First published on the occasion of the exhibition

‘Michael Craig-Martin’

Royal Academy of Arts, London 21 September – 10 December 2024

Lead supporter

Generously supported by

First published on the occasion of the exhibition

‘Michael Craig-Martin’

Royal Academy of Arts, London 21 September – 10 December 2024

Lead supporter

Generously supported by

Batia and Idan Ofer

The Michael Craig-Martin Supporters Circle:

Lord and Lady Davies of Abersoch

J P Marland Charitable Trust

Valerie and Philip Marsden MBE

Bianca and Stuart Roden

Dasha Shenkman OBE and those who wish to remain anonymous

With additional support from

Catalogue supported by

Joe and Marie Donnelly

This exhibition has been made possible as a result of the Government Indemnity Scheme. The RA would like to thank HM Government for providing Government Indemnity and the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and Arts Council England for arranging the indemnity.

DIRECTOR OF EXHIBITIONS

Andrea Tarsia

EXHIBITION CURATORS

Axel Rüger

Sylvie Broussine

Colm Guo-Lin Peare

EXHIBITION ORGANISATION

Joanna Weston

Guy Carr

PHOTOGRAPHIC AND COPYRIGHT CO-ORDINATION

Caroline Arno

EXHIBITION CATALOGUE

Royal Academy Publications

Florence Dassonville, Production and Distribution

Co-ordinator

Carola Krueger, Production and Distribution Manager

Peter Sawbridge, Head of Publishing and Editorial Director

Copy-editing and proofreading: Alison Hissey

Design: Lizzie Ballantyne

Colour origination: DawkinsColour

Printed in Wales by Gomer Press

Copyright © 2024 Royal Academy of Arts, London

Any copy of this book issued by the publisher is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including these words being imposed on a subsequent purchaser.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-915815-09-5

Distributed outside the United States and Canada by ACC Art Books Ltd, Riverside House, Dock Lane, Melton, Woodbridge, IP12 1PE

Distributed in the United States and Canada by ARTBOOK | D.A.P., 75 Broad Street, Suite 630, New York, NY 10004

EDITORIAL NOTE

All works illustrated are by Michael Craig-Martin unless otherwise stated. Capitalisation policies for titles of works of art throughout this book are those of the artist.

Dimensions of all works of art are given in centimetres, height before width before depth.

Page 2: detail of cat. 56; page 7: detail of cat. 126; page 9: detail of cat. 60; page 10: detail of cat. 121

MICHAEL BRACEWELL

‘Ever since I was a child I have been entranced by the visual world. One might say that I am more interested in appearance than meaning. In my work I have always sought to find a balance between ideas and aesthetics.’

Michael Craig-Martin1

‘The simple things you see are all complicated.’

The Who, ‘Substitute’, 1966

Immediate, inscrutable, vivid, cool, neutral, complex, concise, confrontational, simple, joyous, modern, epic, compelling. All these adjectives – including those that contradict one another – apply to the art of Michael Craig-Martin. His art speaks with eloquence and verve about the modern world – our tech-based, mass-media, mass-production, consumerist, culturally aware global society. An urban society of quotidian products, information, services, sign systems, design, tools. A world in a constant state of acceleration. ‘How could I not draw a mobile phone?’ Craig-Martin has said, ‘The world is now filled with things that are transitory – I have found myself to have become a chronicler of our ever-changing times.’2

Since his student days in the early 1960s CraigMartin has explored and questioned the existential basis of artistic process – of what art can be and might be. In his own words: ‘What is art’s most essential element? Talent, craftsmanship, transformation, meaning, emotional power, originality, nomination, the artist’s hand, materiality, personal expression, imagination, belief? What can art be, what can be art?’3

As represented within his art, Craig-Martin’s subjects – most of which are ordinary, domestic and ubiquitous – have the air of items or entries in a visual directory (see for example figs 1–3). They are at once hyper-distinctive and curiously emptied of any meaning save that contained in their function and identity. As Richard Shone has observed: ‘From the very start, no social critique lurked behind his choice of modest objects: they happened to be his own and available.’4

Likewise, no irony, be it romantic, political, camp or post-modern, is in play. Rather, each work comprises a near-diagrammatic representation of its subject, graphically or sculpturally, that exists solely as itself, cleared of connotation.

So, within the dizzying range of visual culture and the history of art, to which movement, school or affiliation might the art of Michael Craig-Martin be assigned with any confidence? This is not an easy question to answer. His work – a continually developing process, finding a position, testing the ground – evades neat categorisation. Even at the viewer’s first arresting impressions, one could

argue for the influence of pop art, minimalism, conceptualism, post-modernism and indeed any mix, remix or hybrid of these designations. But CraigMartin’s art doesn’t correspond directly to any of them.

Rather, in his painstaking refinement of a pictorial style that is also a method (or better still, a principle), Craig-Martin’s art unpacks the inner workings of these concepts: their formalism (or their rejection of this), their semiotic code or meaning (or their denial of this), their aesthetic agenda (or their rearrangement of this), their ambition, sociology, artistic intent. Indeed, the exploration of artistic intent – the questioning of image and representation, of artmaking itself and how we look at art – is the central and primary motivation of Michael Craig-Martin’s work and thinking.

So what do you get?

Craig-Martin has written: ‘My work is my response to the world around me. I do not think of myself as having something to “say” or express or to teach.’5

Whether sculptural, two-dimensional, painting, drawing, mixed media, digital or in the form of studies, the visual presence (you might say ‘resonance’) of Craig-Martin’s art is at once familiar (filing cabinet, fan, ladder, torch, umbrella) and strangely, icily distanced. Graphic, domestic or epic; quotidian subjects as neat and sharp as any technical drawing – yet an art whose intentions and motivations seem immediately to lie elsewhere. There is a tension in these depictions; a rearrangement of the relation between subject, form, colour, aura and meaning that renders them also alien, remote – results from an orbiting database, maybe. Too strange to be solely decorative. They make no effort to please; their apparent simplicity is compelling, aloof and emphatic. But there is also comfort in the familiarity they depict or represent.

The precision, design, spectacle, the vivid contrasts of colour and bold outline, the sculptural riddle or pictorial itemising of the modern world, this ‘chronicling’ – it’s almost forensic – become an invitation to participate in a deeper enquiry. Put another way, the formalist and aesthetic aspects of Craig-Martin’s art comprise an alibi for their primary artistic activity, which, beyond expressing nothing but themselves (the artist’s ‘response to the world’), is interrogative.

The nature of this enquiry is both artistic and philosophical. It concerns the nature of representation and the processes of perception at their most fundamental. It questions the artist and the artwork

as much as the viewer. But this is not to say that the art of Michael Craig-Martin cannot be enjoyed for the sheer visual pleasure of its formalist values and chromatic exuberance. The thinking behind those qualities, however, is derived from this deeper speculation and is apparent in their heightened relation to representation. His works investigate the ‘essence’ of art, as Craig-Martin has put it. Its mystery and workings, at their most fundamental level.

Such an endeavour, attended and assisted in CraigMartin’s art by a clear allegiance to enlightenment, aesthetic awareness, self-knowledge, intelligence and open-handed generosity, continues a liberal humanist tradition of art and visual culture that goes back through generations of artists (and viewers) to the Renaissance and quite possibly further.

As an analytical-artistic project it is perhaps more instinctive than intellectual, prompted at root by the artist’s formative experience of the boom in technology, consumerism and automobile society that America experienced in the 1950s. A world in which product design and advertorial culture proposed a brilliance and glamour to ‘newness’ as the agent of a consumer utopia. And with it, a new wave in sociology and media studies.

This absorption of amplified and glamourised modernity (an industrially researched, designed, constructed and marketed glamour, above all) was deepened and extended through Craig-Martin’s exposure as a student at Yale University in the early 1960s to proto-pop and pop art in New York, accompanied by his contact with radical developments in literature, music and dance.

All these new lines of enquiry, interconnected by their analysis of modern experience, and the vantage point they opened to consider the artistic iconoclasms of modernism, from Duchamp to Warhol, informed and encouraged Craig-Martin’s early work. ‘The late 1950s and 1960s were a period of exceptional innovation in art and I was fortunate to be a student at the time… It was also a period of radical thinking in many fields: John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Gertrude Stein, Sam Beckett, Buckminster Fuller, Marshall McLuhan, Ludwig Wittgenstein.’6 Works in media studies such as Marshall McLuhan’s The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man (the original essays published as early as 1951 in America) kept in perfect step with the protopop and pop art deliberations about art’s dialogue with the new mass-cultural world.

Craig-Martin’s art and thinking complement those of Richard Hamilton in their specific exploration of

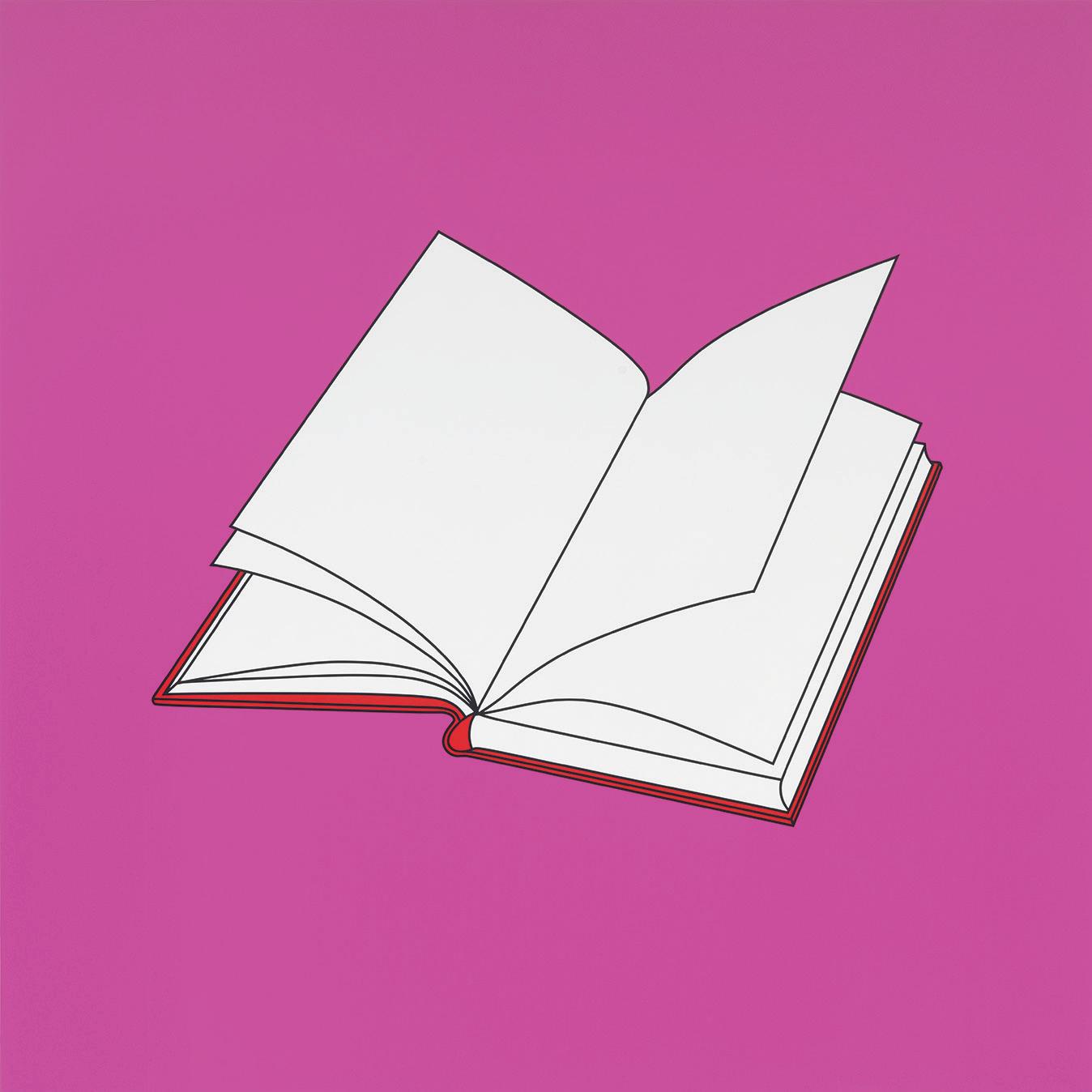

Fig. 2 Untitled (with coffee cup), 2020. Acrylic on aluminium, 120 x 120 cm

Fig. 3 Untitled (book), 2014. Acrylic on aluminium, 200 x 200 cm

Although Michael Craig-Martin is probably best known for his vibrantly coloured images of everyday objects, he focused after his graduation from art school at Yale University in the 1960s on conceptual sculptural works devoid of colouring because, in line with the spirit of the time, he felt colour represented ‘empty formalism, banal self-expression, the decorative, arbitrary and indulgent’.1

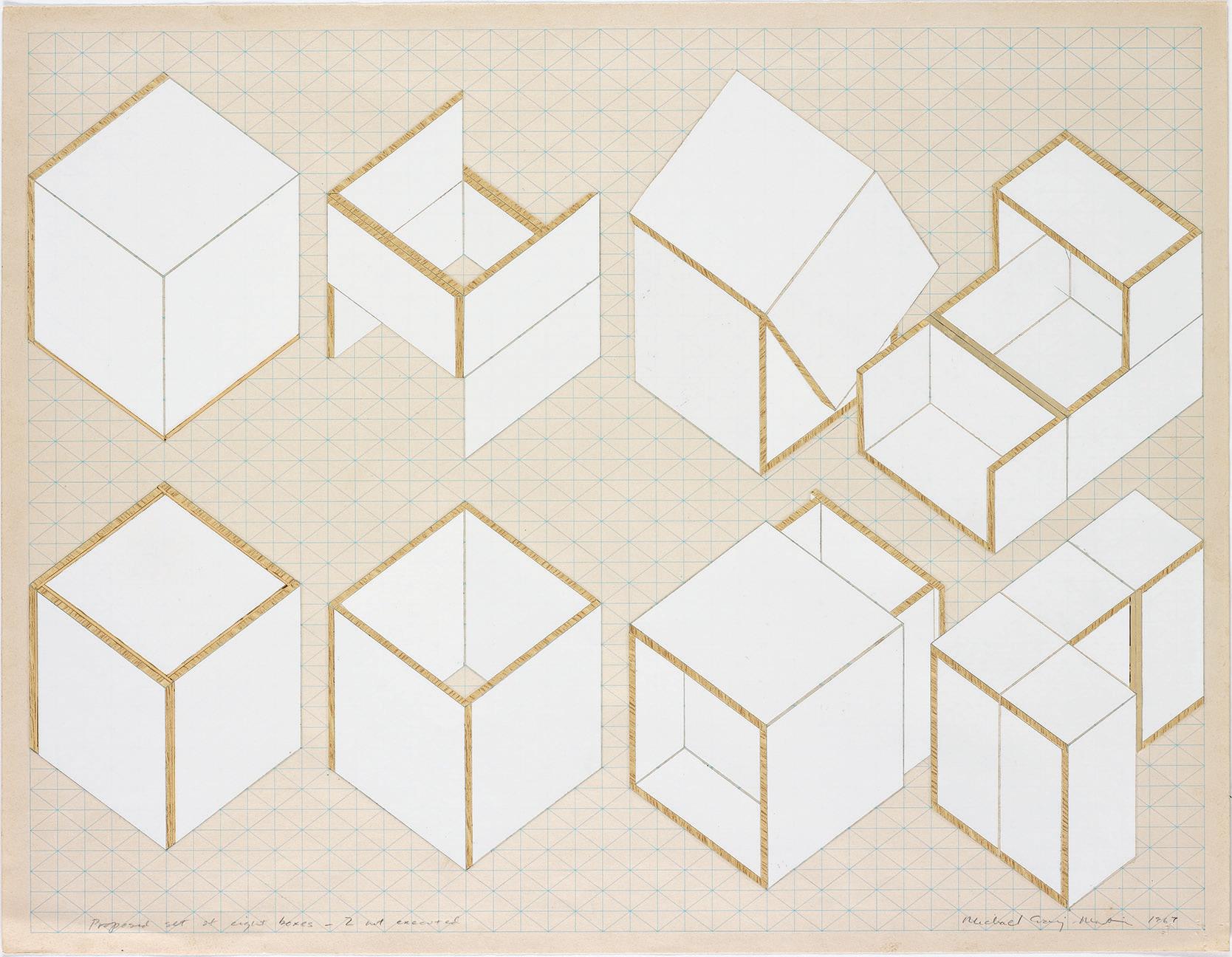

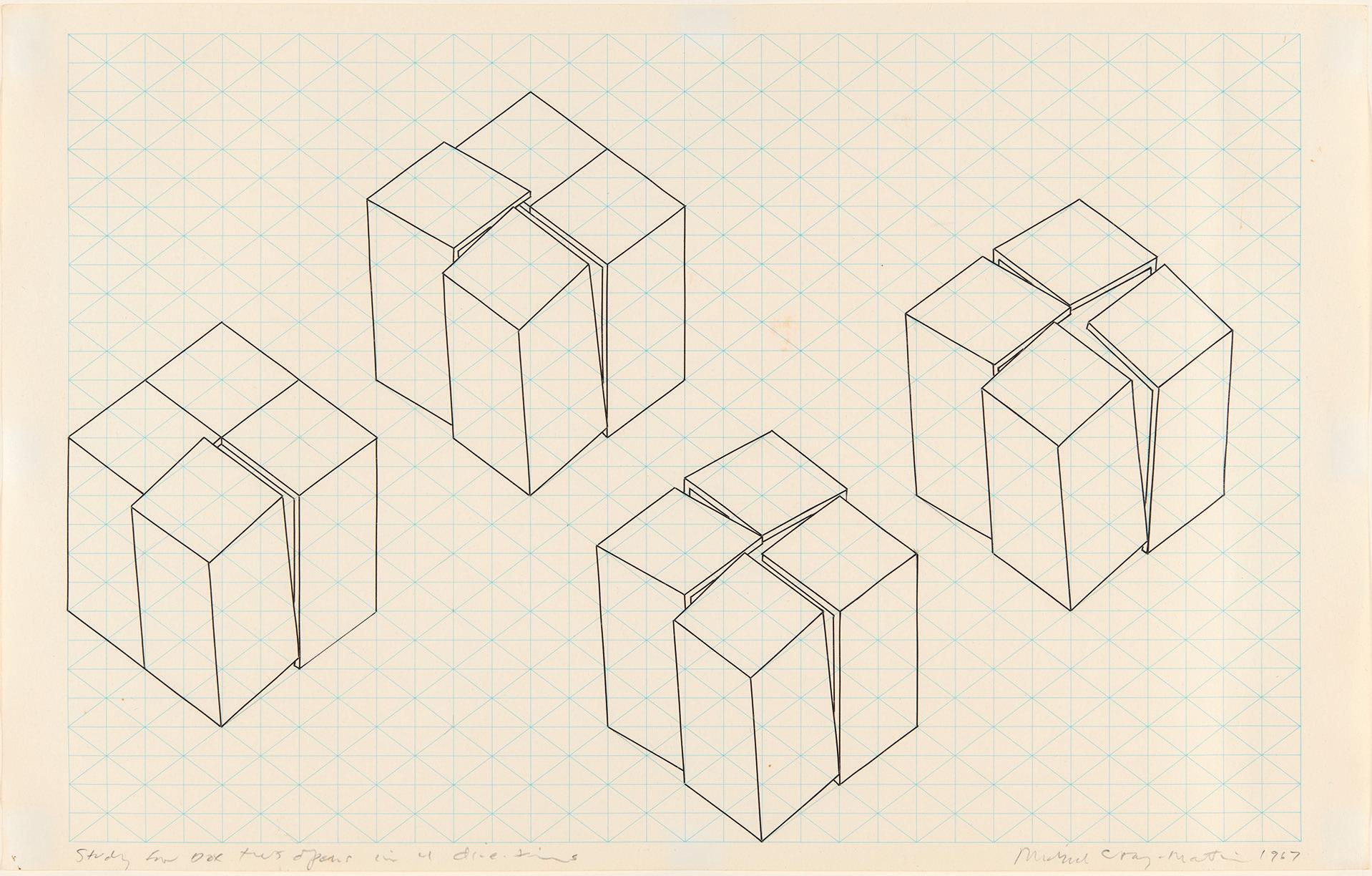

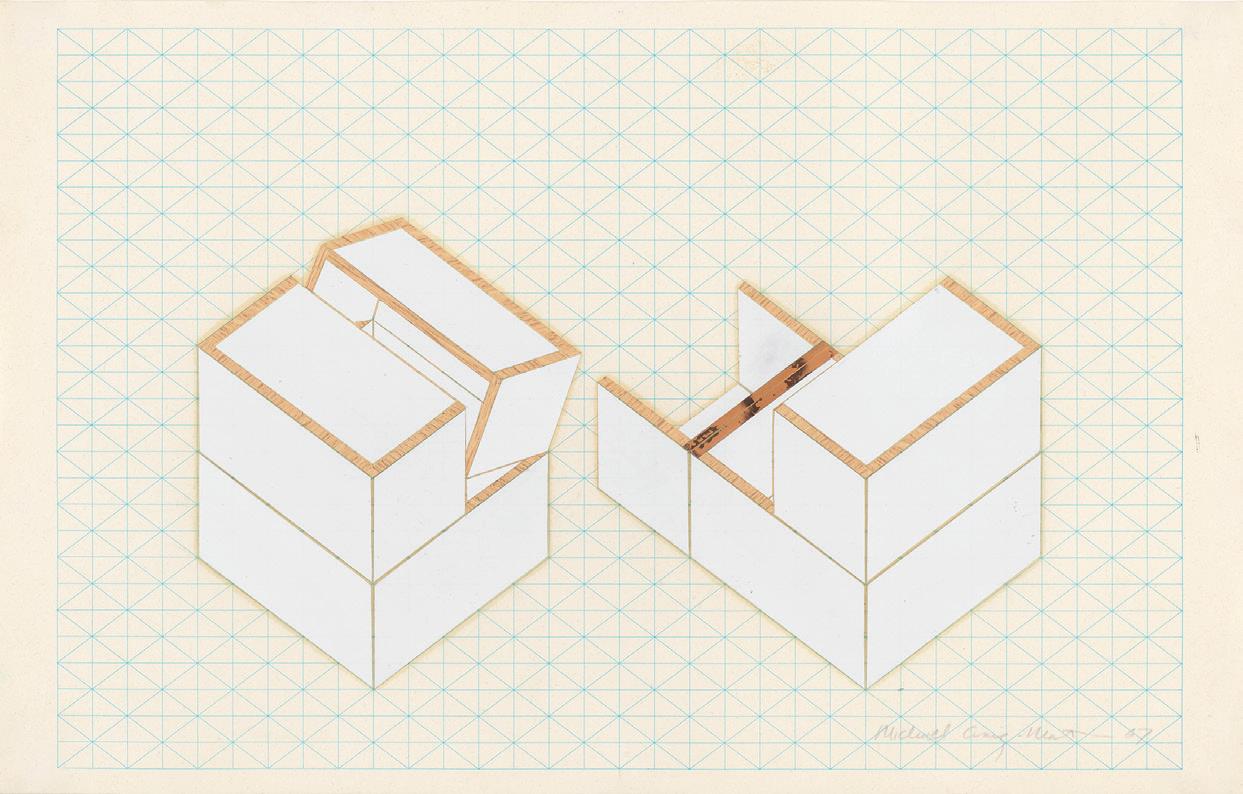

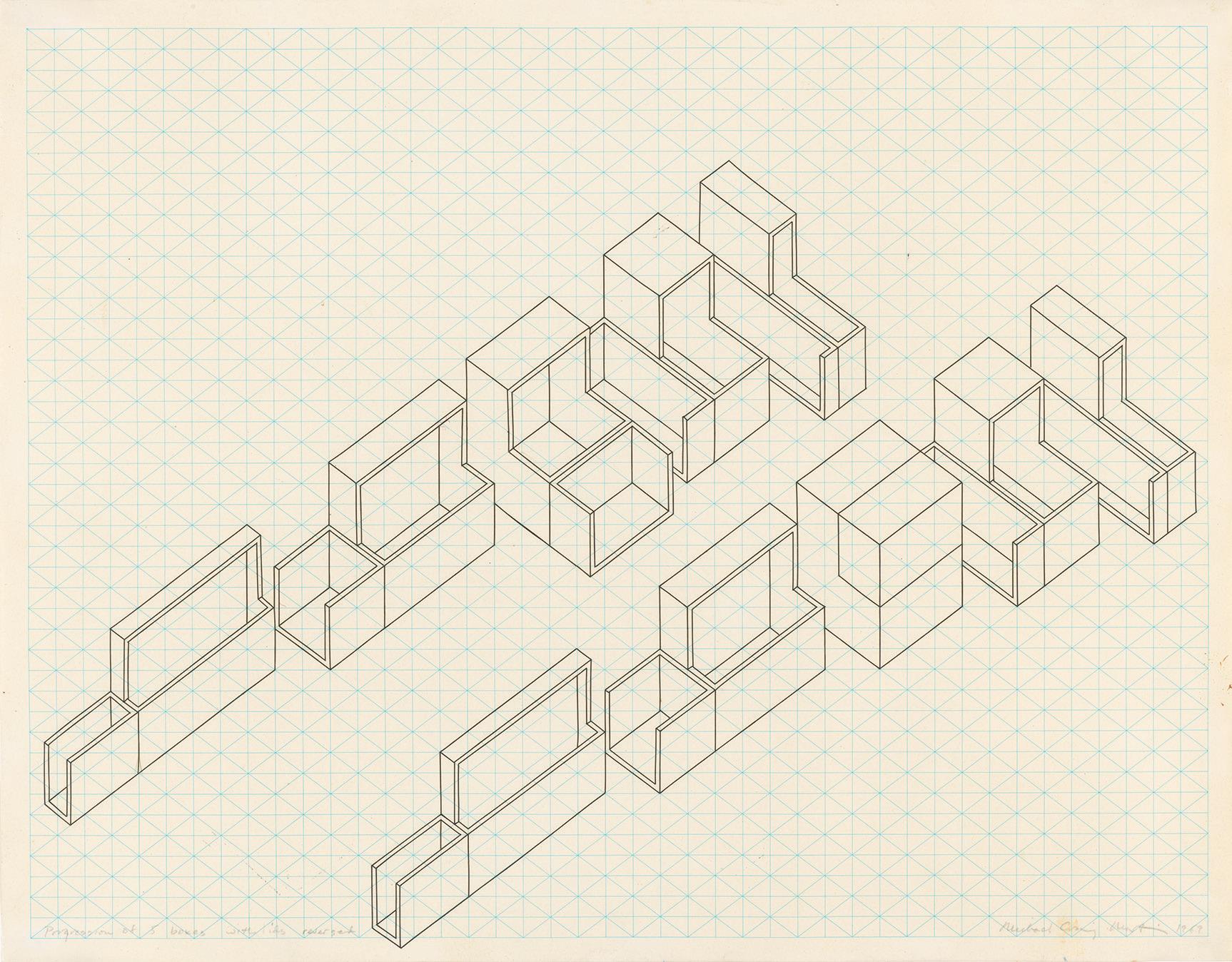

His earliest work here is the modestly sized Black Book (1967; cat. 1), which takes a familiar object, a book, and transforms it into a sculpture that is a hybrid between a book and a box. CraigMartin was greatly inspired by the minimal geometric forms and slick surfaces of Donald Judd’s boxes. But while his box sculptures – developed first in meticulous drawings on graph paper (cats 2–6) –were as minimalist as Judd’s, they also suggested utilitarian qualities in that their hinges and handles invited viewers to interact with them, to open and close them. In Box that Never Closes (1967; cat. 7), the artist plays with the viewer’s expectations and frustrations: the box looks like it ought to close, but it doesn’t. Formica Box (1968; cat. 8) turns out not to be a box at all when it is opened up. The idea here is that it is a sculpture that, as the artist says, ‘you could close and “put away”’.2 These boxes were to be CraigMartin’s last free-standing sculptures until his recent sculptures of drawn objects.

His next sculptures were largely wall-based and take further his interest in simple, mass-produced, readymade objects, among them buckets, milk bottles, pencils, clipboards. Four Complete Clipboard Sets… (1971; cat. 14) and Four Complete Shelf Sets… (1971; cat. 15) invite the viewer to detect the differences between the elements within each set, as the artist adds and subtracts details between them. In a sense, they prefigure Craig-Martin’s much later digital

reworkings of famous paintings, in which the colouring of the digital image constantly changes, with details of the composition fading in and out.3 On the Shelf (1970; cat. 13) and On the Table (1970; cat. 12) play with the viewer’s perception in a different way, suggesting simultaneously both equilibrium and precariousness. In the former, the milk bottles are tilted at an alarming angle, whereas the horizon line formed by the water inside them suggests a safe balance. In the latter, almost as a visual joke, a carefully calibrated balance exists between the weight of the four water-filled buckets and the legless tabletop suspended from the ceiling. In a sense the buckets are supporting the table rather than the other way around. In the mirrors in the ironically entitled Conviction (1973; cat. 16) viewers are invited to reflect on their own perceptions of themselves, prompted by phrases such as ‘I recognise myself’ and ‘I know who I am’ interspersed with question marks. One glances into the mirrors in the vain hope of confirmation.

The most radical and most celebrated work of Craig-Martin’s early career is undoubtedly An Oak Tree (1973; cat. 17), which he presented to consternation from the public and critics at the Rowan Gallery in London in 1974.4 A simple glass of water sits on a wall-mounted glass shelf accompanied by a text in which the artist declares that he has transformed the glass of water into an oak tree. In the artist’s words, the work cuts to the essence of art, revealing ‘its single basic and essential element: belief – that is, the confident faith of the artist in his capacity to speak and the willing faith of the viewer in accepting what he has to say’.5 With this uncompromising work, Craig-Martin had reached a ‘full stop’, as he has described it himself, after which he felt he needed to challenge himself to find a new direction away from conceptual art.

2 Proposal for a group of eight box sculptures, 1967

Pencil and Fablon on isometric graph paper, 43.5 x 56 cm

The Trustees of the British Museum, 2011,7063.1. Purchased with funds bequeathed by Mrs V J Playfair

3 Study for box that opens in four directions, 1967

Hand-applied black crepe tape on isometric graph paper, 28.5 x 45 cm

Collection Irish Museum of Modern Art, Purchase, 2011

4 Box that doesn’t close, 1967

Pencil and Fablon on isometric graph paper, 40.5 x 27 cm

Courtesy of the British Council Collection

5 Progression of five boxes with lids reversed, 1969

Ink on isometric graph paper, 42 x 54 cm

Courtesy of the British Council Collection

Craig-Martin’s radical approach in both the form and content of An Oak Tree presented him with a challenge to find a way forward in his practice. This he found in pictorial representation and imagemaking. For him, the primary forms of the world, as seen in the earliest art forms, were those of objects in daily use rather than pure circles, squares or triangles. He takes inspiration from objects around him, objects that he uses. This practice echoes that of Vincent van Gogh, who explained in a letter to his brother Theo in 1889, that he insisted on working from the visible world rather than purely from imagination.6

Craig-Martin’s neon works were his first attempts at drawing objects instead of using them. In Pacing (1975; cat. 20), as different segments of the outline light up and go off again, the viewer gets the impression of walking past an open door and seeing, through its frame, parts of another door beyond. In Reading Light (1975; cat. 19), the lamp is always lit up and ‘present’ and becomes ‘more visible’ when the bulb goes on. For a while Craig-Martin was interested in the constantly changing nature of these images, but he ultimately felt his neon works had no future because they were too complicated and expensive to make. This idea of the image that is continuously adjusting, albeit in a very different format, was to return in his digital portraits (cats 134–37), in which the constituent colours go through seemingly unlimited variations.

Craig-Martin’s interest in working with found objects is expressed in his Untitled Painting No. 1 and No. 4 (cats 21, 23) and in Painting and Picturing (1978; cat. 24). He found small paintings in traditional styles by anonymous amateur artists in small London shops and inserted them into sections cut out of the upperleft corners of larger blank canvases. Interestingly, the amateur work in Untitled Painting No. 4 is a copy of one of Monet’s depictions of the Gare Saint-Lazare in Paris of 1877. Here Craig-Martin has appropriated a work by someone who themself appropriated a work by the great nineteenth-century French master. In Painting and Picturing the more complex composition of the inserted still-life prompted CraigMartin to retrace purely the outlines of its objects onto the surrounding blank canvas. Rather than in pen or pencil, he did this in black tape, which was to become his medium of choice for large-scale wall drawings. The work’s title echoes the thoughts of the American philosopher Robert Sokolowski, who coined the term ‘picturing’ for our, as Craig-Martin put it, ‘extraordinary ability to see certain forms as pictures and interpret them as such; without that capacity we would only see coloured shapes… it meant that the viewer of a representational image was not a passive receiver… but was actively implicated in the making of the representation… it allows us to experience the presence of a thing without the thing being present itself.’7 This is perhaps the best summary of CraigMartin’s underlying thinking about his work.

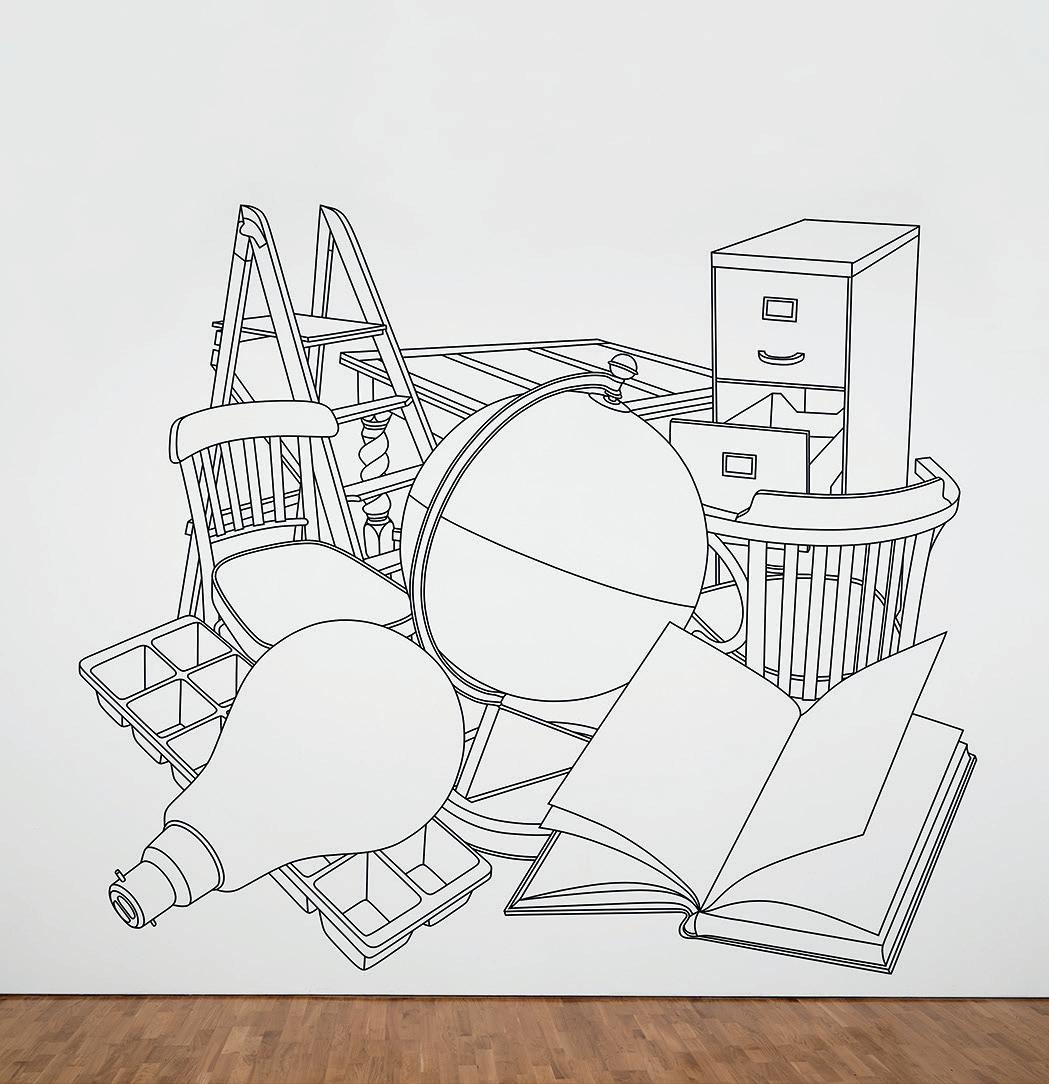

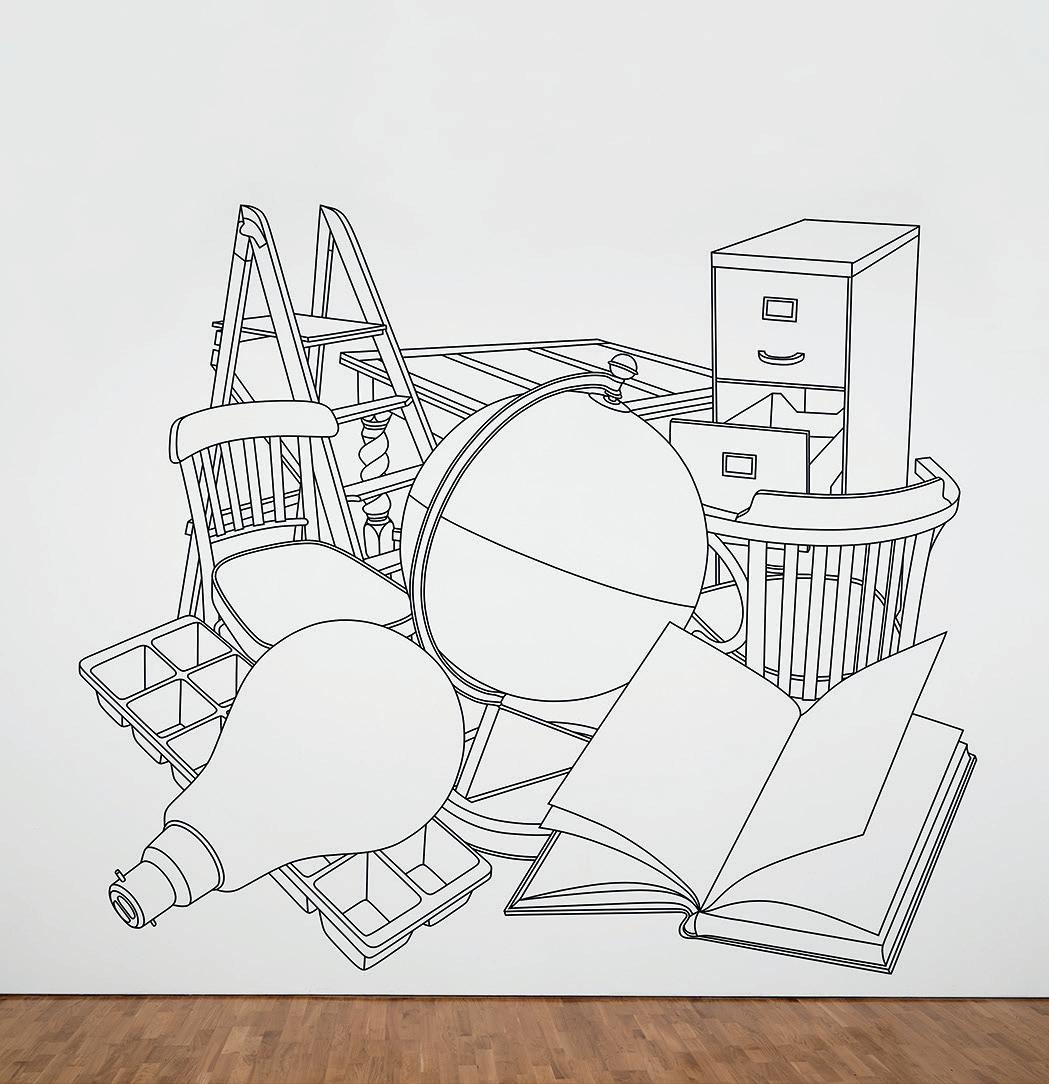

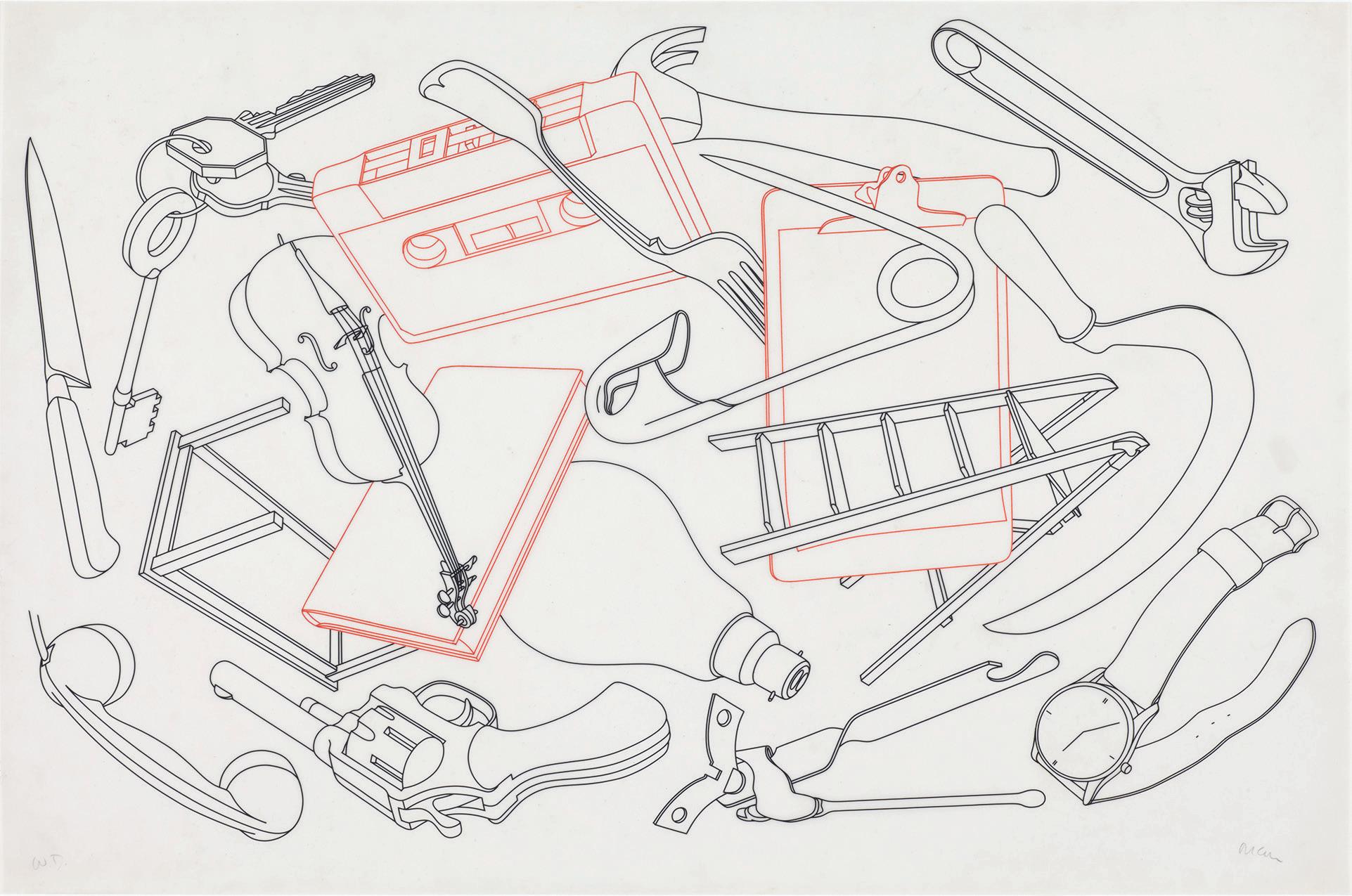

Craig-Martin presented his large-scale wall drawings in a landmark exhibition at the Rowan Gallery in London in 1978. At that time, he was greatly influenced by Duchamp and his readymades, as well as pop art and Warhol. But whereas Warhol concentrated on celebrity, readily identifiable consumer brands and iconic news imagery, CraigMartin continued with his interest in simple, easily recognisable, everyday manufactured objects. To him these were ‘more famous than famous. So famous that you don’t even notice them.’8 He has often commented on the challenge of finding objects that are so generic that they are instantly recognisable without any decorative detail or logos, so that they can be understood as universal representations. He searched for simple outline drawings of them, or ‘pictorial readymades’ as he called them, but to his surprise he could find none. So he started to produce his own drawings of these single quotidian objects. He chose a three-quarter view and showed them slightly from above in order both to indicate their three-dimensionality and to include as many aspects of the object as possible. Rather than using traditional drawing media, Craig-Martin used a crepe tape that had been invented in the 1960s to make drawings of electronic circuitry. He executed the drawings first on transparent acetate and then on translucent drafting film (see cat. 32) with the idea that each drawing could act as a template and be used repeatedly. His technique allowed him to achieve his ideal of making the drawings ‘styleless’, i.e. removing all trace of the artist’s individuality and ‘handwriting’. Craig-Martin wants the viewer to see the image, not the artist, and the linear simplicity of these drawings became his hallmark and the foundation of his work to this day. The transparency of the

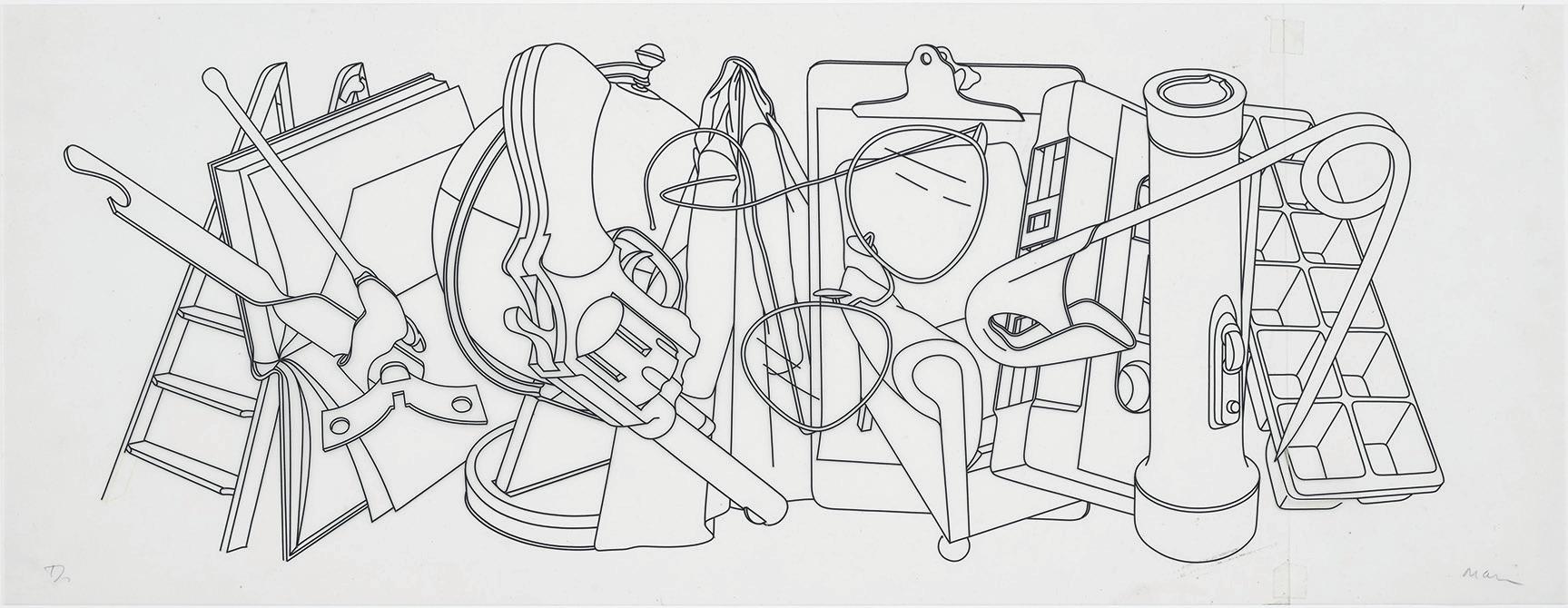

acetate allowed him to overlay several drawings to create different compositions to be projected onto the wall, which led to complex, even claustrophobic compositions (cats 25, 28, 33). In Reading with Globe (1980; cat. 25) he arranged the images like the figures in a family or group portrait, while in Modern Dance (1981; cat. 28) he placed four objects drawn in red tape in the foreground as if ‘dancing’ in front of a curtain of images. The same compositional principle the artist also applied in some of his prints, as in the Order of Appearance series (cats 46–49). In most of his works, the objects he depicts, while often densely clustered, retain their individual integrity, but in some of his drawings objects do invade each other’s space and become intertwined in improbably Escheresque compositions (cat. 33).9

After a sabbatical in New York in 1981–82, and inspired by the artist Julian Opie, who was then working as his studio assistant, Craig-Martin started to turn his drawings into wall-mounted sculptures, executed in thin, square-section metal rods (cats 35, 36), usually supported by coloured canvas or metal panels. Only in Globe (1986; cat. 34) does the coloured cube shape completely encase the globe, as if the world had been trapped inside an impenetrable box.

Towards the end of the 1980s Craig-Martin broke away from his dependence on representational drawn images. True to form, he made these new compositions of readymade objects – in this case Venetian blinds (1988–89; cats 43–45) – and mounted them on the wall. He saw them as references to painting, with their rectilinear shapes and solid colour fields suggesting a proximity to American Abstract Expressionist colour-field painting, while the closed blinds – by definition – negate the traditional view of painting as a window onto the world.

26 Tropical Waters, 1981

Hand-applied black and red crepe tape on drafting film, 60 x 91 cm

The Trustees of the British Museum, 2011,7063.2.

Purchased with funds bequeathed by Mrs V J Playfair

27 Study for Modern Dance, 1980

Hand-applied black crepe tape on drafting film, applied to both sides of the film, 61 x 91.5 cm

Jonathan & Natasha Bowers

Ms Isabella Lauder-Frost

Jessica Lavooy

Ms Patricia Lawrie

Mr Thierry Le Palud

Lady Lever of Manchester

Eykyn Maclean

Olivier and Priscilla Malingue

Mr Richard Mansell-Jones

Mr Alexis Martinez

Philip and Val Marsden CBE

Mrs Janet Martin

Mr Alexis Martinez

Dame Carolyn McCall DBE

Gillian McIntosh

Itxaso Mediavilla-Murray

Victoria Miro

Mr Alan Morton

Mrs Maggie Murray-Smith

Ms Minka Nyberg

Emma O’Donoghue

Neil Osborn and Holly Smith

Sir Michael Palin

Mr and Mrs D J Peacock

Cynthia Philips

Mr Adam and Mrs Michelle Plainer

Mary Pollock

Lady Purves

Ms Mouna Rebeiz

Peter Rice Esq

Erica Roberts

Miss Elaine Rowley

Mrs Janice Sacher

Mr Adrian Sassoon

Christina, Countess of Shaftesbury

David and Heather Shaw

Ms Elena Shchukina

Dr Shirley Sherwood OBE

Mrs Marianna E Simpson

Mrs Jane Smith

Lady Henrietta St George

Marc and Julie St John

Miss Sarah Straight

Mrs Ziona Strelitz

Mr Robert Suss

Ms Catherine Sutton

Anne Elizabeth Tasca

Ms Sally Tennant OBE

Mr Anthony J Todd

Mrs Kirsten Tofte Jensen

Ms Roxane Vacca

Marek and Penny Wojciechowski

John and Carol Wates

The Duke and Duchess of Wellington

Ms Christine Westwood-Davis

Mr and Mrs Anthony Williams

Mrs Adriana Winters

Yang Xu

David Zwirner and those who wish to remain anonymous

YOUNG PATRONS

Kalita al Swaidi

Dr Ghadah W. Alharthi

Miss Aishwarya Anam

Yevheniya Bazhenova

Mr Nicholas Bonsall

Mr Matthew Charlton

Miss XiaoMeng Cheng

Ms Caroline Cole

Thomas de Noronha e Silva Tomei

Rebecca Dolan

Sophie Dickson

Dr Brian Fu

Rebecca Glenapp

Dr Irem Gunay

Miss Amelia Hunton

Mr Phoebus Istavrioglu

Miss Minnie Kemp

Mr Callum Kempe

Ms Victoria Kleiner

Alinda Kring

Miss Matilda Liu

Mrs Louisa Macmillan

Anna Maj Madsen

Mr Jean-David Malat

Patrick McCrae

Mrs Aytan Mehdiyeva

Jessie Merwood

Miss Yekaterina Munk

Ms Madeleine Murphy

Mr Thomas Mustier

Miss Mimi Nguyen

Mr Garth Oates

Miss Lucinda Bellm, LAMB Gallery

Danielle Petitti

Ms Julie Scotto

Fazilet Seçgin

Irene Sieberger

James Simpson

Lindsay Smith

Gigi Surel

Ryan Sebastian Taylor

Maria Toxavidi

Mr Mattias Vendelmans

Ariana von der Heyde

Miss Lucy von Goetz

Mr and Mrs Harry Walker

Dimitrios Weedon-Topalopoulos

Celia You

Sofiya Zhevago

and those who wish to remain anonymous

PATRON DONORS

The de Laszlo Foundation

Kate de Rothschild Agius and Marcus Agius CBE

The William Brake Foundation

Mr D H Killick

The Michael and Nicola Sacher

Charitable Trust

Ms Cynthia Wu and those who wish to remain anonymous

TRUSTEES OF THE ROYAL

ACADEMY TRUST

Registered Charity No. 1067270

HONORARY PRESIDENT

His Majesty King Charles III

TRUSTEES

Batia Ofer (Chair)

Sally Tennant OBE (Vice-Chair)

President (ex officio)

Treasurer (ex officio)

Secretary and Chief Executive (ex officio)

Clara Amfo

Stefan Bollinger

Aryeh Bourkoff

Melanie Clore

Martin Ephson OBE

Pesh Framjee

Clive Humby OBE

Nicole Junkermann

Dame Carolyn McCall

Scott Mead

Siobhán Moriarty

Paulo Pereira

Lisa Reuben

Robbie Robinson

Bianca Roden

Ina Sarikhani Weston

Katy Wickremesinghe

The Hon William Yerburgh

EMERITUS AND HONORARY TRUSTEES

Lord Aldington

Susan Burns

Sir David Cannadine FBA

Sir Richard Carew Pole Bt OBE DL

Sir Trevor Chinn CVO

John Coombe

Elizabeth Crain

Lord Davies of Abersoch CBE

Sir Lloyd Dorfman CBE

Ambassador Edward E Elson

John Entwistle OBE

Michael Gee

HRH Princess Marie-Chantal of Greece

C Hugh Hildesley

Anya Hindmarch CBE

Susan Ho

The Lady Lever of Manchester

Sir Sydney Lipworth KC

The Rt Hon Lord Luce GCVO DL

Philip Marsden

Sir Keith Mills GBE DL

Ludovic de Montille

Lady Alison Myners

John Raisman CBE

Sir Simon Robertson

Maryam Sachs

The Hon Richard Sharp

David Stileman

Robert Suss

Peter Williams

CORPORATE MEMBERSHIP OF THE ROYAL ACADEMY OF ARTS

Launched in 1988, the Royal Academy’s Corporate Membership Scheme offers company benefits for staff, clients and community partners and access to the Academy’s facilities and resources. We thank all members for their valuable support and continued enthusiasm.

PREMIER

A&O Sherman

BNY Mellon

Cazenove Capital

Charles Stanley

Convex UK Services Limited (Convex Group)

Evelyn Partners

EY

FTI Consulting

JM Finn

JTI

KPMG LLP

Rothschild & Co

Sotheby’s

Van Cleef & Arpels

CORPORATE

Bloomberg LP

Chanel

Christie’s

Clifford Chance LLP

Edelman

Hakluyt & Company

HSBC

Marie Curie

Pictet

Rathbone Investment Management

Ltd

The Royal Society of Chemistry

Sisk

Teneo

Trowers & Hamlins

Value Retail

Weil Gotshal & Manges LLP

ASSOCIATE

Bank of America

Beaumont Nathan

The Boston Consulting Group UK LLP

The Cultivist

Deutsche Bank AG

Generation Investment Management LLP

Imperial College Healthcare Charity

Lazard

SMBC Europe Ltd

CORPORATE FOUNDING

BENEFACTORS

BNY Mellon

Index Ventures

Newton Investment Management

Sisk

Sky

CORPORATE PARTNERS

AXA XL

Bloomberg Philanthropies

BNP Paribas

Edwardian Hotels

Insight Investment

Viking

CORPORATE SUPPORTERS

Amathus

BNY Mellon, Anniversary Partner of the Royal Academy of Arts

Burberry

Claridge’s

Natalia Cola Foundation

Fortnum & Mason

Gide Loyrette Nouel

Hermès GB

House of Creed

L’ÉCOLE, School of Jewelry Arts, supported by Van Cleef & Arpels

Louis Roederer

Stewarts

Tileyard London