The Matrix of Struggle

Pablo Echaurren’s Quadratini

Daniel Spaulding

In the only surviving photograph that shows Pablo Echaurren in the company of his father, the Chilean painter Roberto Matta, the young artist-to-be appears in Rome’s Piazza di Spagna wearing an incongruous coonskin Davy Crockett hat. This was an early indication of an elective affinity with the American frontier that crops up throughout Echaurren’s subsequent artistic and political endeavors, and which indeed remains strong to this day. By the same measure, little Pablo’s pointedly un-Italian sartorial choice is a sign of a collective infatuation with the mythology of the West that gripped an entire postwar generation, echoing throughout various registers of 1960s culture both high and low – most famously, in the Spaghetti Westerns that ultimately succeeded in re-exporting a European fantasy of an American fantasy back to America itself. When Italy’s decade-long “Creeping May” debouched in the chaotic Movement of ’77, it was only logical that Echaurren would reemerge as a core member of the notorious Indiani Metropolitani (Metropolitan Indians), whose playful militancy consummated a shift in political and aesthetic identification from one pole of this structural dyad to the other: that is, from cowboys to Indians (from settler-colonial culture hero to nomadic war machine).1

As problematic or simply strange as it might appear from a contemporary perspective, this extended practice of cross-cultural make-believe is comprehensible as a dialectical inversion of the moral order of Italy’s capitalist reconstruction during the preceding Marshall Plan era. This development was long in preparation. By the late 1960s, a series of metonyms suggested itself all-but automatically to young Italian radicals, reared, as they were, on the contradictory libidinal economy of a fierce (professed) anti-Americanism combined with an unavoidable immersion in the dreamworld of the American culture industry. In classic Westerns, Native Americans and Mexican bandits had always been coded as enemies of the white homesteader’s bourgeois virtues. In the context of the Vietnam War and the decolonization struggles of the 1960s – to which many Italian leftists found their own country’s quasi-colonial situation analogous, not so implausibly given the heavy-handed US interference in Italian domestic politics during the postwar era – it made sense to reverse the polarity by valorizing Native Americans, guerrilla fighters, and countercultural dropouts alike as somewhat interchangeable figures of anti-imperialist insurgency. Even in mainstream film, directors

1 To be more precise, by his own account Echaurren was attracted to Davy Crockett because he was neither a cowb oy nor an Indian (personal communication, June 2022). Frontiersmen, trappers, and guides are mediating, ambiguous figures, always at risk of “going native.”

such Damiano Damiani and Sergio Corbucci made the connection explicit in the politicized cinematic mutation sometimes known as the “Zapata Western,” which revealed the bankruptcy of the Old West’s allegorical parties of order.2 The tendency had its impact on fine art as well. Italy’s most prestigious postwar aesthetic export, Arte Povera, was after all originally conceptualized as a quite literal counterpart to guerrilla warfare; Mario Merz’s glass domes (some of the most iconic works to have emerged from the movement) in turn recall transitory dwellings such as igloos, tipis, and yurts.3 In this epochal reimagining of well-trodden mythic territory, the Western landscape itself – no less fantastical, no less impeccably un-European than its Indigenous inhabitants – also had its role to play.

This is true not least in the remarkable series of quadratini, or “little squares,” that Pablo Echaurren produced in large quantities throughout the 1970s. It is in these small drawings in pencil, ink, and watercolor that the cultural complex that one might name Italian “Occidentalism” – in analogy with the mélange of projection and otherness that Edward Said famously taught us to call Orientalism – intersects with two apparently divergent imaginings of history: on the one hand, the punctual rhythm of political action, and on the other, the cosmic non-human or super-human time of rocks and stars. Whereas Orientalism projects an “imaginary Orient” that materializes European fears and desires, as Linda Nochlin once argued,4 “Occidentalism” evokes an imaginary West to somewhat similar effect, albeit with a more benign politics (apart from the obvious dangers of stereotyping and cultural appropriation to which the Indiani Metropolitani certainly fell prey). Indeed, in Echaurren’s case, this Western fixation mingled with a related interest in the East, or more particularly in Maoist China, which many European radicals of this period viewed as an alluring if little-understood revolutionary paradise. We should thus add Chinese communists to the roster of insurgent figures. However, my essay does not address this secondary theme at any length. In the following section, I will instead discuss the mythic Western landscape. Then, in the remainder of the text, I will focus on three key aspects of Echaurren’s work in the 1970s: first, his geological/paleontological imaginary; second, the device of the grid; and finally, the distinctive temporal signature of the pre-1977 quadratini, which I will argue entails a politics even in the absence of obviously political iconography.

Strata of the Self

The quadratini adopt a consistent format: a grid of small rectangular cells, of many dimensions but most often six wide by nine tall, that somewhat resemble postage stamps or comic b ook panels. Their titles are sentences that the artist plucked at random from books or periodicals and which he generally inscribed in the lower right corner cell, above the signature and date.5 Although Echaurren would later go on to produce graphic novels,6 the association with comics is somewhat misleading here inasmuch as the quadratini never present a linear narrative. To read them sequentially from left to right and top to bottom is to miss their character as decentered matrices in which the relation of any one panel to its neighbors remains open-ended. There is rarely any clear indication that a specific panel represents a “before” or “after” with respect to another. These pictures are not devoid of events, however. Indeed, the quadratini teem with erupting volcanoes, mutating prehistoric lifeforms, and orbiting celestial bodies, as

2 Hoberman 2012.

3 On the early politics of Art Povera, see Galimberti 2013 and Cullinan 2008. Echaurren had only glancing contact with Arte Povera: he knew and discussed motorcycles with Pino Pascali (one of the few members of the loosely defined movement based in Rome rather than northern Italy) and saw important exhibitions such as Jannis Kounellis’s Untitled (Horses) at Galleria L’Attico in 1969, but was never close to the Turin-based group (personal communication, June 2022).

4 Nochlin 1989.

5 In Echaurren’s archive in Rome, there are several notebooks that consist solely of lists of these titles. These notebooks have not been catalogued or digitized.

6 The first of which was Caffeina d’Europa (Caffeine of Europe), an illustrated biography of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the leader of the Futurist movement (Echaurren 1988).

1. Nanni Balestrini, La violenza illustrata (Illustrated violence), Turin 1976, cover illustration by Pablo Echaurren

2. Pablo Echaurren, Nubi blu, gialle e nubi rosse (Blue, yellow clouds, red clouds), 1973, ink and watercolor on paper, 24 x 18 cm

well as more explicitly political vignettes of red flags and raised fists, as in the drawing used for the cover of Nanni Balestrini’s 1976 book La violenza illustrata (Illustrated violence) (fig. 1). A thematic inventory of the series would thus reveal what seems to be an odd conglomeration of extremely disparate imagery. The temporality of politics – in which decisive intervention at specific moments is crucial – butts up against the all-but measureless time of geology and astronomy. Evolution confronts revolution. In some instances, Echaurren directly superimposes these temporalities, as when hammers and sickles precipitate out of cityscapes, geological formations, and orbiting celestial bodies, as if communism itself were an emergent phenomenon within the cosmic order (fig. 2).7

7 Beginning in the early 19 60s, the Roman artist Franco Angeli (1935–1988), with whom Echaurren was acquainted, produced a series of paintings in which hammers and sickles share an allover pictorial field with five-pointed stars, perhaps suggesting a similarly cosmic diffusion of communist politics. Swastikas were to join Angeli’s visual repertoire as well (as they did in Echaurren’s work during the 1970s, symbolizing the ideological extremes of the “Years of Lead”).

“short circuit,” figuratively meaning a stress-caused yielding. In the story, Echaurren’s version of Corto Maltese enters the realm of comics bringing Paul Gauguin’s Tahitians and setting them free from the prison of painting. It is impossible not to interpret this brief story as an echo of Echaurren’s reflections on how comics can save and revitalize art, put it in contact with people, rescue it from the paralysis in which it is sometimes forced, in his opinion, by the artistic ambience.

Echaurren also included Futurist symbolism in his comics, beginning with a homage to the Futurist author and artist Maria Ginanni and her collection of lyrical writings Montagne trasparenti (Transparent mountains) (1917), in the short story “Maialini” (Little pigs) (fig. 7). This story of an erotic dream begins with a mountain with eyes that references the cover of Ginanni’s book (fig. 8) and a stylized figure of a pig, which, in turn, is a homage to the collab oration between the Russian Futurist artist and philosopher Aleksei Kruchenykh and Zina V., “an 11-year-old kid who was given by the artist the task to write a few compositions: an anecdote on a philosopher, a tale about three little pigs in a pocket, and a surreal dream.”70 Other references to Futurist imagery emerge from works such as “Notturni” (Alter Alter, no. 39, 1985) and “Tatto” (Comic Art, no. 34, 1987), with the recurring element of the eye descending from the prints of Futurist Guglielmo Sansoni, aka Tato (fig. 11). The former, subtitled “Kubofumetto,” mixes together comics editing through the simultaneous and prismatic combination of elements, which is typical of Cubism, and the recurrence of Tato’s trademark, a decontextualized human eye looking in different directions. The latter, the first-person narration of a fetishist man as he touches a woman’s clothing, intentionally equivocates the title “Tatto” (touch) with Sansoni’s nom de plume Tato, likewise referenced through an eye placed in the title’s graphics.71

7. Pablo Echaurren, panel from the short story “Maialini” (Little pigs), in Saette, supplement to Frigidaire, no. 56, 1985

After the initial enthusiasm toward auteur comics magazines, understood as a way to disseminate his artistic vision and his interest in breaking the rules of art, Echaurren realized that comics is not just a form of expression but a whole environment, with its own rules and celebrities. If in the first pages of Echaurren’s diary we read that “comics can take you anywhere” and that they represent an antidote to “gallery art” and “academic art,” the disappointment toward graphic narratives progressively took hold. As seen earlier, in the final pages of his noteb ook, the artist bitterly defines comics as “Cinderella art,” full of “shitty illustrators.” Nevertheless, he would never abandon this language: for example, in the later project Iconoclasta (1997) he makes collages using cuts from Futurist magazines paired with mainstream comics such as Disney and Looney Tunes and auteur comics like Peanuts. This practice responds to an equalizing and irreverent vision, interested in weakening anything that can be seen as an expression of power. Even in the most recent painting production (2010s), the artist resorted to conventional elements of mainstream comics such as balloons, grids, kinetic symbols, exclamation marks, and so on: once more, he indicates a trait of continuity between painting and comics, this time positioning himself not in the comics tradition but in the artistic one. Echaurren’s relationship with comics can therefore be defined as ambivalent: a clear fascination with its potential and a hostile skepticism toward the rules that lay beneath it.72 This evolution is extremely consistent for an artist who despises conformism, in comics as much as in art.

70 Echaurren 1982, p. 15.

71 Tato’s prints are part of the Futurist magazine collection of Fondazione Echaurren

2012.

72 Vacchelli 2022.

8. Maria Ginanni, Montagne trasparenti (Transparent mountains) cover design by Arnaldo Ginna, Florence 1917

Salaris. See Salaris

10. Pablo Echaurren, Teppista (Hooligan), 1988, watercolor and India ink on paper, 40 x 29.5 cm

11. Pablo Echaurren, Matite (Pencils), 1988, watercolor and India ink on paper, 48 x 33 cm

9. Pablo Echaurren, Oltre (Beyond), 1989, watercolor and India ink on paper, 40 x 30 cm

throughout Rome (fig. 1): a nod to the guerrilla actions of the BMPT group (Buren, Mosset, Parmentier, and Toroni) through the streets of Paris in 1967 and 1968. These actions were likely inspired by theories of the Situationist International founded in 1957, which saw art institutions as dead and invented “imaginative situations and poetic actions” to counter “capitalism’s spectacularization of day-to-day reality.”11 Echaurren was influenced by Marxist criticism of social alienation contained in two of his main Situationist references, both published in 1967: Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle, which condemned capital’s enforcement of cultural homogenization, and Raoul Vaneigem’s The Revolution of Everyday Life. Echaurren’s work often alludes to Situationist actions’ conscious lack of freedom in their attempt to subvert the system, as illustrated by Vaneigem’s prescient metaphor that “pissing on the altar is still a way of paying homage to the Church.”

In developing his personal iconography, the artist relied on the creative strategies of the movement such as détournement and derive in his countercultural work of the late 1970s, and subsequently as a basis for his collaboration with prisoners and former convicts in the 1990s. Echaurren’s workshops valued participation and human relations as a way of resisting social formatting, even though his work with neofascists, who were seen as the cockroaches of society, was part of a wider operation based on happenstance and friendships developed within the concentrationary universe of Rebibbia. These affinities evolved with both “high-profile” criminals as well as common detainees, such as the infamous “Canaro della Magliana” (Pietro De Negri), immortalized in Matteo Garrone’s 2018 feature film Dogman. Thus, Echaurren did not set out to collab orate with former right-wing terrorists, but ended up working with criminals from all backgrounds, some of whose ideologies were far removed from his own political ideas. His workshops were based on a philosophy of détournement, in the mental and psychological search for freedom from systemic repression.

For the Corrispondenze project, Echaurren collaborated with Curcio and Zatta to connect artists from the “free world” with prisoners at Rebibbia as well as with psychiatric patients from hospitals in Naples and Mantua. In the spirit of a (less secretive) Surrealist “exquisite corpse,” an artist and an inpatient or a prisoner would complete each other’s works of art on A3 sheets by sending them to each other in the post. The term corrispondenze implied relations between objects, people, or abstract ideas, as well as epistolary exchange. The works were then displayed in an exhibition that traveled from Arezzo to Rome to Città di Castello between 1994 and 1995.12 The objective of the exhibition, which related artisti affermati and artisti fermati (well-known artists and artists under arrest / who have been stopped), was to associate art made

11 Sholette 2010, p. 146.

12 Corrispondenze 1994.

1. Photograph by Massimo Bassinetti/AGF captioned “Young people fixing posters by Curcio and Echaurren, underground stories in rhyme and color: an invitation, the authors explain, to lift your eyes, look around, exit the subterranean solitude. A proposal of optimism,” published in Antonella Barina, “Curcio nel metrò,” il venerdì di Repubblica, January 28, 1994, pp. 38–42 (p. 42)

2. Pablo Echaurren and Claudio Piunti, poster for the Corrispondenze exhibition by Cooperativa LiberaMente & Sensibili alle foglie, 1994 (?), pen on cardboard, 35 x 25 cm. Private collection

in freedom with art made in confinement and to break down the social barriers of what the curators called the “ghettos” of society (fig. 2).

A number of the artists contacted refused or resisted the invitation; those who ended up collaborating included Enrico Castellani, Gianfranco Baruchello, Elisa Montessori, Piero Gilardi, and Nanni Balestrini, whom Echaurren knew or shared political interests with. While the works may not have been ground-breaking as such, the idea behind Corrispondenze exposed the mechanisms of the art market and the socially discriminatory attitudes against prisoners and inpatients, building on what Michel Foucault had been deconstructing in Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. First published in 1975 and translated into Italian in 1976, Discipline and Punish showed how the prison was part of a larger “carceral system” that rules the way in which modern society is governed. Identifying with the radical left, Echaurren crossed entrenched political divides, sometimes provoking former comrades.13 This perspective had roots in the late 1970s, when radical left-wing thinkers broke out of conventional patterns and debated philosophers identified with the extreme right such as Martin Heidegger or Ernst Jünger. For example, Massimo Cacciari and Gianni Vattimo wrote on the philosophies of Friedrich Nietzsche or Heidegger, while Giacomo Marramao and Mario Tronti on Carl Schmitt.14 Furthermore, in the early 1980s, within the Nuova Destra Italiana (the Italian New Right), Marco Tarchi organized conferences with the participation of Cacciari and Marramao. Within the attempt to overcome the opposition of left and right in the 1970s, certain extreme right-wing groups developed a strategy of so-called “Nazi-Maoism,” suggesting an unlikely united front against capitalism. Reflecting aspects of these ideas, the bookshop Stampa Alternativa offered an unusual spectrum of readings, from Echaurren’s anti-capitalist “bibles” such as The Society of the Spectacle to a rich selection of fanzines and the complete works of Nietzsche and Louis-Ferdinand Céline, one of Echaurren’s favorite authors, who had been identified with the French far right.

3. Gattabuismo. Futurismo, Dadaismo e Surrealismo visti da Rebibbia, exhibition catalog, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Rome, July 11– September 30, 1996 (Rome: Fratelli Palombi, 1996). The exhibition was organized by the Department of Cultural Policies of the Rome Municipality in collaboration with Arci Solidarietà – Ora d’Aria

As Alberto Toscano observes in his book Fanaticism. On the Uses of an Idea (2010), “non-linear and non-deterministic visions of politics are not alien to the Marxist canon.”15 I use Toscano’s original interpretation of the term “fanaticism” in relation to extremism and radicalism to indicate that which is at the very heart of politics and which results from the failure to formulate an adequate emancipatory politics. By the 1990s, Echaurren’s eclectic, open-minded, and non-judgmental philosophy led him to collaborate with, and at times befriend, former terrorists who were despised, feared, and stigmatized across the nation. His work with the “outliers” can be read within his drive toward all things outside of the mainstream – a theme that emerges in exhibition titles and articles about the artist, with curators and journalists often recurring to puns and catch phrases such as “off the page,” “out of place,” “unscheduled,” “a dissenting voice,” “an iconoclast” or “inconvenient.”16

As he did with Sensibili alle foglie, Echaurren introduced the avant-gardes to convicts offering them ceramics, painting, and collage workshops. Many of the works produced in the workshops that Echaurren led from 1995 to 1998 have never been published or exhibited and are kept in the Fondazione Echaurren Salaris archives; a large number of them are co-signed with Valerio Fioravanti. However, some of the works on paper were displayed in the exhibition Gattabuismo, staged at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome in 1996 (fig. 3). The artist’s experiment operated across various

13 For a description of Echaurren’s political perspective, see Marconi 1996.

14 Vattimo 1978, Cacciari 1978, Duso 1981.

15 Toscano 2010, p. 244.

16 In Apparati Storico-critici, Collezione Archivio della Fondazione Echaurren Salaris: “fuori pagina,” “fuori luogo,” “fuori programma,” “fuori quadro,” “fuori dal coro,” “fuori trincea,” “iconoclasta,” “scomodo.”

was activated in various ways, including the interpretation of dreams and the study of the natural world. It was through these activities that one accessed “the marvelous”: arresting and paradoxical elements that could catalyze new forms of thought. To imagine a new future, the Surrealists often looked not to the modern world and its progresses, but rather back in time. They admired the earlier approaches of German Romanticism and maintained an interest in evolutionary discoveries – topics that have also consistently attracted Echaurren’s attention.2

The comparison with Surrealism may seem startling at first, for Echaurren has a somewhat vexed relationship with the movement. He is the son of Chilean artist Roberto Sebastián Matta, who promoted Surrealist thought and techniques when he

1. Pablo Echaurren, Sulle tracce di una Limenitis anonyma (On the trail of a Limenitis anonyma), 1975, watercolor and India ink on paper, 24 x 18 cm

2 On the relationship between Surrealism and German Romanticism, see Von Maur 1991, Parkinson 2009, and Roberts 2016.

moved to Rome shortly after the end of World War II.3 Echaurren, however, has consistently distanced himself from his father’s activities or influence, choosing to trace his artistic lineage to Marcel Duchamp.4 Indeed, the elder French artist has been a formative figure for Echaurren, who discovered his work thanks to Italian artist Gianfranco Baruchello. Nevertheless, Echaurren’s practice exceeds a strictly Duchampian frame of reference, particularly in its attitude toward the natural world and evolution, which, I argue, shares affinities with Surrealist ideas.

While scholars have amply analyzed the artist’s Duchampian approach,5 the extent of his connections to Surrealism remains largely unprobed. Echaurren’s relatedness to the movement extended well beyond his father’s proximity to the group. Growing up, he had works by Surrealist artists Victor Brauner and Joan Miró in his bedroom; later, in the early 1970s, he signed a contract with Arturo Schwarz, the Milanese gallerist who promoted both Dada and Surrealism in Italy. Around that time, Echaurren also began corresponding with one of Surrealism’s most celebrated figures, Max Ernst.6 Describing his admiration for natural history manuals, Echaurren mentions “the little handbooks published by Martello, crammed with marvelous illustrations that would set my mind drifting in ways hard to describe.”7 While he does not mention Surrealism specifically, Echaurren’s comments echo the group’s fascination with nature as a creative catalyst.

In light of these personal associations and statements, Echaurren’s particular interest in and attitude toward the natural world and its origins acquire a new significance. The study of these convergences with Surrealism opens a novel angle from which to explore Echaurren’s practice, illuminating not only its strong coherence, but also a unique affinity with the movement based on a common pursuit of revolutionary creativity. Furthermore, the analysis of these parallel paths uncovers a new facet of Surrealism’s complex postwar legacy, enriching our understanding of the movement’s enduring relevance. Yet, to fully grasp the extent of Echaurren’s affinity with Surrealism, it is first necessary to examine the sociopolitical milieu within which he embraced these attitudes.

Resisting the Rigidity of Political Commitment

Coming of age in Italy during the 1970s, Echaurren witnessed an economic slowdown and an increasingly tense political climate. The previous decade was characterized by surging social unrest, which culminated in the large-scale student protests of 1968 and the so-called “Hot Autumn” of 1969, resulting in a wave of strikes in the country’s major industrial hubs. During this period, orthodox Marxism, emblematized by the Italian Communist Party (PC I), faced ideological challenges by some who perceived its agenda as too reformist and dogmatic. The period saw the rise of a series of militant groups known collectively as the extra-parliamentary left, who rebuked the representative democracy and traditional wage bargaining favored by the PCI. Playing a central role in the lab or unrest of the latter half of the 1960s, they attacked capitalist development, particularly the notion of productive work, through wildcat strikes and other disruptive tactics.8

Echaurren initially gravitated toward these ideological positions as he embraced Marxist theories and political praxis while working as an illustrator for Lotta Continua, a paper originally associated with the extra-parliamentary leftist group of the same name. The confrontational approaches that were characteristic of these militants soon

3 See Matta 2015; Larson 2022.

4 See, for instance, Echaurren 2019.

5 Perna 2016; De Chiara 2022. Echaurren’s correspondence with Max Ernst is housed in the Collezione Archivio della Fondazione Echaurren Salaris.

6 Salaris 2015b, pp. 229, 231.

7 Echaurren 2022, p. 59 (emphasis is mine). The Martello publishing house (Aldo Martello Editore) was founded in Milan in 1942.

8 Ginsborg 1990, pp. 298–347; Wright 2017.

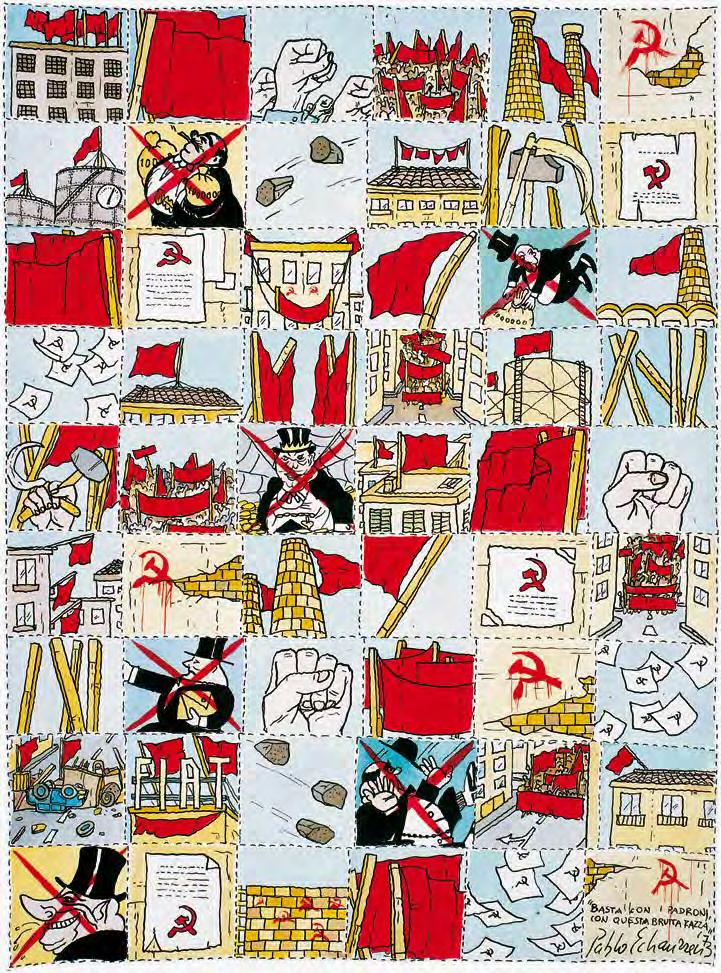

found their way into his quadratini, as Basta con i padroni, con questa brutta razza (Enough with the bosses, with this ugly breed) of 1973 clearly indicates (fig. 2). It depicts various scenes of protests, raised fists, projectile rocks, and an abundance of red flags and flyers with the communist hammer-and-sickle symbol. Six stereotypically plump capitalists are interspersed among these symbols of collective action, each crossed out with a large “X” to indicate their impending demise. With these elements, the work underscores the feelings of conviction and power experienced by members of the extra-parliamentary left at this time.

Another work completed in the same year and entitled La pietra di paragone (The touchstone) further illustrates the artist’s avowed engagement and the ways in which he understood Marxism and communist politics as the singular mold of worlds to come (fig. 3). The work consists of nine squares, each depicting rocks in configurations that resemble a hammer-and-sickle. Some arrangements appear man-made, such as the one placed upright in the leftmost corner of the work’s top register, or those that lie flat on the ground as in the first and third squares of the middle register. While these

2. Pablo Echaurren, Basta con i padroni, con questa brutta razza (Enough with the bosses, with this ugly breed), 1973, watercolor and India ink on paper, 24 x 18 cm

3. Pablo Echaurren, La pietra di paragone (The touchstone), 1973, India ink and enamel paint on paperboard, 24 x 19 cm

compositions look like carved statues, other formations appear to be naturally occurring, such as the outline of pebbles found at the center of the middle row, or the formation depicted in the rightmost square of the top register. The work’s title clarifies the purpose of these geological hammer-and-sickles in its reference to the pietra di paragone, or touchstone, which is a tool used to assess the purity or quality of precious metals. Here the touchstone is ideological, with communism presented as the standard measure of future social formations.

Yet this touchstone appeared increasingly restrictive to Echaurren, who found his editors’ appeal for legible ideological imagery more and more stifling. In addition, violence and terrorism were on the rise within extra-parliamentary circles as some of these groups embraced armed struggle in the pursuit of revolution. Feeling cornered in this oppressive climate, Echaurren turned to different creative outlets, aligning himself most notably with the Indiani Metropolitani (Metropolitan Indians) counterculture group in 1977. Looking to avant-garde strategies of disruption, chance, and imagination inherited from Dada and Surrealism and recently taken up by organizations like the Situationist International, the Indiani Metropolitani produced zines populated by fantastical monsters and animals as well as ironic interventions and happenings. With their activities, they countered capitalism’s work ethic of productivity, the rigidity of both mainstream and extra-parliamentary leftist activism, and the perceived ossification of social structures.9 In so doing, the Indiani Metropolitani participated in a broader international, postwar countercultural reception of Surrealism. As Abigail Susik has argued, a constellation of leftist activists across Europe and the United States in the 19 60s and 1970s looked to Surrealism for “a series of protest strategies and paradigms for dissidence in the present.”10

Echaurren’s Surrealizing pursuit of creative liberation exceeded his association with the Indiani Metropolitani, informing his individual aesthetic practice tout court. Indeed, as he was producing his quadratini in the 1970s, Echaurren began corresponding with the famed Surrealist master Max Ernst. Since his days as a Dadaist in Cologne, Germany during World War I, Ernst had been combining chance and authorial action to create arresting images that quickly resonated with Breton and his circle. He continued to explore these concerns while exiled in the United States during World War II and following his return to France in the mid-1950s, until his death in 1976.

Beginning in 1971, Echaurren sent his older German colleague one small painted square every month for a total of nine months, so that after this period of gestation Ernst possessed a full quadratino. For his part, Ernst responded regularly acknowledging receipt of Echaurren’s works, which he likened to a series he made between 1946 and 1953.11 Titled “microbes,” these tiny pieces were produced while Ernst was in the southwestern United States. They combine two of his processual hallmarks: automatic techniques (in this case decalcomania, a transfer procedure whereby wet pigment is placed on a surface covered with a material that when removed leaves a particular pattern or residue) and intentional mark making.12 Ernst was correct to note similarities between Echaurren’s practice and his own, from the small format to the ways in which the younger artist’s process frustrated predetermined meaning. Yet the parallels do not

9 Perna 2016.

10 Susik 2021a, p. 3 81.

11 As attested by a letter kept at the Collezione Archivio della Fondazione Echaurren Salaris and reprinted in Contropittura 2015, p. 14.

12 See Johnson 2019.

popular science book La terre avant le deluge, published by Louis Figuier in 1863 as a creationist response to Darwin’s The Origin of Species 36

With the automatic technique of frottage, Ernst created a new inventory of fossilized life forms, such as the dragonfly found in Les éclairs au dessous de quatorze ans (Teenage lightning) (fig. 15). This insect, which featured prominently in Figuier’s book, is depicted downward, humming above the sea, its wing texture rendered by the frottage of a leaf. The rubbing that produces the sea at the bottom of the composition, as Ralph Ubl has noted, appears in other prints as fossilized plant bark.37 As a result, a new natural history comprised of fictitious fossils emerges that parodies the “modern catechism” of Figuier 38 For Ubl, these images, engendered by Surrealist automatist techniques like frottage and made “from the perspective of revolutionaries who want to start ‘our education’ again,” have radical stakes.39 They contribute to Surrealism’s broader aim of subverting conventional narratives derived from rational thought by proposing a new natural history unearthed from the depths of the subconscious through frottage.

More precisely, Ernst’s Histoire naturelle portfolio is an exercise in unlearning, along with his collages and overpaintings inspired by manuals and publications circulated as a response to and dissemination of Darwinist ideas. As such, these works function similarly to Echaurren’s Neander Tales assemblages, which also seek to overturn conventional narratives surrounding the legacy of the Neolithic revolution. In so doing, Echaurren proposes an alternative to received conceptual hierarchies by elevating the Neanderthal as the paradigmatic actor of prehistory. Unlike Ernst, Echaurren did not cite Figuier directly in his assemblages, though he was familiar with his work. “I read Louis Figuier, Marcel Roland, and Jean-Henri Fabre with the same enthusiasm as I followed the tales of Salgari,” he has remarked, likening Figuier and other natural science writers to the science fiction author Emilio Salgari.40 Ernst, too, was aware of early science fiction writing that sought to apply Darwin’s theories to questions regarding life

36 This connection was first advanced by Hans Holländer and has been recently reappraised by Ralph Ubl. See Ubl 2013, pp. 96–105.

37 Ubl 2013, p. 103.

38 Ibid., p. 105

39 Ibid., p. 105.

40 Echaurren 2022, p. 59.

15. Max Ernst, Les éclairs au-dessous de quatorze ans (Teenage lightning), in Histoire naturelle, 1926, collotype after frottage, 50 x 32.4 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

16. Max Ernst, Éve, la seule qui nous reste (Eve, the only one left to us), c. 1925, in Histoire naturelle, 1926, collotype after frottage, 49.8 × 32.3 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

on other planets. In particular, he knew the novels of Camille Flammarion, which were quite popular during his lifetime; one of them, La Fin du monde (translated in English as Omega: The Last Days of the World ) of 1894, was reprinted the year Ernst started work on Histoire naturelle to mark the death of its author. The story describes a deadly collision between Earth and a comet that almost effaces the human population. Only two characters, Omega and Eva, remain alive until they are transported to a new planet. Curiously, the last print of Histoire naturelle is entitled Éve, la seule qui nous reste (Eve, the only one left to us), and, according to Kort, should be understood in relation to Flammarion’s text (fig. 16). Furthermore, in her view, “the fragmented, irregular forms” of the fictitious fossilized world of Histoire naturelle “are close in spirit to the cataclysmic bent” of Flammarion’s texts.41 In addition to its associations with science fiction, Éve, la seule qui nous reste also calls to mind the biblical story of Adam and Eve, which is also, at its core, a tale about old and new worlds.

Echaurren integrated this narrative into one of his Neander Tales assemblages. Entitled The Stone without Sin (2020), this shadow box develops his meditation on the Neanderthal and comes to consider the question of original sin (fig. 17). According to the artist, Adam and Eve were Sapiens, and thus evolutionarily distinct from the Neanderthal. Consequently, the Neanderthal lacks original sin, something Echaurren emphasizes through the use of feathers, which signify lightness. Along the internal edges of the box, Echaurren has written, “And if Sapiens had lost the challenge?” and “Rethink Evolution.” Many years earlier, as Histoire naturelle attests, Ernst was grappling with similar issues, though his answers remained much more ambiguous.

Genetic Iconoclasm

Echaurren’s practice was not only informed by his heterodox leftist viewpoint, but also consistently animated by geology and prehistory, as the quadratino entitled Alla ricerca della pietra del paragone (Looking for the touchstone) produced in 1975 attests (fig. 18). This watercolor, which only features nine squares, zooms in on various rocky

41 Kort 2009, p. 45.

17. Pablo Echaurren,

The Stone without Sin, 2020, mixed media assemblage, 38.5 x 48.5 x 9 cm

playful systematization of early works and inscribed with explicit historical and temporal dimensions. With an emphasis on scientific systematization and serialization of archaic and modern object-forms, the b oxes expand the quadratini into a sculptural dimension as an encyclopedia of possibilities, a “mental diary” for self-analysis.16 The formal and material three-dimensional enlargement of the quadratini was already devised by Echaurren in some boxes produced in the same period such as Sono un triste pappagallo (I am a sad parrot), Minerali (Minerals) (fig. 1), and E lo schizoblasto? (What about the schizoblast?) from 1974. In these works, instances of “little squares” were juxtaposed by a repertoire of objets trouvés (garters, mineral crystals, fossils). Inspired by Gianfranco Baruchello’s boxes produced in the 1960s and 1970s, the

16 See Echaurren’s comments in De Finis, Echaurren 2020.

1. Pablo Echaurren, Minerali (Minerals), 1974, box, mixed media, multiple, III/VI, artist’s proof, 26.5 x 19 cm

2. Pablo Echaurren, A caccia di uova di dinosauro col binocolo (Hunting dinosaur eggs with binoculars), 1973, India ink and enamel paint on paperboard, 24 x 19 cm

arbitrary classificatory arrangement and the ironic scientific repertoire of natural and man-made collections of objects are symmetrically arranged within the grid structure of the boxes. They are reminiscent of the mineral galleries of geological museums, or the nineteenth- century Naturalienkabinet 17 Exploring thematic and formal affinities, the small squares of Riconoscersi nella terra (Identify oneself with the land) (1972) offer a primordial zero-degree landscape, evoking a return to a dehumanized temporality and geographical remoteness or alterity (fig. 5 on p. 158).18 Echaurren orchestrates an alignment of desert panoramas and litho-geological formations, weaving together mountains and caves within a fictitious and whimsical Monument Valley – ranging from the realm of Road Runner to Gian Luigi Bonelli’s Tex Willer. Here, the sandstone mesas metamorphose into phallic symbols, while stalactites resembling uvulas or clitorises sprout from caves.19 These imaginative landscapes bear a resonance with the naturalist imagination championed by Surrealists such as André Breton who, in L’Amour fou (1937), alludes to crystals, coral, grottoes, and natural phenomena that were emblematic of the Baroque compendium of natural “wonders,” characterized by their inherent ambiguity. These elements resonate as objective poetic archetypes within the realm of natural philosophy. Il proseguio dei lavori in corso (Continuation of the work under way) (1973) then unveils a succession of lithic fantasies that appear to draw inspiration from both Hanna-Barbera’s Flintstones and the Surreal landscapes conceived by Max Ernst like Stratified Rocks, Nature’s Gift of Gneiss Lava Iceland Moss… (1920) (fig. 14 on p. 167), Sambesiland, and Paysage à mon goût (Landscape for my taste) (1921). In Di giorno in giorno (From day to day) (1974), Echaurren’s fascination with paleontological discoveries and remnants finds expression in a series of decomposed prehistoric animal fossils meticulously arranged in an arbitrary catalog. These enigmatic specimens are juxtaposed, their indecipherable nature making them parts of an imaginary taxonomic family or remnants of a fossilized modern bestiary In I lavori della famiglia Yu-King procedono a ritmo incessante (The work of the Yu-King family is proceeding at a relentless pace) (1975), monumental lithic art structures are pieced together in what appears to be a geological bricolage, creating a peculiar interplay of dimensions. This interplay underscores the contrast between the presumed size of these structures and the smallness of the squares, as well as the temporal incongruity between the ceaseless pace of modern artistic production and the vast expanse of geological eras. A caccia di uova di dinosauro col binocolo (Huntings dinosaur eggs with binoculars) (1973) parodies unattainable paleontological research, where deep time requires enhancing scopic technologies that allow neither investigation nor conceptualization (fig. 2).20

17 Contropittura 2015, pp. 60–62.

18 It is replicated in Pablo di Neanderthal after the opening titles, as if in a dream: Matarazzo 2022, 03:17.

19 Contropittura 2015, p. 45. A repertoire of stalactites, archaic and modern, returns in Neander Tales, in the box Stalagmyth–Bruniquel Tel Quel, with reference to the “prehistoric evidence found in the French cave of Bruniquel, where mysterious circular structures have been discovered that were made around 175,000 years ago with broken stalagmites.” Neander Tales 2022, pp. 104–105.

20 Contropittura 2015, p. 46.

Pablo Echaurren and Claudia Salaris on Avant-garde Collectivity

Interview by Ara H. Merjian, January 10, 2023

Ara H. Merjian In light of the centrality of collaboration and the collective nature of your work, Pablo, how might we characterize your personal relationship with Claudia? Might we speak of a collective of two?

Pablo Echaurren I was born into a fairly complex family, so in my case the family never provided the shelter necessary for growth and development. When I was about 17, I met a painter called Gianfranco Baruchello. I liked his paintings in a rather unexpected way; that is, I was not an art lover, even though in my home there were artworks hanging on the walls, some of them important. All the same, art didn’t really interest me. When I saw Baruchello’s works, small pictures with neat lettering, I thought they looked a bit like insect boxes; indeed, I wanted to become an entomologist as a kid, so I used to fill boxes with beetles and butterflies. The meeting with Baruchello – he was 43, I was 17 – changed my life, it was the meeting with a “new” father, who would teach me everything: how to drink a glass of wine, how to look at a painting, read a book, learn about a type of art that was unknown to me, the cerebral art of Marcel Duchamp, a friend of his. At that moment I literally swapped family tree: I chose Baruchello’s. The man who died four days ago at the age of 98. Claudia and I, on the other hand, met in 1977 (actually we knew each other before then), in a heated moment, it was the time of social conflicts and student protests.

Claudia Salaris I ran into Pablo at a demonstration in Rome, we had known each other since childhood. As a teenager he rode around on a motorcycle with a mop-top like the Beatles and wore flashy flowery shirts – I remember a Pop Art shirt, made with the English flag. His family and friends called him “Paino.” When we got together, we published a booklet on the issues raised by the protest movement and we signed it using our first names only, “Claudia and Paino.”

PE She was a real beauty, I was a cockroach. Yet she chose me, she accepted me. We have lived together since September 1977 and have never traveled separately, except in emergencies. We are one. From the very beginning, this union was an existential stance: when I was part of the Indiani Metropolitani, one of the things we used to write on walls was “Claudia Oh!” – a sort of invitation to side with love and oppose the violence surrounding us. Seeing “Claudia Oh!” next to slogans praising and spurring direct confrontation created a nice contradiction.

Cover Pablo Echaurren, Tra quarantatrè secondi circa (In about forty-three seconds), 1975, watercolor and India ink on paper, 24 x 18 cm p. 6

Detail of the announcement of Pablo Echaurren’s solo exhibition, Galleria Giulia, Rome, November 6 – December 12, 1984

Silvana Editoriale

Chief Executive

Michele Pizzi

Editorial Director

Sergio Di Stefano

Art Director

Giacomo Merli

Editorial Coordination

Maria Chiara Tulli

Copy-editor

Emanuela Di Lallo

Layout Serena Parini

Production Coordinator Antonio Micelli

Editorial Assistant Giulia Mercanti

Photo Editor Barbara Miccolupi

Press Office

Alessandra Olivari, press@silvanaeditoriale.it

All reproduction and translation rights reserved for all countries

© 2025 Silvana Editoriale S.p.A., Cinisello Balsamo, Milano

© Pablo Echaurren, by SIAE 2025

© Max Ernst, by SIAE 2025

© Succession Picasso, by SIAE 2025 © Raoul Ubac, by SIAE 2025

Under copyright and civil law this volume cannot be reproduced, wholly or in part, in any form, original or derived, or by any means: print, electronic, digital, mechanical, including photocopy, microfilm, film or any other medium, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Available through ARTBOOK | D.A.P.

155 Sixth Avenue, 2nd Floor, New York, N.Y. 10013

Tel: (212) 627-1999

Fax: (212) 627-9484

Silvana Editoriale S.p.A. via dei Lavoratori, 78 20092 Cinisello Balsamo, Milano tel. 02 453 951 01 www.silvanaeditoriale.it

Reproductions, printing and binding in Italy

Printed by Grafiche Peruzzo, Mestrino (PD) in January 2025

p. 6: Courtesy Tristan Weddigen p. 8: Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris

Portesine

1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10: Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris

3, 7: Mart – Museo di arte moderna e contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto

Spaulding

1: Book cover, Nanni Balestrini. Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris

2–10: Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris

Perna

1: Photo credit Tano D’Amico. Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris

2: Book cover, Marco Lombardo

Radice and Lidia Ravera. Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris

3 , 5–7: Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris

8: Photo credit Tano D’Amico. Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris 9, 10: Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris

Griffiths

1–5: Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris

6: Mart – Museo di arte moderna e contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto

Vacchelli

1: Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris

2: Image credit Scott McCloud

3: Mrs Gilbert W. Chapman Fund. © Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

4–11: Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris

Spampinato

1: Courtesy Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Rome

2–12: Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris

Caruso

1: Photo credit Massimo Bassinetti/ AGF. Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris

2: Courtesy Private collection

3: Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris

4–5: Photo credit Tano D’Amico. Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris

6: Photographer unknown. Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris

7: Elaborazioni Fotografiche OMEGA. Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris

Galimberti

1–13: Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris

Antonucci

1–6, 9–13, 17–20: Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris

7–8: Image credit bpk/CNAC-MNAM/ Raoul Ubac

14–16: Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence Antonello

1–12: Courtesy Fondazione Echaurren Salaris

Photo credits