BY THE ARTIST; CARL GUSTAV CARUS; JOHANN WOLFGANG VON GOETHE AND HEINRICH MEYER; HEINRICH VON KLEIST, ACHIM VON ARNIM AND CLEMENS VON BRENTANO; GOTTHILF HEINRICH SCHUBERT; VASILY ANDREYEVICH ZHUKOWSKI

introduced by

JOHANNES GRAVE

Introduction

JOHANNES GRAVE

p. 9

From his early writings

p. 39

The Commandments of Art

CASPAR DAVID FRIEDRICH

p. 45

Reminiscences of Caspar David Friedrich

CARL GUSTAV CARUS

p. 53

From New German Religious-Patriotic Art

JOHANN WOLFGANG VON GOETHE AND HEINRICH MEYER

p. 79

Frontispiece (p. 2): Chalk Cliffs at Rügen, c. 1818

Opposite: Window with a View over a Park, c. 1810-11

Various sensations in front of The Monk by the Sea

HEINRICH VON KLEIST, ACHIM VON ARNIM AND CLEMENS VON BRENTANO

p. 85

Reminiscences of Friedrich GOTTHILF HEINRICH VON SCHUBERT

p. 99

Correspondence with the Russian Court VASILY ANDREYEVICH ZHUKOWSKI

p. 125

Note on texts and authors

p. 139

List of illustrations

p. 141

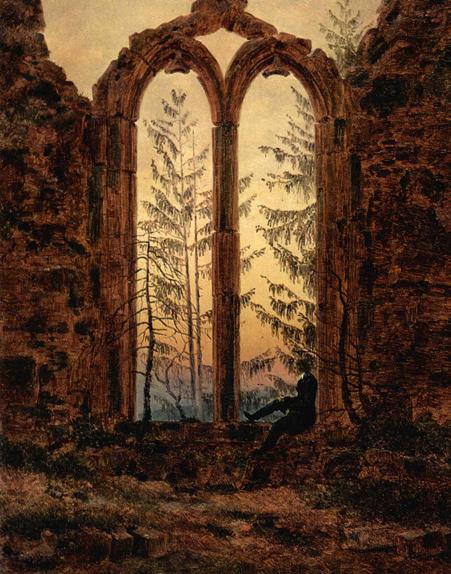

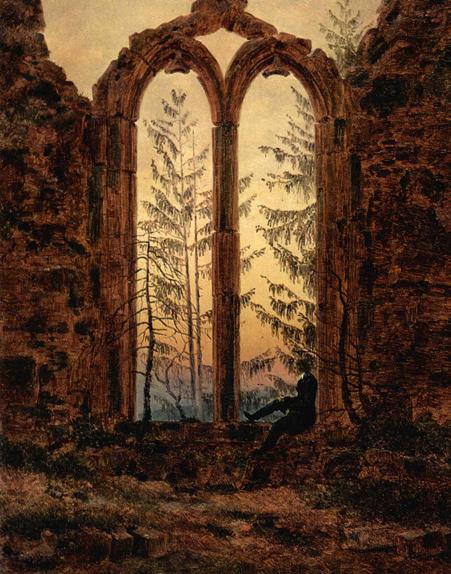

Opposite: The Ruins of Oybin Abbey (The Dreamer), c. 1835

It would be hard today to imagine a book or an exhibition on German Romanticism that did not include images by Caspar David Friedrich. Indeed, his works are often used as illustrations for other eras and aspects of German culture, history and society too. Tis applies in particular to Te Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog – a painting that is often seen as the ideal embodiment of German-ness, although in fact it only became known in the middle of the 20th century and no commentary on it by Friedrich himself or by contemporaries survives. Friedrich’s pictures have become a projection of supposedly typically German-ness – with all the ambivalences and problems that might imply. Exhibitions such as Te Romantic Spirit in German Art 1790–1990 (Edinburgh

Opposite: The Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, c. 1817-18

and London, 1994) or De l’Allemagne (Paris, 2013) have shown what the consequences of viewing Friedrich’s Romantic painting as the epicentre of German art might be. Especially from the perspective of European neighbours, Friedrich’s paintings are often seen as symbols of both the fascination and the abysmal nature of a German culture in which Romanticism and fascism seem to combine in an uncomfortable way. But – it must be said clearly – this idea of German culture is just as misleading as the image of Friedrich’s art on which it is based.

At first glance, there seems to be a lot to suggest a close connection between Friedrich’s art and Germany. His paintings, with very few exceptions (such as the imagined polar region of the Arctic Ocean) seem to be almost exclusively of German landscapes. More careful analysis, however, shows that the paintings are idiosyncratic representations of parts of Germany assembled by the painter in the studio: they are original compositions albeit based on very precise study drawings. While other ambitious artists of his time did everything they could to be able to spend longer periods in Italy in order to learn from the masterpieces of antiquity or the Renaissance and to experience ideal landscapes under a Mediterranean light with their own eyes, Friedrich decided against

Overleaf: Rocky ravine in the Elbe Sandstone Mountains, 1822-23

such a trip . Instead, his excursions and longer hikes took him to Saxon Switzerland, the Harz Mountains and the island of Rügen – areas that only subsequently came to be perceived as typically German landscapes. And last but not least, a few of Friedrich’s statements have come down to us in which he identified himself as an opponent of Napoleonic expansion and – there is no getting around this – as a hater of the French. In a letter dated 24 November 1808, he even asked his brother Christian, who was staying in Lyon, not to send him letters again until he had left French soil.

It is therefore not surprising that Friedrich and his work attracted particular interest during the Nazi era. At the beginning of the 20th century, at the Berlin Centenary Exhibition of 1906, he was rediscovered as a forerunner of the pioneering painting that was valued by precisely those progressive museum directors and art historians who were also committed to French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism: Hugo von Tschudi, Woldemar von Seidlitz, Alfred Lichtwark and Julius Meier-Graefe. But in the 1930s and particularly the 1940s, Friedrich had become the epitome of a German national artist. His Nordic landscapes and his statements against the French were used as an opportunity to see in

Opposite: The Chasseur in the Forest, c. 1813

him – as the Nazi sympathiser Kurt Karl Eberlein tried to do – the embodiment of ‘the old genetic heritage of the Germanic style’ and a ‘Nordic artistic spirit’. Books with reproductions of his works now found their way into the kitbags of German soldiers along with field editions and field libraries.

However, the Nazi appropriation was only possible at the price of considerable distortions. Friedrich’s deep, thoroughly Lutheran faith had to be pushed into the background, as did the fact that he had received his artistic training from 1794 to 1798 in Denmark, at the Copenhagen Academy, and that in later years he had had encounters with French artists like Pierre-Jean David d’Angers and Alphonse de Labroue. And in general, crossborder references were woven into Friedrich’s life from the very beginning. He came, after all, from Greifswald, a city in Western Pomerania that, though still part of the Holy Roman Empire, was ruled by the King of Sweden.

Tere are no decidedly ethnic ideas to be found in Friedrich’s surviving writings, nor are there any explicitly anti-Semitic statements. If he showed an aversion to France during the years of the Napoleonic occupation and the wars of liberation, this attitude did not necessarily have to be national-patriotic in a chauvinistic sense – especially since a German nation state was hardly conceivable, especially in the early 19th century. Some

poems he wrote in 1813/14 suggest that he interpreted Napoleonic foreign rule and the defeat of France in religious terms and saw it as a kind of divine judgment. Confessional questions, i.e. the defense of Protestantism, could have been at least as important for Friedrich as a German national feeling. It is therefore in fact quite possible that Friedrich was not interested in genuinely German landscapes when he integrated motifs from Saxony, Bohemia, Mecklenburg or the island of Rügen into his paintings. Te fact that he did not paint classic Mediterranean ideal landscapes can also be explained by his way of working. It required being very familiar with nature, which would provide the basis for his pictures. Troughout his life, Friedrich accumulated a large collection of detailed drawings of nature studies that accurately reproduced particular trees, plants, rocks, with all their individual peculiarities. He continually referred to these drawings when working on his paintings. While he generally transferred the individual natural motifs remarkably faithfully into the picture, their composition deviated from the real models. In the oil paintings, a tree drawn in Neubrandenburg could be relocated to the Baltic Sea, or the Eldena monastery ruins near the sea could be surrounded by the Giant Mountains of Bohemia. Te concentration on landscapes that were later seen as typically German,

is explained not least by the extremely high importance that Friedrich attached to the detailed study of nature. However, the pictures that were created do not show real German areas, but rather compositions that were very consciously calculated by the artist.

Although Friedrich gave lessons to a number of young painters, he never founded a school in the true sense. August Heinrich, Ernst Ferdinand Oehme, Carl Gustav Carus and a few other artists at times oriented themselves explicitly on Friedrich’s works, but even in Dresden there were painters, for example Gustav Heinrich Naeke, Carl Gottlob Peschel and Ludwig Richter, who represented significantly different strands of Romanticism. Tis applies even in the larger German perspective. Although Philipp Otto Runge was known to and probably friends with Friedrich, his conceptually highly sophisticated paintings decorated with meaningful figures and allegories are very different from Friedrich’s work. Te paintings of the Nazarenes and the Düsseldorf school had greater impact and were more influential than those of either Runge or Friedrich. Altogether it would be misleading to consider Friedrich to be a particularly typical representative of Romantic painting in

Previous pages: The Ruins of Eldena in the Giant Mountains, 1830-34

Opposite: The Ruins of Eldena Abbey, 1814

Germany. Indeed, from the 1820s onwards, his contemporaries saw him as more of an outsider.

If Friedrich’s work does not represent the centre of German Romanticism, it is even less obvious how one might understand him as part of a comprehensive European Romanticism. Nothing seems to connect him with painters such as Téodore Gericault or Eugène Delacroix, let alone with Francesco Hayez or Francisco de Goya (insofar as one can characterize parts of the latter’s œuvre as romantic). Even the path from Friedrich’s landscapes to the pictures of J. M. W. Turner or John Constable seems very long. It is therefore not surprising that few art historians have attempted to describe European Romanticism as a movement with overarching characteristics. To the extent that the boundaries of a purely national view of Romanticism are crossed, it usually remains a juxtaposition of different forms of Romanticism without it becoming clear what could hold the different Romanticisms in Europe together.

However, when looking for similarities between Romantic painters, one should not limit oneself to subjects and motifs or forms of representation and styles. What artists like Turner, Delacroix and Friedrich do share is the experience of the beginning of modernity, whose dark sides became increasingly clear after the dawn of the Enlightenment. Romanticism – not only in

painting, but also in literature and philosophy – can be understood as a particularly early and profound critical meditation on the beginning of modernity. Tis could also help locate an important similarity between different types of Romantic painting. Te violations of convention in the landscape paintings of Friedrich, Turner and Constable – despite all other differences – make it clear that man’s relationship to nature is being made an object of thought in a new way. Man is no longer just straightforwardly embedded in nature; but neither is he alone in facing it as a sovereign subject at a safe, reflective distance. Many Romantic painters – regardless of all their significant differences – seem to share the desire to question usual perspectives in order to use their pictures to raise questions and open up spaces for thought rather than clinging to old answers. It is striking, for example, how often Romantic paintings experiment with redefining the point of view and the role of the viewer or deliberately unsettling them.

In general, in Romantic painting, the image gains power over its viewers in a new way: its effect is no longer based primarily on the fact that it deceives and blurs the difference between image and reality. Rather, more and more images are now being created that are

Overleaf: The Large Enclosure, 1832

immediately recognizable in their manufactured and artificial nature and yet still have an effect that is difficult to explain. Te texts with which Clemens Brentano and Heinrich von Kleist responded to Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea exemplify this phenomenon. Brentano describes how he is unable to enter the landscape depicted and that he can only find what he was previously looking for in a picture in the space between himself and the painting. Kleist edited Brentano’s text and added a famous metaphor: the viewer of Friedrich’s painting would feel like someone whose eyelids have been cut away. In other words, although, as Brentano had noted, the image does not aim to create a deceptive illusion, it has acquired an uncanny power.

Te time spent looking at the picture is of increased importance. Romantic painters seem to have given particular thought to how viewers of their paintings could become involved in long, demanding processes of perception and reflection. Te idea of not aiming at the creation of a striking impression, but rather at stimulating a longer period of reflection, could be associated with political motivations, though this deviates from common forms of propagandistic use of images. With his painting Hutten’s Tomb, Friedrich seems to invite an open thought

Opposite: Hutten’s Tomb, 1823-24

process that does not convey a clear, catchy message, but rather has a political effect in that it counters the supposedly no-alternative politics of the post-Napoleonic era with an openness of reflection and contemplation. A comparable concern could be articulated in images that at first glance seem to have nothing to do with Friedrich’s painting. If the art critic Gustave Planche is right when he points out that Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People needs to be studied for a similar length of time as Mozart’s Don Giovanni or Rossini’s Semiramide, then this means the picture is not just a brief snapshot of the maelstrom of the revolutionary days, but about a longterm vision and thinking that frees itself from the time pressure of the revolutionary situation. Te same applies to the late paintings of Turner, which, when viewed for a longer period of time, increasingly push perception to its limits. Te fact that images give us time to think openly in this way could be characteristic of Romanticism. Perhaps Friedrich, Delacroix and Turner are closer than we are used to thinking. And perhaps Friedrich has more in common with other Romantic painters in Europe than his characterization as a German Romantic would lead us to believe.

Opposite: Easter Morning, c. 1828-35

Following pages: Mountain Peak with Drifting Clouds, c. 1835

Precisely because his art is now remarkably famous and popular, it is difficult for us to look at Friedrich’s pictures unbiasedly and with a fresh eye. Tis makes it all the more important to question traditional patterns of interpretation. In addition to his pictures, his letters and writings give us the opportunity to distance ourselves from the stereotypes and clichés that have developed over a long period and now seem self-evident. In Friedrich’s own texts, for example in the posthumously titled Commandments of Art, what emerges above all is his roots in his Christian, or more precisely Lutheran, faith, which, so to speak, formed the compass for the artist’s life and work. Friedrich’s basic Protestant beliefs were accompanied by a pronounced humility towards God and creation, but also a sceptical view of sensuality, the sense of sight and images. Some of Friedrich’s paintings and drawings seem to use genuinely pictorial means to address the criticism of a false trust in the visible and in our eyes. A second leitmotif that profoundly shapes Friedrich’s thinking and runs through his writings is aimed at the value of individuality, at the ‘temple of individuality’, as he himself formulated it in the Commandments of Art. Tis ‘individuality’ comes with freedom for individual decisions, but also a special responsibility. What constitutes good art or a meaningful way of life can no longer be decided solely on the

basis of traditional normative rules, but must be thought through by each individual and accountable to God.

In addition to Friedrich’s texts, early reactions to Friedrich’s art and contemporary descriptions of his personality merit attention. On the one hand, they show how differently Friedrich and his pictures could be perceived. On the other hand, some of these sources mark important starting points for an image of Friedrich that continues to have an impact today. Goethe’s statements can draw attention to the fact that today’s widespread opposition between classicism and romanticism is questionable and all too crude. When the classicist Goethe became acquainted with Friedrich’s elaborate sepia drawings in 1805, he was very appreciative and awarded the still unknown artist recognition that significantly boosted his reputation. And even later – even in the fundamental criticism of Romantic art that Goethe and Johann Heinrich Meyer published in 1817 under the title New German Religious-Patriotic Art – Goethe’s judgments about Friedrich remain characterized by respect.

Te characterizations of the painter written by Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert and Carl Gustav Carus are marked by the fact that both authors were his close friends for a long time. Teir descriptions are

Overleaf: Seashore in the Fog, c. 1807

correspondingly multifaceted. But these sources should also be read with caution and critical distance, as Schubert and Carus seem to have imaginatively supplemented and coloured established facts in some parts. It is for instance by no means certain that Johann Christoffer Friedrich, the painter’s brother actually died while skating on the ice, as Schubert and Carus report, since the parish registers for 1787 only report a death by drowning in the Greifswald moat and historical weather data cast doubt on the notion that the ditch was frozen at the time of death. Parts of the characterization that Carus gives of Friedrich raise further questions. Did the painter actually never learn a foreign language and have contact only with German-speaking circles during the four years in which he attended the academy in Copenhagen? And given the social networks in which Friedrich moved, which can still be reconstructed today, shouldn’t the claim that Friedrich was ‘almost never seen in company’ be put into perspective? After all, Schubert reports that the painter could be inclined to joke ‘when he was socially with others’. Last but not least, Carus’ comments on Friedrich’s psychological state should be read with caution. As a doctor who himself dealt intensively with questions of psychology, Carus was undoubtedly particularly attentive to pathological developments in mental states. However, it cannot be ruled out that he

is being disingenuous when he tries to explain the increasing estrangement between himself and Friedrich by attributing it to the painter’s state of mind.

What is, however, particularly valuable is the information that Carus gives about Friedrich’s working method, process and understanding of images. Friedrich’s keen awareness of the inherent logic of the image is reflected in Carus’ remarks on the difference between the usual view of the surroundings and the observation of the image when he describes the image as a ‘fixed gaze’.

Te surviving contemporary descriptions of Friedrich and his art offer valuable insights into the painter’s life and work and in this way enrich the view of his pictures. However, readers of these texts should keep in mind that Friedrich’s contemporaries were already faced with the same challenge that still concerns us today: they tried to understand an unusual artist without being able to know everything about him, his art and its background. After reading, we are all the more invited to immerse ourselves in his pictures with a keen, attentive eye.

An earlier, shorter French version of this introduction appeared in the journal Dossiers de l’art (no. 317: Caspar David Friedrich. Génie du romantisme, pp. 26–35).

Overleaf: Two Men Contemplating the Moon, c. 1819-20

paralysed by a stroke. He felt that he did not have long to live and wept like a child when he told me the following: ‘The Russian Tsar visited my studio when he was still a grand duke. He was unusually gracious to me and said to me: “Friedrich, if you are ever in need, let me know, I will help you.” Now I am in great need, I can no longer hold the brush; soon I will die and my family will remain in poverty.’ Friedrich died that same year! I recently received the letter from St. Petersburg that I enclose. It had been lying there for a whole year because it arrived during my absence. Therefore, I was unable to bring its contents to the attention of our Master and Tsar. I hasten to do so now, and given that Friedrich died in the hope that he could repose his trust in the Tsar, I told his family to turn to me so I might report their situation to His Majesty. I request that Your Imperial Highness present my letter and the enclosed letter to our Master and Tsar. If it please His Majesty to do something for the wife and children of Friedrich, then our envoy at the Saxon court will locate them in Dresden, if they are there, or find out where they are living. Of course, I could also take it upon myself to fufil the wishes of His Majesty in this matter.

CASPAR DAVID FRIEDRICH: ‘I had just stepped out...’ describes the small town of Elsterwerda in Brandenburg, which Friedrich probably passed through on a trip home to Greifswald in the summer of 1806. ‘Spring – Morning – Childhood’ relates to the first drawing in a cycle of the Seasons – Times of Day – Stages of Life; both text and drawing possibly date from 1803. The COMMANDMENTS OF ART were probably first conceived around 1809; the text here is taken from a fair copy in Friedrich’s hand of a revised version datable to about 1818, which belonged to the painter J. C. Dahl. For these and all of Friedrich’s other writings and his letters see Johannes Grave, Petra Kuhlmann-Hodick and Johannes Rößler (eds.), Caspar David Friedrich: Sämtliche Briefe und Schriften, Munich, 2024.

CARL GUSTAVUS CARUS (1789-1869), physiologist and artist, studied painting under Friedrich. A friend of Goethe, he is also credited with the development of the idea of the unconscious, and of the vertebrate archetype, a major concept for the theory of evolution. The first section given here is taken from Memories of my life and notable events, published in 1865-66. The second section was the preface to the memorial volume about Friedrich that Carus published in 1841.

JOHANN WOLFGANG VON GOETHE (1749-1832) poet, scientist, statesman and theorist of æsthetics, is the most significant figure in German cultural life of his period. His life-long friend and colleague, JOHANN HEINRICH MEYER (1760-1832), was a painter, teacher and art critic.

HEINRICH VON KLEIST (1771-1811), dramatist, novelist and patriot, was a friend of Friedrich and also wrote on æsthetics. ACHIM VON

ARNIM (1781-1831), poet and patriot, and CLEMENS VON BRENTANO (1778-1842), poet and novelist, together collected German folk songs

ON TEXTS AND

which they published as Des Knaben Wunderhorn. The first section was written by Kleist, reusing material supplied by Brentano and Arnim, (including the metaphor of the eyelids being cut away) and was published by Kleist in the newspaper Berlin Abendblätter which he was then editing. The dialogues are by Brentano and Arnim.

GOTTHILF HEINRICH VON SCHUBERT (1780-1860) was a doctor, botanist and psychologist. His religious understanding of the natural world was extremely influential in German romanticism, with his two most famous books being Symbolism of Dreams (1814) and History of the Soul (1830). He lived in Dresden between 1806 and 1809. His recollections of Friedrich were published in his Autobiography (1854-56).

VASILY ANDREYEVICH ZHUKOVSKY (1783-1852) was the leading figure of the Romantic movement in Russia, and translated many of the great works of his German contemporaries, as well as nurturing the careers of younger writers such as Pushkin and Gogol. He was tutor to the Grand Duchess Alexandra Feodorovna, later Tsarina, and her son, later Tsar Alexander II. His letters were variously published between 1885 and 1961 and are taken here from S. Hinz, Caspar David Friedrich in Briefen und Bekentnissen (1974).

List of illustrations

Unless otherwise indicated, all works are oil on canvas

p. 1 Detail of Georg Friedrich Kersting, Caspar David Friedrich on his journey through the Giant Mountains, 1810, watercolour over pencil on light grey paper, 310 x 242 mm, Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

p. 2 Chalk Cliffs on Rügen, c. 1818, 90 × 71 cm, Kunst Museum Winterthur

p. 4 Window with a View over a Park, c. 1810-11, sepia and pencil on paper, 398 x 305 mm, Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

p. 6 The Ruins of Oybin Abbey (The Dreamer), c. 1835, 27 x 21 cm, Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

p. 8 The Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, c. 1817-18, 95 x 75 cm, Kunsthalle, Hamburg

p. 11 Rocky ravine in the Elbe Sandstone Mountains, 1822-23, 94 x 74 cm, Belvedere Museum, Vienna

p. 12 The Chasseur in the Forest, 1814, 66 x 47 cm, Private collection

pp. 16-17 The Ruins of Eldena in the Giant Mountains, 1830-34, 72 x 101 cm, Pommersches Landesmuseum, Greifswald

p. 19 The Ruins of Eldena Abbey, 1814, grey ink and watercolour, 159 x 165 mm, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

p. 22-23 The Large Enclosure, 1832, 73 x 102 cm, Galerie Neue Meister, Dresden

p. 25 Hutten’s Tomb, 1823-24, 73 x 93 cm, Klassik Stiftung Weimar, Weimar

p. 26 Easter Morning, c. 1828-35, 44 x 34 cm, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

pp. 28-29 Mountain Peak with Drifting Clouds, c. 1835, 25 x 31 cm, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth

p. 32-33 Seashore in the Fog, c. 1807, 34 x 50 cm, Belvedere Museum, Vienna

pp. 36-37 Two Men Contemplating the Moon, c. 1819-20, 34 x 44 cm, Galerie Neue Meister, Dresden

p. 40 Newbrandenburg in the Morning Mist, 1816, 71 x 92 cm, Pommersches Landesmuseum, Greifswald

pp. 42-43 Spring –Morning – Childhood from the cycle Seasons – Times of Day –Stages of Life, c. 1803, sepia ink over pencil on paper, 192 x 275 mm, Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin

p. 46 The Cross in the Mountains, c. 1812, 45 x 38 cm, Kunstpalast Museum, Düsseldorf

pp. 48-49 Mountain Landscape with Rainbow, 1809-10, 70 x 102 cm, Museum Folkwang, Essen

p. 51 The Rock Gate at Neurathen, c. 1826-28, 279 x 245 cm, Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

p. 54 Self-portrait, c. 1810, grey chalk on paper, 229 x 182 mm, Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin

p. 56 Boy sleeping on a tree stump, watched by a raven, an axe below (sketch for a woodcut), c. 1800-2, pencil, brush in brown ink, pen in black and brown ink on paper, 181 x 116 mm, Kunsthalle, Bremen

pp. 58-59 Dawn in the Giant Mountains, c. 1830-35, 72 x 102 cm, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin

p. 61 A Wood in Moonlight, c. 1823-30, 70 x 49 cm, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin

pp. 64-65 Moonlit Landscape, before 1808, watercolour on paper; moon cut out and inserted on a separate piece of paper; laid down on cardboard, 232 x 365 mm, Morgan Library, New York

p. 67 The Port of Greifswald, c. 1818-20, 90 x 70 cm, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin

p. 68 Woman at a Window (Caroline, wife of the artist), 1822, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin

pp. 70-71 The Northern Sea in Moonlight, 1823-24, 22 x 30 cm, Národní galerie Praha, Prague

pp. 76-77 Abbey among Oak Trees, c. 1809-10, 171 x 110 cm, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin

p. 80 Rock Arch in the Uttewalder Grund, c. 1801, sepia ink and wash over pencil on paper, 706 x 500 mm, Museum Folkwang, Essen

pp. 82-83 Eastern Coast of Rügen Island with Shepherd, c. 1805-6, sepia ink and wash, white gouache and pencil on paper, 616 x 990 mm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

pp. 86-87, 88 & 96 The Monk by the Sea, c. 1800-2, 110 x 171 mm, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin

p. 100 Georg Friedrich Kersting Caspar David Friedrich in his studio, c. 1812, 51 x 40 cm, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin

pp. 102-103 Hill and Ploughed Field near Dresden, c. 1824, 22 x 30 cm, Kunsthalle, Hamburg

pp. 106-107 After the Storm, 1817, 22 x 30 cm, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

p. 108 Oak Tree in the Snow, 1829, 71 x 48 cm, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin

pp. 110-111 Morning Mist in the Mountains, 1808, 71 x 104 cm, Thüringer Landesmuseum Schloss Heidecksburg, Rudolstadt

pp. 116-117 Woman in front of Setting [or Rising?] Sun, c. 1818, 22 x 30 cm, Museum Folkwang, Essen

pp. 120-121 The Stages of Life, 1835, 72 x 94 cm, Museum der bildenden Künste, Leipzig

p. 123 The Cross beside the Baltic, c. 1815, 45 x 33 cm, Schloss Charlottenburg, Berlin

p. 126 On the Sailing Boat, c. 1819, 71 x 56 cm, Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

p. 130-31 Moonrise over the Sea, c. 1821, 135 x 170 cm, Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

p. 133 Early Snow, 1827, 44 x 34 cm, Kunsthalle, Hamburg

p. 134 The Cemetery, c. 1825, 143 x 110 cm, Galerie Neue Meister, Dresden

Images courtesy holding institutions, and/or Wikimedia

First published 2025 by Pallas Athene (Publishers) Limited

2 Birch Close, London N19 5XD www.pallasathene.co.uk

© Pallas Athene 2025

ISBN 978 1 84368 254 7

Printed in England

Series editor: Alexander Fyjis-Walker

With many thanks to Susie Lendrum for extensive assistance with translations, and to Johannes Grave for allowing us to consult his co-edition of Friedrich’s writings.

With thanks also to those museums that have made their images freely available

Cover:

Detail of Self-portrait, 1800, black chalk on paper, 420 x 276 mm, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen