BIRDCONSERVATION

SPRING

The Magazine of American Bird Conservancy

2023

ABC is dedicated to conserving wild birds and their habitats throughout the Americas. With an emphasis on achieving results and working in partnership, we take on the greatest threats facing birds today, innovating and building on rapid advancements in science to halt extinctions, protect habitats, eliminate threats, and build capacity for bird conservation. abcbirds.org

A copy of the current financial statement and registration filed by the organization may be obtained by contacting: ABC, P.O. Box 249, The Plains, VA 20198. 540-253-5780, or by contacting the following state agencies:

Florida: Division of Consumer Services, toll-free number within the state: 800-435-7352.

Maryland: For the cost of copies and postage: Office of the Secretary of State, Statehouse, Annapolis, MD 21401.

New Jersey: Attorney General, State of New Jersey: 201-504-6259.

New York: Office of the Attorney General, Department of Law, Charities Bureau, 120 Broadway, New York, NY 10271.

Pennsylvania: Department of State, toll-free number within the state: 800-732-0999.

Virginia: State Division of Consumer Affairs, Dept. of Agriculture and Consumer Services, P.O. Box 1163, Richmond, VA 23209.

West Virginia: Secretary of State, State Capitol, Charleston, WV 25305.

Registration does not imply endorsement, approval, or recommendation by any state.

Bird Conservation is the member magazine of ABC and is published three times yearly.

Senior Editor: Howard Youth

VP of Communications: Clare Nielsen

Graphic Design: Gemma Radko

Contributors: Erin Chen, Chris Farmer, Eliana Fierro-Calderón, Rachel Fritts, Lewis Grove, Bennett Hennessey, Steve Holmer, Brad Keitt, Hardy Kern, Daniel J. Lebbin, Sea McKeon, John C. Mittermeier, Jack Morrison, Michael J. Parr, Marcelo Tognelli, Amy Upgren, George E. Wallace, David A. Wiedenfeld, Kelly Wood

For more information contact:

American Bird Conservancy P.O. Box 249 The Plains, VA 20198 540-253-5780 • info@abcbirds.org

ABC is proud to be a BirdLife Partner

Find us on social!

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FEATURES

Demystifying North America’s Off-the-Grid Rosy-Finches

Tough Alpine Songbirds and Questions of Climate

p. 14

Birds Mean Business in Ecuador’s Andes

The Marvels of Mindo p 24

Dawn Songs

For Birds and Humanity, a United, Diverse Voice p. 30

Toucan Barbet by Mike Parr

DEPARTMENTS

BIRD’S EYE VIEW

Hopes for Habitat p. 4

ON THE WIRE p. 6

BIRDS IN BRIEF p. 12

ABC BIRDING

Palila Forest Discovery Trail, Hawai'i p. 20

BIRD HERO

From Sand Miner to Community Conservationist p. 34

3 BIRD CONSERVATION | SPRING 2023

COVER: The Velvet-purple Coronet is one of dozens of Chocó ecoregion endemics found in Ecuador's Mindo Region. Learn more on p. 24. Photo by Owen Deutsch, www.owendeutsch.com.

LEFT: Mourning Warbler by Joshua Galicki. This species is highly susceptible to window collisions during migration, especially with lowrise buildings. ABC BirdTape can help prevent bird strikes; see p. 8.

Spring 2023 20 30

14

Palila by Robby Kohley

24

Yellow Warbler by Matthew Jolley, Shutterstock

Gray-crowned Rosy-Finch by

Eivor Kuchta, Shutterstock

4 BIRD’S EYE VIEW BIRD CONSERVATION | SPRING 2023

CONSERVING HABITAT,

for the Love of Birds

by Michael J. Parr

Ilove birding. It is an escape from the predictability of everyday life, and provides me with a connection to the natural world that is primordially satisfying. It is at once a meditation and a sport, and a way to see the world through a lens that makes a direct connection to nature. It is the closest thing to a religion that I have, having been raised by humanist parents.

When I moved to live in the U.S. permanently in 1993, I set myself a goal of seeing every bird species regularly found here. Today, 30 years later, I have around 30 species to go to reach my goal. On my most recent trip to southern Arizona, I was struck by an interesting realization: Very few of the more than 700 bird species I have now seen in the U.S. required much of a longdistance hike. I haven’t had to camp in the wilderness much; I haven’t had to walk hundreds of miles carrying all my food and water. In fact, so many of the species I have seen have been within a few hundred yards of where I was able to park my car. Among the most recent additions were a Greater Pewee in a crowded Tucson city park, a Whiskered Screech-Owl only feet from an outdoor amphitheater in Madera Canyon, a flock of Chihuahuan Meadowlarks in a grazed field next to a new subdivision, and a Violet-crowned Hummingbird at a feeder at the Paton Center for Hummingbirds in Patagonia.

I’ve reflected on this and concluded that birds and people can easily coexist — but what birds need most is appropriate well-managed habitat. That pewee only needed some trees to perch in for its sallies to catch insects — and the insects themselves, of course. The owl needed high-altitude oak forest, of which there is an abundance in Madera Canyon — it didn’t seem to mind

that a few square yards had been adapted for music and other community activities.

The fact that so many habitats have been adapted for human use, but are otherwise well-managed for wildlife gives me hope that we can still provide a place for birds in the future — even as climate changes and development continue to alter the planet, mindful habitat management for birds can make all the difference between whether we have birds and other wildlife in the future or not.

It is this habitat management that ABC focuses its efforts on, whether that habitat is in a subdivision in Arizona that could be impacted by free-roaming cats, on the remote slopes of an Andean volcano suffering from deforestation, or even in the air column that birds use during migrations that can be interrupted by poorly sited wind turbines and glass windows. ABC is all about habitat, and that’s what I believe birds need most in this human-influenced world — which offers both perils and sanctuary to them. It really depends on us.

More good bird habitat is the answer. Thank you for supporting ABC in our work to provide it.

5 BIRD CONSERVATION | SPRING 2023

Michael J. Parr, President American Bird Conservancy

TOP LEFT: Violet-crowned Hummingbird by Owen Deutsch, www.owendeutsch.com. TOP RIGHT: Greater Pewee by Robert Royse.

LEFT: Whiskered Screech-Owl by Amanda Guercio, Shutterstock

Parakeet "Boxes" Its Way Back

Once on the ropes, Brazil’s colorful Gray-breasted Parakeet is making a comeback, thanks to dedicated partners, communities, habitat protection — and nest boxes. The latest milestone in this rebound occurred in February, when three wildhatched Gray-breasted Parakeets took flight in a private reserve in the Aratanha Mountains in eastern Brazil — likely the first fledglings of this species in this location in decades.

Following many years of habitat loss and capture for the cage bird trade, the Gray-breasted Parakeet hovered close to extinction in 2009, when the Brazilian conservation organization Aquasis began working in the Baturité Mountains to save the last-known group of wild birds. Part of the strategy: installing specially designed nest boxes that accommodate family groups of the birds.

The project has been a great success and example for other efforts to save rare parrots. By 2022, nearly 2,500 Gray-breasted Parakeets had fledged from nest boxes placed by Aquasis with the support of Loro Parque Foundation. The species was downlisted in 2017 from Critically Endangered to Endangered, thanks in good part to these efforts.

With ABC support, Aquasis also launched an education campaign aimed at tackling the poaching issue and

instilling community pride in this unique bird. As a result, the threat of poaching has now been reduced. ABC also supported reintroduction efforts including the Aquasis team’s construction of an aviary that serves as an acclimation area for the relocated birds, before their release.

The Aratanha Mountains site, about 35 miles northeast of the Baturité Mountains, is the first of five areas identified by Aquasis for reintroductions of this species. The team is encouraged after this success. “This is possibly the first planned translocation of an endangered species in Brazil, and we are happy to be part of this story,” says Fabio Nunes, Gray-breasted Parakeet Project Coordinator for Aquasis. “For the Gray-breasted Parakeet, it is one more step away from extinction.”

See the birds and people behind this project at: bit.ly/GBParakeet

ABC thanks David and Patricia Davidson, George Powell, and the Pat Palmer Foundation for their major support of this work.

New Reserve Provides Habitat and Hope for a Desert-nesting Seabird

ABC

and its Chilean conservation partner Red de Observadores de Aves y Vida Silvestre de Chile (ROC) announced in January establishment of a community reserve that protects the largest-known breeding colony of the Markham’s Storm-Petrel. This follows years of effort by ROC and financial support from ABC since 2016. It is the first-ever reserve set up to protect a breeding site of this species.

“This is something we are very happy about, finalizing something that we have been working on for some years,” says Ivo Tejeda, the Executive Director of ROC.

The new community reserve, located in northern Chile, encompasses more than 1,600 acres that support a

20,000-pair Markham’s Storm-Petrel colony known as Pampa Chaca. Previously, the colony was on public land, where it was at risk from mining and energy projects, as well as military activities. Now, the government has transferred the land to ROC through a five-year concession to manage it specifically for conservation purposes.

Until recently, researchers knew very little about the breeding habits of this small, dark seabird with lead-gray wing patches, due to its unusual breeding habits. It turns out that, like several other storm-petrels seen off the coast of Peru and Chile, the species prefers to nest in the Atacama Desert, frequently under saltpeter deposits more than 10 miles inland, in a landscape so barren it resembles the surface of Mars.

continued on p.8

BIRD CONSERVATION | SPRING 2023 6

ON the WIRE

Gray-breasted Parakeet by Aquasis

Lost Birds, Found!

You can’t prevent a bird’s extinction if you don’t know where it is. The Search for Lost Birds, a partnership between Re:wild, ABC, eBird, and BirdLife International, aims to find lost bird species, and has been hitting its targets! Here are the most recent rediscoveries:

Madagascar: Dusky Tetraka

This small olive-colored and yellow-throated bird eluded ornithologists for 24 years (1999), until it was rediscovered by an expedition team, led by The Peregrine Fund’s Madagascar Program, in two different remote sites in tropical forests of northeastern Madagascar, in late December 2022 and in January this year. ABC’s Director of the Search for Lost Birds program John C. Mittermeier was part of the team that found this bird.

first collected in 1946. Since this rediscovery, with ABC support, a project by Colombian NGO SELVA has documented the species consistently.

And a miss:

In March, a second expedition to seek the Sinu Parakeet, launched by the Sociedad Ornitológica de Córdoba and their partners in northwestern Colombia, did not turn up its target bird. However, the team did document 298 species, including several new to Córdoba Department, and the first Harpy Eagle sighting there in 50 years.

For more information, see: abcbirds.org/program/lost-birds

ABC is deeply grateful to Kathleen P. Burger and Glen Gerada, The Constable Foundation, The S. Gale Fund of the Minneapolis Foundation, and Cosmo Le Breton for their generous support of this program.

New Guinea: Black-naped Pheasant-Pigeon

News came out in November 2022 that a team of scientists and conservationists rediscovered the elusive Black-naped Pheasant-Pigeon, a large, ground-dwelling pigeon. Photos and video captured by the team provided the first documentation of the species since 1896. “After a month of searching, seeing those first photos of the pheasant-pigeon felt like finding a unicorn,” says ABC’s Mittermeier, a co-leader of the expedition. “It is the kind of moment you dream about your entire life as a conservationist and birdwatcher.”

Colombia: Santa Marta Sabrewing

This hummingbird was located in July 2022, just the second time it was documented since the species was

7 BIRD CONSERVATION | SPRING 2023

Expedition leader and Madagascar Program Director for The Peregrine Fund Lily-Arison Rene de Roland (left) and Loukman Kalavah of the Peregrine Fund in the forest near a rediscovery site for the Dusky Tetraka.

Photo by John C. Mittermeier.

Dusky Tetraka by John C. Mittermeier

This still shot from a video (Doka Nason) documents rediscovery of New Guinea's Black-naped Pheasant-Pigeon.

Now Available: Collision-curbing BirdTape

ABC BirdTape, an easy, affordable, and effective way to keep birds from hitting your windows, is now available thanks to a partnership of ABC and the company Feather Friendly®.

“We are excited to work with Feather Friendly® to make BirdTape available again,” says Chris Sheppard, ABC’s Glass Collisions Program Director. Created in 2012, the tape has not been available for several years. “It’s a great option for those looking for an inexpensive solution that goes up quickly and lasts a long time.”

“This is a fantastic opportunity to provide even more bird-collision deterrent options and educate

Desert-nesting Seabird, continued

from p.6

Nesting in the inhospitable desert has been a way for these birds to raise their young with few predators, but it has also made conservation a challenge. For decades, while scientists couldn’t locate its colonies, the species was listed as “Data Deficient” on the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Red List, a status that makes it harder to take conservation actions, including advocating for reserves.

ROC worked diligently to locate storm-petrel colonies, scouring miles of desert between 2013 and 2017.

the public about this preventable conservation issue,” says Paul Groleau, Vice President of Feather Friendly®

Birds fly into windows because they do not perceive glass, and instead just see their habitat reflected back at them. This misperception has deadly results, killing hundreds of millions of birds each year. A popular option for individual homes is to put some

kind of visual marker on windows to signal to birds that there is a solid barrier. ABC BirdTape, a white or light blue vinyl material easily applied to windows in long strips or in a pattern of squares, is perfect for this purpose. It lasts four years on average, is translucent enough to allow natural light through and not impact the view outside, and is easy to apply and customize.

ABC BirdTape is available online at featherfriendly.com/.

For other ideas and inspiration about how to reduce bird collisions, visit abcbirds.org/glass-collisions/.

ABC is grateful to the Leon Levy Foundation for its longtime support of our Glass Collisions program.

In 2019, its team released a paper announcing newly discovered Markham’s Storm-Petrel breeding site locations, including the large colony at Pampa Chaca. Resulting population estimates enabled scientists to change the species’ Red List status to “Near Threatened.” With financial support from ABC, ROC worked with the Chilean government to create the reserve.

ROC plans to continue working with ABC to implement monitoring and research programs at the reserve, as well as environmental education initiatives to engage the nearby community.

ABC is thankful for support of this project from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

8 BIRD CONSERVATION | SPRING 2023 ON the WIRE

ROC field team member monitoring Markham's Storm-Petrel nests in the desolate Atacama Desert — an unlikely place for an ocean-going seabird. Photo by ROC.

Photo by ABC

Antioquia Brushfinch: Another “Found” Bird Has a Reserve

More than 15 years after it was first described by scientists and five years after its rediscovery in the wild, the Antioquia Brushfinch has a private reserve to call its own. The 880-acre Antioquia Brushfinch Reserve north of Medellín, Colombia, was acquired by Corporación SalvaMontes Colombia and Corporación Neotropical Innovation, with support from ABC, Conserva Aves, and Rainforest Trust. It is the first reserve dedicated entirely to protecting this Critically Endangered species.

“The area where the brushfinch is located is highly productive, so there’s a lot of cattle ranching and agriculture in the surrounding area,” says ABC International Conservation Project Officer Eliana Fierro-Calderón. “The fact that we now have this stronghold for this species is perfect — it’s the right moment to create a reserve.”

Three searches supported by ABC and organized by local partner SalvaMontes helped pinpoint important areas for protection and enabled an accurate population estimate. To date, the species has been found in 25 locales, most clustered around a small area north of Medellín known as Altiplano Norte de Antioquia. The latest search estimated the species’ total population at 108 individuals. But habitat loss continues. “There are places where the species was found four years ago where they don’t exist anymore, so there has been this urgency of, ‘We need to do something,’” says Fierro-Calderón.

ABC has also supported outreach to local farmers to implement a voluntary conservation strategy that incentivises protecting brushfinch habitat. In 2021, ABC helped put 472 acres of land under conservation agreements with three landowners within the bird’s range.

The new reserve is a little larger than New York City’s Central Park and includes scrub habitat also inhabited by the Black-throated Flowerpiercer (an endemic subspecies), a potentially new antpitta species, and a number of imperiled native plants. Páramo, a kind of native grassland habitat, is also protected within the new reserve.

ABC also supported expansion of a nearby reserve run by partner Fundación Guanacas Bosques de Niebla that also has brushfinch habitat. This January, the Guanacas Reserve added 145 acres of land, bringing its total area to 2,058 acres.

ABC is grateful to The Bobolink Foundation, Stephen and Karen FerrellIngram, Hank Kaestner, the Reissing Family, The Weeden Foundation, and the Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund for their generous support of our efforts to protect the Antioquia Brushfinch.

The Antioquia Brushfinch (left), a yet-to-benamed antpitta, and a view of their new reserve. Photos by Santiago Chiquito.

The Antioquia Brushfinch (left), a yet-to-benamed antpitta, and a view of their new reserve. Photos by Santiago Chiquito.

HABITAT is HOPE

Wood Thrush by William Leaman, Alamy Stock Photo

Wood Thrush by William Leaman, Alamy Stock Photo

However, with your support for habitat conservation efforts, there is hope for birds across the Americas.

Thanks to your generosity, American Bird Conservancy (ABC) is delivering significant conservation results to ensure birds have the habitats they need to thrive across the Western Hemisphere. In 2022 alone, we worked with partners to successfully:

• Plant more than 400,000 trees and shrubs that will benefit some of the world’s most endangered bird species, including Peru’s Royal Cinclodes;

• Improve more than 250,000 acres of habitat for rapidly declining bird species across grasslands, riversides, and forests, including the Chestnutcollared Longspur and Southwestern Willow Flycatcher;

• Create new protected areas totaling more than 43,000 acres for rare species such as Ecuador’s El Oro Parakeet; and

• Make bird habitats safer, both in the air and on the ground — from helping to reduce window collisions and advocating for limits on the use of deadly pesticides, to removing free-roaming cats from bird habitats.

Now, thanks to a dedicated group of supporters, we have a special Habitat is Hope 1:1 Match with a goal of raising $500,000 for bird conservation by June 30. These supporters have already committed $250,000, and ABC is hoping to double that to $500,000 with your help. Your gift today will go far in helping us reach this ambitious goal.

With your help, we can do even more to save wild birds and their habitats, and reverse bird population trends from declining to thriving.

Illustrating how habitat represents hope, there are signs of recovery for the Wood Thrush. Where nesting habitat is optimal — including in areas where ABC and our Appalachian Mountains Joint Venture partners are working — numbers of this silvery-voiced singer are beginning to increase. Please help us expand our work to conserve bird habitat today!

Your gift will be used for crucial conservation projects, allowing ABC to conserve bird habitats and combat daily threats to birds in the most effective ways possible.

We urgently need your support to expand this work for birds across the Americas. Can you help us bring hope to the Eastern Meadowlark, Red-fronted Macaw, Marbled Murrelet, and many other birds?

give us hope, and you give birds a future.

respond with your most generous gift by June 30! Use the enclosed envelope, visit abcbirds.org/HabitatIsHope or scan QR code.

You

Please

Habitat loss is the most urgent threat facing birds today.

BIRDS in BRIEF

World’s First Certified Bird Friendly® Cacao Products Launched

The Smithsonian Zoo and Conservation Institute launched a Bird Friendly® cacao certification in February, following up on a Bird Friendly® coffee certification program launched two decades ago. Now, shoppers can indulge in some of their favorite treats with the assurance that they are sourced from farms with favorable habitat for birds.

ABC helped to facilitate this important milestone, making the connection between partner Zorzal Cacao in the Dominican Republic and the Smithsonian. ABC also supported the implementation of the pilot phase that led to the first-ever certified Bird Friendly® cacao farms.

For more information: bit.ly/BFcocoa

ABC and Partners Continue Fight for Better EPA Regulation of Harmful Insecticides

In February, Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER) and ABC submitted a regulatory filing with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on behalf of 65 nonprofit groups. The filing proposes major reforms in the way the agency regulates systemic insecticides, particularly neonicotinoids (neonics). Neonics are systemic pesticides often applied as agricultural seed coatings that have caused excessive honey bee deaths, native bee declines, and bird mortalities since their introduction more than 20 years ago.

The groups are pushing the EPA to discard a 1984 regulatory waiver

that allows companies to register pesticides without first submitting data on the costs versus the benefits of application. Instead, the Reaganera EPA waiver simply stated: “Rather than require efficacy data the Agency presumes that benefits exceed risks.”

The petition documents how the EPA’s 1984 presumption and its subsequent failure to require efficacy data has led to extensive environmental harm.

ABC is grateful to the Raines Family Fund for its support of our Pesticides Program.

A Bounce for Some Florida Wading Birds

The South Florida Wading Bird Report, published by the South Florida Water Management District in March, summarized results of the bountiful 2021 nesting season, providing good news from perhaps the most important U.S. region for wading birds. All wading birds had a good nesting season above the ten-year average, but a few species did particularly well: the White Ibis (which made up 67 percent of the region’s wading bird nests), Wood Stork, Roseate Spoonbill, and Great Egret. Overall, the report says the impressive 2021 output was “the

second largest annual nesting effort observed since comprehensive systemwide surveys began in South Florida in 1996 and is comparable with reports of large nesting events from the 1940s.” Likely the main reasons for this bonanza: optimal rainfall conditions, dry followed by wet, which provided parent herons, ibis, spoonbills, and storks with a bounty of fish and crayfish.

Wind Project Stalled in Lear’s Macaw Country

In April, a federal judge in Brazil suspended all licenses previously granted to energy company Voltalia to build a wind power facility in the Endangered Lear’s Macaw’s habitat in northeastern Brazil. In his ruling,

12 BIRD CONSERVATION | SPRING 2023

White Ibis by Greg Homel, Natural Elements Productions

the judge said these licenses cannot be granted until legally required Environmental Impact Studies and Environmental Impact Reports are completed and public hearings are held.

The decision was prompted by a lawsuit filed by federal and statelevel public prosecutors in Brazil in March. Local communities have also voiced opposition. For decades, ABC has supported Brazilian partners’ successful efforts to conserve this blue parrot; the ruling adds hope that its recovery will continue.

contributes to the protection of the Chocó region of Ecuador, one of the most highly diverse and threatened tropical forests on the planet,” says Marcelo Tognelli, International Project Officer for ABC.

Lead-Shot Ban in European Wetlands to Save 1 Million Birds Each Year

A lead-shot ban went into effect in February across all 27 European Union countries, plus Iceland, Norway, and Lichtenstein. The ban prohibits use of lead shot in wetlands. According to BirdLife International: “With this law in place, the lives of an estimated 1 million waterbirds which currently die of lead poisoning in the E.U., will be saved and the perpetuation of extreme poisoning of wetland wildlife will be tackled once and for all.”

Ecuador Reserve Expansion Benefits Bounty of Species

Thanks to support from ABC, Ecuador partner Fundación para la Conservación de los Andes Tropicales (FCAT) expanded its reserve protecting some of the world’s last remaining Chocó lowland rainforest habitat. The expansion brings the FCAT Reserve in northwestern Ecuador up to 1,546 acres, improving habitat connectivity and providing added protection for a wide variety of imperiled species including the Endangered Banded Ground-Cuckoo and Vulnerable Long-wattled Umbrellabird.

“ABC is excited to support this reserve expansion because it

Lead shot has been banned in waterfowl hunting across the U.S. since 1991. However, lead shot used in terrestrial habitats and lead fishing tackle are not covered in regional E.U. and U.S. bans, although there are various state- and local-level bans.

Puerto Rican Parrot Numbers Rise

In the 1970s, just 13 wild Puerto Rican Parrots remained on their namesake island. Since then, federal, state, and private partners have worked together on captive breeding and conservation programs for this Critically Endangered, endemic bird.

Efforts were bearing fruit until the back-to-back 2017 hurricanes Maria and Irma devastated the island. The storms killed some of the parrots, severely damaged facilities, and stalled progress, but reintroduction efforts have since revved up. The

parrots are once again nesting at two sites and were reintroduced to a third, Maricao State Forest, in 2022. The estimated wild population is now about 250 birds, with hundreds of captive birds at breeding facilities on the island, which plan more releases.

13 BIRD CONSERVATION | SPRING 2023

Keep up with all the latest American Bird Conservancy news at: abcbirds.org/news/

Puerto Rican Parrot by Tom MacKenzie, USFWS

Banded Ground-Cuckoo by Jordan Franco, Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Waved Albatrosses by givi585, Shutterstock

DEMYSTIFYING ROSY-FINCHES

Understanding the American West’s Off-the-Grid Endemics

by Rebecca Heisman

by Rebecca Heisman

About 250,000 years ago — just a few moments in evolutionary time — small songbirds, likely patterned in brown and pink, island-hopped from Asia to what would become Alaska. Over the ensuing millennia, these birds’ descendants spread across western North America and evolved into three of our continent’s least-studied songbirds: the rosy-finches.

North America’s three rosy-finch species — Black, Browncapped, and Gray-crowned — breed at among the highest altitudes of any birds on the continent, nesting along talus slopes and snowfields at up to 14,000 feet. (A fourth species, the Asian Rosy-Finch, is similarly distributed in northern Asia.) These birds forage for insects and seeds on bare soil and amid sparse tundra vegetation, traveling in small flocks that, because they seldom encounter humans, can be surprisingly tame.

Due to the inaccessibility of rosy-finches’ habitat, many of the surveys traditionally used to assess trends in North American bird populations miss them almost completely. The annual Breeding Bird Survey, for example, is conducted by counting birds along roads. In winter, rosyfinches descend to lower elevations, but their nomadic habits mean that even then, it’s hard to get a handle on their numbers.

The threat of climate change spurs new urgency to learn more about the health of these remote populations. In Utah, Colorado, and beyond, a hardy group of ornithologists is working to unravel the rosy-finches’ secrets, make better estimates of just how many of these birds there are, and predict what will become of them as the cold, snowy mountain reaches they depend on begin to warm.

Ambassadors of the Alpine

When Janice Gardner pictures the animal that best represents alpine habitat for her, she doesn’t imagine a wolverine, a pika, or a ptarmigan. Instead, she thinks of a rosy-finch.

“They’re in the most harsh climates,” she says. “They’re just incredible, hardy birds that don’t seem to be fazed by snowstorms or really nasty winds.”

Gardner, an avid skier, has been familiar with rosyfinches for a long time — they’re known to show up at birdfeeders at some of the West’s most famous ski resorts. An ecologist with a Utah-based conservation nonprofit called the Sageland Collaborative, she’s been heading up, for the past four years, a multipronged effort to answer basic questions about all three rosy-finch species, such as how they move across the landscape.

One component of the project involves fitting birds with leg bands containing individually identifiable microchips that can be “read” by special high-tech feeders hosted by

15 BIRD CONSERVATION | SPRING 2023

LEFT: A Brown-capped Rosy-Finch in alpine habitat in Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado. Photo by Tom Uhlman, Alamy Stock Photo. BELOW: A transect surveyor crossing a talus field in Brown-capped RosyFinch breeding habitat. BOTTOM RIGHT: Brown-capped Rosy-Finch nest and eggs, typically located in a rock crevice. Photos by Shawn Conner.

ski resorts, allowing researchers to follow the movements of individual birds over time and estimate their lifespans. (So far, some tagged birds have continued to reappear for three years.) Another study analyzes isotopes in rosy-finch feathers to determine where the birds were when those feathers were grown. Preliminary results from this project show that Utah is the winter home for Black Rosy-Finches that breed in several Rocky Mountain states, including Montana.

You don’t have to be a scientist to participate in the Rosy-Finch Conservation Project, however. For the past three winters, Gardner has been recruiting volunteers throughout the West to submit counts of rosy-finches at backyard feeders during the winter, when these birds are known to wander widely. Participants from 11 states are now gathering data to help illuminate the details of rosy-finches’ distribution and migration.

Origins of Three Species

While Gardner and her colleagues continue working to analyze their data, another study has provided new hints about how North America’s three rosy-finches came to be in the first place.

During part of the 1980s and early 1990s, all three North American rosy-finches were lumped together as a single species, in part because genetic work had suggested that the differences in their DNA were minimal. In 2020, a team of scientists led by Erik Funk, then a Ph.D. student at the University of Colorado and now a postdoc at the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, published the first study to sequence the entire genomes of this group of birds.

Funk and his colleagues concluded that the Black, Browncapped, and Gray-crowned Rosy-Finches are distinct

enough that they should continue to be considered separate species, but that their populations have continued to interbreed and share genes over time.

The most striking DNA differences between groups of rosy-finches were, unsurprisingly, related to their plumage coloration (each species has its own pattern of brown, gray, black, and pink) and their ability to function at high altitudes. Amazingly, some of the same genetic pathways used by rosy-finch populations to keep their physiological processes going even at low oxygen levels have been found in human populations in the Tibetan Himalayas.

These are genes, with locations in the genome that allow them to be reshuffled and rearranged relatively easily, that provide a clue about how North America’s three species were able to diverge so quickly. Funk speculates that the rosy-finch ancestor crossed the Bering Sea from Asia, “followed by this range expansion south, and then it seems likely that there were probably a couple of different pockets that got isolated by glaciers in the last Ice Age.” Cut off from each other by advancing glaciers, these separated populations continued to evolve on their own species trajectories after the ice receded.

Janice Gardner and Erik Funk are both part of the RosyFinch Working Group, which was formalized in 2021 and includes representatives from state agencies, nonprofits, and universities throughout rosy-finches’ range. The group meets regularly to exchange ideas and set research priorities. One goal is to develop improved, standardized survey methods, finally making it possible to accurately monitor rosy-finch populations. In Colorado, this effort is already beginning to produce results.

BIRD CONSERVATION | SPRING 2023 16

Brown-capped Rosy-Finch art by Chris Vest.

Wintering Resident

One goal of the Rosy-Finch Working Group is to develop improved, standardized survey methods, finally making it possible to accurately monitor rosy-finch populations.

Brown-capped Rosy-Finch range.

“The Hardest Work I’ve Ever Done”

In 2015, the Brown-capped Rosy-Finch, which is found almost exclusively in Colorado, was named a “tier one” species under that state’s Wildlife Action Plan, meaning it is a “species of greatest conservation need.” The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) considers it, and the Black Rosy-Finch, Endangered. As is the case with rosy-finch populations throughout the West, there was a lack of reliable data on the actual health of the Colorado Brown-capped RosyFinch population. But these birds are known for their love of cold and snow, and the state has already been getting warmer — a 2014 report found that Colorado has warmed by more than two degrees Fahrenheit since the mid-1980s, a trend that is predicted to accelerate.

In 2018, Colorado Parks and Wildlife decided to fund a three-year project to finally get some answers about just how many birds were out there. Biologists would trek into the birds’ roadless mountaintop habitats to conduct the first detailed surveys of the species. Kat Bernier, a former wildlife technician for the agency, has been heading up the study as part of her Ph.D. research at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Bernier and her colleagues randomly selected 57 mountain basins within potential rosy-finch habitat. At each one, a pair of surveyors walked parallel line transects while counting and recording the birds they saw.

The first word Bernier uses to describe the surveys is “grueling.” “Often we would start pre-dawn and hike several miles up a trail to access a site, and then hike offtrail to get into the actual position where we would do our surveys,” she says. “Then it was a long day of walking slowly and looking for birds on 45-degree rock slopes, on unstable footing and crumbling rock. The rosy-finch project is by far the hardest wildlife technician work I’ve ever done, just because of the steep, rugged terrain.”

After three years of hard work, Bernier and her colleagues finalized their results in early 2023: Colorado, according to their analysis, is home to an estimated population of between 115,000 and 150,000 Brown-capped Rosy-Finches — more than three times the estimated total population listed in a Partners in Flight report from 2016. Contrary to what some had feared, this is a healthy population.

Bernier and her fellow biologists also documented the habitat features where they found the birds. Rosy-finches preferred to spend time near cliffs and snow patches, avoiding areas with dense vegetation, and were most common at elevations between 11,500 and 13,200 feet.

Bernier says that she, at least, was not surprised by the robust numbers of birds they found. “I had so many years of experience in the alpine of Colorado, surveying [other wildlife],” she says, “and rosy-finches were everywhere, all of the time.” A similar assessment in Idaho focusing on Black Rosy-Finches is currently underway, although the results are not yet public.

These results provide an important baseline for future monitoring. Colorado Parks and Wildlife plans to repeat these surveys periodically using the same methods to get a better sense of whether the population is holding steady, or if it will begin to decline as climate change further alters the Brown-capped Rosy-Finch’s habitat.

If counting how many rosy-finches there are now is hard, predicting the future may be even harder. But at least some scientists who study rosy-finches believe that these little pink-and-brown birds may prove surprisingly resilient.

A Rosy Future?

According to a 2019 report by the National Audubon Society, if Earth’s climate warms by just two degrees Celsius (about 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit), the Gray-crowned Rosy-Finch will lose 48 percent of its current suitable

17 BIRD CONSERVATION | SPRING 2023

Wintering Resident

Black Rosy-Finch art by Chris Vest.

Black Rosy-Finch range.

habitat, the Black Rosy-Finch will lose 79 percent, and the Brown-capped Rosy-Finch, the species on which Kat Bernier focused, will lose a staggering 99 percent. There is reason to be gravely concerned about these birds’ future. But don’t count them out just yet.

Matt DeSaix, a Ph.D. student with Colorado State University’s Bird Genoscape Project, headed up a new genetic analysis of Brown-capped Rosy-Finches that was published last year, with an eye to both the species’ current genetic health and what the future might hold. He and his colleagues sequenced genes from feather and blood samples collected from birds at 11 sites spanning the species’ breeding range. They found no concerning lack of genetic diversity, nor any evidence of inbreeding at any of their sites, supporting Bernier’s conclusion that the population is robust.

They also attempted to peer into a genetic crystal ball. DeSaix’s project combined two methods of forecasting what might happen to rosy-finches in a warming world: ecological niche modeling, which looks at how the distribution of habitat meeting a species’ current requirements is likely to shift in the future, and genomic offset, which looks at how much genetic adaptation a population would likely have to undergo to keep up with changing climate conditions in the birds’ current home.

DeSaix’s analysis suggests that the area of good rosyfinch habitat will contract and that some amount of natural selection will need to happen for populations’ local adaptations to continue to fit the places they live. “It’s both,” he says. “They’re going to have less suitable habitat, and to stay within this area, they’re going to need to adapt as well.”

But, he cautions, we still really don’t know enough about these birds and how they use their habitats to say for sure what will happen. For one thing, the highly varied jumble of ridges and basins in their mountain habitat can create small pockets of cooler habitat that persist at lower elevations even as the area around them warms.

Pika, small relatives of rabbits that rely on similar alpine habitat, have already shown an ability to make use of these “microhabitats” to adapt to changing conditions.

DeSaix is optimistic about rosy-finches’ prospects. “So many people are just stoked about rosy-finches and want to protect them, and I’m happy seeing the high genetic connectivity, I’m happy seeing the stable base populations,” he says. Climate forecasting, he points out, is inherently uncertain.

According to Janice Gardner, the Rosy-Finch Working Group is already striving to identify potential ways to help buffer rosy-finches against the worst effects of climate change. Possibilities they hope to explore include improving habitat in the birds’ lower-elevation winter ranges by promoting native plants and fighting invasive weeds, and physically removing trees that may encroach upslope into rosy-finches’ winter foraging habitat as temperatures warm.

“I’m hopeful that the story of the rosy-finches is a good one and that we can ensure that they persist into the future,” she says. “They’re really neat species that I think a lot of people [in the West] can relate to — they like a good snowstorm like a skier does, and they’re kind of desert rats, too — they can be a bit nomadic.”

When asked if she identifies with rosy-finches a little bit, she laughs. “Maybe I wish I was more like a rosy-finch,” she admits, “instead of being stuck here reading emails all day.”

Those living in rosy-finch territory can learn how to submit feeder counts to the Rosy-Finch Conservation Project — including reports of no rosy-finches, which are also valuable. Visit: sagelandcollaborative.org/rosy-finch.

Rebecca Heisman is a science writer based in eastern Washington. You can find her online at rebeccaheisman.com

BIRD CONSERVATION | SPRING 2023 18

Gray-crowned Rosy-Finch art by Chris Vest.

Gray-crowned Rosy-Finch range.

HELPING BIRDS WEATHER CLIMATE CHANGE

by David A. Wiedenfeld

Rosy-finches are not the only species facing uncertain futures. Climate change menaces birds in many ways, but conservationists are already hard at work tackling some of the most significant threats. Below are some strategies for adaptation and mitigation being used by ABC, our partners, and other conservationists — each for a different threat posed by climate change.

Fire Prevention and Control

Although fire is a key naturally occurring component of fire-adapted ecosystems, including many grasslands and some kinds of woodlands, climate-change-driven wildfire is an increasing threat to areas protected for the conservation of birds. This is especially true for habitat types that are not fire-adapted, like many humid forests and cloud forests, where no fire may have occurred for centuries. As climate change raises temperatures, drying vegetation and drought can become more common, increasing the risk posed by wildfire.

For example, in central Brazil’s cerrado habitat, fires driven by climate change have threatened protected areas. With ABC support, local partner organization Instituto Araguaia developed a fire control program to extinguish blazes before they destroy protected habitat. The Kaempfer’s Woodpecker (above) and Bare-faced Curassow, both listed as Vulnerable to extinction by the IUCN, still have a place to live and thrive, but the threat of devastating fire is an eye-opener, not only in this region but throughout Latin America and in North America as well. There, wildfires could possibly threaten habitat for species such as the Gunnison Sage-Grouse, as well as areas of the Arctic protected for nesting waterfowl and shorebirds.

Planting Trees for Birds and Carbon Storage

Reforestation is a key action, providing habitat and protecting watersheds. ABC has supported the planting of 7.4 million trees and shrubs in reserves and buffer areas, including high in the Peruvian Andes, where ABC’s partner Asociación Ecosistemas Andinos (ECOAN) has mobilized local communities to plant over 1.6 million trees, restoring queuña woodlands (composed mainly of trees in the genus Polylepis) that not only help protect watersheds and capture water, but also provide key habitat for the Royal Cinclodes, Whitebrowed Tit-Spinetail (above), and other birds found almost nowhere else. Of course, reforestation itself can help sequester carbon, and even without regard to improving bird habitat, tree-planting helps reduce greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Countering Sea Level Rise’s Coastal Impacts

Sea level rise is crowding out coastal marsh birds like the Saltmarsh Sparrow (above) and Black Rail. Human structures, like causeways, seawalls, and dikes, are more and more preventing the tidal flooding of marshes and narrowing the space where marshes can form. As part of the Atlantic Coast Joint Venture, ABC works with partners like the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, U.S. Forest Service, and Ducks Unlimited to support efforts to keep marshes as marshes, and restore or even build new marshes as sea level rises, especially along the coasts of North and South Carolina. Among many other benefits, these wetlands could potentially provide federally Threatened Eastern Black Rails with sufficient habitat to maintain East Coast populations.

On Islands, Seeking Higher Ground

Low-lying atolls in the Hawaiian chain and elsewhere that host large seabird colonies are already being inundated by storm surges, destroying nests or young. Scientists predict this will continue to get worse. One way to mitigate this danger: encourage colonial seabirds to nest on islands with higher ground, above the level of the surge. ABC is working with partner Molokai Land Trust to protect former seabird habitat from invasive predators, and then to attract seabirds there, such as the Laysan Albatross (above) One way to draw in these birds and habituate them to a site is by playing recordings of the seabirds’ calls, and placing out model birds (decoys), making the place seem already occupied to birds passing by.

Extending Conservation Upward and Poleward

Another clearly important goal is to protect habitat at higher elevations or further to the north of places where bird species now occur. That way, the birds will have protected areas when their habitat shifts. In coming decades, birds including Ecuador’s Endangered El Oro Parakeet (above) will likely benefit from such efforts: Fundación Jocotoco and ABC recently worked together to expand habitat protection to higher elevations to benefit this and other species at the Buenaventura

19 BIRD CONSERVATION | SPRING 2023

Reserve.

David A. Wiedenfeld is ABC’s Senior Conservation Scientist.

Photo credits, clockwise from top left: Kaempfer's Woodpecker by Ciro Albano. Saltmarsh Sparrow by Betty Rizzotti. Laysan Albatross by Bill Hubick. El Oro Parakeet by Dušan Brinkhuizen. White-browed Tit-Spinetail by David Fisher, Neotropical Bird Club.

ABC BIRDING

Palila Forest Discovery Trail, Hawai'i

By Chris Farmer, ABC’s Hawai‘i Program Director

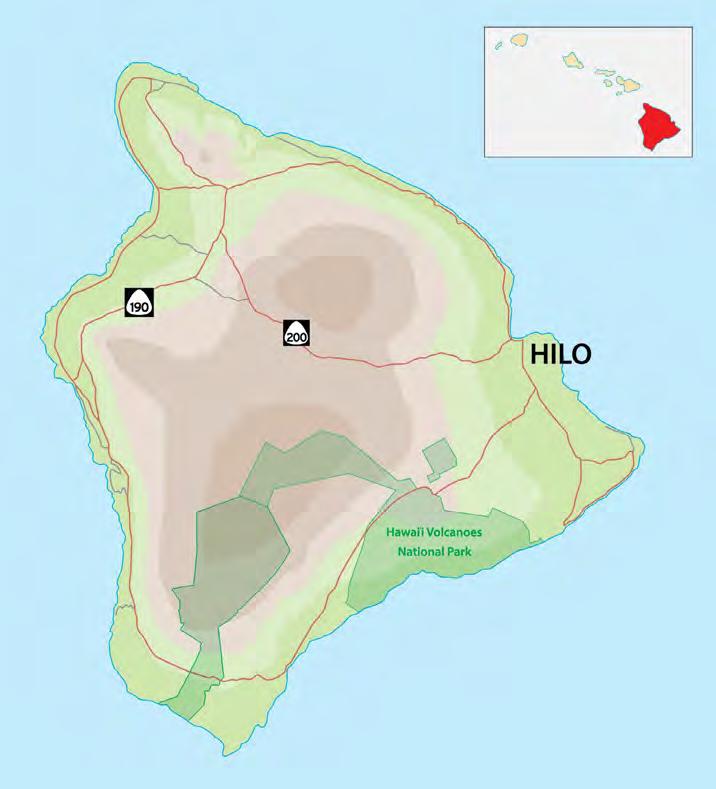

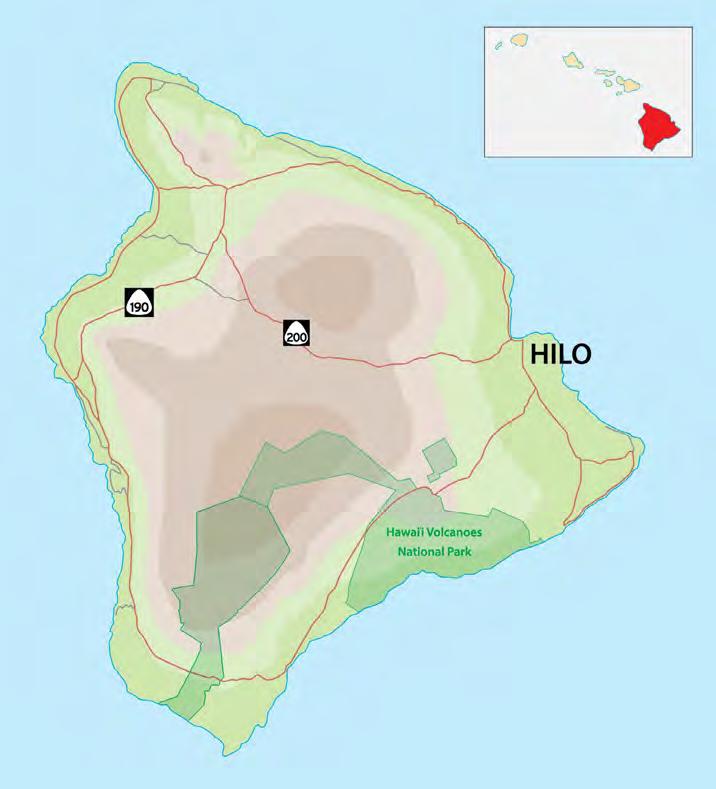

Lay of the Land: Located on the island of Hawai‘i, the Mauna Kea Forest Reserve’s Palila Forest Discovery Trail — designed and supported with help from ABC — goes through one of the largest remaining tracts of high-elevation dry forest remaining in the state. Accessible only via four-wheel-drive vehicle, this area is home to the Critically Endangered Palila, a yellow-headed songbird with a thick black bill adapted to crack open tough pods of the Māmane tree. At around 7,300 feet, this dry area occurs above the wetter ‘Ōhi‘a and Koa forests found below.

Focal Birds: Unfortunately, the trail’s namesake Palila is in steep decline. The latest count in

February 2022 yielded an estimate of 678 birds remaining in the wild. Because of their scarcity, these gorgeous, melodic honeycreepers can be hard to find without dedication and perseverance. However, other native birds are likely to be seen on a visit to the trail: Hawai‘i ‘Elepaio (listen for their squeaky dog-toy calls), Hawai‘i ‘Amakihi, and if you’re fortunate, Pueo, the endemic subspecies of the Short-eared Owl. Hawai‘i also hosts many introduced bird species. Those frequently seen and heard here include: Erckel’s Spurfowl, California Quail, Eurasian Skylark, Japanese Bush Warbler, Warbling White-eye, and Red-billed Leiothrix.

Other Wildlife: Hawai‘i has no native amphibians or reptiles, and just one land mammal, a bat. However, many non-native mammals are

LEFT: Palila by David Brock, Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. ABOVE: The Palila Forest Discovery Trail is one of the best places to seek this thick-billed, dry-forest Hawaiian honeycreeper. Photo by Mike Parr.

now present in the area. (See “Conservation Activities” below.)

Along the trail, visitors find a series of signs pointing out natural history features and vegetation. Māmane is one of the dominant trees, with small compound leaves, bright yellow flowers, and distinctive, leathery seed pods. The other common tree in this area is Naio — which is favored by Hawai‘i ‘Elepaio. Another notable feature is the small, protected grove of an endemic sandalwood or ‘iliahi (Santalum paniculatum), renowned for its fragrant flowers and wood.

When to Visit: The trail is open yearround during the day, but requires a four-wheel-drive vehicle. Any access can prove difficult during the rainy season, from November to March. Be aware that this area is high (you might feel the altitude), dry (no smoking or parking in grass), and the surrounding areas periodically have hunters present.

Conservation Activities: Now confined to this high-altitude forest, Palila face multiple threats: Introduced sheep and goats destroy and degrade the habitat, non-native cats and mongooses kill Palila chicks and nesting adults, rats take eggs,

and invasive plants hinder growth of beneficial native plants and increase fire risk. Climate change has altered the rainfall pattern, and with rising temperatures, introduced mosquitoes are moving to higher elevations on Mauna Kea. Like many of the islands’ other native forest birds, Palila are highly susceptible to avian malaria transmitted by these insects. Fortunately, for now, Palila live at an elevation where mosquitoes are unable to successfully reproduce.

To improve the forest and protect Palila, ABC is working with partners in Hawai‘i like the Mauna Kea Forest Restoration Project to plant thousands of native trees each year and remove non-native predators. As part of the Birds, Not Mosquitoes initiative, we are working across the state in an urgent effort to break the avian disease cycle and protect Palila and the other honeycreepers.

Directions: From Hilo, head west on State Route 200 (Saddle Road), passing Mauna Kea Observatory and Pōhakuloa Training Area, then bear right on the road to Waiki‘i. After going up a series of small hills, there will be a sharp right turn onto an uphill dirt road and a hunter checkin station. Stay on this road, R-1, as it climbs. The large parking lot for

the Palila Forest Discovery Trail will be on the left side, approximately 3.8 miles from the paved road.

From Kailua-Kona: Head north on State Route 190, then turn right onto State Route 200 heading to Waiki‘i, then turn left onto the dirt road (and follow directions above).

In the Area: On the drive west from Hilo along Saddle Road (Route 200), there are two easy-access stops where native forest songbirds can be seen and heard. At Kaulana Manu Nature Trail (22 miles west of Hilo), there is a short loop trail and the parking lot has a great vantage point looking into the canopy. This is one of the best places on the island to see the following native forest birds: ‘I‘iwi, ‘Ōma‘o, ‘Apapane, and Hawai‘i ‘Amakihi (although the Palila Forest Discovery Trail is a better place to find the latter species). West another 1.4 miles on Saddle Road lies Pu‘u ‘Ō‘ō Trail, a longer hike where, in addition to the more common native songbirds mentioned for the last trail, there is the possibility of ‘Io (Hawaiian Hawk) and also a remote chance of finding two Endangered species, ‘Akiapōlā‘au and ‘Alawī or Hawai‘i Creeper.

For more information, see: bit.ly/HIbirding

BIRD CONSERVATION | SPRING 2023 22

Hawai'i 'Elepaio (Mauna Kea) by John C. Mittermeier.

Hawai'i 'Amakihi by Robby Kohley.

Pueo (Hawaiian Short-eared Owl).

Photo by Jack Jeffrey.

HAWAI'I ISLAND

Waimea

KAILUAKONA

Saddle Road

Ka'ohe Restoration Area Palila Forest Discovery Trail

Kaulana Manu Nature Trail

Palila (below) by Aaron Maizlish, Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. View of the Palila Forest Discovery Trail (bottom) by Mike Parr.

Pu'u 'O'o Trail

Waimea

KAILUAKONA

Saddle Road

Ka'ohe Restoration Area Palila Forest Discovery Trail

Kaulana Manu Nature Trail

Palila (below) by Aaron Maizlish, Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. View of the Palila Forest Discovery Trail (bottom) by Mike Parr.

Pu'u 'O'o Trail

Birds Mean Business in Ecuador’s Andes

Straddling the Andes and equator in northern Ecuador, Pichincha Province resembles a jagged swift gliding east across the map. In an area smaller than Connecticut, the province hosts over 850 bird species — more than recorded across either of the world’s two largest countries, Russia or Canada. The capital Quito sits at its heart, but another of Pichincha Province’s crown jewels, the Mindo Region, lies nestled in subtropical cloud forest to the west, in an area now considered one of the world’s top birding destinations.

by Howard Youth

There are many bird-rich places around the world, including others in the Andes. How did the rustic little town of Mindo come to rule the roost? It took the blending of a few key ingredients: a big dash of spectacular species, a dose of easy accessibility, and the X factor — a major, home-grown passion for birds. Mindo’s recipe provides a top-flight model for other regions around the world, to cash in on bird tourism while deepening environmental awareness and bolstering conservation efforts.

The Road to Success

“I would say that 50 percent of Mindo’s population is directly dedicated to [the business of] birdwatching,”

25 BIRD CONSERVATION | SPRING 2023

How winged creatures provide wonder, inspiration, and prosperity in one of the world’s birdiest regions.

FACING PAGE: A Plate-billed Mountain-Toucan checks out a water feature at Birdwatcher's House. Photo by Vinicio Pérez. TOP: ABC Vice President of Threatened Species Daniel J. Lebbin poses beneath a tall cock-of-the-rock sculpture marking the highway turnoff to the town of Mindo. Photo by Mike Parr.

says Vinicio Pérez, who has lived in the town 45 years, guiding professionally for 34 of those. Pérez estimates that the other half of the workforce is involved in other nature and adventure tourism (general guiding and ziplining, for example), farming, or small businesses in and around town.

It wasn’t always that way, although a bond between Mindo’s birds and people always existed. The area’s birds, from high-elevation forests around the town of Nono down to foothill level in San Miguel de Los Bancos, became known to ornithologists starting in the 1800s and early 1900s, when Ecuadorian bird collectors were active there. Later, a road snaked west from Quito, navigating this region’s forest-cloaked mountains on its way down toward the Pacific. This ribbon of road was a welcome mat for generations of small farmers, many of whom moved in and cleared patches of cloud forest for their homesteads.

Residents new and old knew their bird neighbors. Guans, pigeons, and some other large birds graced some dinner tables, while hummingbirds, the red-orange Andean Cock-of-the-rock, and a rainbow of tanager species dazzled residents and periodic visitors descending the highway from Quito.

Then, in the late 1980s, tourism to Ecuador’s famed Galápagos Islands skyrocketed, and Mindo popped up as a mainland add-on to some international travel itineraries. After all, this cornucopia of birding bliss sat just a two-hour drive from the country’s capital and airline hub. Visitors came looking for guides and some local farmers were happy to oblige.

Pérez recalls his first guiding experience at this time, when he was hired to take a few tourists around for a week in 1989. “Of course, then, I did not speak English,” he says, “and I did not know the names of birds in English, but I did know the songs and knew what bird and family I was seeing.”

The job was a dream come true for Pérez. “I was born in San Miguel de Los Bancos, a town very close to Mindo. I lived there until 1978, the year that my parents and I moved to Mindo to live on a farm that my father bought. By that time, I was already very interested in birds,” he says. The year after he first guided, Pérez opened the second hotel in the town of Mindo, called Birdwatcher’s House. “I started with three rooms and a shared bathroom,” he notes.

Julia Patiño, another veteran Mindo guide, had a similar start. She was born to the south, in El Oro Province, but moved to Mindo with her parents when she was five. She still lives there, and she and her cousins Natalia and Sandra are professional guides. “One of the main reasons why I started guiding in 1998 was because I liked nature, seeing the birds, looking at their colors, and listening to their songs,” Patiño explains. “All of this was very fun, and with that, being a guide became my job, a source of income for my family.”

Something to Count On

Mindo’s guides came to lead a movement that has since spread. “It all started with the Christmas Bird Count,” says Patiño, who has worked on this voluntary effort for many years. “From there, we have helped to carry out bird counts in other parts of Ecuador, being leaders of routes and sharing our experiences,” she says. “Now, Ecuador has 30 bird counts.”

Annual Christmas Bird Counts (CBCs) started in the United States and Canada in 1900, when the Audubon Society established the winter bird tallies to counter traditional holiday bird hunts. Over the years, the number of counts grew, and they spread into South America. Ecuador’s very first CBC took place in 1994 in the Mindo area, four years after Pérez’s hotel opened. Then, a dozen birders racked up 250 species in and around town. Since then, the area’s count has often been a chart-topper. For example, 134 participants in the “Nature Guides of Mindo” team tallied 389 bird species on December 18, 2021 — the highest of all 2,621 CBCs that year.

Two years after the first Mindo count, Guy M. Kirwan and Tim Marlow published an article in the journal Cotinga that provided the first full species inventory for the town of Mindo and areas within a half-day’s hike — an important baseline list followed by guides and visitors. Of the 334 documented species, 41 percent were endemic to the Chocó ecoregion, which runs only from western Colombia to western Ecuador. (According to BirdLife International, at more than 50 species, the Chocó Endemic Bird Area, or EBA, “supports the largest number of restricted-range birds of any EBA in the Americas….”)

A map included in the article shows a far smaller town than exists today, with only a few trails known to birders, and with just one or two places to stay. But local guides were already busy leading birders through the misty

BIRD CONSERVATION | SPRING 2023 26

Mindo Region, ECUADOR

27 BIRD CONSERVATION | SPRING 2023 QUITO ECUADOR EQUATOR

Nono Yanacocha Reserve Pichincha Volcano “Eco-route” Nono-Mindo Road Bellavista Cloud Forest Reserve and Lodge Birdwatcher’s House

Sanctuary

Mindo

Milpe Bird

San Miguel de Los Bancos

Clockwise from top left: Displaying male Club-winged Manakin. Photo by David Fisher, Neotropical Bird Club. Hummingbirds probe a hand-held feeder at Birdwatcher's House. Photo by Mike Parr. Veteran Mindo guide Julia Patiño.

Photo by Brenda Durán. A bird-themed guest room in Birdwatcher's House. Photo by Vinicio Pérez.

cloud forest to find staples such as the Andean Cockof-the-rock, Golden-headed Quetzal, Red-billed and Bronze-winged Parrots, and hummingbirds including the Velvet-purple Coronet, a gem of a bird near the southern edge of its small range (see cover).

A few years after Patiño began guiding visitors, the definitive field guide to Ecuador’s birds was published. More than 20 years in the making, The Birds of Ecuador by Robert S. Ridgely and Paul J. Greenfield, later translated into Spanish, was published with the “hope that the gradually increasing number of Ecuadorian nationals conducting research or simply going out to observe and enjoy birds will continue to increase.”

Many hotels incorporated birds and feeders as visible garden "fixtures," and local farmer Angel Paz pioneered a technique for “training” shy antpittas to hop from the forest cover to feed on offered worms. For more on Paz, see: abcbirds.org/AngelPaz

The Changing Nature of Things

Since stepping onto the birding world stage, the town of Mindo has almost tripled in population and crept past former boundaries. Pérez says the growth has at times been chaotic and poorly planned. He moved outside the town to a 42-acre property that now offers 11 rooms, each with a private bathroom, adjacent to the sprawling 48,000-acre Mindo-Nambillo Protected Forest. The growth certainly has its trade-offs, in increased traffic and building. But dozens of private reserves with lodging, like Pérez’s, now sprinkle the region.

“Mindo and its surroundings continue with conservation and the care of the environment,” says Julia Patiño, “and I believe that the community of Mindo guides is kept strong by the passion for birds, conservation, and the care of the environment.” This enthusiasm and conservation ethic now echo far beyond the region. In Ecuador, visiting nature reserves is now a popular pursuit of domestic and international travelers alike.

“The perception towards nature and its conservation has changed drastically over the past 20-plus years,” says Martin Schaefer, CEO of Fundación Jocotoco, with whom ABC partners. Jocotoco has 16 reserves across Ecuador. One of the most popular is Yanacocha, which covers nearly 3,000 acres of high-elevation cloud forest and grass-and-shrub páramo almost overlooking Quito.

“People in Ecuador have become aware of environmental problems that they were unaware of previously, from

BIRD CONSERVATION | SPRING 2023 28

FROM TOP: Fundación Jocotoco’s Martin Schaefer notes a sea-change in environmental concern in Ecuador. The eye-popping Sword-billed Hummingbird.

Photos by Mike Parr. Entrance to Yanacocha Reserve. Photo by Gemma Radko.

Partnership in Pichincha and Beyond

Ecuador ranks fifth in the world for total bird diversity, after the far-larger countries of Colombia, Peru, Brazil, and Indonesia. In all, this Colorado-sized nation boasts 1,670 species, many of them with small ranges. For 25 years, ABC and Fundación Jocotoco have worked together to save the country’s bird bounty, especially its rarest species, from Great Green Macaws to Pale-headed Brushfinches. ABC has supported expansion, management, and habitat conservation and restoration efforts at Jocotoco reserves since that organization was founded in 1998. The partnership continues. Ongoing efforts to expand and improve conservation at Jocotoco’s Río Canandé Reserve, where more than 400 bird species have been recorded, provides just one example of how the two organizations’ time-tested collaboration benefits one of the most biologically diverse parts of the planet.

— Howard Youth

climate change to pollution,” says Schaefer. “Many Quiteños come to visit Yanacocha these days, even in the absence of them being avid birders or hardcore naturalists, the typical crowd of 20 years ago,” he adds.

At Yanacocha, virtually all of the 6,000-plus annual visitors come face-to-face with at least a half-dozen hummingbird species as they stroll past feeders maintained along what was originally an Incan road. Many cross paths with the Sword-billed Hummingbird, a freak of nature with a bill as long as its body — and a few have the great fortune to spy the Critically Endangered Black-breasted Puffleg, a tiny hummingbird that finds a last refuge at Yanacocha and its vicinity.

This reserve sits near one end of the original winding road from Quito to the Mindo area. Once flanked by a widening margin of cleared pastures and small farms, the Nono-Mindo Road, since the construction of a new highway a few decades ago, is far less travelled these days. It was along this road over 30 years ago that Richard and Gloria Parsons established the country’s first registered Private Protected Area. The Bellavista Cloud Forest Reserve and Lodge spans 988 acres and, over the years, has been joined by other private reserves popping up along this road, which is now considered an “eco-route.”

Referring back to the example of the Mindo area, Schaefer reflects on how the snowball effect of nature tourism’s popularity began humbly: “The changes in the Mindo/ Los Bancos area really go back 30 years,” he says. “Back then, a number of committed people joined forces and converted Mindo into a hub for nature lovers. Crucially, this has always been a grassroots movement, rather than one being monopolized by a single institution.”

Positive Impacts

Birds are a major “crop” cultivated at the area’s private reserves. Conserving — and restoring — habitat is key. Habitat brings birds, and birds delight visitors, many

of whom return home with a growing appreciation of conservation efforts.

Not far west of Mindo, where the Pacific Slope descends to steamy foothill forest, the Mindo Cloudforest Foundation’s (MCF’s) Milpe Bird Sanctuary hosts a bounty of birds — including in areas that were, not too long ago, virtually bird-free pasture. I first visited Milpe in 2005, the year after its founding, and remember watching hummingbirds dart from the forest to feeders in a sun-stroked clearing. At the time, staff were removing dense patches of invasive pasture grass so they could plant young native trees there. Five years later, I returned but could not find the feeder spot … until I realized the site was enveloped in full shade, beneath a canopy of young forest. Overhead, redcapped, round-bodied Club-winged Manakins competed for mates, vibrating their wings more than 100 times per second to produce a resonating sound: “Bik Bik BAAHT!” Like many birds there, this species is endemic to the Chocó ecoregion. MCF has other properties nearby, including the Santuario de Aves Río Silanche, where ABC funded the purchase of 210 acres to launch the reserve in 2006.

Visiting Yanacocha or Mindo or Milpe, you get the feeling you could spend a lifetime in this small area and unlock only a fraction of Pichincha Province’s natural secrets. As the planet’s amazing biodiversity faces ever-greater challenges, perhaps there’s no better place to see how business and birds can help balance out the needs of humanity, while bringing us back to nature.

29 BIRD CONSERVATION | SPRING 2023

Howard Youth is ABC’s Senior Writer/Editor.

Dawn Songs

For Birds and Humanity, a United, Diverse Voice

Dawn Songs: A Birdwatcher’s Field Guide to the Poetics of Migration is an anthology edited by Jamie K. Reaser and J. Drew Lanham. The book features lyrical reflections on humanity’s relationships with birds through the works of 60 writers. Proceeds from the book will support ABC’s Conservation and Justice Fellowship program, which seeks to expand the intersections between biodiversity conservation and environmental justice. Learn more: bit.ly/ABCfellowships

About the editors: Jamie K. Reaser is an ecologist, international policy negotiator, and award-winning literary writer. She is cofounder of the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center and International [World] Migratory Bird Day.

On the following pages, we ask the editors a few questions, and share excerpts from the book.

What was the inspiration for creating this book?

May 13th, 2023, is the 30th Anniversary of International Migratory Bird Day (now World Migratory Bird Day). I (Jamie) co-founded IMBD when I served as Bird Conservation Specialist for the Smithsonian Bird Conservation Center and Co-Chair of the Partners in Flight Education and Outreach Working Group. The intent for IMBD was, first and foremost, to celebrate Neotropical migratory birds and the migration phenomenon. Through Dawn Songs, I wanted to respark that spirit of celebration for the birds and in the human heart. To protect life — birds and other species — we need to bring ourselves back to life by falling in love with the world again, to remember our place as a part of rather than apart from Nature. Celebration is generative. What if humans got up every morning at dawn, stepped outside, and sang? Perhaps migratory birds can show us the way home.

How did you go about selecting what to include?

We reached out to the authors — people we know who, like ourselves, write at the interface of Nature and human nature. Many are well-established writers in poetry and lyrical prose genres. Others are people who have had fewer opportunities to voice their stories and sentiments. One of our intents in bringing Dawn Songs together was to amplify such voices, to invite the lesser-known authors onto a perch from which they could be better heard. And, of course, authors we invited reached out and invited other authors along the way. This was also part of the book’s intent: that we held our vision for it loosely, let it become what it wanted to become. It became a chorus 60 voices strong.

What do you hope Dawn Songs will accomplish?

Dawn Songs is more than a book: It is an invocation, a calling together of birds and birdwatchers across diverse landscapes and indefinite identities. It is a celebration of what unites us at the edges of Nature and human nature. It is, in part, Emily Dickinson's "Hope [being] the thing with feathers." The Reader's Guide at the end of the book is intended to guide the reader into the deep terrain of birds and birdwatching through contemplative practices — thought-provoking and heart-opening explorations of the poems, essays, and song lyrics.

What inspired the decision to give the book’s proceeds to ABC’s Conservation and Justice Fellowship Program?

Shared fate is the plight of birds and human beings. Ultimately, we need to find ways to survive (and hopefully thrive) in the same air, the same water, the same soil — all on this same Earth, broadening the scope of bird love, care, and concern to others beyond the traditional conservation "choir." Our dawn chorus gives voice in a different way and hopefully a means through donation of the proceeds, to support and inspire others to sing for better for birds and us, too.

Dawn Songs is available from online retailers and bookstores.

Learn more and engage with others enjoying Dawn Songs: Visit Facebook and YouTube and search for "Dawn Songs book."

LEFT: Photo by Shaun Wilkinson, Shutterstock

J. Drew Lanham is an Alumni Distinguished Professor of Conservation and Cultural Ornithology at Clemson University. He received the MacArthur Foundation Fellowship in 2022.

The Yellow Warbler

Jamie K. Reaser

Jamie K. Reaser

Bold and bright, with a soul-stirring desire to couple and nest and tend he sings from the willow branch, and the day is suddenly delightful to every living thing — the awakened and arrived. Spring!

The cold wintered-heart cracks, melts, reveals a reason to keep on living, and doing so with blessings counted out in the open, unabashedly. You’ve noticed, right? in your very own chest, and you’ve listened, yes? and you’ve called out, haven’t you? for the company that could turn a solitary moment into a renewal of faith in the worth of tomorrow, and perhaps even the years that follow that. How could you not?

Oh, whistle sweetly into the blue morning yellow warbler, whistle sweetly dear little bird, dare, remind us, life is beauteous — so worth showing up for with great self-expression from a high leafy pulpit, though we may be so deeply tired, aren’t we? from our long, arduous journey.

Let there be no excuses.

Yellow Warbler by Matthew Jolley, Shutterstock

Thrush Love

J. Drew Lanham

J. Drew Lanham

In an attempt to make my worn suburban surroundings more thrush-philic I’ve let things go past “maintenance.” Let things grow beyond containers or neat bed borders.

Opened the door to what some would call “weeds.”

Welcomed all feathered things olive-backed and skulky.

Rolled out a welcome mat of disarray. Made glimpses of pieces and parts of what might be, the priority.

I’ve let the dank rank higher than bright. Encouraged shadows to persist at all hours.

Let snails have right of way. Asked the olive-backed birds if warblers and other night travelers might find such an ill-kempt place to their liking. Ferns, four-o’clocks, sumac, poke salad and yes even un-American things like privet find function here, so long as the trans-gulf travelers approve. Gray cheeked-esque, Swainsonii-like or wood-ishness not withstanding, Could a Bicknell find my spot inviting? But then I would only know if it chose to speak. My goal in enhancing thrushiness has not been to increase any lists, but more simple want, desire wish.

To be a spot on the map below starlit transit, that by dawn is worthy of a pause to snatch a nap’s wink or late worm.

A link in some chain of a chance to make it further South to perhaps return again.

Wood Thrush by Larry Master, masterimages.org

Jorge Hernando Osorio lives along the basin of the Río Chinchiná in a small Colombian village between Medellín and Bogotá. With his wife Gladys Patiño, he founded a bird observation group called “Espigueros, Guardianes de los Torrentes” (“Seedeaters, Guardians of the Torrents”). Their activities are supported through the Paisajes Sostenibles (Sustainable Landscapes) project (PASOS), a multi-partner initiative that includes ABC, VivoCuenca, the Caldas Department Coffee Producer Committee, Ecological Coffee Foundation, and the Caldas Hydroelectric Company (CHEC). This is Jorge’s story, in his own words:

I now work in this area dedicated to observing birds, at a moment when there is a real passion for birdwatching. I have worked in artisanal river-sand mining for many years, and throughout this time, I have always been observing birds and learning about them.

My passion for birds started around five years ago, after I had the opportunity to meet some people down by the river. They were watching Torrent Ducks. After they told me they were down here just to observe birds, I wanted to learn how to identify different species, too.

Along the way, I have learned that by knowing how to watch and identify birds, the community can understand how to value, care for, and protect the species, many of them imperiled, in our areas.

I also work with the young ones, helping them make a connection with nature. It’s important that the community know about the protection of the environment. When we don’t know, at times we harm through ignorance the very important species we have in our areas.

I also work with community nurseries of the PASOS project. The majority of plants we grow and plant are native trees that benefit wildlife, including parrots, tanagers, hummingbirds, and migratory species. The “sustainable landscape” is how you recuperate what had been lost. We can all be an important part of this.

Award-winning watercolor painter Beatriz Benavente lives in Spain, where she specializes in scientific and bird illustration. You can follow her on Instagram: www.instagram.com/wildstories.art

WILL YOU BE THEIR HOPE?

Be their hope. Leave your legacy for birds.

If you are interested in more information on how to leave your own legacy for birds, or if you have already remembered ABC in your will, or as a beneficiary of a trust, IRA, or insurance plan, please contact Jack Morrison, ABC Director of Major Gifts and Planned Giving, at jmorrison@abcbirds.org or 540-253-5780.

Sandhill Crane and chick. Photo by Jo Crebbin, Shutterstock.

Sandhill Crane and chick. Photo by Jo Crebbin, Shutterstock.

We have hope for the future for birds, thanks in part to American Bird Conservancy’s Legacy Circle — a special group of our supporters who have included ABC in their estate plans. Their commitment to our mission will help protect wild birds and their habitats for years to come. Will you join them?

P.O. Box 249

The Plains, VA 20198

abcbirds.org

540-253-5780 • 888-247-3624

In winter, Canada Warblers can be found in the Mindo Region of Ecuador. Photo by Owen Deutsch, www.owendeutsch.com.

In winter, Canada Warblers can be found in the Mindo Region of Ecuador. Photo by Owen Deutsch, www.owendeutsch.com.

The Antioquia Brushfinch (left), a yet-to-benamed antpitta, and a view of their new reserve. Photos by Santiago Chiquito.

The Antioquia Brushfinch (left), a yet-to-benamed antpitta, and a view of their new reserve. Photos by Santiago Chiquito.

Wood Thrush by William Leaman, Alamy Stock Photo

Wood Thrush by William Leaman, Alamy Stock Photo

by Rebecca Heisman

by Rebecca Heisman

Waimea

KAILUAKONA

Saddle Road

Ka'ohe Restoration Area Palila Forest Discovery Trail

Kaulana Manu Nature Trail

Palila (below) by Aaron Maizlish, Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. View of the Palila Forest Discovery Trail (bottom) by Mike Parr.

Pu'u 'O'o Trail

Waimea

KAILUAKONA

Saddle Road