Yes to life. Yes to love. Yes to generosity.

But man is also a no. No to scorn of man. No to degradation of man. No to exploitation of man. No to the butchery of what is most human in man: freedom.

Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, 1952 1

Yes to life. Yes to love. Yes to generosity.

But man is also a no. No to scorn of man. No to degradation of man. No to exploitation of man. No to the butchery of what is most human in man: freedom.

Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, 1952 1

Catherine de Zegher *

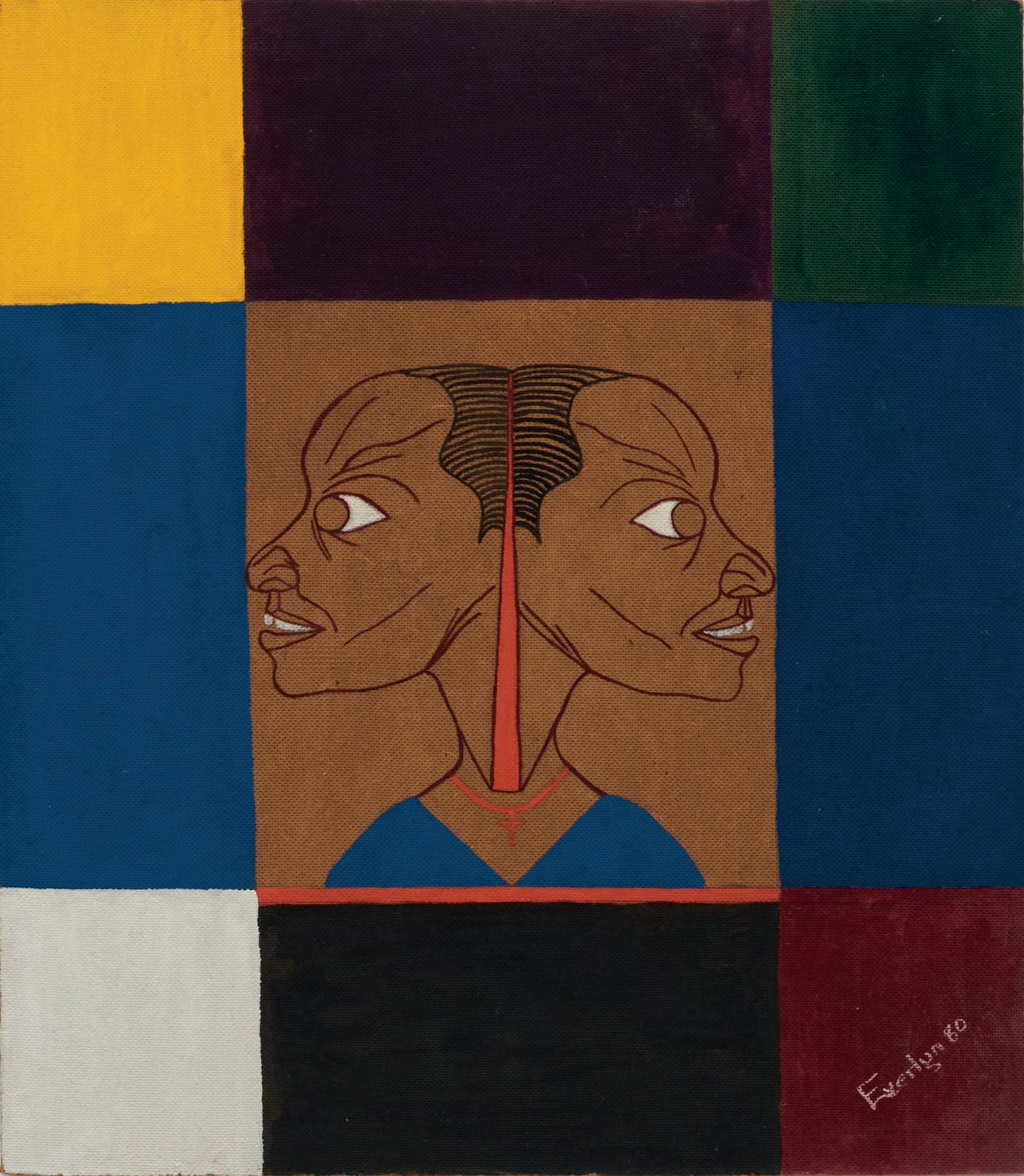

* To my children Samuel, Eva and Marga De Jaegere. Detail of The Omnipresent One, 1986 (cat.24)

Her name, her art, her writing, her whole being signify a fascinating but distressing saga of grief, hardship and trauma, both personal trauma and Black cultural trauma, as she defines it, but it is also a saga of persistence and survival. As though within her name her destiny was set to become a victorious artist and writer of and for the people. Indeed, what’s in a name? Everlyn is an Aramaic name, from the language of Jesus, meaning ‘Gift of God’ or ‘Given by God’ or ‘Wished-for child’; and Nicodemus, from the Greek nikè (victory) and demos (people), is a biblical name mentioned in John’s Gospel as the Pharisee who attempted to defend Jesus by reminding his colleagues in the Sanhedrin that ‘the law requires that a person be heard before being judged’ (John 7:50–51) – a statement that resonates throughout Nicodemus’s work.

Everlyn was the only child in the family to be given the middle name Nicodemus:

‘I guess my father had secret wishes of Everlyn being born a boy … Otherwise, why give me a name so close to his own?

My father’s Christian name was Nicodemo. We were very close, so close that my siblings still accuse me of getting all the love from our dad. He put the love of books in me and encouraged me to get educated; to never think boys were cleverer than girls; to speak my mind whatever the punishments; to think freely and not conform. He died when I was 15 years old. And that void is still with me …’2

And as the tribal society was patriarchal, of course, the fathers wanted male heirs since only males had the right to inherit. Perhaps here lie the roots of Everlyn’s feminist thinking …

In one of her essays, Everlyn Nicodemus writes that the Christian Chaggas upon the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro, where she was born in Marangu, Tanzania, in 1954, converted rather early and took their Christianity literally. And she quotes a German journalist, who wrote, ‘If you want to know how German Lutherans perform their religious duties, you should visit Kilimanjaro Lutherans.’ In Tanzania, while maybe only the Christians will know that the name Nicodemus comes from the Bible, nonetheless many people gave biblical names to their offspring, particularly in her father’s generation. It was the custom to keep the tribe’s name but to choose biblical names as first names: the Christian identity and tribal identity side by side. Next to the school tasks and the tribal work ethics, Nicodemus strictly had to fulfil her bible studies (the Old and New Testament) at church and in the choir as required for a Lutheran to receive the second baptism. ‘Know your scriptures … it was academically precise!’ she told me,