7 minute read

Out of this world

Out of this world

BY STEVE VOYCE

Advertisement

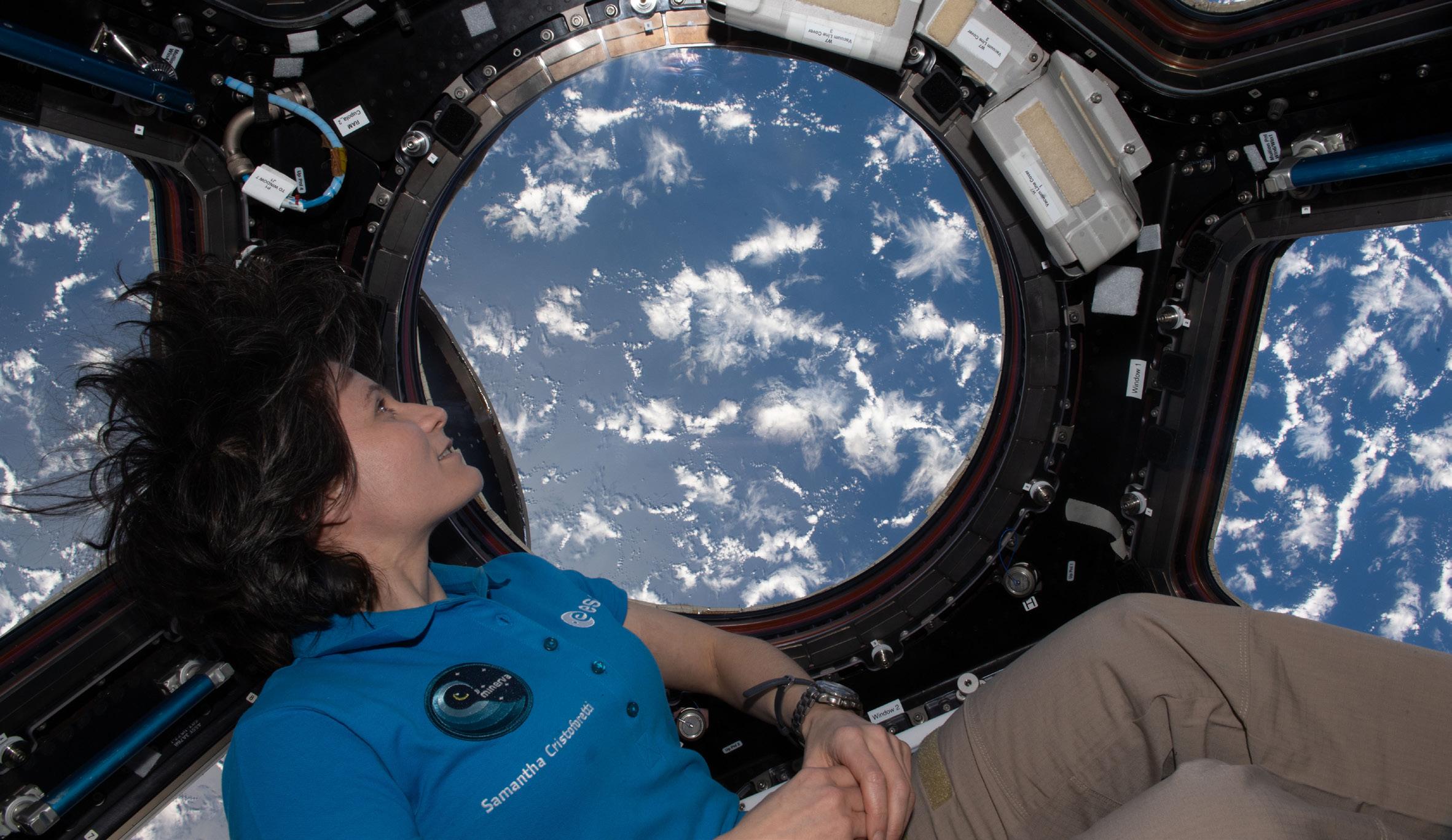

PHOTOS: ESA

Missions designed and tested at the European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC) in the Netherlands are circling Earth, landing on planetary bodies, and probing far into the Solar System.

ESTEC

Since its first foundation piles were laid between Noordwijk’s tulip fields and the sea in 1965, ESTEC has grown into the technical and organisational hub of the European Space Agency (ESA). On 3 April 1968, ESTEC was inaugurated by Princess Beatrix of the Netherlands. But the establishment had already been hard at work for a few years, meaning the first successful launch of an ESTEC-developed satellite was in May 1968, a month after inauguration.

After touring candidate sites across Europe in 1962, Norwegian nuclear physicist Dr. Odd Dahl proposed Delft as the site of ESTEC, adjacent to the Technische Universiteit Delft (Delft Technical University) that hosted the first European Space Research Organisation (ESRO) personnel. But land and labour were in short supply, and the site was waterlogged, offering less than ideal stability. In spring 1964, the Dutch government suggested a new site to overcome these problems in Noordwijk.

Here ground conditions were better, although there were initial worries about the adverse effects of fine sand and salty air on delicate machinery. Local tulip farmers also expressed concern that sandy soil disturbed by construction might harm their valuable bulbs. The first temporary buildings were in place by June 1964.

Collaborations

European nations have been collaborating on space projects since the 1950s. These international partnerships allowed knowledge, risk and cost sharing and grew into more formal agreements, which often ran parallel to one another. ESA was founded in 1975 from the merger of the European Launcher Development Organisation (ELDO) and the European Space Research Organisation (ESRO), both of which had been established in 1964.

ESA is Europe’s comprehensive space agency, active across every area of the space sector bringing benefits to everyday life and businesses. Its member states work together, sharing financial and scientific resources to achieve optimum results. Through Europe’s Spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana, ESA provides independent access to space for scientific and commercial missions.

Successes far and wide

The infrastructure and equipment assembled, together with the expert know-how of its personnel, make ESTEC a unique resource for Europe. The work done by teams skilled in every aspect of space engineering has enabled the creation of original communication, navigation, and information services, created new jobs and growth, and improved the lives of European and world citizens.

Sustainable space engineering

By the end of the 1980s more than 4,000 trees and shrubs had been planted around the ESTEC site. Ponds became havens for birdlife, but their purpose is utilitarian fed by runoff from the car parks, they provide a water supply for ESTEC’s fire service. ESTEC purchases 100% of its electricity from renewable sources, and buys ‘green gas’ with certified remediation of its carbon dioxide emissions, such as planting trees. They recycle, with food waste used for biogas production, and are launching a study into a future energy master plan, with inhouse production or co-generation an option.

ESA/ESTEC joins ACCESS

ACCESS is delighted to announce that ESA/ESTEC recently signed an agreement to join our Patron Programme. In taking this step ESA/ESTEC shows it is committed to supporting the successful settlement and integration of their international staff members and their families to their new lives in the Netherlands. ESA/ESTEC joins ACCESS’ other Patrons in providing some of the solutions new arrivals need, to feel settled in their new country of residence.

The last five decades have also marked the development of a vibrant space sector within the Netherlands. Dutch universities and research centres have played a key role in devising ESA missions, Dutch space companies have attracted customers from around the globe, and a growing number of Dutch start-ups are making innovative use of space discoveries in everyday life.

Make it big

ESTEC grew substantially during the 1970s. Until then, Europe’s satellites had been relatively small –a few hundred kilogrammes each, for lower orbits–but by expanding its test centre ESTEC could accommodate bigger satellites. These were large enough for Europe’s new Ariane 1 launcher.

ESTEC’s labs were also developing new materials and technologies for projects including ESA’s first geostationary satellites–for weather forecasting, telecommunications, and astronomy–and missions into interplanetary space: Giotto that visited Halley’s Comet and left the Solar System altogether, and »ESA’s go-it-alone Ulysses mission.

Working closely with NASA, as it always had, ESTEC also began involvement in human spaceflight, in Spacelab–a cargo bay module planned to transform NASA’s coming Space Shuttle into a productive orbital laboratory. This meant mastery of many new disciplines–hull shielding, life support and environmental control, automation and miniaturisation, and airlocks.

Growing up

As European space ambitions grew in the late 1980s, so did ESTEC. The priority was to manage large payloads, and this led to a new acoustic chamber, large cleanrooms, and a new shaker (One of the major risks faced by a satellite is from the high level of vibration during launch. Engineers test a spacecraft and its component parts under similar conditions using ESTEC’s electrodynamic shakers.). Also added were a new library, conference centre and restaurant–built by renowned Dutch architect Aldo van Eyck, a new main entrance, and recreation centre.

In the early 1990s, ESTEC gained a visitor centre (Space Expo) which made a big difference to its image locally and has become Europe’s oldest permanent space exhibition. Inaugurated in 1992, the Erasmus (European Robotics, Automation, Simulation and Mission Utilisation Support) Building was initially built for practising docking between spacecraft, but when those projects were cancelled, it found a modified purpose–as a resource for Europe’s scientific community to work with the microgravity research opportunities opened up by ESA’s involvement in the International Space Station.

New millennium

ESTEC’s scope of activities widened in the 2000s beyond the engineering of separate space missions as satellites were becoming parts of larger systems and services. ESTEC labs worked on satnav receivers, telecommunications user terminals and other massmarket devices.

Environmental data being returned by Envisat (the ‘Environmental Satellite’ launched on 1 March 2002 was the world’s largest civilian Earth observation satellite) demonstrated the potential of an operational environmental monitoring system. This resulted in Global Monitoring for Environment and Security, renamed Copernicus–developed in partnership with the European Commission–that combined groundbased data with results from a fleet of satellites.

To infinity…

Missions and technologies for the next two decades and beyond are already being worked on at ESTEC–looking at changing tools and ways of working for the next generation of engineers.

By 2018, ESTEC had a workforce of 2,500 (both auxiliary and support staff) along with an additional 300 service personnel. ESTEC has always stimulated the Dutch economy–some 60% of ESA spending goes through the organisation–and thanks in part to ESTEC’s presence, the Dutch economy is estimated to receive a five-fold annual return on its ESA investment. The next two decades see the planned launch of Galileo Second Generation navigation satellites and construction of the international Deep Space Gateway in halo orbit around the Moon. Both will be serviced by the NASA-ESA Orion spacecraft, intended as a staging ground for robotic and human missions to the lunar surface and testing technologies for a next-decade Mars mission. «