GRADUATION Spring 2024

EDITOR’S NOTE

Welcome to the fourth and final issue of Xpress for this academic year! The last ten months have been a lot. With enrollment down close to 20%, budget cuts near $11 million and incoming students facing a 6% tuition increase each year for the next five years, finances have been at the fore. And yes, San Francisco’s cost of living continues to remain among the priciest in the country.

Activism continues to play a pivotal role on campus. Last year’s graduation cover showed student protesters at a Turning Point USA event. This year, we tried to avoid a protest cover. But both students and faculty alike have been taking a stand and advocating for change. In the fall, there were protests against the tuition hike followed by student unions and the California Faculty Association rallying for improved benefits within the California State University system.

By late April, SF State students joined a nationwide student walkout calling for a ceasefire in Gaza. But unlike many campuses, SF State’s protests have been different. So far, we’ve avoided violence, police interactions, and a canceled graduation. There have been teach-ins and a sense of community, but the summer looms and protesters remain determined to stay and achieve their four key goals: disclose, divest, defend, declare. Graduates are entering the workforce and so-called real world at a historic time. We’ve made it through Covid, a year of protests, and are now headed toward a politically heated election. What we’ve lived, experienced and learned here at SF State matters—for us and for the future.

— Giovanna Montoya, Editor-in-ChiefSTAFF

Editor-in-Chief

Managing Editor

Copy Editor

Content Editor

Visuals Editor

Engagement Editor

Designer

Designer

Writers

Photographer

GGX Contributers

Giovanna Montoya

Andrew Fogel

David Ye

Div Lukic

Tam Vu

Sydney Williams

Ella Lerissa

Devin Dean

Andrea Jiménez

Lydia Perez

Amy Burke

Gustavo Hernandez

Eva Ortega

Neal Wong

Sean Young

ON THE FRONT COVER

Alli Gator recently received a makeover, and has a variety of props they can use depending on the event.

ON THE BACK COVER

On April 29, SF State joined other colleges across the U.S. in setting up an encampment in solidarity with Gaza.

Welcome to Xtracurriculars

a video series highlighting San Francisco State students and their unique hobbies, passion projects and lives outside of campus. In a city as diverse as San Francisco, it only makes sense to showcase some of the wide-rang ing interests of our student body.

This first episode follows SF State student Erick Mayen Perez and friend, roommate and collaborator, Luke Gonzalez. The two sophomores spend most of their hours outside of class in their kitted-out bedroom studio playing and recording high-energy, fuzzy rock music for both of their solo projects— Ph3romon3s for Perez and Heavy Bev for Gonzalez— as well as their three-piece band Cannonmouth.

This second episode follows M.E. Murphy and the new generations of Bay Area skaters who are dismantling some of the unwritten macho rules about what skating historically must be and who was allowed to do it. As a skateboarding teacher for young kids, she teaches them that contrary to what you may have heard at skateparks 20 years ago, girls can indeed skate. The third episode follows Benjamin Ho, a studio arts major who has been making jewelry for almost ten years. His main focus is rings pressed from coins sourced from countries all over the world.

Scan the QR Code to get to our YouTube page and check out the videos.

– Div Lukic

with

Aspirations across time and space

High, how are you?

Remembering culture through ritual New student groups organizing for change

Are you feeling poetic?

Make your voice heard

What album is your vibe?

How do you spend a Friday?

What movie is playing in the background?

How do you take your coffee?

Take this quiz to find

What time are you out until?

What

are you going to?

For over 55 years, SF State has been a hub of efforts to reform education, with students, faculty and the greater campus community actively participating in strikes and protests for decades.

In November 1968, students from the Black Student Union and the Third World Liberation Front began striking in response to the suspension of George Murray, a teaching assistant and member of the Black Panther Party. Ann Robertson was a graduate student at the university, then called SF State College, when the strike began.

“I come from a background where my family wasn’t political at all,” said Robertson. “So all of this was incredibly new to me.”

Most of Robertson’s classes were canceled, but one of her philosophy professors did not participate in the strike, so she attended his class.

“I was more on the sidelines, just beginning to get politicized myself,” said Robertson. “But when I came back [to teach at SF State], I actually had a very good relationship with most of the faculty in the philosophy department. When I was a student, I was kind of critical of them for not being more radical.”

Robertson’s politicization ultimately led her to become involved with the California Faculty Association, the union that represents around 29,000 professors, lecturers, librarians, counselors and coaches at all 23 CSUs.

Before the CFA was established statewide, the American Federation of Teachers was the union representing faculty at SF State.

Arthur Bierman, co-founder of the SF State AFT chapter, wrote a letter to the San Francisco Bay Guardian in December 1968 stating that SF State was in crisis, despite the image then-interim university president S.I. Hayakawa and his administration presented.

“The workload at [SF] State is 50% higher than comparable colleges in other states; instructors’ pay is 20–30% lower; instructors have no contract; and the Academic Senate’s decisions have been violated frequently at will by the chancellor and trustees,” Bierman wrote.

On Jan. 6, 1969, the AFT went on strike—over 350 teachers formed a picket line near the entrance of the campus at 19th and Holloway Avenues to prevent students from going to class by crossing the picket line.

SF State’s legacy of activism: decades of struggle for education reform

1968–1969 strike shares several similarities to recent strikes by CFA

Storyby Sean

YoungPhotography Courtesy of University Archives Design by Ella Lerissa

“The union was sympathetic to the Black students,” said Bierman in an interview in 1992. “The main reasoning along these lines was that the thirdworld people were not going to escape their lower position in the economic scale and acceptance into society unless they got themselves educated.”

Robertson added that alongside the support and solidarity for the Black Student Union, the AFT was concerned about possible legal repercussions for striking as state law prohibited state employees from striking or using collective bargaining.

The AFT demanded SF State administration settle the 15 demands of the BSU and TWLF and establish rules for faculty involvement in decisions around unit and class assignments and amnesty for all faculty, students and staff who participated in the strike.

Mark Allan Davis, CFA-SFSU racial and social justice representative, emphasized the critical importance of faculty unions engaging with students to tackle their demands and that students are just as fired up and engaged now as they were in the 1960s.

“Tuition hikes, the war in Gaza, the attack on [Critical Race Theory] and LGBTQ+ rights—all of it is right for students just as much as it was back then to organize and participate and engage,” he said. “We wouldn’t have had such a successful December 5 strike on this campus if it wasn’t for the support of the students.”

Davis noted one main difference: students and faculty in the 1960s faced issues that were more at the forefront. At the same time, today’s campus community deals with more distractions that prevent them from tackling as many issues.

“Students shouldn’t have to pay tuition because education is a public good,” said Robertson. “The entire society benefits when people are welleducated, so it makes sense to help society pay for it, not the individual.”

The AFT quickly reached a tentative agreement on Feb. 25, 1969, which the union approved on March 2.

The faculty returned to work two days later, with provisions to dismiss disciplinary actions against faculty members who participated in the strike, funding and staffing for the Department and School of Africana Studies, now the College of Ethnic Studies.

Though the faculty was able to get most of their demands met by SF State administration, the AFT failed to settle the demands set by students. The BSU and TWLF continued to strike until March 21, 1969, reaching an agreement after 133 days.

Robertson noted several parallels between the AFT and CFA strikes. Still, she believes that solidarity between faculty and students was stronger in the 1960s and that today’s faculty and students are looking to rebuild that strong alliance.

“It’s real power. That’s where our power comes from—it comes from acting collectively,”Robertson said. “Because if we’re all doing something together, which we’ve decided on democratically, we can begin to control what happens at the university.”

Radical Roots: Community in the Punk Scene

924 Gilman Street helps redefine the understanding of a community space.

by Andrew Fogel

As an offshoot of the rock and roll of the ’50s and ’60s, punk music and culture was created to challenge musical and societal standards. The music is raw and riddled with political messages of anti-authoritarianism, anti-consumerism and the recognition of class struggle. These traits could be seen in the community that developed around it—punks are loud, dress differently and can come off as intimidating. While this perspective permeated the mainstream, the message behind their musical and fashion statements was one of inclusion and the recognition of society’s wrongdoings. 924 Gilman Street is a classic punk venue in

Berkeley where bands like Green Day, Operation Ivy and Rancid grew in popularity, and is entirely volunteer-run. Although it’s been around since the ’80s, Gilman still upholds many of the tenets found in the punk scene when it was first created. Along with the political messages plastered in the building and the lyrics of the songs that reverberate off the walls, Gilman provides an all-inclusive space to the community. It is an all-ages venue that doesn’t tolerate racism, transphobia, abuse and any other traits that harm the community. In a world that seems so isolated, an inclusive community space is inherently radical.

¿ Soy realmente latino?

Como el español influencia el sentido de la identidad latina

Story by Eva Ortegaby Tam Vu Design by Ella Lerissa

Alrededor de 16.5 millones de Latinos están viviendo en los Estados Unidos desde el 2021, representando aproximadamente el 19% del país. Algunos han inmigrado a los Estados Unidos, otros han nacido de padres que lo hicieron y algunos más provienen de un linaje que ha residido en estas tierras desde que fueron anexadas de México en 1848. Todos ellos tienen raíces en una gran variedad de países, cada uno con sus propios valores y cultural. Para muchos, sólo hay una cosa que los une: el español que hablan.

El término “foreign language anxiety” se refiere a emociones negativas, como nerviosismo o aprehensión al utilizar una segunda lengua. En el aula, los estudiantes que experimentan este temor faltan a clase o no hacen la tarea para evitar las emociones negativas que surgen de ellos, según un reporte publicado en la Revista de Lengua Moderna.

Ana Luengo, profesora y coordinadora del programa de español de SF State, brinda una educación “muy individualizada” a sus estudiantes porque a menudo vienen a clase con diferentes niveles de español.

“Muchos estudiantes tienen complejo al hablar el español porque sienten que no lo pueden hablar bien”, dice Luengo. “Yo como profesora lo que quiero es que mis estudiantes puedan salir con una formación académica que les permita conseguir buenos trabajos”.

Este concepto de ansiedad se ha vuelto más prevalente con la aparición del fenómeno “No Sabo”. Esta frase ha ganado popularidad en el internet, para referirse a los latinos que hablan español incorrectamente, como decir “no sabo” en lugar de “no sé”.

“La mayoría de niños y niñas de la comunidad latina hablan sobre todo español, hasta que llegan a la escuela y por la violencia que reciben, por la discriminación lingüística, abandonan el español. [...] En cualquier caso, ridiculizar a cualquiera por como habla una lengua es muy violento”.

De hecho, el 54% de los latinos que no pueden mantener una conversación en español dicen que otros latinos les han “hecho sentir mal” por no poder hacerlo, según un estudio del Pew Research Center.

“Sé que se ha convertido más bien en una broma cultural, pero también es muy degradante, especialmente considerando la inmigración masiva a los Estados Unidos y la gente que intenta asimilarse”, dijo la estudiante Vanessa Muniz. “Esto ha resultado en que la gente no tiene la accesibilidad para seguir hablando, aprendiendo y enseñando español”.

Aún así, las conversaciones sobre el español y su conexión con la identidad latina no toman en cuenta la complejidad de las experiencias de quienes lo hablan.

Joseph Escobedo no entiende por qué los latinos se están criticando si el idioma difiere mucho de un país a otro. Como alguien de ascendencia peruana, su español a menudo no coincide con el que hablan sus amigos mexicanos.

“¿Cómo se dice ‘corn’ en México?” Escobedo pregunta. “Dicen maíz, pero ‘choclo’ es lo que se usa [en Perú]. Así que todos tienen sus propias palabras. Hay diferencias culturales entre los latinos entonces ¿por qué los estamos comparando? Que otros latinos te echen eso encima porque no eres tan ‘latino’ como a ellos les gusta, se siente peor. Te hace sentir como un extraño en tu propia comunidad”.

Escobedo, quien tiene la bandera peruana tatuada y lleva joyas y diseños para reflejar su orgullo cultural, dice que decidieron reconectarse con sus raíces después de ver lo distante que estaban sus hermanos de ellos.

El estudiante Leonardo Meza Martínez, quien es de Aguascalientes, México, no está de acuerdo con la idea de que alguien sea “menos” latino por no hablar español. “No deben de tener vergüenza y no les debe importar lo que la gente piensa”, dice Meza Martínez. “Practícalo, inténtalo, vas a cometer errores y te digo desde la perspectiva de alguien que estuvo intentando aprender chino-mandarín e inglés. He tenido ese temor, ese sentimiento, así que mi consejo es tener el valor para hacerlo”.

El estado de California espera tener 3 de cada 4 estudiantes “competentes” en al menos dos idiomas para 2040. Sesenta y dos escuelas dentro del Distrito Escolar de San Francisco ofrecen recursos educativos multilingües, por el Departamento de Educación de California.

La profesora Luengo cree que estas iniciativas podrían tener matices problemáticos.

“Muchas de las escuelas bilingües de inmersión no están pensadas para la comunidad latina porque están pensadas en barrios que son bastante privilegiados y donde acaban yendo niños y niñas que no son latinas” dice la profesora Luengo. “Eso es lo que me preocupa, que las familias latinas no potencien más ese capital [cultural]”.

En otras palabras, los estudiantes cuyas familias han emigrado recientemente están recibiendo una educación basada en dejar el español mientras que los demás se están volviendo en “ciudadanos bilingües que puedan ser competitivos en el mercado”.

Si bien esta dinámica continuará en los Estados Unidos, hay quienes seguirán resistiéndose a las connotaciones negativas asociadas con no hablar español con fluidez.

“El hecho de que alguien me diga algo no significa que sea un reflejo de mí”, dice la estudiante Jess Carranza Montoya. “Sé que hago lo mejor que puedo para conectarme con mis raíces. En realidad, ni lo intento, estoy comprometida—comprometida a conectarme con mis raíces”.

Clarity inCHAOS

Exploring ADHD: one of the most common learning disabilities in the U.S.

Story by Sydney Williams

In the crowded, fast-paced walkways of SF State, Cordy Walker, a firstyear cinema major, feels like his world is moving at a different pace than everyone else’s. Classmates around him easily understand class lessons and assignments, while he feels he has more homework than anyone else in the class. As classrooms buzz with activity, his mind jumps from one distraction to the next and he struggles to get back on task.

As the deadline for a procrastinated assignment gets closer, the clock begins to tick faster and louder. For someone with Attention Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder, staying focused, organized and on task feels like a constant internal battle. Daydreaming out the window, Walker forgets about his long list of tasks. Knowing that there are things that need to get done, guilt and regret come rushing in, but Walker just can’t focus—and neither can 8.7 million other adults around the world.

ADHD is one of the most common learning disabilities in the U.S. At SF State, about a third of students registered with the Disability Programs and Resource Center have ADHD, according to Roberto Santiago, the DPRC associate director. It affects people in different ways, and the diagnosing process also can vary depending on several factors and the student. ADHD can be particularly disruptive for students and has also been correlated with lower graduation rates and grades according to the National Library of Medicine.

Walker excelled in the classroom throughout elementary school, but the academic pace and workload became increasingly overwhelming when transitioning into middle school. Throughout high school, Walker continued to show symptoms of ADHD and, with the help of his teachers, he was able to take the first steps in the diagnosis process.

“I got diagnosed in freshman year of high school, and I remember we had meetings with all my teachers because I was not doing well in school,” said Walker.

Diagnosis

Unlike other disorders, there is no medical, physical or genetic test for ADHD. The process of being diagnosed also differs depending on the person and depending on the doctor. The most common route to diagnosis is through a diagnostic evaluation that can be administered by a mental health professional or physician. They also gather information from those close to the patient about their behaviors and tendencies.

The behavior and symptoms of the patient can change day to day, week to week or month to month, leading to the possibility of inconsistencies in the responses from the diagnostic questionnaire, according to Mary Requa, Mild Moderate Support Needs program coordinator at SF State.

“The assessment process for ADHD is rather subjective, and there is no brain scan—no medical test that you can conduct to determine definitively,” said Requa.

There are two different kinds of ADHD: hyperactive and inattentive. Some symptoms of hyperactive ADHD are seen through constant fidgeting, disruptive behavior, talkativeness and impulsiveness, while inattentive ADHD consists of forgetfulness, disorganization, making careless mistakes and constantly changing tasks. Both forms of ADHD present themselves differently, though they do share similar traits: poor time management, random and evolving hyperfixations, boredom and trouble focusing.

According to Requa, men are more likely to show symptoms of hyperactive ADHD, which is the easier of the two to detect, while women are more likely to present symptoms of inattentive ADHD.

“Women, typically in elementary years, are identified as the inattentive type,” said Requa. “The inattentive type is the quiet, well-mannered, gets her work done and, to a certain extent, doesn’t cause any trouble. There’s no attention being brought to those women or those young girls, so they are not identified with ADHD until very much later on. In fact, the teachers would say, ‘Oh, she’s so well behaved and she’s never a problem.’ ”

ADHD is often paired with other disabilities. According to the CDC, about half of children diagnosed with ADHD have a behavioral problem and about three in 10 children with ADHD also have anxiety.

Brendan Shrieve, a fourth-year business administration major at SF State, was diagnosed with ADHD in high school. He showed symptoms of both ADHD and depression.

“Sometimes I would be the one cracking jokes; other times I just have my hoodie on, headphones, and just [try not] to talk to anyone or do anything,” said Shrieve. “It definitely got a lot harder to get schoolwork done and focus.”

Taking on ADHD and depression was a battle for Shrieve, but he ended up figuring out different methods to succeed. Taking notes and writing everything down calmed his mind from jumping back and forth.

Medication

Since the COVID-19 pandemic and the use of online medical services like Telehealth, there has been an increase in ADHD diagnoses in the U.S. Doctors relaxed the rules and requirements around prescribing ADHD medications, making it hard for pharmacies to keep up with the new demand, according to Kyle Davis, a pharmacist who graduated from UCSF in 2006.

The increase of prescriptions has led to an ongoing and indefinite medication shortage. It has affected almost all patients and pharmacies nationwide.

“The reason behind it is because of the [Drug Enforcement Agency] and the limits that they are putting on manufacturers to be able to produce drugs that have these ingredients in them,” said Davis. “What that’s done is created a huge bottleneck in being able to produce the drugs themselves. Everybody basically is ordering a lot more of those drugs—all the pharmacies—and that’s causing allocations and backorders.”

Davis said that he only gets shipments of 20 milligrams of Adderall—the most common prescription for ADHD—every three to four weeks. When a patient can’t get their medication, they often have to search for other ways to tackle their symptoms.

“When I turned 18, my prescription disappeared and I have been trying for months [...] to get it re-prescribed,” said Walker. “When there was a Concerta shortage, they switched me to Focalin. But, every time I would try to call Kaiser, there would be a million transfers and then [I] end up at the wrong place and then just have to start all over.”

The ability to use Telehealth and video appointments to be diagnosed and prescribed medications is going to expire in 2025. Patients will have to return to in-person doctor appointments.

Accommodations

Juggling the academic workload and responsibilities outside of the classroom is often a difficult task for someone who has ADHD. It’s easy for someone with ADHD to lose focus on school and get caught up in current hyperfixations.

“I feel like the most difficult part about school was outside the classroom, doing work because I have terrible executive dysfunction issues,” said Walker. “So I feel like in the classroom, I’d miss things a lot of the time probably.”

The DPRC can provide specialized accommodation plans through self-reporting to help and best support the student. The center offers a variety of accommodations for students with ADHD such as a quiet testing area, time-and-a-half if needed and a variety of notetaking devices that will help the student remember what was taught in class. There are 861 students registered with ADHD at the SF State DPRC.

“So, trying to isolate what the accommodations are can be a tricky thing, because students have multiple eligibility,” said Santiago. “What’s more common is students come in and they don’t have documentation with them, and we say ‘Okay, here’s what we’re gonna need from your provider.’ ”

Nicholas Orgera, a third-year urban studies and planning major at SF State, was diagnosed with ADHD in fourth grade. During his freshman year of college, he registered with the DPRC, however, Orgera ultimately decided not to re-register during his sophomore year. Although the accommodations were specifically to help with his ADHD, he didn’t find himself needing them.

“I didn’t reach out to my teacher specifically for any accommodations,” said Orgera. “I think [accommodations] were [helpful when] I used them, but I just didn’t end up needing to use them that much.”

Although ADHD presents challenges for students, it’s important to recognize that it is not a limitation. The increasing awareness, understanding and support of people with ADHD is helping to foster a more positive environment where they can thrive without feelings of judgment or self-doubt. Finding a community of people who share similar experiences as someone with ADHD allows someone to feel less alone.

“The community that you’re able to find with people with similar experiences and just [the] understanding of things being difficult,” said Walker. “I feel like I’m not as judgmental because I’m like, ‘Who am I to judge?’ ”

A Certain Strain of Wrestler

This Oakland league returns wrestling to its roots

by Gustavo Hernandez

Before the establishment of some of the most renowned wrestling companies like World Wrestling Entertainment and All Elite Wrestling, theatrical wrestling could be seen in a more local setting. As the sport grew in popularity and companies merged, independent leagues fell out of the limelight—but many still remain. Situated in the heart of West Oakland is a wrestling league that brings the historic sport of entertainment wrestling back to its roots—with some herbal additions. Wrestlers of all skill levels meet at Stoner U

three times a week to learn, train, compete and often smoke marijuana together. Derek and Dustin Mehl, also known by their ring names Scott Rick and Rick Scott, have immersed their lives in the world of wrestling for over a decade. The walls of the warehouse where the brothers train students are teemed with vintage bobbleheads, event flyers and photographs of the theatrical sport. Stoner U is not only the perfect launch pad for anyone interested in the sport, but also pays homage to the early days of entertainment wrestling.

From the Bronx to the Bay: The journey of a history lecturer

Carlo Corea’s story as a college educator while managing job security

Story andphotography

by Neal Wong Design by Devin DeanAt the beginning of every class, students are greeted with “Joy, students, joy!” in the booming New York accent of Carlo Corea. The use of phones, laptops and other devices is banned in his classes, encouraging students to watch him as he enthusiastically talks about history.

Corea, who holds a doctorate in history, has been teaching the subject at SF State since 2003, but was only teaching one course last semester. Due to possible layoffs, he was unsure if he would continue to be on campus.

My understanding is I may not be here next semester,” said Corea. “I love what I do; it’s not a burden, it’s not difficult. I don’t get up in the morning and say ‘I don’t want to go to my job.’ I absolutely love it.”

Corea said he has an affinity with students who are the first in their families to attend college.

Born in 1965, Corea grew up in the Bronx. Neither of Corea’s parents went to college or finished high school. His father was an immigrant from Italy and his mother grew up in difficult circumstances.

“That was a kind of working-class world that I grew up in, so most people that I grew up with were not going in the direction of college,” Corea said. “In fact, they didn’t know much about it at all, and neither did I.”

Corea started working as a gas station attendant when he was 11 years old.

“That was my first job, then I started to do things like construction […] I did wallpapering and painting. I’ve worked in a horse farm,” Corea said. “I did all kinds of strange and unusual jobs that I thought were going to be very interesting and sometimes they were, sometimes they weren’t.”

He worked every summer and saved as much as he could, but in middle school and high school Corea was struggling.

“I was inattentive because I was a bit of a troublemaker. I really loved school, but I wasn’t good at school,” Corea said. “Middle school was horrible. There was a lot of drugs. There was a lot of violence.”

Because of these circumstances, community college was the most viable option for him.

“I took courses in everything, principally because I had no direction,” said Corea.

After two years, he transferred to the State University of New York at Albany, where he received a bachelor’s in history and political science. He then spent a year earning his secondary education teaching credential.

Corea spent all the money he’d saved from

working to buy a plane ticket to Europe. He was trying to replicate the Grand Tour: an educational, multiyear trip that young wealthy European men took in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries to complete their education.

“I couldn’t afford a train pass,” said Corea. “They had something called Eurail, I couldn’t afford that; I hitchhiked everywhere.”

After returning to the U.S., he resumed his education to get his master’s degree at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. There, Corea became a doctoral candidate with Matthew Jacobson as his advisor. Jacobson is currently a Sterling professor of American studies and history and a professor of African American studies at Yale University.

“Carlo was one of my first graduate students and one of the most memorable,” Jacobson told Golden Gate Xpress in an email. “He was thoughtful, insightful, intellectually generous, whip-smart, and deeply engaged. He was also very resourceful. I remember that for his project on race, ethnicity and the juvenile delinquency apparatus. He actually went to court to have some early twentieth-century documents unsealed. And he won.”

On Corea’s teaching skills, Jacobson had nothing but kind compliments.

“Even in Carlo’s earliest teaching assistantships he was already proving himself a gifted teacher— gentle in demeanor but exacting in his intellectual rigor, kind, expressive, funny, and generous with his time and energy,” said Jacobson.

After Corea defended his doctoral dissertation in 2001, he briefly taught at CSU East Bay but started teaching at SF State three years later.

When he was an undergraduate student, he didn’t feel supported and rarely talked to instructors. As a teacher of undergraduates now, he believes it’s important to establish one-on-one relationships with students.

He strongly encourages students to visit him during office hours, which he provides four to five days a week, even offering tea and cookies to those who do.

Two of those students are Mayuu Kashimura and Emily Fletcher. They’ve both taken two courses taught by Corea: HIST 120 and HIST 471.

“Dr. Corea’s ability to connect several smaller historical events into overarching narratives is very compelling,” said Kashimura. “His enthusiasm for history is infectious, and you can tell he really cares about his students.”

Fletcher said that Corea’s ability to connect historical and current events helped her understand U.S. history—a topic she struggles with.

“He challenges you to think and doubt anything you may previously have believed,” said Fletcher. “It is perhaps anxiety-inducing but completely keeps you on your toes and leads you to make rational, factual decisions.”

This article, originally published in Fall 2023, was edited for length. Corea is now teaching HIST 121. You can find the full version at goldengatexpress.org.

Spark in the Park Spark in the Park

A decades-long tradition continues despite attempted cancellation

Story by Giovanna Montoya

Story by Giovanna Montoya

Nestled between Haight Street and the Conservatory of Flowers lies the historic Hippie Hill. Surrounded by tall shady trees and refreshing green foliage, the hill overlooks Robin Williams Meadow and is a perfect place for picnics, basking in the sun and, on occasion, live music.

Although it was a perfectly sunny day, a thick layer of haze lingered over San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park on April 20. No, Karl the Fog was not paying the park a visit, and no, your glasses were not smudged. The mystical haze was simply caused by the celebration of a holiday that began right here in Northern California: 4/20.

The park became a landmark location after the 1967 Summer of Love counterculture movement. Each year, tens of thousands of cannabis lovers gather at Hippie Hill for the unofficial, unsanctioned annual 4/20 celebration. Unfortunately, for smokers, this year’s official event was canceled due to city-wide budget cuts and the diminishing cannabis market. But, the “cancellation” was no match for cannabis-loving San Franciscans, who made sure the park was anything but quiet.

Densely packed together, hundreds, if not thousands of people relaxed across picnic blankets, participating in friendly exchanges. With rolling trays in their laps, they listened to the enchanting music coming from one of the multiple community drum circles around the park. The pungent aroma could

be smelled for miles amidst those passing around bongs, pipes, blunts and comically large joints. While the recreational use of marijuana has been legalized in the state of California, it is still not legal federally, and Hippie Hill is in a federal park. So how is this possible?

For years, the city of San Francisco contemplated how to put an end to the events at Hippie Hill. Former Mayor Ed Lee told CBS News that they ultimately came to the realization that prohibiting 4/20 celebrations at the park would likely result in the dispersion of multiple events, making it even harder to regulate. In 2017, a year after the legalization of marijuana, the city begrudgingly decided against punitive enforcement and worked with organizers to permit the event.

Acquiring a permit for an event of this nature requires a couple more steps than it usually would. The Office of Cannabis normally handles marijuana-related permits. However, according to The San Francisco Standard, organizers of 4/20 at Hippie Hill needed additional approval from the San Francisco Recreation & Parks Department, the Departments of Health, both juvenile and adult probation departments and the SF Municipal Transportation Agency.

Considering SF State is a federal campus, students who live on campus don’t particularly have the option to celebrate from the comfort of their homes. Hippie Hill offers an adventurous alternative experience.

Angel Hancock puts a large joint up to his lips.

An Aries Distribution employee fans out his blunt wraps.

Angel Hancock puts a large joint up to his lips.

An Aries Distribution employee fans out his blunt wraps.

Exploring the Factors and Impact of SF State’s Declining Enrollment

President Lynn Mahoney discusses the future of the university

Story by Amy Burke by Tam Vu and Andrew Fogel LerissaEnrollment is drastically decreasing across many California State Universities, including SF State. The university has seen a reduction in enrollment over the past five years for full-time. There has been a 20% reduction this past year alone, and this trend isn’t expected to slow down.

With the cost of living in the Bay Area, ramifications from COVID-19 and students dropping out at a higher rate, the big question is: how will SF State adjust to these diminishing numbers?

“For the last five years [CSU] enrollment has gone down for incoming students, [...] especially first-time freshmen,” said Sutee Sujitparapitaya, the associate provost of Institutional Research at SF State.

President Lynn Mahoney explained in an interview that we must “embrace that we’re going to be smaller.”

Why are the enrollment numbers down?

There are a few reasons why SF State is seeing lower enrollment. One is that during the pandemic students moved back home to shelter in place. More often than not, when those restrictions were lifted students remained where they were. Two-thirds of California’s population lives in the bottom half of the state, contributing to the decreasing numbers at northern CSU schools. This has led to less attrition of student enrollment in some Southern California schools than Northern California schools.

Enrollment in community colleges has plummeted by 20%, according to Vikash Reddy, vice president of research at the Campaign for College Opportunity, a nonprofit focused on equity in higher education.

SF State isn’t alone in its declining enrollment; Mahoney explained that San Francisco City College and the San Francisco Unified School District have also been experiencing a decline in enrollment. SFUSD is down 10,000 students since 2015, and City College is down about 59%. These schools are some of the largest feeders to SF State and have maintained the health of the university’s enrollment for years.

Community college populations are vastly important to the CSU system, making this a state-wide problem.

Another important factor in the decline of student populations is the cost of living in the Bay Area. The high costs of rent, groceries and other necessities are punishing for students, which may influence the college decision for those outside of the Bay Area.

“There is little I can do about the cost of living in San Francisco,” said Mahoney.

The Bay Area job market is also a factor. According to Reddy, some students are dropping out to find high-paying jobs and putting their degrees on hold, which, in some cases, means never getting the opportunity to come back and finish. This allows them the time to make money to live here while gaining security with health insurance and higher salaries. Reddy points out that while this is a decent short-term solution, the long-term effects of salary ceilings and lack of advancement are often overlooked.

How will Mahoney pivot?

Housing

In response to the housing issue, the school plans to open a new residence hall next fall. The state has subsidized about 75% of the building costs, which helps the university’s financial burden. This allows the university to pass on savings to students through the Reduced-Rate Student Housing Program. The program, which will start next fall, will give first-year students a 25% discount on student housing across campus residencies.

She is also looking into new ways to help students who live off campus. Mahoney is seeking to generate philanthropic dollars from corporate and private sponsors that would help students with the cost of rent in the area.

Classes and Faculty Reduction

When asked how she plans to go from a 20,000+ student institution to a smaller one, Mahoney offered a few answers, including a smaller class schedule and severance payments to faculty.

“It’s actually shrinking our scheduled classes to match the number of students we have,” said Mahoney. “That’s not easy.”

She explained that these aren’t the budget cuts that students complained about this past spring semester, instead, it’s adjusting to the new number of students. The administration does predictive analysis of enrollment semester after semester, which aids in making decisions to create a smaller schedule before registration.

“First and foremost, [course numbers are] shrinking because it’s aligning the class schedule with the students,” said Mahoney. “That’s easy for me to say, but it’s hard to do.”

Mahoney recognizes that with change comes pain. SF State has had to lay off faculty as a result of these changes. The administration could not provide specific numbers on these job losses.

“I am mindful every time I talk about this that there are human beings whose lives are being affected,” said Mahoney. “But, at the end of the day, I have a fiduciary responsibility, and you can’t spend money you don’t have.”

The effort to condense the schedule is a process that involves the administration and the head of each department. It starts with each department building a schedule followed by administration matching that schedule with student numbers and the budget. Negotiations go on from there.

As part of the efforts to reduce the campus’s budget deficit, the administration is offering the Voluntary Separation Incentive Program, which allows faculty to resign with severance by June 30, 2024. The severance equates to 50% of the employee’s annual salary up to $75,000. Faculty who want to take this offer have to be eligible for retirement and have at least 10 years of service at SF State.

“We have set aside a certain amount of money,” said Mahoney.

The future looks smaller for SF State, but Mahoney thinks things can also be better.

“There’s no reason we can’t become smaller and better,” said Mahoney. “Our mission is really clear. For the most part, it is to service undergraduates and give them a transformative experience that leads to upward mobility.”

A Tentative Victory

The California Faculty Association’s fight for a fair contract

Storyby Andrea Jiménez

Photography by Andrew Fogel, Andrea Jiménez and Tam Vu

Design by Ella Lerissa

In June of 2023, the California Faculty Association union and the California State University system bargained for a new contract. The CFA has been advocating for staff and faculty labor rights for four decades. However, this was the first time regular union members were permitted to participate in contract negotiations.

The CFA represents nearly 29,000 professors, lecturers, librarians, counselors and coaches across all 23 CSU campuses, and has been doing so since 1983. The union fights for academic freedom, faculty rights, fair pay and improved spaces and learning environments on campus. What started out as a typical contract negotiation ultimately snowballed into the CFA leading the largest higher education strike in history.

Mark Allan Davis, the CFA Council for Racial and Social Justice representative, explained that the open bargaining process set this negotiation apart from previous ones.

“When they walked in and saw a room full of 75, 80 members, they were really terrified,” said Davis.

In the early stages of bargaining, the CFA brought their demands forward: a 12% salary increase across the board, a minimum wage

increase for the lowest-paid faculty, gender-inclusive bathrooms and safe lactation spaces, a counselor for every 1,000 to 1,500 students, a family leave increase from 30 days to one semester and safeguards for Black and brown faculty in police interactions.

“Normally, bargaining has been closed, which means that the bargaining team is operating separately from us. So, we don’t know what’s going on in the marketing—they just tell us,” said Davis.

SFSU-CFA chapter President Brad Erickson explained that in the past, closed bargaining had made it easier for the CSU to dismiss the union’s demands.

“They’re very comfortable talking behind closed doors […] because it is easier for them to bully and control and to say, ‘Oh, well, that’s not possible,’ ” said Erickson. “But when they do that stuff in front of an audience of workers, the workers see their bullshit and it angers them. That inspires them to act and to organize.”

In response to their demands, the CSU offered a 5% salary increase with no mention of raising the salary floor. After the two sides couldn’t agree on a contract, the CFA declared an impasse and voted to go on strike. The vote to strike passed with 95% in favor, and on Dec. 4, 2023, Cal

Poly Pomona, SF State, CSU Los Angeles and Sacramento State University participated in a rolling four-day strike.

On Dec. 18, the CFA Board of Directors unanimously voted to continue with a systemwide strike between Jan. 22 and Jan. 26. The CFA was willing to refrain from striking if the CSU was willing to negotiate their original offer. However, the two organizations failed to see eye to eye.

Tentative Agreement

On Jan. 22, the longest faculty strike in U.S. history was cut short. An email sent out to union members that night notified them of the news: the CFA and CSU reached a tentative agreement, but not the one some union members had hoped for. The tentative agreement then had to pass through a union member vote.

“People were disappointed,” said Davis. “Some people were confused like, ‘Wait a minute, what happened?’ ”

In the tentative agreement, the CSU offered a 5% general salary increase, retroactive to July 1, 2023, and another 5% increase this coming July. However, the second raise is contingent on whether or not the state reduces base funding to the CSU. The salary floor for the lowest-paid faculty would increase by $3,000.

Many union members felt blindsided by the CFA bargaining team’s decision to accept the CSU’s offer. According to Davis, despite the bargain being open, union members were left out of the final decision regarding the tentative agreement.

“It was coercive and bullying,” said Erickson. “If we’d been consulted, we might’ve even agreed to the TA and fight another day… But we were excluded from the conversation. That was the real bitter pill…the way it went down.”

On the Thursday that would have concluded the four-daylong system-wide strike, SF State hosted a rally in the Quad, protesting the agreement. Union members even formed a “NO” in the grass to express their disappointment. According to KQED, the SF State chapter polled 360 of its members; 70% of which said they planned on voting no, while only 3% planned to vote yes.

Despite the opposition from SF State, union members from CSUs across the state passed the tentative agreement with 76% of voters in favor of the proposal. Another opportunity to bargain for a contract will not be presented until 2025.

Erickson believes the TA passed because of misleading ballot language.

“Only 75% voted yes so that is a fivefold increase in no votes,” said Erickson. “That signals a crisis in confidence in the union leadership.”

Now, Erickson along with other union representatives are bringing forward resolutions during their general assembly meetings. The resolutions, if passed, would create more transparency between the main CFA and its members.

“Our goal right now is to try and dislodge those [disappointed] thoughts and to move forward more powerfully and positively,” said Davis. “It is in anticipation of 2025 to reorganize and make sure that our members know that they can participate, to make it understood very clearly that they should and can.”

History of Campus Unions

The students and staff that comprise SF State’s campus are no strangers to activism. The campus has been recognized for having the longest student-led protest in the U.S., lasting from November 6, 1968, to March 21, 1969, eventually leading to the establishment of the first College of Ethnic Studies in the nation. In the past year, SF State and the CSU system have made headlines once again, this time for labor rights movements. SF State has been at the forefront of unionization and fair contracts in the workplace. Here are some of the active unions on SF State’s campus:

California Faculty Association (CFA)

Founded: 1983

Who is represented: Over 29,000 CSU professors, librarians, counselors and coaches throughout the CSU system, with over 1,000 members represented at SF State.

The CFA’s role is to advocate and bargain for the needs of CSU staff including teachers, librarians, counselors and coaches. The CFA made headlines in December 2023 when they went on the largest faculty strike in the nation after the CSU system and CFA failed to see eye to eye on a contract. The CFA and CSU reached an agreement and passed a vote for a new contract in February 2024.

California State University Employee Union (CSUEU)

Founded: 2005

Who is represented: Support staff members of the CSU, which includes, information technology, healthcare, clerical, administrative and academic support, campus operations, grounds and custodial. Over 20,000 students and 16,000 support staffers are represented across the 23 CSU campuses.

While the CSUEU has represented support staff members since 2005, the union made history after student assistants voted to join the employee union in February 2024. This made the CSUEU the largest undergraduate student worker union in history. The students represented include student assistants, non-citizen students and work-study assistants across the CSU system.

Service Employees International Union-United Service Workers West (SEIU-USWW)

Founded: 1921

Who is represented: Sodexo employees who work in City Eats and Bricks. SEIU-USWW represents around 45,000 service workers across California.

SEIU-USWW has represented City Eats employees for over a decade. In early 2024 the union asked for the support of students on campus while they bargained for higher wages with their employer, Sodexo. City Eats employees successfully negotiated a new contract that included higher wages.

Teamsters

2010

Founded: 2010

Who is represented: Over 14,000 CSU electricians, plumbers, carpenters and other tradespeople.

In November 2023, the Teamsters 2010 union went on strike across all 23 CSU campuses to protest unfair wages and stagnant contracts.

The Union of Academic Student Workers (UAW)

Founded: 2004

Who is represented: 10,000 CSU teaching assistants, graduate assistants and instructional student assistants across all 23 campuses.

According to their website, the union works towards collective bargaining to ensure steady wage increases and benefits, provides student workers with their rights and enforces the contract with the CSU.

SF STATE’S MODERN ACTIVISM

We hold the signs, but where are they pointing?

Students protest the 6% CSU tuition hike. (Tam Vu/Xpress Magazine) Story by David Ye Photography by Tam Vu

Social change and activism thrive on many college campuses nationwide, challenging the status quo and igniting movements that extend far beyond campus borders. The past achievements of activism on college campuses is a testament that speaks to the power of young voices in shaping the future. That could be said for so many points in SF State’s history, whether it be the 1968 Third World Liberation Front strike or the recent Gaza solidarity encampment. One such occasion was when Larry Salomon and his friends, who had been exiled from South Africa because of racial segregation, invited Chris Hani, head of the South African Communist Party and the African National Congress’s paramilitary wing, to campus as a speaker.

“It was really one of those moments where you’re like, ‘Man, I’m part of something here,’ right?” said Salomon. “You saw yourself as not just an individual who can write a letter to Congress or write a paper about something or learn on your own and feel like you’re educated, but you had this connection to organizations that were actually trying to transform this stuff, to overcome it, to defeat it.”

Now a senior lecturer in the Race and Resistance Studies department, Salomon has noticed many trends and changes in campus activism. He described its current form as “quieter” and “apolitical.”

“That doesn’t mean that stuff’s not going on— it just means it’s not so visible on campus,” said Salomon.

So what does activism at SF State look like nowadays? Amidst so many societal factors and changes—the emergence of new identities and old wounds—what might it look like in the coming years?

DeMorié Okoro, a fifth-year student majoring in philosophy with an emphasis in law, is spearheading an effort to start a political committee within Haüs BlàQue, a Black, queer and transgender club at SF State. Okoro currently acts as a chairperson on the board of Haüs BlàQue. For them, starting the club was a matter of carving out a space dedicated to acknowledging the ways Black, queer and trans identities intersect.

“We still very much interact with [the Black Student Union] and [the] Black Unity Center; they come to our events, too, and it’s a beautiful thing,” said Okoro. “But to have our own space really feels a lot more uplifting.”

Haüs BlàQue is one of the three queer-ethnic student organizations that started last semester, with the other two being the Asian and Pacific Islander Queer and Trans Club and the Latinx Queer Club. Although Haüs BlàQue is the first of the three to have a political committee, each club is political in its own right.

“For me, at least, an apolitical safe space isn’t a very safe space because of just how intertwined everything is,” said Amatullah Zapanta-Mir, a first-year Race and Resistance Studies student and founder of the APIQT Club. “It’s like what people say: it’s not political, it’s just human rights.”

With the Students for Gaza encampment on the Quad, which started April 27, activism on campus is becoming more political. There will only be more presentations of activism to come as the world continues to see the need to take a stand, especially with the November general election bookending next semester.

“I know a lot of people will be starting new classes next semester, and they might meet new people and make new friends,” said Amey, a graduating cinema major and media liaison for Students of Gaza. “This is a place for people to learn, so it’s okay if you don’t know anything or if you don’t know a whole lot, but you’re sympathetic. Just ask people that are here and attend the teach-ins—you’ll learn a lot.”

In terms of the future of SF State’s activism, Okoro and Zapanta-Mir think there are enough people to keep things going, but they also recognize the need for more collective action.

“Last semester, I was really heavy on doing what I can to help on my own, but now I’m like, ‘I have to remember that community work is for the community to do,’ ” said Okoro. “I hope with me and other student organizers encouraging the younger generation to continue to be aware and advocate for themselves, it continues to uplift and improve and sustain. I have a good feeling about it.”

While Okoro’s and Zapanta-Mir’s clubs reflect an increase in the number of Americans who identify as LGBTQ+—21% of whom happen to be Gen Z, according to a Gallup poll—groups like the Black Student Union and the General Union of Palestine Students have been advocating on campus for over 20 years. But with new times comes new opportunities for equity, which is what the recently founded Southeast Asian Student Association hopes to provide.

“Within the Asian diaspora, Southeast Asians often go overlooked, and within our own community, certain ethnicities such as the Hmong and [Iu Mien] people still go unrecognized,” said first-year SEASA president Jennifer Belisario. “In the future, we hope that SEASA becomes a stepping stone toward better Southeast Asian representation in higher education and fighting the model minority myth to ensure that Southeast Asian students’ needs are met.”

Preserving Vietnam

Keeping Vietnamese culture alive in San Francisco 50 years after the war

by Tam Vu

San Francisco is home to a wide variety of different cultures and, although they may be hard to find, Vietnamese communities do exist. If you walk along Duboce Avenue, you may pass what looks like your normal, run-of-the-mill San Francisco home, but inside is a Buddhist temple called Chùa Từ Quang, locally known as the Vietnamese Buddhist Association of

SF. For decades, this temple has been a space for older members of the Vietnamese community to practice their spirituality and feel at home. Most of the regulars fled the Vietnam War and this temple provides them with a little piece of Vietnam. Almost 50 years after the war, the rituals and sense of community still stand today.

“My Country is my Abuela”: Q&A with Yosimar Reyes

Eight years after his graduation, the seasoned poet returned to SF State to discuss his journey since thenStory by David Ye Photography by Feven Mamo Design by Ella Lerissa

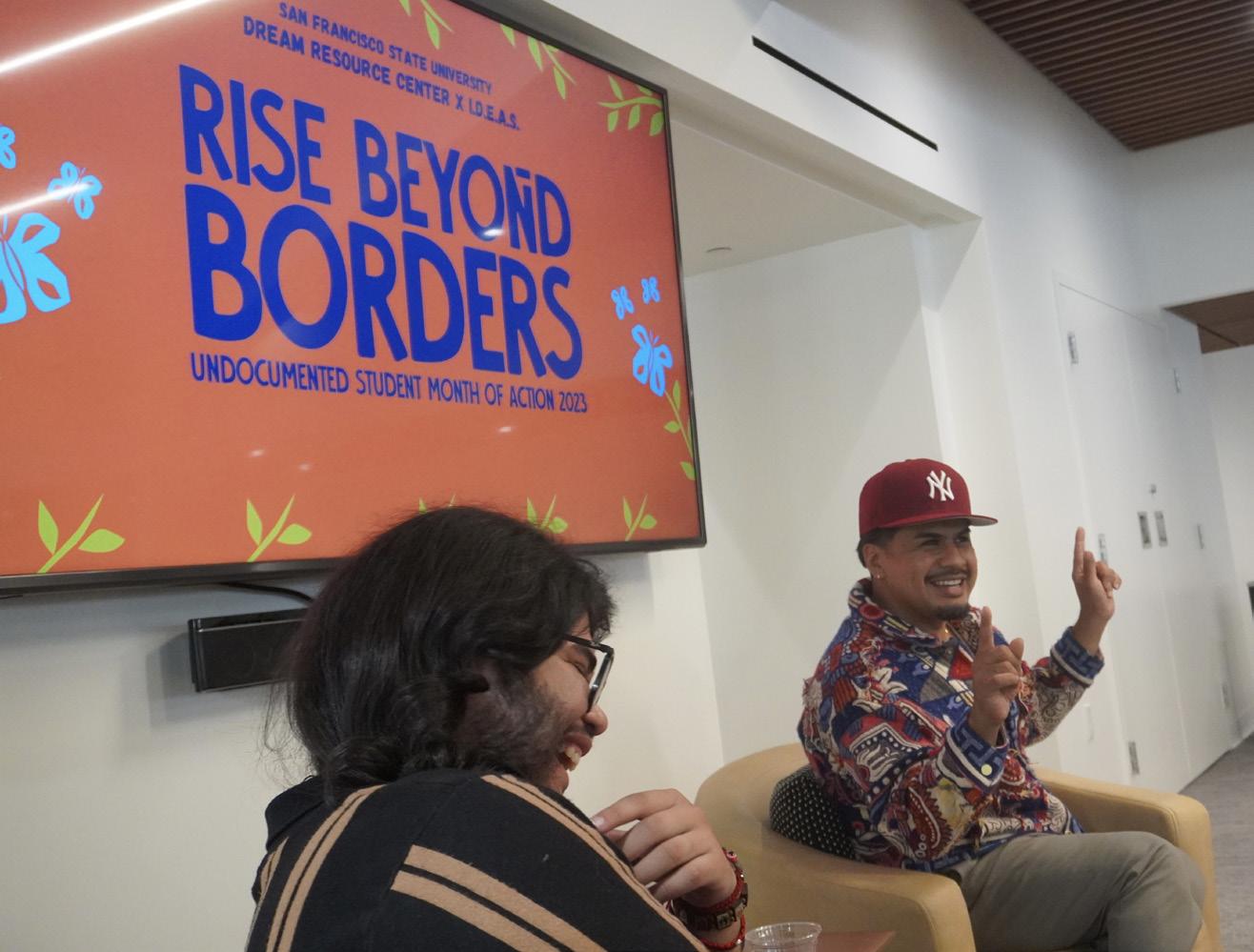

On Oct. 10, 2023, the Dream Resource Center and the student organization Improving Dreams, Equity, Access and Success welcomed back SF State alumnus Yosimar Reyes for an open panel, “Beyond Graduation: A Conversation with Yosimar Reyes.” The panel was the second event of the Undocumented Student Month of Action, a series of programs inspiring solidarity for undocumented students.

Born in Guerrero, Mexico, and raised in San Jose’s East Side, Reyes graduated from SF State in 2015 with a bachelor’s in English with a concentration in creative writing. Since his self-publication of “For Colored Boys Who Speak Softly” in 2009, Reyes and his work have achieved accolades such as an Undocupoets fellowship in 2017 and a Lambda Literary fellowship in 2018. Last May, he was named the first-ever Performing Artist in Residence at Movimiento de Arte y Cultura Latino Americana, a San Jose-based Latinécentric art center.

At the panel, which took place at the Cesar Chavez Student Center, Reyes spoke on his experience as a first-generation college student and some of the classes he took during his time at SF State, the over-saturation of “fear narratives” within Latinx literature and his future plans. He also read three of his poems: “Dirty,” “Undocumented Joy” and “Caldo de Pollo.”

From Oct. 20 to 22, Reyes performed staged readings of “Prieto,” his first autobiographical play, at the Chicago Shakespeare Theater as part of the city’s Latino Heritage Month.

How did you feel about being back at SF State?

It was good—definitely nostalgic. Every time I go to a college campus, I’m like, “Oh, I miss school, I miss how fun learning was, being around students,” all of that—I think it’s inspiring.

“For Colored Boys Who Speak Softly” was self-published—how did you end up in such a lucky position?

When I was 18, 19, I got the opportunity to meet Carlos Santana. He was donating money to the school that I was attending. They asked me to come read a poem for him. That poem ended up opening up his concert series that year, and obviously I was just excited to be a part of it, to be hanging out with him and to just be doing something really cool.

He was very generous with teaching me different things or just talking to me, inspiring me. Just for me to have access to him, I think it was really, really awesome. At 19, I think not a lot of people have that. And so he asked me what I wanted, how he could pay me for my work. I was like, “Dude, I want a book.” He was very generous in providing me with the financial backing to produce it. I would hustle these little books at my shows or my presentations. I was blessed enough that people found value in it.

Similar to how Javier Zamora wrote “Solito,” which is a memoir about his 9-year-old self’s trek from El Salvador to the U.S., you wrote “Prieto,” which you said in an interview with Shondaland, is a word which “means dark skin, or someone who’s dark.” What do you think about this cultural pattern of having native words for certain experiences and how despite their specificity, they promote cultural and ethnic solidarity?

I knew that I wanted to title my show one word and in Spanish. I wanted to have a deep R because “Prieto”—you have to say it, you gotta feel it like it’s a thing. I think that was important because it’s also a derogatory term that a lot of people use in Mexico because we have a lot of colorism. It represents who I am; I am a dark-skinned Mexican. I can’t help it and I want to own it.

“Solito” is a word that talks about being alone. All of that was very emblematic and I wanted to represent in that way. Also, I felt like one-word titles are very impactful because I was like, “Oh, what more is there to uncover?” I feel like my show—you hear the word “Prieto,” but throughout the show you find different definitions of what it is, and ultimately how I define it.

It’s a love letter to dark-skinned undocumented Mexicans or immigrants. It’s a love letter to all these people who are conditioned to believe they were ugly. There’s beauty in all of that. Uncovering all these definitions to that word—that’s the journey my show takes people on.

You turned 35 [in September 2023]—when you were an undergrad, did you ever think your life would turn out the way it did?

Not at all. Even now, I feel like I’m still building. I’m successful, but I would consider myself mid-career—I’m still not where I want to be. I get to travel around the country. I have a lot of amazing people that support me. I get to do a lot of cool projects, but I think my goal ultimately is to figure out how to establish myself as a well-known author. One of the things that I appreciate about my artistic journey is that it’s been gradual. It’s slowly progressing into what I want to do. I just gotta keep focused and be disciplined in my craft to achieve that.

OPolitical veteran and SF State alum shares his advice for students

WillieQ&ABrown

n the morning of March 20, former mayor Willie Brown awoke from his sleep, but this wasn’t any normal day—it was his birthday. An important part of the fabric of San Francisco, the spry 90-year-old was the city’s first Black Mayor and a decorated political veteran. He was a California State Assembly member, as well as its first Black speaker of the California Assembly. Throughout his career in California politics, he became known as a defender of civil rights for the LGTBQ+ community and a living example of discipline across the political spectrum.

Brown is also a proud SF State alum. After graduating in 1955, he went to law school at UC Law San Francisco. He was also involved in civil rights advocacy and was a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Following his career, he founded the Willie L. Brown, Jr. Fellowship program, which places SF State students in local government internships.

Xpress recently sat down with Brown to discuss his experience in politics and his long and interesting life. This interview was edited for clarity and length.

a highlight, if not the best, because at that time, you are the mayor of a city with the authority and the power vested in the mayor of this city, by virtue of a vote of the people—you really ran the city, as if it was a company. And all of the people who were in other electoral positions were, in every manner, desirous of cooperating to make things really work. My candidacy and my performance was based on that. And that was a great joy because for more than 30 years, I had been a legislator. In [the] capacity of being a legislator, I had done lots of good things for the whole state, but nothing compared to being mayor of San Francisco.

What do you think the most difficult chapter has been for you?

I don’t think any task could be considered difficult, because I have virtually succeeded at all of them. So they clearly were not too difficult.

Why did you create the Willie Brown Fellowship?

I created something that I thought would afford the opportunity for people at SF State, who may have just a fleeting interest in public service, to become a true public servant, either through the electoral process or through helping somebody get elected, and then ultimately serve in through the appointment process on a board or commission, or through the process of doing a civil service and becoming a part of the system.

How did you get interested in public service?

When I graduated from law school, it was a natural [transition], because I had done so many things while in college—the fraternity that I was a member of at SF State, Delta Omicron Alpha Phi Alpha, and then, of course, [my] membership in the NAACP Youth Council, of which I was national vice president. I was also in a theatrical performing company that was directed by [Judge] Joseph Kennedy.

A combination of all those things caused me to become acquainted with the Burton family. The Burton family was a family of the political types, and that caused me to really want to be a part of the public policymaking period.

Is being part of the scene what helps you get through the doors that would normally be very challenging to get through?

Well, I think the whole business in that day and age of going to college was a big, big thing, particularly when you go to a four-year college. Most of the people that I knew in San Francisco initially went to the City College of San Francisco, out in the Ingleside area, and only a few went to the four-year institution out there, or the four-year institution over in the Richmond [District], part of San Francisco, called USF. The ones that went there were the athletes, basketball players. The people who went [to] SF State were the veterans who had the GI Bill to support their being in college. Only a few of us were actual high school graduates going into school beyond high school for the first time. So it was an interesting way in which I made the transition from high school, ultimately, to graduate school.

How did it feel to be the first African American mayor of San Francisco?

It was quite an honor and I still accept it as an honor. But it was a great challenge because I defeated an incumbent former police chief for the city. And [20 years ago,] the city was almost as unresponsive as it has been since the pandemic.

So you’ve had a very long and illustrious career. What’s been your favorite chapter?

Being the mayor of San Francisco, by anybody’s evaluation, would be

No such thing existed at the local level, and that gave me the opportunity to make sure that my successors, after eight years of being the mayor, would have available to that person—or those persons—over the years — quality staffers. And that’s what caused me to have the institute that’s associated with SF State. And it has been, frankly, quite productive for people who might want to do public service. And they get exposed to public service by actually working in some capacity in the city and county of San Francisco, in some department or some agency of their choice.

We hear a lot about the San Francisco doom loop. What’s your take on it?

Well, that’s all misrepresentation—a press misrepresentation mainly, and it’s interestingly enough national press misrepresentation, because our local press is virtually not current, so to speak. You now know that the stories you’re reading in San Francisco are already three days old.

Mayor Breed has talked about her big plans for downtown San Francisco and the Black to San Francisco initiative. How would you like to see SF State integrated into the programs she’s talked about for historically Black colleges and universities?

I hope that San Francisco State will become a college with a downtown campus, similar to what has occurred in New York, and in Boston, and in Chicago, where campuses and college students have been much a part of this scene in a location. To the extent that students are part of the location, it ensures that the quality of life becomes influenced by the student body, so to speak, and especially if they can live within walking distance of their educational establishment.

How do you think we can attract Black students to come and then stay to graduate from the university?

There’s competition now from colleges, all over the country, for students. The cost of going to these schools are now pretty much dependent upon the student payment plans. It is clear, however, that whichever university or college comes forward with the most affordable opportunity for quality advancement in higher education, that’s what will attract the students, period, and that clearly, in the San Francisco Bay Area, includes where the student can live. The cost of living in San Francisco is very high.

What concerns you the most about the future of San Francisco?

I fear that we are not as open as listeners [and] as newcomers, as we once were. At one time, it was almost for certain that San Francisco’s population was constantly being flooded with new blood. That doesn’t seem to be as much of a quality now as it once was. I fear that that will hurt [San Francisco] ultimately.

The country is more divided than ever—what would you say to students about the state of politics as we enter yet another election season?

I would hope that students would adopt that kind of program and the kind of meeting of challenges, as I did from 1951–1958. At all times, whatever was occurring or needed to occur in the city during my educational years, we all as students adjusted to it. When you get students back to doing it that way, they could be of tremendous help in improving the quality of the people who ascend to the positions of influence and power. The execution of that, I think, would be productive for all San Franciscans.

What are your priorities right now?

Helping other people get elected to public office, and helping those who might already have the skills that are in public office to retain their position. People like Mayor Breed, people like Congresswoman Pelosi—people who are in those categories—need assistance in getting elected and re-elected. My priority is to see that my time is spent, to the extent I can, being of assistance in achieving their success.

What’s your favorite thing about San Francisco?

The people of this place makes every hour of the day worth being here.

How do you want people to remember your career?

I would hope they will see the productive side of my career, evidenced by the quality of people who seek public office and get elected to public office.

Is there anything else you’d like to say to the students of SF State?

Looking forward to a whole new crop.