FASHION & THE PSYCHE

Mannequins in Maison Martin Margiela’s showroom Autumn-Winter 1994–95

Mannequins in Maison Martin Margiela’s showroom Autumn-Winter 1994–95

PREFACE

Kaat Debo & Bart Marius

STATEMENT #1

Elisa De Wyngaert

STATEMENT #2

Yoon Hee Lamot REPLICA

THE POWER OF THE DOLL

Elisa De Wyngaert

ASPECTS OF CLOTHING IN MENTAL INSTITUTIONS AROUND 1900

Ankele

AS

5 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS

Monika

ART OR ARTIFICE? FILTERING MAKEUP, MORALITY AND THE MIND

DRESS

SETTINGS

TOO HUMAN IN A POSTHUMAN AGE?

CYBORGS, AVATARS AND EMPTY SHELLS

INTIMACY

7 11 19 29 73 105 133 163 195

Lucy Moyse Ferreira DRESS

THERAPY WORKING WITH

AND FASHION IN PSYCHO-MEDICAL

Renate Stauss ALL

ON

Mara-Johanna Kölmel WHEN TEXTILE BECOMES SKIN ON CLOTHES AND

Yoon Hee Lamot

Comme des Garçons

Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body Spring-Summer 1997

6

6

KAAT DEBO BART MARIUS

PREFACE

In autumn 2022, MoMu Antwerp and Dr. Guislain Museum are joining forces for the first time for an ambitious dual exhibition entitled MIRROR MIRROR — Fashion & the Psyche, which examines the link between fashion, psychology, self-image and identity. What happens when a fashion museum and a museum about the history of and current attittudes towards psychiatry and mental health find common ground? Although our collections and subject matter are ostensibly very different, a collaboration between our two museums had been on the cards for quite some time. Those who think that one museum focuses on the body while the other deals with the mind, and that these are two separate entities that do not influence each other, ignore the complex interaction between these two components of our identity. In fashion, designers face ever-increasing pressure, dictated by the ever-faster pace of successive collections. During the coronavirus pandemic, the problem of this pressure and the forms of psychological suffering that it causes, for both established names and the newest generation of designers and fashion students, came to the fore. The growing focus on all things digital in our society, and thus also in fashion, also gave rise to new, often disrupted relationships between the body and the mind, and the body images that we apply in our society. The exhibition at MoMu revolves around the personal experience of the body. Themes include body dysmorphia (a body perception disorder); the layered meaning and history of human replicas such as dolls and mannequins; and the symbiosis between art, fashion and technology in the form of cyborgs and avatars.

Of course, not all clothing and style stem from a designer, whether they’re well known or not. Instead they are created in isolation, in the privacy of one’s living room, say, or in a mental hospital. In the past, psychiatric patients have sought to escape the world of psychiatry and also the uniformity that society attempted to impose on our sense of what is ‘normal’. The ‘madmen’ hoped to (metaphorically) flee the hospital in their own individual way, using their own clothes as a form of escape. In Dutch, the word for

madness is waanzin (literally: waan-zin or ‘madnesssense’). The word implies a creative value that can never be covered by the notion of mental vulnerability. Instead, this creativity assigns a necessary ‘sense’ or meaning to the madness. The ‘madness’, meanwhile, represents so much more than a small part of the identity or personality of someone who is suffering from psychosis. Madness can thus be meaningful, in the form of the artistic creativity that may give the patient a way out, an escape from the suffering. Vice versa, are we who do not suffer from psychosis willing to develop a language for ourselves to understand the rationale of madness? The exhibition at Dr. Guislain Museum highlights the joy and freedom that the ‘twisted’ mind brings us, even more than we expected. It brings together a group of exceptional artists, each of whom use clothes or textiles in their own way, to create a place for themselves in the world. Their creations are mostly hidden or occasionally revealed to just a handful of people. In some instances, they are also worn with pride on the catwalk that is the street.

MIRROR MIRROR — Fashion & the Psyche came about thanks to the enthusiasm of many. First and foremost, we wish to thank the curators of MoMu and Dr. Guislain Museum: Elisa De Wyngaert and Yoon Hee Lamot, respectively. Our sincere thanks also to graphic designer Paul Boudens, exhibition designers Bart Van Merode and Roel Huisman, and exhibition designer Tuur Demaegdt. We also wish to extend our gratitude to the many lenders, and the photographers and writers who contributed to this publication, as well as to Hannibal Books. Finally, we want to thank the two amazing museum teams that contributed their experience to this ambitious project, along with the volunteers, interns and production teams.

7 7

Director, MoMu — Fashion Museum Antwerp Artistic Director, Dr. Guislain Museum

10 10

Veronika Georgieva in collaboration with Stephen j Shanabrook Paper Surgery, 2010

REFLECTION REPLICA AVATAR

‘Fashion & the Psyche’, a story in two chapters and in two locations. That was the idea behind the close collaboration between two institutions, each with its own unique history, collection and expertise. After several long discussions with curator Yoon Hee Lamot of the Dr. Guislain Museum, we decided to examine the relationship between fashion and psychology from our own singular perspective.

The MIRROR MIRROR exhibition at MoMu places a strong emphasis on the body, telling a story in three parts.

11 11

DE WYNGAERT

—

Antwerp

ELISA

Curator, MoMu

Fashion Museum

48 48

49 49

Kenneth Ize Lookbook Autumn-Winter 2019–20

Diesel Save Yourself campaign by KesselsKramer Autumn-Winter 2001–02

50

50

Cindy Sherman

Untitled #304, 1994

Dirk Van Saene

I Feel Perfectly Terrible, 2021

Ceramic, tweed, cotton, horn and wood

51 51

Ward for female patients at the Großschweidnitz asylum, from: Johannes Bresler, ed., Deutsche Heil- und Pflegeanstalten in Wort und Bild (Halle an der Saale: Marhold, 1910)

72 72

ASPECTS OF CLOTHING IN MENTAL INSTITUTIONS AROUND 1900

This essay examines different aspects of the use of clothing in mental institutions at the beginning of the 20th century, putting a special focus on the patients’ point of view. For this I used medical records from German and Swiss psychiatric hospitals and self-testimonies from patients including letters and drawings.1 Following the original meaning of the word ‘text’, which is derived from the Latin textus meaning ‘fabric’ or ‘mesh’, I will blend the often sparse annotations in the documents like single threads into a multilayered fabric, unfolding the interwovenness of the individual perspectives and interventions. The structure of the essay follows different practices that relate to clothing in psychiatric hospitals at that time and were derived from the sources mentioned above. The different sections have the following headings: Handing over; Changing clothes; Ripping and undressing; Misusing and creating. 2

73 73

MONIKA ANKELE Researcher, Medical University of Vienna

‘Demands her clothes, wants to feel like a human being again for once.’

102 102

Simone Rocha

Spring-Summer 2021

Simone Rocha

Spring-Summer 2021

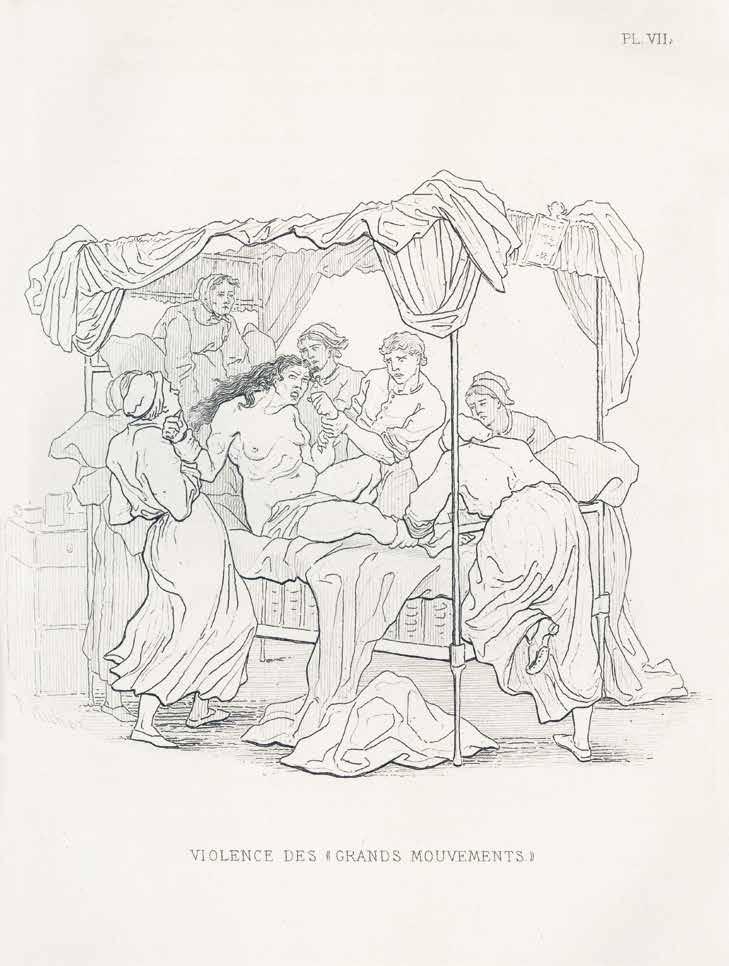

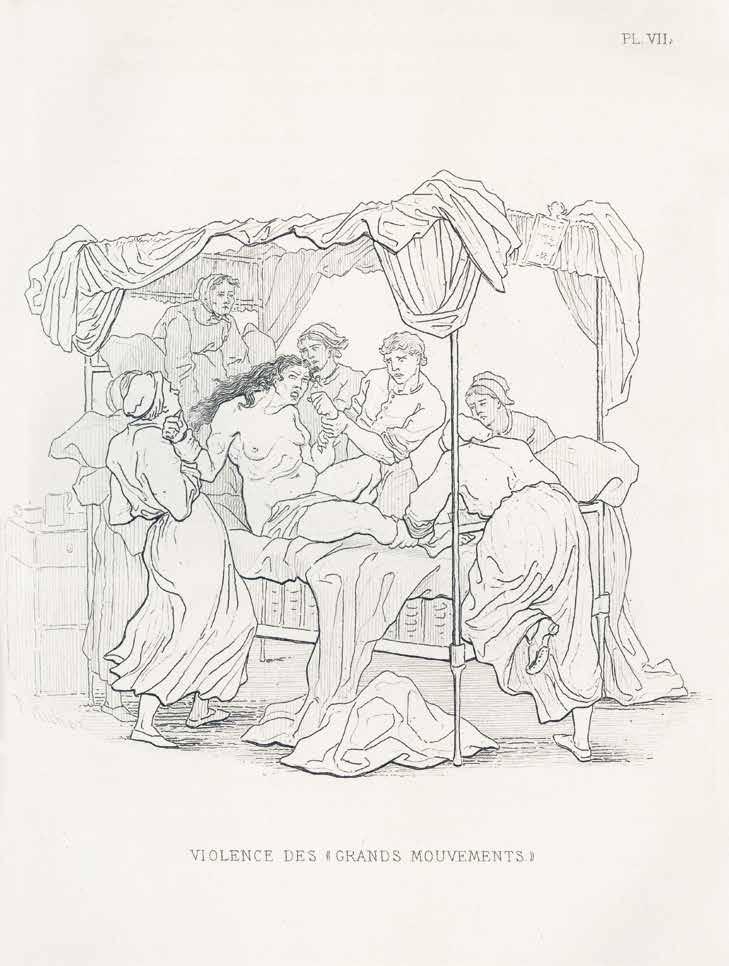

Variété de la grande attaque hystérique – Violence des ‘grands mouvements’, from: Paul Richer, Études cliniques sur la grande hystérie ou hystéro-épilepsie (Paris: Adrien Delahaye et Émile Lecrosnier, 1885)

132 132

RENATE STAUSS

DRESS AS THERAPY

WORKING WITH DRESS AND FASHION IN PSYCHO-MEDICAL SETTINGS

BETWEEN CONTROL, CURE, CARE AND CREATIVE PLAY

La Salpêtrière hospital, Paris, France, 1880: six attendants are trying to restrain a nearly naked ‘manic’ female patient, holding her by the wrists and ankles on a four-poster bed. A blanket barely covering her sex. Napa State Hospital, Imola, California, US, 1959: as part of ‘Therapy of Fashion’, a programme of grooming, dress design and self-presentation classes, an ‘expert instructs a patient in the proper method of applying cosmetics.’1 Without the presence of the nurse, one could not tell if the photograph was taken in a beauty salon or a mental hospital.

133 133

Professor of Fashion Studies, the American University of Paris

Guy de Longrée

Untitled, 2015

Felt tip pen on paper

154

154

155 155

Guy de Longrée Untitled, 2013 Felt tip pen on paper

THE CYBORGIAN REFORMATION

While the previous examples approach the increasing porosity between the human and the machine, or the digital and the physical, through figures that are ‘performatively produced as to-be-looked at, should-be-shared and can-bealtered,’28 the artist Lynn Hershman Leeson choses a different approach. Her Phantom Limb series humorously discloses how such performative acts of looking have become incorporated in technologies and have produced a panoptical body. The works from Phantom Limb stage the incorporation of female identity into media and technology by disclosing a male gaze. Female bodies merge with reproductive technologies including lenses, binoculars, television screens or cameras. It is the interplay between the body and its prosthetic that we encounter in Hershman’s work. Compared to Annlee’s fragile existence in Huyghe or Ohanian’s films, the posture of her female cyborgs is oriented towards the spectator and speaks of strength and self-confidence. As much as we gaze at them, they look back at us. They understand the power dynamics at play in the act of looking and mirror them back, thus reversing and transforming the way they are being absorbed, consumed, seduced and defined by the spectator. They are not mute objects but empowered subjects. ‘This work references the invasive nature of mass media and the ingestion of images that ultimately alters our mental projection of identity,’ Hershman writes in her text The Terror of Immortality.

From the perspective of today, her analysis strikes at the core of our contemporary internet culture. As early as 1994, Hershman pinpointed the internet, then called cyberspace, as an extremely important location for an expanded construction of the body and identity. ‘Before being truly plugged into or grounded in cyberspace, a person must create a mask. It becomes a signature, a thumbprint, a shadow, a means of recognition… Masks and self-disclosure are part of the grammar of cyberspace. They are the syntax of the culture of computer-mediated identity which can include simultaneous multiple identities… Cameras have become both eye cons and contact lenses,’ Hershman concluded. 29 Today, contemporary social media personalities such as the Kardashians have physically altered their bodies to appeal to their online audiences, thus taking Hershman’s 1990s notion of a ‘personal mask’ to its perverse limits. Such physical and digital edits of real-life celebrities are so heavy that CGI characters such as Lil Miquela somehow blend naturally into our feeds. While these digital avatars were originally modelled to echo the look of Instagram stars, it seems that these actual influencers increasingly present themselves as their digital counterparts. It is no secret that plastic surgeons now use Instagram apps such as Facetune, or images of both living and CGI personalities, to predefine their clients’ perfectly branded and homogenous-looking social media body.30

178 178

ALL TOO HUMAN IN A POSTHUMAN AGE?

179 179

Lynn Hershman Leeson Seduction, 1985 Gelatin silver print

208 208

209 209

Yasuyuki Ueno Untitled, 2010 Crayon on paper

Pascale Vincke

Untitled, undated Dry pastel on paper

230

230

Pascale Vincke

Untitled, c.1995 Dry pastel on paper

231 231

In MIRROR MIRROR – Fashion & the Psyche, MoMu — Fashion Museum Antwerp and Dr. Guislain Museum examine how fashion, psychology, self-image and identity are connected. The personal experience of the body is the main theme of this unexpected dialogue between visual art and avant-garde fashion. Featuring work by Ed Atkins, Walter Van Beirendonck, Noir Kei Ninomiya, Genieve Figgis, Genesis Belanger, Hussein Chalayan, Comme des Garçons, Joseph Schneller, Ezekiel Messou, Giovanni Battista Podestà, Helga Sophia Goetze and Yumiko Kawai, among others.

9 789464 366297

WWW.HANNIBALBOOKS.BE WWW.MUSEUMDRGUISLAIN.BE WWW.MOMU.BE

Mannequins in Maison Martin Margiela’s showroom Autumn-Winter 1994–95

Mannequins in Maison Martin Margiela’s showroom Autumn-Winter 1994–95

Simone Rocha

Spring-Summer 2021

Simone Rocha

Spring-Summer 2021