AR+D Publishing

AR+D Publishing

1930

ALUMINAIRE HOUSE: THE MIGRATING VILLA

For most people, their social existence and cultural environment are experienced through a shared series of values, ideas, conventions, and symbols of a given era. The social imaginary is often expressed not in theoretical terms, but rather is carried in images, stories, and legends—it is a mutual understanding that enables the existence of common practices and a widely shared sense of legitimacy.1 The events that shape the social imaginary are diverse and independent for a majority of historical periods. These events rarely can be organized within a coherent system of cause and effect. On the contrary, these events frequently intermingle, creating a constellation, an atlas of images and narratives whose relations are established more because of their simultaneity than their objective links. On rare occasions, all the events of an era can be organized consistently around one unique historical phenomenon. The decade of the 1930s in the United States of America (USA) can objectively be included in this category, as all the main historical occurrences of the era gravitate around one central concept: the Great Depression.2 These years can be considered as the first period of American history to be fully documented graphically. The technological advancements in photography and cinematography made it possible to replace the previously bulky equipment with lighter, portable cameras. Alongside the simultaneous improvements in printing and publishing, new technology allowed photojournalists and documentarists to produce a lasting body of work that permitted Americans to look at themselves as never before and future generations to more extensively see the past.

The 1930s were a watershed in the story of the United States, capturing an unusually consistent and centralized social imaginary.3 The resulting imaginary of this era has enormous persistence and validity in contemporary American society due mainly to several aggregated circumstances. The decade witnessed the establishment of a new balance between government and people, public works and services , and business and labor. The government exceeded its caretaker role after the 1932 presidential elections; it took responsibility to ensure that every American would be able to earn at least the basic means of life for themselves and their families. As historian T. H. Watkins puts it, this is a “new intimacy so thoroughly in place today that it is difficult to remember that once it was a revolutionary concept.”4 Until today, many persistent legislations, federal institutions, and agencies were created during the first and second New Deals, facilitated by a more active role of government in the daily life of contemporary American population. The best example might be the Social Security Act of 1935. Moreover, the legacy of this era is not

restricted to politics and government, it manifested materially in the built public works and infrastructures. A large percentage of the New Deal irrigation systems, dams, sanitation plants, pipelines, power plants, highways, national parks, public pools, schools, hospitals, post offices, courthouses, city halls, and housing projects are still in use today.5 This era also produced a profound change in patterns of mobility and the relationship Americans established with the territory they inhabit. Although there had been large migrations prior in the United States—namely the Great Migration of African Americans leaving the South since 1910, along with westward migration after the cession of the Mexican territories at the end of the Mexican–American War in 1848—the forced migrations during the depression created the social acceptation of a more nomadic and less rooted life in the territory. Documented by the media and vivid in public memory, this transient way of life is still a very relevant component of American contemporary life.6

Paradoxically, the monolithic social imaginary of the Depression era goes hand in hand with an extraordinary cultural exuberance unexpected for a time of deep economic and social crisis. Although the cultural manifestations of the time seem to be extremely diverse, they can always relate to the central concept of the Great Depression and be classified in two main categories that occupy two ends of a spectrum: the documentary approach of those artists willing to denounce the economic hardship and social injustices, and the escapist entertainment approach that aims to alleviate the anxiety of the general public by helping them picture a more promising future. Under the first category can be classified the work of writers like John Steinbeck, Erskine Caldwell, Mike Gold, and James Agee; photographers like Walker Evans, Margaret Bourke-White, Dorothea Lange, Arthur Rothstein, Russell Lee, Carl Mydans, Ben Shahn, and Marion Post Wolcott; documentarists as Pare Lorentz; and crooners like Woody Guthrie. The paradigms of the second category are the glamorous movies produced in Hollywood during this era, but there are many other examples included in what literary historian Morris Dickstein labels as “the culture of elegance.”7

Being a useful art, architecture positioned itself in an intermediate category between these two poles immediately after the 1929 crash. It became clear that the extravagant, market-oriented Art Deco style dominant earlier in the decade was inappropriate for a moment of profound social pauperization. Luxury might be accepted in a lavish Hollywood fiction, but it was unbearable in the material realities of everyday life. Thus, the Streamline style demonstrated the design

AR+D Publishing

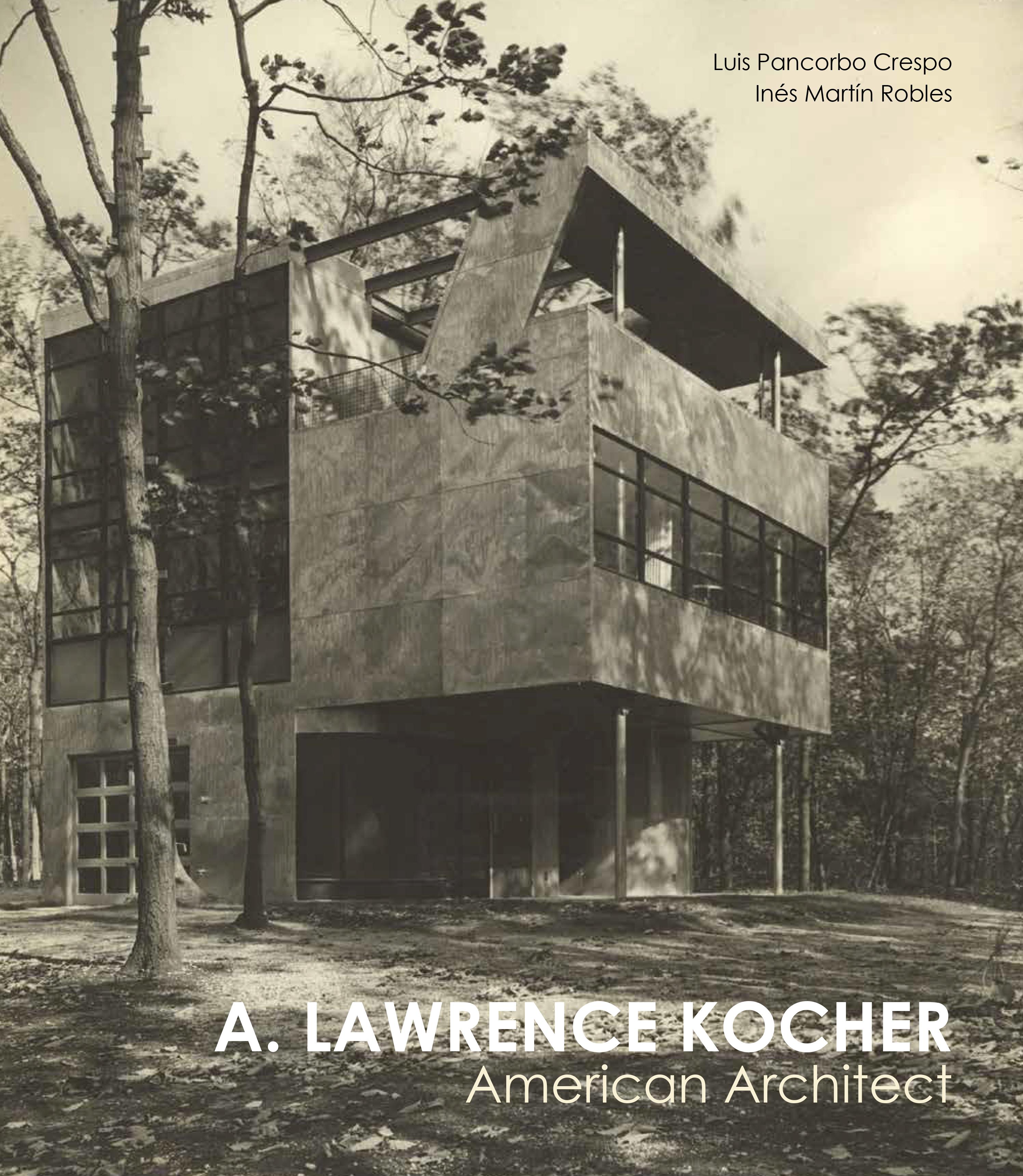

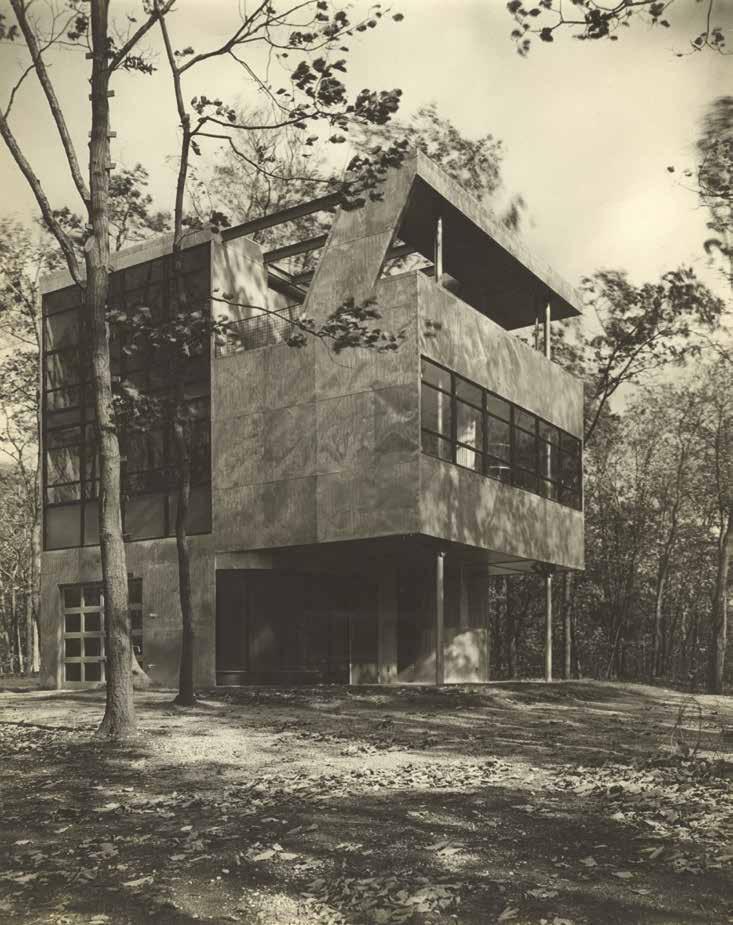

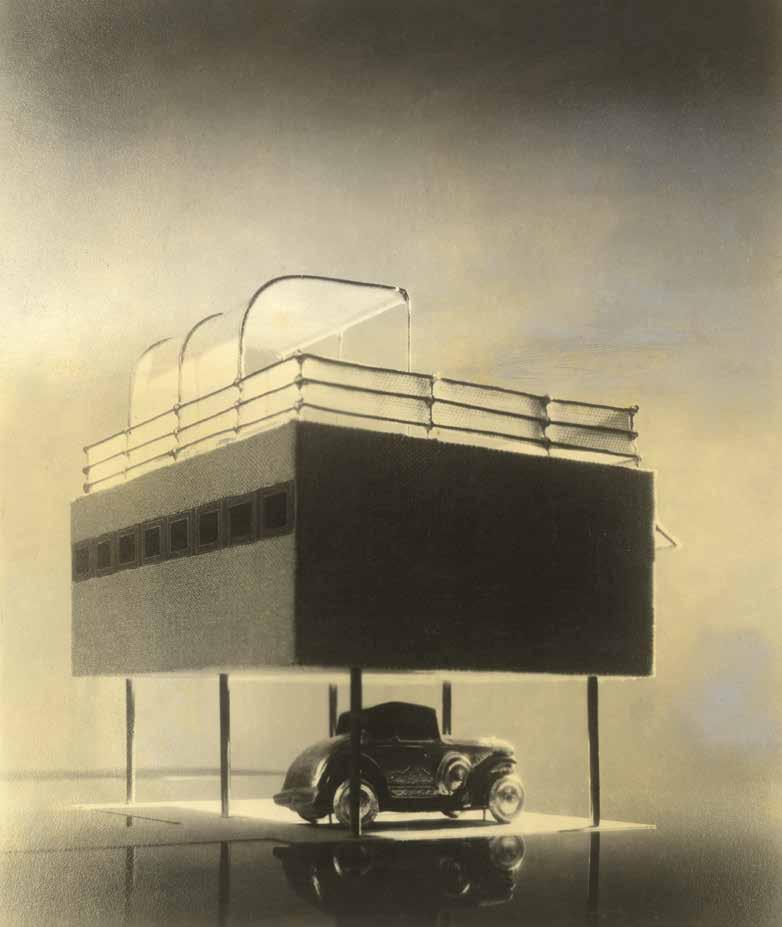

Figure 1.11. A. Lawrence Kocher and Albert Frey. Aluminaire House. Preliminary project 1930. Axonometric view of the structure.

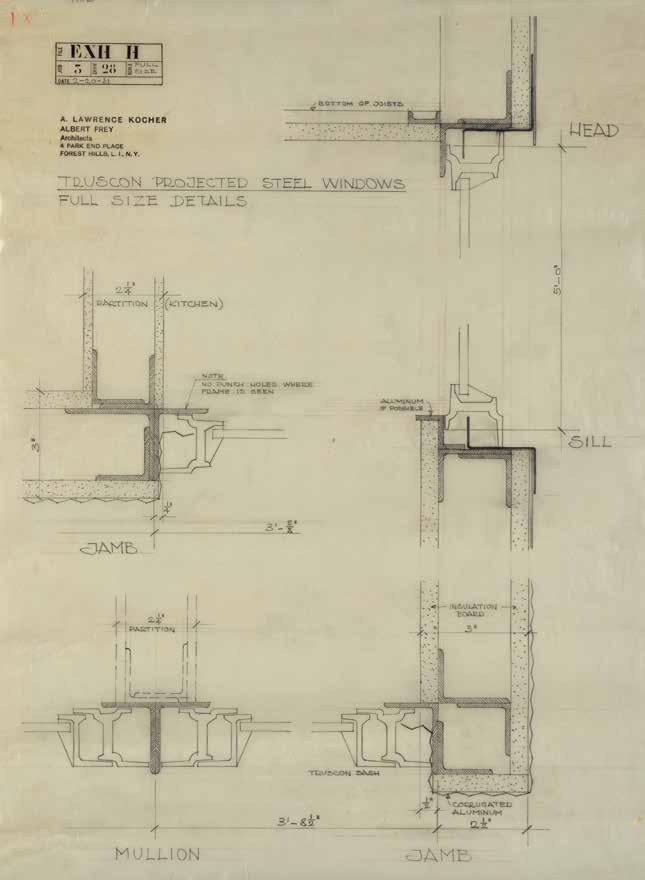

Figure 1.12. A. Lawrence Kocher and Albert Frey. Aluminaire House. Preliminary project 1930. Details for mullions and jambs.

AR+D Publishing

Figure 1.31. A. Lawrence Kocher and Albert Frey. Aluminaire House. Map of Aluminaire House’s itinerance. 1931–1940.

Map of Aluminaire House’s itinerance in the state of New York.

Aluminaire House locations

A. Lawrence Kocher’s residences

Original location at the Harrisons’ estate. 1931–1940.

Final location at the Harrisons’ estate. 1940–1986.

1. Aluminaire House

Existing farm buildings, garage

Dining room

1. Aluminaire House 2. Existing farm buildings. Garage

1. Aluminaire House 2. Existing farm buildings, garage 3. Dining room 4. Living room

1. Aluminaire House

2. Existing farm buildings, garage 3. Dining room 4. Living room 5. Greenhouse

Bedrooms

Kitchen

2. Drafting room.

Dining room

Living room

Greenhouse

Bedrooms

Kitchen

Caretaker’s apartment

Guest rooms

W.K. Harrison’s Office.

AR+D Publishing

1931–1933

THE EXPERIMENTAL WEEKEND HOUSE AND PARALLEL EXPERIENCES

After the Aluminaire House, A. Lawrence Kocher and Albert Frey produced their designs in a transitional social and political context: before and after F. D. Roosevelt’s inauguration on March 4, 1933.1 At the end of 1931, the depression was evident for the majority of the American population. Skyrocketing unemployment rates, along with the failure of banks, businesses, and farms, shattered the optimism of a once-prosperous United States and its middle-class dream.2 The United States government, presided by Herbert Hoover, based its anti-crisis strategy in the dogma of self-reliance deeply rooted in American individualism and the belief that the federal government should stay out of the personal lives of citizens even in cases of dire necessity. Hoover firmly believed that direct aid to the individual was not the business of the federal government but of private enterprise, charity institutions, and local governments.

While unsuccessful in the long run, many private institutions created temporary relief programs, like the sidewalk apple sellers who organized in November of 1930 by the International Apple Shippers Association. Similarly, the Seattle-founded Unemployed Citizens League (UCL) formed in July of 1931; financed by the mayor’s office, UCL organized self-help projects, like cutting wood on donated land, picking unwanted fruit, and distributing food and wood for those most in need. Other private charity institutions and wealthy individuals set up soup kitchens and bread lines for the starving crowds. All of these efforts soon proved to be just a temporary relief—completely inefficient in a scenario of long sustained economic hardship. Adding to the general calamities, in July of 1930, a drought of biblical proportions occurred in the Great Plains, the South, and the Midwest, and Hoover—following his politic of nonintervention instead of using federal means—delegated disaster relief to the Red Cross.

Although faithful to his self-reliance credo, Hoover nevertheless authorized $700 million in public works projects and created a series of agencies to deal with the depression in 1931. A number of them were completely useless and many collapsed in just a few years, like the National Business Survey Conference, the National Credit Corporation, and the President’s Emergency Committee for Employment (PECE)—restructured within a year as the President’s Organization for Unemployment Relief (POUR). Other organizations set up by the Hoover administration were more durable and successful, such as the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) that carried on operations during the New Deal years and had been funded by Congress with two billion dollars “to

provide emergency financing facilities for financial institutions, to aid in financing agriculture, commerce, and industry, and for other purposes.”3 Contemporaneous to RFC’s founding was the White House Conference on Home Building and Home Ownership, which was privately funded and occurred from December 2 to December 5 in 1931. The conference’s aim, and the role of the government within it, was explained by President Hoover:

To undertake the organization of an adequate investigation and study, on a nationwide scale, of the problems presented in homeownership and homebuilding, with the hope of developing the facts and a better understanding of the questions involved and inspiring better organization and the removal of influences which seriously limit the spread of homeownership, both town and country...It, obviously, is not our purpose to set up the Federal Government in the building of homes. But the Conference will, I believe, afford a basis for the development of a sound policy, and inspire better voluntary organization to cope with the problem.4

A planning committee of approximately 20 voluntary associations formed to conduct studies and set up a national conference to analyze and assess the data and recommendations compiled by expert committees.5 For one year prior, about 400 persons prepared studies for the conference, and 1,000 individuals related to building and housing were enlisted to participate in the White House Conference. Twenty-five committees oversaw the study of specific fields within the general problem of housing covered by the conference.6 Six correlating committees dealt with any issue of aim and method that may have been raised, coordinating the initial 25 committees. These correlating committees were devoted to standards and objectives, legislation and administration, education and service, and organization programs—local and national—and technological developments.7 Most of Kocher and Frey’s speculative and researchoriented work during 1931 was directly or indirectly related to several of these committees.

In November of 1931, Kocher and Frey designed a proposal for two low-cost farmhouses, published in 1932 and again in 1934 in Architectural Record.8 The publication included only two plans, model pictures, and a partial axonometric-cutaway view of the construction system. This project was commissioned by the Committee on Farm and Village Housing of the White House

AR+D Publishing

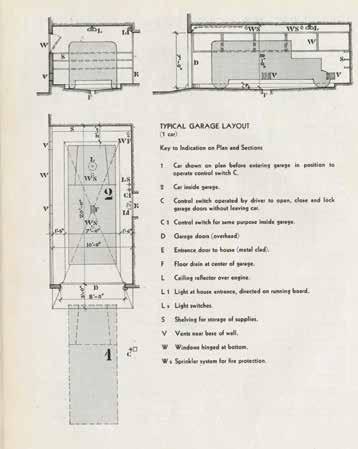

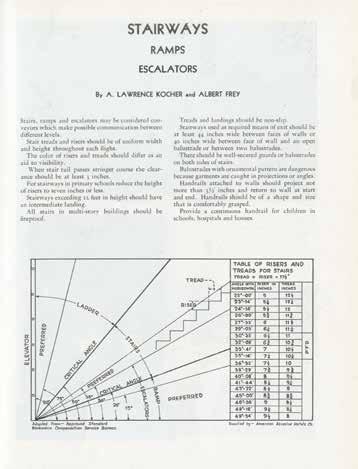

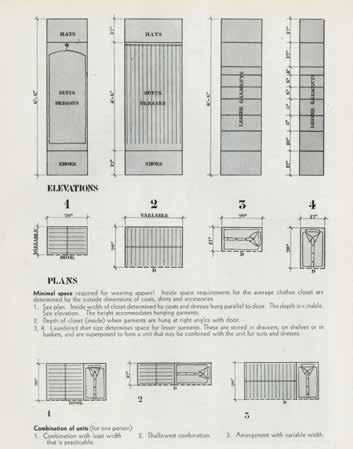

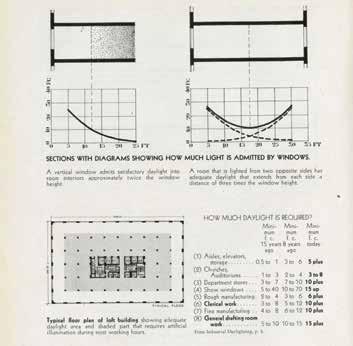

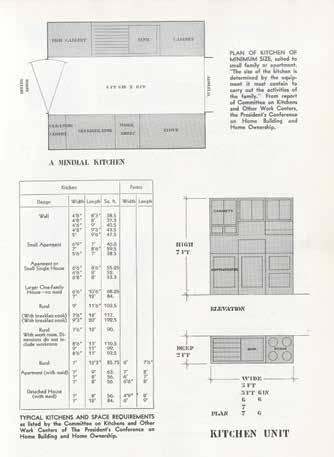

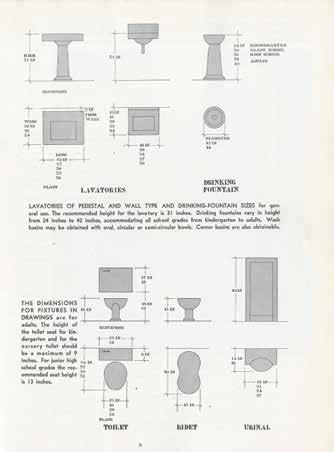

Figures 3.6 to 3.9. A. Lawrence Kocher and Albert Frey. Standard dimensions of housing elements published in The Architectural Record

From top to bottom and left to right: the domestic garage (January 1931), closets (March 1931), stairs and ramps (July 1931), and windows (February 1931).

AR+D Publishing

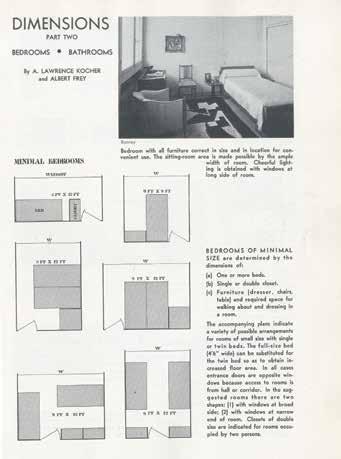

Next page: Figures 3.10 to 3.13. Idem. From top to bottom and left to right: kitchens (January 1932), bedrooms (February 1932), bathrooms (February, 1932), and chairs and tables (April 1932).

1941–1969

INNOVATION AND TRADITION: FROM BLACK MOUNTAIN TO WILLIAMSBURG

A. Lawrence Kocher’s years at Black Mountain College, and more specifically the construction of the Studies Building, were perhaps the most fruitful and rewarding achievements of his professional career as an educator and as an architect. Black Mountain College’s promotion of the advancement of an individual intellectual agenda was not exclusive to students but also extended to faculty. Therefore, these years were for Kocher not only extremely productive in terms of design and construction within the Lake Eden Campus, but also years of feverish activity for his private professional practice. From 1940 to 1943 Kocher developed a series of designs of very diverse scale and scope.

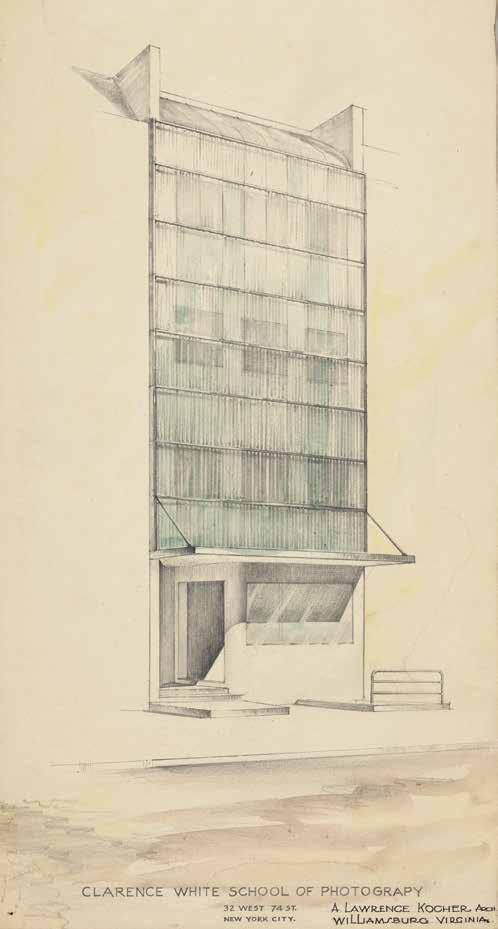

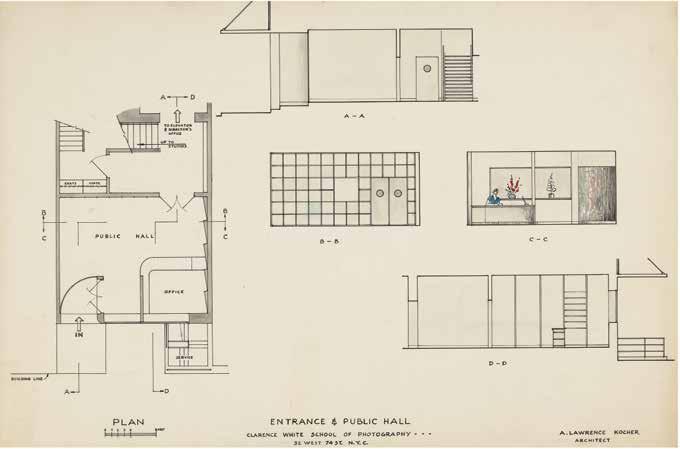

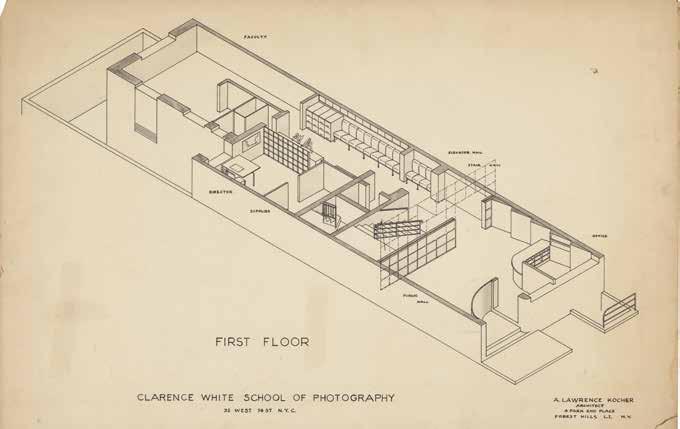

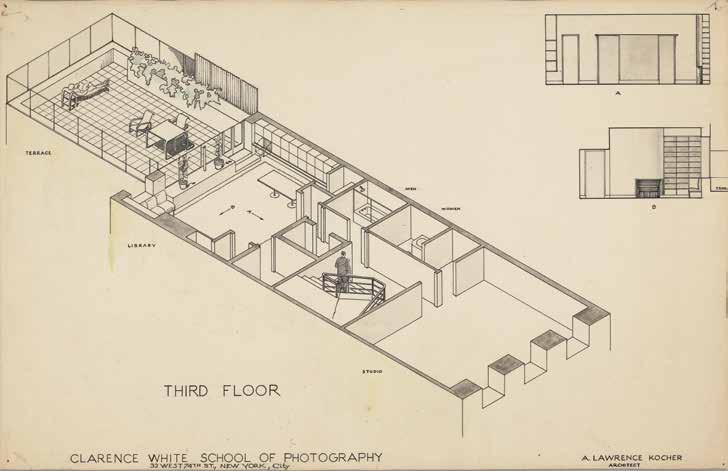

The first of these external projects began in 1939, before Kocher joined the Black Mountain College teaching community. The commission consisted of the renovation of a town house in New York City as the new headquarters of the Clarence White School of Photography. The New York school was founded in 1914 by Clarence Hudson White, a self-taught photographer from rural Ohio, alongside the painter Max Weber. It was a highly influential cultural institution during the 1920s, having among its students and instructors a number of relevant figures in modern photography, such as Margaret Bourke-White, Dorothea Lange, Margaret Watkins, Anne Brigman, Gertrude LeRoy Brown, John P. Heins, Ira W. Martin, Anton Bruehl, Bernard Shea Horne, Walter R. Latimer Sr., Ralph Steiner, and Paul Outerbridge. After White’s death in 1925, the school continued operations run by his wife, Jane White, and their son, Clarence White Jr. The building they purchased in April of 1939 for their new headquarters was a Georgian Revival brick and limestone rowhouse at 32 West 74th Street in New York City.

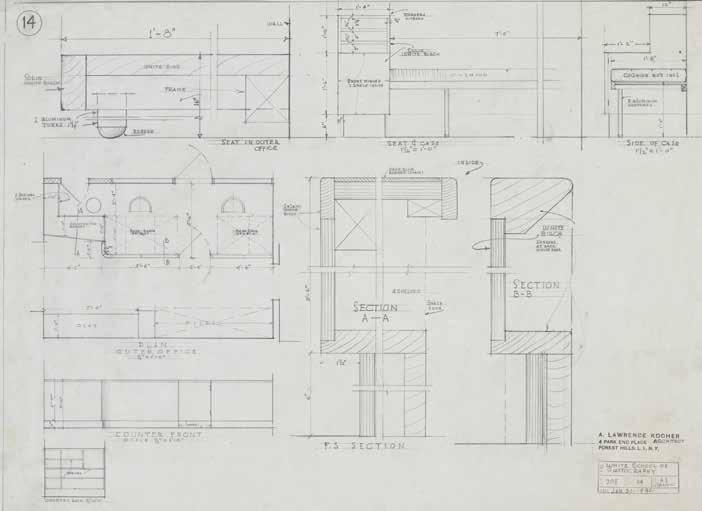

The building was a five-story, load-bearing brick-wall structure that followed the classic New York townhouse typology with the stair occupying the middle of the long and narrow lot, dividing the distribution into two big areas facing front and back façades. Kocher, respecting this basic morphology, proposed a complete alteration of the interior distribution and circulation. To connect all floors above ground, Kocher designed a new stair that, like in Gropius’ Bauhaus building at Dessau, was spacious enough to become the center of all social encounters of the school. The stairwell worked as a modern dynamic stage and showcased student activity with three flights revolving around a central open space that visually connected all levels. Kocher’s new design for the first-floor entry hall had a curved wall to maintain privacy from the main entrance and equipped walls to exhibit photographs produced by the students. (Figures 6.1 and 6.2)

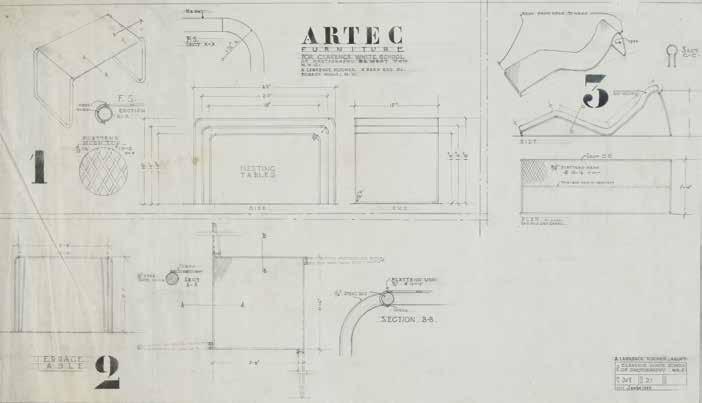

Kocher designed all of the school’s furniture, including the information counter and the seating spaces of this first level, to advertise the school’s output and conceal the institution’s nuts-and-bolts functions.1 Kocher’s architectural conception of the space corresponded with the school’s pedagogical expertise on still-life photography exercises, which seamlessly translated into advertising photography 2

The existing building suffered the most drastic transformation along the 74th Street façade, where Kocher completely modified the first floor to create a modern, functional entry protected by a new cantilevered canopy. He left the rest of the façade untouched but completely covered with a new veil that builds on the strategy of revealing and concealing. The rendering of the façade showed a skin of corrugated glass panels, permitting a filtered vision of the original façade while simultaneously creating a new modern and abstract look over it. As if it were a photographic filter, this glass membrane, depending on the exterior and interior light conditions, revealed or concealed the interior elevation with infinite subtle nuances. The corrugated glass was used in its maximum fabrication size, which caused the horizontal joints to have an offset of half a floor on the third level—a break from the existing building’s established rhythm. (Figure 6.3) The effect of this façade is similar to that of William Lescaze’s own office and house built in 1934 at 211 East 48th Street, yet more radical due to the size and detailing of the corrugated glass versus Lescaze’s restrictive glass bricks. Both projects can be seen as part of a lineage that goes back to Pierre Chareau’s Maison de Verre in Paris, along with other notable projects in Manhattan, such as Lescaze’s Kramer House on 32 East 74th Street (1935) and townhouse on East 70th Street (1941).

The school’s basement floor was dedicated to the technical part of photography, including laboratories, film washing and drying, chemical mixing, printing, and dark rooms. The third floor of the building included a large terrace on the back elevation meant for socializing. (Figure 6.4) Kocher designed a chaise lounge, dining table, a set of small tables, and chairs in expanded metal and chrometube frames. He ordered several furniture prototypes that remained unpaid due to the school falling into bankruptcy in 1942. After photographing them for his portfolio, Kocher used them as gifts to his friends and neighbors William and Betty Bogie. (Figures 6.5 and 6.6) After the school closure in 1943, the complete renovation project was added to Kocher’s unbuilt works portfolio. (Figures 6.7 and 6.8)

AR+D Publishing

The Kaufmann Apartment Building in Pittsburgh was the second commission during Kocher’s tenure at Black Mountain College and

AR+D Publishing

Figure 6.1. A. Lawrence Kocher. 1939–1943. Clarence White School of Photography. Unbuilt. Floor plan of the public hall.

Figure 6.2. A. Lawrence Kocher. 1939–1943. Clarence White School of Photography. Unbuilt. First-floor axonometric view.

came as a direct result of his work there. Edgar Kaufmann Jr. was formerly Frank Lloyd Wright’s apprentice at Taliesin. His father was the owner of the Kaufmann’s Department Store in Pittsburgh and of the Fallingwater House in Bear Run, Pennsylvania (1938).3 In 1941, Kaufmann Jr. visited Black Mountain College during a car trip to Mexico and was deeply impressed by the ongoing construction of the Studies Building. Kaufmann owned property on a ridge of the many hills that overlooked downtown Pittsburgh. He commissioned Kocher to design a four-floor building containing five one-room rental apartments, one primary apartment for his personal use, common services, a garage for six automobiles, and an upper terrace with a common solarium. The high visibility of the construction site and the social prominence of the commissioner resulted in a project with a design approach that Kocher had scarcely explored before. Though architecture historically deals with symbolism, iconography, and meaning, the Kaufmann Apartment Building is the first and only project where a public representation of Kocher’s patron takes a leading role in the process of architectural design.4 Curiously enough, this peculiarity also makes this project the most site-specific design in Kocher’s professional career, otherwise consistently detached from the physical context. These two facts explain the extraordinary emphasis observed in the building’s elevation designs, which work as a public statement of the patron’s status and civic responsibility. The lot was surrounded by wooded cliffs and had excellent views on its north and west sides. The access was only possible through the ridge of the hill that extended to the south. With all these constraints, Kocher—along with the Hungarian emigree László Gábor—drew a variety of building options, paying special attention to the volume, composition, and shadow effects of the more publicly exposed north and west façades, along with the south-access sequence. All these diverse versions can be grouped in three main iterations of the project. The first and least-developed version is a variation of the 1934 plan for the Cotton Textile Institute House, which follows a Z-shape scheme that serves to project and open the building to the views on the north side. The staircase, lobby, common services, and the covered parking garage are simply attached to the south side of this original Z-form. (Figure 6.9) Building on this first scheme, the second iteration of the project has a more compact floor plan, composed of three similarly sized rectangles attached in a clockwise spiral shape, with the stair situated in the middle of the south rectangle. The typical floor contains two one-bedroom, one-bathroom apartments; the ground floor includes common services and a two-bedroom apartment occupying the north side with an enlarged living room that protrudes from the northwest corner and creates a volumetric discontinuity in the public-facing façades.5 (Figures 6.10 to 6.12 ) There are a large number of drawings focusing on the design of this protruding volume and its discontinuity with tentative solutions that range from a very rational and strict disposition of the windows to an expressionist S-shape created through the dislocation of first- and second-floor plans. These options were only explored in elevation drawings and were never reflected on the floor plans. (Figures 6.13 to 6.26)

After these formal experimentations, Kocher withdrew to a more familiar design methodology. Without renouncing the public representation requirements of the project, Kocher and Gabor produced a much more serene, austere, and classically modern

solution, consistent with his body of work. This definitive variation of the project is contained within a simple rectangular parallelepiped; the only discontinuities in this geometry happen on the first floor and in the primary apartment level, again, in search of a more complex articulation of the building’s north-west corner. In this option, all of the service spaces in the apartments accumulate in the south façade alongside a protruding, partially glazed staircase that conforms to a T-shape plan on all levels. The windows of this south façade are narrow, longitudinal sashes that allow for the privacy of kitchens and bathrooms—a contrast to the north façade’s floor-to-ceiling windows, which enable the desired views from the living rooms. Since the project seems to have been abandoned in its preliminary design stage, the materiality and building technology are difficult to guess. Nonetheless, there is a drawing with a plan scheme of the façade’s corner that suggests Kocher’s intention was to use a Transite cement-asbestos corrugated board similar to those used in the Black Mountain Studies Building. (Figure 6.27) The reason for abandoning the project in this early stage is, however, easier to guess, as Edgar Kaufmann Jr. was mobilized in 1942 and served with the US Air Force until 1946, during World War II. (Figures 6.28 to 6.33)

Kocher’s final years at Black Mountain were not only a time of grand historic events, but a moment of complete transformation for the American economy and, most importantly, a period of profound change in the underlying sensibility and common imaginary affecting all levels of American social organization. Even before the official and active involvement of the country in World War II, President Roosevelt committed to the transformation of the United States in the “Arsenal of Democracy” and to the adaptation of American industry to a war-production mode.6 Ford and other automobile producers started fabricating military aircraft and tanks, as shipyards turned out entire fleets of war vessels. This wartime production was the logical continuation of mechanisms put in place during the New Deal, with the state assuming the role as the only purchaser and consumer of industrial production. As wartime production boomed, the increasing demand for jobs, coupled with the mobilization of a large share of the population, dropped unemployment to a historic minimum of 1.2 percent in 1944 from 14.6 percent in 1940. Sixteen million men and women marched to war, while 24 million were employed in defense jobs, often for a higher wage than they previously had ever earned.7 By the time the atomic bombs detonated in Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6th and 9th of 1945, Americans had been living under wartime rationing for over three years. There were limits on strategic materials like concrete, steel, aluminum, rubber, plastic, and petroleum, along with common goods such as shoes, sugar, coffee, meat, butter, milk, and soap; there was also limited vehicle usage and purchase of luxury items. The Office of Price Administration (OPA) encouraged the population to save their money for a more economically comfortable future.8 Americans started purchasing financial products, like war bonds, to help the war effort, and were saving a still-unequaled record average of 21 percent of their disposable income.9 The unprecedented mobilization of workforce and resources, the acceleration of industrial production, and the subsequent rise of employment opportunities and family savings created a relevant impact on the attitudes of the American social body. The Depression-era ethos of austerity and the immediate

AR+D Publishing

This page:

Figure 6.3. A. Lawrence Kocher. 1939–1943. Clarence White School of Photography. Unbuilt. Main façade preliminary sketch.

Figure 6.4. A. Lawrence Kocher. 1939–1943. Clarence White School of Photography. Unbuilt. Third-floor axonometric view.

Opposite page:

Figure 6.5. A. Lawrence Kocher. 1939–1943. Clarence White School of Photography. Unbuilt. Movable furniture.

Figure 6.6. A. Lawrence Kocher. 1939–1943. Clarence White School of Photography. Unbuilt. Fixed furniture.

Next two pages:

Figure 6.7. A. Lawrence Kocher. 1939–1943. Clarence White School of Photography. Unbuilt. Basement plan.

Figure 6.8. A. Lawrence Kocher. 1939–1943. Clarence White School of Photography. Unbuilt. Fourth- and fifth-floor plans.

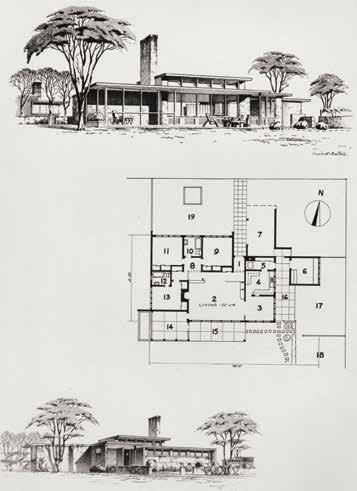

Figure 6.72. A. Lawrence Kocher, Louis W. Ballou, and Charles C. Justice. 1947. Solar House for Virginia. Published documentation. Floor plan and perspective views from the garden and from the street.

Figure 6.73. A. Lawrence Kocher, Louis W. Ballou, and Charles C. Justice. 1947. Solar House for Virginia. Published documentation. Bird’s-eye view of the house.

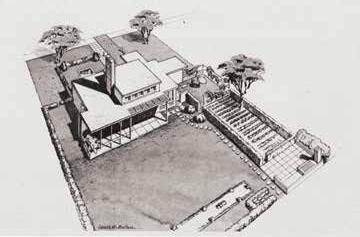

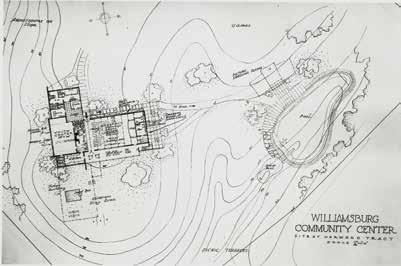

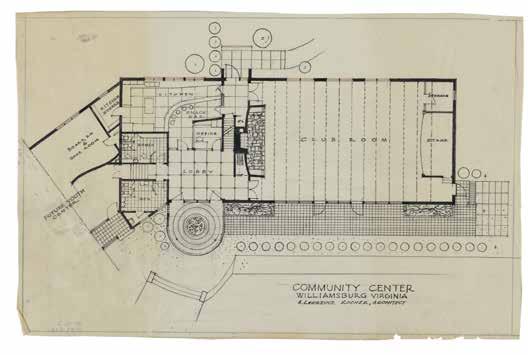

Figure 6.74. A. Lawrence Kocher. Williamsburg Community Center. 1954. Preliminary project. Site plan.

Figure 6.75. A. Lawrence Kocher. Williamsburg Community Center. 1954. Preliminary project. Elevation.

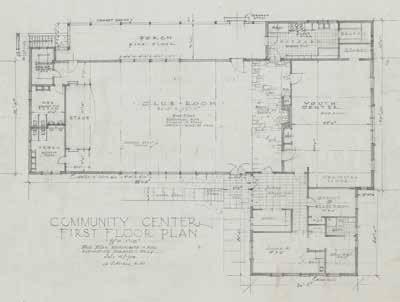

Figure 6.76. A. Lawrence Kocher. Williamsburg Community Center. 1954. Preliminary project. First floor plan.

AR+D Publishing

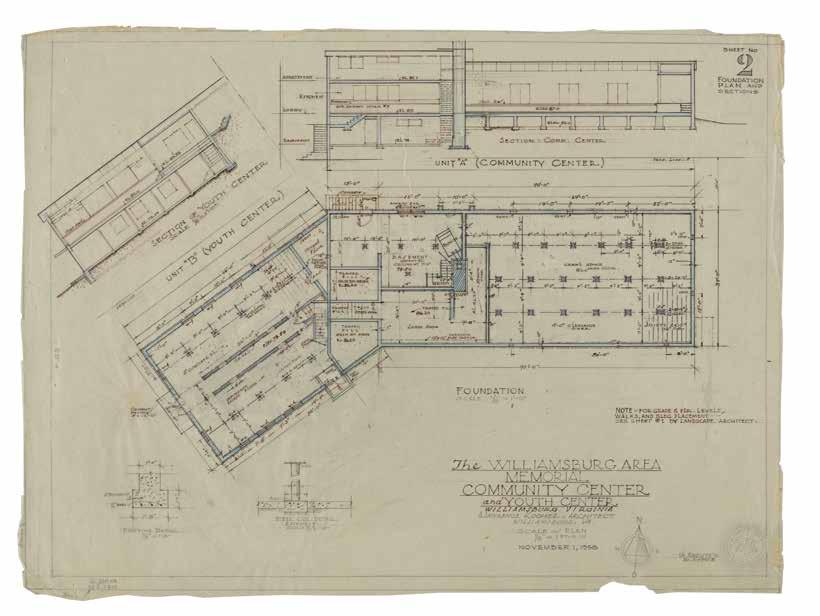

Figure 6.77. A. Lawrence Kocher. Williamsburg Area Memorial Community Center. 1958. Final project. Foundation.

Figure 6.78. A. Lawrence Kocher. Williamsburg Area Memorial Community Center. 1958. Final project. Second floor plan.

01.

02.

Figure 7.3. A. Lawrence Kocher and Albert Frey. Axonometric view of all the case studies. Exterior envelopes.

Aluminaire House 1930 (Built).

Weekend Experimental House 1932 (Unbuilt).

03. Kocher Canvas Weekend House 1934–35 (Built).

04. Florida Weekend House 1937 (Unbuilt).

AR+D Publishing

Figure 7.45. A. Lawrence Kocher and Albert Frey. Kocher Canvas Weekend House, 1934–1935 (Built). Framing plan. Scale 3/16”=1’-0”.

01. Main girders. Double timber beams.

02. Round steel columns.

03. Timber floor joists.

FLORIDA WEEKEND HOUSE, 1937–1939 (UNBUILT)

AR+D Publishing

Figure 7.46. A. Lawrence Kocher. Florida Weekend House, 1937–1939 (Unbuilt).

Axonometric view of the external envelope. Scale 3/8”=1’-0”.

01. Prefab cast-iron spiral stair

02. Dinning room.

03. Kitchen.

04. Bathroom.

05. Living room (day); bedroom (night).

06. Living room (day); main bedroom (night).

07. Storage closets and cabinets. 08. Terrace.