One of the most brilliant and controversial Italian writers of the mid20th century, Curzio Malaparte (1898–1957) was a novelist, filmmaker, war correspondent and diplomat. His long essay Maledetti Toscani (Those Cursed Tuscans) seeks to define the elements that distinguish the region and its people, and while undoubtedly mischievous (The New York Times called it ‘pretentious and bombastic’), it is frequently amusing and always acutely perceptive.

Every country has its wind; every land is distinguished by the way it breathes: and the breath that sweeps the leaves from the olive trees, swells the tops of the pines, smooths the stones of the walls and the façades of the houses, causes the hair to fly over the foreheads of the girls, and cleans the sky in the turbulent March days, is the sigh of earth itself, its profound respiration.

Also Tuscany has its way of breathing, rather different from that of Liguria, Emilia, Romagna, Umbria and Lazio, her neighbours. But to say ‘different’ is not to say all: one ought to say ‘contrary’. It breathes in the same manner as the inhabitants, as the stones, the plants, the rivers, and the sea. Four are the winds also in Tuscany – the cardinal winds, that is – and they are called the grecale (northeast), the libeccio (southwest), the scirocco (southeast) and the tramontana (north). But these aren’t the winds that gave Tuscany its character, its colour, its breadth, nor the winds that give that tone to the skin, the earth, the eyes and the leaves.

Out of Lazio the grecale packs the heavy odour of sheep and horses: you catch whiffs of warm air laden with smoke from great fires flickering at the mouths of Etruscan tombs along the wild slopes of Montalto di Castro, Tarquinia and Tuscania. You smell the rancid odour of pecorino drying in the sun on aromatic beds of herbs, of curds boiling in great kettles, of sheep hides nailed to the doors of huts, of mud cracking beneath a torrid sun. You smell the sour odour of the wild boar heaving through the thicket, of the hot blood rushing from the stuck pig in the slaughter pen, of the black Maremma bufale lumbering

The libeccio blows in from the sea. It is a sudden wind, churlish, violent, mad and thieving. It blows in from Morocco and Spain. It is a wind escaped from prison, making up for its long confinement. It plummets down hard on the waves, lifts them, gathers them, scatters them, pushes them, like frightened sheep, against white beaches, purple shoals, blackened piers. It dives like a hawk against the sails, and shivers them: tatters of sails whirl away in the gale, like flurries of doves. Its whistle, long and rabid, as sharp as a sickle, slashes the grasses of marine pastures to ribbons, sending rearing herds of foam-maned horses over the green sea nickering. The horizon splits: from the prisons of Algiers and Spain the half-nude prisoners are fleeing, screaming with joy. Through gashes in the sides of sailing ships torn apart by the tempest are thrust the drunken heads of the crew, tongues cracked and swollen with scurvy. Packs of mad dogs howl wildly on the crests and in the valleys kicked up by the furious waves. Then everything is swept up and away to assault Leghorn and Viareggio: rags at windows snap like whips, as do battened-down sails, clouds of dust swirl up from the streets, a silvery sheet of mist swirls away from rocks and shoals to invade the cities and fan out over the land. The brackish odour of salt and the creaking sound of masts and bowsprits make their way into prisons, hospitals, convents. Men, beasts, prisoners on straw mats, the ailing on the beds, friars in their cells, madmen in the madhouse, old people in the old homes, peasants in the fields and woodcutters on the slopes – all have their mouths filled with the sea. The libeccio ! The libeccio ! cry the children, pouring out of school, books under their arms. Everywhere is joyous: there is shouting, running, leaping. The whole coastline is white with foam. A beautiful wind, the libeccio – but it’s not ours.

The scirocco blows in from Elba, from the Isola del Giglio, from the marine inferno, a soft and humid wind, blowing lazily, listlessly, lounging up and down the streets, leaving behind it the odour of tobacco, wine, rotten fish and tar. ‘Smells of cheese’, say the Sicilians about the scirocco. A paunchy wind, blubbery, wrinkled, all fat and skin, with enormous hairy hands that clap across your mouth, caress your cheeks, slide along the arms, up and down the spine: and on

The Wild Winds of Tuscany through canebrakes and rushes along the drainage ditch of the reclaimed land. You feel that the heavy yellow odour of tuffaceous rock is mixing in the thin air with the fresh blue odour of ‘serene’ stone. For in the air here, at the boundary of Castro Duchy where the Maremma becomes Campagna, there is wafted up the ancient conspiracy of tuffaceous sarcophagi, travertine columns, brick aqueducts, Maremma wheatshocks, and the ‘serene’ stone and green marble of the churches and houses of Tuscany. A beautiful wind, the grecale – but it’s not ours.

Little is known of Etruscan society except what the Romans (who disapproved of their predecessors) would tell us. D H Lawrence wanted to understand more about their legacy, and travelled through the countryside of Etruria (now ‘Tuscany’) during the spring of 1927, searching the artefacts and tombs for clues. His travel essays from the time reveal a life-affirming world in sharp contrast to the shabbiness of Mussolini’s Italy, and leave no doubt as to the importance of wine as part of the Etruscan culture.

The Etruscans, as everyone knows, were the people who occupied the middle of Italy in early Roman days and whom the Romans, in their usual neighbourly fashion, wiped out entirely in order to make room for Rome with a very big R.

Now, we know nothing about the Etruscans except what we find in their tombs. There are references to them in Latin writers. But of first-hand knowledge we have nothing except what the tombs offer. So to the tombs we must go…

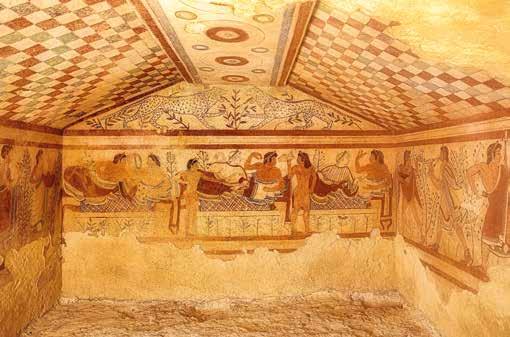

In the Tomba dei Baccanti, ‘Tomb of the Bacchants’, the colours have almost gone. But still we see, on the end wall, a strange wondering dancer out of the mists of time carrying his zither, and beyond him, beyond the little tree, a man of the dim ancient world, a man with a short beard, strong and mysteriously male, is reaching for a wild archaic maiden who throws up her hands and turns back to him her excited, subtle face. It is wonderful, the strength and mystery of old life that comes out of these faded figures. The Etruscans are still there, upon the wall.

The Tomba dei Vasi Dipinti, ‘Tomb of the Painted Vases’, has great amphorae painted on the side wall, and springing towards them is a weird dancer, the ends of his waist-cloth flying. On the end wall is a gentle little banquet scene, a bearded man softly touching the woman with him under the chin, a slave-boy standing childishly behind, and an alert dog under the couch. The kylix, or wine-bowl, that the man holds is surely the biggest on record; exaggerated, no doubt, to show the very special importance of the feast. Rather gentle and lovely

is the way he touches the woman under the chin, with a delicate caress. That again is one of the charms of the Etruscan paintings: they really have the sense of touch; the people and the creatures are all really in touch. It is one of the rarest qualities, in life as well as in art. There is plenty of pawing and laying hold, but no real touch. In pictures especially, the people may be in contact, embracing or laying hands on one another. But there is no soft flow of touch. The touch does not come from the middle of the human being. It is merely a contact of surfaces, and a juxtaposition of objects. This is what makes so many of the great masters boring, in spite of all their clever composition. Here, in this faded Etruscan painting, there is a quiet flow of touch that unites the man and the woman on the couch, the timid boy behind, the dog that lifts his nose, even the very garlands that hang from the wall.

Above the banquet, the triangle: instead of lions or leopards, we have the hippocampus, a favourite animal of the Etruscan imagination. It is a horse that ends in a long, flowing fish-tail. Here two hippocampi face one another prancing their front legs, while their fish-tails flow away into the narrow angle of the roof.

‘Tomb of the Leopards’ (480–479BC) a banquet scene is topped by two heraldic leopards. Etruscans were skilled sailors and traders and revered the animals and wines they met on their travels.

The 20th century saw Cabernet Sauvignon’s star in Tuscany rise beyond all expectation. Hugh Johnson explains how the French grape put Sangiovese on its mettle and threatened to move Chianti down to the coast.

Florence, 1904. The Marchese Piero Antinori leaves his palace in the city centre, its vast blocks of rusticated stone blackened by time and soot, to drive to Santa Cristina. The other side of the Arno, as he clatters up the road towards the monastery of the Certosa, the sun comes out from behind grey stormclouds, the bare poplars shine like bundles of bronze rods, mimosa sends wafts of honey across the road.

Antinori is putting a plan into action. The Chianti he and his friends make on their estates is absurdly rough-and-ready. It was good in the past, even exported in bottles to England under the name of Florence. It was a puzzle why French theories for improvement did not work in Tuscany. At Brolio Castle Bettino Ricasoli certainly made improvements, after he was prime minister, using a blend of red and white grapes. But on this cold soil of the Chianti hills the main grape, the Sangiovese, is just too astringent. In most years you have to alleviate its bite as best you can, and the result is not exactly exquisite.

The Marchese has a case of Château Lafite with him. He has the means, he has the land, he has a warmer climate than Bordeaux. Why can’t he make claret at Villa Antinori? The first thing is to try a blend: see what happens if he mixes his Villa Antinori with Lafite. He calls the cellar master: they blend; they taste; the cellar master makes a face – Antinori thinks it is a vast improvement. Bordeaux grapes are the way to go.

We know the outcome of this story. A hundred years later some of Tuscany’s greatest wines are Cabernets and Merlots. Sangiovese has been taken in hand and subdivided. Now it is celebrated as several good but different varieties for different regions. One of Antinori’s grandsons has created an international

wine empire based at Santa Cristina. Others have virtual Bordeaux châteaux on the coast where he bred horses. Chianti, as Tuscany’s most famous contribution to the table, symbolized by its pot-bellied fiasco in a straw jacket, has almost disappeared and has few mourners. I am one, as I recall the simplicity of the thing, and the beauty of that bottle. It looked better in a field than on a table, propped at an angle against an olive tree in the light shade where the bread and ham and fruit were spread on a sun-speckled cloth. It elevated the peasant to possess such things; his muddy wine was made sacramental. At least that is the enduring myth of a country that still sees itself as an idyll from a perfect past, though its oxen are gone, its fields have been bulldozed, and its olive presses and shrines are outnumbered by swimming pools.

As a new Bordeaux, Tuscany has done brilliantly. Antinori’s idea was perfect: lace your Chianti with Cabernet and bottle it in a Bordeaux bottle. His grandson Piero told me 20 years ago that Cabernet was the secret agent in his Villa Antinori Riserva. ‘One day,’ he said, ‘I hope we won’t need it. We’ll go back to Chianti made from only Tuscan grapes, but first we have to improve the grapes. Meanwhile, it takes only 10 percent of Cabernet to boost the flavour.’ I have watched the various stages of conversion of Tuscany’s vineyards, from haphazard old jumbles of red and white grapes using olive trees, even elm trees, as props and climbing frames, vegetables and all the colourful necessaries of a peasant life growing beneath, to today’s trim monoculture. It is hard to deny that it mirrors a total change in the wine they produce. The difference is that the wine has changed for the better.

The roots of ravishing landscape and poor wine were the same: the mezzadria, the sharecropping system in which the peasants, the contadini, gained nothing by their efforts. The Tuscany I first knew was the paradox of a rich land whose main export was its population, to America. Wine was made indifferently from black grapes and white harvested in great swags, some from trees, some from trellises like washing lines. They were thrown into a battered vat on wheels pulled by a pair of oxen and crushed with a club in the field. It was no wonder most preferred the wine in a state short of full fermentation, before it went both sour and bitter. A little sweetness and a gentle fizz made it drinkable. That was what was expected of Chianti, certainly in the trattorias of America that must have been its best customers.

I made it part of my research to investigate Italian transatlantic life at all levels on the steamship Rafaello sailing from New York to Naples. First Class

The Fortune Changer

I should like to see a snake

Get up in August out of a brake, And fasten with all his teeth and caustic

Upon that sordid villain of a rustic, Who, to load my Chianti’s haunches

With a parcel of feeble bunches, Went and tied her to one of those poles, –Sapless sticks without any souls!

Like a king,

In his conquering, Chianti wine with his red flag goes Down to my heart, and down to my toes: He makes no noise, he beats no drums; Yet pain and trouble fly as he comes. And yet a good bottle of Carmignan, He of the two is your merrier man; He brings from heav’n such a rain of joy, I envy not Jove his cups, old boy. Drink, Ariadne; the grapery Was the warmest and brownest in Tuscan Drink, and whatever they have to say,

Still to the Naiads answer nay; For mighty folly it were, and a sin, To drink Carmignan, with water in…

Bacchus in Tuscany: A Dithyrambic Poem, by Francesco Redi (1685), translated by Leigh Hunt in 1825, is 1,000 lines long. It is out of copyright and widely available to read online, in both its original and its translated forms.

CHIANTI CLASSICO FOREVER!

Carla Capalbo opens the door to Chianti Classico, one of Italy’s most beautiful and famous fine-wine regions, whose tranquil villages and vineyards have been the setting for more than a century of revolution, tumult and unsettling debates about its future.

Chianti Classico is the core of Tuscany – a heart-shaped hilly area that sits neatly below Florence and above Siena, with natural river-valley borders to both east (Valdarno and Val di Chiana) and west (Val d’Elsa). The Chianti hills acted as a natural boundary for a delineation first shaped in 1716 by the Grand Duke of Tuscany. The roads leading into this complex terrain – from Impruneta,

The tranquil vineyards of Radda were the birthplace of one of the first Super Tuscan rebels.

As Chianti Classico takes centre stage with its long-awaited regional codification, Stephen Hobley wonders what’s happening with the ‘other’ Chiantis, the seven subzones that surround the DOCG’s heartland... He finds dynamic vineyard regions newly reborn, all with heightened respect for their territories.

The Consorzio Chianti website tells us that ‘Chianti’ is one of the 10 first words of Italian for new speakers of the language. Apparently, it’s up there with mamma, pizza, ciao and amore. Certainly, its recommendation as an accompaniment to a tasty dish of liver in The Silence of the Lambs (1991) was a resounding endorsement. Even more interesting, the wine specified in the movie was specially renamed: the original book had it as a ‘big Amarone’, but for an Anglophone audience a better-known name was required.

Chianti, then, is super famous. But what type of Chianti are we talking about? When I went to Tuscany first in the 1980s, the choice was either ‘Chianti Gallo Nero’, the Black Rooster of Chianti Classico, which was the ‘serious’ wine capable of comparison with the major reds from France, or ‘Chianti Putto’, the young, easy-drinking wine beloved of the trattorias, coming from the ‘lesser’ regions outside Chianti Classico and used to wash down crostini with chickenliver pâté, often made using the softening second-fermentation governo all’uso toscano technique and served from the iconic wicker-framed fiasco.

Chianti Putto has now disappeared, and Chianti Classico has gone its own way, divorced from the DOCG Chianti denomination in 1996, and now doing very well, thank you, with recent innovations propelling the level of wine produced to ever higher levels of quality. The initially controversial Gran Selezione concept, for example, has been used to identify superior cuvées and, by implication, superior vineyard sites. It’s now been followed by the creation of official UGAs: 11 different Unità Geografiche Aggiuntive (Additional Geographical Units) that divide up the denomination of Chianti Classico into

coherent individual growing areas, large and small, in a move that took years to put into practice.

What does Chianti look like outside Classico? First of all, it’s important to note that the category is Tuscany’s biggest. Statistics for the provision of the official contrassegni bottle stickers, as reported by Associazione Vini Toscani DOP e IGP for the month of January 2024, show that Chianti currently represents 37.30 percent of Tuscan wine on sale. Just for comparison, the next biggest categories are IGT Toscana (29.95 percent), Chianti Classico (14.07 percent) and Brunello di Montalcino (5.01 percent).

The Chianti subzone denominations beloved of the textbooks date back to the ministerial decree of 1932, promulgated by a regime that realized that Chianti was synonymous with ‘Italian wine’ on the export market and that an increase in availability might help fill the coffers. The result was that an expanded potential production area for Chianti was recognized throughout most of central Tuscany, stretching from Pisa in the west (Chianti Colline Pisane) to Arezzo in the east (Chianti Colli Aretini), passing through the provinces of Pistoia and Firenze (Chianti Montalbano, Chianti Rùfina and Chianti Colli Fiorentini) and down through to Siena (Chianti Colli Senesi). Much later, in 1997, Chianti Montespertoli, southwest of Florence, was added to the list as a uniquely wellqualified viticultural area.

The subzones account for only about eight percent of the total Chianti DOP1 production in terms of volume, around 6.5 million bottles per year. These are mostly the wines I will talk about here, but by far the lion’s share of Chianti DOP is made in the same sub-zones and labelled as generic Chianti, Chianti Superiore and Chianti Riserva, accounting cumulatively for 87.5 million (2021), 73.6 million (2022) and 68.9 million (2023) bottles in the last three years. All Chianti is now DOCG (Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita), the highest denomination, granted in 1984.

In practice, the official list of seven Chianti subzones outside Classico is increasingly notional. You’ll be hard pressed to find any bottles labelled Chianti Colline Pisane (I haven’t found even one) or Chianti Colli Aretini (pace Mannucci Droandi, who make an excellent example), which doesn’t mean that

1 DOP – Denominazione di Origine Protetta, protected designation of origin.

Evocative tasting notes quickly convey the seductive power of the Super Tuscans and why it is that the critics (and Italophiles with deep pockets) fell instantly in love with them. Jane Anson’s show what all the fuss is about.

Sassicaia 1985 – Tenuta San Guido, Bolgheri

So finely spun, with pillowed tannins, perfect weighting and freshness through the palate, fires up your senses with rosemary, white truffle, mocha, underbrush, olive tapenade, redcurrant and crushed raspberry, utterly moreish. No hint of it going anywhere after an hour in the glass, even at almost 40 years old. This was a low-yield vintage after a very cold winter, where 80 percent of the olive trees in Tuscany were destroyed, which no doubt contributes to this concentration and persistence. And if you want to know if setting makes a difference to enjoyment, I first tasted this almost 10 years ago during an estate vertical in a fresco-ceilinged Roman palace overlooking the fountains of Piazza Navona. This time I was at home with a bowl of (excellent) pasta. Both times a stone cold 100 points.

Ornellaia 1998 – Frescobaldi, Bolgheri Superiore

Fully in the sweet spot right now, where it shows character and finesse, with muscular damson and red cherry fruits, grilled pomegranate, liquorice and fennel

Ornellaia, created by Lodovico Antinori and winemaker Tibor Gál, from vineyards planted in 1981. Its first vintage was 1985.

notes as it opens, layering on charred sandalwood, cigar box and truffle. Holds up well in the glass, uncovering further nuances over a good hour or more, and this is just a spectacular wine, ready to go. The 1998 vintage saw a sunny summer with almost no rainfall, harvest from first week of September until early October, lasting almost exactly one month. 50 percent new oak barrels for ageing. Winemaker: Andrea Giovannini. (99 points)

Axel Heinz turning out yet again a wine that is generous and moreish but that goes deeper, offering layers of coffee, smoked herbs, rosemary, saffron, gentle waves of powerful brambled fruits. Mouthwatering, with tension and precision. Finely spun tannins that are elastic in embracing and taming the exuberant fruits yet chewy enough on the finish to show there is plenty of ageing ability ahead. Makes a big impression and yet has that Italian ability to be gulpable at the same time. A more elegant, moreish version of Merlot than you get in the biggest Pomerols, but every bit as beautiful. (100 points)

So much promise on the nose, your mouth starts watering in anticipation even before the vivid fruit hits on the opening beats. This holds the line throughout, delivering classic Sangiovese character of raspberry, fresh cherries and cut herbs, with concentrated liquorice, tobacco, tar and leather. Sculpted and precise, and that perfect Italian signature where you just want to grab a bottle and a plate of food to go alongside. So easy to love, and more proof of how enjoyable the 2019 vintage is in this part of the world. 70 percent new oak in barrel and cask format, plus four months in concrete tanks before release. Winemaker: Gionata Pulignani. (97 points)

I Sodi di San Niccolò 2020 – Castellare di Castellina, IGT Toscana

Aromatic white pepper, dried roses, sage and bay leaf spices, you are taken right into the heart of Tuscany. Elegant, structured, raspberry, pomegranate and redcurrant fruits, savoury and mouthwateringly dry, rippled with aromatics of black tea, tobacco and underbrush. 66 percent new oak, 10 months in bottle after barrel ageing. Winemaker: Alessandro Cellai. Such a fan of this wine, built to be shared. (96 points)

Solaia Toscana 2020 – Marchesi Antinori, IGT Toscana

A great vintage of the iconic Solaia, full of cloves, sage, graphite, grilled dried herbs, underbrush and roasted cherry pit. There’s fruit too, bilberry and cassis, juicy and mouthwatering, both understated and exuberant, ensuring a Tuscan fingerprint despite its majority Cabernet construction. Has grip and length, and effortless charm, reflecting an excellent vintage with low yields after a hot, dry summer. Antinori family showing once again why this wine, that comes from 20 hectares on the sunniest slopes of the Tignanello estate, set at 350–400m altitude, is so hard to resist. Winemaking director: Renzo Cotarella. (98 points)

2021

Just love this wine; the lyricism and the generosity of it, and its always-vivid depiction of fruits and stones. So juicy, so drawn out, works with the vintage, leans into its low yields, with greengages, raspberry, plum, gentle spices, lemongrass, minerality studded with mandarin peel and sage. Translucent and yet full of flavour, it begs you to draw up a chair, gather friends, and enjoy. What a brilliant wine and a brilliant winemaker in Bibi Graetz. From a 58-hectare estate, Colore comes from the oldest vineyards of Sangiovese, vines ranging up to 135 years. (100 points)

Tasting notes all available at janeanson.com; reproduced here with kind permission of the author.

Have we reached the peak of what international varieties can do for Italian wine? asks Jane Anson. And is the time now ripe for Italy and its major producers to start celebrating their own array of lesser-known indigenous grape varieties?

Rolling Stone was put up for sale in 2017, almost 50 years to the day since its first issue was produced out of a loft in San Francisco with a loan of US$7,500.

I started looking up early copies online when I read of the sale, finding a PDF of the first ever issue from November 1967. It looked more like a newspaper than a magazine, with an arresting front-page image of John Lennon posing in a World War II service uniform for Richard Lester’s film How I Won the War (1967).

For wine lovers, revolution in the 1960s became so heady that it escaped all the way from California to the quiet slopes of Chianti Classico, and to the most unlikely of counterculture heros – Italian nobleman Marchese Mario Incisa della Rocchetta. His Bordeaux-inspired Cabernet Sauvignon-led Sassicaia made its official launch out of French oak barrels in 1968, bottled as a table wine because it fell outside of the traditional rules. In doing so, it reset the conversation about Italian wines, establishing a small band of rebel winemakers working outside the prevailing traditions, breaking the rules and setting the world of wine alight.

You don’t need me to list the many brilliant wines inspired by Incisa della Rocchetta’s leap in the dark, but the Rolling Stone sale seemed to rather neatly round off the era, and usher in a question that has been increasingly loud in recent years – namely, whether we have reached Peak Super Tuscan, and if today’s true counterculture wines in Italy are those that rely instead on tradition rather than innovation?

Someone who should understand the issue more than most is Dr Paolo Panerai, owner of Rocca di Frassinello in Maremma and Castellare di Castellina in Chianti Classico. A journalist since 1970, he studied law and agricultural

Viticultural consultant, wine critic and author Monty Waldin charts the rise of modern Montalcino, his home for the last 20 years, from medieval backwater to celebrated wine destination. He tells the story of the Biondi Santi family, whose wines started the Brunello legend, carrying it to the modern day and to the eyes of the world.

Montalcino is famed not just for its wines but for its beauty. It is a hill town and comune in the centre of what was once Etruria, the land of the Etruscans. Its pivotal defensive position, atop a cluster of hills that command the surrounding countryside with views in all directions, meant its sustained its power throughout the Middle Ages. However, Montalcino is not named for the hills but for the strong, evergreen holm oaks that thrive here, with acorns that mature in a single summer – Mons ilcinus meaning ‘mountain of the holm oak’.

The territory of Montalcino ranges over an area of 310 square kilometres, of which 29 percent is plains, 70 percent hills and the final one percent mountain. It is only 40 kilometres from the Tyrrhenian Sea, so its vineyards retain the advantage of cooling breezes from the coast. Nor is potable water lacking, thanks to the surrounding freshwater courses – the rivers Arbia, Orcia, Asso and Ombrone, the latter being the largest and most important. In pride of place is Mount Amiata (1,738m), a volcanic mass that dominates Montalcino and guarantees its protection from the searing hot scirocco winds blistering in from the south.

Montalcino lies 42 kilometres south of the city of Siena, home to Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena, the oldest bank in the world, traceable back to 1472. Montalcino locals point out that the financial solidity this implies is not guaranteed hereabouts, saying that it is only when a wine grower goes to the ‘Great Vineyard in the Sky’ that he or she can relax, and hope to have left enough in the pot for the next generation to carry on.

Today, Montalcino’s out-of-the-way location is considered a benefit – just as it was in medieval times when, despite the vying attentions of Siena and Florence,

it was the last of Italy’s independent towns to succumb to Medici power. Tourists seeking Brunello and beautiful landscapes regularly make their way to the area, especially in the summertime, and the town and surrounding area prosper while retaining their original charm. It seems incredible that Montalcino might ever have been dirt poor, but, cut off from the Autostrada A1, the main Milan to Rome motorway completed in 1964, it was. The ‘ilcinesi ’ began to look for opportunities away from home, and one-third of the population left, including the bishop; the village’s only hospital was forced to close. Many of those who ignored the naysayers and stayed were winemakers.

No Montalcino wine is more famous than the dark, crimson-coloured Brunello, created in the mid-19th century by Clemente Santi. Clemente was born in Montalcino in the year of the French Revolution, 1789, to Luigi Santi, a pharmacist, and Petronilla Canali, a knowledgeable historian. Petronilla was the daughter of Tullio Canali, known for writing a historia of Montalcino in the mid-18th century.

Clemente Santi studied at the University of Pisa, an institution renowned for its revolutionary studies in the agricultural sciences; and although his degree course was in pharmacy he soon realized that agronomy was his true passion. In

The hill of Montosoli, famously home to the first single-vineyard cru of Brunello di Montalcino, released by the Altesino family in the 1970s.

The iconic Italian poet, philosopher, writer and political thinker (often referred to as Dante), was author of The Divine Comedy (La Divina Commedia), widely considered the greatest literary work not only of the Italian language but of all medieval European literature. Written in the standard Tuscan dialect, rather than Latin, using vivid vocabulary and inventive analysis of contemporary problems, it is an allegorical journey through hell, purgatory and paradise towards the ultimate end-point, salvation. Dante was born in Florence.

The greatest writer of spoken (vernacular) Italian of the medieval period, credited with introducing the Classics, ancient mythology and geography, to Renaissance Italy via both poetry and prose in realistic dialogue rather than the formulaic plots of his contemporaries. His popularity extended beyond Italy and his writing was known to have influenced Geoffrey Chaucer and Miguel de Cervantes. Boccaccio helped lay the foundations of humanism in Italy. He was born in Certaldo, southwest of Florence.

Brunelleschi began his career as a sculptor with a talent for capturing maximum dramatic impact, but on losing out to his rival in an important commission he turned to architecture instead. A talent for solving complex engineering problems soon emerged. Brunelleschi is famed for his rediscovery of the Roman and Greek principals of linear perspective, and subsequently for successfully circumventing the problems of vaulting the new dome of Florence’s Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore (the Duomo) by inventing the machinery necessary to suspend it without external buttresses. He was born in Florence.

1475–1564)

Sculptor, painter, architect and poet, Michelangelo was lauded as the greatest living artist within his own lifetime. His work embraced and reflected the dramatic political, scientific and religious changes of the Renaissance, particularly his best-known works The Creation of Adam (part of the fresco adorning the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel), David (the 5.17-metre statue at Florence’s Accademia Gallery), and The Last Judgement (covering the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel). He was born in Caprese to a family of minor nobility and his initial studies in sculpture were sponsored by the Florentine ruler Lorenzo the Magnificent of the powerful Medici family.

Galilei (astronomer, 1564–1642)

Considered the father of modern science, Galileo contributed widely to the studies of astronomy, physics, mathematics, cosmology and philosophy. His work on improving the telescope and the thermoscope (a forerunner of the thermometer), in inventing military compasses and in building an early microscope, provided a basis for Renaissance thinking that saw him at odds with the Catholic Church – he was eventually placed under house arrest for heliocentric beliefs that contradicted biblical creationism. Galileo was born in Pisa.

1593–c1656)

Gentileschi painted autbiographically, portraying the horrors of her own life – rape, repression, injustice – in brutal biblical paintings that saw her gaining early recognition and acceptance as a fine artist (in what was very much a man’s world). Initially a follower of Caravaggio, she quickly developed her own style and became the first female member

The Anglo-Welsh travel writer and diarist Hester Lynch Piozzi (1741–1821) was a popular socialite and mother of 12 children. Following the death of her first husband, the brewer Henry Thrale, she married Italian musician Gabriele Piozzi, with whom she embarked on a journey to Italy from 1784 to 1787. The resulting Observations and Reflections Made in the Course of a Journey Through France, Italy and Germany received approbation and opprobrium (sometimes quite harsh) in equal measure. Her friend and fellow author Frances Burney said of Hester: ‘She is a most dear creature, but never restrains her tongue in any thing.’

Sienna, 20th October 1786

We arrived here last night, having driven through the sweetest country in the world; and here are a few timber trees at last, such as I have not seen for a long time, the Tuscan spirit of mutilation being so great, that every thing till now has been pollarded that would have passed twenty feet in height: this is done to support the vines, and not suffer their rambling produce to run out of the way, and escape the gripe of the gatherers. I have eaten too many of these delicious grapes however, and it is now my turn to be sick – No wonder, I know few who would resist a like temptation, especially as the inn afforded but a sorry dinner, whilst every hedge provided so noble a dessert. Paffera pur la malattia [the disorder will die away though] as these soft-mouthed people tell me; the sooner perhaps, as we are not here annoyed by insects, which poison the pleasure of other places in Italy; here are only lizards, lovely creatures! who being of a beautiful light green colour upon the back and legs, reside in whole families at the foot of every tree, and turn their scarlet bosoms to the sun, as if to display the glories of colouring which his beams alone can bestow.

The pleasing tales told of this pretty animal’s amical disposition towards man are strictly true, I hear; and it is no longer ago than yesterday I was told an

odd anecdote of a young farmer, who, carrying a basket of figs to his mistress, lay down in the field as he crossed it, quite overcome with the weather, and fell fast asleep. A serpent, attracted by the scent, twined round the basket, and would have bit the fellow as well as robbed him, had not a friendly lizard waked, and given him warning of the danger.

Swift says, that in the course of life he meets many asses, but they have not lucky names. I have met many vipers, and so few lizards, it is surprising! but they will not live in London. …

This town is neat and cleanly, and comfortable and airy. The prospect from the public walks wants no beauty but water; and here is a suppressed convent on the neighbouring hill, where we half-longed to build a pretty cottage, as the ground is now to be disposed of vastly cheap; and half one’s work is already done in the apartments once occupied by friars. With half a word’s persuasion I should fix for life here. The air is so pure, the language so pleasing, the place so inviting; – but we drive on.

Mrs Hester Lynch Piozzi (1785, oil on canvas – unknown artist). Her writing was polarizing but full of observation and fresh insights into the countryside through which she travelled.

David Gleave has imported wines from Italy for 38 years. For full disclosure, the producers he has represented, who are included in the parts of this book, are Isole e Olena, Fontodi, Felsina Berardenga, San Giusto a Rentennano, Selvapiana and Capezzana. We would like to wish David our warmest thanks for his help and guidance in producing this book. It has been a great pleasure to work with him and On Tuscany is all the richer for the knowledge he brings to its pages.

We are extremely grateful for the generous support provided by the Daou brothers’ project, Tenuta Giorgio e Daniele. Daniel and Georges Daou, legendary and award-winning winemakers in Paso Robles, California, have extended their vision to a 173-acre estate in the Val d’Orcia region in southern Tuscany where they will soon be producing world-class wine. They will be a welcome addition to this dynamic region.

Front cover Adobe Stock; p5 (top left) Dan74/Adobe Stock; p5 (top right) ledmark31/Adobe Stock; p5 (bottom left) Andrea Bonfanti/Wirestock/ Adobe Stock; p5 (bottom right) wjarek/Adobe Stock; pp9, 13, 16, 20, 23, 29, 38, 42, 46, 51, 56, 66, 69 (top), 78, 82, 92, 102, 114, 121, 130 (top), 133, 137, 144, 152, 158, 169, 176, 194, 200, 207 (top), 217, 220, 226, 232, 234, 236, 239, 242, 251, 259 Ezio Gutzemberg/Adobe Stock; pp14-15 stevanzz/ Adobe Stock; p21 David Pineda Svenske/Shutterstock; p25 Massimo Santi/Adobe Stock; p33 Cosmographics; p34 Marco Taliani de Marchio/Shutterstock; p36-37 barmalini/Adobe Stock; p39 BGStock72/ Adobe Stock; p45 Tenuta San Guido; p53 marcoemilio/Adobe Stock; p54 ermess/Adobe Stock; p57 marcovarro/ Shutterstock; p60 MNStudio/Shutterstock; p63 Hawkee/Shutterstock; p64-65 Massimo Santi/Adobe Stock; p69 (bottom) StevanZZ/Shutterstock; p80 Andrea/Adobe Stock; p85 Cosmographics; p95 Mick Rock/Cephas; p104 Mick Rock/Cephas; p112-113 StevanZZ/Shutterstock; p116 Wikimedia Creative Commons; p130 (bottom) Mick Rock/Cephas; p132 Ranimiro/Adobe Stock; p142-143 daliu/Adobe Stock; p145 Monty Waldin; p148 Luis Marden; p151 Biondi-Santi; p160 Alessandra Renieri; p170 leoks/Shutterstock; p175 Gabriele Gorelli; p177 stevanzz/Adobe Stock; p180 Clay McLachlan/Cephas; pp184-185 NickolayV/Shutterstock; pp186-187, 188-189, 190-191 PhotoLondonUK/Shutterstock; p186 (top left) spatuletail/Shutterstock; p186 (centre left) Morphart Creation/Shutterstock; p186 (bottom left) Wikimedia Creative Commons; p187 (top left) Everett Collection/Shutterstock; p187 (centre left) Everett Collection/Shutterstock; p187 (bottom left) Wikimedia Creative Commons; p188 (top left) Public Domain, p188 (bottom left) Public Domain; p189 (top left) Wikimedia Creative Commons; p189 (centre left) Everett Collection/Shutterstock; 190 (top left) Morphart Creation/Shutterstock; p190 (centre left) Public Domain; p190 (bottom left) Public Domain; p191 (centre left) Morphart Creation/Shutterstock; p191 (bottom left) Everett Collection/Shutterstock; pp192-193 wjarek/Adobe Stock; p195 Herbert Lehmann/Cephas; p203 © Frescobaldi; p207 (bottom) Clay McLachlan/claymclachlan. com ; p211 Clay McLachlan/Cephas; p212 Monty Walden/Cephas; p214 Herbert Lehmann/Cephas; p218 Bibi Graetz; p227 Daniel and George Daou; p229 Daniel and George Daou; p240-241 Michael Evans/ Adobe Stock; p233 Active Museum/Active Art/Alamy Stock Photo; p235 Ekaterina Belova/Adobe Stock; p241 Wikimedia Creative Commons; p243 Elizabeth Berger; p246 Elizabeth Berger; p255 Marco Taliani de Marchio/ Shutterstock; p261 (top) Alessandro Cristiano/Shutterstock; p261 (bottom) Michael J Magee/Adobe Stock

The publishers have made every effort to trace the copyright holders of the text and images reproduced in this book. If, however, you believe that any work has been incorrectly credited or used without permission, please contact us immediately and we will endeavour to rectify the situation.