In the beginning Amany is the radio from the desert. Or at least, that’s what her bedridden granddad in Aleppo calls her. She imagines stories for him, inventions in which children cut a path beyond the house, which is bolted on the inside and is built on the edge of the oasis. What Amany remembers most are the intrepid princesses, who travel alone to places where the doors are open and no rooms are forbidden. The grandfather and the child only see each other in the summer, when Amany and her six brothers and sisters swap

a Saudi provincial city for the native land of their parents. Syria is always a rainbow-coloured feast: the whole family picnics in the park or passes the time on the beach, gaping at the elegant women and innocently playing children. Whenever they get a chance, the girls lick sorbets, wearing the flower-pattern dresses that their mother tells them not to take with them when they leave. Even though they know the rules, this always ends in tears.

In Amany’s mind Saudi Arabia is black, the black that swallows up everything. All other colours, dreams, bodies and lives alike. It begins when she is eleven. Her three-year older sister Shada gets a room of her own, she’s allowed to accompany their mother to the bath house and travels to Riyadh with her on family visits. These trips take an intriguing turn, as they invariably end in Shada barricading herself in her room for days on end.

Things go on like this for years. Shada’s privileges amaze and upset the other children, even if she herself doesn’t seem to care. She is thin as a broomstick and hardly ever laughs. Mother offers no explanation, father comes home ever later, and angry winds rage at school. Rumours, wild stories—according to gossip, Shada is on the verge of collapse.

But how would anyone know? The girl hardly spends any time at school. And after that one afternoon, she refuses to attend at all. Amany remembers it all too well. A scuffle breaks out on the playground. Shada gets pushed, many hands tug at her long garments. She staggers, lets out a scream, and freezes. The baldness of her scalp leaves onlookers breathless. But soon dismay turns into mockery. That evening, mother warns her anxious children that their patience is being tested. By tormentors who want

“Russian aircraft caused the death of numerous children and families, despite Moscow’s assertion that it avoids targeting civilians.”

there’s also that Frenchman who wants to tell her story and who promises her a future in Paris. Under one condition, though: that the film ends with her unveiling. To make it stronger, more dramatic. And to keep the viewer captivated. Amany won’t even consider it. Not yet. The hijab is of no importance to her, but it is to her family. And she doesn’t want to lose them.

Alaa and Alisar’s offer on the other hand is unconditional. As long as their cameraman Abdo—who himself lives in Idlib—can spend 6 to 7 hours at Amany’s home every day. In an acceptable setting, in the company of her niece, Bisan. The girl could use a new adventure anyway. The bombings destroyed her father’s shop and ruined the family. Bisan was so traumatised that her hair fell out. Her classmates bullied her for wearing a cap, until Amany taught her how to fight back.

The family is firmly against the film project, but Amany persists. She has turned 36 and needs to tell her story. That’s all there’s to it. She harbours no illusions. By now, she is not unlike the type of woman that is given as a bride to Islamist fighters returning from the front lines. Mind you, it almost got to that. Recently, a commander stood on their doorstep. In her presence, he came to negotiate with her mother as if he were purchasing livestock. You should have seen his face when he was escorted out. Amany still laughs about it.

Some call her an eccentric woman of means, while others consider her a stain, a woman to be avoided, like a plague of lice. Take Thala, the twenty-year-old whom Amany befriends at an English class. The girl dreams of playing the oud, and Amany surprises her with an instrument and a prepaid private course. However, things

“My name is Mariana but they call me Mar. I live in Mexico City, a place that I both loathe and adore. I enjoy drawing and embroidery I love fashion and old clothes. I am a Virgo by zodiac sign, I’m queer, and I cry a lot.” This is how the young Mexican artist describes herself on the internet. Not as Mariana Lorenzo, but as Mar Maremoto. The latter is Spanish for tsunami, intended as a confession of exuberance.

In recent years, Mar Maremoto has experienced a whirlwind journey. Turning her vulnerability into rocket fuel, she’s conquering both the virtual and the real world.

Painted, sewn, or drawn her colourful, dissident bodies are everywhere: on murals, posters, illustrations, cards, and labels.

Mar was an Instagram girl before the platform even existed. She lives in images, in doodles, and in scenes from movies and series. It has always been this way, like a string of solace guiding her through the days. They are stepping stones, amulets against an occasionally overwhelming unease.

The first stepping stones consist of the Holy Virgin of Guadalupe – a sixteenth-century saint associated with motherhood, feminism, and even social justice – and the Argentinian comic hero Mafalda, who despises capitalism, authoritarian regimes, and soup. She loves the Beatles, has a turtle named Bureaucracy, and asks her perpetually toiling mother whether being a social failure is hereditary.

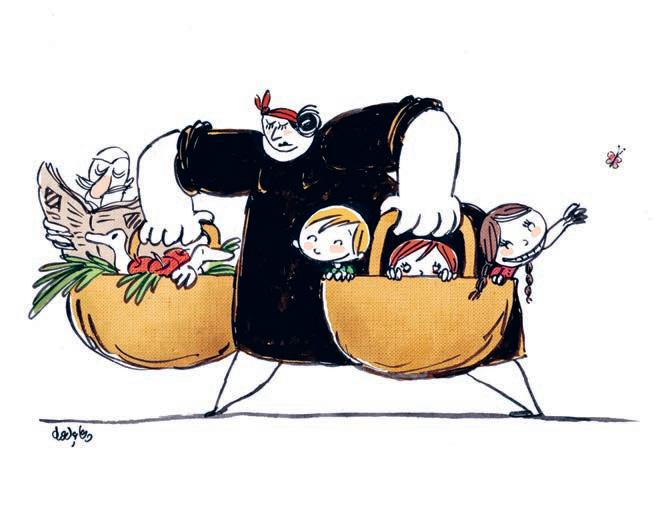

Then, Mar swirls into A series of Unfortunate Events, 13 books illustrated by the American Brett Helquist. In them most adult characters are depicted as total idiots, easily manipulated by a tireless madman. Two young orphans are the only ones who see through him, but whoever listens to children? Mar identifies with these kids, as well as with the bored protagonist of the American film Coraline, based on a Neil Gaiman novella. At night, Coraline follows mice into the Other World, where Other mothers and Other fathers seem to shower their children with attention and love. For that film a knitter of miniatures was required, who took months to sew six pairs of silk mini-gloves, made with needles no thicker than a human hair. Mar is bowled over; she can’t have enough of the behind-the-scenes footage.

Later, the werewolves and vampires of Twilight make their appearance. Mar doesn’t understand why all the girls are crazy about the male protagonists in the series; secretly,

“I’m not yours, I’m not anybody’s, I’m mine only.”

“Dancing, twerking, shaking, enjoying our bodies is not only freeing but a deeply political action. With the lyrics of Mia, a perreo from Puerto Rican artist Bad Bunny, I wanted to draw a womxn having control over her body, enjoying it while she’s perreando (Spanish word that means ‘to twerk’ or ‘dance to reggeaton’).”

mother into action prove equally fruitless. The woman keeps her lips sealed; she has no time for the desperate girl. “Close the car door,” she snaps and steps on the gas pedal.

Mar’s mother considers youth a highway to growth and development that tolerates few breaks in the parking lot, let alone wrong turns. Her children are racing cars, shining in the strength of their young years. She wants a good

“My body is mine. The choice will be mine.”

“A womxn is hugging herself. She is surrounded by a rich garden. Her own place in the world, by her own side. This illustration was made using the work of Mexican photographer Giselle Desavre as a reference.”

education for both, in addition to soccer for the son and ballet for the daughter.

At first, Mar is enthusiastic the tulle tutu enchants her childish heart but soon the classes become a torment. She is only eight and already oversized. Mar-the-ballerina turns into an endless calvary of dieting, and of all conjugations of guilt and penance. The chance of having a normal relationship with treats is forever lost. Colourful cards with

Two stick figures in black and white, a single line of text, and the suggestion that the judges are being hand-fed by the ruling Hindu nationalist BJP. That was the content of one of the three cartoons that landed the Indian cartoonist and activist Rachita Taneja in the dock in December 2020. Whether she will be found guilty of contempt remains to be seen, but the message is clear. India’s democratic space is shrinking as dangerously fast as the groundwater in the soil.

Nevertheless, Rachita refuses to be defeated: she continues to question the rising authoritarianism in the

8 March ... Women’s Day

Her training as a painter of theatre and film sets is downright disappointing; yet the years in Alexandria are the best of Doaa’s life. She learns everything she needs in the fabulous institutions of this ancient, cosmopolitan city. At L’ Atelier d’Alexandrie, the independent art centre that was founded in the 1930s, Doaa first starts to live outside books. She goes to concerts, joins a poetry group, falls in love, and takes part in long discussions about the sufferings of the Palestinian people. The bulk of her free time is spent in this old villa—where once the work of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Henry Moore and Auguste Rodin have been on display.

Doaa enjoys life to the fullest until the inevitable return to Damietta approaches like a battleship on the horizon,

keeping her awake at night. There’s no holding on to Alexandria after graduation, no matter how much she frets and ponders.

Returning to her parents’ place feels like back to square one. At 23 Doaa has her first job, as an interior decorator’s assistant. Her life resembles the antique clocks she’s supposed to sell. They run down unnoticed, accumulating dust. Her mothers’ secret schemes for marrying her off by sending one potential suitor after another to the antique shop make it all the more miserable. In the end Doaa scrutinises every male customer, wondering if he’d be on her mother’s list? She shrugs at the thought; she won’t have any of it: marrying in Damietta means being buried alive. Her unhappiness does not go unnoticed, or so she

eternal dictator. The floodgates have opened, but the price is extremely high: hundreds of citizens are killed and many more wounded or maimed.

In Doaa’s memory the revolution is a mediocre action film, with an excess of dangerous scenes. Pursuits by vicious police, confrontations with mobs hired by the state and narrow escapes. But there is also the solidarity of strangers, the safe shelter offered by an old woman who has transformed her shabby room into a realm for stray cats.

The paper Doaa works for can’t be published—there is no phone or internet—but she and her colleagues produce cartoons all the more. Day after day they distribute them on Tahrir Square. To increase the morale of the demonstrators and to get a taste of the impending freedom. The day that Mubarak is removed from power, she says, is the happiest of her life.

The impossible has been achieved, but it never develops into more than a deceptive honeymoon period. Fifteen months later, when the country’s first democratic presidential election is held, all hope of a better future has dissipated. Doaa doesn’t even bother to vote. “The truth is that the Brotherhood and the army are the organised political factions, both are standing against democracy and preventing the existence of a civilian current... They deprived us of having a third choice... for civilians to rule... and for there to be parties. A normal political and civilian movement.”

The Egyptian citizen has been allocated a tasteless role as an extra in a farce tautly directed by the army. Had the outcome been less tragic, one might have admired the cunning with which the game is won. Think of it as the

My Soul will never be defeated - against sexual terrorism on Egyptian Female Protestors

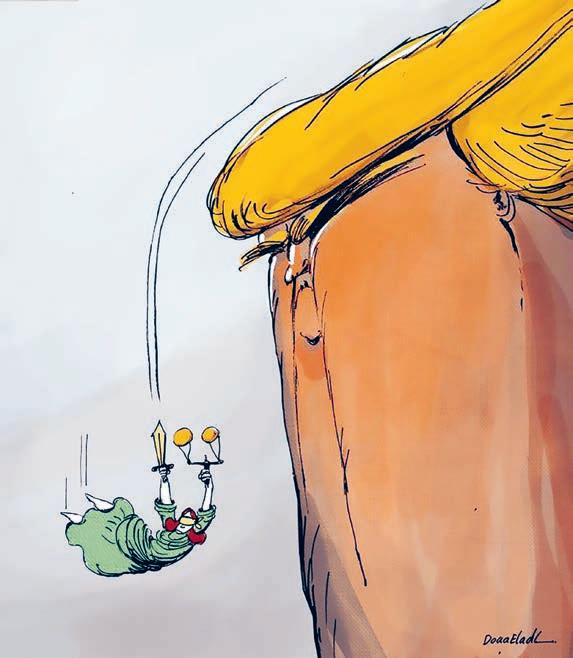

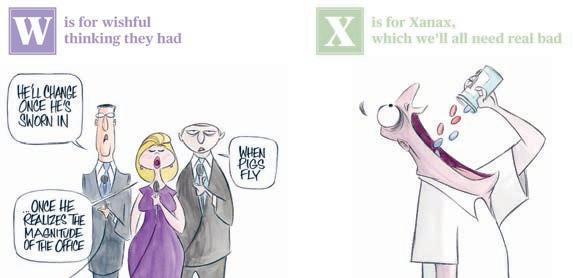

“From the Trump’s ABC book, a satirical look at the Trump presidency in the format of a children’s book.”

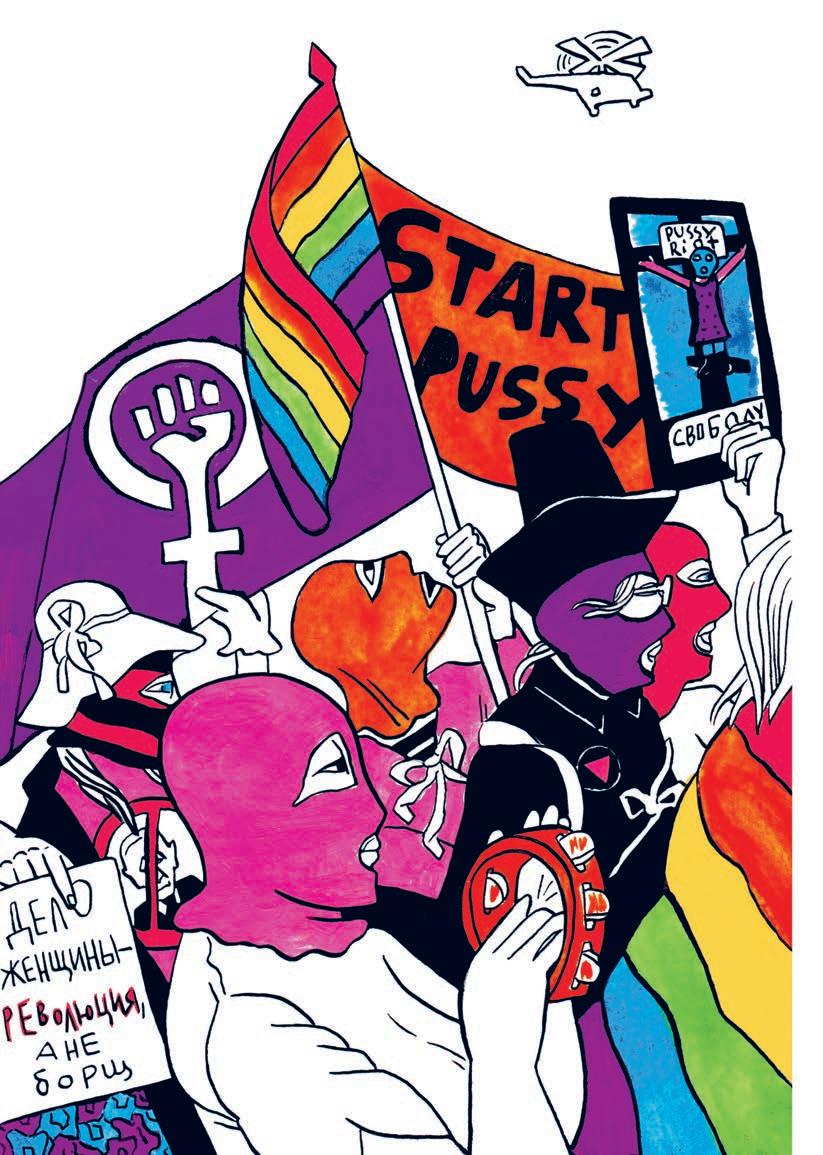

“A woman’s work is revolution, not soup.”

Draw for Change

“Glory to Russia!

“Put Pussy Riot in the trash!”

Victoria Lomasko

Victoria grows up in a two-room flat in a concrete block, where bitterness prevails over affection. Most days she spends hours on end drawing. A kind word from her father is as scarce as the chocolate or the toys from the GDR that her mother purchases on the rare occasions she takes her daughter to the capital.

Her grandmother’s old cottage on the edge of the city is the only place where Victoria feels happy. She spends many an hour there under the apple tree with its decaying roots, imagining herself as one of its branches. Her granny lives as a contented hermit, closed off from all the corrosion of communism. Her universe is a mixture of time capsule

and fairy tale in which the names of the red prophets and the feats of their disciples are never mentioned. Granny only talks about her memories and her garden, a world that sways back and forth with the seasons. It extends beyond the bread, the potatoes, the pickled cabbage, and the vodka that shape the boundaries of all the normal days in the Soviet Union—in her house there are home-grown vegetables, strawberries, candles, religious icons and tea is gulped down from a saucer.

All of this is light years away from the world of school. At the age of seven Victoria is enrolled as a member of the Oktyabryata, the young Octobrists. Call it indoctrination for beginners: they are given a ruby-coloured star with the portrait of Lenin, the father of the nation, a kindly granddad figure. As the protagonist of many a children’s book, he achieves the impossible for the welfare of successive generations. Initially Victoria is convinced he’s hers alone; how can it be that she has to share him with other children? If that is how it is, she tells her mother, she’ll choose to be Lenin herself.

A few years later Victoria joins the Young Pioneers but by then all her zeal has evaporated. If the Little Octobrist believed that the future is an exciting world, full of adventures, the ten-year old makes no attempt to hide her lack of enthusiasm when her teachers talk about the blessings of the Revolution. The country is on its last legs; even before she’s supposed to join the Komsomol (the Communist Party’s youth organisation), the Soviet Union has ceased to exist. What follows is an unending nightmare: inflation swallows up any savings, crafty apparatchiks go off with the state funds, the bulk of all the state companies is forced to close. Millions of people lose the only job they’ve

This book was developed along the series Draw for Change.

Texts

Catherine Vuylsteke

Translation

Donald Gardner

Interpreter for interviews with Amany Al-Ali

Alaa Amer

Book design

Freek Lukas & Mies Van Laere, repress.design

Cover Image

Mar Maremoto

All images copyright of the artists, except for p.142 Bea Borgers, p.162 Copyright Victoria Lomasko, courtesy CartoonMuseum, Basel p.150, p.160, p.163, pp. 164-165, p.166, p.167, p.169 Copyright Victoria Lomasko, courtesy Edel Assanti, London

If you have any questions or comments about the material in this book, please do not hesitate to contact our editorial team: art@lannoo.com

© Lannoo Publishers, Belgium, 2023

D/2023/45/297 - NUR: 644/646

ISBN 9789401496025 www.lannoo.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders. If, however, you feel that you have inadvertently been overlooked, please contact the publishers.