1.Integrations

The Cockpit / Creek Vean House / Murray Mews Houses / Skybreak

Fred Olsen Operations Centre and Passenger Terminal / Air-Supported Office, Computer Technology / Newport School / IBM Pilot Head Office / Willis Faber & Dumas Headquarters / Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts / Foster House, Hampstead / Renault Distribution Centre / Nomos Table and Nomos Desking System

2.Urban Systems

Historical

Carré d’Art / Reichstag, New Parliament / Great Court, British Museum / Hearst Tower / Chesa Futura / Kogod Courtyard, Smithsonian Institution / Restoration and Library, Free University of Berlin / The Sage Gateshead / Zayed National Museum / Bloomberg / Nouveau Chai and Wine Cellar, Château Margaux / Maggie’s Manchester

Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Headquarters / Century Tower / Millennium Tower / New World Trade Center / Commerzbank Headquarters / 30 St Mary Axe / Cepsa Tower / The Troika / 425 Park Avenue / Comcast Technology Center / 270 Park Avenue

Trafalgar Square Masterplan / More London Masterplan – PricewaterhouseCoopers Headquarters / Redevelopment of Marseille Vieux-Port / West Kowloon Cultural District / Apple Piazza Liberty / Kharkiv Masterplan

Preface 8 Laurent Le Bon and Xavier Rey Norman Foster: Ecosophy of Systems 12 Frédéric Migayrou Living Architectures 36 Norman Foster with Frédéric Migayrou Inspirations 48

56 Team 4 58

Housing / High-Density Housing / Reliance Controls Factory Environmental Control 68

House / Waterfront

With Richard Buckminster Fuller 84 Samuel Beckett Theatre / Climatroffice / Autonomous House

90

Contexts

92

Vertical City 114

Public Spaces 130

Contents

Stansted Airport / Hong Kong International Airport / Terminal T3, Beijing Capital International Airport / Queen Alia International Airport / Kuwait International Airport / New International Airport Mexico City / Millennium Bridge / Millau Viaduct / Torre de Collserola / Haramain

Regional Planning Study / Lycée Albert-Camus / Électricité de France Regional Headquarters / Great Glasshouse, National Botanic Garden of Wales / La Voile / Elephant House, Copenhagen Zoo / London City Hall / Masdar City / Droneport / Vatican Chapel, Pavilion of the Holy See / SkyCycle / ENEL Power Pylons / Nuclear Microreactors

Design for Living, 1969

Social Ends, Technical Means, 1977 Foster Associates, 1991

Bucky and Beyond, 2001

History helps us realise that the only constant is change, 2019

Authors of project notes : Camille Lenglois (C.L.), Julia Motard (J.M.), Céline Saraiva (C.S.), Yûki

‘The only constant is change’ 140 Philip Jodidio Drawings and Sketches 154

in Perspective 174 Networks 176 London

High-Speed

Metro / Canary Wharf Underground Station / Crossrail Place Mobilities 194 American Air Museum / McLaren Technology Centre / Repsol Service Stations / Yacht Club de Monaco / Izanami Motor Yacht / YachtPlus Fleet Ecologistics 200 Gomera

Dimensions of the Globe 216 Apple Park / DP World Cargospeed Hyperloop / Spaceport America / Lunar Habitat / Mars Habitat Selected Writings of Norman Foster 228

3.The Earth

Rail / Bilbao

The Nuclear

Projects by Norman Foster 248 Selected Bibliography 256 Compiled

Yoshikawa

Option: Energy Futures, 2022

by Frédéric Migayrou and Yûki

Yoshikawa (Y.Y.), Anne-Marie Zucchelli (A.-M.Z).

Norman Foster: Ecosophy of Systems

‘Etymologically, the word “ecosophy” combines oikos and sophia, “household” and “wisdom”. As in “ecology”, “eco-” has an appreciably broader meaning than the immediate family, household, and community. “Earth household” is closer to the mark. So an ecosophy becomes a philosophical world-view or system inspired by the conditions of life in the ecosphere.’

Arne Næss1

When we think of the work of Norman Foster, it is his most spectacular projects that come to mind, the ones that seem to epitomise the image of a city, a region, or that, more simply, have changed the shape of a site or the configuration of a place. And the list is a long one. We are talking of an architect who has worked in most countries of the world and has undertaken a huge diversity of projects, most of which have impacted on the very structure of the urban fabric. Airports, transport networks, headquarters of international companies, public buildings, major works of art, urban development programmes, museums – Norman Foster has explored the whole complexity of industrial society through hundreds of projects, some only planned, some realised, in every part of the globe. He has constantly adapted the size and composition of his practice, founded in 1967, to the evolution of the world’s economy, which had centred on the United States during the post-war period, but then opened up to China, Russia, India and South America. In the face of this globalised world, Norman Foster has developed a practice that has grown from its base in London to form a network of international offices that is better able to respond to multiple commissions. Unlike those large anonymous firms that produce equally anonymous projects all across the globe, and also unlike those architects whose names have almost become brands, Norman Foster has created a practice that has preserved its own identity as a global enterprise constantly open to new research and innovation. ‘Foster + Partners is coming to resemble not so much any previous large architectural practice,’ explains Deyan Sudjic, ‘but more a cross between a leading school of architecture and a global research-based consultancy.’2

Frédéric Migayrou

What has made the practice so unique is the configuration it adopted when moving to Fitzroy Street in 1971 – one which implied a collegial approach and was mirrored in its functional and spatial organisation. Foster has described it as ‘[f]irst of all the studio. An open, flexible space; a range of activities; changeable; a test-bed in some respects ... the idea of architects, engineers, economists coming together in a dynamic relationship, changing hats and changing roles in a shared endeavour.’ 3 Even during the period when he was collaborating with Richard Buckminster Fuller, Foster was developing a new type of structure for his practice that seemed to echo the ideas of Stafford Beer, the author of Brain of the Firm (1972). Beer proposed innovative forms of management based on collective experience and learning, and a democratic approach to decision-making and control directly inspired by cybernetics, which he dubbed ‘syntegration’, a portmanteau of two concepts initiated by Buckminster Fuller, ‘tensegrity’ and ‘synergy’. The formalisation of this way of thinking about the organisation, which implied a complete overhaul of design logics and methods, is evident in the development of the Foster Associates practice, with its adoption of a participatory approach that changed not only the nature of the architect’s role, but also the practice’s relationship with its many stakeholders and clients. This involved rethinking the functioning of an architectural practice in a state of perpetual evolution –one which has to face up to the social, economic and ecological problems of a world in flux – and this structuring principle underlies the activities of Foster + Partners to this day.

In much of his writing, Norman Foster dispenses with the traditional image of the architect-creator, the academic function of the author, and the notion of the architectural object. He instead foregrounds a synthetic vision of the organisation and its infrastructure. He attributes the origin of this approach to his early years, when he was a young teenager attracted by a complex world of gadgets, which he would see represented in his Eagle comic. It was during his youth in Manchester that he discovered architecture, both in the streets he frequented – he admired, among others, the Lancaster Arcade (1871), Manchester Town Hall (1877) designed by Alfred Waterhouse, and the Daily Express Building (1939) by Owen Williams – and in the books of Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier. The critical interest that his early surveys of the mechanism of mills ( Post Mill at Bourne , 1958) still attracts today shows that the concepts that he developed at that time would be incessantly revised and remodelled as his career progressed. While he travelled in Italy and Denmark, discovering the work of Jørn Utzon and Arne Jacobsen, he received a Henry Fellowship, enabling him to study at Yale University, where he met Richard Rogers. The teaching of the then head of the architecture department, Paul Rudolph, strengthened Foster’s structural thinking about space, which resulted in a style of drawing that used perspectival sections – the first marker of what would become a whole new methodology. ‘Many of these drawings,’ Foster explains, ‘especially the perspective sections, would encapsulate in a single image the range of Rudolph’s concerns as an architect. There was his quest to define and model space with light and planar surfaces.’ 4 The charismatic Professor

13

Team 4, 1966

Above: Anthony Hunt, Frank Peacock. Below: Sally Appleby, Wendy Foster (Wendy Cheesman), Richard Rogers, Su Rogers (Su Brumwell), Norman Foster, Maurice Phillips Norman Foster Foundation Archive

Living Architectures

Norman Foster with Frédéric Migayrou

Frédéric Migayrou: Norman Foster, you have worked on many types of programs, including airports, transportation systems, museums and universities, and for each of them, the question of locality is always present. What is the relationship between the global vision of the architecture that you develop, and the specificity of each project’s context?

Norman Foster: Trends are global in cities. For example, the relationship between mobility and public space – whether it’s Seoul, Boston or Madrid – the trends we are witnessing are the same. We are seeing road systems being either partly buried or diverted, and more space given over to people and nature. But what happens on the ground relates to the particular place; every city is different. It’s the same with an individual building. It has components which come from all over the world, but the way they come together responds to a specific brief. The challenge is to maximise the differences, rather than encouraging homogeneity. The answer is to encourage local DNA and culture, to be sensitive to them, and to have the best of both worlds. In short, each project should be of its place.

How did this vision of architectural and urban complexity first take shape? You often mention your discovery of the technical complexities of locomotives and aircraft at a young age through drawings in Eagle magazine, or your exposure to Manchester’s architecture, for instance the Barton Arcade and Alfred Waterhouse’s Town Hall, or Owen Williams’s Daily Express Building. How was your original understanding of architecture arrived at?

As a child, I was drawn to magazines and books which showed the cutting-edge technologies of the time, with drawings that revealed their inner components. When I made my first drawings at the Manchester School of Architecture, I chose not to

restrict myself to just plans, sections and elevations, which are two-dimensional. I was also taking those buildings apart, seeing how they work and drawing them three-dimensionally. While my drawings have become more sophisticated, they still seek to explain the inner workings and systems of a building.

After receiving your master’s degree, you obtained a scholarship to study at Yale University, where you met Richard Rogers. The influence of architects such as Louis Kahn, Paul Rudolph and Serge Chermayeff was to prove decisive, as was your discovery during a trip to California of new construction principles at the Case Study Houses designed by Craig Ellwood and by Charles and Ray Eames, and also in Ezra Ehrenkrantz’s School Construction Systems Development (SCSD). How do you view these early influences today?

I think influences can either be conscious or subconscious – and we’re all a product of them. If I think about my first experience of going into the School of Architecture, which was located in the Louis Kahn Building at Yale University Art Gallery, I recall the famous picture of Kahn looking up at the diagrid ceiling. That ceiling could never have happened without the pioneering work of Richard Buckminster Fuller, one of my early mentors, whom I later went on to work with on several projects during my early career.

Another influence at that time were the Case Study Houses, which had an extraordinary glamour to them. They were quite utilitarian, using standard off-the-peg items, but these were being put together to create beautiful architecture. During the early days of practice, our work on school systems owed a debt to the California SCSD pioneered by Ezra Ehrenkrantz, which was only made possible because he had been in the United Kingdom immediately after the Second World War, when schools were being industrialised. So, there are always these links to the past but, of course,

37

We are all a product of influences that can inspire our work. Creatively, we might be consciously aware of them, or they might be buried in our subconscious. They can be people (parents, partners in life or work, collaborators, mentors, writers) or places (cities, squares, boulevards, parks, bridges, buildings) or objects (machines, vehicles, aircraft, sculptures, paintings). All that is tangible in the visual world is subject to design, by nature or by humans. Which is why I see no distinction between the creative worlds of objects, art and architecture – for me they are all one seamless whole.

Inspirations

48

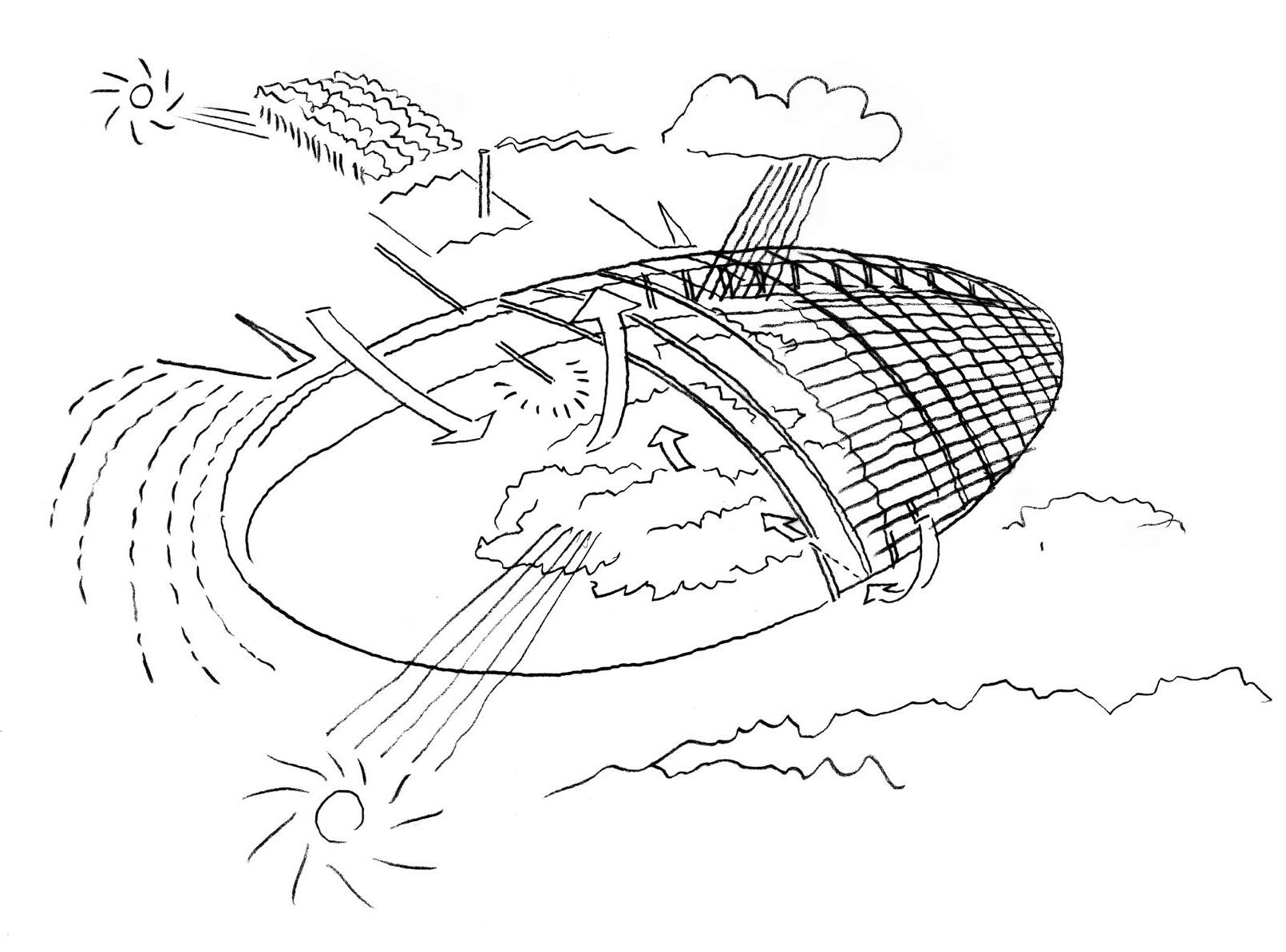

Norman Foster

Norman Foster Inspirations

2017

Pencil on paper

29.7 × 20.8 cm (11 5/8 × 8 1/8 in)

Norman Foster Inspirations

2017

Pencil on paper

29.7 × 20.8 cm (11 5/8 × 8 1/8 in)

Norman Foster Foundation Archive

‘The only constant is change’

Philip Jodidio

It is difficult to understand how some architects emerge from their profession to become the inventors and leaders who make perceptions about design, construction, aesthetics and, finally, architecture itself evolve. A select few set patterns followed or imitated by others. It is indeed rare to come across a single figure who has not only designed and built significant projects across the world but has also been able to firmly control increasingly large offices. Norman Foster is such an architect, one who has changed the profession, built an office that has nearly 1,800 employees with nineteen studios worldwide, and maintained the curiosity and drive that have characterised him since his early years.

Norman Foster was born in 1935 in Reddish, north of Stockport, in Greater Manchester. He grew up in a working-class environment, first exposed to engineering and design by his father’s work as a machine painter for the electrical engineers Metropolitan-Vickers. He left school at sixteen and worked as a clerk at Manchester City Hall. After completing his military service in the Royal Air Force in 1953, he became an assistant to the contracts manager at the architectural firm John Beardshaw and Partners (Manchester). His aptitude for drawing earned him a position in the firm’s drawing department. Funding his studies with part-time work, Foster studied from 1956 at the University of Manchester’s School of Architecture and City Planning.

Foster is unusual in that he has consistently sought to identify the forces that played on him and influenced his sensibility and creativity. Although many architects would not cite such factors, the influences of art and nature are two important and early parts of his thought process. He explains:

‘Growing up in a semi-industrial suburb of Manchester, I discovered the work of the artist L.S. Lowry, whose paintings seemed like the very essence of a Northern urbanity with their long lines of brick row houses interspersed with factories and chapels – all without a trace of greenery. This early interest would develop into a lifelong fascination with issues of the city. But that background also provoked an appreciation of the countryside and nature – my escape route by bicycle at weekends was to discover the lush countryside of Cheshire and the Peak District of Derbyshire. I loved the contrast between these two worlds of nature and urbanity – and I still do.’1

To this day, Norman Foster keeps an urban view by Lowry near his bed.

The connectiveness of things

Foster graduated from the University of Manchester in 1961, receiving a Henry Fellowship to continue his studies at Yale University, where he met Richard Rogers. His time at Yale was seminal in more than one way. Robert A.M. Stern, a former dean of the Yale School of Architecture (1998–2016), wrote, ‘Foster’s decision to go to Yale was not easily arrived at. But he found Yale to be a liberating place, alive to the possibilities of architecture as an art and to the cross-currents of prevailing styles, ideologies, and passions.’2 Foster’s experience in the United States helped to awaken his remarkable awareness of the connectiveness of things. ‘America also presented a rich imagery of artefacts, which continue to fascinate me,’ he says. ‘The juxtaposition of the Airstream caravan, Ford station wagon and Colorado wilderness alongside the Apollo 17 module, moon buggy and lunar landscape is evocative of autonomy and liberation – a short thirty-year hop in time between the earthbound and a 239,000-mile [385,000-kilometre] leap into space. Different constraints and different responses, the smooth wrap-around envelope of the Airstream in contrast with a spindly articulated aesthetic of the module. There are some obvious links here to our work with Buckminster Fuller on autonomous dwellings.’3 In 1994, he also stated, ‘Yale opened my eyes and my mind. In the process I discovered myself. Anything positive that I have achieved as an architect is linked in some way to my Yale experience.’4

The right stuff

Returning to England, Norman Foster was one of the founding partners of Team 4 together with his Yale classmate Richard Rogers, and two sisters who were also architects, Wendy Cheesman (who became Wendy Foster in 1964), and Georgie Wolton. Although it was short-lived (1963–67), Team 4 set in motion many of the themes that re-emerged in the later work of Foster. One of their projects, the Reliance Controls Factory (Swindon, UK, 1965–66), announces an integrated approach not only to the technical, programmatic requirements of the client, but also provides an innovative approach to social issues. This points in an active way to one unusual strength of Foster – the continuity of his organisational and design patterns, but also of his points of focus, be they material or immaterial. He and his wife created the firm Foster Associates in 1967, just after the dissolution of Team 4. Today, Foster seeks to link that period to the current, much larger firm Foster + Partners:

141

1920 Oil on

43.5

55

Private collection

Laurence Stephen Lowry Unfinished street scene, verso of A Lancashire Village

panel

×

cm (17 1/8 × 21 5/8 in)

I am never without my sketchbook and pencil, so drawing and writing is a way of life. For me, design starts with a sketch, which may look like the result of sudden inspiration but is likely to follow a total immersion in the issues leading to it. Someone once said that if I am asked a question then I will answer with a sketch. I admit to sometimes finding the drawn image faster and more to the point than articulating words. It can be part of a process of self-interrogation – making the imagination visible through the power of a line. The line may be the hasty, spontaneous scribble or the longer and more deliberate process of drawing with pencil, ink and colour. The pencil, as a tool, was once as indispensable to the process of design as today’s computer. However, no machine is able to replicate the tactile pleasure in the movement and friction between a pencil and the surface of a clean sheet of paper – I find that one of the most human and joyful of sensations.

Norman Foster

Drawings and Sketches

154

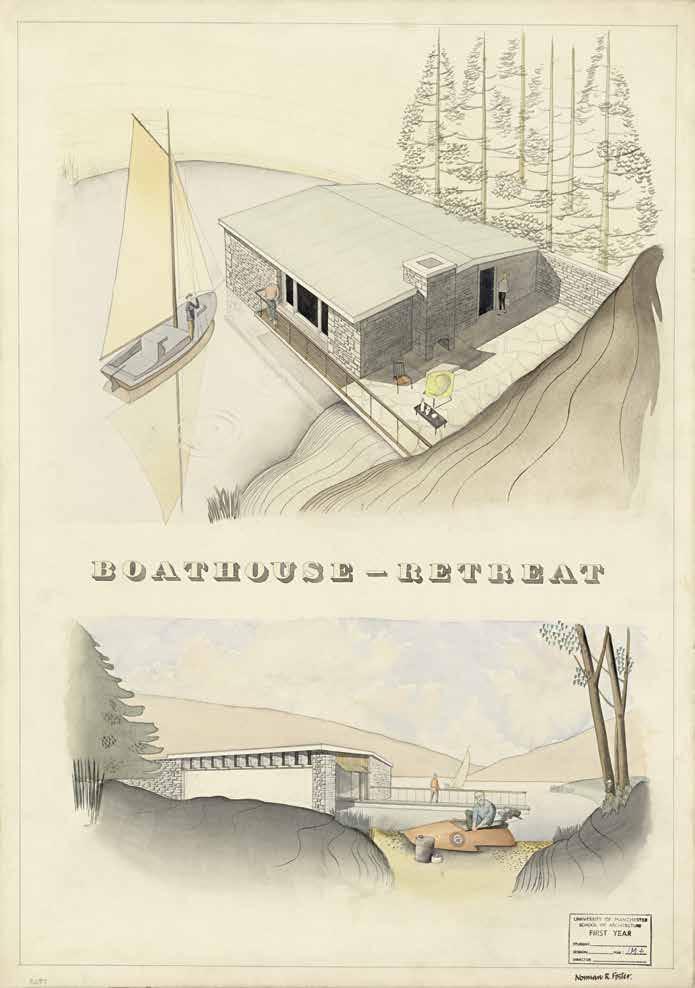

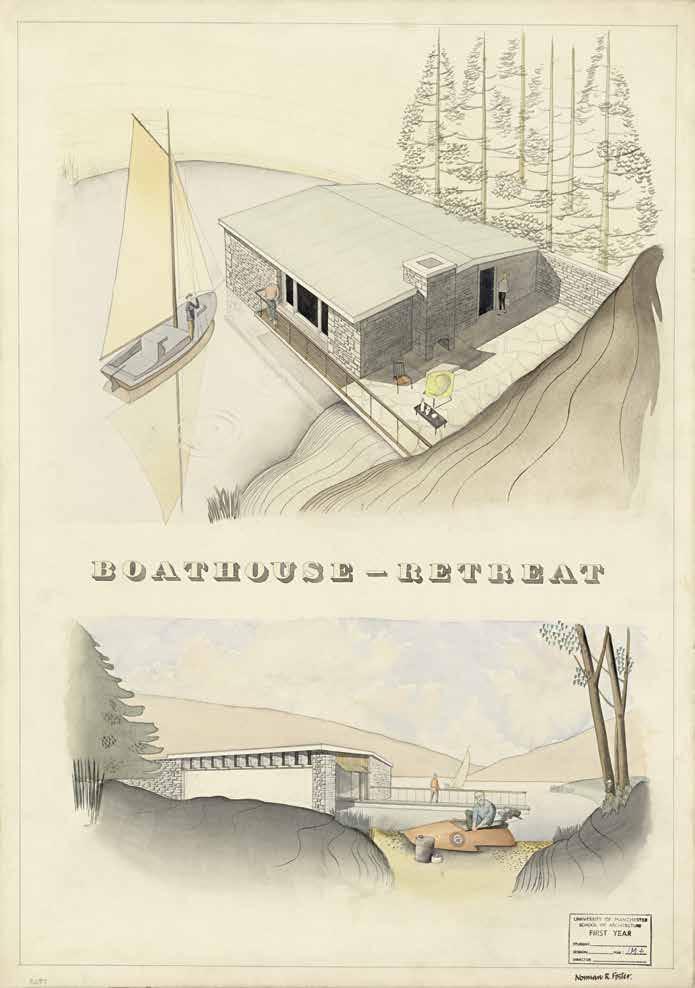

1956 Ink, pencil and watercolour on board 75.8 × 53.5 cm (29 7/8 × 21 in) Norman Foster Foundation Archive

Norman Foster Boathouse and Retreat

The Earth in Perspective

Norman Foster is an architect of mobility within networks. The unlimited extension of transport and communication systems, the unbridled expansion of industrialised societies and the advent of the technosphere have led him to take account of their resulting impacts on the biosphere. His design for London Stansted Airport prefigured those of his many major airport hubs, notably Hong Kong, Beijing and Mexico City, which are envisaged as transfer spaces optimising the flow of international traffic. Rationalisation of energy, integration into local areas and an economy in the construction processes are all key to the implementation of such infrastructures, whether they are engineering structures (Millau Viaduct, Millennium Bridge), maritime terminals (Monaco, Hong Kong) or rail transport projects (Bilbao Metro, Canary Wharf Underground Station, Haramain High-Speed Rail). Norman Foster has always associated the evolution of technology with a positive ecology; each of his projects is based on the idea of sustainable development, especially those related to droneports and nuclear microreactors. F.M.

175

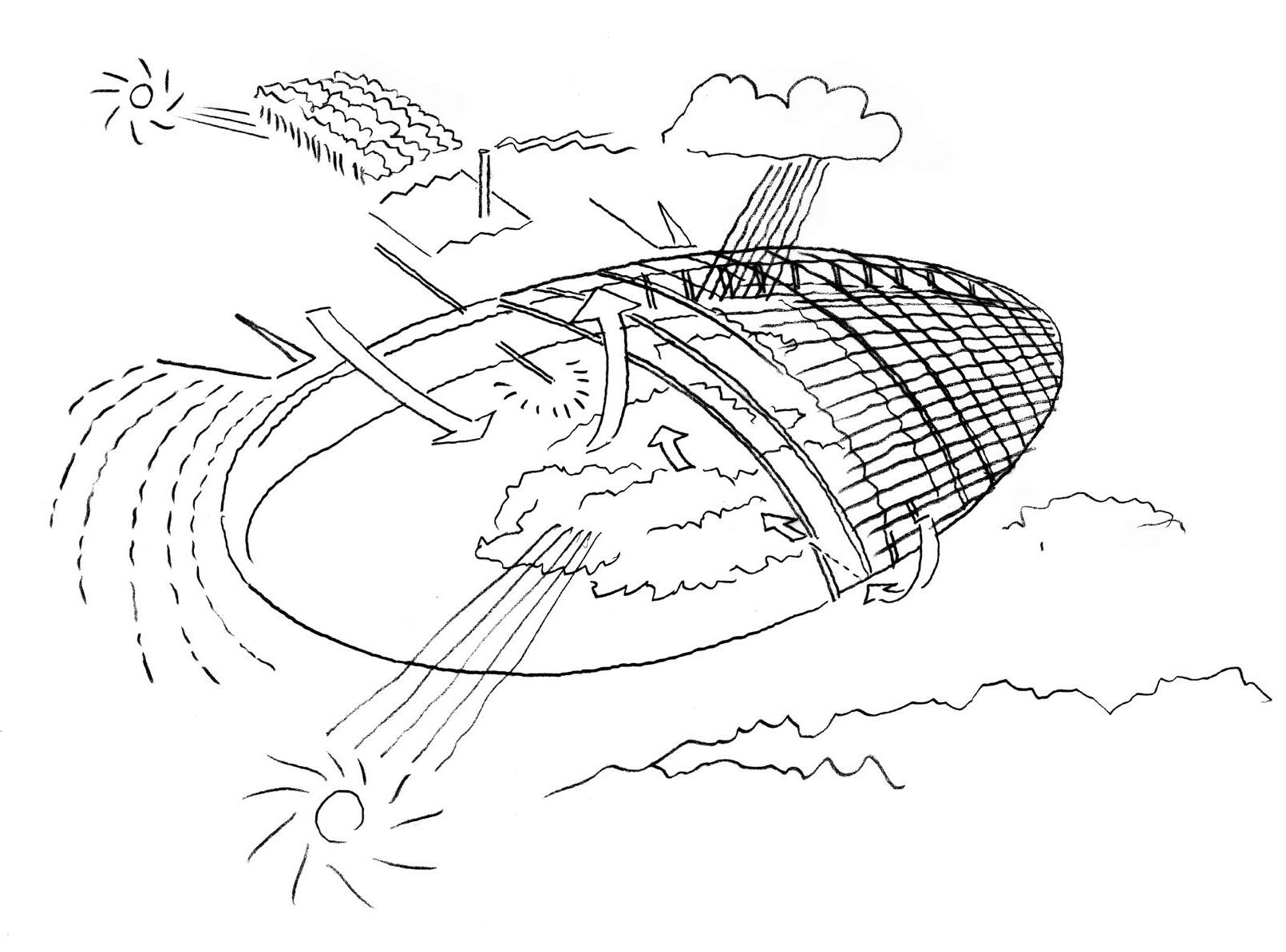

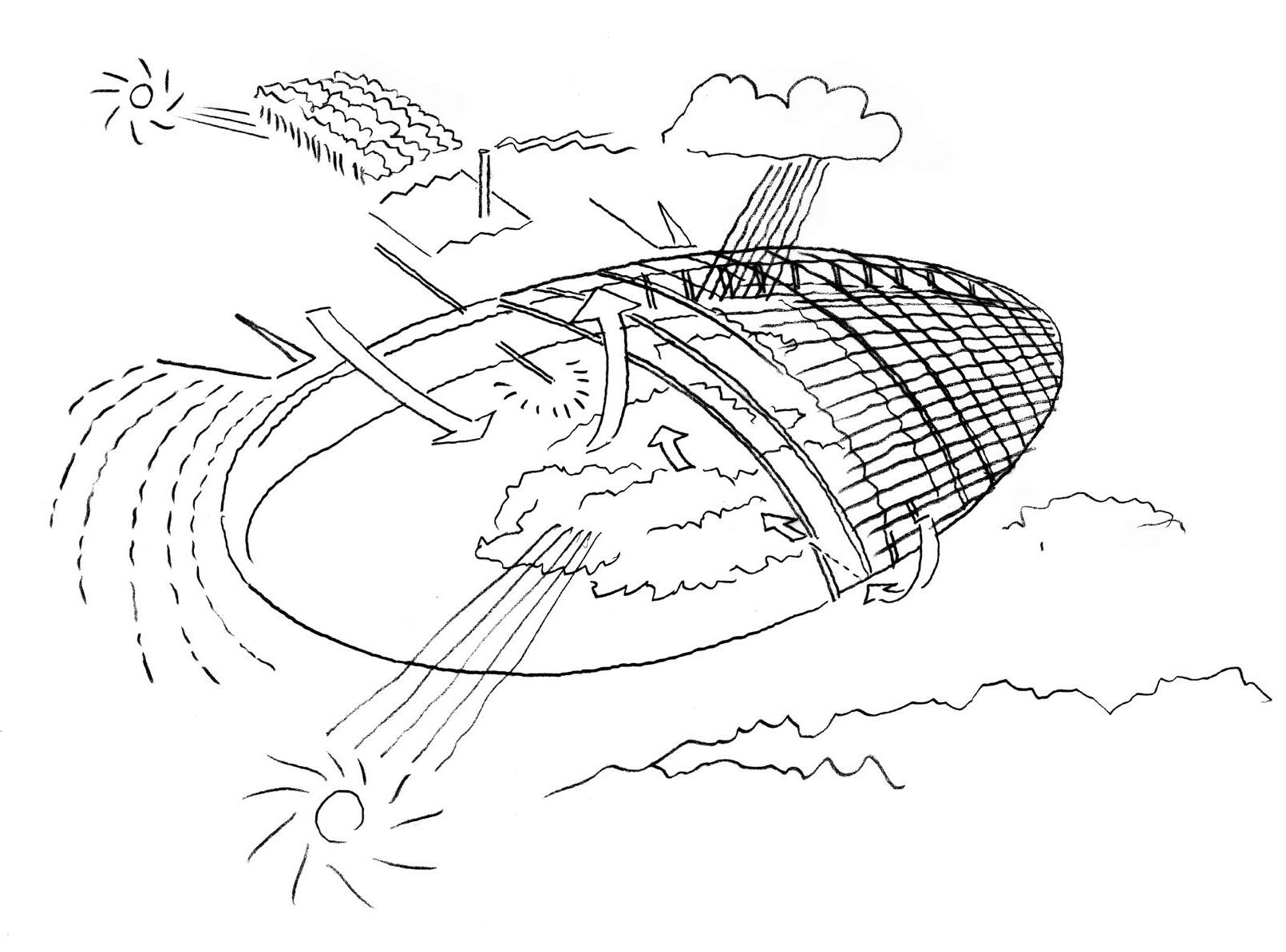

Foster +

Great Glasshouse, National Botanic Garden of Wales Llanarthney (UK) 1995–2000 Sketch by Norman Foster, n.d. Pencil on tracing paper 21 × 29.6 cm (8 ¼ × 11 5/8 in) Norman Foster Foundation Archive

Partners

Norman Foster is a globally recognised figure in architecture. His practice has created projects around the world, many of which have profoundly transformed the cities and landscapes in which they reside.

This new monograph, published in partnership with the Centre Pompidou, presents more than 80 of Foster’s key projects, including Creek Vean (1966), an early house in Cornwall, and the world’s first terminal for space travel, Spaceport America (2014), built in the desert landscape of New Mexico. Drawings, sketches, photographs and insightful text explore projects that include furniture, houses, schools, museums, headquarters, skyscrapers, urban masterplans, vehicles, high-speed rail stations and airports. The book also features an essay by Frédéric Migayrou, curator of the major Centre Pompidou exhibition on Foster; a biography by celebrated architectural critic, Philip Jodidio; and an extensive interview with Foster himself. Foster has also contributed an anthology of six analytical texts, written across the broad span of his career.

Edited by Frédéric Migayrou

ISBN: 978-1-78884-227-3 £50.00/$65.00 www.accartbooks.com 9 781788 842273 56500

Norman Foster Inspirations

2017

Pencil on paper

29.7 × 20.8 cm (11 5/8 × 8 1/8 in)

Norman Foster Inspirations

2017

Pencil on paper

29.7 × 20.8 cm (11 5/8 × 8 1/8 in)