Tom Wesselmann pop Forever

Wesselmann and Pop Forever: Dream and Reality in a Theoretically Real World

Dieter Buchhart

Tom Wesselmann in his first studio, at 175 Bleecker Street, New York, in 1962, with Great American Nude #21 (1962), in progress. Photograph by Jerry Goodman

1. Byung-Chul Han, The Expulsion of the Other: Society, Perception, and Communication Today, trans. Wieland Hoban (London: Polity, 2018), p. 42.

2. Erich Kasten, Heinz Oberhummer, and Mathias Mertens, “Woher wissen wir, was Realität ist?,” Zeit Wissen, no. 3 (April 15, 2011): https://www.zeit.de/zeitwissen/2011/03/Will-wissen.

3. Han, p. 37.

4. Ibid., The Expulsion of the Other, pp. 37, 42.

5. Ibid.

6. Lucio Fontana, “Television Manifesto of the Spatial Movement,” Milan, May 17, 1952, in The Italian Metamorphosis, 1943–1968, ed. Germano Celant (New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 1994), p. 717.

The digital order causes an increasing disembodiment of the world; today, there is less and less communication between bodies. It also does away with counter-bodies by robbing things of their material heaviness, their mass, their own weight, their own life, their own time, and makes them available at all times.

—Byung-Chul Han1

Philosophers, natural scientists, and ideologues differ on the issue of what reality is. The question becomes even more complex due to the recent computer-generated expansion of our perception of reality and with virtual reality. To put it in drastic terms, is “reality only an interpretation of the brain” or “what takes place beyond human thought”?2 Does “hypercommunication” in Byung-Chul Han’s sense destroy “both the you and closeness, ”3 and does the digital order lead to a “an increasing disembodiment of the world”?4 Did the object as a “counter-body”5 run its course in art, as Lucio Fontana argued in 1952 with television, space travel, and satellite communication in mind: “It is true that art is eternal, yet it has always been bound to matter; we, on the other hand, want to release it from matter, so that,

through space, it may last a millennium, even in a one-minute broadcast.”6 Today in the age of transhumanism or posthumanism,7 in the age of social media, virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and NFTs (Non-fungible tokens), art has long been divorced from matter as artistic material, but nevertheless continues to be located within it. But what is the future of art: experience, communication, spectacle in the form of VR, AR, NFTs, and an “omniscient, omnipotent, divine AI,”8 or the manifestation of the artistic idea in material as a reflection of reality? Since the Pop Art of the 1950s and 1960s, the images that have been released into the world have multiplied seemingly infinitely. Everything is reproducible and is reproduced in an age in which the “technological reproducibility”9 of an image, of an artwork, is no longer an issue, but the very foundation of our society and communication structures. This underscores the importance of looking at Pop Art, the “New Realism” of the past, today and in the future: Is Pop Art forever?10

Tom Wesselmann, as a key figure of Pop Art and the intersection of art and everyday reality, brings these issues into focus. Like all artists gathered under the term Pop Art, Wesselmann

Tom Wesselmann: From “Superreality” to Participation Anna Karina Hofbauer

1. Jean-Paul Sartre, What Is Literature?, trans. Bernard Frechtman (New York: Philosophical Library, 1949), p. 43.

2. Slim Stealingworth, Tom Wesselmann (New York: Abbeville Press, 1980), p. 36.

3. Tom Wesselmann in an interview with Judith Stein at his studio in New York, May 24, 2002.

It is the conjoint effort of author and reader which brings upon the scene that concrete and imaginary object which is the work of the mind. There is no art except for and by others.

—Jean-Paul Sartre1

The telephone rings; it rings six times every six minutes. In Tom Wesselmann’s Great American Nude #44 (1963; pp. 162–163), the eye of the beholder focuses on the red telephone mounted on the center of the wall. What would happen if someone picked up the receiver? Would anybody be at the other end of the line? And is picking up the receiver, touching the telephone at all, even allowed? The next year, Yoko One exhibited her Telephone Piece with the request: “Please answer the telephone when it rings” (FIG. 2). In the exhibition space, there was a white telephone affixed to the wall that could only receive incoming calls. Whenever it rang, the visitors could pick up the phone and speak with Yoko Ono. Wesselmann, in contrast, could not see the point of the Fluxus view of the fundamentally symbiotic approach to a dualistic understanding of the artist and the work. The ringing of the red telephone is programmed, six rings every six minutes, adding an additional dimension to the work, lending it a touch of the uncertain,

and is able to make beholders ask briefly about the why and the how. In Wesselmann’s autobiography, published under the pseudonym Slim Stealingworth in 1980, he explains that picking up the telephone does not come into question, and that “Wesselmann’s works were not meant to be participatory.”2 All the same, the telephone and its ringing had a positive effect: “Somehow the whole painting would burst into life … the phone just sort of set off something, that was interesting.”3 The sound backdrop adds the ringing of a telephone to the assemblage, thus manifesting the real as an everyday situation by way of auditive perception and interpretation in the brain. With its physical presence, an actual radiator, silver-colored, which seems deceptively to be anchored in the floor, takes a further step toward the mutual incorporation and linkage of work and receiver, even if according to Wesselmann this was not his intention. The work moves beyond the frame set by the artist, leaving the art space that was intended for it and approaching the visitors. Conversely, the visitors approaching the assemblage are virtually drawn by the ringing of the telephone. Here, cognition and an acknowledgment of the body, and thus the human being, form a unity together with the space in the sense of the philosophy of

Tom Wesselmann with Still Life #29, 1963. Photograph by Jerry Goodmann

The Estate of Tom Wesselmann

Between a Sexual and an Aesthetic Revolution: Tom Wesselmann and the Art of Subversion

Brenda Schmahmann

any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed here are her own, and the NRF accepts no liability in this regard.

Tom Wesselmann’s works are intricately connected with two chronologically overlapping revolutions. In this essay, I reveal how the works might be understood in the light of both these groundbreaking phenomena, suggesting that—in terms of their content as well as form— Wesselmann’s works broke with tradition and positioned themselves on the side of a social, cultural, and political avant-garde.

Many of the works in this exhibition were made in the 1960s and early 1970s—the years associated with the sexual revolution. It was a revolution that, besides involving a general liberalization in attitudes toward sexuality, included a shift away from an understanding that female desire—if recognized to exist at all—should confine itself to expression within marriage.

An important factor in the sexual revolution was the contraceptive pill, first released in 1960. While groundbreaking in freeing women from

fear of unwanted pregnancies, it took some time until it was readily available. The year 1965 saw the United States Supreme Court eradicating all state laws that prohibited contraceptive use within marriage and, by 1972, birth control was also legal for the unmarried.

These years also saw issues of sexuality serving as a focus around which left-wing movements were organized. The beliefs of Wilhelm Reich, a second-generation Freudian who died in 1957, and who combined ideas about sexual liberation with socialist concepts, were a particularly strong influence on the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s. Viewing conventional morality as a disease and linked to capitalism as well as fascism, Reich envisaged a utopia in which a “natural family” would freely express itself, advocating the abolition of laws against abortion and homosexuality, free contraception, the ending of laws preventing sex education, the right of unmarried women to have

Brenda Schmahmann holds the SARChI Chair in South African Art and Visual Culture at the University of Johannesburg. Her research is made possible by funding from the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa. Please note, however, that

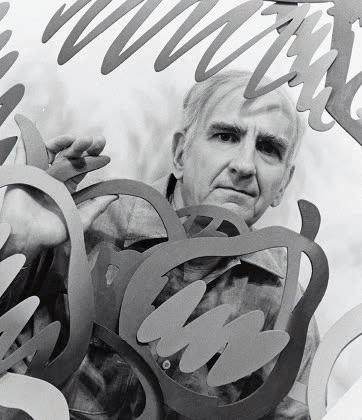

Tom Wesselmann in his studio, 1987.

Photo Nick Rozsa

The Estate of Tom Wesselmann

“The spontaneity, the false lines, etc.”: Wesselmann and Drawing

Isabelle Dervaux

Wesselmann

The author would like to thank Jeffrey Sturges, Director of Exhibitions at the Estate of Tom Wesselmann for showing her a large number of drawings and sharing his knowledge of Wesselmann’s practice.

1. In Tom Wesselmann Draws (exh. cat. New York: Haunch of Venison, 2009), p. 7. The title comes from p. 9 of the same source.

I have always used drawings as a necessary part of my paintings and my paintings are almost always an outgrowth of drawing.

Tom Wesselmann1

Pop Art is primarily associated with painting: large, brightly colored depictions of consumer goods rendered in a cool, mechanical-looking style. Yet most of the artists affiliated with the movement were also avid drawers. Many in fact began their careers in the field of commercial drawing. Andy Warhol was a fashion illustrator; Ed Ruscha, a graphic designer; Roy Lichtenstein, an engineering draftsman; and Tom Wesselmann and Wayne Thiebaud wanted to be cartoonists. Throughout their careers, these artists produced a large number of drawings, either as finished works or as studies for works in other media. It is often in their production on paper that their attachment to traditional forms of expression and the art of the past is most palpable. Even as they introduced radical innovations in their paintings and sculptures, Pop artists remained attached in their drawings to handmade marks and gestures, betraying their admiration not only for earlier modern masters such as Henri Matisse

and Pablo Picasso, but also for the Abstract Expressionists who dominated the avant-garde of their time and from whom they were trying to distinguish themselves. Such a conflicting position was at the core of Wesselmann’s practice, which relied heavily on drawing.

Wesselmann’s interest in an artistic career did not develop until the age of twenty-one, when he was drafted into the United States Army during the Korean War. As a relief to the grimness and boredom of the situation, he turned to humor and started drawing gag cartoons. It was with the goal of becoming a cartoonist that he enrolled at the Art Academy of Cincinnati in 1954 and, two years later, moved to New York to continue his studies at the Cooper Union. Stimulated by the New York art scene, however, especially the discovery of Abstract Expressionist painting, he gave up cartooning and embarked on the production of small, mixed-technique collages. Looking for a path away from the prevalent abstraction, he resolved to be a figurative artist and sought to improve his drawing skills by turning to the most academic form of training: drawing from the nude model. His early sketches, such as Nude Drawing: Judy (FIG. 1), are characterized by their speed of execution, the looseness of

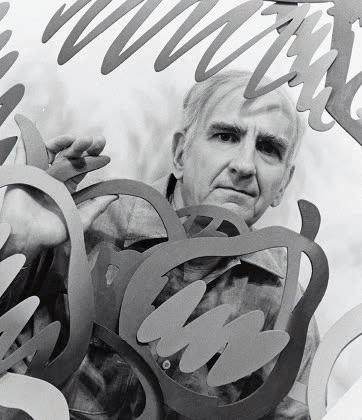

Tom

in his studio, 1992. Photo Jim Strong The Estate of Tom Wesselmann

Kurt Schwitters (1887–1948, Germany)

Ohne Titel (875 G), 1921–1924

Collage, gouache, and paper on paper

15.9 × 12.6 cm

Private collection, courtesy Galerie 1900-2000, Paris

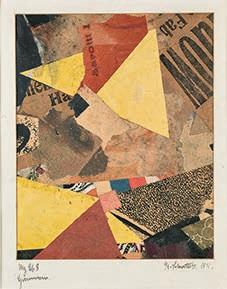

Kurt Schwitters (1887–1948, Germany)

Mz 268 Hannover, 1921

Collage and paper on paper

18 × 14.5 cm

Private collection, courtesy Galerie 1900-2000, Paris

Kurt Schwitters (1887–1948, Germany)

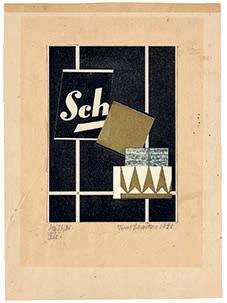

Mz 26,45 Sch, 1925–1926

Collage on paper

14.5 × 10.6 cm

Nahmad Collection

Kurt Schwitters (1887–1948, Germany)

Mz 245. Mal Kah, 1921

Collage and paper on paper

12.5 × 9.8 cm

Private collection, courtesy Galerie 1900-2000, Paris

Kurt Schwitters (1887–1948, Germany) Mz 307. Erster Platz. / Mz 307 Jettchen, 1921 Collage and paper on paper

20.5 × 16.5 cm

Private collection, courtesy Galerie 1900-2000, Paris

THE STAR-SPANGLED BANNER

Jasper Johns (born 1930, United States) Flag, 1958 Encaustic and collage on canvas

Still Life #29, 1963

Oil and printed paper

collage on canvas

Courtesy Lévy Gorvy Dayan

Still Life #33, 1963

Oil and collage on canvas, three sections

Mugrabi Collection

Seascape #1, 1965

Acrylic on panel

167.6 × 122 cm

Fabien de Cugnac private collection, Brussels

Seascape #25, 1968 Oil on linen

168 × 183.5 cm

Private collection, Europe, courtesy Sotheby’s

MOUTHS & SMOKERS

Mouth #14 (Marilyn), 1967 Oil on shaped canvas

152.4 × 274.3 cm Mugrabi Collection

©

photo credits

Cover Tom Wesselmann

Mouth #14 (Marilyn), 1967

Oil on shaped canvas

152.4 × 274.3 cm

Mugrabi Collection

@ Éditions Gallimard, Paris, 2024 www.gallimard.fr

@ Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, 2024 www.fondationlouisvuitton.fr

This catalogue’s paper is made from natural, renewable, recyclable fibers, produced from sustainably managed forests.

The catalogue is set in Syncro and Raw Paper (interior): Magno Volume 150 g

Photoengraving: Hyphen

Printed in August 2024 by Printer Trento for Maestro

Printed in Italy

Legal deposit: October 2024

ISBN: 978-2-07-307598-7

637 126