Chris

Dähne

Helge Svenshon

Martin

Mäntele

Chris

Dähne

Helge Svenshon

Martin

Mäntele

Eds.

56 Max Bill – Aspects of Bauhaus

Reception in the Early Years of the HfG Ulm

Martin Mäntele

66 The Next Experiment

Konrad Wachsmann’s Armco Curtain

Wall Project alongside Teaching at the HfG Ulm, 1955–57

Soetje Beermann

75 Rethinking Design

The Internationalisation and Scientification of Architecture

Teaching at the HfG Ulm

Chris Dähne

88 Giuseppe Ciribini at the Crossroads

Post-war Italy, the HfG Ulm, and the Architecture-Building Industrialisation Nexus

Francesco Maranelli, Pierfrancesco Califano

“Integral – Universal – Industrial”

Herbert Ohl’s Concepts for Industrialised Building at the HfG Ulm

Helge Svenshon 112 Prefabricated Welfare

Herbert Ohl’s Urban Development System for Saarlouis-Beaumarais Joaquín Medina Warmburg 127 Institut de l’Environnement –A Radical Reinterpretation of the Ulm Model

Rafael Amato, Teresa Häußler

Architecture Studies at the HfG

The Enrolment Process

HfG Ulm Questionnaires

Reconstruction of the Curriculum

From the Foundation Course to Design Projects

Max Bill departs from the HfG following disagreements with younger faculty members over the school’s future direction

Lecturers and supervisors

Bruce Martin (1957–59)

Hanno Kesting (1957–60)

Anthony Frøshaug (1957–60)

Matthew Wallis (1957–59)

Horst Rittel (1957–63)

Joseph Ryckwert (1957–58)

Giulio Pizzetti (1957–60)

Christian Norberg-Schulz (1957–58)

Influential students

Günther Schmitz (1957–61)

Rupert Urban (1957–61)

Roland Lindner (1957–62)

Following the departure of Bill and Wachsmann, Herbert Ohl takes over as head of the department. With system-building projects such as the Integral Building Construction, he continues down the path set by Wachsmann. In this context, the name is changed from Architecture and Town Planning to Building Department, reflecting its new focus on construction processes.

Reform of the curriculum

Founding and publication of the first Ulm. Journal of the HfG. The editor was Dr. Hanno Kesting, October 1958. Fourteen issues of the Ulm journal were published between October 1958 and April 1968

Rectorship Tomás Maldonado

Otl Aicher Hanno Kesting

Nuclear energy

The Atomium, unveiled at the 1958 Brussels World Expo, symbolises the atomic age and scientific progress. Standing 102 meters tall, its nine spheres represent an iron crystal magnified 165 billion times, celebrating nuclear science’s transformative impact on the world.

Lecturers and supervisors

Christian Staub (1958–63)

Lucius Burckhardt (1958–59)

Frei Otto (1958–60)

Guiseppe Ciribini (1958–60)

Richard Buckminster Fuller (1958–59)

Influential students

Winfried Wurm (1958–62)

Hubert Matecki (1958–62)

Willi Ramstein (1958–62)

Leonhard Fünfschilling (1958–63)

Marcel Herbst (1958–64)

Karl Berthold (1958–63)

Invitation to São Paulo for the Congress The New City – A Synthesis of Arts

Miles Davis’ “Kind of Blue“ revolutionised jazz with the birth of modal jazz. Shifting from bebop’s complexity to soulful simplicity, its innovative approach inspired countless artists and cemented its status as a timeless masterpiece and cornerstone of modern music.

Reform of the curriculum by Maldonado, introducing scientific disciplines such as methodology, philosophy of science, topology, semiotics, etc.

Diploma thesis and successful competition entry achievement, Max Graf “Oberstufenschulhaus Pestalozzidorf“, Trogen, Switzerland, 1958–60, lecturer Max Bill see page 273, fig. 256–257

25 April, Charles Eames again visited the HfG. He presented three of his film experiments, which had received various awards.

Herbert Ohl

Horst Rittel

On 14 March, the philosopher Martin Heidegger and the architectural theorist and critic Reyner Banham visit the HfG.

Frei Otto lectures on Sinn und Aufgabe des Leichtbaus. Bericht über die Entwicklung von Bauten mit vorgespannten Membranen (The Meaning and Purpose of Lightweight Construction. Report on the Development of Buildings with Tensioned Membranes) and Die allgemeine Aufgabenstellung des Bauens in unserer heutigen Zeit. Die Probleme des anpassungsfähigen Bauens (The General Challenges of Building in Our Time. The Problems of Adaptive Building).

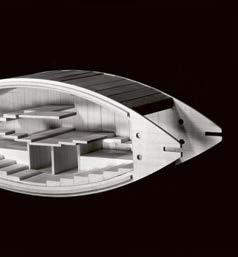

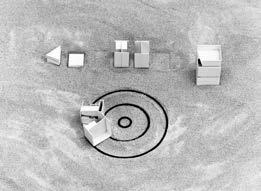

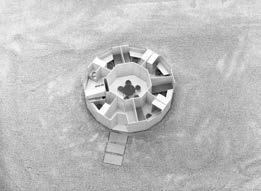

true to scale wooden model. Konrad Wachsmann and his team ultimately assembled a new, voluminous apparatus with sudden changes of direction, which was extensively photographed for documentation purposes.fig. 3

“Stützen wird man in Zukunft wohl anders als heute beurteilen. Sie werden fast völlig verschwinden, so dass wir sie schliesslich gar nicht mehr bemerken, selbst wenn sie da sind. Ebenso wird sich das, was wir uns unter Wänden, Fenstern und Türen vorstellen, beachtlich ändern. Ich könnte mir denken, dass nur Flächen existieren werden, undurchsichtige, durchsichtige und bewegliche,”43 or so Konrad Wachsmann predicted while working on his project in Ulm, during a lecture on “Bauen in unserer Zeit.”44 The wall construction system for Armco was intended to provide precisely such new surfaces and be able to form autonomous spatial structures. After hearing Wachsmann’s lecture, Stuttgart-based civil engineer and professor at the TH Stuttgart, Curt Siegel, accused his colleague of lacking a sense of reality in favour of a penchant for

“symbolic content”, and said he wanted to see some “definable […] substance”45 in the form of construction plans or scientific reports. By contrast, Wachsmann was entirely convinced of his work as the ideal step towards industrialised building. From his perspective, with his Ulm experimental model, he had created a “universal building method”46 for both indoor and outdoor applications, using standard parts that build upon each other.47 Based on a modular organisation, each chosen wall development (interior and exterior corners or undercuts) could be achieved using prefab moulded panels.48 Konrad Wachsmann’s curtain wall was only constructed once – and only for a trial period as a façade system for an office building in the USA.49 In his life-long search for rationalisation and standardisation measures in the field of architectural production, Wachsmann repeatedly underlying artisanal principles onto industrial applications. He invented special “fastening devices”50 and “adapters”51 – original elements that were intended to be able to solve any building task, depending on the context and through the addition of components. Also during his model construction studies on the “spinner”52 for the Ulm curtain wall in 1956, he managed to reconcile a pragmatic-artisanal approach and an intellectual strategy through the programmatic simplification of a building problem. However, some of the architectural ideas were on such a small scale and meticulously described by Wachsmann – right down to the specific step of “using the Allen key” – that he himself realised that required too much explanation as visual aids in his lectures to be presented in public. As the project progressed, Armco as a company also decided against mass production of the wall construction system due to its high level of complexity.53 After his first period at the HfG in 1955, Konrad Wachsmann had already been labelled by Max Bill as only “temporarily useful” due to his lack of practical relevance. Bill already assumed that, “bei wachsmann ein beträchtlicher teil mythos mitspielt.”54 The Ulm curtain wall therefore remained one of Wachsmann’s “Vision[en], […] vorgebracht als Denkmodell ohne Anspruch auf Ausschließlichkeit,”55 born of progressive “building thoughts” on “adaptable […] architecture”56 and a considerable portion of imagination. Konrad Wachsmann is regarded in architectural history as a pioneer in developing industrial production methods in the field of construction. His work on the Ulm curtain wall project combined his practical building experience both as an architect and a craftsman, contributing specialist theoretical hypotheses. He was also effective with the media – while not always without criticism from his contemporaries – in communicating his personal architectural concepts. The HfG offered Wachsmann both an actual and a theoretical space to test his building experiments on a 1:1 scale. The ability to autonomously produce prototypes for industrial production – including the acceptance of not always linear development processes and an added value going beyond purely economic profitability – became an element of architectural teaching in Ulm through Wachsmann’s teaching approach. In view of the heightening global challenges on

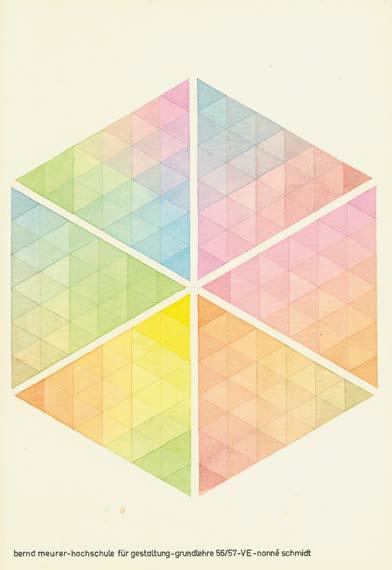

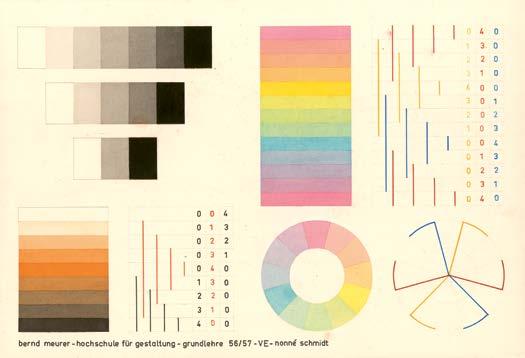

5 Colour theory according to Ostwald, lecturer Helene Nonné-Schmidt, student Bernd Meurer, 1956–57, 37.9 × 25.8

6 Colour theory according to Ostwald, lecturer Helene Nonné-Schmidt, student Bernd Meurer, 1956–57, 25.8 × 37.9 cm

Labinsch, 1967–68, 13 × 18 cm

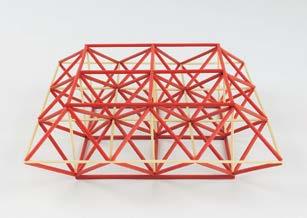

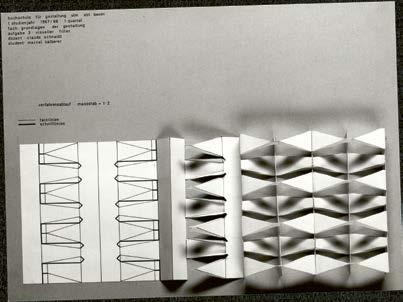

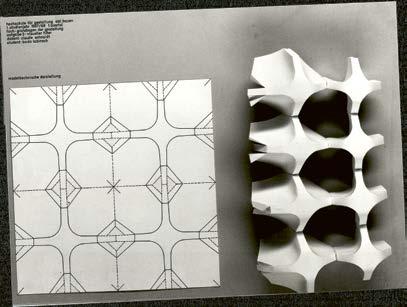

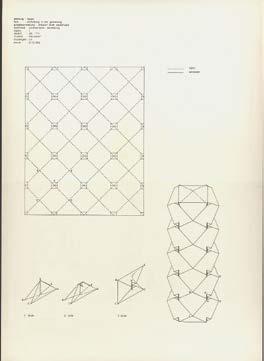

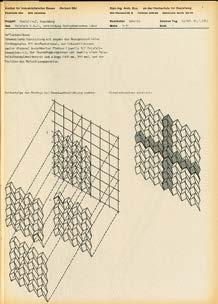

A flat grid was to be used to create a paper honeycomb by means of spatial deformation and contraction. The working material of paper or card was processed by folding, cutting, and gluing to create a honeycomb without any waste. The results comprised axonometric presentations of the previously processed material, as well as models of the completed honeycomb.

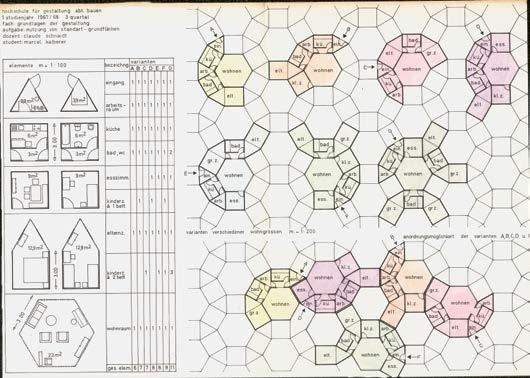

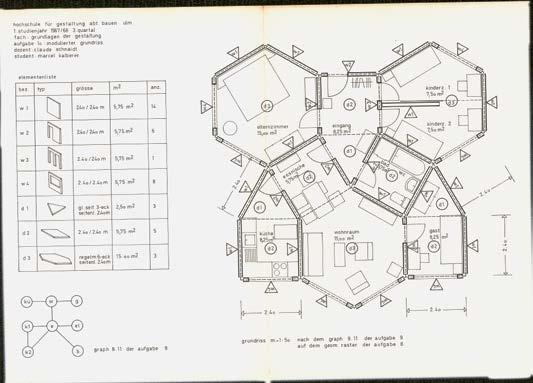

fig. 134 Utilisation of standard floor plans, lecturer Claude Schnaidt, student Marcel Kalberer, 1967–68, 29.7 × 42 cm

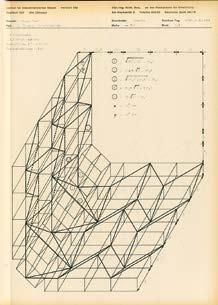

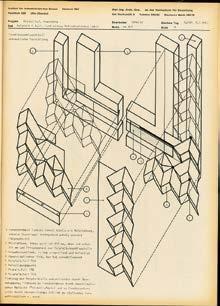

fig. 207–209 Hostalit-Z, application reception area FWH (IIB), part: gable cladding Polyfalt, Polyfalt edge, scale 1:2, cladding radiochemical laboratory, plate joint, scale 1:10 and window connection detail, scale 1:50, director Herbert Ohl, assistant Günther Schmitz, 1961–62, 29.2 × 21 cm (each)

fig. 210 Hostalit-Z, poly-folding panel system, connecting elements for room corners, lecturer Herbert Ohl, collaborators Bernd Meurer, Günther Schmitz, 1961–62, max. 90 × 29 × 18 cm

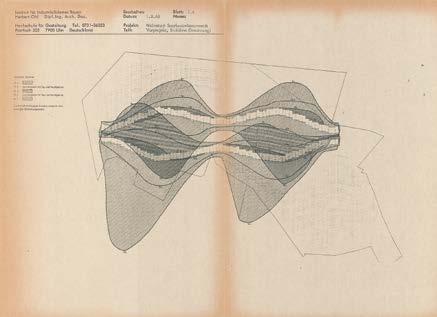

fig. 253 City housing in Saarlouis-Beaumarais (IIB) Part: preliminary design, bioclimate (sunlight exposure), lecturer Herbert Ohl, assistants Claude Schnaidt, Asano Tadatoshi, Hans Peter Goeggel, 1.8.1968, 30 × 42 cm

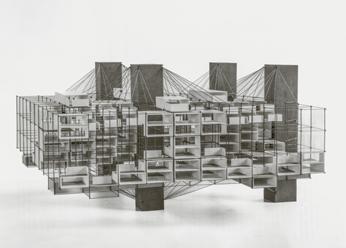

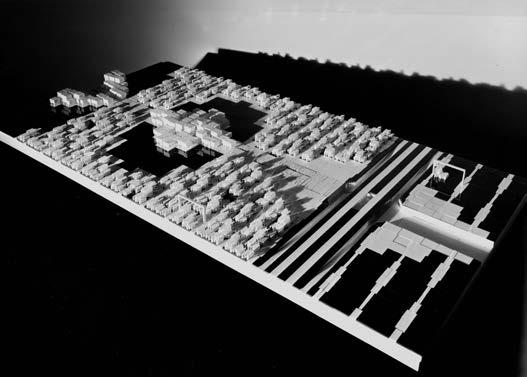

fig. 255 City housing in Saarlouis-Beaumarais (IIB), model study, lecturer Herbert Ohl, student N.N, 1968, 5 × 35 × 20 cm

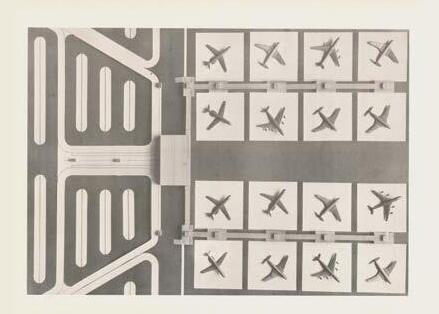

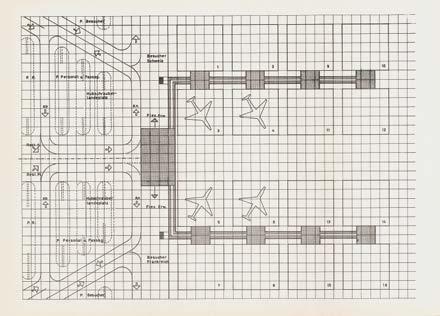

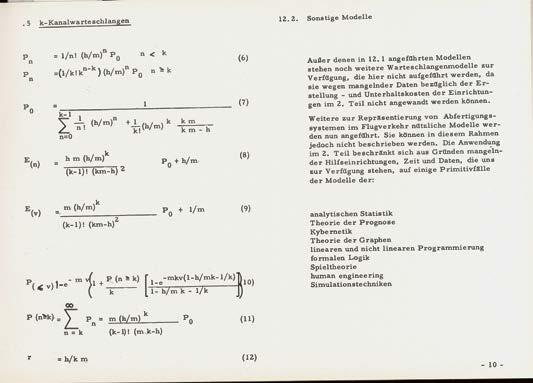

fig. 270–272 Planning a flexible airport, model view, floor plan, regional and local planning with mathematical models, lecturer Herbert Ohl, students Roland Lindner, Winfried Wurm, 1961, diploma thesis, 21 × 29.5 cm (each)

fig. 319–320 Building process, new insights: low-cost housing in developing countries, urban planning model, lecturer Herbert Ohl, Bernd Meurer, student Peter Ryffé, 1968, diploma thesis, photos 21 × 30 cm

This book traces the legacy of the HfG Ulm Building Department, where experimentation and intellectual rigor redefined modern architecture. Relying on critical enquiry and knowledge exchange, the department brought design, science, and creativity to bear in addressing architecture’s complex challenges. Today, Ulm’s open mindset feels more compelling than ever, reshaping how we inhabit and imagine the future of our data-driven world.

Georg Vrachliotis, Head of the Architecture Department, and Professor for Theory of Architecture and Digital Culture, TU Delft / Author of The New Technological Condition. Architecture and Design in the Age of Cybernetics