This book is published in conjunction with the exhibition Between Worlds: The Art and Design of Leo Lionni

Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, Massachusetts November 18, 2023, through May 27, 2024

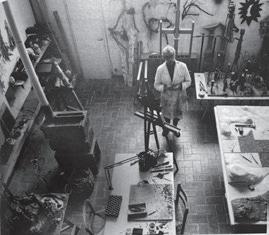

Front cover: Cover art for Frederick (New York: Knopf, 1967). Collage on paper. Back cover: Lionni in his studio, c. 1980s. Photo by Massimo Pacifico. Page 1: Detail of an illustration for Matthew’s Dream. See plate 3.44. Pages 2–3: Lionni with an Olivetti display. See plate 3.15.

The endpapers are inspired by the Olivetti brochure reproduced as plate 1.2.

Editor: David Fabricant

Proofreader: Lauren Orthey

Designer: Misha Beletsky

Production manager: Louise Kurtz

Image credits

Except as noted below, the images herein are courtesy of the Lionni Family. © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris; photo, Art Resource, NY: plate 5.1

© Fortune : plates 3.12, 3.13, 3.67, 3.68, 3.69, 3.70

HIP/Art Resource, NY: plate 5.2

© Museum of Modern Art: plates 1.13, 5.38

© Penguin Random House: plates 4.4, 4.17, 4.18, 4.27, 4.47, 4.56

© Print : plate 3.20

University of North Texas Libraries, Government Documents Department: plate 3.5

Text and compilation copyright © 2023 Norman Rockwell Museum. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Inquiries should be addressed to Abbeville Press, 655 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017.

The text of this book was set in Berthold Bodoni Old Face. Printed in Türkiye.

First edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN 978-0-7892-1470-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request

For bulk and premium sales and for text adoption procedures, write to Customer Service Manager, Abbeville Press, 655 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, or call 1-800-A rtbook

Visit Abbeville Press online at www.abbeville.com.

Acknowledgments

About the Norman Rockwell Museum

Introduction by Annie Lionni

Leo Lionni: A Brief Biography by Stephanie Haboush Plunkett

From Impaginatore to Graphic Designer:

The Graphic Art of Leo Lionni by Steven Heller

The Graphic Art of Leo Lionni: A Gallery

A World in Which to Become Yourself:

The Picture Books of Leo Lionni by Leonard

S. Marcus

Between art and Art:

The Fine Art of Leo Lionni by Ayami Moriizumi and Kiyoko Matsuoka

1.2. Flyer for Olivetti, 1956.

1.3. “At the edge of the woods there was a pond. . . .” Illustration for Fish Is Fish (New York: Knopf, 1970). Colored pencil on paper.

1.4. Aria: Ponte II (Bridge II), c. 1986. Oil on canvas, 31½ × 47¼ in. (80 × 20 cm).

In fact, Leo took great care to maintain the separation of the three spheres of his creative endeavors until, late in life, two museum shows— one in Bologna (1990) and one in Japan (1996)—brought them all together. He was nervous at first about how the shows might be received but soon realized that both put forward the best of his work, and that he was established enough not to suffer any negative consequences. Let me point out that Leo was eighty years old by the time the first of these shows was mounted, and he understood that age and experience were great advantages that had finally allowed him to be seen in all his creative variety. He still believed that the world would not be so welcoming to newer artists who expressed themselves in so many different genres. He and I discussed this issue on multiple occasions. Now, looking back at Leo’s legacy, it is hard for me to see his three creative areas as separate and distinct. The influence that each had on the others was enormous. I see them now as “variations on a theme.”

1.10. Cover illustration for The Greentail Mouse (New York: Knopf, 1973). Oil on canvas board.

1.11. Illustration for The Greentail Mouse. Oil on canvas board.

Leo also had a special fascination with masks and profiles. He painted and sculpted these related motifs (plates 1.8 and 1.9), and included them in his children’s books. The Greentail Mouse (1973), for instance, is about a community of mice who wear masks—most often shown in profile—at first simply as part of their woodland Mardi Gras celebrations (plate 1.10). Later, however, the mice find another, darker use for their masks as they succumb to the negative impulse to employ masks to frighten others while concealing their identities from one another (plate 1.11).

He painted profiles of faces on wood, cut them out, and assembled them in front and back of each other as if in a crowd (see plate 5.20). He carved hair combs into the shape of human profiles and made three-foottall marble carvings of faces in profile. He created a small artist’s book in which each different-sized page is a cutout of a face in profile.

Lionni returned to Italy in 1960, at the age of fifty, and settled in Tuscany, where he created paintings and large, fantastical sculptures in iron and brass inspired by nature. The Lionnis remained in Italy on a full-time basis until 1980, after which they split their year between New York and Italy. Lionni’s accidental entry into the world of picture books allowed him to meld the worlds of fine and applied art and share humanistic messages through the use of animal metaphors that appealed to children and adults. Little Blue and Little Yellow (1959), his first published book, was the outcome of his attempt to entertain his grandchildren on a train ride by spinning a warm tale of friendship and togetherness with pieces of paper torn from a copy of Life magazine. (At the time, he was still art director of Fortune, another Time Inc. publication.) He would go on to write and illustrate more than forty picture books—short, lyrical fables offering meaningful life lessons, with artful, imaginative visuals created in collage and other media. Lionni was the recipient of four Caldecott Honors for excellence in illustration, for Inch by Inch in 1961,

Swimmy in 1964, Frederick in 1968, and Alexander and the Wind-Up Mouse in 1970. Individuality, creativity, friendship, community, and the common good are recurrent themes in his deceptively simple, multilayered stories, which were often developed in his farmhouse in Italy (plates 2.8 and 2.9). “I believe that a good children’s book should appeal to all people who have not completely lost their original joy and wonder in life,” the artist said. “I make them for that part of us, for myself and my friends, which has never changed, which is still a child.”

As a personal project, Lionni created a richly detailed world of imaginary plants, dubbed “Parallel Botany,” that he depicted in drawings, prints, sculptures, and paintings (plate 2.7). His book based on this project, intended for an adult audience, was published first in Italian as La botanica parallela in 1976, and then in English as Parallel Botany a year later. The book’s detailed drawings and fantastical text—including plant descriptions, travel stories, folk etymologies, and historical details—are a reflection of Lionni’s lifelong and deeply felt connection to the natural world.

Diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 1982, Lionni would continue to write, illustrate, and conceive of new projects for more than a decade to follow. Having enjoyed a prolific and multifaceted artistic career, Lionni died at his home near Radda in Chianti, Italy, on October 11, 1999, at 89 years of age. Lionni’s brilliant and timeless vision remains a touchstone, and an inspiration, for artists and art lovers across generations.

2.7.

2.8.

2.9.

One of the most satisfying accomplishments of Lionni’s design career was his short tenure, in 1955–56, as coeditor and art director of Print, the premier graphic arts trade magazine for decades (plates 3.19 and 3.20). In his time at Print, Lionni elevated graphic design journalism and commentary, providing a platform for varying disciplines and points of view. He opened up the design field—then as now polarized between the classical and the modern designers—to history and invention, through in-depth coverage of international trends and national currents. He wrote a column titled “The Lion’s Tale,” a review of art and design phenomena. Print was an example of Lionni’s rationalism in the service of his colleagues and his art. “I’ve looked back on those issues,” he proudly said, “and they are very civilized.”

The idea of creating, in his words, “civilized and human” art became Leo’s obsession. After all his tangible accomplishments, he explained, “I felt the only way I could really reach my goal was by doing painting, sculpture, writing and graphics the way I wanted to do it.” His professional career, except for a few found moments to study mosaics, had been in the service of others. “Everything I had done was a happy compromise that I’ve never felt ashamed of in the least.” But the time had come for movement. At fifty years old, at the peak of his endeavors, Lionni left Time Inc.; moved to Italy, where life was less expensive; and followed his muse. “Everyone thought I was crazy because I had very little money, but it was what I needed to do.”

Yet his self-imposed exile from the media world was not cast in bronze, as were the sculptures he began to create in Italy. Just before he left on 3.19

3.17. Entrance to Unfinished Business, the U.S. pavilion at the Brussels World Fair, 1958. The pavilion was designed by Lionni and sponsored by Fortune.

3.18. Model of an exhibit in the Unfinished Business pavilion.

3.19. Cover illustration for Print, April / May 1956 (Italian issue).

Protecting America’s Protection!, advertisement for the Container Corporation of America, 1941.

3.67. Cover design for Fortune, June 1955.

3.68. Cover design for Fortune, March 1956.

3.71. Cover of Designs for the Printed Page, 1960. This promotional publication for Fortune, meant to showcase the magazine’s printing and design capabilities to advertisers, features colorful abstract designs by Lionni.

3.72–3.80. Interior spreads from Designs for the Printed Page

4.18. Cover of The Alphabet Tree (New York: Knopf, 1968).

4.19.“Some made short and easy words like dog and cat. . . .” Illustration for The Alphabet Tree. Pencil and rubber stamp on paper.

4.20.“The letters had never thought of this. Now they could really write—say things.” Illustration for The Alphabet Tree. Pencil and rubber stamp on paper.

4.21.“The letters tried to think of something important, really important.” Illustration for The Alphabet Tree. Pencil and rubber stamp on paper.

as an artist, it was within her power to make more art (and, it turned out, music too) that would last; and that the essence of an artwork lay not in the object but the idea and spirit behind it. Years later, in another book about mice called Matthew’s Dream, Lionni again reflected on the special power of art to make life better: better for children, whose capacity to imagine their own future lives might be greatly expanded by an early experience of art; better for artists, who found, in the work they devoted themselves to, the sense of purpose that most everyone wants; and better for all those who were touched by an artist’s vision, a group (as was the case with Lionni himself) that might cross generations and extend half a world away (plates 4.32–4.36).14

walk amongst the women and “enter into the painting” (plate 5.20), becoming one of the characters in the story that was staged.

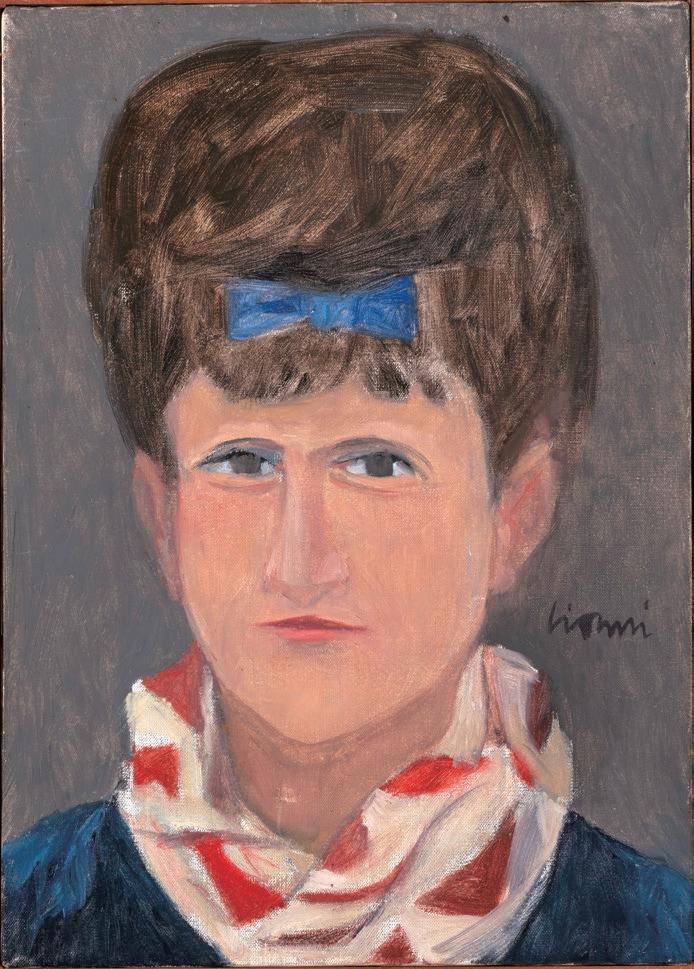

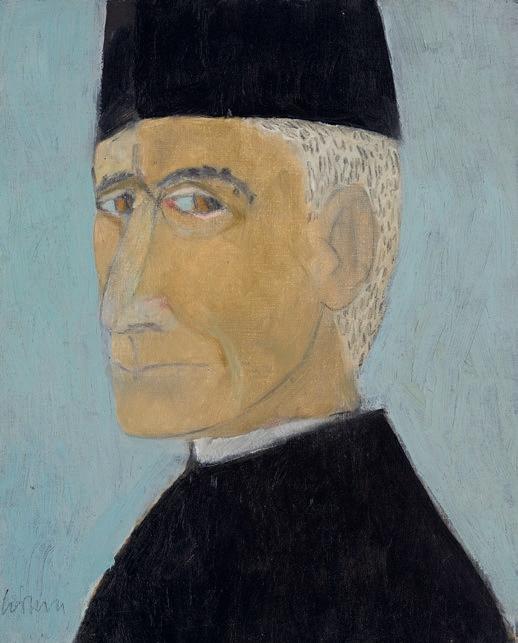

The change from frontal view to profile is an example of how Leo proceeded as an artist in the second half of his life. Following his “urge” and instincts, Leo would work on a certain project for up to ten years. When he reached the point of saturation, he would oscillate toward the “opposite” direction.

5.17. Ritratto immaginario: Annamaria, 1963. Oil on canvas, 14 × 10 in. (35.5 × 25.5 cm).

5.18. Ritratto immaginario: Prelato, 1962. Oil on canvas, 115⁄8 × 91⁄2 in. (30 × 24 cm).

5.19. Reproduction of works from Cesare Zavattini’s collection of self-portraits. At center is Lionni’s self-portrait from the Imaginary Portraits series, c. 1964.

Stephanie Haboush Plunkett is the Deputy Director and Chief Curator of the Norman Rockwell Museum. The curator of many exhibitions relating to the art of illustration, including Tony Sarg: Genius at Play ; Imprinted: Illustrating Race; Enduring Ideals: Rockwell, Roosevelt, and the Four Freedoms ; Inventing America: Rockwell and Warhol ; and The Unknown Hopper: Edward Hopper as Illustrator, she has held positions at the Brooklyn Museum, the Brooklyn Children’s Museum, and the Heckscher Museum of Art. She leads the Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, the first scholarly institute devoted to the study of illustration art, and has written and spoken widely. Her recent publications include “The Shifting Postwar Marketplace: Illustration in the United States and Canada, 1940–1970” in History of Illustration; Drawing Lessons from the Famous Artists School ; Norman Rockwell: Drawings, 1911–1976; Imprinted: Illustrating Race; and Tony Sarg: Genius at Play.

Ayami Moriizumi earned her master’s degree in comparative literature and culture at the University of Tokyo, and she has also graduated from the University of Bologna with a thesis on Baroque machine. Since 1991 she has collaborated with Kiyoko Matsuoka on the Bologna Children’s Book Fair Illustrators Exhibition in Japan, as cocurator and researcher. Moriizumi also specializes in giving lectures on art history and picture books and in conducting cultural, linguistic, and artistic workshops for children. Her most recent publication is Daremo Shiranai Leo Lionni (Leo Lionni: What We Didn’t Know; 2020), cowritten with Kiyoko Matsuoka.

Kiyoko Matsuoka earned her master’s degree in pedagogics at Chiba University and is currently director of the Itabashi Art Museum in Tokyo. Since 1989, she has been the organizer of the BCBF Illustrators exhibition in Japan. From 2010 to 2014, she served on the executive committee of the International Board on Books for Young People. Matsuoka has curated many exhibitions on children’s book creators, such as Bruno Munari, Iela Mari, Tomi Ungerer, Mitsumasa Anno, Katsumi Komagata, and Taro Miura. Together with Ayami Moriizumi, she has curated three exhibitions on Leo Lionni, in 1996, 2018, and 2020. Her publications include Leo Lionni: Kibo no ehon o tsukuru hito (Leo Lionni: A Message of Hope; 2013) and, with Ayami Moriizumi, Daremo Shiranai Leo Lionni