First published and distributed in 2025 by River Books Press Ltd.

396/1 Maharaj Road, Phraborommaharajawang, Bangkok 10200 Thailand

Tel: (66) 2 225-0139, 2 225-9574

Email: order@riverbooksbk.com

www.riverbooksbk.com @riverbooks riverbooksbk Riverbooksbk

Copyright collective work © River Books, 2025

Copyright text © Joe Freeman and Aung Naing Soe

Copyright photographs © Aung Naing Soe, except where otherwise indicated.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Publisher: Narisa Chakrabongse

Editor: Narisa Chakrabongse

Design: Ruetairat Nanta

ISBN 978 616 451 092 0

Cover: xxx

Publisher: River Books Press Ltd., Bangkok, Thailand

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe Oü, 16879218 - Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia, gpsr.requests@easproject.com

Printed and bound in Thailand by Parbpim Co., Ltd

CONTENTS

Part 1 – Metamorphosis

Chapter 1 – The Last Dream

Chapter 2 – A Town Different From its Name

Chapter 3 – Image

Chapter 4 – Three-Finger Salute

Chapter 5 – Sunflower Trauma

Part 2 – Damn Strong Monywa

Chapter 6 – Are the Trees Greener Outside?

Chapter 7 – Po Maung is Coming

Chapter 8 – People’s Will

Chapter 9 – A Deserter Goes to War

Part 3 – Lay Kay Kaw Paris

Chapter 10 – The River of T-Shirts

Chapter 11 – What Have You Left?

Chapter 12 – Look at the Zoo

Introduction

The golden-yellow light of the bonfire illuminated their faces. In the jungle night, all the rest was darkness. It was a cold January evening and the group of young recruits huddled close to the comforting flames. The war was quiet now. The recruits were thinking of home. They missed their families. Someone plucked the strings of a guitar and sang a famous ballad about mothers. After a few verses, others chimed in, reciting lines from one of Myanmar’s most well-known poets, Maung Chaw Nwe.

I terribly miss the color of mom’s eyes

Barely audible sobs melted into the quiet night. Maung Saungkha, the Burmese poet and commander of these soldiers-to-be, stood up from the bamboo table where he was working. He wanted to lighten the mood. He told a few jokes as his bodyguards, named Eh Wine and Van Damme – who bore more than a passing resemblance to the action star – stood by with AK-47s. Then he did something not typically associated with military life. "I will read a love poem for you guys,” he announced. It was one he had written, one they all knew. The poem is called “Mama”, but it’s not about mothers. It’s about trying to play it cool when you’re in love with someone who is more experienced and mature.

I have to light my cigarette quickly.

As if nothing happens, when I meet Mama.

Throughout history, poets have been drawn to war. Homer chronicled the exploits of Greeks who landed at Troy and those who tried to defend it. Walt Whitman volunteered to work in a hospital in the American Civil War, producing

a volume of poems inspired by his experiences. And Lord Byron established a “Byron Brigade” to fight for the Greeks during their war of independence from the Ottoman Empire. The results have been varying, from patriotic to melodramatic to anti-war, as in Wilfred Owen’s bitterly ironic lines “dulce et decorum est pro patria mori” – it is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country – lifted from Horace to offer a morbid commentary on the trenches of World War I.

Maung Saungkha is also part of this history. But what sets Myanmar poets apart is the long-standing role they have played in political upheaval and resistance. This book is about people like him, and the history that gave rise to their existence. In Myanmar, Saungkha is not an exception. In Myanmar, poets aren’t just poets. They have been on the front lines of politics, pressing for democratic reforms in Myanmar’s parliament, they have been on the front lines of protests rallying for change, and they have been on the front lines of mass displacements and refugee crises. At every major turn in Myanmar’s contemporary history, they are there. Since the February 1, 2021 coup in Myanmar, they have joined the nationwide resistance against the military, which ended a brief period of democracy by seizing power.

This book is also about why poetry still matters in Myanmar, even as it fades into obscurity, irrelevance, or Instagram banality in the west. That the nostalgic,

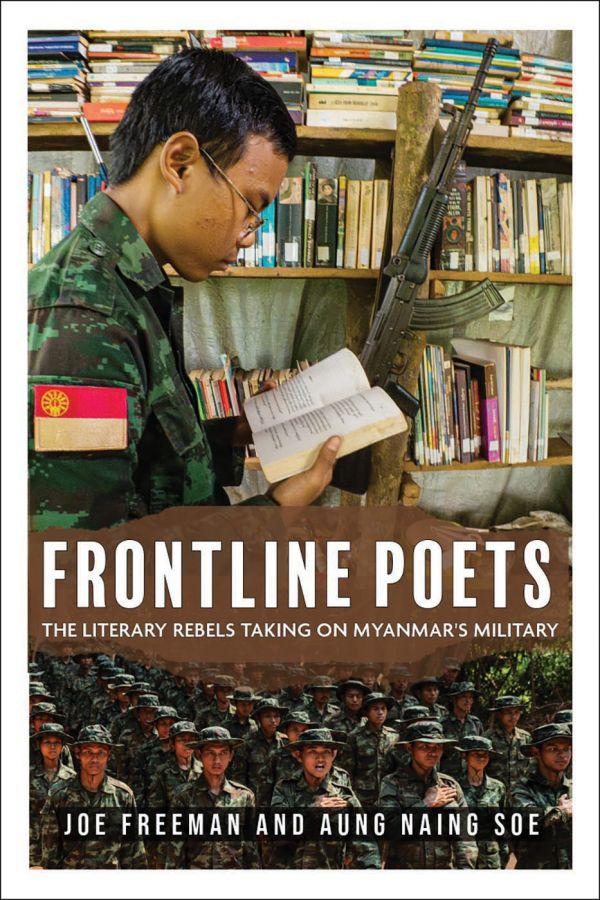

Maung Saungkha reading poems to fellow recruits (Jan 2024)

mournful love poems of someone like Saungkha found their way into a nighttime gathering of a newly formed armed group in Myanmar is no accident of history. Through their words and actions, Myanmar’s poets are again on the front lines of a historic revolutionary movement. They are risking it all to join a fight for democracy, human rights, and the soul of a country.

Percy Bysshe Shelley once called poets the unacknowledged legislators of the world. In Myanmar they are the unacknowledged historians, rebels and resistance leaders. W.H. Auden once said that poetry makes nothing happen. In Myanmar, it helped end colonialism and stirred up support for pro-democracy causes. The story of Myanmar can be told through its poems and poets. But it is not just their words. The writers themselves have been active participants. “To be a poet in Burma is more than being just a poet,” said Myanmar poet Ko Than Htun, using the country’s older name. 1 “There are many obstacles and struggles. Burmese poetry can’t escape from the reality of daily lives and settle somewhere.”

We, the authors of this book, first started talking about the outsized role of poetry in the country when we met as journalists in 2015. It was just ahead of historic elections that were supposed to catapult the country out of six decades of military rule. Since then, we have worked on countless stories together, traveled all over the country by bus, air, and boat, and met writers, politicians, historians, monks, dissidents, artists, taxi drivers, food vendors, and booksellers.

But it was the poets we kept returning to in conversations about Myanmar’s history, its literature, and its culture. When the coup occurred in 2021, Myanmar’s poets made headlines for their participation in efforts to roll it back, but the news quickly moved on. We wanted to examine what had led poets

1 Myanmar’s military changed the country’s name from Burma to Myanmar in 1989, a decision that affected many place names, with Rangoon becoming Yangon and so forth. Most governments now use Myanmar, but older generations often stick with Burma, which also tends to be favored by pro-democracy groups as a way of expressing dissent against the military in general. The change to Myanmar was heralded as being more inclusive to many ethnic groups, as Burmese reflects the dominant Bamar majority. But according to linguists the two words Myanmar and Burma are more or less the same, and the change reflects only a political decision. In this book, Myanmar will be used to refer to the country – unless it is called Burma by someone in an interview – and Burmese will refer to the official language or ethnicity.

to this point, what had happened afterwards, and learn more about how the coup had affected them and their poetry. We wanted to give a fuller picture of the frontline poets.

In this book we focus on five poets whose lives were all upended in different ways on February 1, 2021. The morning of the coup, the military arrested civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi, putting her back under house arrest less than 15 years after she was freed and allowed to participate in politics again. Myanmar’s poets responded in different ways, but those that appear in this book used poetry as fuel for resistance, both for themselves and as a tool to inspire others. They went to where the action was. Some survived. Some did not. Some are still there.

Their stories cover similar time periods in the lead-up to and aftermath of the coup, but provide different perspectives of overlapping events. In full they create a kaleidoscopic, Rashomon-like view of a dramatic, extraordinary period of turbulence that is still unfolding.

The book is split into three sections. The first delves into the life of the poet-turned-fighter Maung Saungkha, whom we first met in 2015. Having protested against war before the coup, Saungkha felt compelled to form his own armed group, the Bamar People’s Liberation Army (BPLA), after the violent crackdown that followed the takeover. In BPLA’s jungle camp, military training coexists with nighttime poetry readings and visits to a makeshift library. This section charts his journey from young, promising artist to emerging activist and rebel group leader. It includes reporting that we did back in 2016, when Saungkha was on trial for defaming Myanmar’s president with a salaciously satirical poem.

The second section moves to central Myanmar, where a robust tradition of poetry and dissent existed before the coup. We focus on two poets from the city of Monywa whose lives became linked, the fate of one influencing the decisions of another. The first, K Za Win, was a top student and monk before turning to poetry and high-profile activism. He was killed by security forces during a large demonstration in Monywa on March 3, 2021, a death that shocked Myanmar’s poetry community but also motivated them. The second person in this section, poet and environmentalist Yoe Aunt Min, was in the streets of Monywa the day that K Za Win was killed. The murder of someone she looked

up to, and the drift towards armed struggle that was occuring in Myanmar at the time, prompted her to leave Monywa and head to eastern Myanmar. There, she joined Saungkha and became a political officer in the BPLA.

The final section looks at the experiences of two poets whose paths crossed in ways they couldn’t have predicted. A Mon and Lynn Khar never became soldiers, but they attended protests and tried to contribute to the revolution in what ways they could. But they became victims of war. They barely survived military attacks, joined the exodus of refugees to Thailand, and are trying to rebuild their lives while processing the traumatic events they lived through.

This book is not meant to romanticize war or endorse the decisions of those in it. In an ideal world, frontline poets would not exist. But Myanmar right now is not an ideal world, and we believe it is important to highlight the immense sacrifices that people have made in their struggle against authoritarianism. While we have focused on poets, the number of people who have given up the comforts of civilian life to join this fight is staggering to consider, and is unprecedented in Myanmar’s modern history. There are many more stories to be told alongside this one.

We should add that this book is a work of independent journalism, for which the authors are solely responsible. The views expressed in it belong to the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect our own. It is also not a work of scholarship. As such, it is not meant to be a comprehensive overview of key poets or a who’s who of poetry in Myanmar, which has a rich, diverse, and complex history, one that could fulfill an entire research career, many PhDs, and several anthologies. These caveats aside, we hope this book opens the door to those unfamiliar with this treasure-house of a legacy, while also shedding light on the poets themselves.

It is difficult to write a book about Burmese poetry and its relevance to contemporary times without first looking to the past and explaining what, and who, came before. Poetry has been a prominent feature of the Burmese cultural landscape for hundreds of years, nourished and watered to bloom in the royal courts of different dynasties. For a long time it remained there, rarely departing from royal or religious topics in the form of stories about Buddha’s life, princely annals, or the pre-modern Burmese equivalent of nursery rhymes.2 Most of it was written by monks and courtiers. One of the earliest examples, “The Cradle

Song of the Princess of Arakan”, dates to 1455.3 In the 16th century, Burma’s wars with what was then Siam brought them into contact with Thai romantic poetry and led to the embrace of yadu, or the seasons, meditative reflections on the passage of time and nature.4

As the sonnet was in its infancy in Europe, Myanmar developed its own structure known as lei-lon tabaik, or “four words one foot.” The intricate but beautifully sensible pattern resembles a staircase descending from right to left. It demands four syllables per line, with the fourth syllable of the first line rhyming with the third syllable of the next line and so on.

After a series of violent Anglo-Burmese wars, the final British takeover in 1885 deposed Myanmar’s royal family. The British took over King Thibaw’s palace in Mandalay and packed him and his family off to India. He never returned, and was Myanmar’s last king. The ouster made an orphan of Burmese poetry, putting an end to traditions of courtly verse that had thrived in gilded palaces. Through war, exploitation, persecution, national humiliation, and diminishment, the British can be credited indirectly with making poetry political in Burma.

It’s difficult to imagine poetry without pain, longing, and melancholy. But it is also an act of memory and resistance, a refusal to accept the oblivion awaiting us. This explains the ongoing attachment to poems like John Donne’s sonnet “Death, Be Not Proud”. It is why the “Iliad” has survived millenia. The very act of writing or reciting poetry is a form of civil disobedience against the ultimate tyrant, mortality. It is also a way of recording histories that live on longer than the actual events, making their way into myth.

After Mandalay fell to the British, Burmese poetry needed a new home. The imposition of British colonial education brought with it access to stories, styles,

2 Ko Ko Thett, “From Panegyrics to the End of Poetry.” Poetry International, November 29, 2011. www.poetryinternational.com/en/poets-poems/article/104-21270_Frompanegyrics-to-the-end-of-poetry

3 Ko Ko Thett and James Byrne, Bones Will Crow. Cornell University Press, 2013

4 Maung Htin Aung, José Maceda, John B. Glass, James R. Brandon, and Philip S. Rawson. “Southeast Asian Arts | Music, Dance, & Visual Arts.” Encyclopedia Britannica, July 26, 1999. www.britannica.com/art/Southeast-Asian-arts/Literature

and works from across the globe. Interestingly, while poetry would be used to express dissent against the British, Burmese writers also grabbed what they could from the new works available to them in a clever, reverse form of literary appropriation. In 1904, the Burmese writer James Hla Kyaw published Maung Yin Maung, Ma Me Ma, a Burmese adaptation of Alexandre Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo. It was considered the first Burmese novel. In the words of the writer Min Zin, “it was an epoch-making work in the history of Burmese literature. This innovation led others to realize that exposure to world literatures, particularly those of the West, would greatly assist efforts to modernize Burmese literary writing.”5

Dumas’s imprisoned, vengeful hero Edmond Dantes was not the only character to find new life in the pages of Burmese books. Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes inspired writer Shwe U Daung to create a Burmese detective named Maung San Shar, who was modeled on the Baker Street sleuth and whose exploits in colonial-era Rangoon closely followed his literary predecessor. Shwe U Daung even kills off his hero by having him plunge to his death from a waterfall, as Doyle did with Holmes once he tired of the character.6

While these books were popular, they may give an inaccurate sense of how welcome British ideas were in Burma, which simmered with anti-colonial sentiment. As the push for independence grew, emerging resistance leaders founded the nationalist Dobamar Asiayon, or We Burmans Association. Their members appended thakin, or master, to the front of their names to thumb their noses at the British and express self-determination. The thakins went on to lead the country, including U Nu, the country’s first prime minister, and Aung San, the leader of the Burmese Independence Army and the father of Aung San Suu Kyi. Aung San was assassinated in 1947 in what historians believe was a power struggle.

But one of the most famous thakins was a poet. Born in 1876, U Lun started out as a journalist, expanding to drama, satire, and poetry to skewer British colonial authorities. He became Thakin Kodaw Hmaing, an extension of a previous pen name.7 One of his more memorable poems was an endorsement of a boycott on British goods. “His odes extolled the glories of Burma’s great past and exhorted his countrymen to throw off the foreign yoke,” wrote author U On Pe in a 1958 supplement of The Atlantic. “The varying moods of U Lun's

poetry are those of a nation going through the painful, slow ordeal of rebirth. From month to month, he recorded the struggle and stirred us to further effort.”8

He blazed a path for how poets would interact with successive regimes. They would not shy away from politics, but would confront it, play with it, shake it around, leave it spinning and dizzy. “Thakin Kodaw Hmaing was the first revolutionary poet, and his works are very much related to leftist, communist ideas,” said contemporary Myanmar poet San Nyein Oo, describing him as the “number one enemy of the British” during the colonial period. “His poems are up to date. He used poetry and literature as a weapon for the revolution. It has new forms and new concepts including politics.”

San Nyein Oo said that British colonial education had imported romantics like William Wordsworth, whose effulgences about nature, seasons, and flowers were seen as safe subjects to teach. “That’s why the British government taught William Wordsworth. They want to put Burmese people in their system,” he said.

With the founding of the University of Rangoon in 1920, Myanmar poetry settled in a new home. Influenced by romantic poets, the khitsan, or “testing the times,” movement took shape. Poets Zawgyi and Min Thu Wun emerged as its forerunners (we will come back to them in more detail later). They took the emotionally charged and nature-imbued verses of Keats and Wordsworth and plonked them down in a Burmese setting. Zawgyi wrote a series of lyrical, melancholy poems about hyacinths. Min Thu Won placed his poems in villages, forgotten battlefields, and among scenes of rural poverty and despair. In the poem “My Husband Since Our Young Days,” 9 Min Thu Wun describes a rural tragedy amid the harshness of agrarian life:

5 Min Zin, “The Living History: Dagon Taya and Modern Myanmar Literature.” The Irrawaddy, May 10, 2019. www.irrawaddy.com/from-the-archive/living-history-dagontaya-modern-myanmar-literature.html

6 Oliver Slow, “The Burmese Sherlock Holmes.” Frontier Myanmar, May 3, 2016. www. frontiermyanmar.net/en/the-burmese-sherlock-holmes/

7 Thakin Kodaw Hmaing (1876-1964), The Irrawaddy, March 2000, Volume 8 No. 3. www2.irrawaddy.com/article.php?art_id=1836

8 U On Pe. Modern Burmese Literature. The Atlantic, February 1, 1958. www. theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1958/02/modern-burmese-literature/306830/

9 As seen in the 1978 The Myawaddy Press anthology translated by U Win Pe

1 | The Last Dream

The poet wanted to see John Wick 4 .

“I haven’t been to the movies in two years,” Maung Saungkha said. He was sitting in the back seat of a car driving along a street in Thailand. The windows were tinted, throwing a gray hue over the passing scenes of civilian life. The scenes were peaceful ones. Shopping, lazy traffic snarls, the commercial hum of a mall. It was a stark contrast to his new home base in the jungle over the border in Myanmar, where young people from civilian backgrounds were being trained in the art of war. He was helping train them.

The passengers looked out the window. In Thailand, it was the season for crop burning. Haze filled the air, giving it the cloudy aura of a dirty aquarium. The car passed a nightlife spot popular with Myanmar exiles. A fleeting reminder of the social life Saungkha had left behind. Another era. Nights out with friends at tea shops. Drinking beer and whiskey, smoking cigarettes, dating, dancing, protests, and romance. Poetry readings at bookstores. The life of a 20-something writer in a big city. But if Saungkha noticed he did not comment. There was no nostalgic sigh. Home wasn’t the same any more. Home was gone.

In the space of three years, this former human rights activist and poet, who had founded a freedom of expression NGO and gone to jail for publishing subversive lines on Facebook, had transformed himself into the leader of an armed group, the Bamar People’s Liberation Army, or BPLA. Its enemy was the Myanmar military that had seized power in the 2021 coup. Like others, he had given up on peaceful protests and embraced armed struggle. This was no part-time adventure. Except for these forays into civilian life to rest, recuperate, and meet old friends, Saungkha was a rebel who lived in the jungle. He wore fatigues. He gave orders. He buried comrades. This former poster child for PEN Myanmar now knew how to fire an automatic weapon.

He had been on the front lines, but his former self lived on. He was lean but not mean. He had not lost his smile, his laugh, or his ability to tell a joke. In his

heart, he was still a poet. But in the metamorphosis from writer to fighter, did one replace the other, or did both selves coexist? When poets acknowledge that the sword may be mightier than the pen, what happens to them? He had been thinking about this. “Armed revolution is very difficult for me as a poet and human rights defender,” he said. He was now sitting down on a comfy sofa, in a quiet house, polishing off a lunch of Burmese nan gyi thoke noodles. “I am sure that I don’t like being a soldier. That’s not my life. I am here because the political system pushed me here. I am holding arms because I am unfortunate. I am not happy with that.”

He became a soldier because of the revolution, he added. But he would get back to his calling one day. “After this, I will write poems again, or something else, or maybe become a politician. But I won’t continue holding arms. I am sure that I will get my life back,” he said. “I still have humanity and respect for human rights standards in my mind the entire time. That will never vanish.”

He was writing when he could find the time. The plan was to release a book to raise funds for the resistance. But it was difficult. “It's been a while since I’ve been able to spend time on poetry. I had to focus a lot on the army, not the poems,” he said. “But it doesn’t mean that I am letting the poetry go away from me. Poems are always in my mind.”

He took out his phone and read some verses he had written in the jungle. The poem was about two comrades who had been shot and killed, but really it was about how young people were dying in this fight while for most, life went on as normal. Many people their age in Myanmar didn’t care. They went out to nightclubs and had fun. They were living in what Saungkha called “the other world,” where no one feels sorrow for the fallen. “Some young people don’t even know about that kind of event,” he said. So he wrote a poem about it that incorporated elements of a Myanmar song called “The Last Dream,” which he had sung to himself in prison to lift his spirits. That song had been written by a poet in the 1970s, who had composed it in honor of students killed during a protest crackdown. Saungkha titled his homage to his comrades “My Eyes, Still Wet With Tears.”

The frivolous parties grew louder, While the world, in tears, felt smaller. "Be strong,"

We comforted, clinging to each other as we fell apart.

The soldier conveyed his despair with silent gestures.

His head, severed and left behind—

We found it only later.

The green leaves keep falling...

The opening lyrics of The Last Dream are about the young, gone too soon.

And yes,

Some can still look away.

Saungkha worried that the longer the revolution went on, the more people would join this other world of nightclubs and “frivolous parties.” The poem is against apathy, indifference, and silence in the face of grave injustice. But the crucial line is about falling leaves. Green leaves should not fall, just as young people in the prime of their lives should not be killed fighting a war.

Despite his new role, Saungkha still did not look like a soldier. His hair was close-cropped, but it had always been. And while he had lost weight trekking through the jungle and barely drank or smoked any more, he had never been heavy or much of a party animal. Despite being in his early 30s and having more life experience than most men his age, his wide smile and easy demeanor gave him the air of a bleary-eyed graduate student, his head buried in books, not tactical manuals. It was easy to briefly forget that he was the commander of an armed group, that he was risking his life, that he was wanted by the Myanmar junta. At this stage of the coup, the junta had executed four regime opponents, tortured countless others, killed more than 4,000 civilians, and thrown more than 20,000 people into its fetid jails across the country.

The struggle was his life now. But even rebels need to see the occasional movie.

That night, he and his girlfriend joined a group of Myanmar exiles to watch Keanu Reeves dish out vengeance to a slew of bad guys. The couple wore black sunglasses and face masks, an innocuous disguise in a country where people still widely masked up due to pollution and the stubbornly persistent coronavirus. John Wick 4 is almost three hours long, and there were no Burmese subtitles, only Thai. But in a movie where the dialogue was a secondary consideration at

best, it wasn’t hard to follow. Scene after scene featured stabbing, bludgeoning, and the titular hero shooting villain after villain in the head.

The fictionalized violence on screen should have been triggering for viewers who had come from the actual front lines or who knew people affected by the coup. But everybody seemed to love it. They staggered out of the theater past 1am, the mood one of joyful fatigue. Perhaps the movie didn’t matter. It was more about the sensation of doing something normal, going to a film with friends, drinking Coke, sharing popcorn, laughing at the absurd, over-the-top violence. Wars of liberation are often fought over high-minded ideals – big words like democracy, human rights, and justice. But in the end, they are also fought for the idle, humdrum freedoms we all take for granted – the freedom to watch a B-movie with your friends, go home without fear of arrest, and sleep in peace in your bed.

To understand Saungkha’s trajectory, it is useful to take a snapshot of Myanmar’s turbulent modern history. The military, known officially as the Tatmadaw, or Royal Fighting Force, has been a constant and overwhelming presence in the lives of tens of millions of people. It controls the economy, with interests in mining, real estate, banking, and telecommunications. It controls the media, with military-aligned newspapers and television stations permitted to flourish even as independent journalists face lawsuits, jail time or operating bans. And it controls the country’s politics, using a constitution it drafted to fill 25 percent of seats in parliament with soldier MPs, effectively allowing it to block any real change.

One of two vice-presidential positions is reserved for a military candidate, and the military controls the Defense, Home and Border Affairs ministries. Almost every generation since independence has experienced a military coup, mass protest movements, economic instability, violent crackdowns, and religious tensions between the Buddhist majority and Muslim minority. The words “Burmese” and “Burma” linguistically reflect the country’s dominant ethnic group, the Bamar. The vast majority of the country’s military and political leaders since independence in 1948 have been Bamar Buddhists. Saungkha is Bamar. But by creating the Bamar People’s Liberation Army, he flipped the idea of the Bamar as oppressors on its head.

In a country that is a mish-mash of defunct kingdoms, the terms “Burma”

and “Myanmar” sound misleadingly monolithic. There are dozens of ethnic groups living in states that have strong cultural, religious, linguistic, and historical identities that do not align with the Bamar Buddhist outlook. There are sizable Christian and Muslim populations – roughly six and four percent of the population, respectively. As they did elsewhere, British colonial administrators hardened existing divisions by drawing up official lists of ethnic groups, ranking them, and placing them within power hierarchies. In the 1920s and 30s, they also permitted immigration from India for labor, stoking religious tensions within Yangon. There were anti-Chinese, anti-Indian, and anti-Muslim riots in the city, a cycle that continued into the 21st century. This is hard to grasp for visitors to Yangon, who see temples, mosques, churches, and even a synagogue sitting cheek by jowl on the British-built grid of long streets downtown. But as is the case in most countries, scratch the surface and you’ll find historical tensions simmering underneath.

Those tensions bubbled up and spilled over at the exact time Myanmar was supposed to be changing forever. If the transition to democracy led by former generals in 2011 seemed too good to be true, that’s because it was. But who could resist the narrative at the time? Nobel Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi was out of house arrest, winning elections, and going on a victory lap in the West with her high-profile supporters.

Tourists poured in. Hotels sprang up. Decades of isolation ended. Official censorship of newspapers was lifted, Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton paid high-profile visits, sanctions were dropped. People embraced smartphones and internet use exploded. There was the symbolic arrival of Western companies like Ford and KFC – there were lines outside on the first day. The country was awash in the fanfare of free and fair elections and its first census in decades. This euphoria of new beginnings muted a dissonant soundtrack that was playing in the background the entire time, but that few wanted to hear.

But Saungkha was listening.