Introduction

We have seen Paris through the eyes of Hemingway and Balzac, the palettes of Chagall and Delaunay, the excesses of Henry Miller, the menus of Julia Child, the stars of Michelin, and the listicles of Fodors, Frommer’s, and Lonely Planet. But no one has ever seen it through the singular lens of the Exposition Universelle (Universal Exposition).

Paris is the physical memory of seven universal expositions that took place in the City of Light from 1855 to 1937. These expos left behind an urban diary of monumental landmarks — the Eiffel Tower, of course, but also the Musée d’Orsay, Grand Palais, and Petit Palais. The fairs left another inscription as subtle as the other was colossal: your suitcase today is an evolution of the trunk Louis Vuitton won a gold medal for at Paris’ Exposition Universelle in 1867. Gourmands eat Roquefort from Laurent Dubois, flâneurs lounge on bistro chairs, and everyone sips cup after cup of coffee at Le Procope and a thousand other bistros all because of a Parisian expo.

Nobody Sits Like the French: Exploring Paris Through Its World Expos tells those stories and many more. A champagne cocktail of travel guide and history, the book paints a Paris invisible to all but a handful of people on Earth who know that every time they sip a glass of Burgundy, drink from Baccarat crystal, admire a Monet or a Gauguin, and even enjoy the benefits of a working sewer system in the City of Light, they owe that experience to a world expo there.

Nobody Sits Like the French

Nobody sits like the French.

Wind the clock back one hundred years or so to a moment after the Charleston was gaining steam, but before movies were offering sound. You are in the savory nucleus of Paris, the corner of Boulevard Saint Germain and Rue SaintBenoît. Here is a venerable cafe that has been serving crepes and coffee since 1914 in its present location, a watering hole for a (mostly) civilized Serengeti of artists and thinkers as well as busy boulevardiers and slacking flâneurs during the period between the War to End all Wars and the Good War.

You’re sitting under the green marquee with lettering the color of Midas’ fingertips surrounded on all sides by the likes of Ernest Hemingway, Pablo Picasso, and James Joyce. Immense in their world as whales in a pond, they assembled at Les Deux Magots seeking inspiration and applause from the spirited (and spiritaided) knockdown debates and the bohemian atmosphere that flooded the cafe. Listen closely and you can hear Hemingway stage whispering his poetry, and see him working feverishly on The Sun Also Rises, stained with the blood and smoke of the Great War’s trenches. A few feet away and liquored up on Swiss wine, James Joyce is picking a fight (then hiding behind Hemingway’s bulk) while Pablo Picasso is hitting on his future muse Dora Maar there. The mean girls of Surrealism, Max Ernst, Joan Miró, and Man Ray, hold court at their table by the cafe entrance, where, between scarfing down croque monsieurs and macarons and working on their manifesto, they hiss insults at anyone whose looks they don’t like. Go back even further in time and you can glimpse those twin poets of the damned, Paul Verlaine and

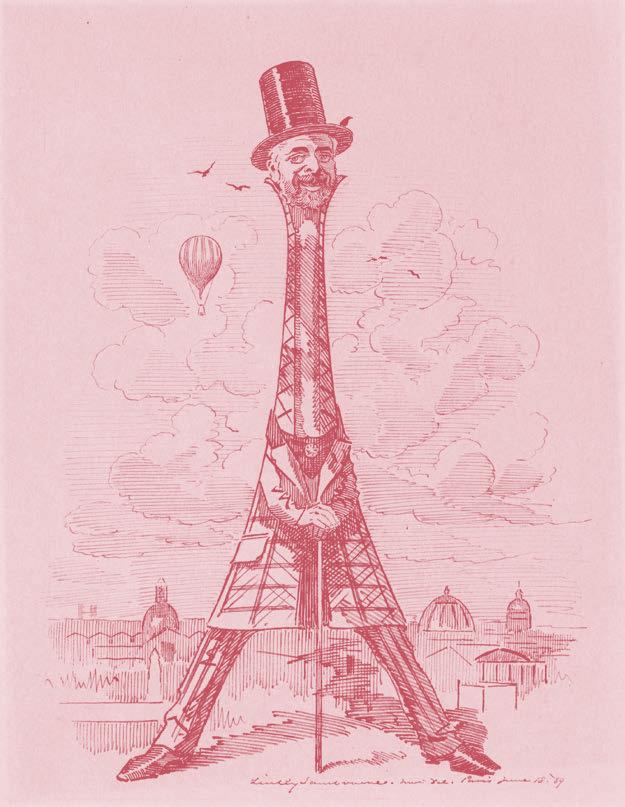

The Eiffel Truth

In 1886, men who were likely conversant with the electric light and the phonograph but perhaps wishing they lived in an age before electricity was being broken in like a wild horse and the voices of the dead could be heard, convened. They sat down to select an architectural marvel that would serve as the ethereal anchor, a manmade northern star, for the Exposition Universelle that would take place just three years later. You know, of course, they picked Gustave Eiffel’s creation. What you might not know is that the spire that was ultimately selected to be built on the Champ de Mars was a magnitude of order (or two, or three magnitudes) less audacious than the most peculiar entries in the contest. Among the 107 to 700 suggestions (depending on who’s doing the counting) for the centerpiece, one was for a tower shaped like a watering can whose nominator assured judges that the flask “would be useful on sultry days”.

The other, a tour de force of insanity, was for a 1,000 foottall guillotine that would have commemorated France’s Headless Horseman history. Aka the ‘National Razor’, the guillotine was used to execute between 15,000 and 17,000 unfortunates during the French Revolution’s Reign of Terror. In the eyes of some, the expo was going to mark the anniversary of this bladed savagery with the world’s biggest party. Accordingly, several countries — Belgium, Spain, Portugal, Russia, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and AustriaHungary — RSVP’ed to their invitation to the expo that year with a hard ‘No’. Being monarchies, they weren’t eager to participate in an event celebrating the centennial of separating royals from their heads. (It probably wouldn’t have helped to nitpick that ‘only’ 8.5 percent of those liquidated were aristocrats.) Little

How many cities can say they were built by someone called The Demolisher?

The name alone sounds like it’s from the first tier of Marvel Universe antagonists, the kind of scheming heavy who would have set fire to the Atlantis of myth, the Gotham of Batman, or the Emerald City of Dorothy, the Tin Man, the Scarecrow, and the Cowardly Lion.

But it wasn’t any of those fairytale settings; it was Paris. In 1855, Emperor Napoleon III may have been lord of all he surveyed in the City of Light but what he saw of the sprawling 2,400 yearold landscape wasn’t a jewel in his crown. Threequarters of Parisians were besieged not by the English, the Habsburgs, or the Holy Roman Empire, but by the more traditional foes of poverty, disease, and overcrowding.

Impressed by London’s widespread parks and effective sewers and Vienna’s broad boulevards, Napoleon III turned the upcoming world exposition — the first of seven in Paris — into a catalyst for the transformation of the entire city. It was a showpiece of urban planning that was reviled at the time by the doddering statusquo crew, just as the Eiffel Tower was 34 years later.

Enter GeorgesEugène Haussmann, a civil servant (later he was unofficially ordained ‘Baron’) who had no training in architecture but was armed with the tenacity of a pitbull and the vision of an eagle. Haussmann wasn’t just the standardissue riskaverse bureaucrat, though; he was the kind of takecharge guy who believed Paris’ maze of streets was as outdated as serfs and codpieces, and imagined majestic boulevards taking their place. When the minister of the interior, Victor de Persigny, interviewed candidates for the job, Haussmann towered above all the others, less for

Lights, Camera, Overacting

Sarah Bernhardt was a human exclamation point. The notorious stage actress was equal parts gifted liar, fair-to-middling concubine, and a premier synonym for ‘overwrought’. But her most deserved stardom has been buried in the historical version of a pauper’s grave. It came through her appearances at the Parisian world expos where she hijacked a hot-air balloon, pioneered biomorphic sculpture, and pushed the fledging motion picture industry into the future.

By the time of the 1878 Exposition Universelle, Sarah Bernhardt didn’t need to be more famous. The girl who wanted to become a nun had instead become an actor after the Duke de Morny, Napoleon III’s half-brother, and one of her mother’s many paramours, arranged for her to enter the Paris Conservatoire, the government-supported school of acting, in 1860 when she was 16. Had Meryl Streep been alive then, the Conservatoire would not have considered her the next Meryl Streep. Yet, after signing with the Odéon theater in 1866, she took off in a six-year sprint to fame, first as Anna Damby in the 1868 revival of Kean, by Alexandre Dumas père ( père in this case means the Dumas who wrote The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers), followed by starring turns as Cordelia in Le Roi Lear and the minstrel Zanetto in François Coppée’s one-act verse play Le Passant (The Passerby). Mark Twain sang her praises and Oscar Wilde penned his play Salome in French just for her. She didn’t so much push gender boundaries as rudely shove them aside, playing saints (Joan of Arc, Phaedra), sluts (Cleopatra), and slackers (Hamlet). An A-plus student of affectations, she wore a stuffed bat in her chapeau and was photographed in her bed/coffin lined with white satin, love letters, and bouquets of flowers. She owned an alligator named Ali-Gaga

Lights, Camera, Overacting

How to Make an Entrance

Every great fairy tale begins with an entrance.

Sometimes it’s through a forest, a passage underground, a route beneath the sea, or even above the sky. In The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe an enviously oversized closet transports naïve children to a land where a large member of the cat family shares power with the Roman god of wine. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland began when she bungee jumped into a rabbit hole. Harry Potter’s journey to Hogwarts kicks off on London’s Platform 9¾. They’re all different, these entrances, but what they have in common is that they’re all paths that take us from the ordinary to the extraordinary.

The world expos in Paris had them too. and they could be as transportive as Jack’s beanstalk or the evil queen’s magic mirror, portals to a world this close and yet a galaxy far, far away from what you know.

Expos even pioneered entrances in their most blandly familiar form: turnstiles. Few of us would ever suspect that when they enter an NFL football stadium or a Taylor Swift concert through turnstiles, they’re using a line management device originally built for the Exposition Universelle of 1855 in Paris. While they brought order to impatient throngs pushing and shoving their way into the expo, turnstiles were not without substantial drawbacks. Women’s ballooning petticoats, for example, often became ensnared in the crowd controlling contraptions, a frustratingly common occurrence satirized below by the painter, sculptor, and printmaker Honoré Daumier. In his onthe spot caricature, the renowned illustrator likened the turnstile to a tourniquet that trapped extravagantly attired attendees in its metal limbs.

Place of Workship

Shortly after Christmas in 2023, the Eiffel Tower’s four hundred unionized employees went out on strike on the centenary of its creator Gustave Eiffel’s death. The timing wasn’t coincidental. Concerned that the aging pillar’s structural needs were being blithely ignored, the striking union leaders claimed the Tower’s operating company was ‘heading for disaster’.

It was one of the few moments in the nearly two centuries of expos when the nameless ones who built or maintained their wonders — e.g., the Musée d’Orsay, the Grand Palais, and Petit Palais — become visible to us, if only for the briefest of moments. Normally, they are as nameless as the those who lugged the limestone blocks of the Great Pyramid or heaved the slabs of sandstone to Stonehenge.

But there is one church in all the world that gives these uncelebrated artisans their overdue recognition, and it’s directly because of world expos: NotreDameduTravail.

But first, a little back story. From the first world’s fair in London — The Great Exhibition in 1851 — the expos exalted royalty, capital, management, manufacturers, owners, everyone but the actual builders of those gaudy fairs. In 1855, the first of Paris’ World Expos planned on giving the craftsmen, the designers, and the workers behind the thousands of products and machines displayed the round of applause due them. But factory owners in France saw no point in singling out their best workers, leaving them vulnerable to being poached by competitors offering more pay and better conditions, and what Aretha Franklin would call r e s p e ct. In that era, it was perhaps what the French would call a fait accompli: Despite

NOBODY SITS LIKE THE FRENCH

EXPLORING PARIS THROUGH ITS WORLD EXPOS

Words: Charles Pappas

Image selection: Charles Pappas

Final editing: Hadewijch Ceulemans

Graphic design: doublebill.design

Front cover illustration: © IStock – Cecil Aldin

D/2025/12.005/5

ISBN 9789460583797

NUR 680

© 2025, Luster Publishing, Antwerp lusterpublishing.com info@lusterpublishing.com

Subscribe to our newsletter for new book alerts and a look behind the scenes:

Printed in Europe.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher. An exception is made for short excerpts, which may be cited for the sole purpose of reviews.