Chris Stephens

Who speaks of art speaks of poetry. There is no art without a poetic aim.

Édouard Vuillard

This book focuses on the small, early works of Édouard Vuillard, from the 1890s and the first years of the twentieth century. Vuillard (1868–1940) was at that time in his twenties and early thirties. Yet, for the novelist Julian Barnes, this period of his painting was ‘one of the most supreme and complete explosions of art in the last two hundred years’.1

With a number of friends, including Pierre Bonnard and Maurice Denis, Vuillard was a member of the Nabis, a group committed to an art that was representational but design-orientated. Just as there is a tension between the implied drama of his works and their abstract qualities, so there was in Vuillard’s art of this period an extreme

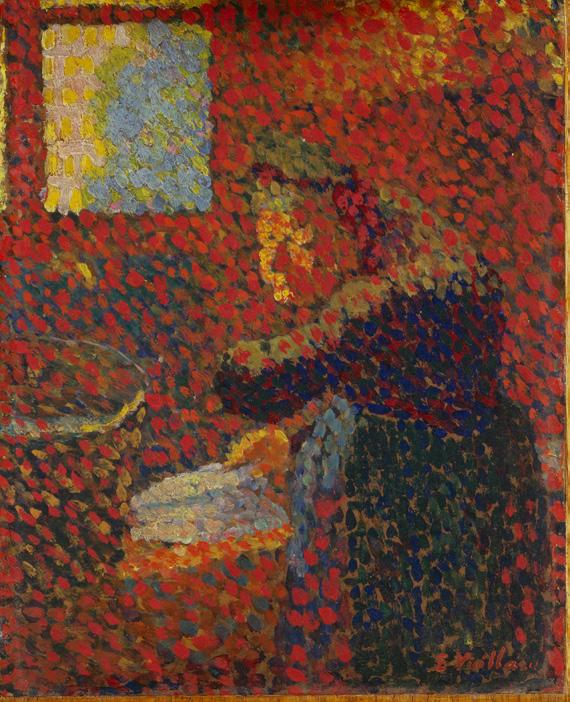

Opposite: detail from Two Seamstresses in the Workroom, 1893 (cat. 9)

Previous page: detail from Two Women in a Public Park, 1895 (cat. 10)

Page 1: detail from Woman Reading in the Reeds, 1909 (cat. 36)

contrast between large decorative schemes that he worked on for private clients, and for the theatre, and the intimacy of the small paintings he made for himself. It is on the latter, intimate studies of the private realm for the most part, punctuated with landscapes, that the current selection concentrates. The diminutive size of the works does not imply any lack of ambition, however, nor some minor status. Though unquestionably shy, Vuillard was not as hermit-like as his paintings would suggest. He largely painted the interior world of the apartments shared with his mother and sister, or his friends’ homes, but through choice. His art is a celebration of the mundane. Yet in its succinct intimacy it is also highly complex, if not contradictory. There is a warmth in his close observation of familiar individuals and activities and yet, as Barnes noted, ‘his interiors are too dark, too hermetic, vaguely claustrophobic. However charmingly, they exclude: we are not especially wanted here.’2 He is a great colourist, balancing hues as well as he does patterns, but the writer André Gide observed how ‘he never strives for brilliant effect; harmony of tone is his continual preoccupation’.3 Carefully constructed and composed, his pictures nonetheless have the appearance of chance, like a poor photograph. They are, for the critic John Russell, ‘small masterpieces

of the apparently informal and the seemingly offhand ... in which the action scutters off-centre and the image has, even after three-quarters of a century, a startling asymmetry’.4 Yet, in Vuillard’s hands, the quotidian becomes almost sacramental. In balancing form and content, psychological drama and abstraction, his pictures are about as close to poetry as any artist’s, and all the more brilliant for their understatement and the near imperceptibility of their craft. [

This book coincides with an exhibition at the Holburne, Bath in summer 2019. I have been fortunate to work on the show with my colleagues Nina Harrison Leins and Sylvie Broussine. I am delighted that such an authority as Belinda Thomson agreed to write for this book and I would like to thank Mathias Chivot, Director of the Archives Vuillard, for his help with this publication. As ever, we are indebted to all of the lenders; Thomas Gibson and his family have been especially generous and I am grateful to Brett Gorvy, too, for his help. I would like to thank the Vuillard Exhibition Supporters Group for supporting the project, in particular Thomas Gibson and Manfred and Lydia Gorvy, and the Holburne Exhibitions Circle.

Belinda Thomson

1894 was a key year for Édouard Vuillard. He had recently shown small groups of works in various exhibitions, attracting the admiration of a wide range of critics.1 He successfully completed an ambitious decorative scheme, the nine Public Gardens panels for the dining room of the businessman and journalist Alexandre Natanson.2

This effectively translated onto a large surface, using the medium of distemper, the practical experiments he had been making on a much smaller scale, using oil on cardboard supports (e.g. cats.1,3,4).

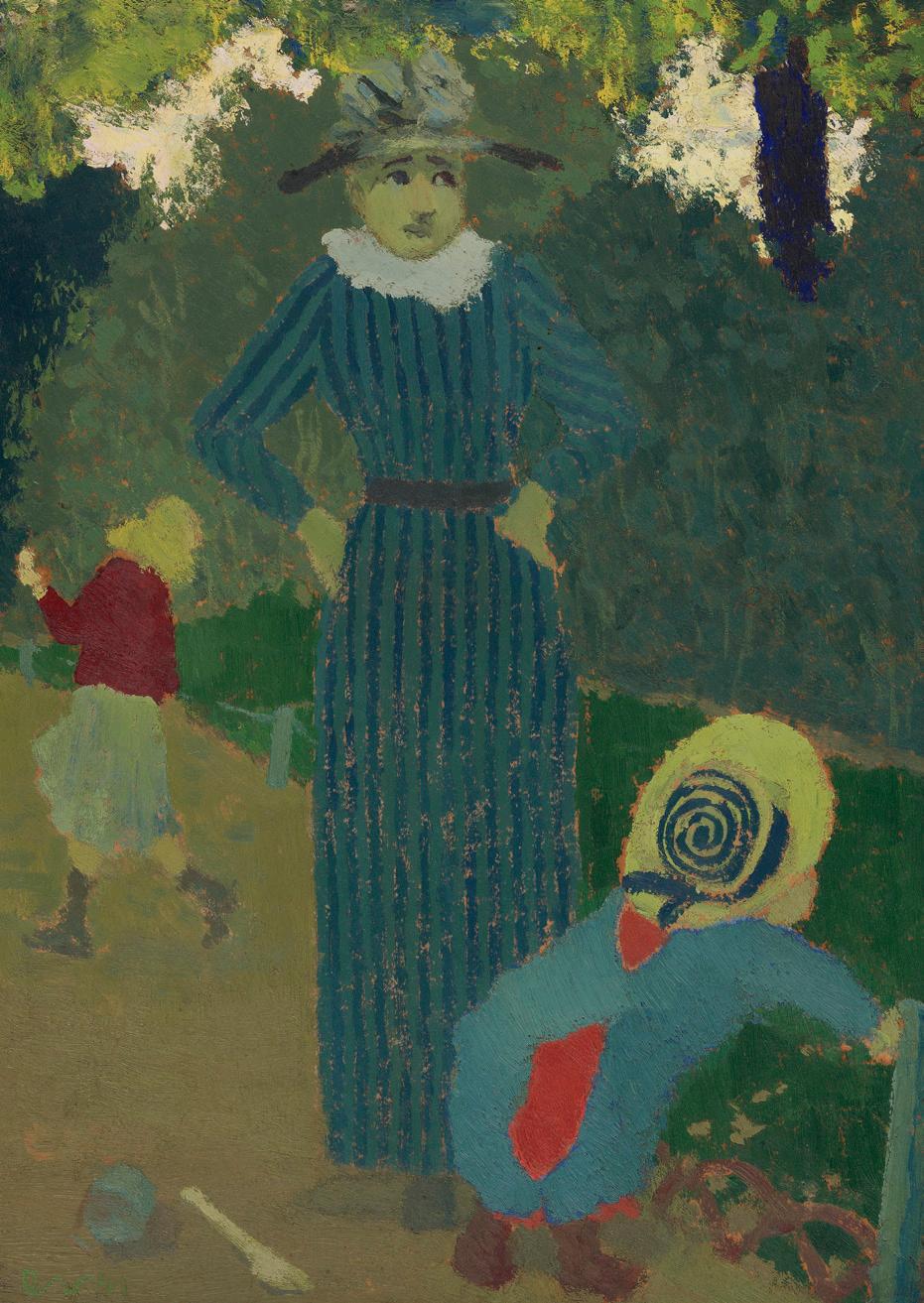

Moreover he arrived at certain important conclusions in his theoretical thinking. Although by nature reflective and serious, Vuillard was by no means a propagandising theorist like fellow Nabis Maurice Denis and Paul Sérusier.3 Throughout his career, he set down his Opposite: detail from In the Park, The Straw Hat, 1891 (cat. 3)

thoughts in telegraphic style in his private journal. He was striving for self-knowledge through personal affirmations which could, if necessary, shield him from the more forceful arguments of his comrades.

The significance of Vuillard’s æsthetic aperçus for his creativity as a painter is only gradually being assimilated and assessed by scholars.

Interrogating vulgar taste

One such note from 1893, essentially a rhetorical question, has been regularly quoted:

Why is it always in the familiar places that the mind and the sensibility find the greatest degree of genuine novelty?

Novelty is always necessary for life, for consciousness.4

The following year, on 26 October, Vuillard developed this idea, interrogating the ways in which his imaginative powers and æsthetic emotions responded to his everyday, familiar surroundings.

One lives surrounded by decorated objects. In the most ordinary interior, there’s not an object the form of which doesn’t have an ornamental pretension – and most of the

time the form hides its function from us under these irrelevant embellishments.

He drew a distinction between the inherently ornamental quality of a bunch of chrysanthemums he was not interested in painting because it, ‘requires no effort … to grasp its aspect, forms and colours’, and his desire to make a picture comprised of forms and colours that one had to struggle to grasp and which made more complex demands upon the imagination and mind of the person contemplating it. The ornamental interest that attaches to other objects, a figure, a pot, for example, is less crude, it’s not about the vibrant colours, there is no multiple repetition of similar forms (like petals).

He proceeded to enumerate in Balzacian detail, from the vantage point of his bed, all the varied aspects of his bedroom that caught his eye: the white painted ceiling, the central rose with its vaguely 18th century arabesque motifs, the mirrored wardrobe opposite, the cracks and mouldings of its wood and those of the window surround, their proportions, the curtains, the

chair in front of them with its carved wooden back, the wallpaper, the handles of the open door, glass and brass, the wood the bed is made of, the wood of the screen, the hinges, my clothes on the foot of the bed; the four elegant green leaves in a pot, the inkwell, the books, the curtains of the other window, the walls of the courtyard seen through them, the different perspectives produced by the two windows, one with a small segment of sky making lines parallel to those of the window, in the other, forming a perpendicular angle, the impression one gets from just that corner. (As for the curtains, the differences and patterns that result from the greater or lesser tautness of the threads. Merely comparing the qualities of each of these objects I experience a thrill…)

This inventorying led him to a telling conclusion:

It’s just as difficult, indeed more so I think, but very instructive to understand a vulgar thing (I wouldn’t call it simple any more) an ordinary thing that has moved you as it is a thing that is widely accepted as beautiful.

In a further observation he sought to define that vulgarity or bad taste:

I was struck by the abundance of ornament in all these objects. They are what one calls in bad taste and were they not familiar to me I would perhaps find them unbearable.

Reading these notes, one is mindful of the many exquisite works in which Vuillard tested this notion, managing to distil his pleasurable emotion in ordinary, ephemeral objects of no intrinsic merit to convey his sense of the poetry in the everyday (e.g. cats. 5, 8, 9). But his reflections, with their echo of the Arts and Crafts idea of form following function, also pose the question of where he derived his notions of what constituted good and bad taste. During the 1880s a number of influential French manuals on decoration were published.

Charles Blanc’s authoritative Grammaire des arts décoratifs (1882) is likely to have been required reading for École des Beaux-Arts

students such as Vuillard and he may also have known the art critic Émile Cardon’s practical L’art au foyer domestique (1884). Paris’s population had swollen rapidly in the late nineteenth century, and these authors clearly sensed a need in even the most modest households for guidance on how to improve their domestic surroundings, not least because of the cramped conditions in which people were

1: Grandmother at the Kitchen Sink, c. 1890

living and the proliferation of cheap, machine-made household objects. Such readers, it was assumed, would appreciate some rules of thumb. Both texts are clear about what constitutes good taste and warn against the dangers of vulgar, cheap, gimcrack decorative solutions. Readers are urged to rid their homes of objects that are neither useful nor beautiful, Cardon even asserting, in what sounds like a counsel of perfection, that ‘the objects which constantly fall under the eye must be perfect in form, design and finish; this is the

only way of forming or completing the education of taste.’5 Women, he opined, were the ultimate arbiters of taste, capable of restoring the love of home known by previous generations.6

In his determination to remain true to what he found or perceived in his immediate environment, however much in ‘bad taste’ and pointlessly embellished, Vuillard was a naturalist not an idealist. Indeed there is a strong argument for saying he adhered, from the outset, to the position of Edmond Duranty (1833–1880). In La Nouvelle Peinture Duranty specified just what it was that in his view constituted modernity (which, without naming him, he associated closely with the work of Edgar Degas): it was the artist’s ability to convey a subject’s whole personality and social milieu through a telling contour, gesture or characteristic assemblage of ill-assorted but lived-in objects. 7 That Vuillard identified strongly with this text became clear after his death: he was the dedicatee of Floury’s 1946 reprinting of La Nouvelle Peinture . 8 When Maurice Denis was drafting his Défnition du néo-traditionnisme in 1890, and categorically downplaying the importance of subject matter, Vuillard was evidently pressing Duranty on his attention, conscious of the contradictions it set up. 9 His journal for July 1890 reveals his

2. The Family After the Meal, also known as The Green Dinner, 1891

The Two Sisters-inLaw, 1899

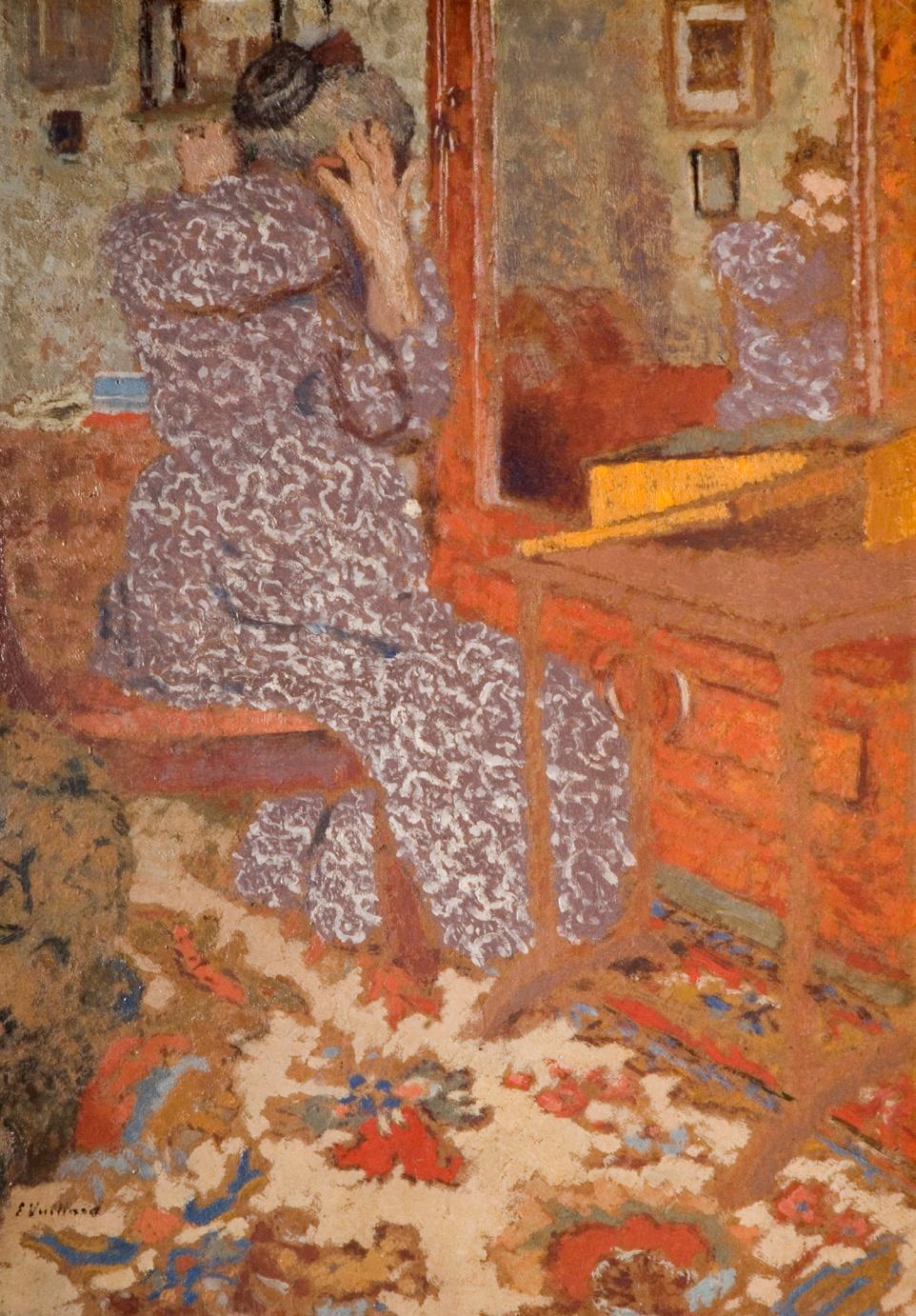

Arranging her Hair, 1900

SC numbers refer to Antoine Salomon and Guy Cogeval, Vuillard: The Inexhaustible Glance: Critical Catalogue of Paintings and Pastels, Milan, 2003

Figures

1. Grandmother at the Kitchen Sink, c. 1890, oil on cardboard mounted on hardboard, 22.5 x 18.3 cm, Private collection, London, SC II-3

2. The Bridal Chamber, 1893, oil on cardboard, 32.5 x 53 cm, Private collection, SC IV-133

3. Manufacture Isidore Leroy, machine printed coloured wallpaper from an album, 1878–9, 47 x 50.5 cm, Musée des Arts décoratifs, Paris, 51820

4. Family Evening, 1895, oil on canvas, 48 x 65 cm, Private collection, SC IV-211

5. Woman Sweeping at 346 rue Saint-Honoré, 1895, oil on cardboard, 33 x 50 cm, Private collection, SC IV-190

1. The Game of Shuttlecock, c. 1891, oil on cardboard, 18 x 24 cm, Private collection, SC V-3

2. The Family After the Meal, also known as The Green Dinner, 1891, oil on cardboard, 34 x 49.5 cm, Private collection, SC IV-4

3. In the Park,The Straw Hat, 1891, oil on cardboard, 32 x 22.5 cm, Carlisle Fine Art, SC V-1

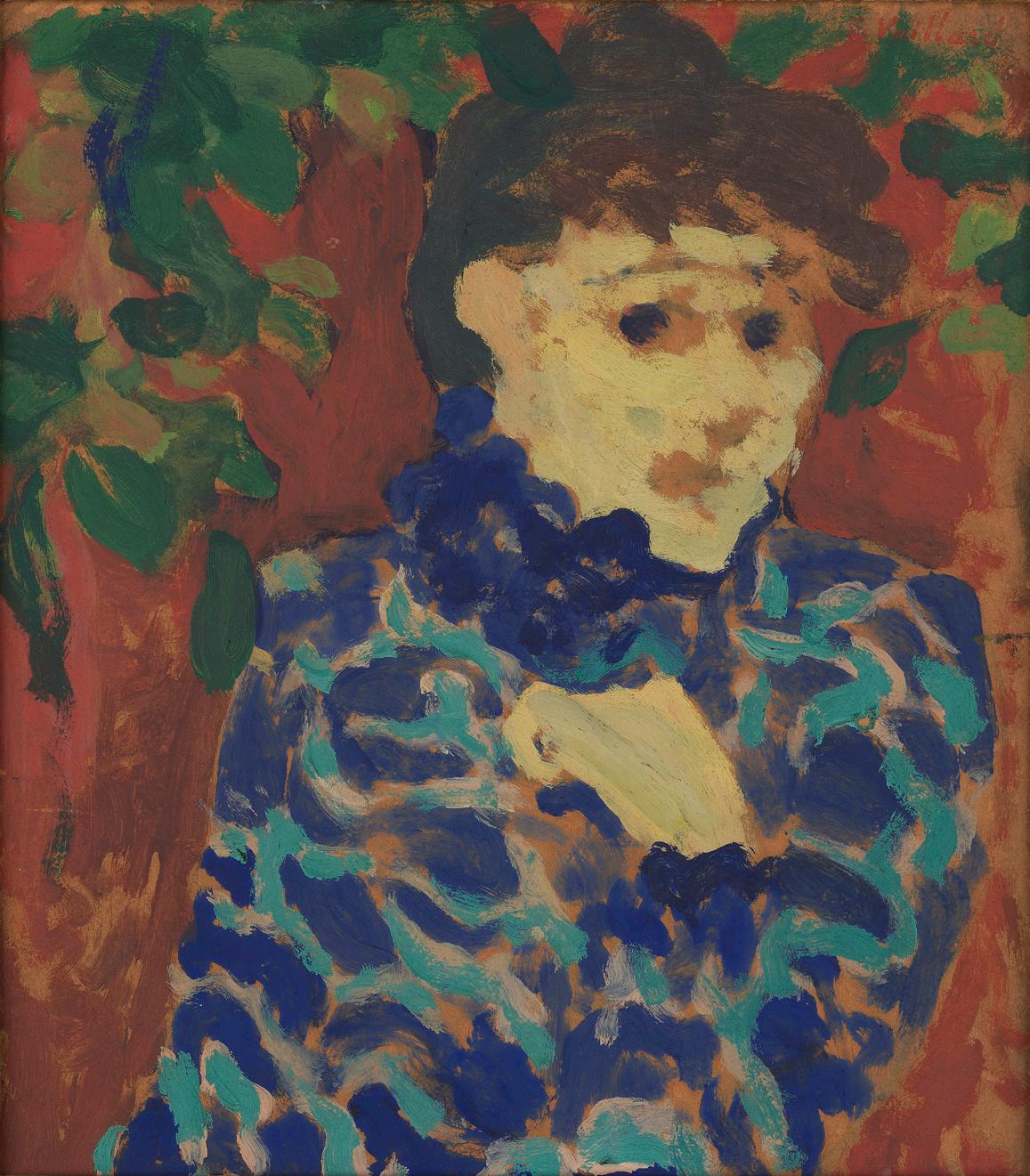

4. Woman in a Blue Brocade Blouse, c. 1892, oil on cardboard, 25 x 22 cm, Miles, Sebastian and Hugh Gibson, SC V-9

5. The Ear, c. 1892, oil on board, 12 x 15.5 cm, Thomas Gibson, SC IV-32

6. Woman by an Open Door, 1893, oil on cardboard, 27 x 22 cm, Miles, Sebastian and Hugh Gibson, SC IV-114

7. The Chat, 1893, oil on canvas, 32.4 x 41.3 cm, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, GMA 2934, presented by Sir Alexander Maitland in memory of his wife Rosalind 1960, SC IV-134

8. The Artist’s Sister with a Cup of Coffee, 1893, distemper on card, 35.5 x 29.1 cm, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, PD.1-1994. SC IV-94

9. Two Seamstresses in the Workroom, 1893, oil on millboard, 13.3 x 19.4 cm, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, GMA 3583, Purchased with assistance from the Art Fund (Scottish Fund) and the National Heritage Memorial Fund 1990, SC IV-146

10. Two Women in a Public Park, 1895, oil on board, 24.8 x 27.3 cm, Private collection, SC V-59

11. French Can-Can, c. 1895, oil on cardboard, 20.3 x 19.05 cm, Private collection, SC III-51

12. Road Skirting a Forest, c. 1896, oil on board laid down on panel, 40 x 50 cm, Thomas Gibson, SC VI-21

13. The Manicure, c. 1898, oil on cardboard mounted on panel, 35.5 x 30 cm, Southampton City Art Gallery, 2/1968, SC VI-42

14. Cover for the Album Landscapes and Interiors, 1899, lithograph on paper, 51 x 40 cm, British Museum, London, 1949,0411.3595

15. The Game of Checkers, from Landscapes and Interiors, 1899, lithograph on paper, 33.5 x 27 cm, British Museum, London, 1949,0411.3596

16. The Avenue, from Landscapes and Interiors, 1899, lithograph on paper, 31 x 41.1 cm, British Museum, London, 1925,0314.60

17. Through the Fields, from Landscapes and Interiors, 1899, lithograph on paper, 24 x 35 cm, British Museum, London, 1951,0501.27

18. Interior with Pink Wallpaper I, from Landscapes and Interiors, 1899, lithograph on paper, 35 x 27 cm, British Museum, London, 1949,0411.3599

19. Interior with Pink Wallpaper II, from Landscapes and Interiors, 1899, lithograph on paper, 34.5 x 27 cm, British Museum, London, 1949,0411.3598

20. Interior with Pink Wallpaper III, from Landscapes and Interiors, 1899, lithograph on paper, 34 x 27 cm, British Museum, London, 1949,0411.3600

21. The Hearth, from Landscapes and Interiors, 1899, lithograph on paper, 34 x 28 cm, British Museum, London, 1949,0411.3601

22. On the Bridge of Europe, from Landscapes and Interiors, 1899, lithograph on paper, 30 x 34.5 cm, British Museum, London, 1949,0411.3602

23. The Cook, from Landscapes and Interiors, 1899, lithograph on paper, 35 x 27 cm, British Museum, London, 1949,0411.3604

24. The Two Sisters-in-Law, from Landscapes and Interiors 1899, lithograph on paper, 37 x 29 cm, British Museum, London, 1949,0411.3605

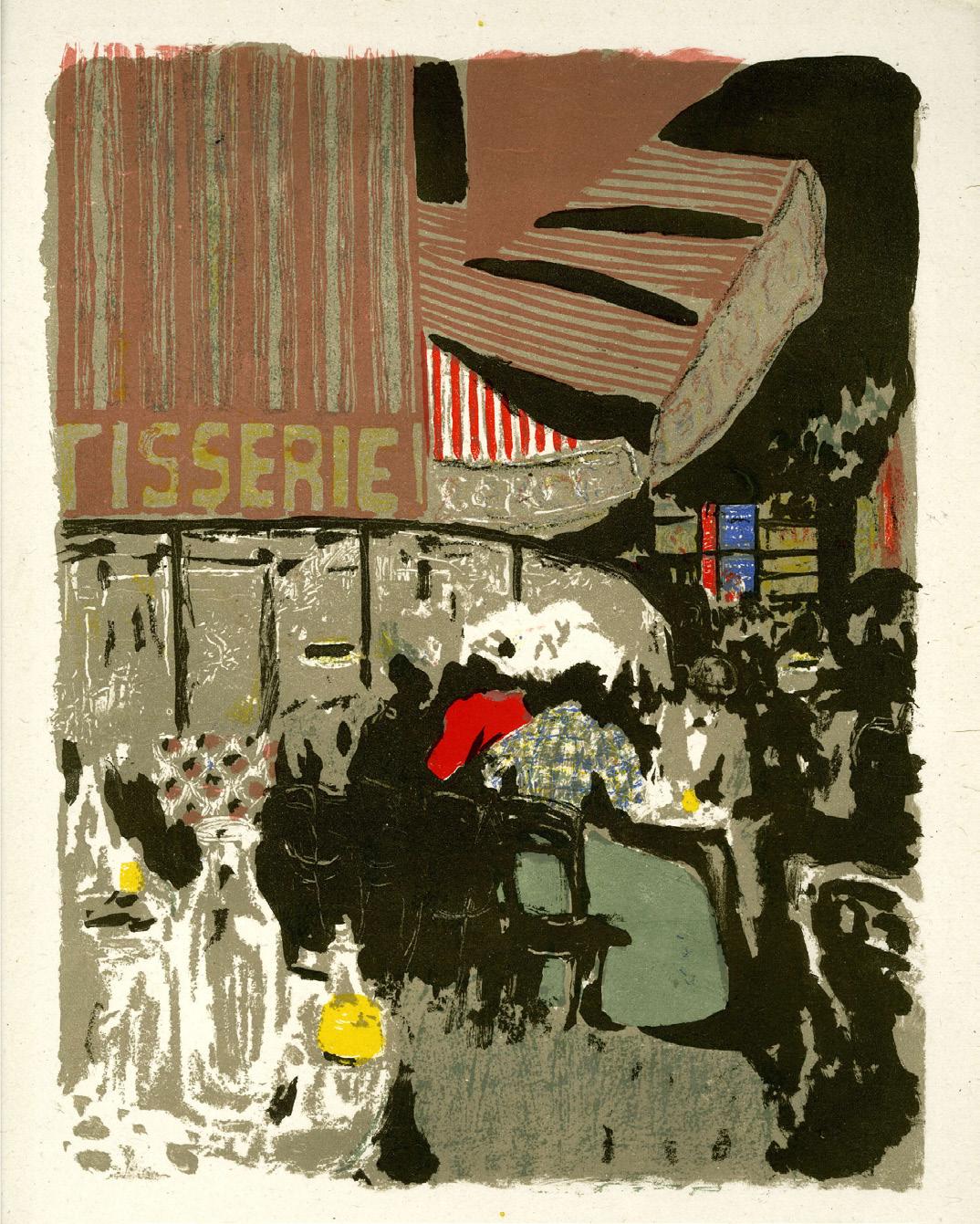

25. The Pastry Shop, from Landscapes and Interiors 1899, lithograph on paper, 36 x 28 cm, British Museum, London, 1949,0411.3603

26. The Candlestick, c. 1900, oil on millboard, 43.6 x 75.8 cm, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, GMA 2935, Presented by Mrs Isabel M. Traill 1979, SC VII-125

27. Madame Vuillard Arranging her Hair, 1900, oil on cardboard, 49.5 x 35.5 cm, The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham, 63.3, SC VII-173

28. Landscape – House on the Left, 1900, oil on board, 50.8 x 41.6 cm, Tate, London, N04612, Purchased 1931, SC VII-91

29. The Blue Inkstand on the Mantelshelf, c. 1900, oil on brown paper laid on panel, 33.5 x 41 cm, Norfolk Museums Service (Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery), NWHCM:1997.712, SC VII-262

30. Marcelle Aron Seated in the Conservatory at Ormesson, 1902, oil on card-

board, 38 x 57 cm, Private collection, courtesy of PIANO NOBILE, Robert Travers (Works of Art) Ltd, SC VII-380

31. The Open Window, c. 1902–3, reworked in 1915, oil on millboard, 56.9 x 45 cm, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, GMA 293, Presented by Sir Alexander Maitland in memory of his wife Rosalind, 1960, SC VII-164

32. Madame Hessel on a Sofa, c. 1905, oil on cardboard, 54.6 x 54.6 cm, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, 6217, Purchased by the Walker Art Gallery in 1964, SC VII-346

33. Stoneware Vase and Flowers, 1907, oil on paper laid down on wood, 77.5 x 54 cm, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, 2417, SC VII-501

34. In Brittany, Saint-Jacut, 1909, glue-based distemper on paper mounted on canvas, 40.5 x 50.5 cm, Private collection c/o Browse & Darby, SC VIII-327

35. The Entrance Hall, Saint-Jacut, 1909, glue-based distemper on paper, mounted on canvas, 45 x 50 cm, Private collection, SC VIII-273

36. Woman Reading in the Reeds, Saint-Jacut-de-la-Mer, 1909, distemper on paper laid down on a stretcher, 44.5 x 64.6 cm, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, PD.11-1967, SC VIII-350

37. Child in a White Smock, 1910, distemper on paper laid on to canvas, 62.5 x 68.5 cm, Private collection, SC VIII-366