric spatial mechanism utilizes a cube and three spheres to create a variety of geometric constructs. The Grasshopper definition incorporates numerous modes of input, various relational hierarchies, and data flow logics- such as if-then conditions- to produce unique spatial domains. The cube acts as a boundary condition and the intersection of a sphere with any face of the cube triggers a unique output on the face of the cube. When the spheres do not intersect with the cube, points along the surface of each sphere create a network of nodes from which lines originate to create volumetric cells between the spheres and the cube. When the spheres intersect with cube, these cells disappear and a network of lines is constructed from the same surface points using a Delaunay triangulation computation. As the spheres move in space, the distance between these points change and, thus, change the network of lines.

line length < 7.5 cm

line length < 7.5 cm

A

volumetric voronoi diagram changes with relationship to sphere size and location

intersection with west and/or south borders triggers planar voronoi diagram scaled in relationship to distance from center point of sphere_03

C

A NEW PRECEDENT

In this course, every student was assigned a building to analyze in section and plan. Each building was a precedent for the following design modes: folding, stacking, suspending, aggregating, eroding, layering, wrinkling, packing, and aggregating. Villa VPRO by MVRDV (top right) was assigned as my precedent, and folding is its primary design mode. All students shared their plan and section drawings in order for each student to create a composite drawing that repeated elements from other precedents but maintained the primary design mode from our original precedent. The patterns I chose to repeat were extracted from three precedents in section, including Villa VPRO, Phillips Exeter Library, and Karlowicz Philharmonic. These elements, highlighted in yellow below, were scaled, rotated, mirrored, and repeated to create a new “folding” precedent in section, which is illustrated on the following page.

SUMMER 2021 | CORE STUDIO III | PROF. DANIEL BAERLECKEN Karłowicz Philharmonic Barozzi Veiga (drawing by Ian Matthew Morey) Phillips Exeter Library Louis Khan (drawing by Suzanne Shorrosh)FOLDING ON THE BELTLINE

Elements from the aforementioned composite drawing were extracted, reconfigured, and extruded to create a building to support several disparate programs, all of which have different spatial requirements for functioning. Situated on the Beltline in Atlanta, GA, this building invites people to explore the various programs on foot or wheels by way of various public terraces and bike ramps.

cheese production

goat farm

climbing

flexible event space

3D ceramic fabrication

archery

bar

3D bicycle fabrication

bicycle track

cheese production

goat farm

climbing

flexible event space

3D ceramic fabrication

archery

bar

3D bicycle fabrication

bicycle track

3D bicycle fabrication

3D ceramic fabrication

flexible event space

goat farm

archery

goat cheese production

bar

public terraces

climbing

3D bicycle fabrication

3D ceramic fabrication

flexible event space

goat farm

archery

goat cheese production

bar

public terraces

climbing

CONVERSATION

A conversation about evidence-based design with Camilla Moretti, Principal Architect at HKS, and Michael Gamble, Director of the Master of Architecture Program at Georgia Institute of Technology.

Thank you so much for taking time out of your Friday afternoon to talk to us! I’d like to kick it off by allowing you to introduce yourself and then we’ll jump into the questions.

Camilla MorettiThank you for having me! My name is Camilla Moretti. I am an architect and healthcare planner for HKS. I am the health studio leader for the Detroit office and work with a lot of different offices nationally within our HKS world. I’ve been with HKS for 14 years now. I joined right after grad school and have been lucky enough to work with the best in the market. Our Detroit office is one of the research hubs for HKS and I am privileged to work with Dr. Upali Nanda, who you probably know from the health-design world. She’s fantastic and I’ve had many, many opportunities to work with her on applied research projects. So, looking at some of your questions, I’m like– this is fantastic. I’m very interested in combining operations and lean thinking into design and applying research– either evidence that exists or, when it doesn’t exist, trying to find what we know and do the applied research as part of our project. So, within our design continuum, we talk a lot about trying to insert and integrate research at every step of the way.

A.R. Wonderful, thank you. Can you tell us a little bit about what evidence-based design means to you?

C.M. To me, the thing that we look at is all of the data that’s out there. You can’t do all the research yourself, so we like to leverage the types of research and information that peers are doing and things that are available in peer reviewed journals. It’s really looking at what is hearsay, what is anecdotal information, and what really has data to support it. A lot of times it’s not just evidence-based design, it’s evidence-influenced design. There are certain things that are solutions to each problem that our clients might have that are not exactly prescribed by the evidence, but you can connect back to evidence. Does that answer your question?

A.R. Absolutely, yes, and it leads me into the next one about working with clients. I was wondering if there is any resistance from clients to engage in applying the evidence?

C.M. Well, when you work with health systems, they are very empirical in their own way of working. A lot of times when we talk about different aesthetics and things that are a little more subjective – that is harder for them to grasp. Data is the language they speak. I found that using data to help support a design is a lot more successful than anything. And they appreciate knowing that there are things that are supportive of a design strategy and things that are not supportive of the design strategy. You know, what are certain things that are proven by data and some of the things that are good anecdotal data, but not quite yet a study that they might be up for participating in as part of a deeper dive study. We actually had that with ProMedica, the system up here in Ohio, and they were on board with doing an applied research project for pre-design to help guide the design of their new in-patient tower. And through that we were able to gather a lot of really good data, and use that data to help define the design of the new units. And we were able to test some parametric tools in real time that HKS had developed. We’re finally going back on site to do our functional performance evaluation, our POE. So, we are now closing the loop – the informational loop – on that project. And they were just such fantastic partners. Very interested in the evidence and, where there wasn’t evidence, how can we get that information based on a deep dive study.

Michael GambleI had one follow up question- well, it was really more of an observation. Architects, I think, were complicit in magical thinking about evidence related to energy consumption. Architects, for the longest time, drew these magic arrows that suggested air flow that never really went anywhere. But now, if anything, it’s given architects more purpose to say that applied research and evidence actually matters. And that we can learn through post occupancy evaluation and evidence-based research. So, my question would be related to those, what’s next in the area of evidence-based design? I know Anna may have that question, but I couldn’t help following up anecdotally related to magical thinking.

C.M. One thing that always comes back – and I think it’s kind of the missing loop – is: how can we attach any of the evidence to a bottom line? For example, we know that there’s a lot of evidence and different strategies that supports point-of-care supplies, but to make the case to a client that they need to do this because it’s going to save X amount of money or X amount of hours…that’s kind of the missing piece. It’s showing the ROI [return of investment], and I feel like that’s where we could really connect the whole spectrum of evidence and design and the operations. Putting that all together and understanding, what is the return on investment making this decision? We talk about, well, there’s more nurse time at bedside. Well, how much more? What does that mean? How does that translate? Does that truly translate in higher HCAB [healthcare access barriers] scores? For example, do I have a lower incidence of falls because nurses are closer to patients? Those are some of the things that go from the overall database and having some of that more applied to projects where we can get actual percentages; that hard data to share with our clients would be very important.

A.R. Great, that’s wonderful. My next question is related to billing. Do evidence-based design services cost more? How does your firm bill for research versus design services?

C.M. Well, I think that good design is evidence-based design. Good design is based on best practices and what we know of. That is baseline services, so that doesn’t cost anymore. Something that would be an additional service or a service that we provide to our clients is that additional deep dive research that’s applied to that project. So, if there is a question or something that would require X amount of hours from our team to do a deep dive shadowing or observation or survey– those kinds of things that are more on the applied research side– that would be considered an additional service or a service that we can provide our clients. But just to be able to apply evidence-based design strategies to a project– that should be every project. Every project should start with that baseline.

A.R. I’m really happy to hear that.

MG: Me too, I mean, we’re coming to you from Georgia Tech – you know we like evidence.

C.M. I mean the whole point is, there is data out there. If you’re not keeping up with it and understanding different systems… you can’t work with everyone right? So, if there are lessons learned or good things to learn from other systems, other researchers, other studies… that would just not be smart not do it, you know? So, why make the mistake? If we know something doesn’t work, why would we want to do that to our project?

...good design is evidence-based design. ”

A.R. So how do you keep up? Are literature reviews or journal clubs part of normal practice at your firm or do you keep up with it on your own?

C.M. All of the above. A lot of times when we start a project, we do have lit review. What do we know? What’s out there? And then we do have a lot of internal knowledge sharing opportunities. I personally run a monthly session of planning– early on pre-design and planning information– that’s a national call. Every month presents something different and we have a library of everything that you could think of. So, it goes from full on formatted to a little more prescriptive presentations to just conversations on, ‘what did you learn this week?’ Or, you know anything that the teams want to share– the good, bad and the ugly. The internal knowledge sharing that we have is pretty robust and our research team internal to HKS is really good at sharing, even if it’s small little bites of different articles, different things. They actually are very good at synthesizing a paper into– you know, for those of us that are not researchers–[something we] understand and kind of just get to the point. Like, the executive summary of that enormous paper, this is what we need to focus on. They’re really good at doing that so we can keep up with that information that’s available.

A.R. Excellent. That’s really encouraging to hear. So, changing gears a little bit, I want to talk about postoccupancy analyses. I’m curious- what percentage of projects does your firm perform a post-occupancy evaluation on?

C.M. Sometimes, as part of the project on the get go we’ll do a functional performance evaluation and at the end a year, usually a year after. I personally have done four or five big projects that we had identified early on. There were things that we had applied during design that we, as a firm, wanted to verify how it worked, what worked, what didn’t. It’s always a great way to close that information loop.

A.R. And what do the post-occupancy evaluations usually look like?

C.M. We do a survey, we do interviews with key stakeholders, and we go and shadow. So there’s observational data as well as different key performance indicators that we identify early in the design and want to measure after the fact. So we take those key data points and document those as well. It’s a multi-faceted approach. We want to make sure that we are walking the walk, that we are there with them and doing the shadowing. One thing that we learned earlier on is that, if you’re just doing interviews, the human brain has a way of smoothing through hiccups. We had this very interesting process where we were doing current state mapping with nurses. They were describing their process and it was so very linear and beautiful. At the same time along side of [the interviews] we were doing the observations and we were like, “Well we noticed that you had to go to the nourishment room four times for that one medication event, they’re like, oh, I never thought of that.” So it’s really going and seeing– the lean terminology, going to Gemba– where the work is being done and learning from that is key. I gotta tell you, clinicians are fantastic at making things work. You know we joke around– it’s the good, the bad, and the work around because they’re going to provide care, the architecture supporting it or not, so they will make it work, and they’re fantastic at it. So, our job as architects is to really look at their process and see how we can make that better, make it easier for them. And, ultimately, it improves patient experience.

A.R. What types of buildings or settings present the biggest challenges in applying evidence to?

C.M. I think every project has its own set of challenges. I mean you have those very complex renovations that a lot of times is having to deal with existing structure, existing MEP, things that you just can’t go around. But there’s nothing that prevents you from applying the concept of evidence-based design. It’s all about framing and getting that rapport with the client that you know they understand. It’s always an education process, right? They don’t do [design] every day. They live in it; they live the space. They’re the experts on how that space functions. But we design spaces every day. So, we work together with our clients to establish what’s relevant of the evidence that we have available. How can we apply it to improve the processes that happen within the space? And how is that going to improve their operations? How is that going to make their lives easier? Really, that’s the whole point. Why would somebody spend millions of dollars to do a renovation or an addition or a brand-new greenfield hospital if we’re not trying to make their

lives and their patients’ lives and their staffs lives easier and make them more efficient? So, I think every project has its challenges is just identifying [the problems]. I think that’s really the beauty of our job – is understanding the challenge and rising to that challenge; to deliver a beautiful project that works really well.

M.G. Have you participated in interviews with patients who believe that their experience in one of your newer evidence-based hospitals or healthcare environments contributed to faster healing, better state of mind, etc?

C.M. So, the interesting thing with a lot of the research that we do is that anytime that you are dealing with clients, you have the IRB (institutional review board). So, a lot of times what we do is focus on the PI, the performance improvement area. We get the relationship of where the HCAB scores were before and where the HCAB scores were after. When we do have access to patient-family information, absolutely, that is such a wonderful connection to have. We don’t get that in every project, unfortunately.

M.G. You know, I’m the kid who didn’t like blood growing up. I just wasn’t interested in medicine. We have a number of doctors in the family and they’re big believers in [biophilia]. They’re also, increasingly, bigger believers in homoeopathic treatment and just exercise, you know, just common-sense stuff that people feel like they need a prescription, or they need to see a doctor for, and it really just has to do with the simple things. And I can imagine the same applying to hospitals. You go through all of the filters of reason, as healthcare was emerging as a major discipline in the industrial period, but then common sense falls out of the equation. And then it finds its way back in. Part of my feeling about evidence-based design– or evidence-influenced design, which I really like, very clever– I like the fact that common sense finds its way back into the room.

C.M. You know, and it’s so funny because, to me, the best designs are simple. There’s something just so beautiful that you can walk into a space and intuitively know where you’re going. That’s one of the biggest issues with healthcare. It’s usually a very large building and you’re catching people at their worst. Can we make it so that it’s simple? That common sense, as you’re saying, can be the guide? Providing our patients and our staff

...just to be able to apply evidence based design strategies to a project –that should be every project. ”

what they need when they need it. It’s just so simple, right? Providing them with what they need, when they need it. It’s a simple concept, but something that is so very important, and I think that is one of the big things when I look at a plan and I’m working with the with the team. The thing I want is for them to think is, “Wow this is very simple.” Because simple is hard to do. That the point is trying to bring in simplicity and something that’s intuitive, too. Provide that connection back to the outside so they can reorient themselves. We have museum syndrome in a lot of our hospitals where you don’t know what’s North, South, East, West, anymore because you don’t see a window and you can’t tell.

A.R. This has been great and was incredibly informative. We are about at time, so I don’t want to hold you up any longer. Thank you so much for taking time out of your day to chat with us.

C.M. My pleasure.

A.R. I hope you have a wonderful rest of your Friday afternoon and a great weekend.

C.M. Thanks, you too. See you guys!