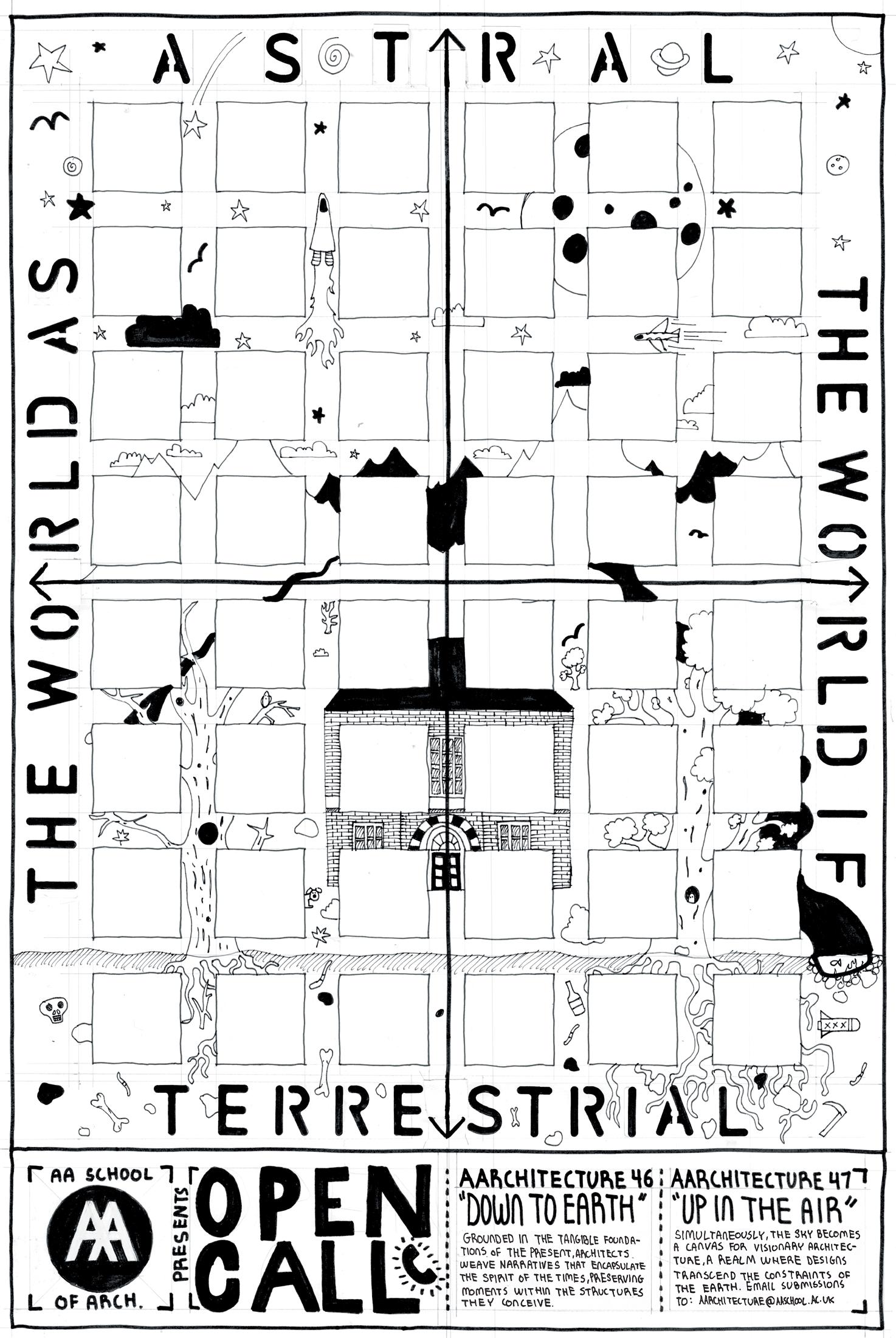

AARCHITECTURE 46

The AA smells different this year. It’s fresher, sweeter even. Is it Pascal’s cooking? That has certainly improved, but no, that’s not it. It’s hard to pin down exactly what has changed. There’s a faint air of sawdust, graphite and … petrichor? Is it coming from the workshop? No, it must be the clay drying in Diploma 21. Maybe a long breeze carried it all the way from Hooke? We’re not sure. What we do know is the school is changing. Slowly. Thoughtfully.

A stranger might wander into 36 and note the strange absence of drafting tables. ‘I thought this was an architecture school?’ they might exclaim. What they don’t know is the school disposed of them years ago. Wander through the corridors and you might say this was premature. More and more of us are ditching the computer and picking up the pen. Perhaps this is pushback against exploitative firms treating us like CAD monkeys. Maybe we’re facing obsolescence head-on, arming ourselves with physical skills for when AI replaces us. Maybe we’re realising that fast-paced, overambitious development is leading to massive resource extraction while fuelling the climate crisis, displacing the poor and concentrating wealth and power in the hands of fewer and fewer people. Or maybe we’re revelling in the pleasure of simplicity: the satisfaction of a salvaged bit of timber sanded with 400 grit and smothered in linseed oil.

With issue 46, ‘Down to Earth’, we wanted to take the temperature of the room. We know it’s getting hotter, and we know that a lot of us are

feeling the effects. For some, this has made the role of good design ever more pressing. For others, this has led to existential dread and a sense that design and newness are unnecessary luxuries created by financial markets to sell excess. Both are totally reasonable responses. This issue spans the thermometer, from Jan’s icy conjuring of Arctic outposts to the heat of the AA’s carbon emissions recorded by a group of Environmental and Technical Studies (ETS) tutors. From deep within the soil, brought to life in Reshma’s microscope, to the valuable peat layer described by Clara, to the grounded assemblages constructing Julia’s shrines, ‘Down to Earth’ is firmly rooted in the current life of the AA.

Maybe this new smell is the scent of hope. It’s the smell of defiance. It’s a collective breath, quietly saying: ‘I can no longer sit by the status quo. I will no longer enable the system that will deprive my future’. We think many of us are waking to this reality. What is this all for anyway? What is the end goal of capitalism? What is architecture for if we’re all living in bunkers, hiding from the summer highs?

To us, picking up the pen is the architectural equivalent of touching grass. If you spy one of us walking around the gardens at Bedford Square, chances are you’ll find us barefoot.

Sincerely,

Jay, Tatiana, Leela AArchitecture editors.

Inhale.

Soil. Exhale. Oxygen. Inhale. Rot. Exhale. Carbon.

My breath caresses its roots.

My tongue tastes his dirt.

My eyes see her green.

My ears crackle with their unseen crawling.

My skin is wet.

My skin is dry.

My self deflates and expands.

Plant.

Soil Worm. Rope. Me.

HHHHHaaaaaahhhhhhh

Bliss.

I never want to feel the cold hatred of stone and concrete. I want to be enveloped, take care of, and be cared for.

Skittering legs run between my feet and the moss.

Endless amounts of strokes, jabs and kisses. A continuous flow of nourishment.

Only the forest can heal; safeguard me. I can stand tall as a tree here, as one of them.

They are my family, they understand me. I am bound and unwoven.

Muzzle: Breathe the soil.

Sandals: Touch some grass.

Shoulder Harness: The forest has got your back.

THOMAS

These models were inspired by BDSM visuals and ecosexuality, binding the human and the plant into one body. Through these models, bodily sensations are taken over by the forest, and the body becomes the vessel from which the forest gives birth.

Clara Olóriz Sanjuán, Elena Luciano Suastegui and José Alfredo Ramírez Galindo

Sequestered in the earth, released into the air: the carbon cycle continues. Carbon is captured by microorganisms through soil matter decomposition and is emitted in countless excavations, by tillage, burning, eruptions, extractions and even respiration. Violently disturbed ever since the start of the imperial project, carbon shakes our conceptions of time. Our present living conditions are ‘never made in the present’. The current climate crisis is fuelled by CO2 molecules released centuries ago,1 while our ongoing air pollution borrows on behalf of future generations. We live in a palimpsest woven continuously from the legacies of our ‘ongoing past’. These memories are imprinted below in the soil; when released into the air, they float into the atmosphere.

What are carbon cycles? We have abstracted live chemical processes into carbon emissions and credits, commodifying them by virtually selling them. Carbon credits work by abstracting all forms of carbon into their weights and volumes, obscuring the imbricated temporal, ecological and labour processes involved in their emissions. Carbon credits have become exercises of social calculation to continue business as usual, ignore responsibilities and live at the expense of future generations. Peatlands are the greatest planetary carbon reservoirs. Here, carbon

sequestration imprints can be traced back beyond 10,000 years. It is estimated that between one fifth and one third of Scotland’s land surface is covered in these exceptional habitats which are threatened by land use change and degradation. Historically considered to be wastelands, they have been drained for agriculture and designated for forestry. More recently, wind farms are being installed on these remote landscapes. Both afforestation and wind farms count as positive carbon credits in the market of net-zero targets. However, here is the paradox: this disturbance of peatlands releases so much carbon that it can result in negative net sums.2 Peatland degradation immediately releases into the air what thousands of years of anoxic decomposition in waterlogged soils has put into the earth.

Landscape and land-use policies shape these unique environments from the micro to the macro; from bacteria, mosses, fungi and phytoplankton to land ownership. The National Planning Framework 4 in Scotland, for example, allows the construction of wind farms on peatlands if they contribute to meet national net-zero targets.3

The following question-image pairs are a glimpse into the AA Landscape Urbanism project Re-Peat Scotland by Sara Halaoui, Ting-Yu Chao, Yu-Ting Liu and Chia-Chun Chen:

How can local communities engage with these tens-of-thousands-of-years-old soil palimpsests beyond carbon currencies, beyond neoprotectionist and new conservationist agendas?4

Engaging the senses, learning soil exploration practices and challenging the materialities of abstract carbon credits.

Soil manual pages with low-tech recognition techniques.

Soil explorations in East Schiehallion.

How can alternative soil knowledges contest land grabbing for carbon credit generation? How can these forms of engagement empower local communities?

As a critique of obscure carbon calculation apps, a manual is designed to democratise peatland knowledge for local communities.

Land tax tool proposal for Scotland.

How can we politicise carbon management practices, moving beyond problematic environmentalisms and towards land justice?

Inspired by the John Muir Trust, land management practices would be taxed for their carbon emissions, and community ownership and management would be supported through the existing Right to Buy policy.

How do carbon markets replicate exploitative Global North-South practices?

This atlas shows leaf coverage expansion in the Global South due to carbon credit plantations orchestrated by Global North institutions and markets.

All figures and photographs by Sara Halaoui, Ting-Yu Chao, Yu-Ting Liu and Chia-Chun Chen. Thank you to the AALU programme staff and to the John Muir Trust for their site visit support and feedback.

1 Andreas Malm, The Progress of This Storm: Nature and Society in a Warming World (New York: Verso, 2018).

2 Jo Smith, Dali Rani Nayak and Pete Smith, ‘Wind farms on undegraded peatlands are unlikely to reduce future carbon emissions’ in Energy Policy, no 66, March 2014, pp 585–591.

3 John Muir Trust, NPF4 Position Statement – a response from the John Muir Trust, 2021.

4 Bram Büscher and Robert Fletcher, ‘Dichotomous Natures’, in The Conservation Revolution: Radical Ideas for Saving Nature Beyond the Anthropocene (New York: Verso, 2020), pp 47–77.

Materially speaking, nothing actually disappears – at least according to scientific determinism. The laws of physics tell us that while matter cannot be created or destroyed, it can be transformed or rearranged in space. The Material Arcade focuses on materials used by students, facilitating interventions that prolong material lifespan and encourage resource circularity within the walls of the AA. The construction industry continues to consume an enormous amount of new materials (to the point of indecency) yet hesitates to embrace the reuse of them – constantly greenwashing this process and hailing recycling as a green alternative. Simply providing an alternative to landfill is rarely the best course of action and needs to be questioned: can’t we do more? For our relationship with materials to evolve, we require change-makers. We must concern ourselves with the connections between architecture and material. This concern cannot necessarily be taught, but it can be learnt. It might then evolve into a practice of care and a willingness to sacrifice some comfort for meaningful change.

The Material Arcade is a part of this learning process. What started with heaps of reusable materials left behind by past students became a repository of reclaimed materials in Diploma 18’s unit space with a focus on recirculating what is already in our system. Two years on, the Material Arcade inhabits a room in 38 Bedford Square – a process that took longer than we (and probably the AA) would like to admit. It is a room full of materials constantly circulating within the school’s walls, saved from the waste bin. The Material Arcade

shows that (some) students and staff at the AA share this common concern and are committed to making it a priority.

Do you remember riding a bicycle for the first time? Having a tight grip on the handlebars and making slight steering corrections until you felt steady? The last two years have been like that: two years of figuring out how to become – and to stay –an open resource for students and staff and an integral place within the AA. This is an urgent aspiration that requires more than a handful of passionate students. Just like acquiring a room for our material library, the push for a paid student assistant is a long and ongoing mission of ours.

The Material Arcade is a platform that is practical, instructive and collaborative. It is here to demonstrate a circular way of translating material into space. We want to remind you that while matter can neither be created nor destroyed, it can be rearranged. If we improve our processes, it can be rearranged continuously: materials can become endlessly adaptable. Shifting the paradigms of our material consumption and subverting a linear economy is not easy. Behind the Material Arcade is a community of students and staff who endeavour to see the school as a more responsible and kinder custodian of materials –and you are invited to join us!

(What to do when your objects gain consciousness and start to judge you)

‘Shrine-ing’ uses a combination of free-building, found objects and assemblage. Through the act of shrine-ing, we may start to find possibilities for new imaginative objects, spaces and feelings. The accruing shrine comes together in a final ritual, where the shrine is born and dies in the same moment. This act of ‘shrine-ing’ is a ritualised practice in three parts. First, looking at, pausing at and revelling in objects conjures something: disgust, excitement, frustration or concern. Only some of these objects make it to the second part: gathering, collecting and assembling.

Finally, the ritual of birth and death requires five people and an object sacrifice, with an entirely singular experience for the partakers and onlookers.

One day, every day, I wander through the city and wonder: where should I go? What should I do? Who should I call?

Then I see that the objects around me start to get frustrated. They pull me to one side and they say: “pause, gather, relinquish control and SHRINE.”

They whisper: “do you not know that SHRINE-ing is just like pining?”

They shout: “SHRINE-ing is a solo activity and requires only a bag and perhaps some gloves. Although that depends on the type of SHRINE you are SHRINE-ing for.”

They assert: “SHRINE-ing is nothing like mining.”

They ponder: “mind your business.”

They gripe: “follow your feet, if you want to go that way, you must! But if you think you must go that way, you mustn’t!”

Not every object can and will be taken to the next stage of SHRINE. Some cannot be paused at, some cannot be looked at, or maybe they cannot be gathered. This is still part of the process of SHRINE. That is because you thought of it, even momentarily, and the objects became part of you, not apart from them, you pined – now are you getting it?

Once I have paused at and gathered the objects, once I have relinquished control, they speak again and tell me: “we want to be put back together again.”

They squeak: “we want to find ourselves glued and tied and stuck and stacked and soldered and sat together.”

Breaking this silence, they imply: “we are not satisfied until you are not comfortable!”

Now they expect you to sacrifice one of their own. Yes! An object sacrifice! You do not argue as the ethics of the objects confuse you and you would rather revel in the new connections that have been made.

Now the objects are shushing you, hissing: “listen.”

They tremble: “not like that!”

They lament: “balance is key and do not forget that we are never dead, just asleep.”

I realise that I am getting frustrated, but at least the objects are quiet for a moment, upheld, poised in their SHRINE.

The shrine of everyday sacredness

Of everyday wakedness

And complete painstakenness welcomes you and thanks you with its presence.

And decrees that all phones shalt not buzz

Or ring

Or chime

As this is a journey of inward motion

Of complete devotion

To the thing that deeply believes

Wholeheartedly grieves And unfixedly receives

The shrine of total foresakenness

Of complete outrageousness

Of total contagiousness acknowledges and approves you recognises and spoons you gratifies, attunes to you

And asks you to do the same

By holding it up, upholding it now

And forever, amen

The shrine tells us that as you hold it

And hands find discomfort

A new disquiet subscends

And into it

A sacred beginning, a sacred end

A circle, a cycle, a cyclical friend

Not pain but feeling

Our unfettered healing

Hands hold together and Our shrine awakens

These hearts are opened

Now

Close your eyes

Don’t hold your breath

As you further into its depth

Breathe deeper

Breathe deeper pause and think

Begin now to really sink

Sense the connection

Material and real

Wood, metal, ceramic or plaster

Or perhaps, should I say rather

A stake, a stone

A gun, a bone

Hold it, grasp it

Let connection grow vaster

What you may hear Is my heart is a bell And with or without it

—Shrine Approachspeaking— me approacher! with your ego low Your spirits high And questions in tow Approach me, approacher

As you approached me before When I was ignored Abandoned, aDismembered,alone,wasted, woman scorned

Some lost whisper

A hint, a sign, a mutter

Of nothing, a flutter, a sigh a life a death and both foretold

Neither young not old

Before I was forgotten

Who sets the difference between ripe and rotten?

Now use your head

To compose a scene imagine an object

Clear and serene

One that keeps you Forever with it

And makes you half

As you make the rest

The object should fit inside a teacup as light as can carry

Ready to pluck

I ask you now Navigate your mind

Through pocket, or packet, or some such kind

Now approacher, approach me And place object within Into the teacup ...pause...

And now we pause

And perceive how we feel ...pause...

Something is felt Within the ring That reverberates out A true sense of something Can always be felt But too the silence That reverberates in As we are always with and without our things I want to show you again and again That bells and whistles, brooches and pins magnets, or gadgets or other such things Are ourselves in another form

In

To sleuth and accrue

Onward I’ll go

Now open your eyes

I thank you and ask you to reshroud the shrine And at this moment I thank you for your time

There was a collective gasp in the room when we first saw a pinch of soil from Hooke Park under the microscope. Though microscopic in size, the millions of creatures living together forced us to face the whorls of unexplored territories lying under our feet. In one glance it was evident that this underground world held secrets to rival those of the universe. We had to wonder how we had lived alongside this secret ‘micro-cosmos’ all along.

It’s funny how little we know of these creatures, despite having spent millennia trying to burrow into their domain. The microscope can only show what their world looks like, how they move and, if lucky, what they eat. Modern soil research is most often limited to

increasing agricultural yield, but the underground is capable of much more. Before the climate went into crisis, carbon emitted into the atmosphere found its way back into the soil through decomposition. Different shades of brown indicate varying quantities of carbon, the backbone of planetary life. Scientists estimate that only 10% of small soil organisms have been identified so far. In the soil, you will find a frightening number of related species that look different in size, shape and colour but appear to perform similar or unknown functions. Oribatids are a subgroup of a subgroup of our painfully common mites. They are tiny and crablike but in a handful of soil there can be a hundred different oribatid species. There are nematodes, tiny white specks to the naked eye that are revealed to be excited bugs when enlarged to 40 times their size. There are furry springtails that appear similarly excited to flee back into their comfortable environment of darkness. The smell of first rain that we all so love is caused in large part by actinomycetes bacteria. The fungi, so hard to find in urban soil samples but abundant in woodland soils, do

not thrash about like the bacteria, but carry chemical messages between trees. These messages teach forests when to hold on to their leaves, when to change colour, when to shed them and when to wake up to spring.

In the quest for grandeur in our creations, it is so easy to overlook the life we can walk over. In doing so, we overlook some of the first architects this world holds. This organised community is resilient to forces far bigger and beyond its control, and thrives in an architecture far more complicated than we will ever understand. Ecology teaches us that when you pull at one point, you tug a whole system of networks along with it. It is never possible to wholly predict how the system will respond to such interventions and aberrations. Any building we conceive of exists within the architecture of ecological systems. While humility is not often recommended for an architect, there may be lessons to be learnt from the hidden constellations of creatures quietly building and unbuilding in dark alleys within the ground. It would be in our interest to explore more intimately the soil horizons beneath our feet and around our buildings for the sake of our precarious future.

The Distant Early Warning Line –often abbreviated as the DEW Line – is a derelict system of 63 military radar stations forming a line across the 69th parallel, about 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle. It was built in a joint effort by the US and Canada during the Cold War to warn against Soviet nuclear bombers approaching over the northernmost horizon. This vast industrial presence in the Arctic landscape required enormous environmental violence, given the remoteness and hostility of the climate at the 69th parallel. 250,000 workers participated in thousands of cargo airlifts, cruises and hauls supplying materials, tools and machines required for the DEW

Line’s construction, making it one of the largest single projects1 ever undertaken by modern industry to date. It operated at the absolute limit of the imperial apparatus’s scientific and industrial ability, and required an equivalent of $23 billion in today’s rates from the US state budget to the industrial complex facilitating the conquest.

One of its longest strips cuts through the Nunavut Territory, which forms the far northern administrative region of Canada. North of Nunavut one can only find the melting ice cover of the Arctic Ocean and a seasonal array of flag posts inserted into the surface of the drifting ice. For a

glorious but brief moment, each of these once crowned the top of the earth, only to inevitably drift south. Although the area is more than eight times larger than the UK, its total population stands at just 36,000 –or 36 Architectural Associations –making it the most sparsely inhabited continuously settled territory in the world. Its desolation and immediacy to the horror of a total environmental collapse truly embody the spirit of the end of the world.

The haunting beauty of Nunavut’s landscape is damned even further by the violence of colonial crimes that it has witnessed. For thousands of years, the territory has been inhabited by several Indigenous groups. Their descendants – the Inuit – hold deep and intimate relationships to their environment.2

From the 18th century, the territory was claimed by the British who imposed imperial control; it was then transferred to Canada after the country’s formation in the second part of the century. Following a history of suffering and genocide brought on Indigenous people by these settler-colonial states, the Inuit peoples,3 who form the majority of Nunavut’s population, continually contest the Canadian authority’s presence on the land.

Through the lens of coloniality, we can define the Arctic as a frontier4, which in the North American context historically denoted a border of the territory under colonial control, separating the coloniser from the Other. The frontier denotes a limit, here enforced by the challenge that the Arctic climate imposes on the imperial industrial and technological apparatus, therefore delineating the

proverbial End of the World. Just like other territorial animals, who lay their boundary using their bodily fluids, the colonisers mark their territory with a specific architectural typology: the outpost. Here, in place of piss and shit, the frontier is delineated by watchtowers, bunkers or, in the specific context of Nunavut, radars.

In 2024, we are still pointing various technologically advanced instruments towards the north; however, they are no longer observing the hostile airspace above the frozen ocean, but the disappearance of the frozen ocean itself. Military personnel have been replaced by a community of scientists reporting on the steady disappearance of the Arctic Ocean’s ice cover. They gather around environmental research stations scattered along the edge of the polar area in a manner resembling the chain of DEW Line radars.

Despite decades of such research, we have now reached a state of irreversible damage to the climate. Those powerful enough to introduce necessary reforms fail to do so.

Norway, the Russian Federation, Canada and the United States all maintain oil and gas exploration programmes while operating most of the Arctic environmental research stations located in proximity to the offshore drilling rigs. The contradictory nature of the scientific outpost reveals a perverse detachment of policy from the image these scientific efforts allow them to project. We as subjects of this system remain petrified in the face of this violence.

In the hope of shedding some light on this issue, we will look at what these frontier architectures might tell us about the system they facilitate.

First, just like the DEW radars, the research stations are indexes5, pointing to some element in their context through their directional orientation. Just like pointing a finger may index some object in the direction of the line implied by the finger’s orientation, the scientific instruments point north to indicate their denoted object of interest as the Arctic Ocean and its melting ice cover. This is problematic in the colonial typology of an outpost. Historically, the outposts index a threat, or a danger; the DEW radars pointed toward the north index the threat of incoming Soviet bombers, placing the Arctic environment in the position historically occupied by the Other. The causality of the crisis indicated by the research stations is inverted. The melting of the ice cover is not presented as a result (or evidence) of industrially induced climate change, but as the cause of the immediate crisis.

Second, it is worthwhile to look at the distinctive architectural language

of the stations. The red and white checkerboard pattern performs its innocent purpose of increasing visibility in a whiteout. The exposed scientific instruments relentlessly collect data. Their rational form suggests a technological function. It shows the commitment of the institutions behind them to a scientific solution to the climate crisis. The stations are an expression of the pursuit of progress and trust in scientific ability, values emerging from post-Enlightenment European ideology. Scientific and technological language fragments reality into variables like weight, velocity and volume. This ‘regional ontology’ –based on algebraic principles, as Simone Weil argues in her letters and journals6 – might be too abstract and limited to represent the true nature of the dire reality. Science in its supposed neutrality has no sense of suffering, fear or pain. The alienation it triggers might explain why Othering is such an effective method of maintaining hopelessness. Technology is not just applied science – it is a type of thinking in itself. It contains our perception of reality, and actively delimits our idea of how to act upon it, therefore hindering our revolutionary ability.7

Seeing the research stations as a part of the built environment of the high Arctic provides analytical tools which reveal concerning links to other imperial projects like the DEW line. Following Audre Lorde’s principle that the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,8 we must question the interests they serve. It seems unreasonable to see their agency as separate from the imperial system from which they emerged.

Above: North American air defense systems in the mid-1960s. Right: collage by Jan Jakub Stawiarski.

Gráfico 4. Map depicting continental air defense systems. 1962. USAF Museum map.http:// pubs.aina.ucalgary.ca/aina/dewlinebib.pdf. Visitada el 04 de agosto 2015.

1 USAF DEWLine documentary, www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Mfwcp6rTjc.

2 Dalee Sambo Dorough, ‘Inuit and the Arctic environment’, www.iucncongress2020.org/newsroom/all-news/ inuit-and-arctic-environment.

Esta iniciativa profundiza y amplía sus objetivos hasta culminar en el establecimiento del Consejo Ártico el 19 de septiembre de 1996, como foro de alto nivel «para promover la cooperación, la coordinación y la interacción entre los Estados del Ártico… en temas comunes a la región, en particular las cuestiones de desarrollo sostenible y protección del medio ambiente», que se estructura en seis grupos de trabajo24 sobre la base de los temas que van a tratar.

3 Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, ‘Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Signed’, 25 May 1993, at the Wayback Machine, web.archive.org/web/20131019150055/https://www.itk.ca/historical-event/nunavut-land-claimsagreement-signed (retrieved 2 June 2023).

4 Frederick Jackson Turner, The Significance of the Frontier in American History (London: Routledge, 2011).

5 Arthur W Burks, ‘Icon, Index, and Symbol’, in Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, vol 9, no 4, June 1949, p 673.

24 http://www.arctic-council.org/index.php/en/about-us/ working-groups/114-resources/about/wor king-groups:

6 Simone Weil, ‘The Needs of The Soul’, in SimoneWeil:AnAnthology, edited by Sian Miles (London: Penguin, 2005), p 106.

– Arctic Contaminants Action Program (ACAP).

– Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP).

7 ‘Heidegger and Technology’, from Continental Philosophy, podcast, 5 April 2022, shows.acast.com/ transcendence-and-the-body/episodes/lecture-10-heidegger-and-technology.

– Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF).

8 Audre Lorde, ‘The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House’, 1984, in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 2007), pp 110–114.

– Emergency Prevention, Preparedness and Response (EPPR).

– Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment (PAME).

– Sustainable Development Working Group (SDWG).

आसन [Aah-sun] is the still posture or the seat in moving meditation, and the word used for the dedicated seat of Lord Ganesha during the Hindu festival of Ganesh Chaturthi. In English, it is an altar of sorts which honours the embodiment of ritual.

The ceremony, स्थापना [sthah-pana], takes place on the first day, before which the dedicated आसन is created with specific objects that await the idol to accompany the ceremony. The overall act becomes a ritual. The placement of these objects is a deliberate act, informed by the specific movements which perform the ceremony.

In the context of the festival, diasporic identity is manifested within the ceremonial objects placed in the आसन: they exist as the tangible presence of memories. Decorations form both a static backdrop and a means of preserving the ‘native’ identity. The diasporic condition calls for a reinterpretation of ritual. How can this become a community activity to reimagine and activate static traditions?

The brick altar spatially reimagines the ritual, acting as the structural backdrop to host the ceremony. The clay pieces are vessels that are informed by the bricks to hold the ritual objects. They become the designer’s way of reinterpreting the ritual.

As the clay vessels dry and converse with the fired clay bricks, they become an active form of the piece. They give shape to the ritual through their own agency; these are vessels ‘that come from tradition but speak in a contemporary language’. This performative altar provokes the question: what is the active archive of diaspora?

Chisei

Chisei

In a Japanese household, one might discover an elaborately decorated cabinet in a wall niche. This cabinet is called Butsudan, an ancestral altar that is deeply affiliated with the Buddhist tradition.

What is the appeal of the Butsudan in an increasingly secularised society? An examination of the structure of the Butsudan is warranted. The altar is usually made of mahogany; at its centre lies a golden Buddhist statue, flanked by tablets inscribed with the names of ancestors. In front of these objects are candles, incense and various offerings. The ways

these artefacts interact with the user form a meticulously choreographed act that facilitates the veneration process. Through the generational practice of these prescribed rituals, a portal opens, connecting the living to the dead.

Examining the form and meaning of the Butsudan, one is reminded of a similar typology: the Buddhist temple itself. Butsudan can be thought of as a miniature temple, a complex cosmological space atomised and moved into a domestic space. However, the Butsudan is not simply a reminder of religious links.

Traditionally, Japanese settlements are developed with the temple at their centre. Charged by communal activities such as festivals and celebrations, temples are imbued with agency for social cohesion. The Butsudan is thus not only a mnemonic device that ignites the past, but also a knowledge system that alludes to connections with one’s contemporaries.

In an increasingly alienating world where one is often uprooted from one's origins and isolated by the doctrines of a society regulated by economic efficiency, people strive for connection. Akin to the Aah-sun's ability to activate one’s identity amid the vicissitudes of diasporic drift, here lies the inherent power of the Butsudan. Rising from the earth and the soil, it punctures the linearity of time, weaving together the living and the dead; at the same time, it reminds us of the interconnected and situated reality of our lives.

The AA Low Carbon Project tackles the challenging task of quantifying the AA’s annual carbon footprint, a necessary part of a sustainable approach to architecture. It serves as a practical and insightful exercise, offering a transparent snapshot of our environmental impact.

Measuring the carbon footprint of the AA is no small feat, requiring meticulous data collection through checking records, surveys of students and staff and a thorough analysis of our buildings. It establishes a baseline of the current state of affairs, all the activities we do and their impacts. It becomes a pragmatic tool for initiating conversations within the architectural community about the need for carbon reduction strategies.

The project is not just about numbers; it's a call to action. By identifying areas of high carbon emissions, it sets the stage for constructive discussions on how to minimise environmental impact. It becomes a roadmap for devising and implementing practical solutions, fostering a culture of sustainability within the AA. Moving forward, we intend to create open discussions with experts such as Mike Berners-Lee and organisations such as Bennet Associates and the Greater London Authority (GLA) who are already on the journey to reduce carbon emissions. We also plan to publish our findings in a journal article to build on knowledge in this area.

Looking ahead to 2030, this project may be viewed as a crucial turning point. The insights gained and the strategies developed could become ingrained in the daily practices of our architectural community. Rather than a grandiose narrative, the significance lies in the practical impact – a gradual shift towards more environmentally conscious design and decision-making, demonstrating a commitment to a low carbon future.

Visit lowcarbon.aaschool.ac.uk to find out more about the project.

Protected by this ‘magic attractive idea’ of designing with natural colours the lighting of a performance, of a concert, of a ballet by using only full moon light, we were able to open a wider field of research and investigations for the use of minimal natural light. In doing so we were also shaking the roots of theatre itself in a forgotten environment. The ‘Wonderful Laboratory’ was born.

-Humbert Camerlo-The Full-Moon Theatre is a project of many lifetimes.

-Peter Rice-More than 30 years ago, an international team of physicists, engineers, artists, musicians, writers, choreographers, dancers, film directors and television producers set out to create the first open air theatre performance illuminated exclusively by the light of the moon.

The project started in 1987 in the opera director Humbert Camerlo’s summer residence, located in a remote valley in the south of France. Humbert’s design team included the engineer Peter Rice, famous for his structural design of Centre Pompidou, and other engineers from Arup and RFR, in particular Andy Sedgwick and Nicolas Prouvé, who worked on the moon path calculations and on the designs for moonlight reflectors.

A team of stonemasons from the Atlas mountains in Morocco built the theatre over a period of eight weeks. A local workshop was also established to fabricate different types of moonlight reflectors. Each reflector type was given the name of an astronomer, such as Copernicus, Kepler and Archimedes.

The ethos of the project was to slowly build local expertise, creating a learning process in which there is no passive spectator but instead everyone is an active participant. It is also a spiritual experience, reconnecting participants to the primordial relationship with moonlight.

In 1991, the first performance took place during the full moon in June. In August, a five-hour TV special with a dance performance by Momix was broadcast from the theatre to coincide with a lunar eclipse. The following year, new larger reflectors were developed, each one named after the stars: Antares, Pollux, Altair, Vega, Deneb and Polaris.

Additional performances were planned on moonlit nights the year after but were not realised due to a lack of financial support. In the following decades, more attempts were made to refine the project and stage performances.

Peter Rice said of the endeavour that: ‘All that we can hope is that other people will be stimulated by it and will not just copy us but find their own place and their problems, their myths, their breath. Eventually one could imagine a dozen locations around the world where there would be moon theatres, all completely different but generated by some reservoir of enthusiasm linked at a spiritual level. Gourgoubès will eventually become my spiritual home, that part of me which is not in Ireland. The Full Moon Theatre is a project which is just beginning.’

I discovered this marvellous project when I read Peter Rice’s book An Engineer Imagines (1994) while studying at university. The Full Moon Theatre is the last described in the publication and was indeed the last that Rice worked on before his premature death.

After university, I joined the engineering firm Arup and in 2012 became involved in the exhibition Traces of Peter Rice to celebrate Rice’s extraordinary life and work. The opening of the exhibition was an opportunity to meet Humbert Camerlo. His enthusiasm for the Full Moon Theatre was highly contagious and I soon found myself involved in meetings to plan Full Moon Theatres around the world.

Camerlo’s death in 2020 came as a shock to the communities of art, science, technology and moonlight lovers that he had nurtured. I realised that he had inspired in all the people that he encountered a passion for beauty, community and design that is respectful to nature. However, very little technical information remained for new generations to take on his and Rice’s legacy. The AA Visiting School

programme, supported by the Arup Phase 2 cultural programme, provided me with the opportunity to restart this project and to lay the foundations for the laboratory to continue, as well as to optimise its tools and reflector designs, enabling more Full Moon Theatres around the world to begin flourishing.

The laboratory took place in Hooke Park over the course of four days between 4–7 March 2023, with the last night being a full moon.

The intentions of the visiting school were 1) to incorporate and develop existing research to design and construct a site-specific open air Full Moon Theatre, equipped with locally digitally fabricated moonlight reflectors; 2) to stage a test performance fully illuminated by the light of the moon, without using electricity; and 3) to create an online ‘Full Moon Library’ including all the tools, documentation and techniques developed during the workshop that anyone can use to stage a Full Moon Theatre performance anywhere in the world.

The workshop demonstrated that it is possible to create with economy of means, being sensitive to the local context and constraints. We produced everything on site, this time combining manual techniques with new digital fabrication and simulation tools. In doing so we took the original concept one step further, bringing new experimentation and innovation to the processes and making the knowledge base available for future use.

A new workshop is planned for early spring, between 22–25 March 2024:

www.aaschool.ac.uk/academicprogrammes/ visitingschool/full-moon-theatre

The design materials developed during the workshop are available online, and include a new parametric reflector design and digital calculation tools to facilitate event planning and lighting simulation to validate how the reflectors work on any specific site: fullmoontheatre.org/ github.com/fullmoontheatre

You are invited to browse through these resources, study them, improve them and use them to create your own Full Moon Theatre anywhere you wish.

By manipulating existing materials, we weave everyday life into domestic space. In this case study, I take the DIY modifications of old residences in Suzhou, China as an extreme example to unfold how we, as human beings with psycho-physical needs, dwell on the earth.

The DIY modifications are not designed intentionally, nor are they careless or naïve. Designer Jane Futon Suri used the term ‘intuitive design’ to describe thoughtless acts: how we intuitively adapt, exploit and react to our environment.1 From the users’ perspective, Michel de Certeau argues that everyday life works by a process of poaching on the territory of others, using rules and products that already exist in a way that is influenced but never wholly determined by those rules and products.2 In these old residences, occupants play with the existing structure by manipulating building components and ready-made materials to better adapt to the traditional building structure.

For instance, any building component can serve as a tool board for housework. Inhabitants take advantage of the shape and material of building components to set these up. The round shape of a column increases the available surface: nails are used to hang brushes from wood columns, hooks are used to hang buckets from brick columns and wires are twisted around columns to set up a socket. On the wall, there are hooks for hanging mops, lights and mailboxes. Additionally, the wall serves as a billboard for people to broadcast information including forms of address, custom, self-expression, warning and willingness.

Pipes and wires follow the form of the building or fit through the patterns of a wooden panel without destroying it. In unnoticed corners and untouchable areas, wires intersect and become a mess. On the façade, wires and pipes behave well so that they don’t affect daily activities and the appearance of the building. In ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, Walter Benjamin said that reproductive technology shortened the distance between the contemporary masses and the aura of the original object. The unique sense of the aura is evenly spread out and becomes less exciting.3 However, I would argue that in these old residences, the transformed products and materials favourably reproduce the aura derived from an original piece of work.

Clothes-hanging techniques show how occupants create joinery using existing materials and utilise void space. To hang clothes in a hallway, one way is to put bamboo between two door frames or columns by taking advantage of decorative elements. Another method is to hammer two hooks into opposite walls and use rope to connect them.

A metal frame for clothes hangers can be attached to wooden handrails. With basic elements – hook, rope and bamboo – a cozy place for hanging clothes is created. This exhibition of clothes creates a silent but warm communication between neighbourhoods.

Today, people seem to be spoiled by the shopping centre. When you need a table, for instance, you can easily choose by function, placement, price, shape and size. These choices are confined to the given range of mass-produced objects, exacerbating the stereotype of the ‘ideal home’.4 The interactions between occupants and buildings recorded here are not a result of a lack of resources but an escape from commercial markets. Their design and the way they are made demonstrate how the built environment might be altered, their histories lodged in various surfaces and media. This is a practice of adaptive reuse, dissolving the boundary between designing and making. Through the phenomenon of temporary and adaptable modifications, what is left surrounding us is the accumulation of signs that point to the authenticity of every moment we live.

1 Jane Fulton Suri, Thoughtless Acts?: Observations on Intuitive Design (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2005).

2 Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984).

3 Walter Benjamin, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, 1935.

4 A Fu, ‘Orders of Life’ in DEMO, no 5, June 2021, pp 44–79.

Caterpillar serum: many insecticides and pesticides can cause a caterpillar to spit or vomit bright green. This green fluid is similar in colour to a caterpillar’s hemolymph (blood). To identify the difference, remember that hemolymph dries to a dark color, nearly black, in less than five minutes.

Rat hat: rats remember which humans have tickled and played with them in the past and prefer to spend time with those people. Rat ‘laughter’ is a very high-pitched squeak. They spend several hours a day cleaning themselves and cleaning others as a form of social bonding.

Monkeys see and Monkeys do

Just like you and I do too

It all began in hardwood Crowns Deep within the Forest

We evolved and built our Homes And took our Beauty from it

To Gods we prayed and Death we nayed Beneath our Trees beloveth

Then we evolved and burnt our Homes As Modern Men all do And Kings of Oak and Beech were gone With them our Beauty too

Then we evolved as Monkeys do And all we knew was lost

Until the eyes of me and you Put Fire to the Frost

And now we see again, again

A Renaissance of Crowns Of Kings and Queens of Ash and Elm And Science even bows

What is the World if not the Trees

Are we our Nature’s cancer? If question begs to save the World Then Truth is not the answer

For we need more to Birth the Life Of Anciency, which made us And Truth is but a means my friend, Beauty is the end.

American photographer Ansel Adams spent a lifetime photographing California’s Yosemite National Park. In 1949, he captured his iconic photo of the Yosemite Valley, Thunderstorms. A classically sublime landscape, it strikes in equal parts awe and desire. It is an image of nature that Adams constructed, for, in his own words, ‘You don’t take a photograph, you make it’.

Adams and his fellow photographers and painters of the National Parks didn’t only make images: they helped to construct the very notion of wilderness. When viewing their work, what they show is just as important. What happens if we expand the visual frame? Expanding the frame exposes it as a construct, a fantasy of the natural realm with violent consequences.

The construction of wilderness.

For the frame, by curating a fixed scene, exists through omission, displacing those not desired by the pictorial gaze. Adams was aware of Indigenous Miwuk peoples who had lived in the Ahwahnee valley – so-called Yosemite – for millennia. He deliberately chose to turn his camera away. Paradoxically, the same men who campaigned for nature preservation, mourning the loss of pristine nature in the rapidly industrialising urban centres where they lived, were also the ones benefitting most from colonial modernity. This reverence for the sublime was a European import, rooted in Romantic categorisations of landscape.

The 19th century European Romantic movement categorised landscape as the sublime, the picturesque and the pastoral. These imaginaries became key to the colonial project of terraforming, where conquered landscapes transformed into neo-Europes. In the United States, pre-colonial land was perceived as an entirely wild – and sublime – terra nullius. As land was seized, divided and rendered property, productive pastoral landscapes emerged, transplanted from the English countryside to create rural America.

American national parks are perhaps the last visible remnants of the colonial frontier, an effort to maintain some of the uncharted territory of early colonisation. Here lies a paradox of the wilderness: while the sublime implies a certain degree of humility, with humans at the mercy of magisterial nature, the wilderness park encloses sublimity, containing the uncontainable within legislated boundaries. This paradox exposes wilderness as an ideal, closer to morality than reality.

When the image meets the landscape.

A landscape image is propositional, a device by which a particular framing of landscape is disseminated. Photographs of Yosemite as wilderness influenced campaigners like John Muir, known as the father of the National Parks. In 1890, an Act of Congress officially designated Yosemite a National Park. Nearly a century later, in 1964, the Wilderness Act was instituted, formalising wilderness as ‘an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man’.

Views in Yosemite.

Romantic artists were similarly key to the conservation of land in the UK. Poet William Wordsworth called for the preservation of scenic landscapes as ‘a sort of national property’. The notion of property ownership is central to conservationism, highlighting a contrast between British national parks, which are primarily privately owned, and American ones, which are publicly owned. These differing ownership strategies emerged from two border regimes: the frontier on one hand, and enclosure of the commons on the other.

In the National Parks of England, we see the wild and the pastoral merge. The Peak District, designated in 1951 as England’s first National Park, is made up of a patchwork of privately-owned pastures. Public access to them was not a given; it was fought for, such as in the Kinder Scout mass trespass in 1932.

Romantic-era landscape paintings of Derbyshire created an illusion of far-reaching landscapes, masking the reality of enclosure and privatisation. The English National Park attempts to reinstate access without the commons, where conservation becomes an authoritative blanket over a privatised landscape. England’s conservation efforts centre the notion of ‘landscape value’, often involving a combination of scenic, economic and cultural factors, and defined by clear boundaries.

While Yosemite seeks to shield wilderness from human impact, the Peak District recognises inevitable human transformation as worthy of preservation. Where both converge is in asserting control through clear conservation boundaries: protected land always exists in opposition to the unprotected. But who draws these boundaries? Are only scenic landscapes worth saving from unregulated environmental devastation?

If we are to take seriously western conservation’s colonial legacy, reject the human-nature dichotomy and refuse the commodification of land and life, this will radically reshape the meaning of conservation in terms of both representations of and relationships to the land. What happens when the frame becomes a mirror, and we recognise the wilderness within ourselves?

Images: [1] A Tale of a Scrap Ruby , live performance, AA school [2] The Transformative Landscape , live performance, Epping Forest [3] The Undefined Landscape , live performance, Uffington White Horse [4] Earth Transformation , live performance, AA school

Performers: Mediator –Yuchen Wu

Resident –Mathias Sagvik

Protector –Beatriz Marco Sánchez-Peral

Extractor –Emmanuel Reynier

Music: Xuanni Photo taken by Amalia Pantazopoulou and Violet Yue Cao.

Who owns the land we live on?

What are we seeking in the land?

Where is your home? Where are your ancestors? Are you an extractor? Are you a protector? You are in the conversation now, What is your next move?

Where Lakeshore meets Leslie lies Toronto’s greatest accident. Today we call this Tommy Thompson Park, but let us not mistake the site for what it truly is. Spilling 5km into Lake Ontario is Old Toronto. Smoothed by the waves, Old Toronto is slowly reducing to sand, clay and ore. In time, however, new life has come from this monumental death. Like a less deliberate Freshkills glow-up, Tommy Thompson Park has become a sanctuary for wildlife, leaving historians to puzzle over the definition of ‘urban heritage’.

One can only laugh at the irony in all of this: a trash heap haven? A refuse refuge? Architects have been obsessed with utopia as long as the idea has existed. Now, to design utopia is to say: ‘my building is better off dead!’ In the vein of futurism, let us realise this utopia in a single evening. Like a scene from a doomsday thriller, it might go something like this:

In moonless black I awake to a maddening orchestra of destruction. A violent quiver consumes the earth.

Concrete and stone, like sticks, split and crumble. Glass shards seeking sweet cessation smooth, becoming beads in flight. Tile and trim torpedo into trees and till the soil. Clay turns to brick and back to clay. The pulsing snap of splintering steel is total. Only terror is tangible in that two-dimensional darkness. Somewhere beyond the pitch a great shadow bows and sinks into the horizon. A building falls. No tears are shed for it (someone’s getting richer).

In days’ time, it cannot be said to have existed. Love did not create it and surely won’t revive it. Dead and buried in the same stuff that was heated, poured and pounded to form it. A mound is what’s left. Only Loos would call that architecture. Only Marinetti would call that progress. There is no heaven for buildings, only purgatory. A skyline is a graveyard. Forgotten, destined to rot, rust and wither. Slow decay is the history of architecture. Let us champion corrosion! Rejoice in rubble! Dine in debris!

Oh, the horror! Like Nero’s Rome, Tommy Thompson Park could be built in a day, but only the crazed would entertain it. Only once the glass shards lost their cut could Tommy Thompson Park enjoy its successes. You see now: decay testifies more convincingly than destruction. No? Then take Pruitt-Igoe. Although some would argue modernism died in the blast, it was already dead when the first brick was laid, but only through decay could architects, planners and politicians accept that reality.

I’m not convinced by your shiny plaque. Show me the decomposition report and we’ll talk.

LEED certification is still corporate greenwashing.

A building cannot biodegrade. A building is an erection of mined resources.

A building is plastic.

A building is blight.

A building is waste.

The passive house is exactly that: passive. It’s a hermetically sealed envelope; a perfectly conditioned environment from which to watch the world burn. Would we not care more for the environment if we actually felt it? In downtown Toronto, you can live in a condo, take the elevator down to the Path system, walk in an air conditioned mall and ascend to your place of work. You never have to feel the effects of climate change, therefore you can blissfully deny its existence. Refab is an open window. Refab is smelling urbanism and its consequences.

Waste does not exist in nature. Everything that grows eventually decomposes so new life can flourish. We are from nature but like a spoiled child we take and take from it. We consume and dispose, enjoying a few moments’ relief from our insatiable capitalist appetite before engorging ourselves on the next commodity. Like monarchs we build our spires of refuse so we can stare down on those with ‘less’. When the ground disappears, we might think ourselves almighty, but it is we who will suffer the greatest loss. Rampant consumption estranges our natural selves.

The global citizen produces 0.74kg of waste per day1, yet few have experienced a landfill. Half of the earth’s population already believes in resurrection, yet few have seen it happen.2 Like a landfill, to say you have not seen a resurrection is not to say it does not exist. After all, refabrication is resurrection. Show me a nonbeliever, I’ll show you a miracle! Wielded by the conscientious designer, refab is the release of agency. Like Jean Arp watching paper scraps fall, it is succumbing to chance. Today, we might build with these scraps. But we must do so urgently and thoughtfully. Unlike waste, we have limited time. Plastic is the first renewable resource of the Anthropocene. Wind, solar and hydro have always been there, but we created waste, and now it is a part of us. We have enough of it floating in the ocean to build Atlantis. So why not build our cities from it?

Building is humanity’s pitiful vocation. We dig pits then fill them in. Build towers then watch them fall. Our incessant desire to impress form upon nature leads nowhere. What compels us? Is it insecurity? A dying retort to our obsolete existence? Buildings are mausoleums: timeless tombs of wealth and self-indulgence. The deluded architect is drunk on power, on visions of immortality. Surely architecture can be more selfaware. Your render is not immutable. It’s not even real! Refab is the new rehab. Sober up!

Alas, we who believe in refab needn’t overcomplicate the world’s predicament. It is obvious and simple, and so too are our demands:

1. Begin with found material. Trash is bountiful. Refuse is opportunity.

2. Create nothing new. Breathe life into forgotten objects.

3. Design for deconstruction. Every building, every object and every material has use in its afterlife.

4. Repair, don’t restart. Decay does not warrant destruction.

5. Don’t force it.

Patina and decay are nature’s painting and sculpture. No human could master them.

6. Let our walls accumulate the trace marks of their occupants. Resist erasure!

Let the scarred and scraped walls tell an honest history.

7. Slow down.

Decelerate consumption. Longevity means taking little, and taking nothing for granted.

The Refab Manifesto was originally written in 2021 and is published here for the first time.

Francesco Anselmo

Francesco is an ETS lecturer and tutor. He has studied architectural engineering and lighting design and holds a PhD in building physics.

Giles Bruce, Cíaran Malik, Tom Raymont and Sal Wilson

Cíaran, Giles, Tom and Sal are all ETS Tutors at the AA. Cíaran’s research is interested in whole life carbon in design and Giles, Tom and Sal’s work looks at the balance of low carbon approaches to environmental comfort.

Fergus Egan

Fergus is a Diploma student and a member of the Material Arcade. He is interested in how architecture can be a tool for social change.

Thomas Germain-Pendry

Thomas is a Diploma student. Their practice uses sensuality to unravel relationships between identity, behaviour and space.

Leela Keshav

Leela is a Diploma student and an editor of AArchitecture. Her current work imagines ‘nature’ after conservation, shaped by dreams of abolitionist and reparative futures.

Julia Lubner

Julia is a Diploma student. Before architecture, she studied philosophy and wanted to be a teacher. Her current work uses assemblage as a way to imbue everyday objects with sacredness.

Reshma Susan Mathew

Reshma is a postgraduate student on the AA Landscape Urbanism programme. She is interested in exploring stories of how landscape shapes communities.

Mio Marius del Negro

Mio is an Intermediate student focused on the intersection of humans and nature in the Anthropocene, with a particular interest in biomimetics.

Jay Potts

Jay is a Diploma student and an editor of AArchitecture. His work focuses on material reuse, maintenance and self-building to form resilient communities through care and mutual aid.

José Alfredo Ramírez Galindo

José is co-head of the AA's Ground Lab, head of the AA Landscape Urbanism programme and head of the Mexico Visiting School at the AA.

Clara Olóriz Sanjuán

Clara is a researcher, tutor and practicing architect. She teaches on the AA Landscape Urbanism programme.

Sharvaree Shirode

Sharvaree is a Diploma student. She is interested in spatial reinterpretations of rituals through a diasporic lens and how these become vessels for rituals to manifest in public space.

Jan Jakub Stawiarski

Jan is a mixed-media artist and an AA Diploma graduate. He is critical of the impact that technology has on our lives.

Elena Luciano Suastegui

Elena is a landscape urbanist and earth scientist. She teaches on the AA Landscape Urbanism programme.

Peder Andreas Sveen

Peder is a Diploma student. Since joining the AA, he has explored the sculptural and structural qualities of objects of nature, especially trees.

Hafsa Syed

Hafsa is a Diploma student, interested in challenging human-centric worldviews by visualing encounters with more-than-human entities.

Monzie Tan

Monzie is a Diploma student. She sporadically blogs about material cultures and objects from around the world.

Jiayi Wang

Jiayi is a PhD student at the AA. She previously studied product design and int interests lie in adaptive reuse and narratives of everyday life.

Tatiana Watrelot

Tatiana is a Diploma student and an editor of AArchitecture, and is interested in exploring the organic movement of the body in space.

Charlotte Wesselmann

Charlotte is a Diploma student and a core member of the Material Arcade. She strives to foster the built environment’s transition to circular economies.

James Westcott

James co-teaches Diploma 18, a unit based on material flows, and recently edited a book with Rotor called Ad Hoc Baroque

Chisei Ye

Chisei is a Diploma student. He is interested in the role of festival forms in Japan in relation to the aftermath of tsunamis and the imposition of state infrastructure that followed.

Violet Yue Cao

Violet is a Diploma student at the AA. Her work is currently interested in socio-material choreography, theatre-making and performance.

AArchitecture 46

Term 1–2, 2023–24

www.aaschool.ac.uk

Student Editorial Team: Leela Keshav

Jay Potts

Tatiana Watrelot

Editorial Board:

Alex Lorente, Membership

Ryan Dillon, AA Communications Studio

Manijeh Verghese, Public Engagement

Design and Editorial Support: Caspar Bailey, Andrew Reid and Max Zarzycki, AA Communications Studio

Printed by Blackmore, England

Published by the Architectural Association

36 Bedford Square

London WC1B 3ES

Architectural Association (Inc)

Registered Charity No 311083

Company limited by guarantee

Registered in England No 171402

Registered office as above

© 2024 All rights reserved.