Alan Blattberg

Alpern

David Netto is an independent architectural designer specializing in interior apartment renovations. He has lectured and published on the work of Rosario Candela. Christopher Gray is director of the Office for Metropolitan History, a research organization, and writes the weekly “Streetscapes” column in the real-estate section of the Sunday edition of The New York Times. Other books published by Acanthus Press: Great Houses of New York, 1880–1930. Michael C. Kathrens. Great Houses of Chicago, 1871–1921. Susan Benjamin and Stuart Cohen. Houses of Los Angeles, 1885–1935. 2 volumes. Sam Watters. The Main Line: Country Houses of Philadelphia’s Storied Suburb, 1870–1930. William Alan Morrison. Carrère and Hastings, Architects. 2 vols. Dream House: The White House as an American Home. Ulysses Grant Dietz and Sam Watters. The du Ponts: Houses and Gardens in the Brandywine, 1900–1951. Maggie Lidz. Houses of the Berkshires, 1870–1930. Revised 2011. Richard S. Jackson Jr. and Cornelia Brooke Gilder.

Rosario Candela has replaced Stanford White as the real estate brokers’ name-drop of choice. Nowadays, to own a 10- to 20-room apartment in a Candela-designed building is to accede to architectural, as well as social cynosure.” —Christopher Gray

The New York Apartment Houses of Rosario Candela and James Carpenter

Andrew Alpern is an architectural historian, an architect, and an attorney. This book is his fourth about apartment houses of Manhattan. He has also published five other books, the most recent being a fully-illustrated catalogue of the collection of architectural drawing instruments he donated to the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University. Alpern has published dozens of articles about architecture and the cityscape and has also published extensively on intellectual property and construction law.

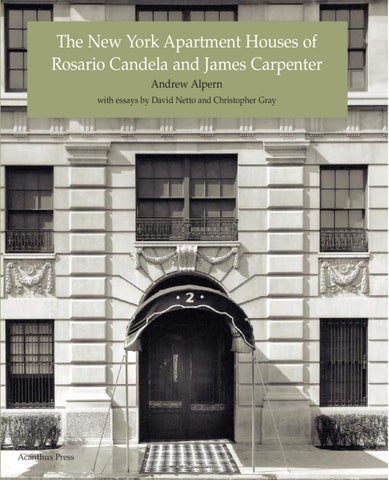

The New York Apartment Houses of Rosario Candela and James Carpenter Andrew Alpern with essays by David Netto and Christopher Gray

by Andrew Alpern Foreword by David Netto Preface by Christopher Gray The supreme addresses of choice in New York are on Park Avenue and on Fifth Avenue. But merely living on either of these famous boulevards is not enough. The ultimate aspiration is to dwell in a suite of rooms designed by one of the two masters of apartment-house design—Rosario Candela or James Carpenter. And they understood apartmenthouse construction inside and out. Working with enlightened builders, these men helped an affluent market understand and appreciate the amenities that separated their buildings from those of ordinary New Yorkers. They created the grand structures and lavish apartments that are now the standard living spaces of New York’s most successful people. The names Candela and Carpenter have become synonymous with well-proportioned rooms and imaginative layouts. They defined luxury in a way not equalled since their day, and the planning and design principles they developed are still strongly influencing apartment-house architects. Richly illustrated with 354 period photographs and floor plans, and with factual data and narrative, Andrew Alpern provides us with a fascinating architectural and social history of these great buildings. Supplemented by interior views, both vintage and recent, including newer interiors by some of the most important New York architecture and interiordesign firms, we are also able to see how people live in these great apartments. Through this book, Alpern shows us that the work of Candela and Carpenter is a contribution to the architecture of New York as significant as its great office skyscrapers and produced a parallel golden age of apartment-house construction and design.

Front cover photo: 2 East 70th Street, Wurts Brothers, courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York. Back cover: 770 Park Avenue, 15-room duplex, author’s collection.

The New York Apartment Houses of Rosario Candela and James Carpenter

Acanthus Press

With an important Introduction, supplemented by two additional authoritative essays, this delightful and informative book brings richly deserved recognition to two exceptionally talented architects of the early 20th century.