Introduction

For 30 years I’ve driven by the barns of the St Croix River Valley, but I didn’t really see them until I started sketching . These barns stand as a testament to a bygone era . To the way farming used to be . To an age when land was currency—ticket to a livelihood .

Today, a few of these classic old barns have been upgraded or preserved and repurposed, some provide wedding venues or support retail sales . Others, like mine, have been maintained but used only for storage or an occasional barn dance or celebratory dinner . On working farms, old barns are put to use but not as originally intended, which was for storing hay in the haymow and cows or cattle and young stock and horses or mules below . Many return to earth, little by little, until one day the barn you’ve been motoring by is now flat, marked only by a silo .

This book takes you on a journey back in time .

Native Americans and their ancestors lived in the Valley for 10,000 years, European explorers came in the 1600s, fur traders followed them, and lumber barons arrived in the early 1800s . Although not all of these groups built barns, they all impacted barn building .

The story of the barns themselves is the story of migrants from New England and immigrants from Europe, all seeking land . It is the story of agriculture and how it changed in the hundred years from the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s .

ORO Editions

Map of the St. Croix Valley

Good sized dairy barn near Holyoke, Minnesota, no longer in use. Owner was offended that I sat in the right-of-way and sketched the barn. She called the sheriff.

Gambrel-roofed dairy barn with three additions near Center City, Minnesota.

This Gothic arch dairy barn near Dresser, Wisconsin, is in the process of collapsing and the farm now specializes in Holsteins as beef cattle

The St Croix River

The St . Croix River takes its water from 18 counties—nine in Minnesota and nine in Wisconsin—before offering it to the Mississippi . Its watershed covers approximately 7,800 square miles, an area 50 percent larger than the state of Connecticut . The tributaries add up to 2,000 miles of waterways, more than the distance from the twin cities of Minneapolis and St . Paul to Miami, Florida .

Map of the St Croix River Watershed

This barn north of Taylors Falls, Minnesota, with sheds both sides, has been around a long time.

Source: United States Geological Survey.

Fancy dormers and lightning rods on this old a dairy barn south of Lindstrom, Minnesota.

Abandoned hopes near Ubet, Wisconsin.

Map of Major Tributaries and Surrounding Counties

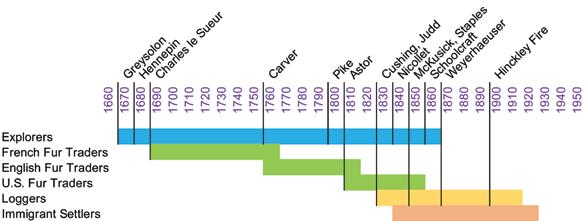

Timeline of European Intrusions European Explorers

European explorers traveled in the Valley for two hundred years . In 1679, the Frenchman Daniel Greysolon Sieur Dulhut was the first European to record his exploration of the St . Croix Valley, claiming the wilderness for France . He also got to the Bois Brule River via the time-honored portage—now on the National Register of Historic Places—that links the two rivers in Northern Wisconsin .

The Continental Divide, known as the Laurentian, separates the watersheds of the Bois Brule River and the St Croix River . The Brule flows north to Lake Superior, and its water goes through the St . Lawrence Seaway to the North Atlantic Ocean . The St Croix River flows south into the Mississippi River and eventually to the Gulf of Mexico . Indigenous peoples had followed the St Croix-Brule trade route from Lake Superior to the Gulf in canoes for generations .

Early explorer Récollet Father Louis Hennepin wrote about the St Croix River in his book, Description de la Louisiane, published in

1683, “We named it the Rivière du Tombeau … because the Savages bury’d one of theirs, who was bitten by a Rattle-Snake . ”

Hennepin’s name, River of the Tomb, did not catch on, however, and it was Nicolas Perrot, who coined the name St Croix, using it in a 1689 proclamation in which he claimed for France all the interior of North America including the Rivière de Sainte-Croix. The source of the name is unclear—it could have come from a cross marking the grave of a French voyageur or boatman buried near the mouth of the river or from the Maltese Cross rock formation at the Dalles below St Croix Falls, Wisconsin .

In 1767, former British Army Captain Jonathan Carver, the first and only British explorer to traverse the St Croix River, came into the Valley with his entourage on the way to Lake Superior in a failed attempt to find the Northwest Passage to the Pacific Ocean . Carver County, Minnesota, bears his name .

Faded red basement barn near Dresser, Wisconsin.

Barns of the Valley

Finally, it’s time to talk about barns . In the 1800s and early 1900s, barns were farmers’ banks, symbols of prosperity . Houses were secondary; they didn’t contribute to the bottom line . The barns that rose up in the St Croix Valley sprang from antecedents in New England, which in turn had come from the Old World . Immigrants also built in the ethnic traditions of their homeland .

Barns were often the setting for gatherings—witness Per Berg’s haymow used to launch a church . Barn raisings were common— all the neighbors pitched in and enjoyed the farmwife’s cooking . A lso barn dances, celebrations, even Thanksgiving dinners . The majority of the classic barns we see in the Valley today were built during the century from 1860 to 1960, a time of major change— from subsistence to wheat, to dairy, to beef, to specialization .

Wheat Barn

The early settlers were subsistence farmers—what else could they be? —feeding their families was their foremost concern . Anyway, there was little or no market for a cash crop, and even if there had been, there were no roads to get it there, and railroads wouldn’t

CROIX VALLEY

be around for decades . Ultimately a changeover to wheat, the most nourishing of the grains, took hold as a money crop . Loggers were the first customers, followed by city folk . By 1880, 70 percent of Minnesota’s tilled acreage was in wheat .

W heat as a money crop attested the poverty of early farmers—it could be raised with minimal investment in both labor and material . Over time the soil wore out with this mono-agriculture system . Lack of production became a concern, and scientific farming practices were touted . Nevertheless, during the Civil War, as the price for wheat tripled, farmers bought thrashing machines and mechanical reapers to increase production and profits . But by the 1870s, the handwriting was on the wall—production had gone from 20 bushels per acre to just six .

It was easy to broadcast wheat seeds once the plow had done its job . Tree branches or a harrow smoothed out the soil . Harvesting required cutting, using a one-handed sickle or two-handed scythe or perhaps a cradle which could catch the cuttings . These were wrapped into sheaves and stacked into shocks to dry in the field .

Once dry, the grain head was dislodged from the straw by threshing with flails or having horses or cattle tramp on it . Winnowing separated seed from chaff by pouring it from one container to another or throwing it up into the air and letting the wind blow away the chaff .

By 1843, Lemuel Bolls had started the first gristmill in Afton, Minnesota; another soon followed on the Willow River . Neighboring farmers no longer had to grind their own flour .

The migrating Yankees from New England built gable-ended, three-bay English threshing barns— bays defined by heavy timber ‘bents’ supporting the roof . The center threshing bay had tight fitting, structurally supported tongue and groove plank flooring . At each doorway, a horizontal board fixed to the floor stopped the grain from escaping . It was called, guess what? … a threshold . As Charles Calkins and Martin Perkins write in Barns of the Midwest :

The door openings were large enough to allow a fully loaded wagon, pulled by a team, to enter and exit the central bay. Besides serving as a sheltered location to unload the harvest, the drive-through bay also was the surface upon which the grain crop was thrashed or separated … The two sets of doors were adjusted to regulate the draft needed to carry the winnowed chaff from the threshing floor.

Grain was stored in bins or jute gunny bags in one of the side bays . The other bay was used for storing unthreshed wheat or perhaps other things such as straw, cattle, or horses .

ORO Editions

New Barns

Of course, the old barns we love—gable, gambrel, or gothic arch roofs, two-story with haymows—aren’t built anymore . New barns respond to new functions: no need for a haymow, so milking can be done in a one-story building; and for row crops, there is no need for a barn at all . In fact, not only are these barns biting the dust, but even the name barn is disappearing, to be replaced by the term general utility building .

Steel buildings became standard during and after World War II . Quonset huts with their rainbow rooflines were developed for the war, and afterward factories had plenty of capacity—selling to farmers presented a good market . Farmers could order the prefabricated pieces and bolt them together themselves .

Pole barns had been developed in the 1930s but not patented until 1953 . These gable-ended, steel-clad buildings used creosote treated poles, 2 by 4 framing, and pre-painted sheet metal roofing and siding . They were relatively inexpensive and easy for farmers to build themselves . Dirt floors could later be covered with concrete .

Quonset type shelter near Scandia houses a tractor and wagon.

Quonset type bank barn with silo out by its lonesome in a hayfield in Washington County. Apparently other buildings survived.

Quonset barn, perhaps used as a granary or machine shed near Scandia.

Section through a steel building.

A step up from pole barns, serious steel buildings are well engineered, larger scale, supported by light-gage open-web steel bents (remember the heavy timber bents of the early threshing barns?) .

They use long span, pre-painted steel roof deck, vertical prepainted steel siding, concrete slab-on-grade, and footings or piles extended below frost line .

The big barn is gone; a Quonset hut building peeks out on the left, and perhaps a repurposed claiming shanty on the right.

Windmills

In Europe, windmills had been used for centuries to mill grain and also to pump water in the Low Countries . Images of the Dutch windmill are well known . Germans carried this technology to the New World and built Dutch-type windmills for grinding grain . Smaller windmills were used to pump water from handdug wells, run feed mills and sawmills, and to generate electricity . The first windmills were made of wood and sat atop wooden towers, but galvanized steel eventually became standard .

Our farmstead came with an Aermotor. The shaft was bent, and the mill was lumpy and noisy as it rotated. One night, high winds blew one blade off the mill followed by another and another. By morning all the blades were on the ground, and the mill just stood there naked. Thankfully, insurance gave us a new windmill. Our neighbor, Doug, who grew up on the farm just north of us, had never climbed up to oil their windmill. He volunteered to oil ours, and when he got up to the platform, he just sat there for the longest time before pulling up the bucket with the oil in it. We asked him why, and he said, “Had to wait till my knees quit shaking.”

The windmill and self-regulating pump—which stopped pumping once a stock tank, storage pond, or water tower was full—had been invented by Daniel Halladay in 1854 . His pump design remained in use for nearly a century . The pumping is a simple piston in the well, opening on the downstroke and closing on the upstroke as water is drawn upward .

In 1888, inventor LaVerne Noyes and entrepreneur Thomas Perry got together to form the Aermotor Company of Chicago, Illinois . The Aermotor windmill underwent various refinements, and by 1915 a self-oiling windmill was in production, requiring annual rather than weekly lubrication .

A farm near Scandia still has its windmill.

Windmill on US-8 near Taylors Falls.

Basic design consisted of a wheel with concave steel blades and a tail piece or rudder which kept the mill facing the wind . The tail also turned to slow the rotation in strong winds . A cable and lever applied the brake and placed the tail parallel to the mill so it presented a narrow profile to the wind and would not be blown apart in a storm . Through a pitman gear, the circular motion was converted to an up-down motion that operated the pump producing 1,500 gallons of water a day .

In 1930, there were 600,000 windmills in use . They could be purchased as kits sold by Sears Roebuck or directly from Aermotor or other manufacturers . However, Rural Electrification put an end to the windmill by bring electricity to farms . An electric pump could produce thousands of gallons a day and didn’t entail a hazardous climb to the top of the windmill tower for maintenance and oiling . Farm on MN-97 with enduring windmill.

Abandoned farm near Harris in winter. Windmill still stands, commemorating a farm that was.

Farming Today

Family Farm

People ask, “Whatever happened to the family farm?” The answer is it’s still here, just different . Ninety-nine percent of all farms in the U .S . today are owned by families . However, the traditional family farm was owned, lived on, and worked by the family . Most of the income came from the farm, and the family made all the decisions about the farming operation . This is no longer the case—now it’s corporate agriculture .

W hat happened is that as farming became a larger enterprise, it became very specialized, and it became big business . In the 1930s there were 6 .5 million farms; in 2017 there were just one million farms—not counting two million hobby farms .

In my neighborhood south of Lindstrom, Minnesota, over the past 30 years, I’ve seen farmers who’ve retired and broken up their farms . Single-family houses on five acre lots have sprouted up . The remaining open land is usually farmed—huge John Deere tractors appear for spring planting, spider-like machines come by in the summer to spray the row crops, and combines and grain semitrucks appear for harvesting in the fall . But there aren’t barns or farmhouses anymore, and I don’t know exactly who’s doing the farming .

Red barn and supporting buildings on a snowy day. Near Chisago City, Minnesota.

Agribusiness

What is agriculture’s share of the overall U .S . economy? USDA says:

In 2019 agriculture, food, and related industries contributed $1.109 trillion to the U.S. gross domestic product, a 5.2-percent share. The output of America’s farms contributed $136.1 billion of this sum—about 0.6 percent of GDP.

Agribusiness is huge compared to farming itself, seven times larger in fact . Examples include farm machinery producers like Deere & Company, seed and agrichemical manufacturers like Monsanto, food processing companies like Archer Daniels Midland Company, as well as farmers’ cooperatives, ethanol plants, and animal feed producers .

Orange barn in Chisago City painted and roofed to match the structural glazed tile first story.