Jacques Grange

Gay Gassmann

Pierre Passebon

Diane de Polignac

Gay Gassmann

Gay Gassmann

Gay Gassmann

Julie Goy

Sommaire | Table of contents

I. Préface Foreword

II. Introduction

III. Rouge, la couleur. Rougemont, les couleurs Red, a color. Rougemont, many colors

IV. L’élégance du cœur et de l’esprit Elegant in heart and mind

V. L’artiste dans le Sud et à Paris

The artist in the South of France and Paris

VI. 60 ans d’art et de création

60 years of Art and Creation

VII. Vivre avec l’art de Guy de Rougemont

Living with the art of Guy de Rougemont

VIII. Sculpter dans l’espace public

Creating for public spaces

Liste des réalisations toujours visibles dans l’espace public

List of installations still visible in public spaces

Julio Le Parc

Hervé Lemoine

Adrien Goetz

Annexes

IX. Rougemont

X. Rougemont au Mobilier national Rougemont at the Mobilier national

XI. Rougemont, un académicien qui n’avait rien d’académique Rougemont, a non-academic academician

XII. Biographie sélective | Selective biography

XIII. Bibliographie sélective | Selective bibliography

XIV. Index

XV. Crédits | Credits

XVI. Remerciements | Acknowledgements

II. Introduction

Table nuage | Acier inoxydable et plexiglas | Cloud Table | Stainless steel and plexiglass

Pour l’historienne de l’art que je suis, ayant suivi une formation académique et m’étant spécialisée dans les arts décoratifs, les deux mondes des beaux-arts et des arts décoratifs ont toujours cohabité sans heurt dans mon esprit et dans mon travail. Le clivage apparent entre les arts majeurs de la peinture et de la sculpture, d’un côté, et les « arts mineurs » qui comprennent le mobilier, la céramique, la verrerie et la ferronnerie, de l’autre, a toujours été clairement marqué. Il y a les artistes, et il y a les artisans. Des frontières existent dans l’esprit des artistes eux-mêmes, quand elles ne leur sont pas imposées par le monde de l’art en général. Très peu d’artistes ont réussi à être à cheval sur les deux mondes, ou l’ont même souhaité. Guy de Rougemont est un oiseau rare, dans la mesure où il y est parvenu. Dans une carrière qui s’étend sur un demi-siècle, il a créé ce qu’il voulait, quand il le voulait, et par sa curiosité il a su brouiller les lignes de séparation entre le public et le privé, entre les beaux-arts et les arts décoratifs. Il passait d’œuvres en deux dimensions à des œuvres en relief, sans difficulté et de façon interchangeable. Pourtant, il s’est toujours

défini comme un peintre avant toute chose. Un jour, il m’a dit : « Je suis un peintre. Un peintre qui sculpte. Un peintre qui dessine des meubles. Un peintre qui crée. » Il n’y avait jamais ni confusion ni ambiguïté dans sa pratique. De son point de vue, du moins. Le nom de Guy de Rougemont est toujours resté connu, mais souvent sans que personne ne sache très bien qui il était, ni pourquoi ce nom leur dit quelque chose. D’une certaine façon, il est parvenu à rester sous les radars, mais ce qui a sans doute le plus contribué à son renom, c’est d’avoir dessiné ce qui deviendra la table nuage, créée à l’origine à la demande du grand décorateur français Henri Samuel, et produite en 1970. Chérie par les amateurs de design, la table est célèbre, mais pas forcément celui qui l’a dessinée. C’est l’une des raisons pour lesquelles il m’a paru nécessaire de raconter l’histoire de Rougemont, de dévoiler sa vie et son œuvre en écrivant un livre. L’homme Guy de Rougemont avait tellement de contradictions : un aristocrate français extrêmement fier de son héritage, un dandy qui évoluait à travers la scène parisienne avec aisance et

Gay Gassmann

Portrait de l’artiste | Portrait of the artist | 1979

30 thermographies | 30 thermographics | Rue

| 1979

Victor-Hugo, Lyon

Henri Samuel | Grand salon iconique | Iconic grand salon | 118, rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré, Paris | vers 1978 | circa 1978

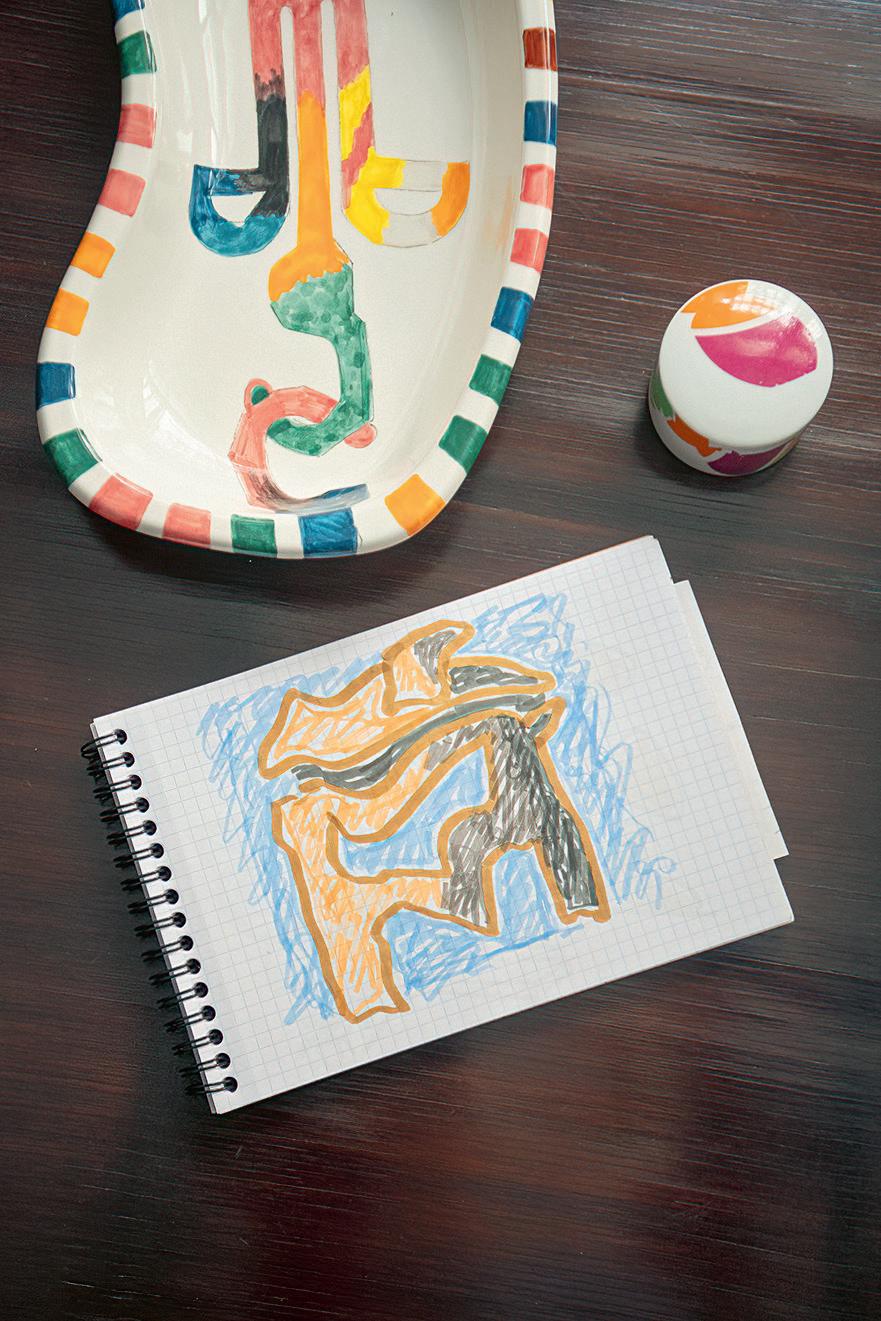

Œuvres de l’artiste | Works by the artist | Collection Pierre Passebon

Détail d’une table | Detail of a table | Collection Pierre Passebon

Fauteuil serpentine | Serpentine armchair | Aluminium | Collection Pierre Passebon

and his sense of humor charmed me at once. Afterwards, I met his wife Anne-Marie Deschodt, whose beauty and personality definitely justified the success of the highly Parisian couple they made. When I walked with Guy, I understood his ever-curious eye: for the ephemeral beauty of a ray of light on a bright orange crane against a gray sky, or for a sunset on the padlocks of the Pont des Arts, which, like an alchemist, turns the bridge into gold. I have always admired the people who show me the beauty I too often miss.

Guy’s military side (he was the son of a general) expressed itself through his love of order, his natural authority, his decision to sign “Rougemont” without a first name or aristocratic “de,” his straight columns all lined up, his colors, as honest and proud as a flag, and his taste for clubs, whether at Castel’s or at the Académie des beaux-arts. Rougemont had panache! It was Guy de Rougemont the academician who formally presented me with the insignia of the Chevalier des Arts et des

Lettres in 2010, and it was he who insisted that I be promoted to the rank of officer in 2015. I was touched by this paternal care.

In 1972, Henri Samuel commissioned Guy de Rougemont, François Arnal, Philippe Hiquily, Diego Giacometti, and César to create pieces of furniture for his house. The artists accepted the commission with enthusiasm, for Henri Samuel was an internationally renowned decorator who worked for prestigious collectors. Guy explained to me that the original design for one of the two coffee tables was never realized, as Henri found the table surface too small. That is how the Ellipse Table, with its overly deep intersections, became the Cloud Table, with softer angles. We decided to cast the table from the original design in 2001. Guy humorously kept the name “à la Lalanne.” Due to the success that ensued, three casts were made.

There were several exhibitions at the gallery, each one different from the next, but they were always complementary, following a rigorous

Behind an unassuming wooden green door, not far from the town square of Marsillargues, is the little slice of paradise which Guy de Rougemont and his wife AnneMarie Deschodt created for themselves, some 20 years ago. The creative couple loved the South of France and divided their time between Paris and this hidden hideaway full of light, color and life. When they first discovered this compound of 18th-century buildings, it really wasn’t much to look at. According to Rougemont, “This house was linked to agriculture. They stored grain here and my studio was for the sheep and there were stables. It was Anne-Marie who fell in love with this house. She was the mistress of the house.” Rougemont designed the basin in the entrance courtyard which

was an invitation to paradise. Shaded and covered in green, somewhat wild, but absolutely stunning.

Together, the couple created a real artist’s house, full of books, works of art including gifts from other artists, and mementos from family, travels and everywhere else. Rougemont said a few years ago, “This is a house of painting and writing. I am not very savant, but I am curious.” Indeed, there were books everywhere, and on the ground floor

Anne-Marie had a library and an office where, Rougemont pointed out, she read Proust and Balzac.

There were paintings and works of art everywhere, even on the ceiling, which is unusual but beautiful. On the top floor, Rougemont continued, under the roof, is

MARSILLARGUES, SOUTH OF FRANCE

Gay Gassmann

V. The artist in the South of France and Paris

V. L’artiste dans le Sud et à Paris

MARSILLARGUES, SUD DE LA FRANCE

Marsillargues | France | 2019

Gay Gassmann

Derrière une discrète porte verte en bois, non loin de la place du village de Marsillargues, se trouve le petit coin de paradis que Guy de Rougemont et sa femme, Anne-Marie Deschodt, se sont construit il y a vingt ans. Ce couple de créatifs aimait le sud de la France et ils partageaient leur temps entre Paris et cette retraite cachée, pleine de lumière, de vie et de couleur.

Lorsqu’ils le découvrent pour la première fois, cet ensemble de bâtiments du XVIIIe siècle ne paie pas de mine. D’après Rougemont, « la maison était liée à l’agriculture. On y stockait du grain, mon atelier servait aux moutons et il y avait des étables. C’est Anne-Marie qui est tombée amoureuse d’elle. C’était la maîtresse de maison ». Rougemont dessine le bassin de la cour d’entrée, une véritable invitation au paradis :

ombragée, couverte de verdure et quelque peu sauvage, mais absolument magnifique. Ensemble, le couple crée une vraie maison d’artiste, pleine de livres, d’œuvres d’art (dont certaines offertes par d’autres artistes), ainsi que de souvenirs de famille, de voyage et de partout ailleurs. Rougemont a dit il y a quelques années : « C’est une maison de peinture et d’écriture. Je ne suis pas très savant, mais je suis curieux. » En effet, elle regorge de livres dans tous les recoins, et au rez-de-chaussée Anne-Marie a une bibliothèque et un bureau où Rougemont précise qu’elle lit Proust et Balzac.

Les tableaux et les œuvres d’art pullulent, même au plafond, qui est étrange mais très beau. Au dernier étage, sous le toit, poursuit Rougemont, se trouve un rangement pour les sculptures, et aussi sa bibliothèque et son

Guy de Rougemont dans son atelier après son retour de New York | Guy de Rougemont in his studio after returning from New York | Paris | 1967

1. Comments made to the author in November 2019

The French artist known as Guy de Rougemont, born Guy du Temple de Rougemont, entered this world on April 23, 1935, in Paris, and left it at the age of 86, on August 19, 2021, in Montpellier, in his beloved South of France. Rougemont was first and foremost a painter. Although he transcended the boundaries between the fine and decorative arts, he was in his own words a painter who sculpted, designed furniture, and made all manner of things.1

After his early years in Normandy, France, at the age of 16 he and his family spent a year in Washington DC, his father General Jean-Louis du Temple de Rougemont having been appointed to the Pentagon. Upon the family’s return to France, the young Rougemont entered the Ecole nationale supérieure des art décoratifs in Paris, remaining there from 1954 until 1958, and studying under the French painter Marcel Gromaire (1892–1971), who was inspired by Cubism and new ideas of figuration. These lessons went straight to the essence of what the young artist was absorbing and distilling during his studies.

While still a student and budding artist, Rougemont participated in several collective shows, and in 1962 he received a grant to attend the Casa de Velázquez in Madrid. This institution, a French art school located in Spain, had been founded in 1920 to promote artistic, cultural and academic exchange between the two countries. Rougemont received his grant

from the City of Paris, and remained in Spain for two years, during which time he met a number of highly significant figures, including the French art historian Daniel Alcouffe, who would go on to become Conservateur général du patrimoine and Directeur du département des Objets d’art at the Louvre; Spanish literature professor Jean Canavaggio; and artists Jean Degottex, Jean Dupy and Manuel Viola. It was also during these years in Spain that he held his first solo show in that country, in 1964. The following year, 1965, Rougemont decided to head back to New York. While it has often been written that the artist spent a year in that city, it is perhaps much less well known that there he stayed with his great friends Jean and Irène Amic. Irène speaks fondly and enthusiastically about Rougemont, a close family friend: “Guy was one of the oldest friends of my husband. They had known each other since they were around 17 years old and were extremely close. There was also a time when we were probably the biggest collectors of his work. We were living in New York then, in a brownstone and had apartments we lent to friends. And then Guy came for 15 days and he stayed practically a year!” She continues, “When he was in New York we have so many stories. Once he came with Julie Christie and everyone thought she was Brigitte Bardot! He knew other artists of course like Marisol, and we knew Helen Frankenthaler at that time. In the brownstone Guy did a fresco in the garden

Gay Gassmann

VI. 60 years of art and creation

Autoroute de l’Est in France. His artistic 30 kilometers runs from Châlons-en-Champagne to Sainte-Menehould in the East of France. Rougemont embraced this ambitious commission with his usual enthusiasm and vision, creating a world comprising 154 cylinders, 60 spheres, 960 cubes and several thousand other geometric forms along the 30-kilometer stretch. The results are impressive and surprising, an unexpected “gift” for the travelers on the motorway. It is important to note that this was in 1977, yet the “artistic” 1 percent for public art to be included in all French infrastructure projects did not come into effect until the 1980s.

These 30 kilometers are visible and remarkable for all to see, but when asked who designed it, most people would be silent. The same applies to other public commissions he received throughout his career, like the Entrance Hall to the new Hôpital Saint-Louis in Paris (1985) or the Salle des Assises of the Tribunal de Bobigny (1986.)

From the motorway to the ground underfoot,

la couleur sur des surfaces urbaines horizontales3. » Ces dessins remplissent son atelier parisien et peuvent également être considérés comme les tableaux inachevés auxquels il travaillait durant les dernières années de sa vie.

Avant de poursuivre ce compte rendu de la carrière artistique de Rougemont, nous pouvons mentionner une autre commande importante qu’il reçoit dans les années 1970. En 1977, il installe le projet Environnement pour une autoroute qui court sur trente kilomètres de l’A4, dite « autoroute de l’Est ». Ses trente kilomètres artistiques vont de Châlons-enChampagne à Sainte-Menehould dans l’est de la France.

Rougemont accepte cette commande ambitieuse avec son enthousiasme et sa vision habituels et crée un monde composé de 154 cylindres, 60 sphères, 960 cubes et plusieurs milliers de formes géométriques diverses et variées le long de ces trente kilomètres. Les résultats sont impressionnants et surprenants, un « cadeau » inattendu pour les automobilistes. Notons que tout cela se

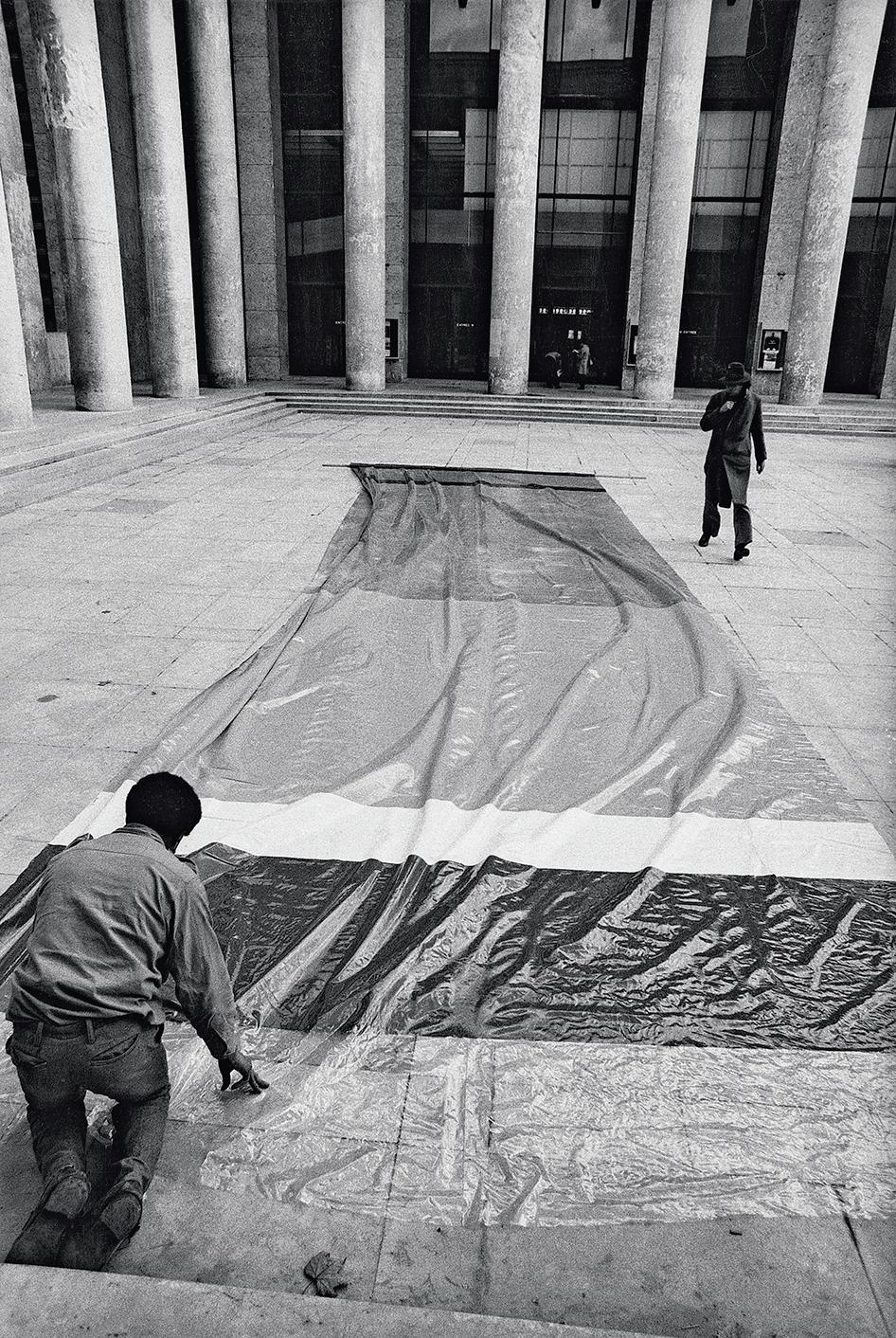

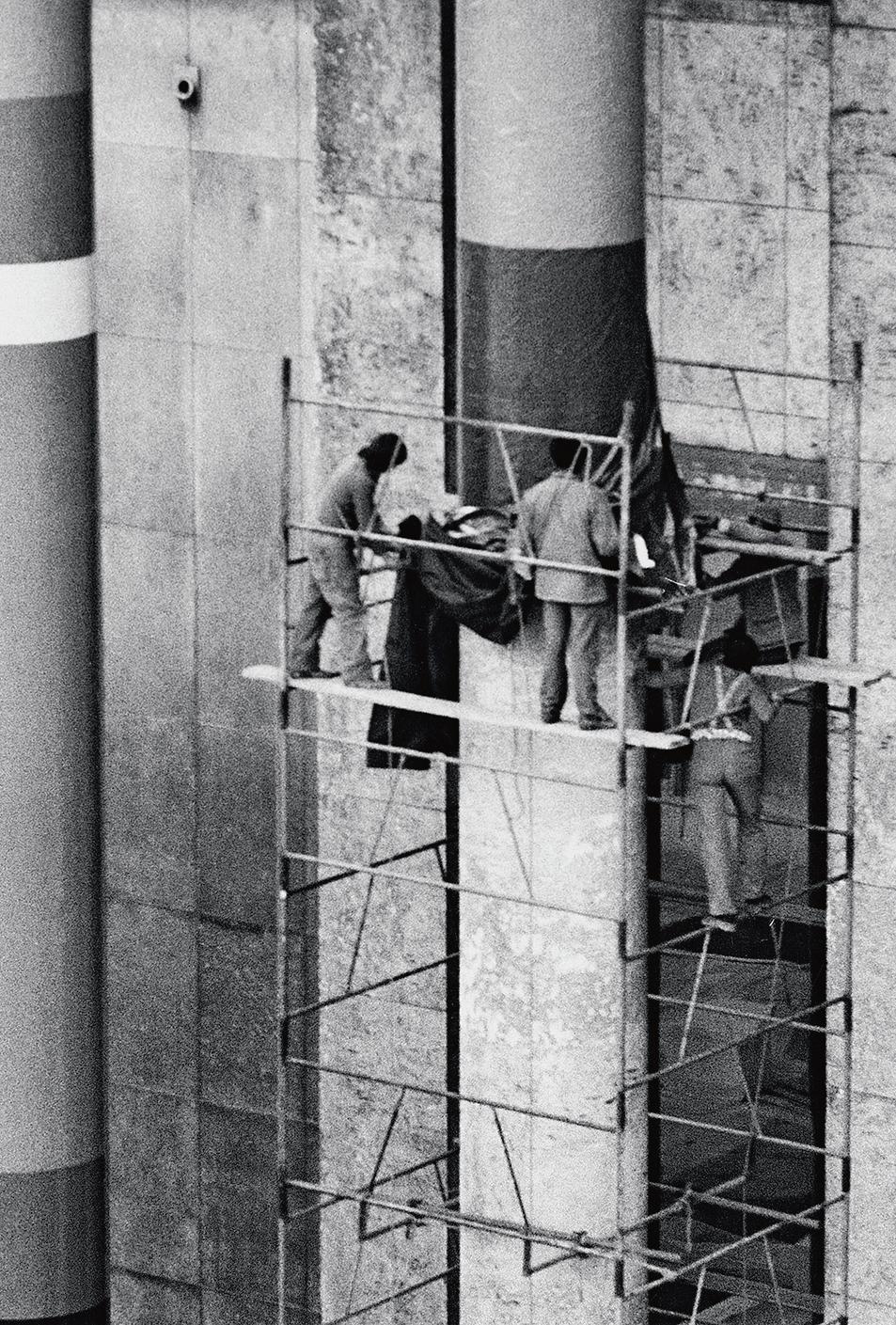

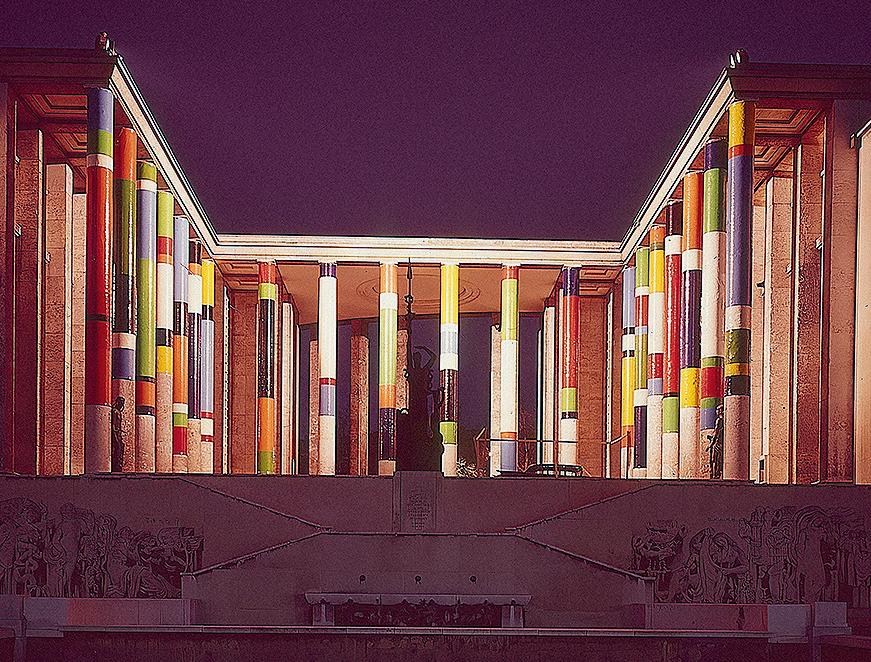

Mise en couleurs d’un musée | Musée d’Art moderne | Paris | 1974

Mise en couleurs d’un musée | Musée d’Art Moderne | Paris | 1974

Guy de Rougemont devant le Musée d’Art Moderne | Guy de Rougemont in front of the Musée d’Art Moderne | Mise en couleurs d’un musée | Paris | 1974

Intérieur | Interior | collection privée | private collection