The Ukraine War Edition

Special Companion to

Special Companion to

Everything You Need to Know About the History (and More) of a Region that Shaped Our World and Still Does

Everything You Need to Know About the History (and More!) of a Region that Shaped Our World and Still Does

“The problem is that history has never known where Russia precisely begins and where it ends. And there is a certain problem in this. Nevertheless, I am a champion not only of individual freedom but also of the freedom of nations.”

—retired Czech president and former communist-era dissident Vaclav Havel, 20091

“C’est pire qu’un crime, c’est une faute.”

(“It is worse than a crime; it is a mistake.”)

Antoine Boulay de la Meurthe, a legislative deputy in the French parliament, upon the execution of Louis Antoine de Bourbon, Duke of Enghien, on Napoleon’s orders, 1804 (often misattributed to French foreign minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand)

“Russia is Putin. Russia exists only if there is Putin. There is no Russia without Putin.”

Kremlin policy architect Vyacheslav Volodin, in a policy meeting at the Valdai Club in Sochi, Russia, November 20142

“Unwilling to rest on the foot of conscience, my Russia took a few big leaps, pushing everyone around, but then slipped and collapsed with a crash, destroying everything around it. And now it is floundering in a pool of either mud or blood with broken bones and the poor, robbed population, surrounded by the tens of thousands of victims of the most stupid and senseless war of the 21st century.”

—Russian dissident Alexei Navalny (1976–2024) in a statement in a courtroom before he was once again sentenced for political crimes, July 20233

1 “Transcript: RFE/RL Interview With Vaclav Havel.” (2009 March 27). Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty. Retrieved from: https://www.rferl.org/a/Interview_Vaclav_Havel_Global_ Crisis_NATO_Self_Determination/1563288.html

2 Zygar, 2016: p. 309

3 Алексей Навальный (Alexei Navalny). (2023 July 20). “‘Conscience and intellect’. Navalny’s last word in his ‘extremism’ trial.” YouTube. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=7NeQK9HJIvg

I cannot believe there is a war in Europe again. As a student in Hungary in the late 1980s and early 1990s with an apartment on a small side-street, I used to walk to school each day glancing occasionally at the splotches on the houses I was passing where plaster had cracked and broken, and fallen—revealing bullet holes and pockmarks from shrapnel beneath. Though this was on just some little insignificant street in Hungary’s fourth-largest city, World War II had raged down my street once. My landlady, who was a little girl in the 1940s and had grown up on this street, recounted tales of both the German and Soviet soldiers. Why would anyone want to repeat those experiences?

I am cognizant that in releasing this supplement during the Ukraine War, it may quickly become dated, so my goal here is to provide some background on the events and address many of the historical questions that are getting kicked around in the media and by some of the war’s participants. There is, of course, a lot of politics swirling furiously around these events, but I will try to avoid most of that, staying focused on what has happened and what events got us here, and essentially to put the news you see each day about this war into a larger, Eastern European context for you.

• So, Ukrainian isn’t just a dialect of Russian? ..........................

• Isn’t Crimea Russian? Hasn’t it always been Russian? 60

• So how did Ukraine end up with Crimea before 1991? ........ 64

• Why doesn’t Ukraine just give Russia some of its territory (like Crimea or the Donbas), in exchange for peace?......................................................................................

• But isn’t Ukraine corrupt?

• Is Ukraine Nazi or fascist, like Putin claims? ..........................

• Are you biased in favor of Ukraine in this war?

• Did NATO expansion cause this war? .....................................

• OK, so even if objectively NATO didn’t pose a threat to Russia, aren’t Russian perceptions still important? .......... 77

• Did NATO promise Gorbachev not to expand into Eastern Europe?...................................................................

• Why did NATO expand into Eastern Europe? .......................

• Has NATO expansion strengthened or weakened security in

• If NATO isn’t a threat to Russia, why does Putin see it that way?

How has the war impacted the rest of Eastern Europe?

Is it possible this war may ignite other conflicts elsewhere in

• What does all this talk of “decolonizing” Eastern European or Slavic Studies mean?

Wherein we’ll try to take the current crisis apart, addressing some commonly asked questions. Some of these answers we’ll delve into in greater detail later in this section, but for now, we’ll just directly address these common questions:

Figure 1.1. A Timeline of Russian-Ukrainian Relations Since 1900

Source: Eastern Europe!, by Tomek Jankowski

A: The short answer is, because Russia once ruled Ukraine before, and Putin feels Russia therefore has an eternal right to rule over Ukraine again. It’s like a British prime minister deciding that Britain can only be great if it rules Ireland again. As explored through Chapters 4–6 in this book, Russia came to rule over eastern Ukraine from 1667 on, and the rest of Ukraine from the 1770s on. When Tsarist Russia collapsed into revolution in 1917 Ukraine almost broke free, but ended up instead being divided in half between the Soviet Union and Poland. After World War II, the Soviet Union regained all of Ukraine, until its collapse in 1991. The slightly longer answer is that Putin and the class of people dependent on him who rule Russia still think of Russia as an empire. They deeply resent the collapse of the USSR, and see that collapse not as the inevitable result of a corrupt and poorly led state disintegrating but instead as Russia’s greatness having been stolen by somebody (or some entity)—the West? Ever since he achieved power in 1999, Putin

has sought to restore that greatness—meaning, rebuild Russia’s empire. Russian nationalists like Putin see Ukraine as Russia’s doorstep, as the first puzzle piece in any Russian empire. Putin believes that if Russia can’t rule Ukraine, it is no longer an empire, and that means (in his Social Darwinian mind) it will end up being ruled by another empire.

Figure 1.2. The Dire Military Situation in Ukraine in mid-March 2022

Source: Institute for the Study of War4

Q: OK, so why invade Ukraine now?

A: This is a good question, and one nobody really knows the answer to (except Putin himself). Why now? Putin claimed in his speech the morning of the invasion that Russia had to stop NATO in Ukraine—either NATO influence in Ukraine, or Ukraine joining NATO?—but there was nothing about to happen on that front in 2022. The idea of Ukraine joining NATO

4 “Time-lapse of Assessed Control of Terrain in Ukraine, February 23rd, 2022, to September 30th, 2023.” Institute for the Study of War (2023 Institute for the Study of War and AEI’s Critical Threats Project made possible by the Dr. Jack London Geospatial Fund at ISW). Retrieved from: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/733fe90805894bfc8562d90b106aa895

Europe: The Ukraine War Edition

was floated in 2008, but it was controversial then in the West, and still was in 2022. Many in the West were wary of Ukraine joining the alliance for a variety of reasons (e.g., corruption in Ukraine, institutional weakness in Ukraine, political instability, a weak army, after 2014 Ukraine’s proxy war with Russia over Crimea and the eastern Donbas region), so there was nothing at all imminent or inevitable about Ukraine joining or becoming closer to NATO in 2022. Even as late as the summer of 2023, more than a year after Russia invaded and Ukraine had proven the progress it had made in terms of political and military reforms, the alliance still only held out vague promises at its summit in Vilnius that maybe, someday, Ukraine will join.

Figure 1.3. The Military Situation in Ukraine in October 2023

Source: Institute for the Study of War5

In fact, there doesn’t seem to have been anything going on in Ukraine in 2022—e.g., imminent foreign alliances, local or presidential elections, foreign troops being stationed in Ukraine—that might have seemed provocative to Moscow. So why did Putin invade in 2022? I suspect the real reasons all lie in Putin’s head. Ever since the botched 2012 elections in Russia, Putin’s popularity has been slowly sliding. Russia’s living standards and economic situation had also been deteriorating for a bunch

5 “Assessed Control of Terrain in Ukraine as of August 4, 2023, 3:00 PM ET.” Institute for the Study of War (2023 Institute for the Study of War and AEI’s Critical Threats Project made possible by the Dr. Jack London Geospatial Fund at ISW). Retrieved from: https:// storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/36a7f6a6f5a9448496de641cf64bd375

of reasons, perhaps causing some concern for Putin. Another important factor may have been Putin’s own ticking biological clock. Remember that at the time of the invasion he was sixty-nine years old—sixty-nine Russian years old, in a country where the average life expectancy for men is seventy-one. Now, he’s a healthy and fit guy by most measures, but still—if he was going to go down in history as a great national hero who expanded Russia’s borders, then he needed to get a move on. Given how easily Russia seized Crimea in 2014, he probably thought in 2022 that taking Ukraine would be a similarly routine smash-and-grab that would revive his ratings at home. In other words, despite Putin’s claims that he was forced to act, in reality he probably just saw opportunity and thought he could get away with invading Ukraine now.

Q: Why has the Russian army performed so badly in this war?

A: How? Nobody expected the Ukrainian Army to last long when Russian forces invaded in February 2022. The truth is that I didn’t. I thought there would be some heroic resistance here and there, but the end result would look like what happened in Czechoslovakia in 1968. I am so happy that I was wrong. But what didn’t I and others across the world see?

• Military reforms: Mark Galeotti6 goes into some detail on the military reforms, but as he observes —for all the rubles spent so far, it hasn’t been nearly enough. The Russian Army still suffers from some Soviet-era operational and organizational maladies. I can confirm this through anecdotes by Western journalists and military analysts as this war unfolded, which described Russian military problems that sounded straight out of the 1970s and 80s Viktor Suvorov books.7 Corruption, poor (or uneven) training and equipment maintenance continued to bedevil Russian forces, for instance.

• Putin: A key ingredient in the Russian army’s failure has been Putin himself. Putin was a mid-level KGB agent with minimal military experience—certainly no combat or unit leadership experience. Western analysts watching the opening stages of Russia’s invasion were astonished because the Russian army wasn’t following its own doctrine or SOPs (standard operating procedures). It appears that Putin and his political cronies did all the planning, without involving or referencing the Defense Ministry or army leadership—you know,

6 Galeotti, 2022

7 Suvorov was a pseudonym for Soviet defector Vladimir Rezun who, after his debriefing by Western intelligence agencies, wrote a series of books on the Soviet Army for Western audiences.

the professionals. Galeotti reports that most Russian generals were not informed that the invasion was happening until a day or so before it launched.8 There were almost no supplies or reinforcements prepared, because Putin apparently believed Ukraine would be a cakewalk. This led to bizarre circumstances like Russian tanks being forced to enter cities unsupported, leaving them sitting ducks—again, against standard Russian military practices.9 Clearly, there were no contingency plans. Most Russian soldiers had to fight through the first winter of the war without adequate winter gear, for instance. Putin has proven he is no military genius. Putin’s incompetence and miscalculations have really gutted the Russian military. A joke making the rounds in Ukraine after the Prigozhin Uprising (July 2023) in Russia went like this: “In 2021, the Russian Army was the second strongest in the world. In 2022, it was downgraded to the secondstrongest army in Ukraine. In 2023, it is now the second-strongest army in Russia.”

Days into Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, global satellites spotted a convoy of tanks 10 miles (16 km) long headed for Kyiv. Clearly, the Ukrainian capital was doomed. But instead of those tanks crushing Ukrainian resistance, their convoy stalled, and actually grew over the next several days to be 35 miles (56 km) long by February 28. What were the Russians planning?

As it turned out, this wasn’t a convoy but a massive traffic jam. It consisted of tanks, armored vehicles, troop carriers, and supply trucks. And it was stuck, going nowhere. Some of its problems came from the Ukrainians who had destroyed bridges in this convoy’s path and harassed it along its way. Another issue was that winter had turned the countryside into a morass of mud, forcing most of the Russian military vehicles to keep to paved roads. But the larger issue was simply that Russia’s military was not prepared for any of this. It had expected to simply drive from the Russian border to Kyiv unmolested. When it did encounter delays, the Ukrainians

8 Galeotti, 2022: p. 347

9 A tank wandering down an urban street in 1944 unsupported by infantry was essentially committing suicide, and this was still true in 2022, but that is the position Putin put the Russian Army in.

quickly overwhelmed Russian forces and, worse, more vehicles from Russia continued to join it and became trapped in it. They had brought almost no gas or food, and no maps. Engines idling for days overheated and, with no spare parts, quickly became useless. These vehicles were declared dead and pushed off the road, out of the way. Heavy military vehicles also need special tires, and these tires need to be rotated regularly—which they were not, leading to large numbers of trucks blowing their tires and being pushed off roads on their rims. The final piece of the puzzle was very poorly planned communications, so that different units in the traffic jam could not communicate with one another, or with their bases back in Russia. The world kept watching for weeks expecting the “convoy” to lurch forward and take Kyiv but that never happened. Instead, those few Russian forces that did reach Kyiv were unsupported and were eventually defeated, while Ukrainian forces took the opportunity to attack exposed units throughout the traffic jam. Ukrainians also recovered both valuable supplies and critical intelligence from abandoned vehicles. Finally, four weeks after the invasion had begun, the Russian army was able to get enough gas and supplies to bring vehicles back to Russia.

• Peace: Putin’s belief that Ukraine would fall easily led him to commit a Russian army in 2022 that was in peacetime mode, meaning it only had a limited number of personnel and equipment, and many of those personnel were “weekend warriors.” Had the Russian Army been given time to fully prepare and mobilize to a wartime footing, and if Putin had left the planning to people who actually knew what they were doing, things would likely have turned out differently in 2022. After more than six months of excruciating defeats, Putin finally launched a “partial mobilization” in September 2022, but by that point the Russian Army had lost the initiative. In any event, Putin squandered the estimated 300,000 newly mobilized troops by deploying many of them immediately to the front with almost no training and some without adequate equipment. The world expected a major Russian offensive to materialize in early 2023 using these new recruits, but it never happened. Instead, these recruits mostly died in pointless World War I–style frontal assaults as cannon fodder, achieving little. British intelligence inferred in late 2023, and a Russian general confirmed, that Russian front-line troops are not being rotated, meaning those fighting on the front line are not getting any respite or recovery time—this also means they are not receiving any

additional training.10 Meanwhile, rumors have continued to circulate since that at some point Putin will launch another round of total or partial mobilization.

• Morale: A final part of the story is, I think, morale. For all its foibles, the Red Army of World War II days proved (eventually) to be a very effective military force. Yes, it relied on a lot of Western supplies, but Soviet soldiers fought ferociously. An important distinction is that those Soviet soldiers of the 1940s saw themselves as defending their homes and homeland. They were motivated by an invasion of their homeland that killed millions of their fellow citizens and laid waste to their cities and villages. In contrast, for all Putin’s claims of a NATO threat, it seems average Russian soldiers don’t buy it. They see the war more as the poorly conceived foreign adventure it is, rather than the desperate defense of the Fatherland Putin claims. Despite all the polls asserting widespread Russian enthusiasm for Putin’s war, Russian soldiers’ poor morale seems to betray a more realistic understanding of this war, and they know their families back home are in no real danger—at least not from Ukrainians or NATO. Simply said, I think Russian soldiers would be behaving very differently if they really thought they were defending Russia.

• Lessons unlearned: One of the most bizarre aspects of Russia’s behavior in this war has been an inability to learn from mistakes and change behaviors. To be fair, the Russian Army has made some important adaptations, particularly in the spring and summer of 2023, that have successfully slowed Ukraine’s counter-offensive. Still, even seasoned Western military analysts who have followed Russia’s military development for years have been astonished by its institutional rigidity and inability to pivot. Some of this is Putin’s fault, simply because politically, he cannot admit defeat and so a pointless war grinds on, costing lives, equipment, and money for no reason other than an incompetent leader’s ego. But the Russian military is suffering long-term damage in Ukraine that will likely take decades to repair, seriously compromising Russia’s real security in the process. Putin deserves primary blame for that, but Russia’s political and military establishments have shown a remarkable lack of imagination, initiative, or leadership throughout this war. Change, any change, really seems to be Russia’s enemy.

• A Chinese viewpoint: Former Chinese ambassador to Ukraine Gau Yusheng put together some observations about the war for the

10 Maria Kholina. (2023 September 21). “British intelligence explains Russians’ low morale and inability to advance.” RBC-Ukraine. Retrieved from: https://newsukraine.rbc.ua/ news/british-intelligence-explains-russians-low-1695281362.html

Chinese foreign service shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine, and he listed five core reasons for Russia’s poor military performance:11

{ “First, after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, Russia has always been in a historical process of continuous decline; this decline is first and foremost a continuation of the Soviet Union’s decline before its disintegration and is also related to the mistakes of the Russian ruling clique in domestic and foreign policies. Western sanctions have further intensified this process. The so-called revival or revitalization of Russia under the leadership of Putin is a false proposition that simply does not exist; the decline of Russia manifests in its economy, military, science and technology, politics, society, and all other fields, and has also had a serious negative impact on the Russian military and its combat strength.”

{ “Second, the failure of the Russian blitzkrieg and the failure to take quick action indicates that Russia is beginning to fail. Its economic and financial resources, which are a far cry from its status as a so-called military superpower, make it very difficult to support a high-tech war that costs hundreds of millions of US dollars a day. The embarrassment of the Russian army’s defeat due to poverty can be seen everywhere on the battlefield. Every day the war drags on is a heavy burden on Russia.”

{ “Third, Russia’s advantages over Ukraine in terms of military and economic strength have been offset by Ukraine’s resolute and tenacious resistance and the huge, continuous, and effective assistance of Western countries to Ukraine. The generation gap in weapons technology and equipment, military understanding, and combat models between Russia and America and other NATO nations has further highlighted both sides’ strengths and weaknesses.”

{ “Fourth, modern wars are necessarily hybrid wars, covering the military, economics, politics, diplomacy, public opinion, propaganda, intelligence, information, and other fields. Russia is not only in a passive position on the battlefield but has also already lost in other fields. And this has determined that it is only a matter of time before Russia is finally defeated.”

{ “Fifth, when and how this war will end is not for Russia to decide. Russia’s hopes to end the war as soon as possible, while ensuring it achieves vested its vested interests, have been dashed. In this sense, Russia has lost its strategic dominance and initiative.”

11 “Gao Yusheng, Former Chinese Ambassador to Ukraine: The Trend of the RussianUkrainian War and Its Impact on the International Order” (based on a machine-dependent translation into English). (2022 May 10). China Law Translate. Retrieved from: https:// www.chinalawtranslate.com/en/gao-yusheng-russia-war-comments/

Q: How did Ukrainians manage to achieve so much in this war?

A: In stark contrast to the Russian military, Ukraine and its armed forces have shown astonishing resiliency and adaptability. Western military experts have also taken important lessons from the Ukrainian experience, including in how Ukrainian soldiers have used Western technology.

• Past performance is not indicative of future results: One reason nobody expected Ukrainian forces to do well in 2022 is that when Russia seized the Donbas region and Crimea in 2014, Ukrainian military forces were in an awful state. Some 70% of the Ukrainian Army’s forces in Crimea defected to the Russian side.12 Before that war, Ukraine’s pro-Russia president, Viktor Yanukovych, had gutted the Ukrainian Army through a series of budgetary cuts so that on the morning the Crimea crisis began, the army’s total troop strength was only 41,000—and of that, only about 6,000 were really combat-ready.13 Few of those soldiers had much experience with their weapons, and most of those weapons were at least 20 years old.14 Institutional corruption also crippled military efforts. By mid-2016 Ukraine did manage to mobilize some 200,000 active-service military personnel.15 But Ukrainian soldiers paid dearly for the army’s poor organization, equipment and training: by 2017, the Ukrainian army had lost “… a combined total of 10,710, including 2,333 killed and 8,377 injured”16 in the fighting in the country’s east against both Donbas separatists and the Russian Army. Despite some improvements over the next couple years, Ukrainian soldiers continued to complain loudly about uneven training, supplies, and unclear strategy.

• Change time: But something did change—dramatically. Almost immediately the government that replaced Yanukovych when he fled began a series of big military reforms, profoundly transforming its command and control, training, education, organization,

12 Valeriy Akimenko. (2018 February 22). “Ukraine’s Toughest Fight: The Challenge of Military Reform.” The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved from: https://carnegieendowment.org/2018/02/22/ukraine-s-toughest-fight-challenge-ofmilitary-reform-pub-75609

13 Louis-Alexandre Berg and Andrew Radin. (2022 March 29). “The Ukrainian Military Has Defied Expectations. Here Is How U.S. Security Aid Contributed” (Blog post). The Rand Corporation. Retrieved from: https://www.rand.org/blog/2022/03/the-ukrainianmilitary-has-defied-expectations-here.html

14 Akimenko, 2018

15 Ibid

16 Ibid

procurement services, logistics systems, and infrastructure.17 A key goal was not just NATO-standard compliance by 2020, but to achieve full NATO-level “interoperability,” meaning the ability to work directly with NATO forces. The Ukrainian Army has also had to deal with constant change—weapons from all over the world (each requiring their own detailed training), and advice, intelligence, and training from militaries all over the world—forcing the Ukrainian military to become very adaptive.

• Help? NATO (especially Turkey) did play a role in helping Ukraine reform its military capabilities through funding, training, and strategic advising. However, what was significant about the NATO aid was that it didn’t focus on the biggest, newest, shiny weapon systems but instead helped Ukraine with a very bottom-up operational redesign that helped the country create a flexible, decentralized structure (spanning formal army and civilian defense forces), which gave local military authorities flexibility in how they achieved their goals. NATO aid focused on functionality, rather than new toys. Readers of the 1970s and 80s books by Viktor Suvorov will recognize that the Soviet Army struggled with this middle-tier of military management (what the U.S. Army calls non-commissioned officers, or NCOs). The armies of the former Soviet states after 1991, children of the Soviet Union, all inherited this weakness. The Ukrainian Army was able, by 2022, to overcome that deficiency and though outnumbered in both men and weapons, was able to run operational circles around the rigid, baffled Russian Army.

• Reform at the top: When elected president in 2019, Volodymyr Zelensky launched major military reforms making enough headway by 2021 that the West felt comfortable to start selling Ukraine more modern weapons.18

• Bottom-up: Another part of the story is more organic, however. When the Ukrainian Army was first struggling in 2014, an estimated 15,00040,000 civilian volunteers rushed to the aid of Ukrainian forces in makeshift paramilitary groups (like the infamous Azov Battalion).19 Over the next few years the Ukrainian Army was able to gain control over many of these groups and formalize their equipment, training, and command, essentially absorbing them into the army. But in 2014, they provided instant (if inexperienced) manpower the army

17 Arda Mevlutoglu. (2022 April 7). “Ukraine’s Military Transformation between 2014 and 2022.” Politics Today. Retrieved from: https://politicstoday.org/ukraine-militarytransformation/

18 Berg and Radin, 2022

19 Akimenko, 2018

desperately needed. The impact of these volunteers convinced Kyiv to create in January 2022—just in the nick of time—the Territorial Defense Force, a civilian-extension of the military with 10,000 career positions in peacetime but designed to train and equip 120,000 reservists.20 Though barely two months old when Russia invaded in February 2022, this defense force proved crucial in the opening battles not just in mobilizing average civilians but also by having command, intelligence, and distribution networks already functioning in place, on the ground, enabling local citizens all over Ukraine to immediately contribute to the war effort. (CNN reporter Matthew Chance, who was in Kyiv the night the invasion began, reported encountering armed civilians on a street that first night with crates of Molotov Cocktails —homemade gasoline bombs—and when he asked where they’d acquired them, they replied that old women in nearby apartment blocks were busily making them.)21 The famous scenes we all saw of Ukrainian farmers towing Russian tanks behind their tractors were not an accident, but an organized effort.

• Democracy in action: Another key aspect that caught everyone by surprise was the degree to which Ukraine united behind the war effort. Ukraine held together not just militarily but administratively. Democratic institutions both at the center in Kyiv and throughout the country at the county, city, and village levels all continued to function and cooperate. This spanned the ethnic and language divide, so that (to the astonishment of many) even Russian-majority regions such as Odesa,22 Kherson, and Kharkiv saw huge local civilian participation in defense efforts. Simply, Ukraine kept working as a country. Over the late summer and autumn of 2022, after the Russian army retreated in the face of successful Ukrainian counter-offensives, in frustration Putin launched multiple salvoes of rocket and missiles at Ukraine’s utilities and infrastructure—but such is the level of coordination and cooperation that utilities have mostly continued functioning. Even during the worst months of the invasion, under CEO Oleksandr Kamyshin, Ukraine’s state railway system kept ferrying people and

20 Liam Collins. (2022 March 8). “In 2014, the ’decrepit’ Ukrainian army hit the refresh button. Eight years later, it’s paying off” (Blog post). The Conversation. Retrieved from: https://theconversation.com/in-2014-the-decrepit-ukrainian-army-hit-the-refreshbutton-eight-years-later-its-paying-off-177881

21 CNN. (2022 December 28). “CNN reporter reveals surprising moment he came face-toface with Russians on battlefield.” YouTube. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=F2vIC7Usuik

22 In Russian, Одесса (Odessa), in Ukrainian, Одеса (Odesa)—and we’ll use the Ukrainian version since it is legally a Ukrainian city today.

supplies all over the country, and kept Ukraine connected to key allies Poland and Romania. Probably more than any other element of Ukraine’s resistance, this organizational resiliency has truly stumped Russia.23

{ This element shouldn’t be too romanticized; a minority of (ethnic Russian) Ukrainian citizens are pro-Russian, and Ukrainian forces have had to be wary of civilians in areas of their control sometimes providing intelligence to Russian forces. It’s a reality. There has also been an ugly, unwritten covert war raging in both Russian-occupied and liberated areas by special forces units targeting collaborators on both sides. Still, the overwhelming loyalty and support Russian-majority regions have demonstrated for Ukraine has stunned everyone.

• Invasion: Another key element is that Ukraine was invaded, and nobody likes to be invaded. The Russians behaved like conquerors the moment they crossed into Ukraine, inspiring resistance even in majority ethnic Russian regions. Putin then compounded this error of arrogance as the war progressed by behaving like Hitler during the Blitz against Britain in 1940, where Hitler tried to break British fighting resolve by targeting British cities. Similarly, in frustration Putin used his dwindling long-range attack capabilities over 2022–23 to attack civilian targets across Ukraine, pointlessly killing civilians and inflicting suffering on them—and hardening Ukrainian resolve.

• Lights, Camera, Message: Zelensky is an actor and a veteran of a few Ukrainian TV shows—meaning, he understands the power of TV and image. He and his team have done a phenomenal job of portraying Ukraine’s victories and its suffering to the world, completely derailing the Kremlin’s narrative. Despite Putin’s best efforts to portray Russia as the victim in this war, a daily flood of videos, pictures, blogs, and interviews from average Ukrainian soldiers and civilians has just overwhelmed and drowned out the Russian self-pity story. To a degree that astonishes veteran Kremlinwatchers, Putin’s once invincible Russian propaganda machine seems almost…impotent. In March 2023 Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov began a speech in front of an international crowd in India by describing the invasion as a war “…launched against us,” and the crowd immediately burst into loud laughter. Lavrov’s stunned expression spoke volumes.

23 And again, compare and contrast this with the paralysis of security forces in Russia during the Wagner Uprising in July 2023.

Q: How can Putin still think Russia can win after all its humiliating defeats in this war so far?

A: Putin is likely looking at a couple examples from recent Russian history for hope. In the Winter War of 1939–40, Stalin attacked tiny little Finland, but Soviet forces were trounced by the Finns through superior training, better use of the local topography, better organization, and in some cases (given the extreme winter conditions), better equipment. But the Red Army was huge, and was able to absorb the massive losses the Finns inflicted on it until it finally just overwhelmed them in the spring of 1940.

Something similar happened in World War II (outlined in Chapter 7 of this book), where the unprepared Soviet forces suffered massive losses in men and equipment in 1941 that quickly translated into Nazi forces advancing more than 700 miles (1260 km) by November to just outside Moscow. But Moscow miraculously held, and the German strategy the following year in 1942 that shifted southward led to the Nazi disaster at Stalingrad.

In both cases Russia sustained huge losses initially and seemed on the brink of total defeat, only to eventually rebound and overwhelm the enemy with its sheer numerical advantage. Putin may see these two examples as reflective of a Russian way of war, and that somehow, Russia will bounce back and vanquish its enemies. This flummoxed Ukrainian general Valery Zaluzhny, according to the Economist:

It has also undercut General Zaluzhny’s assumption that he could stop Russia by bleeding its troops. “That was my mistake[,” said Zaluzhny.] “Russia has lost at least 150,000 dead. In any other country such casualties would have stopped the war.” But not in Russia, where life is cheap and where Mr. Putin’s reference points are the first and second world wars, in which Russia lost tens of millions.24

Or…? Or he may want instead to study the examples of Russia at war in 1856, or in World War I where the losses just kept piling up, and there was no rebound, no final recovery that snatched victory from the jaws of defeat. In both the Crimean War and World War I, poor performance, poor treatment of average Russian soldiers, and deteriorating living standards for average Russians all contributed to eventual Russian defeat—and in 1917, even worse than defeat.

24 “War of attrition; Ukraine’s commander-in-chief on the breakthrough he needs to beat Russia.” (2023 November 1). Economist, pp. 43–44. Retrieved from: https://www.economist .com/europe/2023/11/01/ukraines-commander-in-chief-on-the-breakthrough-he-needsto-beat-russia

A: As of this writing, things are going slowly—but as Yale historian Timothy Snyder, a specialist in the history of Central and Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, and the Holocaust, reminds us, wars take time and they are grueling, grinding events filled with lots of doubt and pain. When you look back on historical wars, you already know the outcome so the gruesome details seem a little less brutal, but for the people living through those events…

Part of the problem is defining “winning.” So who is winning?

• Ukraine: Simply by still existing despite all-out assaults by its much larger neighbor, Ukraine is a winner. While smaller in size, Ukraine’s armed forces have proven far nimbler and more adaptable to modern combat than Russia’s army. Russia’s few victories in this war have mostly been through being able to overwhelm Ukrainians through sheer number advantages, like Russia’s mass rolling artillery at Mariupol and Bakhmut. But even more importantly, this war has inspired Ukraine to overcome its many internal differences (western versus eastern Ukrainians, ethnic Ukrainians versus ethnic Russians, industrial areas versus farmlands, inland Steppe versus coastal fishing and trade, etc.) to unite as never before in Ukrainian history. As I mention in Chapter 6, when Ukraine had a shot at independence in 1918, it slid instead into civil war. Again, it astonished everyone that even majority Russian-speaking regions like Odesa, Kharkiv, and Kherson overwhelmingly united against the invaders in 2022. There are legions of Ukrainian memes thanking Putin for uniting Ukraine. Ukraine has also gained new potential business and economic relationships around the world through its new allies, and as many analysts have noted, the technological sophistication of the many modern weapon systems Ukraine has been adopting and using in this war has trained a whole generation of young Ukrainians in the new technologies—boding well for a postwar economy.

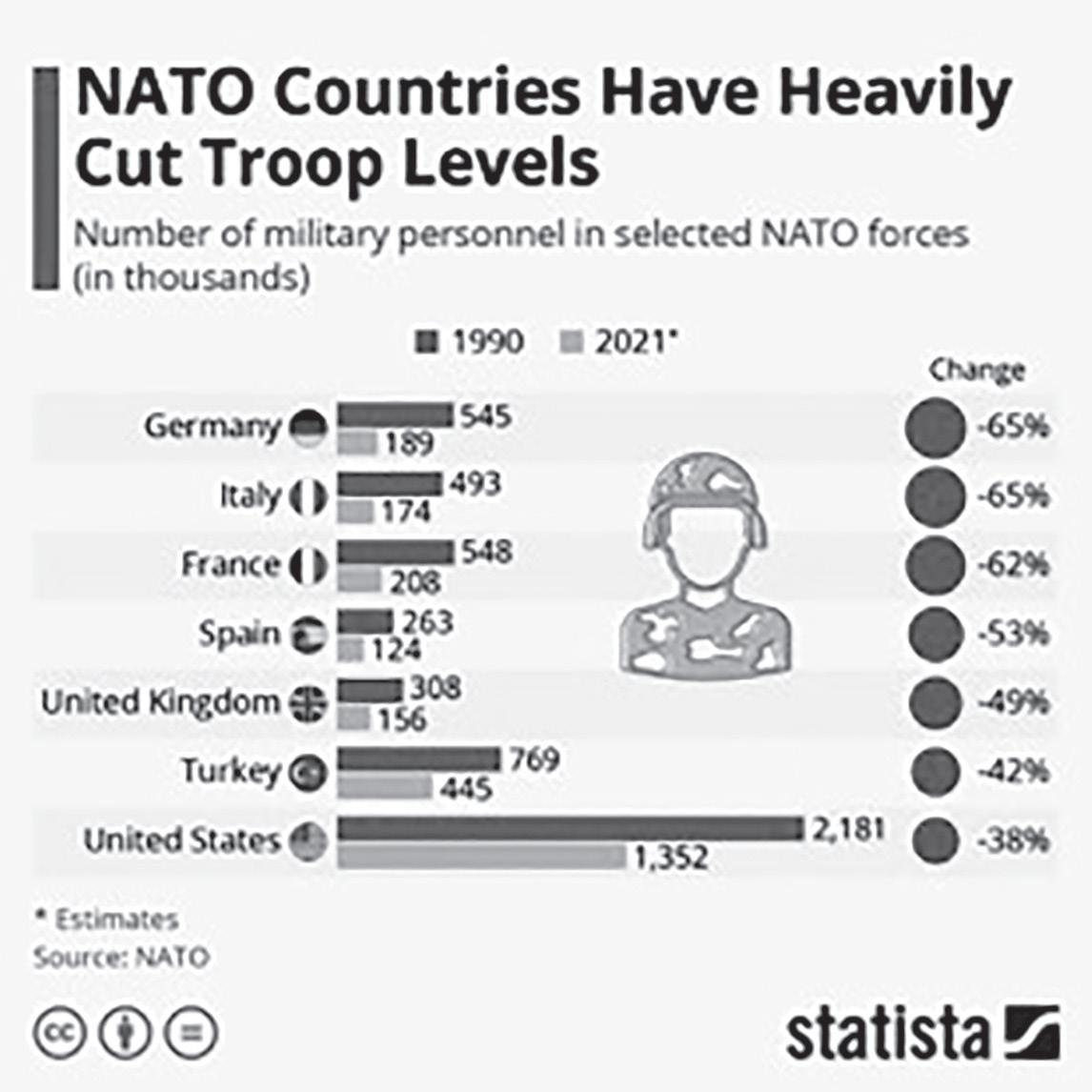

• NATO: NATO’s fortunes were flagging before this war began. Its Cold War purpose seemingly gone, members were slashing budgets and limiting coordination with allies. Many resented being drawn into America’s post–9/11 wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. And then Putin invaded Ukraine, clumsily tripping into a long-drawn-out colonial war on Europe’s fringe, reminding Europeans and others of the importance of a security organization like NATO. NATO has also gained two new strategic members, Finland and Sweden. Both have small militaries, but they are technologically adept and geared toward addressing a Russian threat. NATO has also regained some prestige that was diminishing in the years after the Cold War, as the

Ukraine War has suggested the superiority of both Western tactics and equipment over Russia’s remains real and palpable.

• Eastern Europe: It turns out the Poles and Baltic peoples were right all along, that Putin did pose a serious strategic threat to Europe. Squabbling over issues like Ukrainian grain in the region may scupper gains, but Western Europe has learned that it needs to take Eastern Europe more seriously. Eastern European voices are gaining importance across all European institutions. In some ways, this war has closed the postcommunist loop for the region by bringing back into focus the reality that local economic and democratic development must be linked to security, and any solutions must be pan-European.

• Putin: This may seem counterintuitive, but while Russia is losing this war badly, it has provided Putin with the excuse to further tighten his control over Russia and dispense with any annoying democratic window-dressing. To be sure, some of the shine has come off his dictatorship at home and his incompetence has become apparent, but his grip on power is stronger than ever. This is a problem for Ukraine, because Putin doesn’t dare stop this war; his death-grip on Russia depends on a non-stop crisis—i.e., this war.

• China: Western sanctions have isolated Russia’s economy, making Putin increasingly dependent on Chinese willingness to prop up Russia’s economy and bankroll Putin’s war. Russia’s battlefield defeats have translated into great gains for China across Russia’s economy (especially in all the oil, gas, and mineral-extraction industries) in ways that will be very difficult for future Russian leaders to extricate Russia from. Other countries have stepped into the void left by the West in Russia’s economy as well, particularly India, but none to the degree China has. Chinese banks have suddenly become a major force in Russia’s economy, with a huge and growing portion of Russian debt being denominated in Chinese renminbi.25 Russia is becoming a Chinese protectorate. Per Business Insider:

But the think tank argues that much of the partnership has been more to Beijing’s benefit than it has been to Moscow. Though China is one of Russia’s only reliable

25 Joseph Wilkins. (2023 September 4). “Russia is becoming increasingly dependent on Chinese banks as its yuan borrowings more than quadruple.” Yahoo Finance. Retrieved from: https:// finance.yahoo.com/news/russia-becoming-increasingly-dependent-chinese-175558080 .html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_ referrer_sig=AQAAAEExAr912IYb4EKXcmzY7lHP85NwtA9zCYKLGgnYo_N79jU4ym gTJj9ZWvNKCyL8mQwO4z45pb4djBp8RZWfqeFBlAbnXqAB8Aapzl5eDNafYcd9jCDt 2Wg2wWzUmrI9NPRYT-8SelHQjRlnE-FWbUzzk5OXsx9ktIKtD1CZJ5rL#:~:text=Russia’s%20deepening%20isolation%20from%20the,move%20away%20from%20the%20dollar.

trading partners at the moment, the nation has neglected to make major investments in Russia, Graham noted.

Beijing also appears to be prioritizing its own economic interests, such as by using its relationship with Russia to trim other trade ties on terms “inordinately” favorable to itself, Graham said. He says the nation has also worked to expand its connections elsewhere in Asia, which are actually coming at Russia’s expense.26

• India: While not nearly to the degree China has, India is benefitting tremendously from Russian trade agreements that are suddenly very favorable to India. In some respects the war has put Delhi in a difficult spot as it dances a delicate line between Russia and the West, never wanting to completely side with or abandon either side, but India has gained prestige as an important intermediary and international power-broker.

• The Global South: The Russian invasion of Ukraine has been seen in a couple different lights outside of Europe and the West. Some see a very traditional colonial situation where a stronger power is trying to impose itself on a smaller neighbor through sheer blunt force— and that sure looks very familiar to many people across Asia, Africa, and Latin America. But others instead see the West going nuclear over a war of aggression on its own periphery, while ignoring wars that have been raging for years in places like Yemen, Congo, Sudan, Ethiopia, or Myanmar with barely a peep. Though there is sympathy for the suffering of Ukrainians, some see a double-standard in the West’s reaction to Russia’s aggression. (Worse, some also invoke the Iraq War as an example of alleged Western hypocrisy.) And of course, Putin’s anti-Westernism finds some sympathetic ears in parts of the world. Without wading into these arguments, one thing that is important is that the West’s attempts to isolate Russia economically have strengthened the voices of the Global South’s economies in global affairs. The Global South (generally identified as the lessdeveloped but rising economies of southern Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America) has suddenly found itself being courted by Western, Russian, Chinese, and Ukrainian diplomats. Issues such as Russia’s attacks on Ukraine’s grain trade have also highlighted the symbiotic nature of the world’s economic relationships, reminding many of our global inter-dependence.

26 Jennifer Sor. (2023 October 13). “China’s economic partnership with Russia is so lopsided that Putin needs the help of the US —but he’d never admit that, think tank says.” Business Insider. Retrieved from: https://www.businessinsider.com/russia-economy-news-chinaputin-trade-west-sanctions-ukraine-war-2023-10

• Iran, North Korea: International pariah states Iran and North Korea have also made hay with this war by supplying Russia with basic ammunition, drones, and supplies, in exchange for some international credibility in the form of official visits with Putin.

Q: Will Putin try to invade Moldova, or maybe the Baltics, next?

A: Neither is likely. Pro-Kremlin media personalities and a few Russian officials (including some defense ministry officials) have made threats to the effect that Russia should invade these countries, or even Eastern Europe as a whole—but Ukraine has ground down Russia’s armed forces to an astonishing degree. Numbers are not known precisely, but while Russia still has considerable military resources in sheer numbers, its losses in equipment and trained, experienced soldiers in Ukraine have severely weakened Russia’s offensive military operation capabilities. Now, when a crazy guy has the steering wheel, well, never say never, but any rational assessment of Russia’s military capabilities in 2024 is going to conclude that any further empire dreams are going to have to wait a few years. And as I note through some quotes in Chapter 10 of this Second Edition of this book, NATO membership is probably what has ensured the continued independence of the Baltic states over the past thirty years.

Q: What has been the human toll in this war so far?

A: This is a tough question. Neither side is forthcoming with accurate casualty figures. Obviously, they each highlight and possibly exaggerate the number of killed on their enemy’s side, while minimizing their own losses. Many groups, from news organizations and the UN to government intelligence agencies, have been estimating losses. And of course, they mount daily. More and more people’s lives are shattered or destroyed every single day this war continues.

• Ukraine: In August 2023 the U.S. estimated that some 70,000 Ukrainian troops had been killed and 100,000 to 120,000 wounded since February 2022.27 (That date is important because most Ukrainians consider this war as having started in March 2014, with Putin’s invasion of February 2022 only an escalation of an alreadyexisting war.) The United Nations estimated civilian losses in Ukraine

27 Helene Cooper, Thomas Gibbons-Neff, Eric Schmitt, and Julian E. Barnes. (2023 August 18). “Troop Deaths and Injuries in Ukraine War Near 500,000, U.S. Officials Say.” New York Times. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/18/us/politics/ukrainerussia-war-casualties.html

(as of early September 2023) as being 27,149 total: 9,614 killed and 17,535 injured.28

“Ten thousand civilian deaths is a grim milestone for Ukraine,” said Danielle Bell, head of the monitoring mission. “The Russian Federation’s war against Ukraine, now entering into its twenty-first month, risks evolving into a protracted conflict, with the severe human cost being painful to fathom.”

“Nearly half of civilian casualties in the last three months have occurred far away from the frontlines,” she added. “As a result, no place in Ukraine is completely safe.”29

• Russia: In late 2023, as Russia released its proposed budget for 2024, that budget included a line item allocating compensation funds for the families of 102,700 military personnel killed in Ukraine.30 According to US estimates from August 2023, Russia’s military casualties were then nearing 300,000, including as many as 120,000 deaths and 170,000 to 180,000 injured troops.31

Keep in mind that the brutal Second Chechen War (1999–2009) cost an estimated 4,379 Russian soldiers killed,32 and in the Soviet-Afghan War (1979–89) some 15,000 Soviet troops were casualties (meaning, wounded and killed).33 And both conflicts traumatized Russian society.

28 “Ukraine: civilian casualty update 11 September 2023” (Media Center). (2023 September 11). United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved from: https://www.ohchr.org/en/news/2023/09/ukraine-civilian-casualty-update-11september-2023

29 Aila Slisco. (2023 November 21). “How Russia’s Military Losses Compare to Ukraine’s This Month.” Newsweek. Retrieved from: https://www.newsweek.com/how-russiasmilitary-losses-compare-ukraines-this-month-1845800

30 Isabel van Brugen. (2023 October 13). “Russia’s Likely Death Toll in Ukraine Revealed in Government Filing.” Newsweek. Retrieved from: https://www.newsweek.com/russiadeath-toll-ukraine-war-1834486

31 Helene Cooper, Thomas Gibbons-Neff, Eric Schmitt, and Julian E. Barnes. (2023 August 18). “Troop Deaths and Injuries in Ukraine War Near 500,000, U.S. Officials Say.” New York Times. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/18/us/politics/ukrainerussia-war-casualties.html

32 “Background.” (1997 January 1). Human Rights Watch, “Human Rights Watch World Report 1997—The Russian Federation.” Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from: https:// www.hrw.org/reports/1997/russia2/Russia-01.htm#P110_8966

33 Alyssa Knapp (Curator). (2023). “Soviet-Afghan War (1979–1989)” (“Burning with a Deadly Heat”: NewsHour Coverage of the Hot Wars of the Cold War). American Archive of Public Broadcasting. Retrieved from: https://americanarchive.org/exhibits/newshourcold-war

Journalist Eric Schmitt writes, “According to U.S. assessments [in October 2024], Russian casualties in the war so far number as many as 615,000—115,000 Russians killed and 500,000 wounded. Ukrainian officials have zealously guarded their casualty figures, even from the Americans, but a U.S. official estimated that Ukraine had suffered a bit more than half of Russia’s casualties, or more than 57,500 killed and 250,000 wounded. . . . The official did not specify the number of Russian casualties last month [September 2024] beyond calling it the costliest month for Moscow’s forces. U.S. and British military analysts put Russian casualties at an average of more than 1,200 a day, slightly surpassing the previous highest daily rate of the war that was set in May.”34

All that can be said for certain about fatalities and wounded in this war is that a massive number of people are dying or being wounded at alarming rates unseen in Europe since World War II.

Q: Are we in a new Cold War, or will there be one?

A: Possibly, but likely not. Russia simply doesn’t have the financial or economic resources to sustain a long-term “cold war” in the way the Soviet Union did. Putin’s Russia is far more dependent on China and others for critical resources. There is the very real danger that U.S.-China relations could spin out of control into a Cold War–style confrontation, and Russia would be dragged into that on China’s side, but Russia alone simply doesn’t have the industrial capacity, technology development capabilities, or financial foundations to repeat the 1946–91 experience. China does, but Russia no longer does. Putin certainly can make Russia into a troublesome regional headache for the West and others, and his trump card is always Russia’s Soviet-era nuclear arsenal, but the Soviet collapse and Putin’s kleptocracy have combined to hobble Russia in ways that have severely reduced its impact and voice in the world.

Putin’s own misrule has ensured Russia is no longer capable of the heights of Soviet power and achievement. There is no reason that Russia shouldn’t be a leading economy and power in 2024; the fact that it isn’t more important than it is can be attributed almost exclusively to Putin. If he had followed the Chinese example of an authoritarian state that allowed a relatively free-market economy, Russia would be stronger today and more capable of challenging the West, but he did not. Putin is why Russia cannot compete economically, politically, and technologically on the global stage in any meaningful way, other than rattle its old Soviet nuclear saber.

34 Eric Schmitt. (2024 October 10). “September Was Deadly Month for Russian Troops in Ukraine, U.S. Says.” New York Times. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2024 /10/10/us/politics/russia-casualties-ukraine-war.html

A: Of course, the answer is (as of late 2024), I have no idea. Here are a few of the most likely scenarios, in no particular order:

• Total Ukrainian victory: Ukraine is eventually able to liberate all of its territory from Russian control. This seems less likely as of this writing—but not completely out of the realm of possibility.

• Total Russian victory: Maybe the West tires of supporting Ukraine and Russian forces are able to outlast Ukrainian reserves, and ultimately triumphantly march into Kyiv. I think this is an unlikely scenario, though Putin seems to believe it is a possibility. Even if the West does stop supporting Ukraine in tangible ways, the Ukrainians have inflicted so much damage on Russian military forces that, although Putin keeps trying, Russia doesn’t seem to be capable of effective large-scale offensive operations now. Russia’s offensives in the east and north over 2024 were the largest since 2022, and yet achieved only limited territorial gains against a Ukrainian military starved of resources.

• Negotiations: Maybe both sides would come together (perhaps secretly) and hammer out a cease-fire, or a Korean War–style armistice, freezing the front line wherever it is now. There are many around the world who want this solution. The problem is that it would reward Russia at least partially for its aggression. But even worse, Putin would only view any cease-fire as a temporary halt to combat operations; he would use the respite to rebuild, resupply, and retrain, and then wait for an ideal moment to relaunch the war. The world would be back to square one.

• Stalemate: This is about where things are now, a World War I–style stalemate like the autumn and early winter of 1914, where the Allied (French, British, Belgian) armies had halted the German advance into France, but were too weak to push the Germans out, leading to three more years of stalemate all along the Western Front. Both sides built massive defense fortifications all along the front line, so that when each side launched an attempt to break through the enemy’s defenses the end result was massive, pitched battles (e.g., Ypres, Verdun, the Somme, etc.) that only moved the front line a few hundred yards, with tens of thousands of men dying in each battle—essentially, for nothing. Ukrainians have successfully halted the initial Russian advances and even taken back a lot of territory, but now face entrenched Russian forces that, while under-trained, under-equipped, and poorly led, still often outnumber Ukrainian forces trying to liberate more land. Over the summer of 2023 reports kept streaming in of excruciatingly slow

progress on the Ukrainian forces’ part, definitely moving forward but at a glacial pace as Russian defenses have proven difficult. (Mounting an effective defense in war usually requires fewer resources than attacking.)

{ The Ukrainians made gains. In autumn 2023, the Ukrainians honed the ability to launch missiles to harass Russian ships in the Black Sea, to the extent that Russia has withdrawn its famed Black Sea Fleet to Russian ports for safety. The Ukrainians have also been successfully bringing the war to Russian-occupied Crimea, destroying the Black Sea Fleet headquarters in September 2023.

{ Then again, Russian counteroffensives around Avdiivka and near Pokrovsk in the Donetsk region in 2023 and 2024 have produced some limited gains, though at great cost.

{ Some analysts believe Putin is hoping for the stalemate option, hoping that, short of a decisive victory (which he obviously can’t achieve at this stage), he can instead “freeze” the Ukrainian conflict. This would mean essentially ceasing large-scale military operations, only continuing small, local efforts to keep the war going on slow boil. This is what happened to the war in the Donbas region after an initial flare-up in 2014. By freezing the war, Putin can keep it going for years, possibly decades, using it to destabilize Ukraine while also ensuring Ukraine can never join NATO, since NATO would never allow a member to join that has a current border war raging.

With the outbreak of the latest round of Hamas-Israeli violence, Putin has an opportunity to freeze the Ukraine conflict as it falls out of global news headlines. As noted in Chapter 8 in this book, something similar happened with Hungary in 1956 when the Suez Crisis grabbed the world’s attention, giving Moscow more freedom of action to crush the rebel Nagy government as the West was distracted by the Middle East.

• Russian state collapse or coup: Many observers feel that this war will only end when real political change happens in Moscow. So long as Putin or anyone like him is in power in the Kremlin, Russia will continue to try to conquer Ukraine. Unfortunately, this option seems fairly remote and unlikely.

• Third party: Another less likely scenario would have a third (or fourth) party join the war—probably the most obvious candidate would be NATO, but others such as Turkey (by itself), Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, or China are also possibilities. At this stage it seems very unlikely, but it would seriously upset the status quo and possibly tip the balance one way or the other.

Where are the goal posts? But there’s a problem with all this speculation. The assumption is that this war stops when the shooting stops, but even if Ukraine manages to liberate every square inch (or cm) of its territory, the core problems that created this war—Putin and Russian nationalism—still exist. Ukraine’s problem is that its bigger neighbor has convinced itself that it must control Ukraine, and more than that, that any independent Ukrainian identity (e.g., culture, language, history, etc.) is a mortal threat. One solution would be for Ukrainian forces to liberate Russia, to march all the way to Moscow and overthrow Putin—but obviously, this is not realistic.

So long as Putin and those who agree with him rule Russia, Russia will always be a threat to Ukraine. Russia is going to be a geopolitical problem for Ukraine, for Europe, for the West, and for the world for a long time, and any solution to this war will have to take that into account.

Q: Is Russia really an empire?

A: This gets messy. Legally speaking, no. Russia’s official name is the Russian Federation (Российская Федерация), and at least on paper it is a republic with elected officials, and power distributed across the country’s huge geography (e.g., its oblasts or provinces). On paper, at least, Russia looks like a normal European country.

However, in reality, power is very heavily concentrated in Moscow, to a degree that is difficult for other European countries to fathom. Briefly in the 1990s, under Yeltsin, there was a weakening of the center in Russia and a genuine devolution of some powers to the regions and provinces from Moscow, but this devolution was very limited and easy to reverse (as Putin did in his first years in power after 2000). A federation is a voluntary union of different regions or states, but the Russian Federation was always a Moscow-centered state, created in Moscow for Moscow’s benefit. It tells you a lot about Russian state inefficiency when you realize that political decisions down to the most minute level on the Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia’s Pacific Far East must still be made in Moscow, eight time zones away. The only real autonomy local regions across Russia have from Moscow is mostly achieved through remoteness and inaccessibility: poor roads and communications can be a blessing.

So again: Is Russia an empire? Dictionary time: The Cambridge Dictionary defines an empire as, “a group of countries ruled by a single person, government, or country.” But there is, I think, more to the definition: how empires become empires. The “ruled by” bit is usually involuntary; India didn’t ask to be ruled by Queen Victoria, nor did Constantinople beg Sultan Mehmed II to please rule over it. Empires don’t ask, they take. They conquer foreign peoples and countries. So, again—is today’s Russia an empire? It is a massive state (the largest country in the world, by territory) where a Russian-majority region (European Russia) dominates vast expanses of mostly non-Russian peoples, with a few imperial cities (usually with ethnic Russian majorities but surrounded by non-Russians, like Vladivostok) scattered among them.35 As put by Polish ethno-linguist Tomasz Kamusella:

The “golden standard” of Russian literature encased in imperial-like and elitist Russian of the tsarist and Soviet

35 “Vladivostok” in the Far East means “Conqueror of the East,” while “Vladikavkaz,” north of Georgia, means “Conqueror of the Caucasus.”

periods continues to this day, despite a fifth of the Russian Federation’s inhabitants being ethnically non-Russian. What is more, they inhabit the Asian and Caucasian fourfifths of the country’s territory. So, in spatial terms today’s Russia is overwhelmingly non-Russian. These nonRussian four-fifths denote present-day Russia’s colonies, while the metropolis is limited to the European one-fifth, less the Caucasus. Obviously, some imperial cities with ethnically Russian (or rather creole) pluralities or even majorities dot and effectively control these colonies.36

Perhaps more importantly, Putin and many Russians think of Russia as an empire, both in how it is organized and how it behaves. Empires meddle in other countries’ affairs. Just months after declaring its own independence from the Soviet Union, Russia began inserting its army into conflicts around the former Soviet Union, and each time it did so Russian forces stayed, permanently: Moldova (Transnistria), Armenia and Azerbaijan (the Nagorno-Karabakh war), Belarus, Central Asia (Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, etc.), Georgia in 2008, and the seizure of Crimea and eastern Ukraine in 2014.

In the Yeltsin days, an expression came into use in Russian politics, ближнее зарубежье (“the near-abroad”). As explored in Chapters 9 and 10 in this book, this term refers to now-independent countries once ruled directly or indirectly by the Soviet Union. A further underlying meaning is that once ruled by Moscow, always ruled by Moscow; Putin and Russian nationalists believe modern Russia still deserves to rule these countries —or at least have special and exclusive political rights in them. Former Cold War intelligence officer Douglas Boyd describes:

Flushed with their ill-gotten personal prosperity after seventy years of scant private wealth in Russia, its leaders believe that the near-abroad, in which 25 million ethnic Russians still live, is theirs by right and deeply resent Western intrusion into it by granting membership of the European Union and NATO to these countries. There is even a body of opinion in Western corridors of power that these countries should be written off, in order not to incite the bear to show its teeth.37

36 Tomasz Kamusella. (2023 July). “Going Native: Russian Studies in the West.” Academia. Retrieved from: https://www.academia.edu/104592365/Going_Native_Russian_Studies_ in_the_West?email_work_card=title

37 Boyd, Douglas. The Kremlin Conspiracy: 1,000 Years of Russian Expansionism. Stroud, UK: History Press, 2014; p. 337.

Ukrainian human rights lawyer Oleksandra Matviichuk is pretty clear about all this:

Russia is a modern-day empire. The imprisoned peoples of Belarus, Chechnya, Dagestan, Tatarstan, Yakutiia, and others endure forced russification, the expropriation of natural resources, and prohibitions on their own language and culture. They are forced to give up their identity. Empire has a center, but it has no borders. Empire always seeks to expand. If Russia is not stopped in Ukraine, it will go further.38

Putin’s chief ideologist, Vladislav Surkov, agrees. In an op-ed in official state media that he wrote just before the war, he introduced the term “social entropy” (Социальная энтропия), which (according to Surkov) happens naturally in countries: their societies inevitably disintegrate and decay, and chaos ensues. Successful empires (like Russia) use this to their advantage:

Exporting chaos is not new. “Divide and conquer” is an ancient recipe. Division is synonymous with chaos. Rally your own + divide strangers = you will rule both. Relieving internal tension […] through external expansion. The Romans did this. All empires do this. For centuries, the Russian state, with its harsh and inactive political interior, was preserved solely thanks to the tireless striving beyond its own borders. It has long forgotten how, and most likely never knew how to survive in other ways. For Russia, constant expansion is not just one of the ideas, but the true existential of our historical existence. […] Complaints from Brussels and Washington about Moscow’s interference [in Crimea] and the impossibility of resolving significant conflicts around the globe without Russian participation show that our state has not lost its imperial instincts. […] In the meantime, the world is enjoying its multipolarity, the parade of post-Soviet nationalisms and sovereignties. But in the next historical cycle, globalization and internationalization, forgotten today, will return and cover this twilight Multipolarity.

38 Oleksandra Matviichuk. (2023 May 9). “A Speech to Europe 2023.” IWM. Retrieved from: https://www.iwm.at/news/a-speech-to-europe-2023-read-the-full-text-or-watch-therecording

And Russia will receive its share in the new global gathering of lands (or rather, spaces), confirming its status as one of the few globalizers, as happened in the era of the Third Rome39 or the Third International. Russia will expand not because it is good, and not because it is bad, but because it is physics.40

In Putin’s mind, only a handful of countries in the world deserve real sovereignty and security. Russia is one of them. Other countries— e.g., Poland, Ukraine, Sweden, Kazakhstan, and the Philippines—are only playthings for the Great Powers as far as Putin is concerned, and their rights or interests are subordinate to the world’s dominant empires. As Surkov’s final sentence above illustrates, to Putin, a global Russian imperial victory is both predestined and inevitable.41

Zeitgeist: But “empire” is actually the problem. What Putin doesn’t understand is that most of Europe underwent a profound change after the horrors of two world wars. Despite the triumphalism of the Allies, there was a sense among both winners and losers in 1945 that the World Wars had really been a form of suicide—that the wealthiest and most advanced civilization on the planet had used all its advantages to destroy itself, rather than further humankind. Europeans fell out of love with empires, and instead began to focus on their quality of life. To be sure, this process was slow and fraught with missteps such as India in 1947, Algeria in 1956, or Angola in 1961. But today most Europeans look with shame, or at least reflectiveness, on their imperial pasts. Europe has changed, with much of Eastern Europe also starting down this same path after 1988. Young Poles and French people today do not fear German militarism, for instance. Historian James J. Sheehan describes this post–World War II transformation:

This system provided the incubator within which the states of western Europe were gradually transformed. They became civilian states, states that retained the capacity to make war with one another but lost all interest in doing so. The result was an eclipse of violence in both

39 “The Third Rome” = Tsarist times, the “Third International” = Soviet times.

40 Владислав Сурков (Vladislav Surkov). (2021 November 20). << Куда делся хаос? Распаковка стабильности>> (“Where did the Chaos Go? Unpacking Stabilization”). Актуальные комментарии (Current Commentary). Retrieved from: https://actualcomment.ru/kudadelsya-khaos-raspakovka-stabilnosti-2111201336.html

41 Surkov’s argument echoes Lenin’s arguments that Marxist-Leninism and its “inevitable victory” were also grounded in science (“physics”).

meanings of the word: violence declined in importance, and it was concealed from view by something else—that is, by the state’s need to encourage economic growth, provide social welfare, and guarantee personal security for its citizens. The eclipse of violence happened gradually. It was a slow, silent revolution, hidden in plain sight, but it was nonetheless a revolution as dramatic as any other in European history.42

Russia has completely missed Europe’s social and political transformation. Why? Professor Alexander Motyl points to theories that compare Putin’s Russia to Weimar Germany:

Other scholars argue that modern Russia’s expansionist drive comes from the way the former Soviet empire suddenly and comprehensively collapsed in 1991. Unlike the British and French empires, where the progressive loss of territory gave the imperial center time to adjust to being nonimperial, empires that collapsed in one fell swoop often retained the imperial ideology as well as many of the former empire’s important institutional and structural ties. The sudden collapse of the German Empire in 1918 is very instructive here: An unbroken imperial ideology mixed with resentment over lost status and territories was the toxic political and cultural cocktail that fueled the Nazis’ hyperimperialist war.43

Vladimir Putin on Peter the Great:

Peter the Great waged the Great Northern War for twentyone years. On the face of it, he was at war with Sweden, taking something away from it…. He was not taking away anything, he was returning. This is how it was. The areas around Lake Ladoga, where St. Petersburg was founded.

42 Sheehan, 2008: p. xx

43 Alexander J. Motyl. (2023 August 25). “Why We Should Not Bet on a Peaceful Russia.” Foreign Policy. Retrieved from: https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/08/25/russia-ukraineputin-prigozhin-negotiation-settlement-deal-peace-war-counteroffensive/

When he founded the new capital, none of the European countries recognised this territory as part of Russia; everyone recognised it as part of Sweden. However, from time immemorial, the Slavs lived there along with the Finno-Ugric peoples, and this territory was under Russia’s control. The same is true of the western direction, Narva and his first campaigns. Why would he go there? He was returning and reinforcing, that is what he was doing.

Clearly, it fell to our lot to return and reinforce as well. And if we operate on the premise that these basic values constitute the basis of our existence, we will certainly succeed in achieving our goals.44

—Vladimir Putin, to a group of students at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum in the summer of 2022

It is perhaps natural that Putin would look up to Peter the Great since, as he said in this speech, Peter founded Putin’s hometown. Peter is also a Russian hero who crushed two rival powers (Sweden and Poland-Lithuania)—and expanded Russia’s borders in the process! Peter made Russia great, and put it on Europe’s map as a power Europe could not ignore.

But if we unpack this little gem from Putin above, what becomes clear is he is really channeling the first independent Muscovite ruler, Ivan (John) III (15th century). Peter the Great (18th century) had founded St. Petersburg in part to get away from Moscow and break himself free from the entrenched boyar (aristocratic) power intrigues there. Instead, Peter had traveled throughout Europe and admired the West’s technologies and organizational capabilities. St. Petersburg was his way of Europeanizing Russia, of drawing the country closer to Europe and forcing Russia’s traditional power elites to adopt (Western) European manners of dress, behavior, and even thinking. Putin, in contrast, wants to sever Russia from Europe.

44 Vladimir Putin. (2022 June 9). “Meeting with young entrepreneurs, engineers and scientists” (English-language translation). Official webpage of the President of Russia. Retrieved from: http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/68606

Ivan III was a guy more on Putin’s wavelength. Having successfully broken Muscovy free from the Tartars in 1480, he essentially declared Muscovy to now be the sole legitimate heir to Kyivan Rus—by which Ivan meant that Muscovy now had the exclusive right to rule all former Rus lands. This essentially was his “Gathering of the Russias” policy. Never mind that the city of Moscow hadn’t even existed for most of Kyivan Rus’s history. To Putin, Ivan’s idea that Moscow can just grant itself the right to rule over others makes total sense.

Both Ivan and Peter had imperial dreams, but Peter sought to achieve them by emulating Europe and its successes. His vision for Russia was a European vision. Ivan and Putin, in contrast, embrace Moscow’s provincial, aristocratic, xenophobic ways that Peter rejected.

Finland’s foreign minister, Elina Valtonen, views Russian imperialism as more than a Putin problem:

I think what many haven’t perhaps realized is that this is not just Putin’s war. It seems that the Russian machinery, so to speak, has been preparing for this for a very long time. They have been actively waging war since [the 2008 invasion of] Georgia and 2014 against Ukraine, with the illegal annexation of Crimea. Of course, Putin has been in power during this time, but for more than two decades, he has built an infrastructure around this. And there could have been two decades for somebody [in Russia] to tell him that it’s not okay.45

There was a remarkable observation by Gau Yusheng, a former Chinese ambassador to Ukraine, who gave a speech at a forum hosted by the International Studies Department of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing shortly after the war started. (His speech was later

45 Ishaan Tharoor. (2023 September 25). “’This is not just Putin’s war’: How Finland’s top diplomat sees Ukraine.” Washington Post. Retrieved from: https://www. washingtonpost.com/world/2023/09/25/finland-war-nato-putin-defense-supportukraine-europe/?utm_campaign=wp_todays_worldview&utm_medium=email&utm_ source=newsletter&wpisrc=nl_todayworld

removed from Chinese websites.) He commented about Russia and its former empire:

The core and primary orientation of the Putin regime’s foreign policy is to view the former Soviet Union as its exclusive sphere of influence, and to restore the empire through integration mechanisms in various fields dominated by Russia. For this reason, Russia is duplicitous and reneges on its promises; it has never truly recognized the independence, sovereignty, and territorial integrity of other former Soviet countries, and frequently violates their territories and sovereignty. This is the greatest threat to peace, security, and stability in Eurasia.46

Finally, there is the question of whether Russia will ever be able to modernize and make the transition from empire to nation-state, like most of the rest of Europe has. Tomasz Kamusella is skeptical:

The Russian metropolis has been addicted to this imperial and exploitative economic model since the 18th century. Democracy necessitates decolonisation, which is a mortal danger to the empire. That is why, despite their progressive propaganda, in early 1918 the Bolsheviks ended the short-lived democratic experiment and dispersed the Constitutional Assembly. Similarly, in post–Soviet Russia a tank assault on the Russian Duma (parliament) in late 1993 spelt the end of any meaningful democracy in this country. In both cases empire won. Instead of genuine representation of the people’s will, the tsar was back, first as general secretary (of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union), and now as president (of the Russian Federation). Recently some members of the Russian elite even seriously proposed crowning the current Russian president as tsar.47

46 “Gao Yusheng, Former Chinese Ambassador to Ukraine: The Trend of the RussianUkrainian War and Its Impact on the International Order” (based on a machine-dependent translation into English). (2022 May 10). China Law Translate. Retrieved from: https:// www.chinalawtranslate.com/en/gao-yusheng-russia-war-comments/

47 Tomasz Kamusella. (2023 June 9). “Obstacles to Russian decolonization.” New Eastern Europe. Retrieved from: https://neweasterneurope.eu/2023/06/09/obstacles-to-russiandecolonisation/

A: As always, definitions are important. In his 1992 book, The End of History and the Last Man, Francis Fukuyama argued that from a political evolutionary perspective, democracy was about as good a system as humans could produce. In other words, with democracy, we’ve hit the end of the line. There’s no further to go. Now, some took this to mean that Fukuyama was claiming there would be no more conflict, that all of humanity would eventually see the democracy light and the primary human activity would be hugging other humans (and trees, and maybe spotted owls) and singing “Kumbaya.” But Fukuyama was right in the sense that nobody has (so far) come up with a better idea than democracy that delivers stability, higher living standards, social mobility, technological development, and maximum individual freedom. There are people arguing for older forms of society and government like theocracies, fascist dictatorships, kingdoms, etc., but those were all heavily discredited. Cuba may still claim communist supremacy, but how many people around the world today are trying to copy Cuba?

Why is this important? In their 2022 book, Spin Dictators: The Changing Face of Tyranny in the 21st Century, Sergei Guriev and Daniel Treisman argue something similar to Fukuyama, in essence that democracy has pretty much won the argument, so that people who espouse antidemocratic political beliefs must mask their authoritarian regimes in democratic clothing. Elections must be staged, political parties must exist (but be controlled), and all the outward trappings of a democratic society must be presented to cover up the reality of who has power and how it is wielded. For Stalin and Hitler, their dictatorships were naked and unapologetic. But in 2024, dictators—like Adam and Eve after eating that apple—feel the need for some strategically deployed fig leaves.

And Putin is Guriev’s and Treisman’s poster boy for a dictator wearing democratic clothing. As Chapter 10 in this book explores, Russia under Yeltsin was, at least briefly, a very real democracy, but one without any institutional history for support. Some believe Russian democracy died the day Yeltsin ordered the army to shell the parliament building in 1993, just two years into Russia’s democratic experiment. Others believe it limped on despite Yeltsin into the early years of Putin’s rule, maybe dying somewhere between the Second Chechen War (1999–2009) and oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s arrest in 2003. Others point to Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012 after his odd interregnum as prime minister. (Again, see Chapter 10 for details.) Any lingering elements of democracy that survived have steadily been eroded over Putin’s reign— and that erosion has rapidly accelerated since Putin ordered the invasion

of Ukraine. The Russian Army’s failures in Ukraine have clearly spooked Putin, prompting him to dispense with even the window-dressing of democracy and ensure that it is utterly, bluntly clear to anyone that he alone wields power in Russia.